BEAUTYPAYS

DANIELS.HAMERMESH

BEAUTY

PAYS

WhyAttractivePeople

AreMoreSuccessful

Copyright©2011byDanielS.Hamermesh

Requestsforpermissiontoreproducematerial

fromthisworkshouldbesenttoPermissions,

PrincetonUniversityPress

PublishedbyPrincetonUniversityPress,41

WilliamStreet,Princeton,NewJersey08540

IntheUnitedKingdom:PrincetonUniversity

Press,6OxfordStreet,Woodstock,Oxfordshire

OX201TW

press.princeton.edu

AllRightsReservedLibraryofCongressCataloging-in-Publication

Data

Hamermesh,DanielS.

Beautypays:whyattractivepeoplearemore

successful/DanielS.Hamermesh.

p.cm.

Includesbibliographicalreferencesandindex.

ISBN978-0-691-14046-9(hardcover)1.Successinbusiness.2.Success.3.Beauty,

Personal.I.Title.

HF5386.H2432010

650.1—dc22

2011013548

BritishLibraryCataloging-in-PublicationData

isavailable

ThisbookhasbeencomposedinBauerBodoni

andGaramondPremierPro

Printedonacid-freepaper.∞

PrintedintheUnitedStatesofAmerica

10987654321

CONTENTS

Preface

PARTIBackgroundtoBeauty

CHAPTERITheEconomicsofBeauty

CHAPTERIIIntheEyeoftheBeholder

DefinitionsofBeauty

WhyDoBeautyStandardsMatter?

HowDoWeMeasureHumanBeauty?

DoObserversAgreeonBeauty?

DoesBeautyDifferbyGender,Race,orAge?WhatMakesYouBeautiful?

CanWeBecomeMoreBeautiful?

TheStageIsSet

PARTIIBeautyontheJob:WhatandWhy

CHAPTERIIIBeautyandtheWorker

TheCentralQuestions

HowCanBeautyAffectEarnings?

HowMuchMoreDoGood-LookingPeopleMake?

IsBeautytheRealCause?

WhyAreBeautyEffectsSmallerAmongWomen?

DoBeautyEffectsDifferbyRace?

DoBeautyEffectsDifferbyAge?

CompensatingtheBeauty-DamagedWorker?

LooksMatterforWorkers

CHAPTERIVBeautyinSpecificOccupations

BeautyandChoosinganOccupation

HowBigAreBeautyEffectsWhereBeautyMightMatter?

HowBigAreBeautyEffectsWhereBeautyMightNotMatter?

SortingbyBeauty

CHAPTERVBeautyandtheEmployer

ThePuzzles

DoGood-LookingEmployeesRaiseSales?

HowDoesBeautyAffectProfits?

HowCanCompaniesPayforBeautyandSurvive?

DoCompanieswithBetter-LookingCEOsPerformBetter?

BeautyHelpsCompanies—Probably

CHAPTERVILookismorProductiveBeauty,andWhy?

WhattheBeautyEffectMeans

HowCanBeautyEffectsBeDiscrimination?

HowCanBeautyBeSociallyProductive?

WhatAretheSourcesofBeautyEffects?

WhatIstheDirectEvidenceontheSources?

TheImportanceofBeauty

PARTIIIBeautyinLove,Loans,andLaw

CHAPTERVIIBeautyinMarketsforFriends,Family,andFunds

BeyondtheLaborMarket

HowIsBeautyExchanged?

HowDoesBeautyAffectGroupFormation?

HowDoesBeautyAffectDating?

HowDoesBeautyAffectMarriage?

CouldThereBeaMarketforBeautifulChildren?

DoesBeautyMatterWhenYouBorrow?

TradingBeautyinUnexpectedPlaces

CHAPTERVIIILegalProtectionfortheUgly

FairnessandPublicPolicy

WhatKindsofProtectionArePossible?

HowHaveExistingPoliciesBeenUsed?

IsItPossibletoProtecttheUgly?

WhatJustifiesProtectingtheUgly?

WhatJustifiesNotProtectingtheUgly?

WhatIsanAppropriatePolicy?

ProtectingtheUglyintheNearFuture

PARTIVTheFutureofLooks

CHAPTERIXProspectsfortheLooks-Challenged

TheBeautyConundrum

AreBeautifulPeopleHappier?

WhatWillBeBeautiful?WhatShouldBe?

WhatCanSocietyDo?

WhatCanYouDoIfYou’reBad-Looking?

Notes

Index

PREFACE

I got involved instudyingtheeconomicsofbeautyinacuriousway.Earlyin

1993, I noticed that the data I was using on another research project included

interviewers’ ratings of the beauty of the survey’s respondents. I thought it

would be fun to think about how beauty affects earnings and labor markets

generally.TheresultwasthefirstofthesixrefereedscholarlypapersthatIhave

publishedonthistopic.Aseriousdifficulty formein thislineof researchhas

beenthatmanyeconomistsfindworkonthistopic,andeventhiskindoftopic,

tobebeyondthescopeofeconomicresearch.Thatkindofnarrow-mindedness

hasconspiredinthepasttomakeeconomicsappearboringintheeyesofmany

non-economists.AstheworkofGaryBecker,SteveLevitt,and,toamuchlesser

extent,myownhasshown,economicresearchcanbeanythingbutboring.Many

ofthetopicsthatweworkon,andonwhichseriouseconomicthinkingcanshed

light,arefunandinvolveissuesthatcouldnotbeunderstoodusingthemethods

ofanyotherscholarlydiscipline.

Ibeganworkingnearlytwentyyearsagotodiscoverwhateconomicshasto

sayonthetopicofphysicalappearance.Manyofthethemesthatarediscussed

inthisbookwerefirsttestedoutinscholarlypapers,andlaterbecamepartofan

ever-evolving lecture that I have delivered in various venues, entitled “The

EconomicsofBeauty.”Indevelopingthescholarlypapersandinpresentingthe

public lecture, I have received numerous comments from listeners, both other

economistsand the smartpeoplewho happened toshowup to hearme.Large

numbersofthecommentshavebeenuseful;andevenwheretheyhavenotbeen,

they have still been fun to receive. Perhaps themost amusing was acomment

fromadistinguishedeconomistwhoasked,“Areyousurethatbeautyisn’tjust

correlated with early-birdness [a term whose meaningwas initiallycompletely

opaque to me and most of the audience,but presumably alludes to earlybirds

catchingworms]?”

Iwasnotthefirst to look at the relationship betweenbeautyandeconomic

outcomes—that’s an old topic. I was, however, the first to examine it using a

nationally representative sample of adults, and to do so in the context of

economic models of the determination of earnings. My subsequent work

broadenedthisapproachintoaresearchagendathatinquiredintothe“Why?”of

this relationship and, more generally, into the meaning of discrimination as

perhaps represented by the economic roles of beauty and ugliness. As one

formerstudentofmineputit,allofthishasledtothedevelopmentofasubfield

thatonemightdubpulchronomics.

Many of my colleagues have contributed indirectly to this book. The most

importanthavebeenthecoauthorswhohaveworkedonbeautytopicswithme,

includingthestudentsCiskaBosmanandAmyParker,andmyfriendsXinMeng

andJunsenZhang.CrucialthroughouthavebeenJeffBiddleandGerardPfann,

who have become the most frequent coauthors in my now forty-three-year

professional career. Seminar attendees at a very large number of universities,

and especially at the National Bureau of Economic Research Labor Studies

meetings,havemadecommentsthathaveimprovedsomeofthepapersIdiscuss

inthisvolume.MylaboreconomistcolleaguesGeraldOettingerandSteveTrejo

were also very generous with theirtimetolistentomyideas,aswasMelinda

Moore.

The authors of all the economic studies that have been published since the

early1990shavealso,withoutintendingit,contributedsubstantiallytothework.

Threereviewersofanearlierdraftofthemanuscriptmadecogentcommentsthat

greatlyimprovedthepresentation.Particularcontributionstothebookwerealso

madebyJudithLanglois,ViceProvostattheUniversityofTexasatAustin,and

probably the leading expert on the perception of beauty by infants. My law

professorbrothermade helpful comments on chapter8,andat age ninety-one,

my late mother, Madeline Hamermesh,solved mysearch for a good title.Her

contributionisthefirstthingthatthereadersees.

Usingthe5to1scalethatIdiscussinchapter2,Iama3.Inmyeyes,my

wifeofforty-fouryears,FrancesW.Hamermesh,isa5.(Idid,however,make

themistakeofcommentinginawidelycirculatednewspaperinterviewthatshe

was not Isabella Rossellini,nor was I AlecBaldwin.) She has encouragedmy

work on thistopic over nearly twodecades. Still more important,she made it

clearwhenitwastimetostopproducingnewworkandmaketheentireoeuvre

accessibleoutsidethenarroweconomics specialty.Hercommentsonall drafts

ofthemanuscriptimprovedittremendously.Idedicatethisbooktothisamazing

woman:Shewalksinbeauty,likethenightOfcloudlessclimesandstarryskies:

Andallthat’sbestofdarkandbrightMeetinheraspectandhereyes:

Thesmilesthatwin,thetintsthatglow,Buttellofdaysingoodnessspent,

Amindatpeacewithallbelow,

Aheartwhoseloveisinnocent!

“SheWalksinBeauty,”GeorgeGordon,LordByron

DanielS.Hamermesh,Austin,TexasNovember2010

PARTI

Background

toBeauty

CHAPTER1

TheEconomicsofBeauty

Modern man is obsessed with beauty. From the day we are old enough to

recognizeourfacesinamirroruntilwellaftersenilitysetsin,weareconcerned

with our looks. A six-year-old girl wants to have clothes like those of her

“princess”dolls;apre-teenageboymayinsistonahaircutinthelateststyle(just

asIinsistedonmycrewcutin1955);twenty-somethingsprimpatlengthbefore

a Saturday night out. Even after our looks, self-presentation, and other

characteristicshavelandedusamate,westilldevotetimeandmoneytodyeing

our hair, obtaining hair transplants, using cosmetics, obtaining pedicures and

manicures,anddressingintheclothesthatwespentsubstantialamountsoftime

shopping for and eventually buying. Most days we carefully select the right

outfitsfromourwardrobesandgroomourselvesthoroughly.

