An Introduction to the Grammar of English

Revised edition

An Introduction

to the Grammar of English

Revised edition

Elly van Gelderen

Arizona State University

John Benjamins Publishing Company

Amsterdam / Philadelphia

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gelderen, Elly van.

An introduction to the grammar of English / Elly van Gelderen. -- Rev. ed.

p. cm.

Rev. ed: .

Includes bibliographical references and index.

. English language--Grammar. . English language--Grammar, Historical. . English

language--Social aspects. . English language--Syntax. I. Title.

PE.G

.--dc

(; alk. paper) / (; alk. paper)

()

© – John Benjamins B.V.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, or any

other means, without written permission from the publisher.

John Benjamins Publishing Co. · P.O. Box · Amsterdam · e Netherlands

John Benjamins North America · P.O. Box · Philadelphia - ·

e paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of

American National Standard for Information Sciences – Permanence of

Paper for Printed Library Materials, z39.48-1984.

8

TM

Table of contents

Foreword xi

Preface to the second edition xv

Abbreviations xvii

List of gures xix

List of tables xxi

chapter 1

Introduction 1

1.

Examples of linguistic knowledge 1

1.1

Sounds and words 1

1.2

Syntactic structure 2

2.

How do we know so much? 5

3.

Examples of social or non-linguistic knowledge 6

4.

Conclusion 8

Exercises 9

Class discussion 9

Keys to the exercises 10

Special topic: Split innitive 10

chapter 2

Categories 12

1.

Lexical categories 12

1.1

Nouns (N) and Verbs (V) 13

1.2

Adjectives (Adj) and Adverbs (Adv) 15

1.3

Prepositions (P) 18

2.

Grammatical categories 19

2.1

Determiner (D) 19

2.2

Auxiliary (Aux) 21

2.3

Coordinator (C) and Complementizer (C) 21

3.

Pronouns 23

4.

What new words and loanwords tell us! 24

5.

Conclusion 25

Exercises 27

Class discussion 29

Keys to the exercises 30

Special topic: Adverb and Adjective 32

vi An Introduction to the Grammar of English

chapter 3

Phrases 35

1.

e noun phrase (NP) 36

2.

e adjective phrase, adverb phrase, verb phrase

and prepositional phrase 39

2.1

e adjective phrase (AdjP) and adverb phrase (AdvP) 39

2.2

e verb phrase (VP) 40

2.3

e prepositional phrase (PP) 41

3.

Phrases in the sentence 42

4.

Coordination of phrases and apposition 43

5.

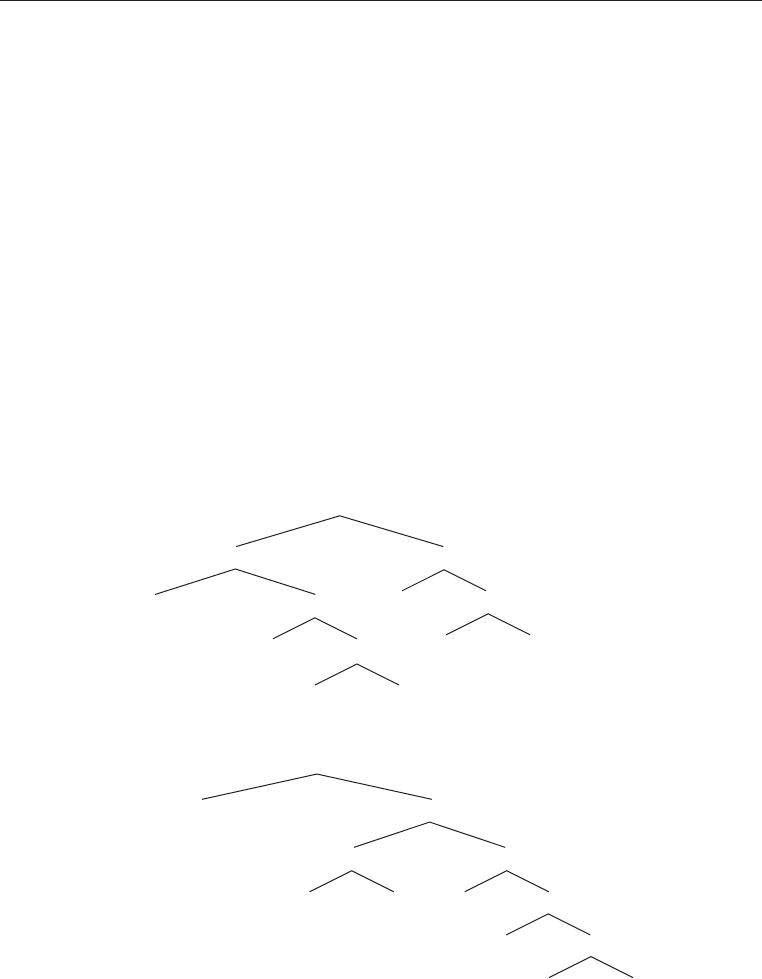

Finding phrases and building trees 45

5.1

Finding the phrase 45

5.2

Building trees 46

6.

Conclusion 49

Exercises 50

Class discussion 51

Keys to the exercises 52

Special topic: Negative concord 56

Review of Chapters 1–3 59

Exercises relevant to these Chapters: 60

Class discussion 60

Keys to the exercises 61

Example of an exam/quiz covering Chapters 1 to 3 63

Keys to the exam/quiz 63

chapter 4

Functions in the sentence 65

1.

Subject and predicate 65

2.

Complements 68

2.1

Direct and indirect object 68

2.2

Subject and object predicate 70

3.

Verbs and functions 72

4.

Trees for all verb types 74

5.

Light verbs (optional) 76

6.

Conclusion 77

Exercises 78

Class discussion 80

Keys to the exercises 80

Special topic: Case and agreement 83

Table of contents vii

chapter 5

More functions, of prepositions and particles 86

1.

Adverbials 86

2.

Prepositional verbs 90

3.

Phrasal verbs 90

4.

Phrasal prepositional verbs (optional) 93

5.

Objects and adverbials 93

6.

Conclusion 96

Exercises 97

Class discussion 99

Keys to the exercises 100

Special topic: e passive and ‘dummies’ 102

chapter 6

e structure of the verb group (VGP) in the VP 105

1.

Auxiliary verbs 105

2.

e ve types of auxiliaries in English 107

2.1

Modals 107

2.2 Perfect have

(pf) 109

2.3 Progressive be

(progr) 110

2.4 Passive be

(pass) 111

2.5 e ‘dummy’ do

112

3.

Auxiliaries,‘ax hop’, and the verbgroup (VGP) 113

4.

Finiteness 114

5.

Relating the terms for verbs (optional) 116

6.

Conclusion 118

Exercises 120

Class discussion 121

Keys to the exercises 122

Special topic: Reduction of have

and the shape of participles 122

Review of chapters 4–6 124

Examples of midterm exams covering Chapters 4 to 6 127

Example 1 127

Example 2 127

Example 3 128

Key to example 1 129

Key to example 2 130

Key to example 3 131

viii An Introduction to the Grammar of English

chapter 7

Finite clauses: Embedded and coordinated 132

1.

Sentences and clauses 133

2.

e functions of clauses 134

3.

e structure of the embedded clause: e Complementizer Phrase (CP) 135

4.

Coordinate sentences: e Coordinator Phrase (CP)? 138

5.

Terminological labyrinth and conclusion 139

Exercises 141

Class discussion 142

Keys to the exercises 143

Special topic: Preposition or complementizer: e ‘preposition’ like

146

chapter 8

Non-finite clauses 149

1.

Non-nite clauses 149

2.

e functions of non-nites 151

3.

e structure: CP 152

4.

Coordinating non-nites 154

5.

Conclusion 155

Exercises 156

Class discussion 157

Keys to the exercises 159

Special topic: Dangling participles and gerunds 161

Review of Chapters 7 and 8 164

Exercises 165

Keys to the exercises 165

Sample quiz/exam, covering Chapters 7 and 8 166

Keys to the quiz/exam 167

chapter 9

e structure of the PP, AdjP, AdvP, and NP 169

1.

e structure of the PP, AdjP, and AdvP and the functions inside 170

2.

e structure of the NP and functions inside 172

3.

Arguments for distinguishing complements from modiers (optional) 176

3.1

Complement and modier follow the head N 176

3.2

Complement and modier precede the head N 177

4.

Conclusion 179

Exercises 181

Table of contents ix

Class discussion 182

Keys to the exercises 183

Special topic: Pronoun resolution 188

chapter 10

Clauses as parts of NPs and AdjPs 189

1.

Relative clauses (RC) 189

2.

Inside the NP: Relative and complement clauses 190

2.1

Relatives 190

2.2

Complement clauses 191

2.3

Reduced relative clauses 192

3.

NPs as compared to AdjPs, AdvPs, and PPs 193

4.

More on RCs 194

5.

e structure of modiers and complements (optional) 195

6.

Conclusion 198

Exercises 199

Class discussion 200

Keys to the exercises 200

Special topic: Relative choice and preposition stranding 203

chapter 11

Special sentences 205

1.

Questions/Interrogatives: e CP 205

2.

Exclamations 207

3.

Topicalization, passive, cle, and pseudo-cle 208

4.

