Journal of Interdisciplinary Undergraduate Research Journal of Interdisciplinary Undergraduate Research

Volume 12 Article 1

2020

A Complete Chronology of the Israelites in Egypt: A Textual Study A Complete Chronology of the Israelites in Egypt: A Textual Study

of the Length of the Sojourn from a Seventh-day Adventist of the Length of the Sojourn from a Seventh-day Adventist

Perspective Perspective

Matthew Bronson

Follow this and additional works at: https://knowledge.e.southern.edu/jiur

Part of the Education Commons, and the Religion Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Bronson, Matthew (2020) "A Complete Chronology of the Israelites in Egypt: A Textual Study of the Length

of the Sojourn from a Seventh-day Adventist Perspective,"

Journal of Interdisciplinary Undergraduate

Research

: Vol. 12 , Article 1.

Available at: https://knowledge.e.southern.edu/jiur/vol12/iss1/1

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Peer Reviewed Journals at Knowledge Exchange. It

has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Interdisciplinary Undergraduate Research by an authorized editor of

Knowledge Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected].

A Complete Chronology of the Israelites in Egypt: A Textual Study of the Length of the

Sojourn from a Seventh-day Adventist Perspective

Matthew Bronson

RELB 495 Biblical Studies Directed Study

Michael Hasel

April 11, 2019

ii

Abstract

Regarding the chronology of the Israelite Exodus from Egypt, two major theories are

readily apparent: either the Israelites sojourned in the land of Egypt for a total of 430

years, or else for 215 years in Egypt after sojourning in the land of Canaan for 215 years.

This question is examined from a Seventh-day Adventist perspective, with precedence

given to Scriptural passages. An overall chronological framework is constructed for

context, dealing with selected issues in the study of biblical chronology. The primary

arguments for each theory are individually assessed, as are objections to many of the

arguments. A small treatise on historical Seventh-day Adventist views on the subject is

included, followed by a study of the earliest biblical manuscripts containing a significant

variant reading. This research is concluded with a critique of a more recent Adventist

work, along with a more anecdotal study on modern genealogies. Ultimately, each of the

theories may be shown to be equally valid as far as possibility is concerned, and ought to

be considered viable options to explain a major lacuna in a literal interpretation of

biblical chronology.

1

Introduction

The account of the Exodus of the Israelites from Egypt is perhaps one of the most

well-known stories in the world today. What is considerably less well known is the

precise amount of time that was spent by the Israelites in the land of Egypt. For more

than two thousand years there have been combatting theories based off a few verses in

Scripture presenting a case for either a “long” or a “short” sojourn in Egypt,

approximately 430 and 215 years long, respectively. The question naturally follows

whether or not Seventh-day Adventists ought to consider the 430 or the 215 years to be

the accurate amount of time the Israelites were in Egypt. Although a definitive answer

may remain elusive, a surprisingly strong case may be made for each of these

conclusions; additionally, the history of each perspective and the issues involved in the

discussion are worthy of study. Notwithstanding the numerous difficulties, the collective

chronologies given in both the Old and New Testaments are marked by extraordinary

internal consistency. For the purposes of this research, biblical sources are most seriously

considered for the determination of dates in the chronology, and a high view of Scripture

and inspiration is maintained.

Date of the Exodus

In order to establish the dates surrounding the sojourn in Egypt, the date of the

Exodus must first be accurately assigned; this will furthermore offer a helpful frame of

reference in the following discussion. The determination of the dates for the events of the

Israelite sojourn in Egypt must necessarily involve working backwards through history;

from a biblical perspective, the year of the end of the sojourn (i.e. the Exodus) is dated to

ca. 1445 BC. Any who take the Bible literally will experience difficulty determining the

2

Exodus to have taken place any time other than the fifteenth century BC. 1 Kings 6:1

relates, “And it came to pass in the four hundred and eightieth year after the children of

Israel had come out of the land of Egypt, in the fourth year of Solomon’s reign over

Israel, in the month of Ziv, which is the second month, that he began to build the house of

the LORD” (NKJV). Solomon, who reigned a total of 40 years (I Kings 11:42; II Chron.

11:30), died ca. 930 BC.

1

This would place the fourth year of his reign ca. 966 BC, which

in turn would place the date of the Exodus 480 years prior—ca. 1445 B.C., mid-fifteenth

century BC. Furthermore, this year is corroborated by Jephthah’s statement in Judges

11:26 that Israel conquered territory in the Transjordan approximately 300 years prior.

2

In spite of the biblical date given for the Exodus of the Israelites out of Egypt, a

thirteenth-century Exodus, during the reign of Ramesses II, remains the popular view.

3

This is largely due to the fact that Exodus 1:11 states that the Israelites “built for Pharaoh

supply cities, Pithom and Ramses” (NKJV); from this it is suggested that a city bearing

his name would not have existed before Ramesses ruled. While it is true that an

anachronism ostensibly exists in this passage, it is unwarranted to disregard every other

passage in favor of this—it is entirely likely that the name for the city of Ramesses might

have been updated at a later point in history to reflect the current name at that time, which

1

Edwin R. Thiele, “The Chronology of the Kings of Judah and Israel” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 3,

no. 3 (1944).

2

With the Exodus taking place ca. 1445 B.C., the conquering of Heshbon would have happened

approximately 40 years later, ca. 1405 B.C. (Num. 21:21–31; Deut. 1:3–5; 2:26–37). 300 years after this

date is ca. 1105 B.C., a date that allows for 40-year reigns for David and Saul, as well as the judgeship of

Samuel (see I Samuel 7:15; 13:1; I Kings 2:10; II Chronicles 29:27; Acts 13:21).