The average American husband spends thirty-two minutes on a typical day

washing, dressing, and grooming, while the average American wife spends

forty-four minutes. There is no age limit for vanity: Among single American

womenageseventyandolder,forsomeofwhomyoumightthinkthatphysical

limitationswouldreducethepossibilityofspendingtimeongrooming,wefind

forty-three minutes devoted to this activity on a typical day.

1

Many assisted

living facilities and nursing homes even offer on-site beauty salons. For most

Americans, grooming is an activity in which they are willing to invest

substantialchunksoftheirtime.

Wenotonlyspendtimeenhancingourappearance—wespendlargesumsof

money on it too. In 2008, the average American household spent $718 on

women’sandgirls’clothing;$427onmen’sandboys’clothing;$655oninfants’

clothing, footwear, and other apparel products and services; and $616 on

personalcareproductsandservices.

2

Suchspendingtotaledroughly$400billion

andaccountedfornearly5percentofallconsumerspendingthatyear.Nodoubt

some of this spending is necessary just to avoid giving olfactory or visual

offensetofamilymembers,friends,andotherswhomwemeet;butthatminimal

amountisfarlessthanweactuallyspendontheseitems.

There is nothing uniquely modern or American about concerns about dress

and personal beautification. Archaeological sites from 2500 BCE Egypt yield

evidence of jewelry and other body decoration, and traces of ochre and other

bodypaintsarereadilyavailableevenearlier,fromPaleolithicsitesinsouthern

France.Peopleinotherindustrializedcountriesearlyinthetwenty-firstcentury

show similar concerns for their appearance and beauty: For example, in 2001

German husbands spent thirty-nine minutes grooming and dressing, while

German wives spent forty-two minutes in these activities, quite close to the

American averages. This similarity is remarkable, since you would think that

cultural differences might lead to different outcomes.

3

It suggests the

universalityofconcernsaboutbeautyanditseffectsonhumanbehavior.

The public’s responses to beauty today are fairly similar across the world.

TheChineseproducersofthe2008SummerOlympicsmusthavebelievedthis

whentheyputan extremely cute nine-year-old girlonworldwide television to

lip-syncthesingingofalessattractivechildwhohadabettervoice.

4

Thesame

attitudes underlay the worldwide brouhaha about the amateur English singer,

Susan Boyle, whose contrasting beautiful voice and plain looks generated

immensemediaattentionin2009.

Ourpreoccupationwithlookshasfosteredthegrowthofindustriesdevotedto

indulging this fascination. Popular books have tried to explain the biological

basisforthisbehaviorortoexhortpeopletogrowoutofwhatisviewedasan

outdated concern for something that should no longer be relevant for purely

biologicalpurposes.

5

Newsstandsineverycountryareclutteredwithmagazines

targeting people of different ages, gender, and sexual preference, counseling

their readers on methods to improve their looks. A typical example from the

coverofalifestylemagazineforwomenoffersadviceon“BeautySecretsofthe

Season.”Oneofitscounterpartscounselsmen onhowto“GetFit,Strongand

Leanin6Weeks.”

6

Theimportanceofbeautyisevidentintheresultsofatelephonesurveyinthe

United States.

7

Among the randomly selected people who responded to the

survey, more felt that discrimination based on looks in the United States

exceeded discrimination on ethnicity/national background than vice-versa.

Slightly more people also reported themselves as having experienced

discriminationbasedontheirappearancethanreporteddiscriminationbasedon

theirethnicity.AverageAmericansbelievethatdisadvantagesbasedonlooksare

realandeventhattheyhavepersonallysufferedfromthem.

Allwellandgood—thetimeandmoneythatwespendonitshouldenhance

ourinterestinbeautyanditseffects,andwe areworriedaboutandexperience

negativefeelingsifourlooksaresubpar.Butistheconcernofeconomistsmore

thanjustaprurientoneinresponsetothisintriguingtopic?Partoftheanswerto

this question stems from the nature of economics as a discipline. A very

appealingcharacterizationisthat economicsis thestudyofscarcityand ofthe

incentivesforbehaviorthatscarcitycreates.Aprerequisiteforstudyingbeauty

asaneconomicissuemustbethatbeautyisscarce.Forbeautytobescarce,as

buyersofgoodsandrentersofworkers’timepeoplemustenjoybeauty.Ifthey

cannotfindsufficient beauty suppliedfreely,and are thereforewillingto offer

moneytoobtainmoreofit,itmustbethatbeautyisscarce.

Take as given the notion that the scarcity of beauty arises from genetic

differencesinpeople’slooks,sothatbysomesociallydeterminedcriteriasome

people are viewed as better-looking than others. (I discuss what I mean

operationallyby“beauty”inthenextchapter.)Wouldbeautystillbescarceifwe

wereallgeneticallyidentical?Ofcourse,thiseventualityisnotabouttooccur,

butevenunderthisunrealisticscenarioitwouldstillmakesensetotalkaboutan

economics of beauty. So long as people desire to distinguish themselves from

others, someofthesehypotheticalcloneswillspend more on their appearance

thanothersinordertostandoutfromthecrowd.SomeofDr.Seuss’sSneetches

—a tribe of birdlike creatures who look identical—illustrate this desire for

distinctionalongonedimensioninthefaceofboringsamenessalongallothers

byputtingstarsontheirbellies.Theterm“scarcebeauty”isredundant—byits

nature,beautyisscarce.

The other part of the answer to this question stems from what I will

demonstrate are the large number of economic outcomes related to beauty—

areaswheredifferencesinindividuals’ beauty can directly influence economic

behavior.Marketsforlaborofavarietyoftypes,perhapsevenalllabormarkets,

mightgeneratepremiumpayforgoodlooksandpaypenaltiesforbadlooks.The

measurement of pay premia and penalties in different jobs and for people

belonging to different demographic groups is a standard exercise among

economic researchers. Doing so in the case of beauty is a straightforward

application.

Witheveryeffectonthepriceofagoodorservice,inthesecaseswagerates,

which are the prices of workers’ time, there is an effect on quantity. How a

personal characteristic alters the distribution of workers across jobs and

occupations is standard fodder for economists; and beauty is surely a personal

characteristic that can change the kinds of jobs and occupations that people

choose.

Ifbeautyaffectsbehaviorinlabormarketsandgeneratesdifferencesinwages

and the kinds of jobs that we hold, it may also produce changes in how we

choosetouseourtimeoutsideourjobs.Howwespendourtimeathomeisnot

independentofhowwespendourtimeatworkorofthekindsofoccupationswe

choose.Ifdifferencesinbeautyalteroutcomesintheworkplace,theyarelikely

toalteroutcomesathometoo.

A characteristic like beauty that affects wages and employment will also

affectthebottom line of companies andgovernmentsthatemploy the workers

whose looks differ. Are certain industries likely to be more significantly

affected? How does the existence of concerns about beauty affect companies’

salesandprofitability?Howisexecutives’payaffectedbytheirbeauty?Perhaps

mostimportant,howcancompaniessurviveifbeautyisscarceandthusaddsto

companies’costsandpresumablyreducestheirprofitability?

Themorebasicquestioniswhythesedirecteffectsonlabor-marketoutcomes

arise.Whosebehaviorgeneratestheoutcomesthatwehopetomeasure?Aside

from allowing us to measure the importance of the phenomenon of beauty in

economicbehavior,economicsasapolicyart/scienceshouldbeabletoisolate

themechanismsbywhichitaffectsoutcomes.Itiscrucialtoknowhowbeauty

generates its effects if we are to guard against giving undue importance to its

role in the functioning of labor markets. It is also important in weighing the

benefitsandcoststosocietyofourattitudesabouthumanbeauty.

Allofthesepossibleeconomicinfluencesofbeautyaredirectandareatleast

potentially measurable. And those measurements can readily be made in

monetaryterms,oratleastconvertedintomonetaryequivalents,sothatwecan

obtainsomefeelforthesizeoftheimpactsrelativetothoseofothereconomic

outcomes.Becauseofthescarcityofbeauty,itseffectsoutsidemarketsforlabor

andgoodscanalsobestudiedineconomicterms.Marriageisjustsuchamarket,

althoughhusbandsandwivesarenotboughtorsoldinrichcountriestoday.Yet

theattributesthatwebringtothemarriagemarketaffecttheoutcomesweobtain

inthatmarket,specificallythecharacteristicsofthepartnerwhowematchwith.

Beautyisoneofthoseattributes,soitisreasonabletoassumethatdifferencesin

thebeautythatwebringtothemarriagemarketwillcreatedifferencesinwhat

wegetoutofit.Wetradeourlooksforotherthingswhenwedateandmarry;but

whatarethoseother things, and how much of themdoourlooks enable us to

acquire?

Takingallofthistogether,theeconomicapproachtreatsbeautyasscarceand

tradable. We trade beauty for additional income that enables us to raise our

living standards (satisfy our desires for more things) and for non-monetary

characteristicsofworkandinterpersonalrelations,suchaspleasantcolleagues,

anenjoyableworkplace,andsoon,thatalsomakeusbetteroff.Researchersin

other disciplines, particularly social psychology, have generated massive

amounts of research on beauty, occasionally touching on economic issues,

particularlyinmarriagemarkets.Buteconomistshaveaddedsomethingspecial

and new to this fascinating topic—a consistent view of exchange and value

relatedtoacentralhumancharacteristic—beauty.