Conclusion 209

Exercises 210

Keys to the exercises 210

Special topic: Comma punctuation 211

Review of Chapters 9–11 214

Home work 1, on Chapter 1 and Special topics 215

Home work 2, covering Chapters 2 –11 215

Home work 3, or take-home exam, covering Chapters 7–11 216

Examples of Final Exams 217

Example 1 217

Example 2 219

Example 3 220

Glossary 222

References 229

Index 230

x An Introduction to the Grammar of English

Foreword

To the student:

You don’t have to read long books or novels in this course – no Das Kapital, Phenom-

enology of Spirit, Middlemarch, or War and Peace. ere isn’t too much memorization

either. It should be enough if you become familiar with the keywords at the end of

each chapter. Use the glossary, if it is helpful, but don’t overemphasize the importance

of terminology.

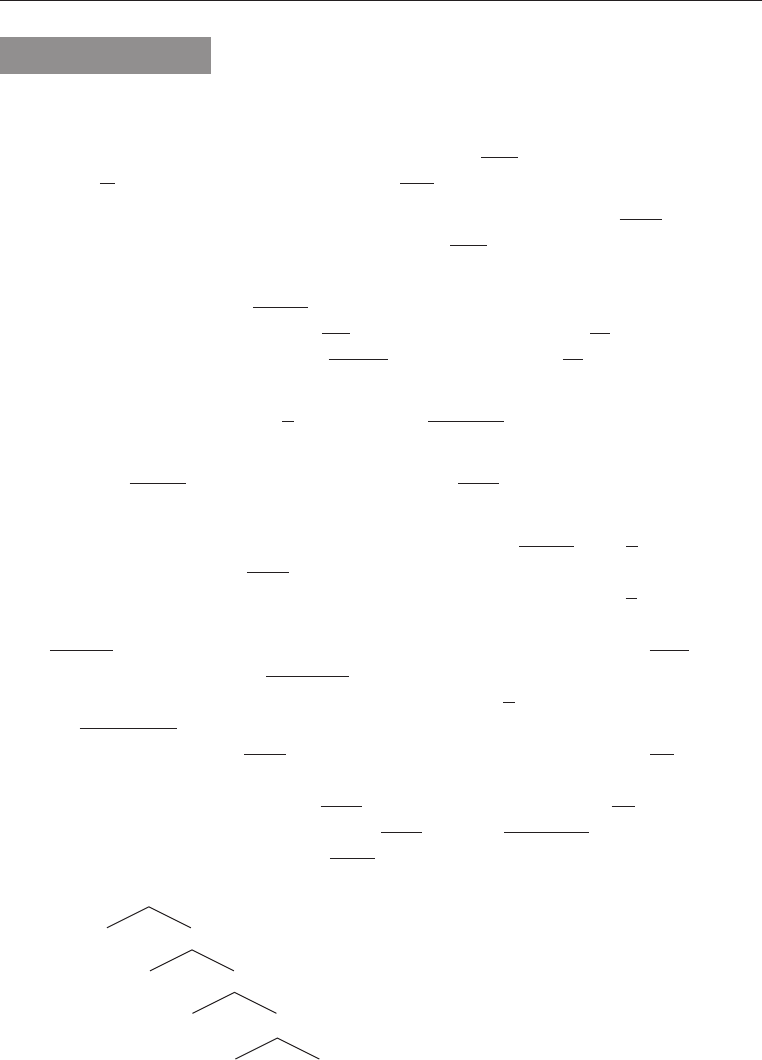

e focus is on arguments, exercises, and tree drawing. You need to practice from

the rst week on, however, and you may also have to read a chapter more than once.

Pay attention to the tables and gures; they oen summarize parts of the text. e

course is not particularly dicult but, once you get lost, go for help!

e book is divided in four parts (Chapters 1 to 3, Chapters 4 to 6, Chapters 7 and 8,

and Chapters 9 to 11), with review sections aer each. Chapter 1 is the introduction;

skip the ‘about the original edition’ and ‘preface to the second edition’, if you want.

About the original edition

e philosophy behind the book hasn’t changed in the second edition so I have

adapted the preface to the rst edition here and have then added things special to the

second edition.

is grammar is in the tradition of the Quirk family of grammars, such as the

work of Huddleston, Burton-Roberts, Aarts & Wekker, Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech,

and Svartvik whose work in turn is based on a long tradition of grammarians such

as Jespersen, Kruisinga, Poutsma, and Zandvoort.

1

However, it also uses the insights

from generative grammar.

While following the traditional distinction between function (subject, object, etc.)

and realization (NP, VP, etc), the book focuses on structure and makes the function

derivative, as in more generative work. e book’s focus on structure can be seen in the

treatment of the VP as consisting of the verb and its complements. Abstract discussions,

such as what a constituent is, are largely avoided (in fact, the term constituent is since it

1. ese are all well-known references, so I have refrained from listing them in the references.

xii An Introduction to the Grammar of English

is a stumbling block in my experience), and the structure of the NP and AP is brought

in line with that of the VP: NPs and APs have complements as well as modiers.

A clear distinction is made between lexical and functional (here called grammati-

cal) categories. Lexical categories project to phrases and these phrases have functions

at sentence level (subject, predicate, and object). In this book, the functional categories

determiner, auxiliary, and (phrasal) coordinator do not project to phrases and have

no function at sentence level. ey function exclusively inside a phrase or connect

phrases. Hence, determiner, auxiliary, and coordinator express realization as well as

function. Complementizers and those coordinators that introduce clauses do head the

CP in this second edition. e reason that I have changed the S’ from the rst edition

into a CP is two-fold. (a) e S’ is confusing since it is not an intermediate projection

and (b) the CP is more in line with current syntactical frameworks. e CP can func-

tion as subject, object, and adverbial. In a generative syntax book, I would of course

have all functional categories project to phrases such as DP, QP, and TP, but for an

introductory grammar book, I think having the lexical categories (and the C) project

is a better choice. e distinction between lexical and functional category is of course

not always clearcut, e.g. adverbs, pronouns, and some prepositions are in between. I

do bring this up.

On occasion, I do not give a denitive solution to a problem because there isn’t

one. is lack of explanation can be caused either because an analysis remains contro-

versial, as in the case of ditransitive verbs and coordinates, or because of the continual

changes taking place in English (or any other language for that matter). Instead of giv-

ing one solution, I discuss some options. I have found that students become frustrated

if, for instance, they can reasonably argue that a verb is prepositional in contexts where

‘the book says’ it is an intransitive verb. e emphasis in this book is on the argumenta-

tion, and not on presenting ‘the’ solution. e chapter where I have been quite conser-

vative in my analysis is Chapter 6. e reason is that to provide the argumentation for

a non-at structure involves theta-theory, quantier-oat, and the introduction of the

TP and other functional categories. is leads too far.

e book starts with a chapter on intuitive linguistic knowledge and provides

an explanation for it based on Universal Grammar. At the end of each chapter, there

is a discussion of prescriptive rules. In my experience, students want to know what

the prescriptive rule is. Strangely enough, they don’t want the instructor to tell them

that, linguistically speaking, there is nothing wrong with splitting an innitive or

using like as a complementizer. ey want to (and should) know the rule. I have not

integrated the topics in the chapters since I want to keep descriptive and prescriptive

rules separate although that is sometimes hard. e topics are added to give a avor

for the kinds of prescriptive rules around and, obviously, cannot cover all traditional

usage questions.

e chapters in this book cover ‘standard’ material: categories, phrases, functions,

and embedded sentences. ere are a few sections that I have labeled optional, since,

depending on the course, they may be too much or too complex. e last chapter

could either be skipped or expanded upon. It should be possible to cover all chapters

in one semester. e students I have in mind (because of my own experience) are

English, Humanities, Philosophy, and Education majors as well as others taking an

upper level grammar course in an English department at a university. I am assuming

students using this book know basic ‘grammar’, for instance, the past tense of go, and

the comparative of good. Students who do not have that knowledge should be encour-

aged to consult a work such as O’Dwyer (2000).

Even though I know there is a danger in giving one answer where more than one

is sometimes possible, I have provided answers to the exercises. It is done to avoid

having to go over all exercises in class. I hope this makes it possible to concentrate on

those exercises that are interesting or challenging.

I would like to thank my students in earlier grammar courses whose frustration

with some of the inconsistencies in other books has inspired the current work. I am

sure this is not the rst work so begun. Many thanks also to Johanna Wood for much

helpful discussion that made me rethink fundamental questions and for suggesting

the special topics, to Harry Bracken for great comments and encouragement, to

Viktorija Todorovska for major editorial comments to the rst edition, to Tom Stroik

for supportive suggestions, to Barbara Fennell for detailed comments and insightful

clarications, and to Anke de Looper of John Benjamins for her insights on the rst

edition. For help and suggestions with the (originally planned) e-text as well as the

paper version, I am very grateful to Lut Hussein, Je Parker, Laura Parsons, and to

Susan Miller.

Foreword xiii

Preface to the second edition

It was time for an updated version of A Grammar of English. Some of the example

sentences read as if they were 10 years old and they are. us, Bill Clinton hasn’t been

the US president for a long time and Benazir Bhutto and Yasser Arafat are no longer

alive. It is also so much more accepted to use corpus sentences, and these examples

may speak more to the users. To keep the text clean of references, I give very basic

references, e.g. “CBS 60 Minutes”, and not always the exact date. It is now so easy to

nd those references that I think they aren’t needed. Many contemporary example

sentences come from Mark Davies’ Corpus of Contemporary American English and the

British National Corpus; the older ones from the Oxford English Dictionary or from

well-known plays.