3

William F. Albright, “Archaeology and the Date of the Hebrew Conquest of Palestine,” BASOR 58

(1935): 10–18; idem, “Further Light on the History of Israel from Lachish and Megiddo,” BASOR 68

(1937): 22–26; idem, “The Israelite Conquest of Canaan in the Light of Archaeology,” BASOR 74 (1939):

11–23. Kenneth A. Kitchen, Pharaoh Triumphant: The Life and Times of Ramesses II, King of Egypt

(Warminster, England: Aris & Phillips, 1982); James K. Hoffmeier, Israel in Egypt (New York: Oxford

University Press, 1996); Joyce A. Tyldesley, Ramesses: Egypt’s Greatest Pharaoh (New York: Penguin,

2001); etc.

3

was not an uncommon practice.

4

Another biblical objection to the fifteenth century BC

date for the Exodus has been raised on the basis of the chronology of Israelite judges,

which is dealt with at length in the excursus following this study.

Issues in Calculating the Length of the Sojourn

The length of the Israelite sojourn is mainly contended on the basis of a few

passages in the Bible. Exodus 12:40 relates, “Now the sojourn of the children of Israel

who lived in Egypt was four hundred and thirty years” (NKJV). Naturally, a plain reading

of the Hebrew text indicates that the “dwelling of the sons of Israel who lived in Egypt”

was 430 years in total, which would mean Jacob and his family entered Egypt around the

year 1875 BC. The Septuagint (LXX) records a variation in this verse, stating that the

“sojourn of the children of Israel who lived in the land of Egypt and the land of Canaan

was 430 years” (emphasis added). The question may be very reasonably posed whether or

not this represents a needless expansion to the text, or if it actually points to an early

tradition associated with this verse. The apostle Paul, in the first century AD, seems to

have been either familiar with such a tradition or else simply relying entirely on the

Septuagint reading when he wrote his epistle to the Galatians: “And this I say, that the

law, which was four hundred and thirty years later, cannot annul the covenant that was

confirmed before by God in Christ, that it should make the promise of no effect” (Gal.

3:17, NKJV). This statement was made in the context of God’s promise to Abraham to

inherit the land of Canaan, which, in Paul’s mind, seemed to have been covenanted to

Abraham 430 years before the events surrounding the Exodus. All chronology in the

4

William Shea, “Exodus, Date of,” International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, vol. 2, ed. Bromiley

(Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1985), 232; Bryant Wood, “The Rise and Fall of the 13

th

Century

Exodus/Conquest Theory,” Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 48 (2005): 479.

4

Bible may be reckoned with details outlined in the text itself with relative ease, excepting

this single issue: whether or not 1875 BC indicates an entrance into the land of Egypt by

Jacob or into the land of Canaan by Abraham.

If the Septuagint preserved the correct reading, then Abraham entered the land of

Canaan in 1875 BC, at the age of 75 (Genesis 12:1–7, conf. Gal. 3:15–18). Twenty-five

years later, Abraham begot his son Isaac (Gen. 21:5), who in turn begot Jacob at the age

of 60 (Gen. 25:26). 130 years later Jacob would have entered Egypt (ca. 1660 BC), and

the first 215 years of the sojourn would have taken place in Canaan, while the remaining

215 years happened in Egypt. If the Septuagint in actuality contains an unoriginal

addition to the text (which seems to have happened rather often)

5

, then all 430 years

would have been spent in the land of Goshen. There are fairly strong cases that may be

made for both a 215-year and a 430-year sojourn in Egypt, and each will be discussed at

length below along with a review of the history of Seventh-day Adventist views on the

topic.

Chronological Context in the Lives of Jacob and Joseph

The book of Genesis in particular gives relatively detailed information concerning

the amount of time that transpired between events outlined therein; the only major lacuna

is the amount of time between the death of Joseph and the birth of Moses (to be discussed

further below). Since Moses was “eighty years old” when he “stood before Pharaoh” (Ex.

7:7, NKJV), and the Exodus took place shortly after, a tentative birth year for Moses is

1525 BC. It is reasonable that other dates may be extrapolated from by alternatively

5

See Gerhard Larsson, “The Chronology of the Pentateuch: A Comparison of the MT and LXX,” Journal

of Biblical Literature 102, no. 3 (1983): 401–09.

5

working forward from the book of Genesis; this will additionally proffer useful context

for the subsequent discussion.

A consecutive chronological chain is maintained throughout the whole of

Scripture with few exceptions—the most glaring with regards to this discussion is that

which exists between the lives of the patriarch Jacob and his descendant Moses. The age

at the birth of their firstborn as well as the age at death is given for every patriarch from

Adam until Isaac; the remaining amount of time that passed from Jacob until his

descendants left Egypt must be reconstructed. Genesis 50:26 indicates that Joseph lived a

total of 110 years. Jacob was 130 years old when he entered into Egypt to begin his

sojourn in Egypt.

6

Jacob then lived another 17 years in Egypt, and died at the age of 147

(Gen. 47:28); if Jacob’s age at Joseph’s birth could be ascertained, then a chronology of

their lives could be determined with relative accuracy. Genesis 41:46 states that “Joseph

was thirty years old when he stood before Pharaoh king of Egypt…”—he was reunited

with his father Jacob after 7 years of plenty and an additional 2 years of famine (Gen.

45:6, 11–13). This makes Jacob approximately 91 years older than his son Joseph (in

other words, Jacob would have been about 91 years of age at the time of Joseph’s birth).

This would mean the time between the death of Jacob and Joseph was 54 years.

7

Therefore, Jacob must have been 77 years old when he met Rachel, 84 years old when he

6

It is worth noting that Jacob’s response to Pharaoh was worded in such a way as to communicate that he

considered himself to have already been “sojourning” (דוגמ) prior to his time in Egypt: “The days of the

years of my sojourning are 130 years…” (Gen. 47:9, ESV). Canaan is at least five times referred to as a

land of “sojourning” for the descendants of Abraham (Gen. 17:8; 28:4; 36:7; 37:1; Ex. 6:4). This term is

not, however, used in Exodus 12:40.

