The State

of Fashion

2020

2

The State of Fashion 2020

The State

of Fashion

2020

4

The State of Fashion 2020

CONTENTS

Executive Summary 1011

Industry Outlook 1215

Global Economy 1831

01: On High Alert 19

02: Beyond China 23

Southeast Asia: A Region of Nuanced Opportunity 26

Russia: Signs of Resurgence in a Polarised Market 28

The GCC: A Region in Transition 30

Consumer Shifts 3259

03: Next Gen Social 33

Want to See the Future of Social Media? Look to Asia. 37

04: In The Neighbourhood 43

Executive Interview: Pete Nordstrom 46

Unlocking the Power of Stores 50

05: Sustainability First 52

The Future of Upcycling: From Rags to Riches 56

Fashion System 6087

06: Materials Revolution 61

Fashion’s Biological Revolution 64

07: Inclusive Culture 66

Executive Interview: Annie Wu 70

08: Cross-Border Challengers 73

Executive Interview: Wang Mingqiang 76

09: Unconventional Conventions 79

Executive Interview: Raaello Napoleone 82

10: Digital Recalibration 85

McKinsey Global Fashion Index 8899

Glossary and Detailed Infographics 100

End Notes 102

MGFI

GLOBAL

ECONOMY

CONSUMER

SHIFTS

FASHION

SYSTEM

6

The State of Fashion 2020

7

For the fourth year in a row, The Business

of Fashion and McKinsey & Company have teamed

up to bring our trademark rigour and evidence to

debates within the global fashion industry and

to provide an authoritative annual picture of The

State of Fashion. This is now a knowledge base that

we build on every year, identifying the key themes

and business imperatives shaping the industry

while tracking the ways in which fluctuations in

the world economy feed through into fashion.

And this coming year — perhaps more so

than any year since we started — will see fluctua-

tions in abundance. Our first report was written in

the aftermath of the Brexit vote and went to press

the morning after Donald Trump had been elected

president of the United States. The unfolding

implications of both of these events continue to

impact the fashion market.

The year ahead will open with the industry

in a state of high nervousness and uncertainty,

with most executives across fashion and the wider

business world bracing for a slowdown in growth

in the global economy. Because fashion is a global

business with global supply chains, industry

players are anxious about the impact of taris and

trade disputes. And in terms of digitisation and

sustainability, the fashion industry is still playing

catch-up as the challenges in these areas become

more complex. Facing these interlinked hurdles

means that not everyone can win. The battle for

resources and talent continues to make it ever

tougher for many mid-sized and smaller brands

to compete.

So how to navigate these choppy waters?

Once again our global experts bring clarity to a

fragmented landscape of categories and segments,

countries and companies by establishing a

common understanding of the forces at work

in fashion. This report sets out how well we are

performing and identifies the top priorities, both

business and creative, for 2020. Through BoF’s

extensive expertise in fashion strengthened by

global industry networks, we thread McKinsey’s

international perspective and analytical rigour.

We then bolster this with our survey of over 290

global fashion executives (more than ever before)

and interviews with thought leaders and pioneers.

The report also includes the fourth readout of

our industry benchmark, the McKinsey Global

Fashion Index (MGFI): its extensive database of

companies allows us to analyse and compare the

performance of individual companies against

their peers, by category, segment or region.

Four years in, this is growing to become an

unrivalled resource.

Yet, while the coming year brings with it a

lot of uncertainty, exciting opportunities remain

for those who can make sense of the noise and

drive innovation accordingly. Whatever your

interest in the industry — from silent investor to

concerned consumer — this report tells you all you

need to know about the state of fashion in 2020.

— Achim Berg & Imran Amed

FOREWORD

Thomas Lohr

8

The State of Fashion 2020

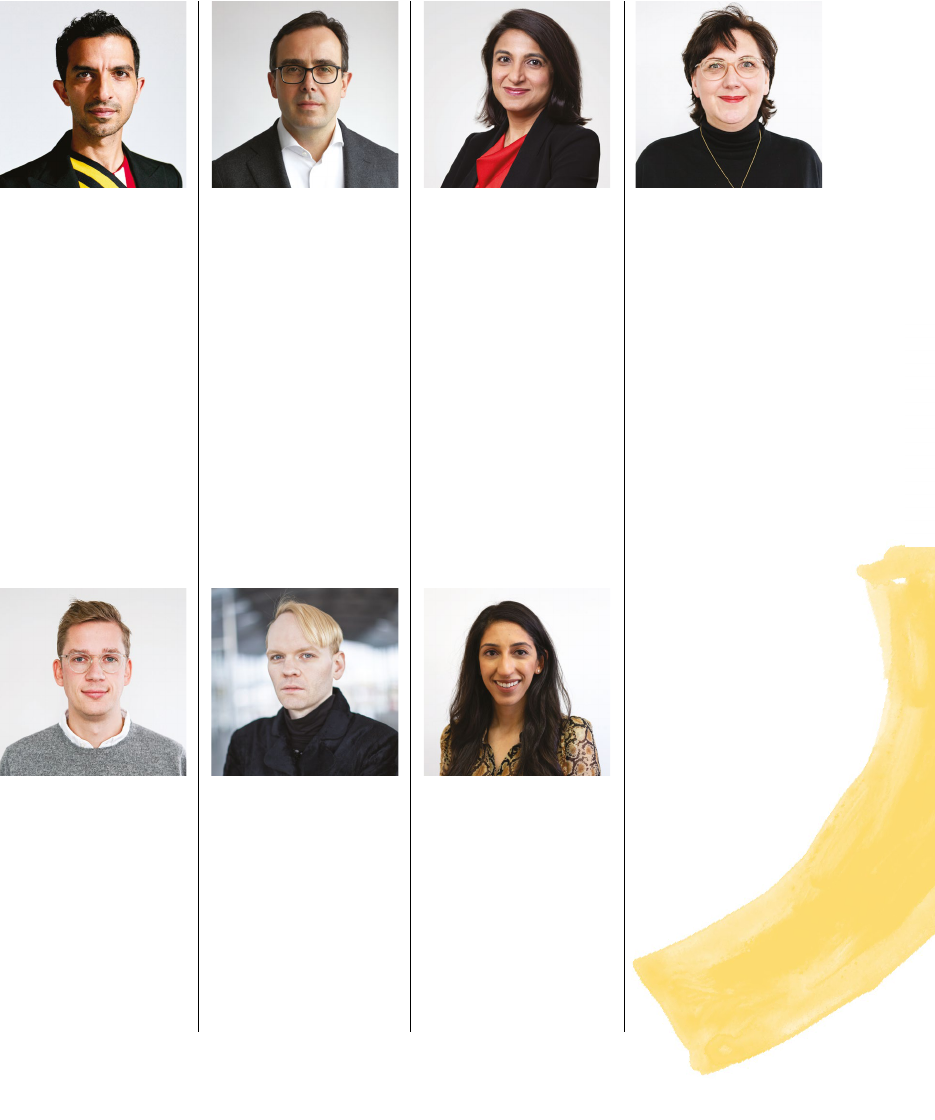

CONTRIBUTORS

ACHIM BERG

Based in Frankfurt, Achim

Berg leads McKinsey’s Global

Apparel, Fashion & Luxury

group and is active in all

relevant sectors including

clothing, textiles, footwear,

athletic wear, beauty,

accessories and retailers

spanning from the value end

to luxury. As a global fashion

industry and retail expert,

he supports clients on a broad

range of strategic and top

management topics, as well as

on operations and sourc-

ing-related issues.

IMRAN AMED

As founder, editor-in-chief

and chief executive of

The Business of Fashion,

Imran Amed is one of the

fashion industry’s leading

writers, thinkers and

commentators. Fascinated by

the industry’s potent blend

of creativity and business,

he began BoF as a blog in

2007, which has since grown

into the pre-eminent global

fashion industry resource

serving a five-million-strong

community from over 190

countries and territories.

Previously, he was a

consultant at McKinsey

in London.