I have updated the cartoons, added texts to be analyzed, rearranged and added to

the Special Topics, and provided more gures and tables. ere is also a website that

lists relevant links, repeats practice texts from this book for analysis, and contains

some resources: http://www.public.asu.edu/~gelderen/grammar.htm. I have deleted

the ‘Further Reading’ section since it was useless: too much detail on the one hand

and then very general references to introductory textbooks on the other hand. I think

the students who would use this section are smart enough to gure out other refer-

ences for themselves.

Due to a computer error that changed N′ and V′ etc into N and V (aer the second

page proofs had been corrected), the rst edition of this book had to be physically

destroyed and what ended up the rst edition in 2002 was actually a reprint. ere

were a few typos that survived this process. I hope that these are corrected and that

not too many new ones have been created.

I am very happy that the rst edition has been useful in a number of dier-

ent settings and places, e.g. in Puerto Rico, Norway, Turkey, Spain, Macedonia, e

Netherlands, the US, and Canada. I have used it myself with a lot of satisfaction, and

would like to thank many of my students in ENG 314 at Arizona State University. e

areas that I personally did not like in the rst edition are the at auxiliary verb struc-

tures in Chapter 6 and the S′ (and S) in Chapter 7. As mentioned, I have only changed

the S′ to CP, but haven’t introduced a DP, TP, or an expanded TP because this isn’t

appropriate for the audience. I have eliminated traces and use what looks like a ‘copy’

or sometimes the strike-through font. In Chapter 6, I have also introduced timelines

for tense and aspect since students oen ask about the names of tenses.

I would like to thank some of the same people as I did for the rst edition, in

particular Johanna Wood, Harry Bracken, and Laura Parsons. For comments in book

xvi An Introduction to the Grammar of English

reviews and beyond, I would like to thank Anja Wanner, Carsten Breul, Christoph

Schubert, and Nina Rojina. I am especially grateful to Mariana Bachtchevanova,

Eleni Buzarovska, Lynn Sims, James Berry, Amy Shinabarger, James Dennis, Wim

van der Wur, and Richard Young for detailed comments aer teaching with the

book, and also to Terje Lohndal. anks to Alyssa Bachman for providing a student

perspective and helping me add to sections that were less clear. Continued thanks to

Kees Vaes and Martine van Marsbergen.

Elly van Gelderen

Apache Junction, Arizona

November 2009

Abbreviations

Adj Adjective N′ N-bar, intermediate category

AdjP Adjective Phrase neg negative

Adv Adverb NP Noun Phrase

Adv-ial Adverbial ObjPr Object Predicate

AdvP Adverb Phrase OED Oxford English Dictionary

AUX Auxiliary P Preposition

BNC British National Corpus pass passive auxiliary

BrE British English pf perfect auxiliary

C Complementizer or PO Prepositional Object

Coordinator PP Prepositional Phrase

CP Complementizer Phrase Pre-D Pre-determiner

(or Coordinator Phrase) Pred Predicate

COCA Corpus of Contemporary prog progressive auxiliary

American Pron pronoun

D Determiner RC Relative Clause

(D)Adv Degree Adverb S Sentence (or Speech on time line)

DO Direct Object SC Small Clause

E Event time SU Subject

e.g. ‘for example’ SuPr Subject Predicate

i.e. ‘namely’ V Verb

inf innitive marker to V′ V-bar, intermediate category

IO Indirect Object VGP Verb group

N Noun VP Verb Phrase

? Questionable sentence.

* Ungrammatical sentence.

^ May occur more than one.

List of gures

Figure 1.1 Structural Ambiguity 3

Figure 1.2 How to use ‘dude’! 7

Figure 2.1 Connecting sentences 22

Figure 2.2 Gently into that … 28

Figure 3.1 From inside or into? 52

Figure 3.2 Multiple Negation 57

Figure 4.1 A schema of the functions of NPs, VPs, and AdjPs 77

Figure 4.2 Lie ahead 79

Figure 4.3 Who or whom? 84

Figure 5.1 Adverbials 89

Figure 5.2 More Phrasal verbs 92

Figure 5.3 e functions of PPs and AdvPs 96

Figure 5.4 Glasses 98

Figure 5.5 Put o until aer 99

Figure 5.6 Back up over 100

Figure 6.1 Timelines for tense and aspect 110

Figure 6.2 ree progressives 111

Figure 6.3 I think not 113

Figure 6.4 Drawed and drew 117

Figure 6.5 Timelines for tense and aspect (nal version) 121

Figure 7.1 A pony 133

Figure 7.2 Quotative ‘like’ 148

Figure 8.1 Embedded sentences 157

List of tables

Table 1.1 Alice’s Ambiguities 3

Table 2.1 Some dierences between N(oun) and V(erb) 14

Table 2.2 Dierences between adjectives and adverbs 18

Table 2.3 Some prepositions in English 19

Table 2.4 Determiners 21

Table 2.5 A few complementizers 22

Table 2.6 e categories in English 26

Table 3.1 Finding a phrase 45

Table 4.1 Subject tests 66

Table 4.2 Verbs with direct and indirect objects 70

Table 4.3 Examples of verbs with subject predicates 71

Table 4.4 Verbs with direct objects and object predicates 71

Table 4.5 Examples of the verb classes so far with their complements 74

Table 5.1 Examples of phrasal verbs 93

Table 5.2 Dierences among objects, su/obj predicates,

and adverbials 93

Table 5.3 Verb types and their complements 96

Table 6.1 Characteristics of auxiliary verbs 106

Table 6.2 Auxiliaries and their axes 114

Table 6.3 Some nite, lexical, and auxiliary verbs 119

Table 7.1 Terms for clauses 140

Table 8.1 Embedded clause 152

Table 8.2 e non-nite CP 154

Table 9.1 Components of the PP, AdjP, and AdvP 172

Table 9.2 Examples of nouns with modiers and with complements 174

Table 9.3 Functions inside the NP 175

Table 9.4 Modiers and complements to N: a summary 179

Table 10.1 Restrictive and Non-Restrictive RC 191

Table 10.2 Relative Clauses and Complement Clauses 192

Table 10.3 Examples of Reduced RC 193

Table 10.4 e sisters of CP 198

Chapter 1

Introduction

1. Examples of linguistic knowledge

2. How do we know so much?

3. Examples of social or non-linguistic knowledge

4. Conclusion

All of us know a lot about language. Most of the time, however, we are not conscious

of this knowledge. When we actually study language, we attempt to nd out what

we know and how we acquire this linguistic knowledge. In this chapter, a number of

instances will be given of what speakers of English intuitively or subconsciously know

about the grammar of English, both about its sounds and its structure. e remainder

of the book focuses on syntax, i.e. the categories, phrases, and the functions of phrases to

account for our intuitive knowledge. e chapter also discusses social, i.e. non-linguistic,

rules. ese are oen called prescriptive rules and some of these prescriptive rules are

dealt with as ‘special topics’ at the end of each chapter.

1.

Examples of linguistic knowledge

Speakers of a language know a lot about their languages. For instance, we know about

the sounds (phonology), the structure of words (morphology), and the structure of

sentences (syntax).

1.1

Sounds and words

If you are a native speaker of English, you know when to use the article a and when

to use an. All of us know how to do this correctly though we might not be able to

formulate the rule, which says that the article a occurs before a word that starts with a

consonant, as in (1), and an occurs before a word that starts with a vowel, as in (2):

(1) a nice person, a treasure

(2) an object, an artist

2 An Introduction to the Grammar of English

If a child is given a nonsense word, such as those in (3), the child knows what form of

the article to use:

(3) ovrite, cham

e rule for a(n) does not need to be taught explicitly in schools. It is only mentioned in

connection with words that start with h or u. Teachers need to explain that what looks

like a vowel in writing in (4) is not a vowel in speech and that the a/an rule is based on

spoken English. So, the form we choose depends on how the word is pronounced. In

(4) and (5), the u and h are not pronounced as vowels and hence the article a is used.

In (6) and (7), the initial u and h are pronounced as vowels and therefore an is used:

(4) a union, a university

(5) a house, a hospital

(6) an uncle

(7) an hour

e same rule predicts the pronunciation of the in (8). Pronounce the words in (8) and

see if you can state the rule for the use of the:

(8) e man, the table, the object, the hospital...

Examples (1) to (8) show the workings of a phonological (or sound) rule. e assumption

is that we possess knowledge of consonants and vowels without having been taught

the distinction. In fact, knowledge such as this enables us to learn the sound system

of the language.

Apart from the structure of the sound system, i.e. the phonology, a grammar will have

to say something about the structure of words, i.e. the morphology. Speakers are quite cre-

ative building words such as kleptocracy, cyberspace, antidisestablishmentarianisms, and

even if you have never seen them before, knowing English means that you will know

what these words mean based on their parts. Words such as occinaucinihilipilication,

meaning ‘the categorizing of something as worthless or trivial’, may be a little more dif-

cult. is book will not be concerned with sounds or with the structure of words; it

addresses how sentences are structured, usually called syntax. In the next subsection,

some examples are given of the syntactic knowledge native speakers possess.