Theeconomicsofbeautyillustratesthepowerofusingverysimpleeconomic

reasoning to understand phenomena that previously have been approached in

otherways.Thatpower,thetimeandmoneythatarespentonbeautyworldwide,

and human fascination with beauty, are more than sufficient reasons to spend

time thinking about beauty from an economic point of view. The economic

approachtobeautyisanaturalcomplementtoeconomicresearchonlessgeneral

topicssuchassuicideandsumowrestling,sleepandcommercialsex.

8

I concentrate on economic issues, introducing studies from the psychology

and other literatures only where they amplify the economics or contribute

essential foundations to understanding the economics of beauty. These other

approaches are important; they have provided many insights into human

behaviorandgarneredalotofmediaattention.Butbecausetheydonotrestona

choice-basedeconomicapproach,theycannotprovidetheparticularinsightsthat

economicthinkingdoes.

9

The economic approach is broad, but not all-encompassing. Economic

analysiscannotexplainwhatmakessomepersonalcharacteristicsattractiveand

othersnot—orwhythesameindividual’slooksevokedifferentresponsesfrom

eachdifferentobserver.Wetakethesourcesofdifferencesinpreferencesinthe

samecountryandatthesametimeasoutsideourpurview.Itdoesnotdescribe

how responses to personal characteristics differ over the centuries or among

societies.Ittreatsthesetooasgiven.Butknowingwhathumanbeautyis—what

aretheattributesthatmakethetypicalonlookerviewsomepeopleasattractive

andothersasnot—istheessentialpre-conditionforthinkingabouttheeconomic

impacts of beauty. For that reason, the next chapter describes what we know

about the determinants of human beauty, a topic that has received a lot of

attentionfromsocialpsychologistsandthatunderlieswhateconomicshastosay

abouttheroleofbeauty.

CHAPTER2

IntheEyeoftheBeholder

DEFINITIONSOFBEAUTY

Whatishumanbeauty?Howdoesbeautyvarybygender,race,andage?Most

important,doobservershaveatleastsomewhatconsistentviewsofwhatmakes

apersonbeautiful?Inordertoanswerthesequestions,wefirstneedtoattemptto

definebeauty.Oneonlinedictionaryoffersadefinitionofbeautythatisrelevant

forourpurposes:“Thequalityoraggregateofqualitiesinapersonorthingthat

givespleasuretothesensesorpleasurablyexaltsthemindorspirit.”

1

Theterm

“aggregate of qualities in a person” comes close to describing beauty in an

economiccontext;butitstillleavesthedefinitionvagueforpracticalpurposes—

whatqualities,whataggregate?“Beautyisintheeyeofthebeholder,”thefirst

stockphrasethatcomestoyourmindwhenaskedabouthumanbeauty,suggests

thatpeople’sopinionsaboutthisquestionofhumanbeautydiffer.

Foreconomicpurposesthequestionsarewhatcharacteristicsmakeaperson

beautiful, and do people agree on what these characteristics are and what

expressionsofthemconstitutehumanbeauty.YouandImaydifferinourviews

about what beauty is. But if our views about human beauty are somewhat

similar, and we are typical individuals, then our opinions are valuable

representativesofhowthegeneralpopulationviewsbeauty.Andifweexamine

how people have viewed beauty over the ages, we can acquire a more

sophisticated understanding of what humanbeauty isand havemore informed

opinionswhenwejudgepeople’slooks.

Even if people agreed completely on what expressions of various

characteristicsconstitutebeauty,wewouldstillneedtodecidewhichparticular

constellationofcharacteristicsshouldbeconsideredinthedefinition.Isithairor

hair color? Weight? Height? Physiognomy—just the face? Internal beauty—

character and its expression—reversing the popular saying that beauty is only

skindeep?Isitgenerosity?Sympathy?Facialexpression?Dress?Combinations

ofthese?Todiscusstheeconomiceffectsofbeauty,Iwanttonarrowthefocus

asmuchaspossibletofaces.Onemightarguethatphysiognomyrepresentsonly

atinypartofhumanbeauty—andthatiscorrect.Nonetheless,physiognomycan

beisolatedandusedasabasisforjudgmentsabouthumanbeauty:

She reminded me of the daughter that I always had wished for. Bright

eyes, a mouth ready to laugh, high cheekbones and luxurious shoulder-

length brown hair. The photo didn’t show if she was short or tall, fat or

thin,bentorerect—itwasonlyapassportphoto.

2

Or,asthepsychoanalystOliverSacksputit,“itistheface,firstandlast,thatis

judged‘beautiful’inanaestheticsense.”

3

Asthesequotationssuggest,peoplecananddomakejudgmentsaboutbeauty

based only on physiognomy. Throughout this book I examine how judgments

aboutthisonemanifestationofbeautyaffectbehavior.

No doubt standards of beauty do change over time. The Renoir nudes that

enthralled the art world from the 1880s through the early twentieth century

wouldnotberegardedasgreatbeautiestoday—whilenotunattractive,theyare

probablytoozaftigforcontemporarytastes.Ontheotherhand,late-nineteenth-

centuryobservers almostcertainly wouldhave regardedtoday’s modelson the

runways of Parisian haute couture as incipiently consumptive, perhaps a

character out of La Bohème (just as my late grandmother, born in Europe in

1887, viewed my thin face as suggesting that I am dangerously underweight).

Evenwithinasociety,standardsoffacialbeautydochangeovertime.Standards

alsodiffer,oratleastusedtodiffer,acrosssocietiesatroughlysimilarpointsin

time.Thegentlemaninfigure2.1isRudolfValentino,theHollywoodheartthrob

ofthe1920s.Mostpeopleeventodaywouldagreethathewasquitebeautiful—

presumablythatwasamajorunderpinningofhissuccessasamovieactor.The

gentleman in figure 2.2 also lived in the early twentieth century, but in the

Arctic.Whilehis fellows would haveagreedthathe is beautiful, itisunlikely

thathislookswouldhavelandedhimaHollywoodmoviecontract.

Within a society at a point in time, including the worldwide society of

developed nations, there is substantial agreement on what constitutes human

beauty. I asked three women, ages twenty, thirty-five, and sixty-five, who the

sexiestmenintheworldaretoday.AllthreeincludedGeorgeClooneyintheir

list.Havingpresentedhispictureandthoseofanumberofothermen,including

Asian and American politicians and actors, to audiences in the United States,

Asia,Australia,andEurope,Iamcertainthatthereisnearlyuniversalagreement

thatGeorgeClooneyisconsideredbetter-lookingthanalmostanyoneelse.

Figure2.1.RudolfValentino,actor,1920s.©Bettmann/CORBIS

Figure2.2.Inuitman,1920s.PhotofromMaritimeHistoryArchive,MemorialUniversityof

Newfoundland,St.John’s,NL.

It is not that George Clooney is a Westerner and there is some kind of

universalprejudiceinfavorofWesternfaces.Takethetwowomeninfigures2.3

and 2.4. I would wager that most readers, be they Western or not, would

considerSouthCarolinagovernorNikkiHaley,whoisofSouthAsiandescent,

much better-looking than U.S. senator Barbara Mikulski. These cases at least

provideanecdotalevidenceofthecurrentnear-universalityoftoday’sstandards

ofhumanbeauty.

Figure2.3.NikkiHaley,U.S.politician,2000s.APPhoto/AlexBrandon,File.

Cultural differences do still exist. A recent report on a “fat farm” in

Mauritania, one of the poorest countries in the world, illustrates their

persistence.

4

Thisisnotthekindof “fatfarm” towhichrichNorthAmericans

retreattoloseweight,butonewhereyounggirlsarefed,andevenforce-fed,to

producerotundyoungadultswhoareviewedasattractive.Buteventhisunusual

cultural difference appears to be diminishing in importance as Mauritania

industrializesandbecomesmoreintegratedwiththeoutsideworld.

5

Figure2.4.BarbaraMikulski,U.S.politician,2000s.OfficialgovernmentphotofromtheU.S.Senate

HistoricalOffice.

WHYDOBEAUTYSTANDARDSMATTER?

Unlesspeopleagreeonwhatconstituteshumanbeauty—unlessthereisatleasta

somewhat common standard of beauty—it cannot haveany independenteffect

onoutcomessuch as earnings.Itmight seemtohave an effect,evenif people

disagreedaboutbeauty,butthatcouldonlybeifothercharacteristicsthataffect

thoseoutcomesarerelatedtobeauty.

These same arguments apply to the role of beauty in other areas in which

humanbeingstrade.Wetradeourcharacteristicswhenweenterintoamarriage.

AsthestoryofJacob’seffortstowinthehandofRachel“ofbeautifulformand

fair to look at” illustrates, throughout human history men who can raise more

sheep,producemorecrops,orearnmoredollarsinthestockmarkethaveused

thesecharacteristicstoobtainmoredesirable(and,insomesocietiesandepochs,

more)wives.

6

Ifmenagree on feminine beauty, just as inlabormarkets those

womenviewedasbeautifulwillcommandahigherprice,eitherexplicitlyorin

the form of husbands who can provide them with more resources. They will

obtainmoreandbetterfood,aneasierlifestyle,morefreedomtodowhatthey

want,andotherbenefits.Asmenandwomenbecomemoreequaleconomically,

solongaswomenhavecommonviewsaboutmen’sbeauty,thesamebehavior

will apply in reverse: Women who have more to offer men, including the

economicadvantagestheycanofferprospectivehusbands,willobtainthebetter-

lookinghusbands.

Solongastherearecommonstandardsofbeauty,theywillaffectoutcomes

inanymarketwherebeautyaffectstransactions—whereitaffectswhatistraded.

Thatisastrueforhiringworkersasitisformarriagecontracts.Thequestionfor

analyzingtheeconomiceffectsofbeautyiswhethertheideaofcommonbeauty

standardsisrepresentedbymorethanjustthepictorialanecdotespresentedhere.

Do people agree, at least to some extent, on which of their fellows are good-

lookingandwhicharenot?Dotheysharecommonviewsofhumanbeauty?