SASKIA HEDRICH

As global senior expert

in McKinsey’s Apparel,

Fashion & Luxury group,

Saskia Hedrich works with

fashion companies around

the world on strategy,

sourcing optimisation,

merchandising transfor-

mation, and sustainability

topics — all topics she is also

publishing about regularly.

Additionally, she is involved

in developing strategies for

national garment industries

across Africa, Asia, and Latin

America.

FELIX RÖLKENS

Felix Rölkens is part of the

leadership of McKinsey’s

Apparel, Fashion & Luxury

group and works with

apparel, sportswear, and pure

play fashion e-commerce

companies in Europe and

North America, on a wide

range of topics including

strategy, operating model

and merchandising

transformations.

ANITA BALCHANDANI

Anita Balchandani is a

Partner in McKinsey’s

London oce, and leads the

Apparel, Fashion & Luxury

group in the United Kingdom.

Her expertise extends

across fashion, health and

beauty, specialty retail and

e-commerce. She focuses

on supporting clients in

developing their strategic

responses to the disruptions

shaping the retail industry

and in delivering customer

and brand-led growth

transformations.

ROBB YOUNG

As global markets editor of

The Business of Fashion,

Robb Young oversees content

from Asia-Pacific, the Middle

East, Latin America, Africa,

the CIS and Eastern Europe.

He is an expert on emerging

and frontier markets, whose

career as a fashion editor,

business journalist, author

and strategic consultant

has seen him lead industry

projects around the world.

SHRINA POOJARA

Shrina Poojara is a consultant

in McKinsey’s London oce,

specialising in Apparel,

Fashion and Luxury. She has

supported apparel and beauty

companies in the UK and

Europe, on topics including

strategy and mergers and

acquisitions.

9

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all members of The Business of Fashion and the McKinsey community for their contribution to the

research and participation in our State of Fashion Survey, and the many industry experts who generously shared their perspectives

during interviews. In particular, we would like to thank: Alex Kremer, Alexander Taylor, Annie Wu, Arnold Ma, Christoph

Barchewitz, Elijah Whaley, Georoy van Raemdonck, Graeme Raeburn, Hiromi Yamaguchi, Kavin Bharti Mittal, Lidewij Edelkoort,

Michael Sadowski, Nina Marenzi, Pete Nordstrom, Pierre Poignant, Rafaello Napoleone, Sarah Needham, Simon Lock, Stefano

Martinetto, Wang Minqiang, Yash Mehta.

The wider BoF team has also played an instrumental role in creating this report — in particular Amanda Dargan, Anouk Vlahovic,

Casey Hall, Cheryl Wischhover, Christina Yao, Kate Vartan, Lauren Sherman, Mary Catherine Nanda, Michael Edelmann, Niamh

Coombes, Nick Blunden, Olivia Howland, Queennie Yang, Rachel Strugatz, Sarah del Corral, Sarah Kent, Venetia van Hoorn Alkema,

Victoria Berezhna, Vikram Alexei Kansara, Zoe Suen.

The authors would like to thank Marilena Schmich and Tiany Chan from McKinsey’s Berlin and Dallas oces respectively for

their critical roles in delivering this report. We also acknowledge the following McKinsey colleagues for their special contributions

to the report creation and in-depth articles: Aimee Kim, Alex Sukharevsky, Alexander Dobrakovsky, Ali Potia, Alice Zheng, Anneke

Maxi Pethö-Schramm, Dale Kim, Denis Emelyantsev, Gerry Hough, Karl-Hendrik Magnus, Laura Gallagher, Maliha Khan, Martins

Mellens, Matthias Evers, Michael Chui, Nitasha Walia, Patrick Guggenberger, Sergio Velasquez-Terjesen, Shani Wijetilaka, Simon

Wintels, Thirumagal B and Tyler Harris. We also appreciate the support we have received from other McKinsey colleagues across

the globe: Adhiraj Chand, Alastair Macaulay, Althea Peng, Andres Avila, Anita Liao, Ankita Das, Antonio Achille, Antonio Gonzalo,

Cherry Chen, Claire Gu, Colleen Baum, Colin Henry, Damian Hattingh, Daniel Zipser, Emily Gerstell, Ewa Sikora, Fernanda Hoefel,

Heloisa Callegaro, Holly Briedis, Jean-Baptiste Coumau, Jennifer Schmidt, Jihye Lee, Kanika Kalra, Kapil Joshi, Karsten Lafrenz,

Marie Strawczynski, Martine Drageset, Matthias Heinz, Nicola Montenegri, Oliver Ehrlich, Peter Stumpner, Raj Shah, Ray Liu,

Rebeca Vega, Sara Kappelmark, Sophie Marchessou, Susan Nolen Foushee, Thomas Tochtermann, Tom Skiles, Vorah Shin, and

Younghoon Kang. We’d also thank David Honigmann, David Wigan and Jonathan Turton for their editorial support, and Adriana

Clemens for external relations and communications.

In addition, the authors would like to thank Joanna Zawadzka for her creative input and direction into this State of Fashion report,

Ellen Rutt for the cover illustration and Getty Images for supplying imagery to bring the findings to life.

10

The State of Fashion 2020

Fashion leaders are not looking forward to

2020. The prevailing mood among respondents to

our executive survey is one of anxiety and concern.

In contrast to last year, when there were pockets

of optimism in North America and within the

luxury segment, we now see pessimism across all

geographies and price points. To make matters

more complicated, although we know that external

shocks will continue, we don’t know what form

they will take.

Even without the economic headwinds,

these would be challenging times. The McKinsey

Global Fashion Index (MGFI) forecasts that global

fashion industry growth will slow further — down

to 3 to 4 percent — slightly below predicted growth

for 2019. Fashion players are under pressure to be

digital-first and fully leverage new technologies,

to improve diversity across their assortments and

organisations and to address growing demand

for the industry to face the sustainability agenda

head-on.

Yet not all companies are created equal.

Polarisation persists and the “Super Winners” —

the top 20 players by economic profit — account

In Troubled Times,

Fortune Favours the

Big and the Bold

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

11

for more than the combined economic profit of the

entire industry. Not only are they highly value-cre-

ating and of immense scale, but they often pioneer

innovation in the industry through their product

ranges and interaction with consumers. They

are also best positioned to attract the industry’s

limited resources and talent, while others risk

getting left behind. A growing proportion of

publicly traded fashion companies are actually

“value destroyers” that rack-up negative economic

profit. In a “winner takes all” market, the implica-

tions for laggards are troubling.

Volatility is here to stay, so fashion

companies should take steps to become more

resilient, build a profound understanding of the

risks they face and consider strategic actions to

minimise them. Successful companies will be the

ones that make moves early, focus on boosting

earnings over revenue growth, and work out how to

improve productivity while ensuring operational

and financial flexibility. Crucially, all this will

require leaders who make quick decisions in an

environment of great uncertainty.

The good news is that for companies that do

display resilience and resolve, additional rewards

are there for the taking beyond 2020. While China

continues to present a lucrative opportunity

for many global and local fashion players, some

companies are at risk of becoming over-reliant on

the market. We see further potential to explore

markets beyond China, including India, Southeast

Asia, the Middle East and Russia.

To better address consumer themes next

year, fashion players should focus on clearly

understanding how to best use new social media

channels and functions, how to optimise their

store networks and experience, and how to best

deliver industry change toward greater sustain-

ability. Both R&D and innovation will play vital

roles in delivering short-term sustainability

targets and in reinventing fashion’s economic

model for longer term transformation. Consumers

and employees will continue to demand more from

purpose-driven companies that champion their

values — from climate change consciousness to

diversity and inclusion.

Nonetheless, threats remain for

incumbents across the industry who don’t

respond or adapt fast enough. Facilitated by

e-commerce marketplaces linking them direct

to global consumers, Asian players will intensify

their competition with western brands through

cross-border channels. Meanwhile, digital pure

players that pioneer new business models may

prove exciting as new paths to profitability emerge,

but other tech players will begin to falter. And as

industry-wide digitisation progresses, the need

for reinvention has even reached showrooms and

trade fairs.