1.2

Syntactic structure

Each speaker of English has knowledge about the structure of a sentence. is is obvi-

ous from cases of ambiguity where sentences have more than one meaning. is oen

makes them funny. For instance, the headline in (9) is ambiguous in that ‘cello case’

can mean either a ‘court case related to a cello or someone called Cello’ or ‘a case to

protect a cello’:

Chapter 1. Introduction 3

(9) Drunk Gets Ten Months In Cello Case.

In (9), the word ‘case’ is ambiguous. We call this lexical ambiguity since the ambiguity

depends on one word’s multiple meanings. e headlines in (10) to (12) are funny

exactly because drops, le, waes, strikes and idle are ambiguous:

(10) Eye drops o shelf.

(11) British le waes on Falkland Islands.

(12) Teacher strikes idle kids.

Word ambiguities such as (10) to (12) are oen produced on purpose for a certain

eect, and are also called ‘puns’. Some well-known instances from Lewis Carroll appear

in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1. Alice’s Ambiguities

“Mine is a long and sad tale!” said the Mouse, turning to Alice and sighing. “It is a long tail,

certainly,” said Alice, looking with wonder at the Mouse’s tail, “but why do you call it sad?”

“How is bread made?” “I know that!” Alice cried eagerly. “You take some our -” “Where do you

pick the ower?” the White Queen asked. “In a garden, or in the hedges?” “Well, it isn’t picked at

all,” Alice explained; “it’s ground-” “How many acres of ground?” said the White Queen.

ere are also sentences where the structure is ambiguous, e.g. (13) and (14). In

(13), the monkey and elephant can both be carried in or just the monkey is. In (14),

planes can be the object of ying or the subject of the sentence:

(13) Speaker A: I just saw someone carrying a monkey and an elephant go into the circus.

Speaker B: Wow, that someone must be pretty strong.

(14) Flying planes can be dangerous.

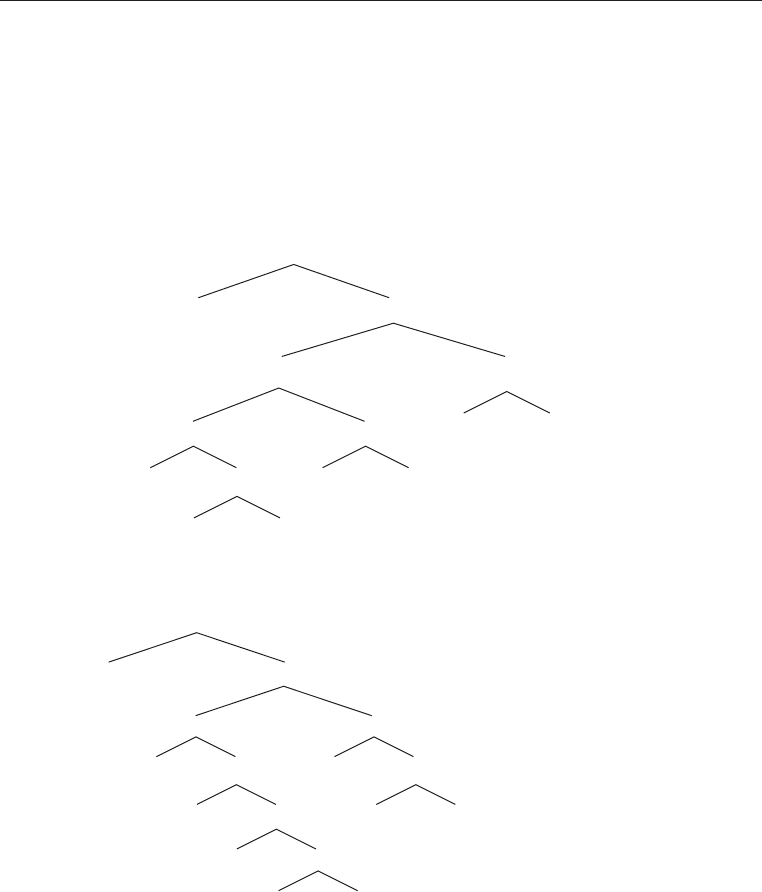

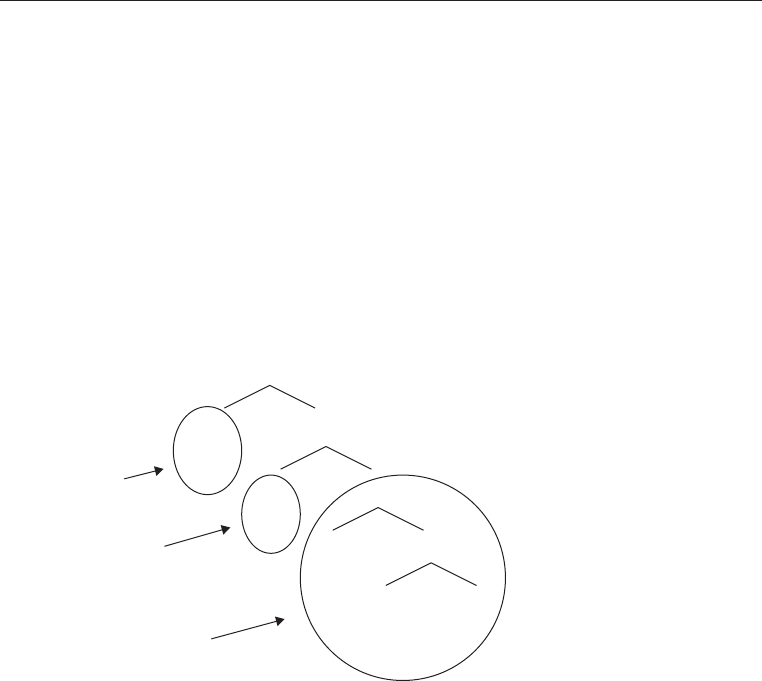

Cartoons thrive on ambiguity and the combination of the unambiguous visual

representation with the ambiguous verbal one often provides the comic quality, as

in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1. Structural Ambiguity (Hi & Lois king features syndicate)

4 An Introduction to the Grammar of English

e aim of this book is to understand the structure of English sentences; ambiguity

helps understand that structure, and we’ll come back to it in Chapter 3.

Knowing about the structure of a sentence, i.e. what parts go with other parts, is

relevant in many cases. In a yes/no question, the verb (in bold) is moved to the front of

the sentence, as from (15) to (16):

(15) e man is tall.

(16) Is the man tall?

is rule is quite complex, however. Starting from (17), we can’t simply front any verb,

as (18) and (19) show. In (18), the rst verb of the sentence is fronted and this results

in an ungrammatical sentence (indicated by the *); in (19), the second verb is fronted

and this is grammatical:

(17) e man who is in the garden is tall.

(18) *Is the man who in the garden is tall?

(19) Is the man who is in the garden tall?

ese sentences show that speakers take the structure of a sentence into account when

formulating questions (see also Chapter 3). We intuitively know that the man who is in

the garden is a single unit and that the second verb is the one we need to move in order

to make the question. is is not all, however. We also need to know that not all verbs

move to form questions, as (20) shows:

(20) *Arrived the bus on time?

Only certain verbs, namely auxiliaries (see Chapter 6) and the verb to be, as in (16) and

(19), are fronted.

Apart from yes/no questions, where the expected answer is yes or no, there are

wh

questions, where more information is expected for an answer. In these sentences, the

wh-word is fronted as well as the auxiliary did. In (21), who is the object (see Chapter 4)

of the verb meet and we can check that by putting the object ‘back’, as in (22), which is

possible only with special intonation:

(21) Who did Jane meet?

(22) Jane met WHO?

is rule too is complex. Why would (23a) be grammatical but (23b) ungrammatical?

(23) a. Who did you believe that Jane met?

b. *Who did you believe the story that Jane met?

Without ever having been taught this, native and most non-native speakers know

that about the dierence between (23a) and (23b). With some trouble, we can gure

out what (23b) means. ere is a story that Jane met someone and you believe

this story. e speaker in (23b) is asking who that someone is. Sentence (23b) is

Chapter 1. Introduction 5

ungrammatical because who moves ‘too far’. It is possible, but not necessary here, to

make precise what ‘too far’ means. e examples merely serve to show that speakers

are aware of structure without explicit instruction and that who moves to the initial

position.

us, speakers of English know that (a) sentences are ambiguous, e.g. (13)

and (14), (b) sentences have a structure, e.g. (17), (c) movement occurs in ques-

tions, e.g. in (16) and (21), and (d) verbs are divided into (at least) two kinds: verbs

that move in questions, as in (19), and verbs that don’t move, as in (20). Chapter 3

will give more information on the rst two points, Chapter 11 on the third point,

and Chapter 6 on the dierence between auxiliaries and main verbs. e other

chapters deal with additional kinds of grammatical knowledge. Chapter 2 is about

what we know regarding categories; Chapter 4 is about functions such as subject

and object; Chapter 5 about adverbials and objects; Chapter 9 about the struc-

ture of a phrase; and Chapters 7, 8, and 10 about the structure of more complex

sentences.

2.

How do we know so much?