HOWDOWEMEASUREHUMANBEAUTY?

Wecan’tseewhethertherearecommonstandardsofbeautyunlessweareable

tocomparedifferentpeople’sviewsaboutbeauty.Andwecan’teasilycompare

them unless we can somehow measure them. The difficultyis that thereis no

singlewaytoattachnumericalscorestoobservers’beliefsaboutthebeautyof

thepeopletheysee.WhenIwasaseniorinhighschoolwereadMarlowe’sDr.

Faustus, in which the title character describes a vision of Helen of Troy and

declaims,“Isthisthefacethatlaunch’dathousandships,andburntthetopless

towers of Ilium?” This prompted one of my fellow nerds to suggest that we

shouldmeasurethepulchritudeofthegirlsinourclassinmilli-Helens!Thisis

as reasonable a subjective measuring device as another, but perhaps

unsurprisinglyithasnotbeenappliedinresearchonbeauty.

One might, for example, use a numerical rating scheme and use a 10 to 1

scale.Onemightinsteadusea5to1scale.Toseethatthesearenotthesame,

lookatthenextfivepeopleyouseeandgiveeachonearatingona5to1scale.

Askyourselfafterward:“IfIhadinsteaduseda10to1scale,wouldmyratings

just have been double those that I gave on the 5 to 1 scale?” I doubt it. In

particular, I would bet that scores of 10 on the 10 to 1 scale would be

substantiallylessfrequentthanthetopscoreonthe5to1scale.

Inaskingonlookerstoratepeople’sbeauty,doweattachverbaldescriptions

to the numerical ratings that observers are asked to give, or are they simply

askedtochooseascore?Evenwiththesamescale,say5to1,theanswerswill

differdependinguponwhat,ifanything,theobserveristoldaboutthemeaning

ofthescores.

What are the observers asked to rate—people standing in front of them, or

pictures? Both approaches have been used, and the difference between them

formsthemainunderlyingdistinctionamong studies of beauty. Ratings of the

same person by the same observer will differ between the two methods. The

picture may show her looking radiant upon her college graduation, or him

beamingonhisweddingday.Peopledonotreactthesamewaytothecamera,

and it is impossible to adjust for differences in their reactions when we use

observers’ratingsofpictures.Somemaybedressedwellforthepicture,others

dressedsloppily.Somemaybecapturedscowling,whileothershaveasmilethat

isglowingenoughtoturna4intoa5.

Assumingthatwerelyonratingsofpictures,whataretheypicturesof?What

are the observers asked to rate?Faces alone? Headand shoulders?Full body?

Posed or not? Since I have defined beauty for the purpose of this study as

physiognomy, head and shoulders, or even the face alone, would be best; but

pictureslikethatarenotalwaysavailable.

Theproblemisequally,but differently,challengingifwerelyonratingsof

peoplewhoarebeinginterviewedface-to-face.Ifnothingelse,andevenwiththe

mostexplicitinstructions,interviewerswilltendtobasetheirassessmentsonthe

natureoftheinteractionsthattheyhavealready hadwiththeperson.Does the

intervieweeanswerthedoorinadresssuit,orinasweatsuitpost-workout?Is

sheattheendofatiringday,orisshefreshandreadytodealwithwhateverthe

world may bring? All of these variations in appearance and behavior will

conditionhowtheinterviewerassessesherlooks.

With both photographs and interviews, it is impossible to be sure that the

raterisbasingtheratingsolelyonphysiognomy.Arestrictiontophysiognomyis

more likely with pictures, but even there, weight may enter into the rating

(remembertheRenoirmodel).Intheend,itisimpossibletorestrictratingstobe

objective—the rating of beauty is inherently subjective. People will always

disagreetosomeextent.

While there may be universal standards of beauty, and thus substantial

agreementonwhatisbeautiful,therearenouniversalstandardsonhowpeople

indifferentcountriesandculturesrespondwhenconfrontedbywhatappeartobe

identical requests to rate others’ beauty. Even with the best translation, what

appeartobethesameratingsystemsmay havedifferentmeanings indifferent

societies. And there may be international differences in raters’ generosity or

willingnesstomakefinedistinctions.

There is no way of avoiding these problems. The best we can do in

interpreting studies of the effects of beauty is to be sure that raters of beauty

were monitored so that they adhered to strict guidelines that are at least

internallyconsistentwhentheyprovidedtheirratings.

Themostwidelyusedscaleinthebeautyliteraturehasbeena5to1rating

scheme, usually with instructions to the interviewers/raters about what these

ratingsmean.Thenumericalscoresweredefinedininstructionstointerviewers

in a nationally representative 1971 survey conducted by the University of

Michigan. They have been used with minor variations in many subsequent

studies,boththosebasedonobservationsduringliveinterviewsandthosebased

onratingsofphotographs.

7

NeartheendofalengthyinterviewintheMichigansurvey,theinterviewer

wasinstructedto“ratetherespondent’sphysicalappearance”usingthescale:

5 Strikinglyhandsomeorbeautiful

4 Good-looking(aboveaverageforageandsex)

3 Averagelooksforageandsex

2 Quiteplain(belowaverageforageandsex)

1 Homely

Notetheparentheticalqualifiersthatwereincludedtoinducetheinterviewersto

abstract from preconceptions that they might have about age or gender

differencesinlooks.

Togetafeelfortheuseofthisratingscheme,lookatthenexttenstrangers

you see and try rating their looks along this scale. Don’t intellectualize about

your rating—as the interviewers did, it should be a snap response to your

impressions.Iwouldbesurprisedifyoucannoteasilydistinguisha“4”froma

“2”amongthepeopleyouencounter.

IwasobsessedbythesedatainthefirstfewdaysafterIdiscoveredthem.I

walked around my campus mentallyrating the beauty of mostof the people I

passedonthis5to1scale.IadmitthatIalsoratedmycolleagues’looksonthis

scale,thusviolatingtheanonymitythat should exist between subject and rater

butthatisnecessarilyviolatedinratingsbasedoninterviews.

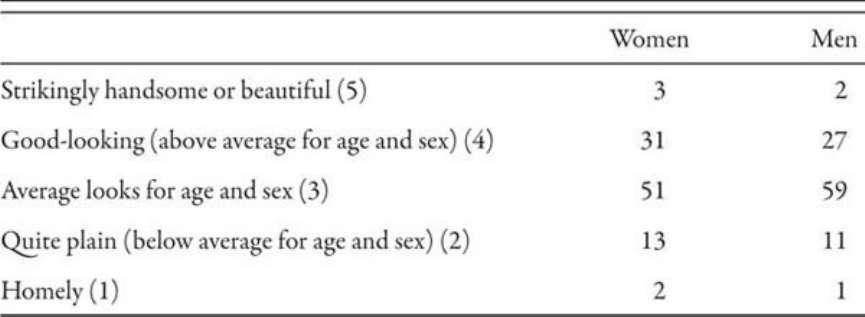

Thedistributionsoftheseinterviewers’ratingsalongthe5to1scaleinthis

studyandinarelatedstudyconductedlaterinthe1970sareshownintable2.1,

separately for men and women. Here, as in many subsequent tabulations of

ratingsofbeautybasedoninterviews,moreindividualsareassessedasbeingin

the top two categories than inthebottom two. Interviewers’ formal subjective

ratings of beauty are not quite characterized by a Lake Wobegon effect—not

everyone is above average in beauty—but the average person whose beauty is

assessedinthisstudyisconsideredaboveaverage.

TABLE2.1

RatingsofAppearance,QualityofAmericanLife,andQualityofEmploymentSurveys,AmericansAges

18–64,1970s(percentdistributions)*

*Tabulationsfromrawdatadescribing1,495womenand1,279men.

Interviewer-based ratings from vastly different cultures produce the same

generalresults.EvidencefromasurveyinShanghai,China,fromthemid-1990s

demonstratesthesimilarityofratingstothoseintheUnitedStates.TheChinese

interviewers were, though, particularly unwilling to rate people as below-

averageinlooks—only1percentofmen,and1percentofwomen,wereratedas

below-averageorugly.Nearlytwo-thirdsofeachgroupwasratedasaverage.

Using the same 5 to 1 scale as in table 2.1, raters examined nearly 2,500

photographs of students who entered a large, prestigious law school between

1969and1984.Eachphotograph(typicallyhead-and-shouldersshots)wasrated

byfourdifferentobservers.Aswiththeinterviewratings,nearlyhalfthepeople

wereratedasaverage-looking.

The 5 to1 scale ora minor variant is most common, but others have been

used. One study asked six raters (three male and three female undergraduate

students)tousea10to1scaletoexaminephotographstoassessthelooksofa

groupofninety-fourprofessors(whomthesixstudentsdidnotknow).

8

Asinthe

lawstudents’study,therewasnotendencytoratetheprofessors’looksasabove

themiddle ofthe 10-pointscale—indeed,morewererated 5or lessthanwere

rated6orabove.Partlythismaybeduetotheprofessors’ages(averagingfifty)

beingso differentfromthose oftheundergraduates doingtheratings. Partlyit

mayjustbethesample:Whenaskedwhyhisratingswereparticularlylow,one

malestudentremarked,“Becausetheseprofsarereallyugly!”

DOOBSERVERSAGREEONBEAUTY?

That people are biased in favorof judging others’ beauty as onaverage being

above-average,orevenasbelow-average,isnotaproblem—itiseasytoadjust

statistically for these biases in drawing conclusions about the relationship

betweendifferencesinbeautyandanyeconomicorotheroutcome.Thetougher

questioniswhetherpeopleagreeonthebeautyofaparticularindividual,andthe

extent of that agreement, if any. Without that there would be no common

standards of beauty. Beauty would have no meaning in an economic context,

since its diffuseness would mean it could not be scarce. And I would not be

writingthisbook!