7

Interestingly, Ellen White was familiar with this specific point. In Patriarchs and Prophets, she writes,

“Joseph outlived his father fifty-four years” (PP 240.1). She must have either been especially shown this,

calculated this through her own study, heard it presented at some point in her lifetime, or found it published

in literature at the time.

6

married both her and Leah, and between 84 and 91 years old when he begot his children,

excepting Benjamin (Gen. 31:41, conf. Gen. 29, 30).

Overview of Primary Arguments

Arguments in favor of a 215-year sojourn in the land of Egypt generally seem to

circulate around Paul’s statement in Galatians as well as the genealogy of Moses

recorded in Exodus 6:14–20 and Numbers 26:57–59.

8

The reasoning follows that if Levi

lived 137 years (Ex. 6:16), and was born when his father was about 87 years of age (ca.

1919 BC, or alternatively ca. 1704 BC; see Gen. 29:30–34), then the entire lifespans of

Levi’s son Kohath (133 years, Ex. 6:18) and his grandson Amram (137 years, Ex. 6:20)

would be engulfed in the sheer length of a 430-year sojourn in Egypt. In other terms, if

the sojourn in Egypt lasted 430 years, then Moses’s father Amram would have died

before Moses was ever born—assuming that the genealogies correctly depict Moses as

the great-grandson of Levi. Furthermore, God had told Abraham that “in the fourth

generation” his descendants would return again to Canaan from the land of their slavery,

“for the iniquity of the Amorites is not yet complete” (Gen. 15:16, NKJV). Moses, of the

8

Martin Anstey, The Romance of Bible Chronology, (London: Marshall, 1913), 116–18; Philip Mauro, The

Chronology of the Bible (New York: George H. Doran, 1922), 37–40; David L. Cooper, Messiah: His First

Coming Scheduled (Elsternwick, Victoria: Bible Research Society, 1945), 129–34; Edwin R. Thiele,

“Chronology, Old Testament,” The Zondervan Pictorial Bible Dictionary, ed. Merrill C. Tenney (Grand

Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1967), 166–67; The Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary (Washington:

Review and Herald, 1953), 174–96.

7

fourth generation from those who first entered Egypt, is considered to be the fulfillment

of this promise. In order to explain the Masoretic Text (MT) reading in Exodus 12:40, an

explanation has been proffered that Canaan was part of Egypt’s territory in the fifteenth

century BC, and that the divergent readings are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

9

The

400 years of affliction in Genesis 15:13 is thought to apply to all the descendants of

Abraham, starting with Isaac, occurring in both Canaan and Egypt.

Proponents of the 430-year sojourn seem to base their claims primarily on the

weaknesses of the opposing theory, as well as a plain reading of Exodus 12:40 and

Genesis 15:13 and 14, with few variations.

10

“Then He said to Abram: ‘Know certainly

that your descendants will be strangers in a land that is not theirs, and will serve them,

and they will afflict them four hundred years. And also the nation whom they serve I will

judge; afterward they shall come out with great possessions’” (Gen. 15:13, 14, NKJV).

Those who maintain that only 215 years were spent in Egypt point out that, technically,

only affliction is predicted for 400 years, not necessarily slavery. However, it is rather

difficult to construe 400 years of “affliction” partially taking place to any degree of

equality in Canaan as that which was experienced in Egypt. Furthermore, if Jacob were to

have entered Egypt in 1660 BC rather than 1875 BC, than his death 17 years later, as well

as the death of his son Joseph 54 years after that, would place the enslaving of the

9

Francis D. Nichol, SDA Bible Commentary, 315–17. It bears mentioning, however, that there is no

instance in Scripture where “the land of Canaan” is otherwise referred to as “the land of Egypt.”

10

Eric T. Peet, and J. W. Jack, “The Date of the Exodus,” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 12, no. 3/4

(1926): 322; Merrill F. Unger, Archaeology and the Old Testament (London: Pickering & Inglis, 1964),

106, 150; Gleason Leonard Archer, A Survey of Old Testament Introduction, Rev. ed. (Chicago: Moddy

Press, 1974), 205, 211–12; Kenneth A. Kitchen, Ancient Orient and Old Testament (Chicago: Inter-Varsity

Press, 1966), 53–56; Harold Hoehner, “The Duration of the Egyptian Bondage,” Bibliotheca Sacra 126, no.

504 (1969): 306–16; Paul J. Ray Jr., “The Duration of the Israelite Sojourn in Egypt,” Andrews University

Seminary Studies 24, no. 3 (1986): 231–48; Andrew E. Steinmann, From Abraham to Paul: A Biblical

Chronology (St. Louis: MO: Concordia, 2011), 68–70.

8

Israelites after ca. 1590 BC, only 64 years before the birth of Moses. It has been pointed

out that it would have been miraculously difficult for the descendants of Jacob to

multiply to the 601,730 males recorded in the book of Numbers in such a short period of

time.

11

In order to explain the four generations of Genesis 15, it is proposed that there are

gaps in the genealogies, and that the term “generation” is a non-specific period of time

based on the number of years people lived in a given time or place (e.g. the number of

years Abraham lived, a generation being equal to “100 years”).

12

Historical Review of Seventh-day Adventist Views

The history of Seventh-day Adventist views on the subject demonstrates a lack of

agreement over the years concerning the two aforementioned views; the 430 years seem

more recently to be preferred as the more likely case. Traditionally, Seventh-day

Adventists defended Paul’s statement in Galatians by supporting a 215-year sojourn in

Egypt in the church’s official Bible commentary. The same lines of reasoning are echoed

in an appendix entry in Ellen White’s Patriarchs and Prophets, published in 1890.