In Section 1, we discussed examples of what we know about language without being

explicitly taught. How do we come by this knowledge? One theory that accounts for

this is suggested by Noam Chomsky. He argues that we are all born with a language

faculty that when “stimulated by appropriate and continuing experience, … creates

a grammar that creates sentences with formal and semantic properties” (1975: 36).

us, our innate language faculty (or Universal Grammar) enables us to create a set of

rules, or grammar, by being exposed to (rather chaotic) language around us. e set

of rules that we acquire enables us to produce sentences we have never heard before.

ese sentences can also be innitely long (if we have the time and energy). Language

acquisition, in this framework, is not imitation but an interaction between Universal

Grammar and exposure to a parti cular language.

is need for exposure to a particular language explains why, even though we

all start out with the same Language Faculty or Universal Grammar, we acquire

slightly dierent grammars. For instance, if you are exposed to a certain variety of

Missouri or Canadian English, you might use (24); if exposed to a particular variety

of British English, you might use (25); or, if exposed to a kind of American English,

(26) and (27):

(24) I want for to go.

(25) You know as she le. (meaning ‘You know that she le’)

(26) She don’t learn you nothing.

(27) Was you ever bit by a bee?

6 An Introduction to the Grammar of English

us, “[l]earning is primarily a matter of lling in detail within a structure that is

innate” (Chomsky 1975: 39). “A physical organ, say the heart, may vary from one

person to the next in size or strength, but its basic structure and its function within

human physiology are common to the species. Analogously, two individuals in the

same speech community may acquire grammars that dier somewhat in scale and

subtlety. . . . ese variations in structure are limited . . .” (p. 38).

Hence, even though Universal Grammar provides us with categories such as

nouns and verbs that enable us to build our own grammars, the language we hear

around us will determine the particular grammar we build up. A person growing

up in the 14th century heard multiple negation, as in (28), and would have had

a grammar that allowed multiple negation. e same holds for a person from the

15th century who has heard (29). e Modern English equivalents, given in the

single quotation marks, show that many varieties of English now use ‘any’ instead of

another negative:

(28) Men neded not in no cuntre A fairer body for to seke.

‘People did not need to seek a fairer person in any country.’

(Chaucer, e Romaunt of the Rose, 560–1)

(29) for if he had he ne nedid not to haue sent no spyes.

‘because if he had, he would not have needed to send any spies.’

(e Paston Letters, letter 45 from 1452)

Linguists typically say that one variety of a language is just as ‘good’ as any other. Peo-

ple may judge one variety as ‘bad’ and another as ‘good’, but for most people studying

language, (24) through (27) are just interesting, not ‘incorrect’. is holds for language

change as well: the change from (28) and (29) to Modern English is not seen as either

‘progress’ or ‘decay’, but as a fact to be explained. Languages are always changing and

the fascinating part is to see the regularities in the changes.

Society has rules about language, which I call social or ‘non-linguistic’, and which

we need to take into account to be able to function. ese are occasionally at odds with

the (non-prescriptive) grammars speakers have in their heads. is is addressed in the

next section.

3.

Examples of social or non-linguistic knowledge

We know when not to make jokes, for instance, when lling out tax forms or speaking

with airport security people. We also know not to use words and expressions such

as all you guys, awesome, and I didn’t get help from nobody in formal situations such as

applying for a job or in a formal presentation. Using dude

in the situation of Figure 1.2

may not be smart either. We learn when and how to be polite and impolite; formal

Chapter 1. Introduction 7

and informal. e rules for this dier from culture to culture and, when we learn

a new language, we also need to learn the politeness rules and rules for greetings,

requests, etc.

Figure 1.2. How to use ‘dude’! (Used with the permission of Mike Twohy and the Cartoonist

Group. All rights reserved)

When you are in informal situations (e.g. watching TV with a friend), everyone

expects ‘prescriptively proscribed’ expressions, such as (30). In formal situations (testify-

ing in court), you might use (31) instead:

(30) I didn’t mean nothin’ by it.

(31) I didn’t intend to imply anything with that remark.

e dierences between (30) and (31) involve many levels: (a) vocabulary choice,

e.g. mean rather than intend, (b) phonology, e.g. nothin

’ for nothing, (c) syntax, namely

the two negatives in (30) that make one negative, and (d) style, e.g. (30) is much less

explicit. People use the distinction between formal and informal for ‘eect’ as well, as

in (32):

(32) You should be better prepared the next time you come to class. Ain’t no way I’m

gonna take this.

8 An Introduction to the Grammar of English

Style and grammar are oen equated but they are not the same. Passive constructions,

for instance, occur in all languages, and are certainly grammatical. ey are oen advised

against for reasons of style because the author may be seen as avoiding taking responsibility

for his or her views. In many kinds of writing, e.g. scientic, passives are very frequent.

is book is not about the ght between descriptivism (‘what people really say’)

and prescriptivism (‘what some people think other people ought to say’). As with all

writing or speech, this book makes a number of choices, e.g. use of contractions,

1

use

of ‘I’ and ‘we’ as well as a frequent use of passives, and avoidance of very long sentences.

is, however, is irrelevant to the main point which is to provide the vocabulary and

analytical skills to examine descriptive as well as prescriptive rules. e eld that exam-

ines the status of prescriptive rules, regional forms as in (24) to (27), and formal and

informal language, as in (30) to (32), is called sociolinguistics.

Some prescriptive rules are analysed in the special topics sessions at the end of

every chapter. e topics covered are split innitives (

to boldly go where . . .), adverbs

and adjectives, multiple negation, as in (30), case marking and subject–verb agree-

ment, the use of passives, the use of of rather than have (I should of done that), the

preposition like used as a complementizer (like I said ...), dangling modiers, singular

and plural pronouns, relative pronouns, and the ‘correct’ use of commas. ere are

many more such rules.

4.

Conclusion

is rst chapter has given instances of rules we know without having been taught

these rules explicitly. It also oers an explanation about why we know this much:

Universal Grammar ‘helps’ us. Other chapters in the book provide the categories and

structures that we must be using to account for this intuitive knowledge. e chapter

also provides instances of social or non-linguistic rules. ese are oen called pre-

scriptive rules and some of these are dealt with as ‘special topics’ at the end of each of

the chapters. is chapter’s special topic discusses one of the more infamous prescrip-

tive rules, namely the split innitive.

e key terms in this chapter are syntax; lexical and structural ambiguity; puns;

linguistic as opposed to social or non-linguistic knowledge; descriptive as opposed

to prescriptive rules; formal as opposed to informal language; innate faculty; and

Universal Grammar.

1. A copy-editor for the first edition changed the contracted forms to full ones, however, and I

haven’t put the contractions back where they had been changed.

Chapter 1. Introduction 9

Exercises

A. Using the words lexical and structural ambiguity, explain the ambiguity in (33) to (37):

(33) light house keeper

(34) old dogs and cats

(35) She gave her dog biscuits.

(36) Speaker A: Is your fridge running?

Speaker B: Yes.

Speaker A: Better go catch it!

(37) Fish are smart. They always swim in schools.

B. Do you think the following sentences are prescriptively correct or not. Why/why not?

(38) It looks good.

(39) Me and my friend went out.

(40) Hopefully, hunger will be eliminated.

(41) There’s cookies for everyone.

Class discussion

C. Can you think of something you would say in an informal situation but not in a formal one?

Suggestion: If you have access to the internet, check the British National Corpus (BNC at

http://www.natcorp.ox.ac.uk/) or the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA

at http://www.americancorpus.org/) to see if this use is found. If you wonder what a

corpus is, it is a carefully selected set of texts that represents the language of a particular

time or variety (British in the case of the BNC and American in the case of the COCA).

D.

Has your English ever been corrected? Can you remember when?

E. List some stylistic rules. In the text, I mentioned the avoidance of the passive. You might

check http://www.libraryspot.com/grammarstyle.htm with links to a collection of

grammar and style books.

F.

Discuss why prescriptively ‘correct’ constructions are often used in formal situations.

G. You may have heard of best-selling ‘language mavens’ such as William Sare or Edwin

Newman. Sare was a political commentator who also wrote a weekly column in the

Sunday New York Times. Titles of his books include Good Advice, I Stand Corrected: More

on Language, and Language Maven Strikes Again. Newman, a former NBC correspondent,

writes books entitled A Civil Tongue and Strictly Speaking. These lead reviewers to say

“Read Newman! Save English before it is fatally slain.” (backcover)

– Why are there language authorities?

– Why do people listen to them?

H. Have you seen titles such as ‘An History of the English Language’? Is this correct according

to our rule in Section 1.1? Google it and see if ‘a history’ or ‘an history’ is more frequent.

10 An Introduction to the Grammar of English

Keys to the exercises

A. (33) shows structural ambiguity: [[light house] keeper] or [light][house keeper].

(34) shows structural ambiguity: [old dogs] and [cats] or [old [dogs and cats]]

(35) again shows structural ambiguity: She gave [her] [dog biscuits] or She gave [her

dog] [biscuits].

(36) shows lexical ambiguity: running can be physical running or running as an

engine does.

(37) shows lexical ambiguity: schools has two meanings.

B. (38) is ok since good is an adjective giving more information about the pronoun it

(see Chapter 2 and special topic).

(39) is not prescriptively correct since the subject should get nominative case (see Chapter 4

and special topic) and because many people are taught not to start with themselves rst.

(40) is not since hopefully is not supposed to be used as a sentence adverb, i.e. an adverb

that says something about the attitude of the speaker (see Chapter 5 and special topic of

Chapter 2).