Therearetwodifferentwaystodiscovertheextentofraters’agreementabout

people’s beauty. The first,which has been usedonly rarely, is tolook at how

raters’assessmentsofpeople’sbeautyvarywhentheyviewthesameindividuals

atdifferenttimes.Answersusingthisapproachcanbeseenfromastudybased

onpicturesofeconomists.Iaskedfour studentswho werejust beginningtheir

graduate studies to rate the looks of a large number of pictures of leading

economists, many of whom were included multiple times and submitted a

differentphotographeachtime.Ofcourse,thesameindividualreceiveddifferent

ratingsfordifferent pictures,butthose differencesweresmallcomparedtothe

differencesintheaverageratingsreceivedbydifferenteconomists.

9

Answers based on interviews can be seen from a nationally representative

studyundertakeninCanada,inwhichthesamepeoplewereinterviewedin1977,

1979,and1981.Eachindividualwascontactedbyadifferentinterviewerineach

year,allowinganopportunityfordifferentviewsoftheinterviewee’slookstobe

expressed. The interviewerswereaskedtoassess looks using the 5 to 1 scale.

Comparing ratings in adjacent years, 54 percent of women and 54 percent of

men were rated identically in each of the two years; and only 3 percent of

womenand2percentofmenreceivedaratinginthesecondyearofapairthat

differedbymorethan1fromtheratingthattheyhadreceivedinthefirstyearof

thatpair.

10

Evenindifferentinteractionswithdifferentinterviewerstherewasa

remarkabletendencytoviewtheinterviewees’looksverymuchthesameway.

Thesecondwayoftestingforconsistencyinourviewsofothers’beautyisto

ask a group of individuals to provide independent ratings of another person’s

looks. Typically this has been done by showing each of a number of people,

noneofwhomcancontacttheothers,thesamephotograph.Whiletherewillbe

disagreements, the question is whether they are small, so that the averages

informusaboutgeneralperceptionsofeachperson’slooks.

Asanexample,taketheratingsofthelawstudents’photosdescribedearlier.

Complete agreement—all four observers giving the exact same score to a

photograph—wasfairlyuncommon,occurringforonly14percentofthephotos.

Butnearagreement,definedasallfourratingsthesame,asthreeoffourraters

ratingthepictureidentically,orastwopairsofraterswhodifferbyonly1point

on the 5-point scale, occurred with the photos of 67 percent of the female

studentsand75percentofthemalephotos.Onlyone-tenthof1percentofthe

studentswererateddifferentlybyallfourraters.Completedisagreementabout

looksisanextraordinarilyrareevent.

Even in the case of the professors, where the 10 to 1 scale allows for a lot

moreminordisagreementamongthesixraters,54percentoftheprofessorswere

ratedidenticallybyatleastthreeofthesixraters.Amongtheeconomists,who

werealsoratedonthe10to1scale,28percentofthepicturesreceivedthesame

scorefrom threeof thefour raters,and 80percent wererated identicallyby at

leasttwoofthefour.

Thereareconsistentdifferencesinhowindividualsrateeachother’sbeauty.

Within the same culture some people are always harsh in rating their fellow

citizens’ looks, and others are consistently more generous. In the study that

establishedthe5-pointratingscheme,eachofsixtyinterviewersratedatleastten

subjects.Theaverageratingsranged from3.6 (closerto above-averagethanto

average)bythemostgenerousinterviewerdownto2.4(closertoplainthanto

average)bythemostnegativeinterviewer.Butonly10percentofthedifferences

intheratingsofintervieweescanbeascribedtojudgmentsbyraterswhoapplied

particularly harsh or generous standards. While interviewers do have different

standards,theeffectsoftheirdifferencesaredwarfedbytheinherentdifferences

inpeople’slooks.

11

About half of the interviewers in thatstudy were between ages twenty-two

andforty-nine,theotherhalfwerebetweenagesfiftyandseventy-four.Despite

their possibly different perspectives on the subjects’ looks, there were no

statistically meaningful differences in the ratings given by interviewers of

differentages. But while interviewers’age was independent oftheratings that

they assigned, there were differences by gender. Men seemed to be stingier

ratersofthesubjects’beauty.

There are also differences across countries, probably having to do with

culturaldifferencesinpeople’swillingnesstosaysomethingnegativeabouttheir

fellows.Forinstance,AmericansseemslightlymorewillingthantheirCanadian

neighbors to label someone as plain or homely. As noted earlier, in the

Shanghainese data, only 1 percent of the interviewees were rated as below

average. The only useful distinction in those data is between those rated as

averageandthoseratedasprettyorverypretty.

Despite these consistent disagreements and biases, the answer to the titular

question of this section is a resounding, “MOSTLY!” There is no universal

agreementbygroupsofpeopleonanyoneelse’sbeauty.Somepeopleareharsh

judgesofothers’looks,whileotherpeoplearegenerousintheirappraisals.But

individuals do tend to view others’ beauty similarly, although not identically.

Someone who is considered above-average in looks by one observer will be

viewed the same way by most other observers. Someone who a randomly

selectedpersonthinksisquiteuglywillbeviewedasquiteuglybymostother

observers. Yes, there are disagreements, but there is also a lot of agreement.

Thereisnouniqueviewaboutbeauty—nouniquestandard.Butbecausepeople

tendtoviewhumanbeautysimilarly,thosewhoaregenerallyviewedasgood-

looking possess a characteristic—their beauty—that appeals to most other

human beings in similar ways and that ipso facto is in short supply. Human

beautyisscarce.

DOESBEAUTYDIFFERBYGENDER,RACE,OR

AGE?WHATMAKESYOUBEAUTIFUL?

Arewomenbetter-lookingthanmen?IthinksowhenIthinkromantically,but

you no doubt have your own views on this subject. The question, though, is

whetherwethinkthatwaywhenwetrytoassesspeople’slooksobjectively.The

averagemaleinthedataunderlyingtable2.1wasratedalmostthesameasthe

average woman. In the Shanghai data, women were rated as slightly better-

lookingthanmen,withthedifferenceresultingfrommorewomenbeingratedas

beautiful.

This near equality only arises if the individuals being rated are chosen

randomly.Womenconstitutedonly12percentofthelawstudentswhoentered

theprestigiouslawschoolbetween1969and1974.Theaverageratingoftheir

lookswas3.1,comparedtothe2.8averageratingoftheirmalefellowstudents,

perhapsbecausethosefewwomenwerespecialinmanyotherways.Bythenext

decade,femalestudentshadincreasedto31percentoftheenteringclasses,and

thedifferenceinaveragelooksbetweenmaleandfemalestudentswasonlyhalf

aslargeasbefore.Selectionintothesamplecanproduceunequalaveragesofthe

ratingsofthelooksofmenandwomen.Butwheremenandwomenareroughly

equally represented among the subjects, the average ratings of men’s and

women’slooksareusuallynearlyidentical.

Whileaverageratingsoflooksareroughlyequalbygender,thedistributions

differ, as the columns in table 2.1 illustrate. Ratings of women’s looks were

moreextremethanratingsofmen’s:Morewereratedasplainorhomely,more

were rated as strikingly beautiful or above-average, and fewer were rated as

possessing average looks. Interviewers react more strongly to women’s looks,

both positively and negatively in other interview studies too; and in studies

examiningphotographs,womenarealsoviewedmoreextremelythanmen.For

example,14percentoftheratingsoffemaleprofessorswereabove7,whileonly

6percentoftheratingsofmaleprofessorswere.

Whether beauty differs by race is another concern—if, for example,

employersperceive AfricanAmericans’ beautydifferently fromthat ofwhites,

any differences in earnings related to race could be confounded by disparate

treatment based on looks rather on than on race per se. In the two American

studies from the 1970s the interviewers, nearly all of whom were white, gave

almostidenticalratingson averageto whitesand AfricanAmericans.Butthey

did rate subjects of different races differently, reacting more extremely to the

whitesthantotheAfricanAmericans.Thirteenpercentofwhiteswereratedas

plainorhomely,whileonly10percentofAfricanAmericanswere.Attheupper

end, 32 percent of whites were viewed as being at least above-average, while

only 28 percent of African Americans were. There may well be differences

betweenhow membersofother races—AsianAmericans,for example—would

beratedbythewhiteraters,butwejusthavenoinformationonthatpossibility.

Whetherweconsiderlooksbygenderorrace,wereachthesameconclusion.

Therearenodifferencesinaverages,butthedistributionsofratingsofwomen’s

looksaremoredispersedthan those of men’s, and of whites’ looks morethan

thoseofAfricanAmericans.

The same conclusion cannot be drawn about differences in ratings of the

beautyofpeopleofdifferentages.Ratingsofwomen,andofmenfromstudies

conductedinthe1970s,demonstratethatthelooksofyoungerpeoplearerated

onaveragemorefavorablythanthoseofolderpeople.Eventhoughinterviewers

wereexplicitlyinstructedtoadjust“forageandsex,”theycouldn’t.

The differences in ratings by age are not small. Of women in the 18–29

group, 45 percent were rated at least above-average, while only 18 percent of

women50–64wereratedthatfavorably,aremarkabledrop-off.Thedeclinein

perceived looks with age is smaller among men, with 36 percent of men ages

18–29 rated above-average, while 21 percent of men 50–64 were rated that

favorably.Ageisharsheronourperceptionsofwomen’slooks.

Thereisnothinguniqueaboutthedifferencesinperceivedbeautybyagein

ourWesternculture.EveninChina,wherethestereotypeisoneofgreatrespect

forolderpeople,youngerpeople’sbeautyisratedmorepositively.Theaverage

ratingofpeopleages22–34 intheShanghaidatawas3.5;thatofpeopleages

35–49 was 3.4, while people 50 and over received ratings that only averaged

3.3.

12

The Chinese observers were no more able to separate beauty from age

thantheirAmericancounterparts.