Of greater interest are the statements made by Ellen White herself. First published

in 1864, she wrote in the third volume of Spiritual Gifts (later republished in The Spirit of

Prophecy, vol. 1 and The Signs of the Times) concerning the predicted spoiling of the

Egyptians: “The Lord revealed this to Abraham about four hundred years before it was

fulfilled” (3SG 229.1; 1SP 205.1, ST April 1, 1880 Par. 3). She went on years later to

make several more clear statements written in historical narrative siding with Paul’s view

that approximately 400 years had transpired between Abraham and the Exodus: “In the

11

Hoehner, “Duration of Egyptian Bondage,” 311.

12

K. F. Keil and F. Delitzsch, The Pentateuch, vol. 1, trans. James Martin, in Biblical Commentary on the

Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: 1952), 216.

9

days of Abraham [God] declared that the idolatrous Amorites should still be spared until

the fourth generation … For more than four hundred years he spared them…” (LP 318.1,

emphasis added). Seventh-day Adventists seem to have felt doubly pressured, as it were,

to defend both Paul’s statement and Ellen White’s statements concerning the length of

the sojourn in Egypt—specifically in the book Patriarchs and Prophets, published 1890.

She wrote, “Four hundred years before, God had shown to Abraham the future

oppression of His people, under the figure of a smoking furnace and a burning lamp” (PP

267.2); “Although the Amorites were idolaters, whose life was justly forfeited by their

great wickedness, God spared them four hundred years to give them unmistakable

evidence that He was the only true God, the Maker of heaven and earth” (PP 434.2,

emphasis added).

13

Lastly, she once more very clearly stated that the “covenant made

with Abraham” took place “four hundred and thirty years before the law was spoken on

Sinai…” (ST August 24, 1891, par. 10). Ellen White furthermore seemed to have

believed that, prior to Moses’s time, it was only the “two last kings who had occupied the

throne of Egypt” that “had been tyrannical, and had cruelly entreated the Hebrews,”

which would be irreconcilable with a 400-year enslavement (3SG 240.2).

In spite of these statements, in three other published works Ellen White seemingly

contradicts herself, siding instead with what must be considered the theory of the 430-

year sojourn. She wrote, “For four hundred years they had been in Egypt, and had been in

slavery to the Egyptians” (RH January 9, 1894, par. 6); “The Lord had fulfilled the word

that He spoke to Abraham when He declared that after the children of Israel had been in

13

Technically, her statement on page 281 is ambiguous, as it is merely a quotation from Genesis 15:13, 14

(which mentions both “sojourning” and “slavery,” with the 400 years being perceived as referring

exclusively to “affliction”). Given the context of Mrs. White’s other statements, she most likely must have

intended this to be understood in the light of a 215-year sojourn in Egypt.

10

bondage four hundred years, He would deliver them” (GCB March 30, 1903, par. 15,

emphasis added).

14

In the eighth volume of Testimonies for the Church, she wrote, “After

they had been in slavery for nearly four hundred years, God delivered them by a

wonderful manifestation of His power” (8T 207.1). It is interesting to note that each of

Ellen White’s statements that pertain to a 215-year sojourn in Egypt were made between

the years 1864 and 1891, while each of her statements that seemingly support 430 years

fall without exception between 1894 and 1904. There are three apparent possibilities:

either Ellen White confused the two concepts in her mind while she wrote, came to a

different understanding sometime between 1891 and 1894, or her incidental statements

siding with a 430-year sojourn are here being misunderstood.

15

One quotation, mentioned in The Great Controversy, may easily escape attention:

William Miller described how the subject of chronology in the Scriptures captured his

interest, and is quoted as listing various time-based predictions in biblical order. Just

before the events of the life of Joseph, he cited “the four hundred years of the sojourn of

Abraham’s seed (Genesis 15:13, NKJV).

16

Although arguably an ambiguous statement,

the order in which the event is mentioned among other biblical time periods seems more

14

Her statement in The Desire of Ages is, once again, technically ambiguous whether or not it refers to a

430-year sojourn in Egypt or 215 years in Canaan and then Egypt.

15

According to the White Estate, the third option is preferable. In Document File 289-D (November 1956),

the White Estate stands by statements made in “historical narrative” as opposed to those made as an

“incidental reference.” It is pointed out that, technically, the 1894 Review and Herald statement describes

both a “sojourn in Egypt for 400 years” as well as “slavery to the Egyptians,” but not necessarily a 400-

year slavery to the Egyptians. Regarding Testimonies for the Church vol. 8, Mrs. White’s original

handwritten draft records, “After they had been in sojourn for nearly 400 years…” rather than “in slavery

for nearly 400 years” (emphasis added). The White Estate believes this change to possibly be a clerical

error that might have escaped Ellen White’s notice, though it was certainly her habit to carefully review

each manuscript before publication. It should be noted that her statement in the General Conference

Bulletin (March 30, 1903, par. 15) was not mentioned in this Document File.

16

Sylvester Bliss, Memoirs of William Miller (Boston, MA: Joshua V. Himes, 1853), 74–75.

11

indicative of a belief in a 215-year sojourn in Egypt, which would explain how early

Adventists maintained this viewpoint on the subject.

As mentioned previously, the Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary published

in 1953 defended the traditional view that only the latter 215 years of the Israelite sojourn

were carried out in the land of the Nile. Reflecting what seems to have been the common

Seventh-day Adventist view at the time, each verse involved in this discussion was

interpreted to be in line with these 215 years. It is very probable that Dr. Edwin Thiele,

being one of the scholars that contributed to the Bible commentary, had much to do with

the section entitled “The Chronology of Early Bible History.”