While 2020 is not expected to be easy, it

will be significantly more challenging for some

companies than for others. Indeed, the year

ahead will require fashion companies to deliver

meaningful change across the value chain and on

multiple fronts while mitigating risk and managing

uncertainty. But, for the fortunate few, there will

also be opportunities to capture.

Executive Summary

Successful companies will

be the ones that make moves

early, focus on boosting earnings

over revenue growth, and work

out how to improve productivity

while ensuring operational and

inancial lexibility.

12

The State of Fashion 2020

The fashion industry faces a worrying year

ahead. The macroeconomic context is challenging,

and players will find that their route to value

creation is either unclear or it requires levels of

investment that are hard to swallow. Digitisation

remains critical, while players must address

increasing consumer concerns over sustainability,

if they want to secure their future.

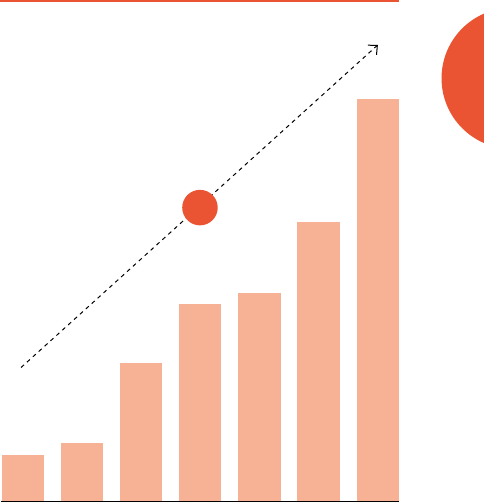

Overall, the McKinsey Global Fashion

Index predicts that the fashion industry will

continue to grow at 3 to 4 percent in 2020, slightly

slower than the 3.5 to 4.5 percent estimate for

2019 (see Exhibit 19). This slowdown will stem

from consumers being increasingly cautious amid

broader macroeconomic uncertainty, political

upheaval across the globe and the continued threat

of trade wars. This year has already been tough,

and economic gains continue to flow to a select

small group of players, while the middle is increas-

ingly squeezed and the share of companies actively

destroying value grows.

In North America, consumer sentiment is

muted and taris — aided by the strengthening

dollar — are impacting both imports and exports.

Emerging Asia-Pacific markets are still relatively

strong although growth is slowing: retail sales

in the region have been falling short of expecta-

tions, and will continue to disappoint in 2020 as

consumer sentiment weakens. On the other side of

the world, mature Europe continues to suer from

the general global economic malaise and ongoing

uncertainty around Brexit. Growth in emerging

Europe, Latin America, the Middle East and Africa

is expected to remain stable overall with some

brighter spots, such as Brazil and Nigeria — two of

the most populous nations in the world that have

rapidly expanding middle classes.

Naturally, this uncertainty is reflected in

our annual BoF-McKinsey senior executive survey.

Strikingly, only 9 percent of respondents think

conditions for the industry will improve next year,

compared to 49 percent who said the same last

year. “Challenging,” “uncertain” and “disruptive”

were the most frequently used words to describe

the industry compared to last year’s more

neutral “changing,” “digital” and “fast.” Another

divergence from previous years is that now

pessimism holds broadly true regardless of region

or segment, with more than half of respondents

The Glaring Gap Between

the Best and the Rest

The most optimistic region is

Asia, although, even here only 14

percent of executives expect an

improvement in conditions.

INDUSTRY OUTLOOK

13

Exhibit 1:

The majority of fashion executives across value segments and geographies

foresee a slowdown in the industry in 2020

% OF FASHION EXECUTIVE RESPONDENTS, EXPECTATIONS FOR 2020 ECONOMIC CONDITIONS RELATIVE TO 2019

Exhibit 2:

The economic backdrop, the evolution of digital oerings and younger

consumers’ passion for causes are front of mind for executives

% OF RESPONDENTS THAT RATED EACH THEME AS ONE OF THE TOP THREE IMPACTING THEIR BUSINESS IN 2019

SOURCE: BOFMCKINSEY STATE OF FASHION 2020 SURVEY

SOURCE: BOFMCKINSEY STATE OF FASHION 2020 SURVEY

Premium/luxury

Mid-market

Value

North America

Europe

Asia

BY SEGMENT

BY GEOGRAPHY

Worse Same Better

57

58

58

31

39

38

12

3

4

61

55

59

30

38

27

9

7

14

Caution Ahead

Digital Landgrab

Getting Woke

Self-Disrupt

Now or Never

Trade 2.0

Radical Transparency

On Demand

End of Ownership

Indian Ascent

50

49

44

43

36

34

16

15

12

4

14

The State of Fashion 2020

in every region predicting a deteriorating

environment. The most optimistic region is Asia,

although, even here only 14 percent of executives

expect an improvement in conditions. And in

luxury, where performance has been strong, there

is still little hope of an upturn.

We also asked survey respondents three

questions to probe what was at the top of their

personal agenda: which of the themes predicted in

last year’s State of Fashion report were in the top

three impacting their business today; what do they

see as the biggest challenges facing the industry

going forwards; and what do they consider to be the

biggest opportunities for next year? Their answers

reveal some consistent themes.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, concern about

the global economy was both a key topic from last

year’s themes and ranked second and third in the

challenges facing the industry next year. Beyond

the economic context, the digitally-focused

themes “Digital Landgrab” and “Now Or Never”

both resonated most with global industry leaders

— there is no doubt that digital remains at the

forefront of executives’ minds. The word itself

was the fourth most popular to describe the

industry, while digitisation was listed as one of

the top three opportunities.

For the first time, sustainability topped the

list of the biggest challenges facing the industry,

and it was also named the biggest opportunity;

the rise of Extinction Rebellion and the demon-

strated ability of Greta Thunberg to mobilise

her generation make this ever-more relevant.

While the sustainability-related theme, “End of

Ownership,” was seen by our respondents overall

as less salient, we believe it may not yet have

reached critical mass and will continue to rise

in importance. Indeed, the theme is becoming

increasingly dynamic as fashion players at the

forefront experiment with opportunities to

prolong the lifespan of clothes — we expect more

to follow suit.

Last year we predicted a “unicorn” in this

space — in fact, Rent the Runway and StockX both

duly topped billion dollar valuations earlier this

year, joining The RealReal, which in turn went

public in 2019. The shift from a focus on generating

value for shareholders to companies becoming

purpose-led more broadly is reflected in the

importance attached in part to last year’s “Getting

Woke” theme, which suggested that consumer

demand for “wokewear” would have a major impact

on fashion players.

Alongside sustainability and digitisation,

the third major opportunity for the industry next

year, as cited by our survey respondents, was

innovation. No wonder then, given the investment

needed to meet these challenges, that small and

medium-sized players are particularly nervous

about what lies ahead. This is particularly acute in

luxury, where the world’s biggest groups continue

to increase their market share.

Our ten defining themes for 2020 are a

sharp evolution from previous years, with the

risks closer at hand and more severe. What is clear

is that setting a course through the turbulence

ahead, now more than ever, requires companies to

be attuned to their environment and agile in their

responses. While the winners at the top maintain

their industry dominance, the rest will have to

work even harder to keep pace.

What is clear is that setting a

course through the turbulence

ahead, now more than ever,

requires companies to be attuned

to their environment and agile in

their responses.

Industry Outlook

15

16

The State of Fashion 2020

01.

On High Alert

Continued caution

is advised for the

year ahead as

mounting underlying

turmoil could disrupt

relations among

both developed and

emerging market

economies. Indicators

of recession risk are

spurring companies

across industries

to build a resiliency

playbook and plan

for other macro risks

such as geopolitical

instability and the

inlammation of trade

tensions.

02.