Whytheseagedifferencespersistisnotatopicforthisbook—theirexistence

isallthatisimportant,asthecorrelationofperceivedbeautywithagedictates

thatanystudyoftheimpactofbeautymustadjustforageifwebelievethatage

mightalso affecttheoutcome. Itisinteresting, though,to speculate whythese

differences arise. It might be that people’s inability to adjust mentally for age

when they rateothers’ looks is evolutionarily valuable. We are conditioned to

believethatyouthandbeautygotogether,sincethatbeliefencouragesmatingat

atimewhenfecundityisnearitsmaximum.

13

Thisevidenceonbeautyandagedoesnotcomparethesamepeopleovertheir

lifetimes, and no large-scale study has followed the same people’s looks over

largepartsoftheirlives.Smallerstudieshavedonethis,though,takingpictures

ofpeopleatanearlyageandaskingraterstoratethemandphotosofthesame

people taken much later in life. The ratings were very highly correlated. The

generalconclusionis,“Uglyducklingsgenerallyblossomintouglyducks.”

14

Whatisitaboutaperson’sfacethatleadsmostobserverstoviewitasgood-

looking? What characteristics of another person’s face cause most of us to

consider it plain or even homely? The answers to these questions are not

requiredforourpurposeshere:Solongaspeopleagreeaboutothers’looks,and

so long as we can adjust for any systematic differences across culture, age,

gender, race, or other characteristics in how looks are viewed, we can use

observers’commonagreementsaboutindividuals’lookstoanalyzetheimpacts

oflooksonoutcomesandevenonsuccessinavarietyofareas.

Althoughnoteconomic,thesequestionsarefascinating;andtheyhavebeen

studied by a number of social psychologists. The leading work, by my

University of Texas colleague Judith Langlois, has produced a number of

interestingresults,amongwhichare:(1)Agreementonwhatconstituteshuman

beauty, and especially human ugliness, is formed very early in life—probably

during infancy. (2) Symmetry is beauty—a symmetric face is considered

beautiful,whileincreasinglyasymmetricfacesareviewedasincreasinglyugly.

15

CANWEBECOMEMOREBEAUTIFUL?

The evidence makes it clear that people’s looks relative to those of others of

theiragedonotchangegreatlyovertheirlifetimes.Butwithcommonagreement

on looks, why don’t people alter them to meet the commonly agreed-upon

standardsofbeauty ofthesociety wheretheylive?Ifbeautycanpayoff,why

notbecomebeautiful?

Theprospectofbecomingbetter-lookingisendlesslyappealingtopeople.But

even fiction, such as the movie Face-Off with John Travolta, recognizes that

greatly changing one’s looks is exceedingly difficult. Procedures to remove

blemishes and wrinkles are done all the time, as is evidenced by actors,

actresses, and politicians who have “had a lot of work done,” using the

Hollywoodterminology.In2007,Americansreceivedover4.6millioninjections

of Botox, had 285,000nose-reshaping surgeries, and 241,000 eyelidsurgeries.

Allofthiswasgoodbusinessforplasticsurgeons,tothetuneof$12billionon

cosmeticplasticsurgery.

16

Citizensofotherwealthycountriesarelessweddedtotheseprocedures,but

they too devote substantial resources to them. In 2006, Britons devoted about

$800 million to cosmetic procedures, about one-third as much per capita as

Americans,butenoughtoleadtheEUonaper-capitabasis.Thiswasfourtimes

morethantheyhadspentin2001.ItaliansrankedsecondinEuropeinspending

oncosmeticsurgery,Francecamethird,closelyfollowedbyGermany.

17

While fictional beautification methods may convert “3” or even “1” people

into“5’s,”theirreal-worldcounterpartsdonotandcannotremovetheessential

asymmetries that detract from how their beauty is perceived by the rest of

humankind.Theeffortscanhelp,totheextentthatperceptionsofhumanbeauty

arebasedincharacteristicsotherthanthesymmetryoffacialfeatures.Weknow

thatthebeautyofyoungerpeopleisperceivedmorepositivelythanthatoftheir

elders,sothatattemptingtofindsurgicalfountainsofyouthwillhelp improve

howourbeautyisperceived.Nonetheless,thesechangesarelikelytobesmall.

Perhapsthepayoffstoplasticsurgeryaresimplynotgreatenoughtojustify

thespendingthatmightmakeonesubstantiallymorebeautiful.Perhapstheyare,

butthecostsoftheimprovement,bothindollartermsandinpainandsuffering,

are too large to get people to undergo the surgery. These possibilities are

suggestedbysomeresultsdescribingexamplesofplasticsurgeryinKorea.For

most people, the potential economic gains from the improvements in beauty

wereveryfarfromjustifyingeventhemonetarycostoftheprocedure,muchless

thepsychologicalcost—the“painandsuffering”—ofundergoinganysurgery.

18

If plastic surgery cannot convert usall tobeauties, orwe cannotafford the

costofsurgery,orwedon’twanttobearthepainofthesurgerythatwouldbe

requiredtoaccomplishthis,maybeasimplerapproachwouldwork:Buybetter

clothing,usemorecosmetics,getbettercoiffed,etc.Magazinesandnewspaper

columns are devoted to “dressing for success” and “beauty makeovers,”

includingrecommendationsoftheappropriateclothing,hairstyle,manicure,etc.

Doesthiskindofspendingreallywork?Canwemakeourselvesmorebeautiful

byspendingmoreonnon-surgicalmethodsofbeautyenhancement?

TheShanghaisurveycollectedinformationontheamountthateachwoman

spenteachmonthonclothing,cosmetics,andhaircare,aswellasonherlooks,

as rated by the interviewer. Comparing the woman who spent the average

amount on these items per month, to another who spent nothing, the average

woman’sspendingonlyraisedherlooksfrom3.31to3.36.Onemightthinkthat

thesewomencoulddobetterbyspendingstillmore;anditistruethatincreasing

spending to five times the average (over 20 percent of average household

income)wouldraisetheratingoftheaveragewoman’sbeautyto3.56.Butthe

datamakeitveryclearthattheextraeffectofthisspendingdiminishesthemore

onehasalreadyspent.

19

Many popular stories suggest that people believe that wardrobe, hairstyle,

cosmetics, and surgery will improve their economic outlook.

20

The evidence

indicates that this is simply wrong: in the Chinese study each dollar spent on

improvingbeautybroughtbackonlyfourcentsonaverage.Justasmuchofour

spending on health may not increase our longevity, but may let us enjoy life

more,sotooitmaymakesensetospendonplasticsurgeryandbetterclothes.

Thebestreasonforthiskindofspendingisthatitmakesyouhappier.Itisnota

goodinvestmentifyouseekonlythenarrowgoalofeconomicimprovement.

Somedaytechnologymayallowustoreachthepointwherewecanimprove

ourbeautyeasilyandwithoutgreatcost.Rightnow,though,wearesofaraway

from that point that for most of us the beauty that we have attained as young

adults is not going to be greatly altered, compared to the beauty of our

contemporaries,bynaturalchangesthatoccurasweage,norbyanysurgicalor

cosmeticeffortsthatweundertaketoimproveit.Barringdisfiguringaccidents,

wearebasicallystuckwithwhatnatureandperhapsearlynurturehavegivenus.

THESTAGEISSET

The array of evidence presented here provides the background for discussing

howaneconomicwayofthinkingabout beautymightproceed—howwhatwe

know about human perceptions of human beauty conditions the analysis of

beauty’seffects.Themainconsistentresultsare:

1. Most important of all, there is substantial agreement among observers

aboutwhatconstitutesfacialbeauty.Beautyisintheeyeofthebeholder,

but most beholders view beauty similarly. Some people are consistently

regarded as above-average or even beautiful, while others are generally

regardedasplainorevendownrighthomely.

2.Inmanystudies,morepeopleareratedasgood-thanasbad-looking.

3. Beauty is fleeting—and youth is beauty. Even when we are asked to

accountfor individuals’agesin judgingtheir looks,wejust cannotdo it.

Peopletendtorateyoungadultsasmoreattractivethanolderpeople.

4.Peoplewhoareviewedasrelativelygood-lookingwhenyoungtendtobe

ratedasrelativelygood-lookingwhenolder.

5. While looks can be altered by clothing, cosmetics, and other short-term

investments, the effects of these improvements are minor. Even plastic

surgerydoesn’tmakeahugedifference.Theoldadage,“Youcan’tmakea

silkpurseoutofasow’sear,”appliestohumanlooksaswellastoporcine

purses. Even with today’s technology and lower costs, we are generally

stuckwithwhatnaturehasgivenusinthewayoflooks.

6.Women’slooksareperceiveddifferentlyfrommen’s—observersaremore

likelytoratewomenasbeautifulorugly,andaremorelikelytodisagree

aboutwomen’slooks.

Taking all theseconsiderations together, our agreementon what constitutes

beauty allows sufficient scope for beauty to affect behavior in many facets of

economiclife.Becausepeopleagreeaboutothers’lookstoatleastsomeextent,

marketsforlabor,mates,credit,andnodoubtothermarkets,canbeaffectedin

ways that alter how participants in those markets behave and that help to

determinethebenefitsthattheyobtain.

PARTII

BeautyontheJob:

WhatandWhy

CHAPTER3

BeautyandtheWorker

THECENTRALQUESTIONS

Everybody assumes that better-looking people make more money. But why

shouldthatbe?Isiteventrue?Andifitistrue,howmuchmoredotheymake?

Putsimply,howmuchextradoesagood-lookingworkerearnthananaverage-

looking worker? How much less than an average-looking worker does a bad-

looking worker make? These sound like simple questions, but they aren’t.

Becausebeautymayberelatedtoothercharacteristicsthatworkerspossess,we

needtoseparateouttheeffectsofbeautyonincomefromthoseofotherthings

thatmayberelatedtobothbeautyandincome.Answerstothesequestionsare

the most widely available in the burgeoning literature in pulchronomics—the

economicsofbeauty.Wehaveaprettygoodfeeltodayforthegeneralsizesof

thebeautypremiumandtheuglinesspenalty.