(41) is not since the verb is singular (is) and the subject is plural (cookies). This violates

subject-verb agreement (see Chapters 3 and 4).

Special topic: Split innitive

In a later chapter, we will discuss innitives in great detail. For now, I just want to discuss the

prescriptive rule against splitting innitives that almost everyone knows and show that split

innitives have occurred in English at least for 700 years.

Innitives are verbs preceded by a to that is not a preposition but an innitive marker.

Some examples are given in (42) to (44), where the innitive and its marker are in bold:

(42) To err is human.

(43) It is nice to wander aimlessly.

(44) To be or not to be is to be decided.

The prescriptive rule is not to split this innitive from its marker, as stated in (45):

(45) Do not separate an innitival verb from its accompanying to, as in Star Trek’s ‘to

boldly go where no man has gone before’.

2

2. This is the version from the early episodes of Star Trek which was much criticized for the split

innitive. Later episodes changed no man to no one and that’s how the 2009 lm version has it.

Chapter 1. Introduction 11

Swan writes that “[s]plit innitive structures are quite common in English, especially in an

informal style. A lot of people consider them ‘bad style’, and avoid them if possible, placing the

adverb before the to, or in end-position in the sentence” (1980: 327). Fowler writes as follows:

The English-speaking world may be divided into (1) those who neither know nor care what a

split innitive is; (2) those who do not know but care very much; (3) those who know & condemn;

(4) those who know & approve; & (5) those who know & distinguish. (1926 [1950]: 558)

Fowler himself disapproves of the use of the split innitive. Quirk & Greenbaum are less critical.

The inseparability of to from the innitive is . . . asserted in the widely held opinion that it is bad

style to ‘split the innitive’. Thus rather than:

?He was wrong to suddenly leave the country

many people (especially in BrE) prefer:

He was wrong to leave the country suddenly

It must be acknowledged, however, that in some cases the ‘split innitive’ is the only tolerable

ordering, since avoiding the ‘split innitive’ results in clumsiness or ambiguity. (1973: 312)

Split innitives have occurred from the Middle English period, i.e. from 1200, on, as (46) to (52) show.

(46) I want somebody who will be on there not to legislate from the bench but to

faithfully interpret the constitution. (George Bush, quoted in The Economist,

6 July 1991)

(47) Remember to always footnote the source.

(48) [This] will make it possible for everyone to gently push up the fees. (New York

Times, 21 July 1991)

(49) . . .to get the Iraqis to peacefully surrender... (New York Times, 7 July 1991)

(50) fo[r] to londes seche

‘To see countries.’ (Layamon Brut Otho 6915, early 13th century)

(51) Y say to 3ou, to nat swere on al manere

‘I say to you to not curse in all ways.’ (Wyclif, Matthew 5, 34, late 14th century)

(52) Poul seiþ, þu þat prechist to not steyl, stelist,

‘Paul says that you who preaches to not steal steals.’ (Apology for the Lollards 57,

late 14th century)

Would you change these? If so, how? In this book, I have not avoided them on purpose and

know of at least one instance where I have split an innitive.

Chapter 2

Categories

1. Lexical categories

2. Grammatical categories

3. Pronouns

4. What new words and loanwords tell us!

5. Conclusion

In this chapter, I provide descriptions of the categories or parts of speech. Categories

can be divided into two main classes: lexical and functional. e lexical categories

include Noun, Verb, Adjective, Adverb, and Preposition and are called lexical because

they carry lexical meaning. ey are also called content words since they have syn-

onyms and antonyms. As we’ll see in the next chapter, syntactically, lexical categories

are the heads of phrases.

ere are also functional or grammatical categories: Determiner, Auxiliary, Coor-

dinator, and Complementizer. ese categories are called grammatical or functional

categories since they do not contribute much to the meaning of a sentence but deter-

mine the syntax of it. ey do not function as heads of phrases but merely as parts or

as connectors. I’ll refer to them as grammatical categories. Prepositions and adverbs

are a little of both as will be explained in Sections 1.2 and 1.3 respectively, as are pro-

nouns, e.g. it, she, and there, to be discussed in Section 3.

When languages borrow new words, these will mainly be nouns, verbs, and adjec-

tives, i.e. lexical categories. erefore, the dierence between lexical and grammatical

is oen put in terms of open as opposed to closed categories, the lexical categories

being open (new words can be added) and the grammatical ones being closed (new

words are not easily added). Section 4 will examine this in a limited way.

.

Lexical categories

e ve lexical categories are Noun, Verb, Adjective, Adverb, and Preposition. ey

carry meaning, and often words with a similar (synonym) or opposite meaning

Chapter 2. Categories

(antonym) can be found. Frequently, the noun is said to be a person, place, or thing

and the verb is said to be an event or act. ese are semantic denitions. In this chapter,

it is shown that semantic denitions are not completely adequate and that we need to

dene categories syntactically (according to what they combine with) and morpholog-

ically (according to how the words are formed). For example, syntactically speaking,

chair is a noun because it combines with the article (or determiner) the; morphologi-

cally speaking, chair is a noun because it takes a plural ending as in chairs.

.

Nouns (N) and Verbs (V)

A noun generally indicates a person, place or thing (i.e. this is its meaning). For

instance, chair, table, and book are nouns since they refer to things. However, if the

distinction between a noun as person, place, or thing and a verb as an event or action

were the only distinction, certain nouns such as action and destruction would be verbs,

since they imply action. ese elements are nevertheless nouns.

In (1) and (2), actions and destruction are preceded by the article the, actions can be

made singular by taking the plural -s o, and destruction can be pluralized with an -s.

is makes them nouns:

(1) e actions by the government came too late.

(2) e hurricane caused the destruction of the villages.

As will be shown in Chapter 4, their functions in the sentence are also typical for

nouns rather than verbs: in (1), actions is part of the subject, and in (2), destruction

is part of the object.

Apart from plural -s, other morphological characteristics of nouns are shown

in (3) and (4). Possessive ’s (or genitive case) appears only on nouns or noun phrases,

e.g. the noun Jenny in (3), and axes such as -er and -ism, e.g. writer and postmodern-

ism in (4), are also typical for nouns:

(3) Jenny ’s neighbor always knows the answer.

(4) at writer has modernized postmodernism.

Syntactic reasons for calling nouns nouns are that nouns are oen preceded by the,

as actions and government are in (1), as destruction and villages are in (2), and as

answer is in (3). Nouns can also be preceded by that, as in (4), and, if they are fol-

lowed by another noun, there has to be a preposition, such as by in (1) and of in (2),

connecting them.

e nouns action and destruction have verbal counterparts, namely act and destroy,

and (1) and (2) can be paraphrased as (5) and (6) respectively:

(5) e government acted too late.

(6) e hurricane destroyed the villages.

Just as nouns cannot always be dened as people or things, verbs are not always acts,

even though acted and destroyed are. e verb be in (7), represented by the third

An Introduction to the Grammar of English

person present form is, does not express an action. Hence, we need to add state to the

semantic denition of verb, as well as emotion to account for sentences such as (8):

(7) e book is red and blue.

(8) e book seemed nice (to me).

Some of the morphological characteristics of verbs are that they can express tense,

e.g. past tense ending -ed in (5), (6), and (8); that the verb ends in -s when it has a

third person singular subject (see Chapter 4) and is present tense; and that it may have

an ax typical for verbs, namely -ize, e.g. in modernized in (4) (note that it is -ise in

British English). Syntactically, they can be followed by a noun, as in (6), as well as by

a preposition and they can be preceded by an auxiliary, as in (4). Some of the major

dierences between nouns and verbs are summarized in Table 2.1 below.

Table 2.1. Some dierences between N(oun) and V(erb)

Noun (N) Verb (V)

Morphology a. plural -s with a few exceptions,

e.g. children, deer, mice

h. past tense -ed with a few

exceptions, e.g. went, le

b. possessive ’s i. third person singular

agreement -s

c. some end in -ity, -ness -ation, -er,

-ion, -ment

j. some end in -ize,-ate

Syntax d. may follow the/a and this/that/

these/those

k. may follow an auxiliary

e.g. have and will

e. may be modied by adjective l. may be modied by adverb

f. may be followed by preposition

and noun

m. may be followed by noun or

preposition and noun

Semantics g. person, place, thing n. act, event, state, emotion

In English, nouns can easily be used as verbs and verbs as nouns. erefore, it is

necessary to look at the context in which a word occurs, as in (9), for example, where

Shakespeare uses vnckle, i.e. ‘uncle’, as a verb as well as a noun:

(9) York: Grace me no Grace, nor Vnckle me,

I am no Traytors Vnckle; and that word Grace

In an vngracious mouth, is but prophane.

(Shakespeare, Richard II, II, 3, 96, as in the First Folio edition)

us, using the criteria discussed above, the rst instance of ‘uncle’ would be a verb

since the noun following it does not need to be connected to the verb by means of a

preposition, and the second ‘uncle’ is a noun since ‘traitor’ has the possessive ’s. Note

that I have le Shakespeare’s spelling, punctuation, and grammar as they appear in the

First Folio Edition.