Beyond China

China will continue

to provide exciting

opportunities and

play a leading role

in the global fashion

industry, but the

colossal market is

proving harder to

crack than brands

anticipated. As some

successful players

become over-reliant

on China and others

struggle, companies

should consider

spreading their risk

by expanding to

other high-growth

geographies.

04.

In the

Neighbourhood

Consumer demand

for convenience

and immediacy is

prompting retailers

to complement

existing brick-and-

mortar networks with

smaller format stores

that meet customers

wherever they are and

reduce friction in the

customer journey.

The winning formula

will feature in-store

experiences and

localised assortments

in neighbourhoods

and suburbs beyond

the main shopping

thoroughfares.

03.

Next Gen

Social

As traditional

engagement

models struggle on

established social

media platforms,

fashion players will

need to rethink their

strategy and ind

ways to maximise

their return on

marketing spend.

Attention-grabbing

content will be key,

deployed on the

right platform for

each market, using

persuasive calls-to-

action and, wherever

possible, a seamless

link to checkout.

05.

Sustainability

First

The global fashion

industry is extremely

energy-consuming,

polluting and wasteful.

Despite some modest

progress, fashion

hasn’t yet taken

its environmental

responsibilities

seriously enough.

Next year, fashion

players need to

swap platitudes and

promotional noise for

meaningful action and

regulatory compliance

while facing up to

consumer demand

for transformational

change.

GLOBAL ECONOMY

The percentage of

survey respondents that

expect global economic

conditions to improve in

the next year has fallen

from 49 percent for 2019

to 9 percent for 2020

More than half of fashion

executives believe a

“localised brick-and-

mortar-experience” will

be a top theme in the

coming year

More than two-thirds of

fashion players believe

“increased exploration

of spend on new media

platforms vs. ‘traditional’

platforms” will be a top

theme in the coming year

The population of

consumers aged 30 or

below in ive identiied

exciting markets

outside of China will

grow to be more than

double that of China

by 2025

Survey respondents

stated that “sustainability”

will be both the single

biggest challenge

and the single biggest

opportunity for the

industry in 2020

55%

The State of Fashion 2020

CONSUMER SHIFTS

49

2019 2020 2025 Forecast

9

2.3x

70

%

17

The State of Fashion 2020

08.

Cross-Border

Challengers

Established fashion

brands and retailers

will face growing

competition from new

Asian challengers,

as manufacturers

and SMEs step out of

their traditional roles

and sell directly to

global consumers.

Expect greater

competition from

hitherto unknown

players in the Asian

supply chain who

design popular items

to sell at aordable

prices using cross-

border e-commerce

platforms.

09.

Unconventional

Conventions

Traditional trade

shows must respond

to the increase of

direct-to-consumer

activity, shorter fashion

cycles and digitisation

by embracing new

roles and ine-tuning

their target audience.

In a bid to dierentiate

themselves — or even

just to survive — more

of these events will

add B2C attractions or

launch new services

and experiences to

improve relationships

with their traditional

B2B audience.

10.

Digital

Recalibration

Valuations of digital

fashion players have

reached dizzying

levels and, despite a

slew of high-proile

IPOs and private

irms achieving

unicorn status,

investor sentiment

is taking a turn for

the worse. Investor

apprehension is

growing over the

path to proitability

for some digital

players, from online

pure play retailers

and marketplaces,

to direct-to-consumer

brands and other

digital-irst business

models.

06.

Materials

Revolution

Fashion brands are

exploring alternatives

to today’s standard

materials, with key

players focused on

more sustainable

substitutes that

include recently

rediscovered and

re-engineered

old favourites as

well as high-tech

materials that deliver

on aesthetics and

function. We expect

R&D to increasingly

focus on materials

science for new

ibres, textiles,

inishes and other

material innovations

to be used at scale.

07.

Inclusive

Culture

Consumers and

employees are putting

increasing pressure

on fashion companies

to become proactive

advocates of diversity

and inclusion.

More companies

will elevate diversity

and inclusion as

a higher priority,

embed it across

the organisation

and hire dedicated

leadership roles, but

companies’ initiatives

will also come under

increasing scrutiny

in terms of sincerity

and results.

Across fashion

companies there

are seven male chief

executives for every one

female chief executive

The percentage of

respondents that

think using innovative

sustainable materials

is important for their

company

The average fashion-

tech IPO of the past two

years has seen a 27%

decrease in its stock

price since going public

The trade show of the

future will need to be

highly digital, rethink its

target audience and bring

fresh trends and ideas

from the industry to the

forefront

Year-on-year growth in

APAC cross-border B2C

e-commerce transaction

value is 37 percent

-27%

FASHION SYSTEM

37%

67%

18

The State of Fashion 2020

GLOBAL

ECONOMY

19

01. ON HIGH ALERT

Continued caution is advised for the year ahead as

mounting underlying turmoil could disrupt relations

among both developed and emerging market economies.

Indicators of recession risk are spurring companies

across industries to build a resiliency playbook and to

plan for other macro risks such as geopolitical instability

and the inlammation of trade tensions.

The global economy is under pressure, with

political and geopolitical instability complicating

the outlook for the global fashion industry in 2020.

But this uncertainty is not limited to fashion.

Executives from across industries are increas-

ingly pessimistic, and central banks around the

world are taking action and loosening monetary

policy. Against this gloomy backdrop, the fashion

industry is already facing major challenges,

from sustainability issues to generational shifts,

many of which require investment at a time when

top-line revenues are potentially under threat.

In 2020, fashion players will need to ensure they

are suitably resilient — driving productivity gains

while creating operational flexibility, digitising

where most appropriate, divesting non-core assets

to free up cash, and carefully monitoring and

managing a wide range of risks.

Last year, we reported on the deteriorating

outlook for the global economy. Since then, the

situation has only worsened. No surprise then that

55 percent of respondents in the BoF-McKinsey

annual executive survey expect conditions for the

industry to worsen in the next year, up consid-

erably from 42 percent last year. And of those

55 percent, half expect conditions to be “much”

worse, compared to just a handful of respondents

last year.

Trade tensions and Brexit continue to

create significant uncertainty and are having a

quantifiable impact on growth. The US-China

trade war has led to billions of dollars of taris

being imposed on imported goods between the two

countries, with knock on implications around the

globe. The IMF stated in July that reducing trade

tensions and resolving uncertainty around trade

agreements is a vital part of putting global growth

on a stronger footing.

1

The overall numbers are bleak. The WTO

more than halved its global trade volume growth

forecast for 2019 to 1.2 percent and warned that

the 2.7 percent growth it predicts for 2020

is still dependent on a return to “more normal

trade relations.”

2

Every region faces challenges. In Europe,

the UK service sector contracted in September,

while the annualised output of the German

economy was the lowest in six years. Meanwhile,

Chinese GDP growth slowed to 6 percent in the

55 percent of respondents in the

BoFMcKinsey annual executive

survey expect conditions for the

industry to worsen in the next year.

20

The State of Fashion 2020

Global Economy

third quarter of this year, and September’s export

figures were 3.2 percent lower than a year earlier,

and nearly 22 percent lower to the US.

3

In the US, service-sector growth hit a

three-year low at the start of October and for

the first time since the financial crisis, yields on

short-term US bonds eclipsed long-term bond

yields in August, a closely followed recession

indicator, which suggested investors were

scrambling for safer assets.

Japan’s exports have been falling every

month since the start of the year, Brazil’s

government halved its growth forecast for 2019

to just 0.8 percent in July, and India’s economy is

growing at its slowest pace in the past six years.

Faced with this synchronised global

downturn, central banks from the US to Australia

are cutting interest rates, and the European

Central Bank announced its biggest stimulus

package in three years. In China, the People’s

Bank cut its reserve requirement ratio (the amount

cash lenders must retain on their balance sheets)

for the third time this year in an attempt to

stimulate growth.

Business leaders are understandably wary.

In just six months, the number of executives who

think the global economy will shrink has risen

from less than half to over two-thirds. Three-

quarters think global economic conditions are

worse than six months ago and three-quarters

rank trade conflicts as one of the biggest risks to

global economic growth over the next year.