17

Although the 215-year

theory is upheld in this publication, Thiele elsewhere expressed greater doubt whether

there exists sufficient evidence from the Old Testament alone to ascertain exactly

whether or not 430 years were spent only in Egypt or in Canaan as well.

18

Today,

Adventist scholars tend to feel that a mere 215 years in Egypt would make the

multiplication of the Israelites reckoned in the Pentateuch an utter impossibility.

19

Chronological Issues

There are several miscellaneous arguments that can be made for either theory

purely on the basis of chronological calculations—one such instance is Acts 13:17–20.

20

The argument is made that because the events of the Exodus, the wanderings in the

wilderness, and the Conquest of Canaan are said to have taken “about four hundred and

fifty years” (v. 20), this must be indicative of a 430-year sojourn.

21

The 430 years of

17

Nichol, SDA Bible Commentary, 174–96. See Hoehner, “Duration of Egyptian Bondage,” 308, footnote.

18

Thiele, “Chronology,” 167.

19

Ray, “Duration of the Israelite Sojourn,” 231–48; Steinmann, “Abraham to Paul,” 69.

20

Ibid., 232.

21

The King James Version and the underlying Textus Receptus have these words positioned to

communicate that the time between the period of the Judges and Samuel the prophet was “about four

hundred and fifty years.” In light of the 480 years between Solomon’s fourth year and the Exodus (1 Kings

12

Exodus 12:40 (or, alternatively, the 400 years of Genesis 15:13), in addition to the 40

years of wilderness wandering (Num. 14:34; Josh. 5:6) makes for 470 (or 440) years. The

length of the Conquest brings the total to approximately 477 (or 447) years.

22

This

accords with the 450 years previously mentioned—however, in all of the available

literature there has been a failure to note that this passage is, in actuality, perfectly

ambiguous with regards to the current discussion, in that it is not specified whether or not

the approximate 450 years began when God “exalted the people when they dwelt as

strangers in the land of Egypt” or when the “God of this people Israel chose our fathers”

(Acts 13:17, NKJV). In other words, it is unclear whether or not the 450 years began with

the entrance to Egypt or with the promise first given in Genesis 12:1–3, when God

“chose” the line of Abraham.

As mentioned above, one of the greater questions in this discourse is the number

of years between the death of Joseph and the birth of Moses. It has been thoroughly

established that Jacob lived in Goshen for 17 more years until his death, and that Joseph

outlived his father 54 years (i.e. a total of 71 years). According to the 430-year sojourn, if

1875 BC marks the entrance of Jacob’s family into Egypt, than Joseph’s death would be

ca. 1804 BC (alternatively, a 215-year sojourn would have Jacob enter Egypt ca. 1660

BC and Joseph die ca. 1589 BC). If Moses were born ca. 1525 BC, than the number of

years between the death of Joseph and the birth of Moses would be either 278 or 63

6:1), it is quickly seen that this is a virtual impossibility. Furthermore, when the chronological details

recorded in the book of Judges are tallied, other issues come to light (see excursus). Manuscript evidence

from the oldest Greek witnesses demonstrates that the original reading has the approximate 450 years

referring to the events listed in verses 17–19 rather than records in Judges, as nearly all modern translations

indicate.

22

In Joshua 14:7, Caleb states that he was “forty years old when Moses the servant of the LORD” sent him

to spy out the land; this event happened two years after the Exodus (Num. 9:1, conf. 10:11–14). Since

Caleb was 85 years old at the end of the “Israelite Conquest” (Josh. 14:10), it would have taken

approximately seven years to conquer the land of Canaan.

13

years, in accordance with the 430-year and 215-year theories, respectively. It seems that

calculations such as these lead many scholars to abandon the 215-year theory in favor of

the far more realistic number. However, there are other issues that deserve consideration:

a major crux of the 430-year theory is that the slavery of the Israelites must last 400 years

(Gen. 15:13).

23

Exodus 1:8 testifies that, after Joseph’s death (v. 6), “there arose a new

king over Egypt who did not know Joseph;” it was this Pharaoh that would have enslaved

the Israelites (vv. 9-11, NKJV). Even if this Pharaoh came to power and subjugated the

Israelites just one year after the death of Joseph, this could only amount to about 358

years of slavery in total—which falls rather short of 400 years.

Textual Information

When all biblical manuscripts and textual data are considered, the Masoretic Text

is overwhelmingly supported as a reliable witness to the original text. As already

mentioned, Exodus 12:40 in the MT reads, “the dwelling of the sons of Israel who dwelt

in Egypt was 430 years” (author’s translation). The Samaritan Pentateuch (SP) contains

the additions “the dwelling of the sons of Israel and their fathers who dwelt in the land of

Canaan and in the land of Egypt was 430 years” (emphasis added); this is also true of

early Septuagint (LXX) manuscripts (those of Codex Vaticanus and Origen’s Hexapla),

23

Hoehner, “Duration of the Egyptian Bondage,” 310; Ray, “Duration of the Israelite Sojourn,” 235.

14

except “Canaan” and “Egypt” are reversed. The fact that the phrase “and their fathers”

appears in differing positions within the verse amongst various ancient witnesses most

likely reveals it to be a later addition attempting to reconcile the apparent discrepancy.

24

In fact, LXX copies of the Pentateuch can be demonstrated often to have attempted to

harmonize difficult passages with a more palatable addition.

25

It is probable that, in light

of the genealogy of Moses, Exodus 12:40 was revised to reconcile what was perceived to

be a glaring inconsistency.

Although demonstrably biased in its translation, the whole of the LXX was most

likely composed between the years 280 BC and AD 125, making it a considerably early

witness to the text of the Old Testament.