Chapter 2. Categories

Other examples where a word can be both a noun and a verb are table, to table;

chair, to chair; oor, to oor; book, to book; fax, to fax; telephone, to telephone; and walk,

to walk. Some of these started out as nouns and some as verbs. For instance, fax is the

shortened form of the noun facsimile which became used as a verb as well. Currently,

when people say fax, they oen mean pdf (portable document format), another noun

that is now used as a verb. A sentence where police is used as noun, verb, and adjective

respectively is (10a); (10b) is nicely alliterating where pickle is used as a verb, adjective,

and noun; and (10c) has fast as adjective, adverb, and noun:

(10) a. Police police police outings regularly in the meadows of Malacandra.

b. Did Peter Piper pickle pickled pickles?

(Alyssa Bachman’s example)

c. e fast girl recovered fast aer her fast.

(Amy Shinabarger’s example)

As we’ll see, other words can be ambiguous in this way.

As a summary to Section 1.1, use Table 2.1. Not all of these properties are always

present of course. Morphological dierences involve the shape of an element while

syntactic ones involve how the element ts in a sentence. e semantic dierences

involve meaning, but remember to be careful here since nouns, for instance, can have

plural -s in (1) and (2) above.

Dierences (e) and (l) will be explained in the next section. ey are evident in

(11), which shows the adjective expensive that modies (i.e. says something about) the

noun book and the adverb quickly that modies the verb sold out:

(11) at expensive book sold out quickly.

. Adjectives (Adj) and Adverbs (Adv)

Adverbs and Adjectives are semantically very similar in that both modify another ele-

ment, i.e. they describe a quality of another word: quick/ly, nice/ly, etc. As just men-

tioned, the main syntactic distinction is as expressed in (12):

(12) e Adjective-Adverb Rule

An adjective modies a noun;

an adverb modies a verb and (a degree adverb) modies an adjective or adverb.

Since an adjective modies a noun, the quality it describes will be one appropri-

ate to a noun, e.g. nationality/ethnicity (American, Navajo, Dutch, Iranian), size (big,

large, thin), age (young, old), color (red, yellow, blue), material/personal description

(wooden, human), or character trait (happy, fortunate, lovely, pleasant, obnoxious).

Adverbs oen modify actions and will then provide information typical of those,

e.g. manner (wisely, fast, quickly, slowly), or duration (frequently, oen), or speaker

An Introduction to the Grammar of English

attitude (fortunately, actually), or place (there, abroad), or time (then, now, yesterday).

As well and also, and negatives such as not and never, are also adverbs in that they

usually modify the verb.

When adverbs modify adjectives or other adverbs, they are called degree adverbs

(very, so, too). ese degree adverbs have very little meaning (except some that can

add avor to the degree, such as exceedingly and amazingly) and it is hard to nd

synonyms or antonyms. It therefore makes more sense to consider this subgroup of

adverbs grammatical categories. ey also do not head a phrase of their own, and

when it looks as if they do, there really is another adjective or adverb le out. e very

in (13) modies important, which is le out:

(13) How important is your job to you? Ver y.

(from CBS 60 Minutes 1995).

Some instances of the use of the adjective nice are given in (14) and (15). Traditionally,

the use in (14) is called predicative and that in (15) attributive:

(14) e book is nice.

(15) A nice book is on the table.

e adverbs very and quickly appear in (16) and (17):

(16) is Hopi bowl is very precious.

(17) He drove very quickly.

In (14) and (15), nice modies the noun book. In (16), the degree adverb very modi-

es the adjective precious; and in (17), it modies the adverb quickly, which in its turn

modies the verb drove. (We will come back to some of the issues related to the precise

nature of the modication in Chapters 3, 4, and 9). In the ‘special topic’ section at the

end of this chapter, it will be shown that speakers oen violate rule (12), but that these

so-called violations are rule-governed as well.

Sentence (16) shows something else, namely that the noun Hopi can also be used

to modify another noun. When words are put together like this, they are called com-

pound words. Other examples are given in (18) and (19):

(18) So the principal says to the [chemistry teacher], “You’ll have to teach physics this

year.” (from Science Activities 1990)

(19) Relaxing in the living room of his unpretentious red [stone house], …

(from Forbes 1990)

Some of these compounds may end up being seen or written as one word; others are

two words e.g. girlfriend, bookmark, mail-carrier, re engine, dog food, and stone age.

When we see a noun modifying another noun, as in (18) and (19), we will discuss if

they are compounds or not. e space and hyphen between the two words indicate

degrees of closeness.

Chapter 2. Categories

Oen, an adverb is formed from an adjective by adding -ly, as in (17). However,

be careful with this morphological distinction: not all adverbs end in -ly, e.g. fast,

and hard can be adjectives as well as adverbs and some adjectives end in -ly,

e.g. friendly, lovely, lively, and wobbly. If you are uncertain as to whether a word is an

adjective or an adverb, either look in a dictionary to see what it says, or use it in a

sentence to see what it modies. For instance, in (20), fast is an adjective because it

modies the noun car, but in (21), it is an adverb since it modies the verb drove:

(20) at fast car must be a police car.

(21) at car drove fast until it saw the photo radar.

In a number of cases, words such as hard and fast can be adjectives or adverbs, depend-

ing on the interpretation. In (22), hard can either modify the noun person, i.e. the

person looks tough or nasty, in which case it is an adjective, or it can modify look

(meaning that the person was looking all over the place for something, i.e. the eort

was great) in which case hard is an adverb:

(22) at person looked hard.

As a reader of this sentence, what is your preference? Checking a contemporary

American corpus, i.e. a set of representative texts, I found that most speakers use hard

as an adverb aer the verb look. Do you agree?

Some of the ‘discrepancies’ between form and function are caused by language change.

For instance, the degree adverb very started out its life being borrowed as an adjective from

the French verrai (in the 13th century) with the meaning ‘true’, as in (23):

(23) Under the colour of a veray peax, whiche is neuertheles but a cloked and furred peax.

‘Under the color of a true peace, which is nevertheless nothing but a cloaked and

furred peace.’ (Cromwell’s 16th century Letters)

Here, what looks like a -y ending is a rendering of the Old French verrai. What’s worse for

confusing Modern English speakers is that, in Old English, adverbs did not need to end in

-lich or -ly. at’s why ‘old’ adverbs sometimes keep that shape, e.g. rst in (24) is a ‘correct’

adverb, but second is not. e reason that secondly is prescribed rather than second is that

it was borrowed late from French, at a time when English adverbs typically received -ly

endings.

(24) … first I had to watch the accounts and secondly I’m looking at all this stu for

when I start my business. (from a conversation in the BNC Corpus)

A last point to make about adjectives and adverbs is that most (if they are gradable)

can be used to compare or contrast two or more things. We call such forms the com-

parative (e.g. better than) or superlative (e.g. the best). One way to make these forms is

to add -er/-est, as in nicer/nicest. Not all adjectives/adverbs allow this ending, however;

An Introduction to the Grammar of English

some need to be preceded by more/most, as in more intelligent, most intelligent. Some-

times, people are creative with comparatives and superlatives, especially in advertising,

as in (25) and (26), or in earlier forms as in (27):

(25) mechanic: “the expensivest oil is …”

(26) advertisement: “the bestest best ever phone”.

(27) To take the basest and most poorest shape … (Shakespeare, King Lear II, 3, 7)

ere are also irregular comparative and superlative forms, such as good, better, best;

bad, worse, worst. ese have to be learned as exceptions to the rules, and can be played

with, as in the pun ‘When I am bad, I am better’.

To summarize this section, I’ll provide a table listing dierences between adjectives

and adverbs. Not all of these dierences have been discussed yet, e.g. the endings -ous, -ary,

-al, and -ic are typical for adjectives and -wise, and -ways for adverbs, but they speak for

themselves.

Table 2.2. Dierences between adjectives and adverb

Adjectives (Adj) Adverbs (Adv)

Morphology a. end in -ous, -ary, -al, -ic;

mostly have no -ly;

and can be participles

d. end in -ly in many cases, -wise,

-ways, etc. or have no ending

(fast, now)

Syntax b. modify N e. modify V, Adj, or Adv

Semantics c. describe qualities typical of nouns,

e.g: nationality, color, size

f. describe qualities of verbs,

e.g: place, manner, time,

duration, etc. and of adjectives/

adverbs: degree

. Prepositions (P)

Prepositions typically express place or time (at, in, on, before), direction (to, from, into,

down), causation (for), or relation (of, about, with, like, as, near). ey are invariable

in form and have to occur before a noun, as (28) shows, where the prepositions are in

bold and the nouns they go with are underlined:

(28) With their books about linguistics, they went to school.

On occasion, what look like prepositions are used on their own, as in (29):

(29) He went in; they ran out; and he jumped down.

In such cases, these words are considered adverbs, not prepositions. e dierence

between prepositions and adverbs is that prepositions come before the nouns they

relate to and that adverbs are on their own.

Some other examples of one word prepositions are during, around, aer, against,

despite, except, without, towards, until, till, and inside. Sequences such as instead of,

Chapter 2. Categories

outside of, away from, due to, and as for are also considered to be prepositions, even

though they consist of more than one word. Infrequently, prepositions are transformed

into verbs, as in (30):

(30) ey upped the price.

Some prepositions have very little lexical meaning and are mainly used for grammati-

cal purposes. For instance, of in (31) expresses a relationship between two nouns rather

than a locational or directional meaning:

(31) e door of that car.

Prepositions are therefore a category with lexical and grammatical characteristics.