4

These concerns are already aecting

business decisions. In October, WTO Director-

General Roberto Azevêdo said, “Trade conflicts

heighten uncertainty, which is leading some

businesses to delay… productivity-enhancing

investments.”

5

In the UK, Bank of England

research showed that uncertainty over leaving the

EU has reduced capital spending on average by

about 11 percent,

6

while the number of companies

including Brexit warnings in their annual report

has more than doubled in the past six months.

7

Political upheavals in regions from Asia to

Latin America are adding to the uncertainty and

pessimism. The long-running protests in Hong

Kong have had a significant impact on the economy,

with Greater China retail sales significantly

missing estimates and tourism from mainland

China down 42 percent. Elsewhere, tensions in the

Middle East and attacks on oil plants are aecting

oil prices, which can have a major ripple eect

around the world.

The fashion industry must tackle these

existential challenges at a time when it faces

significant internal issues of its own. The drive for

sustainability is pushing many to rethink business

models and move towards more responsible

business practices. Customers’ demand for new and

enhanced services is driving brands and retailers

to invest heavily to meet these needs even at a time

when more than half of fashion executives feel they

do not suciently understand Generation Z — now

the largest global customer cohort.

The strain is starting to show. In

September, vacancies in US shopping malls hit

an eight-year high, with Sears, Victoria’s Secret

and Charlotte Russe among the household names

shutting outlets across the country. In the same

month, Forever 21 joined a growing list of brick-

and-mortar players who have filed for bankruptcy

across dierent markets including Debenhams,

the US arms of Roberto Cavalli and Diesel, and

department store Barneys New York. Retail is

the only sector in the US that has seen net job

Japan’s exports have been falling

every month since the start of the

year, Brazil’s government halved

its growth forecast for 2019 to

just 0.8 percent in July, and India’s

economy is growing at its slowest

pace in the past six years.

21

losses over the past two years, while in the UK,

high street store closures are the highest since

monitoring began in 2010.

8

In Europe, Moody’s

expects more than 40 percent of the retailers it

rates to record lower profits in 2019 than in either

of the previous two years.

9

Even in China, clothing

sales fell in April for the first time since 2009.

10

Given the worrying outlook we expect

fashion companies to take steps to become more

resilient in 2020. The first step is to develop a deep

understanding of the risks they face. These can

be codified in a “risk register” that dierentiates

between day-to-day risks, external disruptions

(e.g., supply-chain interruptions, trade disputes),

and disruptive strategic risks (e.g., remaining

relevant amid changing consumer preferences or

competing with challengers using new business

models). Both the impact, likelihood and prioriti-

sation of these risks will vary over time, so the risk

register needs to be a dynamic document.

There are also lessons to be learned from

previous economic crises. McKinsey’s analysis of

companies that outperformed their peers during

the last downturn showed that they made moves

early and focused on earnings over revenue. By the

time the downturn reached its 2009 trough, the

EBITDA of these resilient players had risen by 10

percent, while their industry peers had lost nearly

15 percent.

11

Throughout the year ahead, fashion

companies should remain on high alert. The most

forward-thinking players will therefore also

develop a resilience playbook to ensure they are

prepared. This is likely to involve plans to boost

productivity while ensuring operational flexibility

(e.g., using variable contracts and more diverse

supply sources), a clear approach to digitisation

and a sharp focus on financial flexibility. This

means divesting non-core and under-performing

assets early so that the company has the cash on

hand to make strategic investments as soon as the

economic outlook improves — when their peers

might be shedding assets. Crucially, all this will

require enhanced leadership to be able to make

quick decisions amid a high degree of uncertainty.

Throughout the year ahead,

fashion companies should remain

on high alert. The most forward-

thinking players will therefore

develop a resilience playbook to

ensure they are prepared.

01. On High Alert

Exhibit 3:

Executives are becoming

increasingly pessimistic about

global economic growth

GLOBAL ECONOMIC GROWTH EXPECTATIONS FOR THE

NEXT SIX MONTHS, % OF EXECUTIVE RESPONDENTS

1

SEP 2018 MAR 2019 SEP 2019

1

RESPONDENTS WHO ANSWERED “DON’T KNOW” WERE REMOVED FROM

SAMPLE. TOTALS MAY NOT ADD TO 100 DUE TO ROUNDING

SOURCE: ECONOMIC CONDITIONS SNAPSHOT, SEPTEMBER 2019, MCKINSEY

GLOBAL SURVEY RESULTS

Increase

No change

Contract

39

44

67

44

34

15

16

21

17

22

The State of Fashion 2020

23

Fashion brands have long targeted China

as an outstanding growth opportunity. And rightly

so. Over the past 10 years, China accounted for 38

percent of global fashion industry growth across

segments.

12

Since 2012 it has been responsible

for an impressive 70 percent of expansion in the

luxury segment, and we expect this dominance to

continue out to 2025.

Indeed, some brands have been very

successful in China. Luxury players such as LVMH

and Gucci have already been in the market for

years, having first opened stores in the 1990s.

13

Both continue to see positive results; LVMH

saw “unheard of growth rates” in 2019, while

in February, Kering defied market concerns of

a China slowdown in luxury, with Jean-Marc

Duplaix, the group’s financial director, high-

lighting the “dynamic” sales from their Chinese

clientele.

14 15

Other international brands also

continue to perform well — Lululemon grew

China revenues by 68 percent in the second

quarter of 2019, while Nike and Uniqlo reported

strong demand.

16

Mass-market players have also

prioritised China as a core part of their business

models; China now accounts for 5 percent of

H&M’s global revenues,

17

while Inditex has over

600 stores across the country, making up over

8 percent of its store network.

18

Still, not everyone has been so successful.

Asos and New Look are recent examples among

those to have retreated. Dolce & Gabbana and

Burberry are among players that have been in

the press due to advertising campaigns that

mismatched the sentiment of Chinese consumers.

Some international mass-market brands

have struggled to compete against established

Chinese brick-and-mortar players, some of which

have thousands of outlets. Physical retail still

plays an important role — 85 percent of shoppers

engage with both online and oine touchpoints,

compared with 80 percent in 2017.

19

Local Chinese

high-street brands such as Urban Revivo and

Peacebird have been growing at pace in the region,

ramping up competition for foreign brands.

The bottom line? The path to success

in China can be elusive. Nonetheless, despite a

slowdown of economic growth, the ocial growth

forecast of 6 percent to 6.5 percent for 2019 is still

02. BEYOND CHINA

China will continue to provide exciting opportunities and

play a leading role in the global fashion industry, but the

colossal market is proving harder to crack than brands

anticipated. As some successful players become over-

reliant on China and others struggle, companies should

consider spreading their risk by expanding to other high-

growth geographies.

A pedestrian at the Trang Tien Plaza luxury shopping centre in Hanoi, Vietnam. Maika Elan/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Physical retail still plays an

important role — 85 percent of

shoppers engage with both online

and oline touchpoints, compared

with 80 percent in 2017.

24

The State of Fashion 2020

among the highest of major global economies, and

the region this year (2019) overtook the US as the

largest fashion market in the world.

20

Consumer-

driven consumption is still fast growing, in

a country that adds absolute gross domestic

product (GDP) equivalent to that of the entirety of

Australia to its economy each year. Furthermore,

as incomes rise, Chinese consumers show a strong

propensity to trade up, which on the whole is good

news for upmarket foreign brands. Yet, winning in

China cannot be the sole focus, and it makes sense

for brands to direct at least some of their attention

toward other smaller, yet high growth markets.

India continues to present an exciting

opportunity, as we highlighted in last year’s

report (“Indian Ascent”), particularly for price

competitive players. While GDP growth this year

has been somewhat weaker than expected, in

part due to regulatory uncertainty, India is still

projected to be the fastest-growing major economy,

according to the IMF.

21

The Indian clothing market

will be worth $53.7 billion in 2020, making it the

sixth largest globally.