Does beauty affect income differently for men and women? Does it affect

income differently among older workers than among younger workers? How

aboutbyraceorethnicity?WhileIconcentrateontheUnitedStatesthroughout

mostofthisbook,onewonderswhethertheimpactsofbeautyonincomesdiffer

betweentheUnitedStatesandothercountries.Isthereaspecial“hang-up”with

beauty in the American labor market that produces unusually large effects on

incomes compared to elsewhere? How have gains in income that result from

one’sbeautychangedovertime?Areweoutgrowingafixationonlooks,ordoes

theeffectoflooksinlabormarketsloomevenlarger?

HOWCANBEAUTYAFFECTEARNINGS?

Imagineaworldwithonlytwocompanies,eachwithasinglebosswhomakes

allthehiringdecisions.CallthebossesCathyandDeb.Theircompaniesmake

completely different products—they do not compete with each other in what

they sell; and each employs half of the workersin this imaginaryworld. Both

Cathy and Deb like to surround themselves with workers whom they view as

beautiful.Doingsomakesthemfeelbetterandenhancestheirwell-beingbeyond

thetremendousprofitstheywillearnfromtheirworkers’efforts.Alltheworkers

are equally productive—each has the same set of skills, each can help the

employerproduceasmuchasanyotherworkercan.Allworkersworkthesame

numberofhoursperyear.Halftheworkersareclonedfromoneparent,Al;the

otherhalfareclonedfromanotherparent,Bob.AllAlworkerslookalike,asdo

allBobworkers;butanAlworkerlooksdifferentfromaBobworker.

HowmuchwilleachAlworkerbepaid?HowmuchwilleachBobworkerbe

paid?WeknowthateachAlworkerwillearnthesameaseveryotherAlworker

—theyareidenticalinallrespects.ThesameistrueforeachoftheBobworkers

—theytooareidenticaltoeachother.TheonlyissueishowAlworkers’wages

willdifferfromBobworkers’wages.

Becausethey,likepeoplegenerally,sharecommonstandardsofbeauty,it’s

likely that Cathy and Deb think somewhat similarly about the looks of their

potential employees. What if both Cathy and Deb think that Al workers are

beautiful,whileBobworkersarenot?IfAlandBobworkerswerepaidthesame

wage,bothCathyandDebwouldwanttohirealltheAlworkers.Butthereare

onlyenoughAlworkersforoneofthem.Theonlywaythatcompetitionforthe

AlworkerscanassignthemtoCathyorDebisifthewagesofAlworkersare

biduptothepointwheretheirextrapayjustoffsetstheextrasatisfactionthatthe

“winning”employergetsfromemployingtheAlworkers.

Towinthe competition for the(good-looking)Al workers, Cathy mustpay

them a premium,just enough to outbid Deb. Her costs are higher than Deb’s,

who is stuck with the Bob workers who both Deb and she view as ugly. But

Cathy is just as happy about her employees as Deb, since her extra costs are

offsetbythe extra satisfactionshe gets fromemployingthe Al workerswhom

Debandshebothviewasbeautiful.Withacommon standardofbeauty,labor

markets establish premium pay for the good-looking workers—or, viewed in

reverse, penalty pay for the ugly workers—based on the extent to which

employersvaluelooks.InthiscasethepremiumistheamountthatCathyhasto

paytoovercomeDeb’sdesireforthegood-lookingAlworkers.

ThisexampleassumedthatCathy’sandDeb’spreferencesfortheirworkers’

beautydeterminewhatwageswouldbe.Whatif,though,CathyandDebdon’t

reallycareabouttheirworkers’looks,buttheircustomerscareaboutthelooksof

theworkerswhomakethegoodstheybuy,ormorerealistically,aboutthelooks

of the workers who are selling to them? If both Cathy’s and Deb’s customers

prefer Al-type workers, Al-type workers will receive higher wages than Bob-

typeworkers.Theoutcomesarethesame,whetheritisCathy’sandDeb’sown

preferences that determine the effect of looks on wages, or whether their

behaviorjustexpressestheircustomers’preferences.

Whose preferences generate premium pay for beauty, and penalties for

ugliness, can’t be determined just by showing the existence and size of those

differencesinearnings—itrequiresadeeperinvestigationofunderlyingcauses.

Wemustfirstseewhetherandbyhowmuchbeautyisrewarded,aswedointhis

chapter. We need to discover how it affects people’s choices of what work to

undertake;andweneedtoseehowcompanies’salesandprofitsrelatetotheir

employees’looks.

HOWMUCHMOREDOGOOD-LOOKINGPEOPLE

MAKE?

To begin answering these questions, take the most important: To what extent

doesbeautyaffecttheearningsofthetypicalworker?Onitsfacethisseemsto

be a simple task: Find a large group of individuals, randomly chosen from a

country’s population; get measures of their looks, by one of the methods we

havediscussed;obtaininformationontheirearnings;andcomparetheirearnings

totheirlooks.

ThisisnotsoeasytodofortheUnitedStatesasonemightthinkorhope—

the most recent nationally random data that provide this information are from

surveys collected in the 1970s—the data underlying table 2.1. Regrettably, no

nationally representative set of data since the 1970s contains information on

earnings and also ratings of the respondents’ beauty. This means that these

effects are best described as what were the effects of beauty on earnings. But

using these data we can get an initial picture of how beauty and earnings are

relatedinthegeneralpopulation.

Usingtheselargerandomsamplesofwomenandmen,wecancomparetheir

earnings to the ratings of their looks. Compared to the average group (people

ratedas3onthe5to1scale),below-averagelookingwomen(rated2or1onthe

scale) earn 3 percent less, while below-average looking men earn 22 percent

less.Above-averagelookingwomen(rated 4 or 5 on the scale) earn 4 percent

morethantheaverage-looking,whileabove-averagelookingmenearn3percent

more.Thereisapremiumforgoodlooks,apenaltyforbadlooks.Exceptforthe

penaltyforthe11percentofmenwhoselooksareratedasbelow-average,these

differences in earnings are not large; but they are in the directions that you

wouldexpect.

These simple differences are interesting; but are they genuine, or do they

merely reflect the strong possibility that beauty and other things that increase

one’searningsarerelated?Thenumberof“otherthings”ispotentiallyhuge;but

a thorough approach would take anything that has repeatedly been shown to

affectearnings,andwouldthenadjustforitsimpactsinordertoisolatetheeffect

ofbeautyonearnings.Theseotherfactorsinclude:

• Education (increasing earnings)—what if better-looking people are better

educated?

•Age(increasingearningsuptosomepoint,perhapstothemid-fiftiesfora

typicalworker,thenreducingearnings)—weknowthatageandbeautyare

related

•Health(healthierpeopleearnmore)—beautymayberelatedtohealth

•Unionmembership(increasingearnings)

•Maritalstatus(positiveeffectsamongmen,negativeeffectsamongwomen)

—beautymayberelatedtowhetheryouaremarriedornot

•Race/ethnicity(minoritiesearnlessthannon-Hispanicwhites)

•Sizeofcity(higherearningsinbiggercitiesandinmetropolitanasopposed

tonon-metropolitanandruralareas)

•Region(higherintheEastthanintheSouth)

•Nativity(immigrantsearnlessthannatives)

•Familybackground(loweramongpeoplewhoseparentswereimmigrants)

•Sizeofcompany(higherinbigfirms)orplant(higherinlargerplants)

•Yearswiththecompany(increasingearningsuntillateinaperson’stenure

withthecompany)

Numerousstudieshaveshownthateachofthesefactorsaffectsearnings.Since

mostorevenallofthemmightdiffersystematicallywithanindividual’slooks,

toisolatetheeffectoflooksonearningsweneedtoadjustearningsusingdataon

asmanyofthemaswecan.

Table3.1showstheaverageimpactsofbeautycombiningdatafromthetwo

samplesofAmericansinthe1970s.Thepenaltiesforbelow-averagelooks,and

the premia for above-average looks, are based on statistical analyses that

adjustedearningsformostoftheseotherfactorsinordertoisolatetheeffectof

differences in beauty. An asterisk (*) denotes that the impact is statistically

meaningful—thatwecanbefairlysurethatlookshavesomeeffectonearnings.

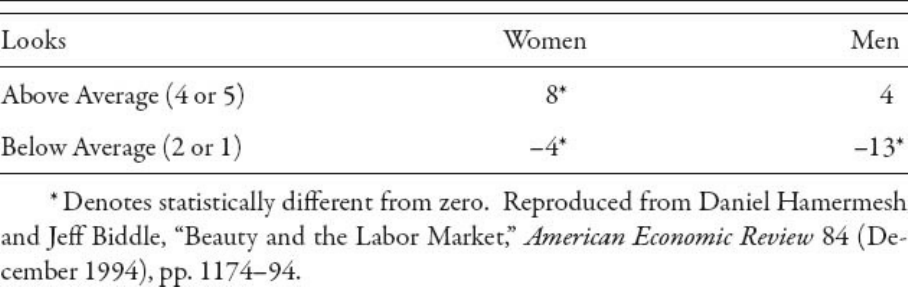

TABLE3.1

PercentageImpactsofLooksonEarnings,U.S.,1970s(comparedtoaverage-lookingworkers,rated3),

AdjustedforManyOtherDeterminantsofEarnings

Notethatthesenumbersareinthesamedirectionsasthenumbersthatdidnot

accountforalltheotherdeterminantsofearnings.Theydochange—theseother

determinants of earnings do matter; but the basic conclusion, that there is a

penaltytoearningsforbadlooksandpremiumpayforgoodlooks,isunaltered.