26

The SP is also thought to bear an ancient

provenance, and offers readings that are fairly well represented in the manuscripts of the

Dead Sea Scrolls (DSS); although traditionally thought of as a separate text type (and

rightfully so), there is good evidence

that suggests a common origin for many

SP readings that predate the schism

between Samaritans and Jews—

something Vanderkam describes as a

sort of “textual fluidity.”

27

The figure

represents original research

reconstructing manuscript 4Q14 (4QExodus

c

, from Cave IV at Qumran) with space

24

Ray, “Length of the Israelite Sojourn,” 233–34, footnote.

25

Larsson, “Chronology of the Pentateuch,” 405–07.

26

G. Dorival, M. Harl, and O. Munnich, La Bible grecque des Septante: Du judaïsme hellénistique au

christianisme ancient (Paris: Éditions du Cerf, 1988), 111.

27

James C. Vanderkam, “Questions of Canon Viewed through the Dead Sea Scrolls,” Bulletin for Biblical

Research 11, no. 2 (2001): 273–74.

15

consideration, furnishing the reading “and the dwelling of the sons of Israel who dwelt in

the land of Egypt was 430 years” (note the additional portion preceding “Egypt,”

emphasis added).

28

When all textual data is assessed, the MT probably preserves the

correct and original reading—yet on the other hand, the witness of both SP and LXX

manuscripts insisted on a reading for reasons that are perhaps more than coincidental, and

very well may reflect a very early tradition associated with this biblical passage.

Genealogical Issues

One of Ray’s major claims is that genealogical evidence in the Bible clearly

points to missing generations between Levi and Moses.

29

The case is made that since

there are six generations between Judah and Nahshon (1 Chron. 2:3–15; Matt. 1:3–6),

seven generations from Judah to Bezalel (Ex. 35:30; 1 Chron. 2:3–5, 18–20), and

between eight and twelve from Joseph until Joshua (Gen. 41:51, 52; Num. 26:35, 36; 1

Chron. 7:20–27), there are probably one or two missing generations after Amram and

before Moses. Although there are good and thoughtful arguments that the genealogy of

Exodus 6:16–27 is incomplete, there are also several factors that have been failed to be

considered with regards to the opposing theory.

Ray argues that the genealogy of Moses in Exodus 6:16–27 is “stylized,” and goes

so far as to say that there may be confusion and consequent conflating of two different

men named “Amram.”

30

If Seventh-day Adventists believe Moses to have authored the

book of Exodus, it seems hardly likely that Moses would have confused his father with an

28

The circled word in the figure demonstrates a reading in line with the SP, the squared, as seen in

translation, supports the MT. Online scans are courtesy of the Leon Levy Digital Library and the Israel

Antiquities Authority.

29

Ray, “Duration of the Israelite Sojourn,” 236–39, 247–48.

30

Ibid., 237.

16

earlier descendant. It is stated that Jochebed, Moses’s mother, is a “daughter of Levi”

(Ex. 2:1) only in the general sense (i.e. “descendant of Levi”); this is also contrary to a

plain reading, since Jochebed is called both “the daughter of Levi” (Num. 26:59) and

Amram’s “father’s sister” (i.e. both Amram’s aunt and wife, the sister of Kohath, the

daughter of Levi; Ex. 6:20). Although this seems strange by modern standards, it is not

necessary to view these passages through the lens of today’s common practices.

The line of David is said to have been 14 generations beginning with Abraham

(Matt. 1:17; Ruth 4:18–22), and is represented consistently throughout Scripture.

Although a case might be made for missing generations within David’s genealogy, it

nonetheless provides helpful insight into the chronological records found of the Old

Testament.

31

Assuming 11 generations between Judah and David, there are listed at least

14 generations from Levi until Zadok, a contemporary of David (e.g. 1 Kings 2:35), as

demonstrated by the following table:

1 Chron. 2:3–12; Matt. 1:3–6 1 Chron. 6:1–15; Ezra 7:1–5

1 Judah Levi

2 Perez Kohath

3 Hezron Amram

4 Ram Aaron

31

Firstly, the supposed 14 generations between Abraham and David, David and the Exile, and the Exile and

Christ (Matt. 1:17) have gaps: there seem to be 13 listed by Matthew between the Exile and Christ, and

Ahaziah, Joash, and Amaziah are also excluded (Thiele, “Chronology,” 166). If Jacob was 130 while

Joseph was 39 (as established previously), then he would have been about 81 when he bore Joseph in either

1914 or 1699 BC. This would make Judah’s year of birth ca. 1918 or 1703 BC at the earliest, which would

in turn make Judah at least 43 years old at the time Jacob’s family entered Egypt. Since Judah bore Perez

long after his first three sons (see Gen. 38), it is very difficult to believe that Genesis 46:12 is comprised of

a literal record when Perez’s children Hezron and Hamul are counted among the number of descendants

entering Egypt (it is possible that there was perhaps some practice of recording names “in anticipation,”

actually preceding their birth; or perhaps Hezron and Hamul were somehow counted in Er and Onan’s

place, since they died while still in Canaan). Since the fourth year of Solomon’s reign was 966 BC, David

must have been born ca. 1040 BC (2 Sam. 5:4, 5; 1 Kings 2:11). Since Nahshon the son of Amminadab was

leader of the tribe of Judah at the time of the Exodus (Num. 1:7), Salmon, Boaz, Obed, and Jesse would

each need to have been nearly 100 years old when they had their son. While this is possible by the biblical

narrative’s standards (the biblical text seems to suggest that both Boaz and Jesse were rather old by the

time they had children; Ruth 3:10; 1 Sam.17:12), it nevertheless comes across very implausible.