22

Notwithstanding the market’s challenges,

international players from H&M to Adidas are

engaging with India enthusiastically.

23

Internet

retailing accounted for nearly 11 percent of the

apparel market in 2018, double the proportion

just three years prior, driven in part by increasing

internet and smartphone penetration.

24

25

In fact,

India saw the strongest absolute growth globally

in the number of internet users in the past year.

26

Social media use is expanding at around 25 percent

annually, with nearly 70 percent of users active

on Instagram. This is providing a platform to

introduce consumers to fashion brands away from

the dominant informal market.

Southeast Asia also provides significant

opportunities; at nearly 270 million people,

Indonesia is the fourth largest country in the world

by population.

27

Vietnam and the Philippines are

seeing rapid GDP growth. Across Southeast Asia,

the median age is just 29, against 37 in China, high-

lighting the potential for growth as large numbers

of young people enter the workforce each year.

28

As in China, demand is being driven by digitally

native consumers, excited by the possibility of

creativity and self-expression. It is worth high-

lighting that these countries are highly diverse;

some consumers in the Philippines have a high

anity for western fashion trends, while Indonesia

is due to be the largest modest fashion market in

the world. Given the wide spectrum of taste within

each country and the dierences in regulation

between countries, each of these markets alone can

lend themselves as part of a considered expansion

strategy for success at scale. Equally, brands can

explore a regional approach to establish a toehold

and gain from the regional economy of scale.

Russia is an interesting proposition;

distracted by headlines about geopolitics in recent

years, the country’s fashion sector has remained

largely ignored by international fashion media.

Yet Russia’s clothing market is worth close to

$30 billion annually and is the ninth largest in

the world, according to data from McKinsey

FashionScope. Despite recent economic slowdown

in the country, the luxury market is showing new

signs of stabilisation. In 2018, LVMH, Dior and

Tiany all reported the highest sales in the region

since 2014.

29

An increasingly budget-conscious

middle class is creating new opportunities for

price competitive players. Russians have embraced

e-commerce too, which grew at an impressive 26

percent year-on-year in the first half of 2019.

30

The attractiveness of the country is also being

boosted by growing numbers of Chinese tourists,

who are expected to spend US $1.1 billion in Russia

in 2019.

31

Elsewhere, Brazil has been overlooked by

many in recent years, amid see-sawing economic

growth in the world’s sixth most populous

Global Economy

Indonesia is due to be the largest

modest fashion market in the world.

25

country.

32

Still, McKinsey’s 2019 Global Sentiment

Survey highlights increased confidence among

Brazilian consumers. Taris are a challenge

— Brazil has 23.3 percent taris for textiles,

according to the World Trade Organisation, but

there are still opportunities.

33

“More and more

international brands are looking to enter Brazil,”

says Christoph Barchewitz, co-chief executive of

emerging markets e-commerce platform Global

Fashion Group, which operates the Latin American

fashion e-commerce site Dafiti. “We recently

supported Ralph Lauren and Banana Republic

launching [digitally] into the market, and are

speaking to others.”

Finally, the Middle East still has potential,

despite being an already well-established fashion

market with a strong mall culture. While the Gulf

countries are far smaller than China in terms of

population size, the propensity of its shoppers to

spend big is what gives the region an outsized role

among international markets. In fact, the average

consumer in the UAE and Saudi Arabia respec-

tively spends over 6 times and 2 times as much

on fashion as the average consumer in China.

34

Some 99 percent of the UAE population uses social

media, underscoring the presence of a connected,

aspirational population craving style inspiration

and global fashion. The model in the Middle

East is dierent given historical restrictions on

foreign ownership: international fashion players

habitually partner with established and tried-and-

tested local players, the likes of whom have worked

with brands from Louis Vuitton to H&M for years.

These include Alshaya, Al Tayer and Chalhoub.

One largely untapped opportunity for overseas

brands to explore is how to better serve the region

in terms of e-commerce, given many franchisees

don’t own brands’ digital rights.

As fashion players continue to find the right

formula for China, other international markets

provide a rich seam of potential. That’s not to say

that China’s fashion market is nearing saturation.

Far from it. In 2020 we expect to see many

companies continuing to seize opportunities and

grapple with complexities there. Those that get it

right will prosper. But successful players

and struggling players alike will do well to

remember there are also opportunities elsewhere.

As fashion players put themselves to test in these

growth markets, they will have to strengthen their

brands and upgrade their operations to be able to

create value.

02. Beyond China

Exhibit 4:

There is a large market of young

consumers “Beyond China,” more

than double the size of that in China

POPULATION AGED 30 OR BELOW, MILLIONS

2025 FORECAST

CHINA

517

1,208

“BEYOND CHINA”

SOURCE: UNITED NATIONS, POPULATION DIVISION, WORLD POPULATION

PROSPECTS 2019

UAE & Saudi Arabia

Russia

Southeast Asia

Brazil India

2.3X

26

The State of Fashion 2020

Although luxury players continue to

expand or operate in most of the largest cities

in this diverse and dynamic region, there are

other opportunities for fashion players beyond

those serving the auent of Southeast Asia. An

emerging middle class experiencing rising levels

of disposable income is developing a taste for

fashion brands away from the informal market and

it is this demographic that is set to drive growth

in the region’s $50 billion apparel sector across

the six core markets — Vietnam, the Philippines,

Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and Singapore.

35

These markets are vibrant, increasingly

driven by young digitally sophisticated consumers.

Some 40 percent of the population is under the

age of 25, compared with 28 percent in China and

30 percent in the US.

36

Internet penetration is 63

percent, compared with 57 percent in China, and

social media use is growing fast; the number of

social media users in the region grew from 360

million to 402 million in just a year.

37

With young people spending increasing

amounts of time online, e-commerce is also

growing, albeit from a relatively low base. Within

the fashion sector, just 6 percent of 2018 retail

spend in the region was via e-commerce, as

opposed to China’s near-32 percent.

38

Still, the

three largest e-commerce players in the region

— Lazada, Shopee and Tokopedia — together saw

their gross merchandise value multiply seven

times between 2015 and 2018.

39

These players

boast international brands from Adidas and

Levi’s, to The Body Shop and Maybelline, echoing

Taobao’s path in China.

While there are similarities across these

Southeast Asian markets that sit within the

ASEAN trade bloc and thus operate on principles

of intra-regional free trade, there are also

significant dierences, in part due to regulation

and local tastes. Vietnam, for example, recently

signed a new trade agreement (EVFTA) with the

EU and boasts the highest levels of foreign direct

investment in the region. Thailand is encouraging

foreign investment with tax breaks, aiming to take

advantage of the recent trade tensions between

Southeast Asia: A Region

of Nuanced Opportunity

The combined population of Southeast Asia is greater than that of the US.

This exciting region, with a fast-growing apparel market, young consumer

base and rapidly expanding e-commerce, presents a real opportunity for

fashion players. While consumers in the region have enough in common

to suggest that brands can develop a regional strategy that will produce

results, there are also notable dierences between countries, implying a

tailored approach is required for success at scale.

by Aimee Kim, Ali Potia and Simon Wintels

In-Depth

26

Some 40 percent of the population

is under the age of 25, compared

with 28 percent in China and 30

percent in the US.

27

China and the US. On the other hand, regulatory

diculties do exist, with the Philippines, Thailand

and Indonesia requiring by law for foreign entrants

to enter through local partners unless they put

down substantial capital investments. Meanwhile

counterfeit fashion is prevalent, particularly in

Indonesia where copyright laws, or lack thereof,

remain a sizeable concern.

When it comes to e-commerce, some

countries are ahead of others. Singapore is a more

mature and slower growing e-commerce market,

yet brick-and-mortar remain important for

apparel retail and account for 91 percent of sales.

40

Digital payments are popular in Singapore and

Malaysia, but less so in Indonesia and Vietnam,

where a culture of cash-on-delivery continues

to dominate.