Ifasked,“WhatistheoveralleffectoflooksonearningsintheU.S.?”thebest

answer, based on table 3.1, is thatthe bottom 15 percent of women by looks,

those rated as below-average (2 or 1), received 4 percent lower pay than

average-looking women. The top one-third of women by looks, those ratedas

above-average(4or5),received8percentmorethanaverage-lookers.Formen,

thecomparablefiguresarea13percentpenaltyanda4percentpremium.

There is nothing written in stone about these numbers. No doubt, if other

nationally representative data were available, the estimates of these effects

woulddiffer.Butwecanbefairlysurethattheeffectsofbeautyonearningsare

intheballparkofthefiguresintable3.1.

Thesenumbersmeanlittlebythemselveswithoutcomparisonstotheeffects

ofotherdeterminantsofdifferencesinearnings.Howdoesthe17percentexcess

of good-looking men’s earnings over those of bad-looking men’s (13 percent

penaltyplus 4percent premium)comparetotheeffects ofdifferences inother

characteristicsonmen’searnings?Howdoesthe12percentshortfallofplainor

homelywomen’searningsfromabove-averageorbeautifulwomen’s(4percent

penaltyplus8percentpremium)comparetoothereffectsonwomen’searnings?

Byfarthemostthoroughlyexamineddeterminantofearningsiseducation.A

good estimate for the United States today is that each additional year of

schooling raises the earnings of otherwise identical workers by around 10

percent.

1

This effect is a bit more than that of women’s good looks; and it

impliesthatmen’sgoodlookshaveanimpactontheirearningsatleastaslarge

asanadditionalone-and-a-halfyearsofschool.

Amongtheotherfactorsthataffectearningsareworkexperienceandwhether

aworkplaceisunionized.Foraforty-year-oldmantheimpactofgoodlookson

earningsisaboutthesameasthatofanadditionalfiveyearsofworkexperience,

and also about the same as that of working in a unionized workplace.

2

The

effectsofbeautyonearningsarenotimmense,buttheyarecertainlysubstantial.

Whenviewedinthecontextofanentireworkinglife,theyseemevenlarger.

In 2010, the average worker earned about $20 per hour. Averaging male and

female workers, someone employed 2,000 hours per year over a work life of

fortyyearswouldearn$1.60million.Butwithbelow-averagelookstheworker

would earn only $1.46 million, while with above-average looks, lifetime

earningswouldbe$1.69million.

3

A3or4percentpremiumforgood-looking

workersdoesn’tseemthatbig;butplacedintoa lifelongframework,$230,000

extra earnings for being good-looking instead of bad-looking no longer seems

small. Comparing the bad-looking to the average-looking worker the effect is

smaller—“only”$140,000overalifetime—butstillquitelarge.Comparingthe

average-lookingtothe above-averagelooking worker the effect is smallerstill

—“only”$90,000overalifetime—butstillsubstantial.

Alloftheseeffectsrefertoaverages:Theytellusthatatypicalgood-looking

malewillearn4percentmorethanthetypicalaverage-lookingmale,andthata

typicalbelow-average-lookingwomanwillearn4percentlessthanthetypical

average-lookingwoman.Thisdoesnotmeanthateachgood-lookingmalewill

earn4percentmorethaneachaverage-lookingmale.Wehaveseenthatthereare

manyotherfactorsthataffectearnings,andthesewilldifferbetweenmenwhose

looks are viewed as the same. Even more important, there is tremendous

randomnessinearningsthatisunrelatedtolooksoranyoftheotherthingswe

canmeasureandthataffectearnings.Amongarandomlychosengroupofmale

workers,orfemaleworkers,atleasthalfofthedifferencesinearningsaredueto

things that we can’t measure; and among those that we can measure, looks

accountforonlyasmallfractionofthedifferences.Looksdomatteralot;but

otherthingsmattermuchmore.

Becausesofewpeopleareclassifiedasbeautiful(rated5)orhomely(rated

1),itisnotpossibletodistinguishstatisticallytheimpactofbeingbeautifulfrom

being above-average (rated 4), or of being homely from being plain (rated 2).

Despite that, and even though the differences are not statistically meaningful,

additional analyses of these same data show that the beautiful man or woman

earns more than the above-average, and the homely earn less than the plain.

Extreme looks are uncommon, but they generally produce extreme effects on

successinlabormarkets.

Theword“generally”iskeyhere.Manypeoplebelievethata“bimboeffect”

exists—that extremely good-looking women are somehow penalized in labor

markets. In my own research I have found only one bit of evidence for this

effect:Inastudyofattorneys,theverybest-lookingfemaleattorneyswereless

likely to achieve partnership before their fifth year after graduation from law

schoolthanaverage-lookingwomenattorneys.

4

Liketheirbrethren,though,their

extreme beauty did give them higher earnings. There may be bimbo effects in

someinstances,buttheyareprettyrare.

There have been many efforts to measure the effect of beauty on earnings

usingdataonindividualsinothercountries.Interestinthetopicishardlylimited

to the United States. All of these have tried to adjust for many of the same

determinantsofearningsthatIhaveusedtoisolatetheeffectsofbeautyinthe

United States. The availability of information on all these measures differs

across countries and sets of data, so that the studies are neither entirely

comparabletothosefromtheUnitedStatesnortoeachother.Theyarealsonot

comparable for another crucial reason: We saw that there are international

differences in the willingness of raters of beauty to classify people as being

below-average in looks. Americans are remarkably willing to make these

relatively harsh judgments when they interview respondents or evaluate their

photographs.Thistoomightcausetheestimatedeffectsofbeautyelsewhereto

differfromthoseintheUnitedStates.

IhavefoundstudiesforAustralia;Canada;Shanghai,China;Korea;andthe

United Kingdom.

5

They show that in other countries too there are significant

negative impacts on earnings of being below-average in looks. In most cases

therearealsopositiveeffectsofbeingabove-average.Nogeneralizationsabout

cross-countrydifferencesintheeffectsof beautyonearnings arepossible.But

the negative effects of being below-average in looks typically exceed the

positiveeffects of being above-average.One explanation is thatso few people

are classified as below-average in these studies that being called “below-

average”indicatesseriouslydeficientlooks.

Althoughmakingcomparisonsoftheseeffectstothoseshownintable3.1for

theUnitedStatesisdifficult,theeffectsofbeautyinothercountriesdonotseem

that different from those in the United States. Theeffects in the UnitedStates

maybe somewhatlarger, butnothugely so.As intheUnitedStates,so tooin

mostofthesecountries,goodlooksarerewarded,andbadlooksarepenalized,

evenafteraccountingforalargevarietyofotherfactorsthataffectearnings.

TheAmericandataclearlyaresomewhatoutdated.Withcurrentdatawould

wefindthesameeffects?PerhapsAmericansarenolongersoconcernedabout

looks when they react to co-workers, employees, or people selling them a

product or a service. Perhaps the opposite has occurred, so that, given the

preoccupationwithlooksintheAmericanmediatoday,withtheriseofcelebrity

magazines,andwiththegrowthofthesocialnetworkingInternetsite,Facebook,

theeffectsareevengreaterthantheywereinthe1970s.

The absence of data makes it impossible to obtain updated estimates of the

impactofbeautyonearningsforthegeneralpopulation,butbeautyratingsfrom

anationalsurveyofyoungadultsintheearly2000shavebeenusedtoexamine

this question. Looking only at male high school graduates, going from

“unattractive” (rating of 2 on the commonly used 5 to 1 scale) to “very

attractive”(ratingof4)generatedanincreaseinearningsofcloseto11percent

among young women, and 17 percent among young men.

6

These effects are

remarkablyclosetothoseintable3.1,offeringahintthatperhapstheeffectsof

beautyonearningsremainsubstantialandsubstantiallyunchanged.

Withoutanyadditional evidence on thegeneralpopulation,there is no sure

way of deciding this issue. Either possibility may be correct. My best guess,

though, absent any reason to believe that labor markets have changed in one

directionortheother,isthattheeffectsofbeautytodayarenotmuchdifferent

fromthosethatprevailedintheUnitedStatesinthe1970s.

Theeffectsoflooksonearningsmightwellchangeoverthebusinesscycle,

as the economy moves between recession and full employment. From the

employer’s side of labor markets, having more unemployed workers available

allows greater choice about workers’ characteristics. In bad times, Cathy and

Deb might have more scope to indulge their desires for beautiful workers. In

discussingraceinlabormarkets,wegenerallybelievethatunemploymentgives

employers more latitude to discriminate.

7

If looks are treated the same way,

beautymighthelpagood-lookingworkermoreduringarecession,whenthereis

morecompetitionfromotherjobseekers.Itseffectswillbelesswhenworkers

arescarceandemployerscannotaffordtobesochoosy.

No study has looked at this question generally. But among law school

graduateswhoenteredthelabormarketwhenjobsfornewattorneyswerevery

plentiful,theimpactofdifferencesinlooksontheirearningswassmall.Among

attorneyswhosoughtworkwhenjobswerelessreadilyavailable,earningswere

morestronglyaffectedbydifferencesintheirbeauty.Thissinglecomparisonis

not definitive, but itdoes suggestthat the effects of beautyon earnings might

riseinrecessions.

ISBEAUTYTHEREALCAUSE?

Therearealotofotherfactorsthatmightaffectearningsandthatcouldnotbe

accounted for in most of these studies. One concern is that beauty may just

reflect self-esteem. Perhaps people’s self-confidence manifests itself in their

behavior,sothattheirlooksareratedmorehighly,andtheirself-esteemmakes

themmoredesirableandhigher-paidemployees.TheCanadianstudyincludeda

setofquestionsthatpsychologistsusetomeasureself-esteem.Self-esteemand

looks were positively related—but the correlations in these data were quite

weak:Thetypicalgood-lookingpersonwasonlyslightlymorelikelytoexpress

substantialself-esteemthan the typical bad-looking person. Adjusting earnings

for the effects of self-esteem, workers who expressed greater self-esteem did