17

5 Amminadab Eliezar

6 Nahshon Phinehas

7 Salmon Abishua

8 Boaz Bukki

9 Obed Uzzi

10 Jesse Zerahiah

11 David

*

Meraioth

12 Solomon

*

(Azariah?) Amariah

13 Rehoboam Ahitub

14 Abijah Zadok

*

*

Known contemporaries of each other (1 Kings 1, 2)

If the genealogy of David is thought to be complete, it begins to be a problematic practice

to add generations to Zadok’s line, since it begins to distance Zadok further from David.

This demonstrates how these generations must not be immediately thought of as

contemporaneous; without ages given at the birth of each child, there is no sure way to

know how long each generation was. Additionally, assuming two extra generations in

Moses’s patriarchal line, a 430-year sojourn would still have Kohath, Amram I, an

unnamed ancestor, and Amram II each waiting over 85 years of their lives before having

their respective sons (a 215-year sojourn has Kohath and Amram waiting an average of at

least 67 years—still rather late, yet not as unreasonable). All this furthermore

demonstrates that to lean too heavily on genealogical data may potentially lead to a

breaking down of one’s own genealogically based argument, as Thiele cautioned.

32

One of the perceived difficulties that inhibit acceptance of a 215-year sojourn in

Egypt is the lineage of Joshua: there are at least eight generations beginning with

Joseph.

33

This at first appears uncontrovertibly irreconcilable with only 63 years between

32

Thiele, “Chronology,” 167.

33

The text of 1 Chronicles 2:20–27 is difficult; there are anywhere from eight to twelve generations

between Joseph and Joshua depending on how one interprets these verses. Ray allows for eight (based on

the “heads of families” in Numbers 26), Keil and Delitzsch up to nine or ten (Pentateuch, 2:30).

18

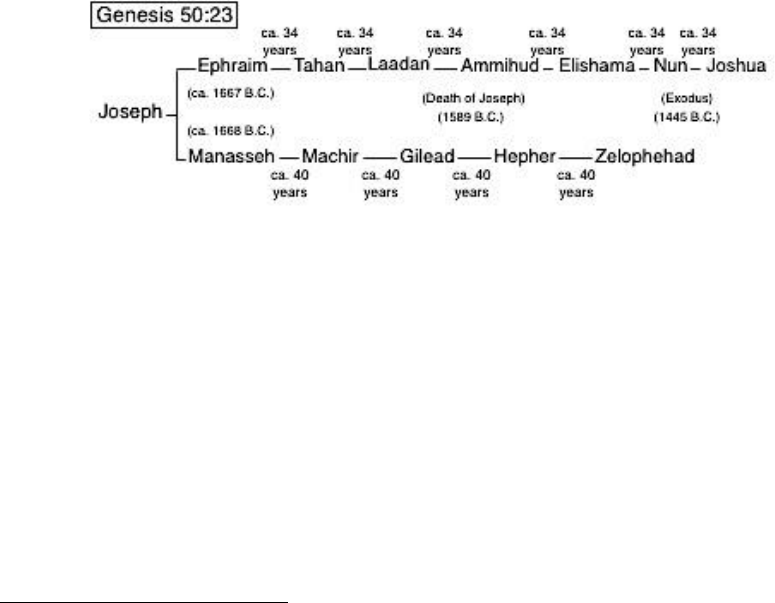

the death of Joseph and birth of Moses; however, Genesis 50:23 seems to imply

otherwise. “Joseph saw Ephraim’s children to the third generation. The children of

Machir, the son of Manasseh, were also brought up on Joseph’s knees” (NKJV). Ephraim

would have been born ca. 1667 BC according to the 215-year theory (see Gen. 41:50–53;

45:10, 11), which is about 78 years before the death of Joseph. Should this trajectory be

maintained, it is very possible for Joshua to have been called “a young man” (Heb. רענ

Ex. 33:11) by the time he served Moses at Sinai. One of Machir’s sons was Gilead (Josh.

17:3), and Gilead’s grandson was Zelophehad, who died during the wilderness

wanderings (Num. 27:1–3). If Gilead was born prior to 1589 BC (i.e. the year of Joseph’s

death), then this accords well with the 215-year sojourn, while being very difficult for a

430-year sojourn, as demonstrated by the following figure:

34

Ray made the point that Aaron’s marriage to Elisheba, Nahshon’s sister (Ex. 6:23)

is also indicative of missing generations in Aaron’s and Moses’s family tree.

35

However,

simply because Aaron is supposed to belong to the same generation as Ram (his wife’s

grandfather) does not necessarily demonstrate incompleteness in the genealogies: Hezron

(Elisheba and Nahshon’s great-grandfather) is recorded as taking a wife from Machir’s

34

Both Ephraim and Manasseh are said to have been especially blessed with “fruitfulness,” and Ephraim

more so (Gen. 48:13–20; 49:22, 25).

35

Ibid., 248.

19

children (the supposed equivalent of his children’s generation) at the age of 60 (1 Chron.

2:21). All of the aforementioned information drawn from biblical genealogies tends

toward the same conclusion: a 215-year sojourn in Egypt is upheld strictly on the basis of

genealogies throughout the Old and New Testaments. Either there are missing

generations in the genealogies of Moses, Aaron, Korah (1 Chron. 6:18–22), Zelophehad,

David, as well as others, or there are none missing at all.

Despite some difficulties, strong arguments are made for the 430-year sojourn

aside from genealogical information, and well-thought reasons may still be given to

dismiss the “fourth generation” argument based on Genesis 15:16. The argument is

presented that the Hebrew ר (dôr,“generation”) originally carried the connotation of a

lifecycle.

36

In the days of Abraham, who was about 100 years old when he bore Isaac, a

“lifecycle” could be perceived as approximately 100 years; this would give Genesis 15:16

the meaning, “in the fourth cycle of one hundred years” rather than a literal fourth

generation.