Tastes in fashion vary between countries;

Filipinos have a high anity with western

brands, are seeing a significant shift away from

the “tiangge” culture of flea markets and bazaars

towards international fast fashion brands, and

are also partaking in the explosion of athleisure,

while Thai consumers demonstrate curiosity for

brands from both Europe and other Asian nations

like Japan and Korea. Both Indonesia and Malaysia

meanwhile, are predominantly Muslim countries

and have their own distinct narratives in terms of

modest fashion trends.

For international brands entering

Southeast Asia, the challenge is both simple and

complex. On one hand, for players that are trying

to establish a toehold in the market, there is clearly

great potential to roll out across the region, as

free trade operates within the bloc and certain

demographics share similar tastes across the

countries in the region. On the other, for success at

scale, fashion players need to retain the flexibility

to cater to local needs. That may mean being

prepared to take tough decisions on where they

are most likely to find traction and establishing a

tailored strategy for each country.

The authors of this article work within McKinsey and Company’s Apparel,

Fashion and Luxury group, serving a range of clients across Southeast Asia.

02. Beyond China

For success at scale, fashion

players need to retain the lexibility

to cater to local needs. That may

mean being prepared to take

tough decisions on where they

are most likely to ind traction and

establishing a tailored strategy for

each country.

27

A model showcases designs on the runway during Jakarta Fashion Week.

Ulet Ifansasti/Getty Images

28

The State of Fashion 2020

28

In-Depth

Russia: Signs of Resurgence

in a Polarised Market

Slower economic growth provides a challenging backdrop for the Russian

fashion sector, but players have seen success supporting price-conscious

consumers, as well as high-spending tourists lured in by attractive prices

and visitor-friendly policies. Since online channels are ultimately winning

market share and new platforms continue to emerge in this highly

dynamic space, a strong digital presence can be a route to success.

by Alex Sukharevsky, Denis Emelyantsev, Karl-Hendrik Magnus and Patrick Guggenberger

Although Russia — the world’s ninth largest

apparel market — has started to show some signs

of recovery, the economic slowdown that began

in 2014 has significantly dampened spending and

consumer confidence, which remains firmly in

negative territory.

41

Last year’s VAT increases

coupled with five consecutive years of stagnating

real incomes have added to the burden. But even in

this challenging environment, there are opportu-

nities for fashion players in certain categories.

Players who can compete on price represent

one opportunity to appeal to consumers that

continue to move down the price ladder, while

those catering to the luxury market — especially

foreign tourists — are another. The third lies

in e-commerce, a sector that continues to grow

rapidly and is seeing a great deal of change.

In 2019, Russia’s budget-conscious fashion

consumers are increasingly looking for value

for money: 57 percent often shop around to get

the best deals on their preferred labels. Less

expensive retailers that can simultaneously deliver

“fashionable” clothing are benefiting; internation-

al players such as H&M and Zara have long had a

presence in Russia and continue to open stores.

Domestic retailers such as Gloria Jeans, Detskyi

Mir, Tvoe and Melon Fashion Group are also

seizing the opportunity. Sales at Tvoe, for example,

have shot up by 161 percent since the beginning

of 2019, while Melon Fashion Group has outlined

24 percent growth plans, driven by new store

openings, relocations and the expansion of existing

sites along with an increase in online sales.

At the other end of the spectrum, several

luxury brands saw their highest revenue in at least

four years in 2018, including Chanel, Dior, Tiany

& Co and Bulgari.

42

Russia’s luxury consumers

have been spending more at home, while the depre-

ciating rouble has made Russia more attractive for

fashion-seeking tourists, particularly from China.

Chinese tourists were up almost 25 percent in the

first half of 2019 from the previous year and collec-

tively, are expected to spend more than $1.1 billion

in total this year.

43

The Russian government has

also introduced a series of targeted policies, from

VAT refunds to relaxed visa requirements.

The depreciating rouble has

made Russia more attractive

for fashion-seeking tourists,

particularly from China.

2929

02. Beyond China

Luxury retailers have moved to ensure

their prices are competitive with those in Europe;

in 2015, Tsum became the first retailer in Russia

to actively move towards matching prices in Milan

and Paris. It also oered Chinese-speaking sales

sta and Chinese language in-store signage and

in 2018, became the first major Russian retailer

to accept WeChat Pay, making transactions even

easier for Chinese customers.

The third opportunity in Russia stems from

the strong growth and dynamism of e-commerce.

Internet penetration in Russia is high and Russians

spend an average of 6.5 hours a day on the internet.

In 2018, online sales accounted for more than 10

percent of all apparel sales in the market, which

represents double the 5 percent share seen just

five years prior.

44

Online marketplaces capture

the lion’s share of online apparel sales and are

expected to continue growing.

Multi-national companies like Alibaba’s

AliExpress and Global Fashion Group’s Lamoda

have done well, together with local players like

Wildberries; in August, Wildberries.ru became

Russia’s largest clothing retailer, having grown

revenue 79 percent year-on-year for the first six

months of 2019. Other platforms by major groups

like Sberbank-Yandex and USM have started

to emerge, including the recently announced

AliExpress Russia joint-venture — a tie-up

between Russian internet giant Mail.ru, Russian

telecom Megafon and China’s Alibaba, with

support from Russia’s sovereign wealth fund.

These areas of growth suggest that oppor-

tunities do exist in the region, both for luxury

brands and for players who are price competitive.

Delivering great value apparel with a high degree

of fashionability will be an increasingly winning

formula for many. Promotions are dominant;

international players should explore pricing

levers, either at a mass-level or by taking a more

personalised approach through customer value

maximisation (CVM). Luxury incumbents

should further focus on building loyalty with core

consumers as well as millennials to drive growth,

in part through understanding the increasing

importance of online as an information channel

for consumers and, as such, developing their digital

oering through online stores or partnering with

online multi-brands.

Players who wish to enter Russia should

think about their options. Foreign brands

may want to start with a digital presence that

introduces them to consumers before launching

a physical presence, focusing on Moscow and

St. Petersburg, which hold the lion’s share of value

in a logistically-challenging country that spans

11 time zones. Some players might instead choose

to partner with a fast-growing local player, either

a multi-brand brick-and-mortar retailer, or an

online-only company. Brands may do well to build

a local presence as part of a much larger strategy

to serve the new generation of digitally connected

and “global” Russian fashion consumers, with

fewer language and information barriers than

ever before.

The authors of this article work within McKinsey and Company’s Apparel,

Fashion and Luxury group, serving a range of clients across Russia.

In 2018, online sales accounted

for more than 10 percent of all

apparel sales in the market, which

represents double the 5 percent

share seen just ive years prior.

30

The State of Fashion 2020

Annual fashion sales in the Middle East’s

Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) markets amount

to $50 billion, reflecting the region’s significant

financial clout. Spending in some GCC countries

is among the highest on a per capita basis globally,

reaching approximately $500 and $1,600 per person

in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates

(UAE) respectively.

45

Dubai is the region’s shopping

capital, but other markets are maturing fast, with

Saudi Arabia taking a place at the top table.

However, economic cycles in the GCC

countries are closely tied to global commodity

prices which brings challenges to the current

climate. Oil prices are around 35 percent lower

than they were in 2010-2014 — and economic

growth is slowing. Meanwhile, lower rents are

being oset by rising labour costs, including new

visa and administrative fees, and reduced energy

subsidies. Geopolitical events in the region pose a

challenge too. The last few years saw a notable rise

in business closures especially in the wholesale

and retail sectors.

Despite its complications, the GCC presents

significant opportunities for fashion players, many

of which have operated successfully there for

years. Dubai will continue to play an important

role as the region’s window to the fashion world,

supported by world-class malls oering a top-end

customer experience. Tourism will continue to

be an important revenue driver; the city’s Expo

2020 is billed as the “World’s Greatest Show,”

a glittering coming together of technology, art,

food and creativity that is expected to attract at

least 25 million visitors.