Here, however, I will treat them as lexical, for the sake of simplicity. A partial list is

given in Table 2.3.

Table 2.3. Some prepositions in English

about, above, across, aer, against, along, amidst, among, around, at, before, behind, below,

beneath, beside(s), between, beyond, by, concerning, despite, down, during, except, for, from, in,

into, inside, like, near, of, o, on, onto, opposite, outside, over, past, since, through, to, toward(s),

under, underneath, until, up, upon, with, within, without

. Grammatical categories

e main grammatical categories are Determiner, Auxiliary, Coordinator, and Com-

plementizer. As also mentioned above, it is hard to dene grammatical categories in

terms of meaning because they have very little. eir function is to make the lexical

categories t together.

.

Determiner (D)

e determiner category includes the articles a(n) and the, as well as demonstratives,

possessive pronouns, possessive nouns, some quantiers, some interrogatives, and

some numerals. So, determiner (or D) is an umbrella term for all of these. Determin-

ers occur with a noun to specify which noun is meant or whose it is. If you are a native

speaker, you know how to use the indenite article a and the denite article the. For

non-native speakers, guring out their use is very dicult.

e indenite article is oen used when the noun that follows it is new in the text/

conversation, such as the rst mention of Florida manatee in (32) is. e second and

third mentions of it are preceded by the denite article the:

(32) e fate of a Florida manatee that has wandered into northern New Jersey waters

remained unclear Saturday night. e wayward male – known as Ilya – has been

An Introduction to the Grammar of English

stuck near a Linden oil renery, and ocials say plunging temperatures and a lack of

food were endangering its life. And while the gentle sea cow appears to be in good

health, it had been huddling near an outfall pipe at an oil renery – the only place it

could nd warm water. (from Hungton Post)

ere are four demonstratives in English: this, that, these, and those, with the rst two

for singular nouns and the last two for plural ones. See (33a). Possessive pronouns

include my, your, his, her, its, our, and their, as in (33b). Nouns can be possessives as

well, but in that case they have an -’s (or ’) ending, as in (33c):

(33) a. at javelina loved these trails.

b. eir kangaroo ate my food.

c. Gucci’s food was eaten by Coco.

3

In (33b), their and my specify whose kangaroo and whose food it was, and the posses-

sive noun Gucci’s in (33c) species whose food was eaten.

Determiners, as in (32) and (33), precede nouns just like adjectives, but whereas

a determiner points out which entity is meant (it species), an adjective describes the

quality (it modies). When both a determiner and an adjective precede a noun, the

determiner always precedes the adjective, as in (34a), and not the other way round, as

in (34b) (indicated by the asterisk):

(34) a. eir irritating dog ate my delicious food.

b. *Irritating their dog ate delicious my food.

Interrogatives such as whose in whose books, what in what problems, and which in

which computer are determiners. Quantiers such as any, many, much, and all are usu-

ally considered determiners, e.g. in much work, many people, and all research. Some are

used before other determiners, namely, all, both, and half, as in (35). ese quantiers

are called pre-determiners, and abbreviated Pre-D. Finally, quantiers may be adjectival,

as in the many problems and in (36):

(35) All the books; half that man’s money; both those problems.

(36) e challenges are many/few.

Numerals are sometimes determiners, as in two books, and sometimes more like

adjecti ves, as in my two books. Table 2.4 shows the determiners in the order in which

they may appear. I have added the category adjective to the table since some of the

words that are clear determiners can also be adjectives. e categories are not always a

100% clear-cut, and (37) tries to shed some light on the dierence.

3. Believe it or not, Gucci and Coco are names of real dogs!

Chapter 2. Categories

Table 2.4. Determiners

Pre-D D Adj

quantier all, both

half

some, many, all, few(er)

any, much, no, every, less, etc.

many, few

article the, a

demonstrative that, this, those, these

possessive my, etc., NP’s

interrogative whose, what, which, etc.

numeral one, two, etc. one, two, etc.

(37) e Determiner-Adjective Rule

A Determiner points to the noun it goes with and who it belongs to;

An Adjective gives background information about the noun.

. Auxiliary (AUX)

is category will be dealt with in detail in Chapter 6. For now, it suces to say that, as

its name implies, the auxiliary verb functions to help another verb, but does not itself

contribute greatly to the meaning of the sentence.

Verbs such as have, be, and do can be lexical verbs or auxiliaries. In (38a), have

is a lexical verb because it has a meaning ‘to possess’ and occurs without any other

lexical verb. In (38b), on the other hand, have does not mean ‘possess’ or ‘hold’, but

contributes to the grammatical meaning of the sentence, namely past tense with pres-

ent relevance. It therefore is an auxiliary to the lexical verb worked. e same is true

for be in (39). In (39a), it is the only verb and therefore lexical; in (39b), it contributes

to the grammatical meaning emphasizing the continuous nature of the event. Lexical

and auxiliary uses of do are given in (40a) and (40b) respectively:

(38) a. I have a book in my hand.

b. I have worked here for 15 years.

(39) a. at man is a hard worker.

b. at reindeer may be working too hard.

(40) a. She did her homework.

b. She didn’t sleep at all.

Because auxiliaries help other verbs (except when they are main verbs as in (38)),

they cannot occur on their own. us, (41) is ungrammatical:

(41) *I must a book.

. Coordinator (C) and Complementizer (C)

In this section, we discuss two categories that join other words or phrases. Coordinators

are relatively simple and join similar categories or phrases. Complementizers introduce

subordinate clauses and look remarkably similar to prepositions and adverbs. We abbre-

viate both as C.

An Introduction to the Grammar of English

Coordinators such as and and or join two elements of the same kind, e.g. the

nouns in (42):

(42) Rigobertha and Pablo went to Madrid or Barcelona.

ey are also sometimes called coordinating conjunctions, as in Figure 2.1, but in this

book, we’ll use coordinator. ere are also two-part coordinators such as both … and,

either … or, and neither … nor.

Figure 2.1. Connecting sentences (Reprinted with the permission of Universal Press Syndicate. All

rights reserved)

Complementizers such as that, because, whether, if, and since join two clauses

where one clause is subordinate to the other (see Chapter 7 for more), as in (43). e

subordinate clause is indicated by means of brackets:

(43) Rigobertha and Pablo le [because Isabella was about to arrive].

ey are also called subordinating conjunctions or subordinators. We will use com-

plementizer. Like prepositions, coordinators and complementizers are invariable

in English (i.e. never have an ending), but complementizers introduce a new clause

whereas prepositions are connected to a noun. Some examples of complementizers

and some of their other functions (if they have them) are provided in Table 2.5.

Table 2.5. A few complementizers

C Example of C use Other use Example of other use

aer Aer she le, it rained. preposition aer him

as Fair as the moon is, it… degree adverb as nice

because (43) –

before Before it snowed, it rained. preposition before me

for I expect for you to do that. preposition for Santa

if If she wins, that will be great. –

so He was tired, so he went to sleep. adverb so tired

that I know that the earth is round. D that book

when I wonder when it will happen. adverb He le when?

while She played soccer, while he slept. noun A short while

Chapter 2. Categories

ere is a group of words, namely yet, however, nevertheless, therefore, and so, as in

(44), that connects one sentence to another:

(44) “you are anxious for a compliment, so I will tell you that you have improved her”.

(Jane Austen, Emma, Vol 1, Chap 8)

Some grammarians see these as complementizers; others see them as adverbs. With

the punctuation as in (44), the complementizer scenario is more obvious since so con-

nects the two sentences. However, so sometimes appears at the beginning of a sen-

tence, in which case it could be an adverb expressing the reason why something was

done. I leave it up to you to decide what to do with these. You may remember from

Section 1.2 that so can also be a degree adverb, as in so nice.

We can now formulate another rule, namely the one in (45):

(45) e Preposition-Complementizer-Adverb Rule

A Preposition introduces a noun (e.g. about the book);

a Complementizer introduces a sentence (e.g. because he le); and

an Adverb is on its own (e.g. She went out; and Unfortunatel y, she le).

ese categories are oen ambiguous in Modern English because prepositions and

adverbs can change to complementizers.

.

Pronouns

In this section, I discuss the dierent pronouns in English. Pronouns are a hybrid

category since they do not carry much lexical meaning but they can function on their

own, unlike articles and complementizers, which need something to follow them. is

makes them hard to classify as lexical or grammatical categories.

Personal pronouns, such as I, me, she, he and it, and reexive pronouns, such

as myself, yourself, and herself, are seen as grammatical categories by many (myself

included). e reason is that they don’t mean very much: they are used to refer to

phrases already mentioned. However, in this book, I label personal and reexive pro-

nouns the same way as nouns, since they function like full Noun Phrases as Subjects

and Objects (more on this in Chapter 4). us, a determiner such as the cannot stand

on its own, but she, as in (46) from Shakespeare, can:

(46) ‘Twere good she were spoken with,

For she may strew dangerous coniectures

in ill breeding minds. (Hamlet, IV, 5, 14)

Personal pronouns can be divided according to number into singular and plural and

according to person into rst, second, and third person. For example, I and me are rst

person singular, and we and us are rst person plural. e second person pronoun you

An Introduction to the Grammar of English

is used both as singular and as plural. ird person singular pronouns he/him, she/her,

and it are further divided according to gender; the third person plural pronouns are

they and them.