Elsewhere, the fashion market in Saudi

Arabia is going through some dynamic shifts.

The kingdom is the biggest and most populous

country in the region and is investing heavily in

building a thriving cultural scene to attract locals

and visitors alike. Mega-infrastructure products

include Diriyah Gate, a 7.1-million-square-

metre development, and The Red Sea Project,

In-Depth

The GCC: A Region in Transition

When it comes to shopping, Middle Eastern consumers are experienced

and increasingly savvy. Retail is a favourite cultural pastime, and

informed consumers can’t get enough of luxury items, in-store

experiences and the latest fashions. That said, the Gulf Cooperation

Council markets are changing, amid shifting economic currents and the

rise of digital. For brands this implies risks, but also opportunities.

by Nitasha Walia, Ahmed Youssef, Abdellah Iftahy and Martins Mellens

Spending in some countries

is among the highest on a per

capita basis globally, reaching

approximately $500 and $1,600

per person in Saudi Arabia and the

United Arab Emirates respectively.

31

comprising of 14 luxury and hyper-luxury hotels.

Attractions such as the Diriyah E-Prix will see

Formula E racing (electric cars) on the streets of

Riyadh. Winter at Tantora is a new music and arts

festival founded in 2018, combining concerts and

exhibitions with desert vistas, balloon flights and

horse races. Women are now playing an increas-

ingly active and important role in the workforce.

Indeed, the recent relaxation of rules on women’s

dress have the potential to disrupt how women,

both local and foreigners, consume fashion in

Saudi Arabia. These developments should also

encourage more local spending. Currently over

50 percent of Saudi spend on leisure and entertain-

ment is outside the kingdom, with categories like

luxury nearing 70 percent.

Middle Eastern consumers as a whole are

also becoming increasingly connected. Internet

penetration in the UAE and Saudi Arabia is at 99

and 89 percent respectively, compared to just 57

percent in China.

46

E-commerce, therefore, is fast

becoming a table stake in the region. It is set to

grow at around 40 percent a year over the next five

years, increasing its penetration to 9 percent from

the current 2; in some fashion categories in Saudi,

it is already at 20 percent. Internet platforms

are thriving, and international digital players

including Yoox Net-a-Porter, Farfetch, Jollychic

and Amazon are wooing the local consumer. Local

players too, both omnichannel and pure players

like Ounass, The Modist and Namshi have sprung

up to capitalise on this trend.

Consumer attitudes too are changing,

as they want more value, transparency and local

content from fashion players. Middle Eastern

fashion companies are raising their game, with

designers, platforms, social media stars and local

style trends starting to feature more in the global

fashion narrative. The Middle East is starting to

shift from being a historical importer of fashion

trends to a nascent exporter. Following the

success of Lebanese designers like Elie Saab and

Rabih Kayrouz on the international stage, new

designers from GCC countries are making their

mark; Kuwait’s Yousef Aljasmi and Bahrain’s Hala

Kaiksow are names with growing international

recognition and others are riding on their tailcoats.

Fashion players must think carefully

about how best to play in the GCC. Partnerships

will continue to play an important role in the

form of franchise relationships, joint ventures or,

in some cases, distribution-only models. Local

family-owned businesses including Alhokair,

Alshaya, Al Tayer, Azadea, Chalhoub, Saudi

Jawahir Trading and Rubaiyat, among others, are

the lynchpins of the local scene, and will play an

important role in physical, and increasingly digital,

retail. A winning e-commerce strategy, intimate

knowledge of the consumer and cost excellence

will be crucial.

No doubt, the GCC will continue to be

an important fashion market, but brands that

maximise performance across multiple channels

and territories are most likely to outperform.

The authors of this article work within McKinsey and Company’s Apparel,

Fashion and Luxury group, serving a range of clients across the Middle East.

02. Beyond China

A model walks the runway at the Yousef Al-Jasmi show during Dubai Fashion Forward

Stuart C. Wilson/Getty Images for Fashion Forward

32

The State of Fashion 2020

CONSUMER

SHIFTS

33

03. NEXT GEN SOCIAL

As traditional engagement models struggle on

established social media platforms, fashion players will

need to rethink their strategy and ind ways to maximise

their return on marketing spend. Attention-grabbing

content will be key, deployed on the right platform for

each market, using persuasive calls-to-action and,

wherever possible, a seamless link to checkout.

The collective reach of the social media

giants is staggering. Facebook reported 2.5 billion

monthly active users in September 2019, and

both Instagram and WeChat have more than a

billion users each. Yet, growth seems to be slowing

and users are spending less time on some of the

major platforms: in the US, average daily time on

Facebook fell to 37 minutes a day from 41 minutes

in 2017.

47

Stagnating enthusiasm has not stopped

advertising rates and revenues rising at the big

platforms. According to one report, the average

digital ad cost has risen 12 percent in two years,

but digital ad expenditure rose 42 percent,

48

helping

analysts forecast Facebook’s revenue in 2019

above $69 billion at the time of writing,

49

up

70 percent from 2017 and equal to all print media

ad spending.

50

However, visits to those advertisers

on social media have risen only 11 percent.

51

The challenge is that advertising overload

might be hurting engagement. Global consum-

er-goods giant P&G discovered that people spent

less than two seconds on average looking at its ads

on mobile feeds — and that those ads appeared too

often. Chief brand ocer Marc Pritchard explained

in the Wall Street Journal, “We’re trying to reduce

the amount of times we reach the same person over

and over again.”

52

The data suggests that it is time for brands

to rethink their social media strategy. Specifically,

they need to re-evaluate how to exploit existing

platforms more eectively, capitalise on the rise

of new platforms and understand how to generate

direct sales through social platforms.

The typical route to reach a large audience

on existing platforms such as Instagram is to either

build followers organically or borrow followers

using influencers — both these routes are starting

to wobble. UK cosmetics company Lush realised

that its organic newsfeed content reached only

6 percent of its online followers and became tired of

fighting the platforms’ own advertising algorithms.

It decided to shut down its social media accounts to

regain ownership of its communication by relying

on brand-owned channels instead. While this may

be an extreme step to take, it demonstrates the

lengths that some brands are willing to go to try to

overcome current challenges on social media.

While an incredible 86 percent of

companies use influencer marketing,

53

the

engagement rate for such sponsored posts on

Instagram dropped from 4 percent in Q1 2016 to

2.4 percent in Q1 2019.

54

Facebook’s and Twitter’s

numbers are even worse at 0.37 percent and 0.05

percent respectively.

55

The harsh reality is that it

is increasingly hard to excite and inspire audiences

34

The State of Fashion 2020

Consumer Shifts

who are overwhelmed and overstimulated. Going

forward, a static image displaying a product with a

model or influencer will no longer cut it. Industry

executives believe that the top trend shaping

the fashion industry within the next 12 months

will be a rise in the importance of “storytelling”

and marketing strategies that resemble media

productions.

56

Arnold Ma, chief executive of creative

digital agency Qumin, suggests players should

move up the influencer funnel, partnering with

individuals or other brands who truly live the

lifestyle and can tell an authentic story, rather than

blindly paying popular more generic influencers to

promote their products.

Ralph Lauren adopted this approach when

it worked with fashion publication Highsnobiety

for its 50

th

anniversary. The published advertorial

followed the impact the brand had on designers,

collectors and the fashion industry from the Ivy

League to the streets of Brooklyn.

57

Another tactic to grab consumers’ attention

is to use social media to tap into the drop culture

typically associated with streetwear labels.

Consumers’ desire to be in the know and to have

an exclusive product drives a large part of the

purchase. Last year, for example, Burberry released

a limited-edition Ricardo Tisci T-shirt available

only on Instagram and WeChat for 24 hours.

The company used the hype around this drop to

release more limited-edition designs available on

social media or exclusively in its London flagship

store for just 24 hours.

As data shows, it is getting harder to stand

out in established social media. Fashion players

need to understand how to gain traction on newer

platforms. 70 percent of fashion executives believe

that increased exploration of and spend