37

Alternatively, the term dôr in this context could refer to the “lifecycles” of

Levi (137), Kohath (133), and Amram (137) added together, amounting to about 407

years. It seems worth mentioning that there exists no Jewish source or tradition that has

ever interpreted dôr in this manner to support a 430-year sojourn.

38

Lastly, a heretofore

unchallenged argument that makes for a strong case may be pointed out in Numbers 3:27

36

R. Laird Harris, Gleason Leonard Archer, and Bruce K. Waltke, Theological Wordbook of the Old

Testament (Chicago: Moody Press, 1980), entry 418c.1.

37

D. N. Freedman and J. Lundbom, “Dôr,” in Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament, vol. 3 (Grand

Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1978), 170, 174.

38

Josephus contradictorily mentions 400 years in Egypt (Ant. 1.10.3; 2.9.1), yet also supported the 215-

year sojourn in Ant. 2.15.2 and Ag. Apion 1.14. Rabbinic tradition insists on a short sojourn of 210 years in

Egypt (see Edgar Frank, Talmudic and Rabbinical Chronology [New York, 1956], 11, 19; H. H. Rowley,

From Josephus to Joshua [London, 1950], 67–69; Rashi, Pentateuch with Rashi’s Commentary, vol. 1, ed.

Am. M. Silbermann and trans. M. Rosenbaum and Am. M. Silbermann, [London, 1945], Part 1, 61–62, and

Part 2, 61).

20

and 28; the text apparently suggests that there existed an impossible number of male

“Kohathites” (8,600) at the time of the Exodus, presumably one fourth of which (2,150)

were of Amram—an outrageous number to be distributed between Moses’s and Aaron’s

families alone.

39

This point will be discussed in the following section.

Multiplication of Israel’s Descendants

Perhaps the strongest reason in favor of all 430 years having taken place entirely

in Egypt is the incredible multiplication of the Israelite people asserted in Scripture.

Exodus 12:37 states that “about six hundred thousand men on foot, besides children”

(NKJV) left Egypt ca. 1445 BC. Genesis 46:27 records a mere 69 people of blood

relation to Jacob entering Egypt. Naturally, it is difficult to accept this multiplication in

such a short amount of time as 215 years. Keil and Delitzsch count 41 grandsons

recorded in Genesis 46 that produced sons of their own; 10 or 11 generations of 40 years

each are considered in the calculations for a 400-year sojourn.

40

A conservative estimate

of three sons and three daughters are reckoned for the first six generations, while the

remaining four hypothetically had two sons and two daughters—the result by the 10

th

generation is 603,550 males.

A case, though far more unlikely, may also be made for this same multiplication

being possible during a 215-year sojourn in Egypt. As already mentioned, patriarchs like

Amram lived for a total of 137 years (Ex. 6:20)—this could amount to as many as five or

even six or seven generations living contemporaneously due to the remarkable longevity

avowed at this point in biblical history. For the following calculations, it must be kept in

mind that men like Moses and Aaron are part of the elder generation, and may be

39

Keil and Delitzsch, 1:470.

40

Ibid., 28–29.

21

considered somewhat of an exception regarding the ages of their forefathers at the time

they begot their firstborn sons (in other words: while other tribes of Israel were

multiplying rapidly, Amram was born “late” in Kohath’s life and begot Aaron and Moses

also rather “late” in his life). Aaron, being 83 years of age at the time of the Exodus (Ex.

7:7), undoubtedly had adult sons and grandsons (Num. 25:7, 8). Phinehas’s children or

even grandchildren may have been born before the Conquest and are simply not

mentioned in the Pentateuch. Additionally, incomplete records of siblings of the same

generation are equally likely in many cases as potentially unrecorded ancestors or

“missing generations.” For many persons mentioned in the Pentateuch, or all Scripture

for that matter, it is not impossible that there may be a great many unmentioned brothers

or sisters.

Although straining credulity, it is still theoretically possible for the kind of

immense multiplication described in the biblical account to have taken place within the

framework of a shorter sojourn, particularly towards the end of the 215-year period

allotted. Great population growth is recorded when Jacob first entered Egypt (Gen.

47:27), after Joseph’s death (Ex. 1:7), after the Israelites were enslaved (Ex. 1:12), and

after the first Egyptian efforts at population control (Ex. 1:20); the Israelites are recorded

as being numerous throughout the land just prior to the Exodus (Ex. 5:5), even though

many newborn males were killed approximately 80 years before. Exodus 12:37 has

already been cited for a rough number of male Israelites at the time they left Egypt;

Numbers 1:1–47 records a census taken at Mount Sinai in the second year after the

22

Exodus, with a total of 603,550 males above age 19.

41

It should be emphasized that the

census of the Levites in Numbers 3, quoted by Keil and Delitzsch (and, by extension,

Paul Ray Jr.), calculating 8,600 Kohathites (v. 28) does not refer to males age 20 and

above, but actually to males “from a month old and above” (v. 15, NKJV). It is

unwarranted to estimate 2,150 males for the Amramites: if every female Izharite,

Hebronite, and Uzzielite bore 10 children (perhaps a rather outlandish scenario), 8,600

male Kohathites could nevertheless be entirely accounted for within the time allotted

based solely on these three family lines, irrespective of the Amramites. The biblical

record is silent as to how many children Aaron’s offspring had produced by this time,

excepting Phinehas, and it is wholly unknown whether Aaron had great-grandchildren or

even “great-great-grandchildren” born among the Amramites. It would also probably be

the case that many of the 8,600 Kohathites would be quite young, as a population

“explosion” of sorts could have occurred relatively near the time of the census, and

would help the plausibility of this nearly impossible case.

Several other factors that ought to also be included are passages within the corpus

of Scripture that have not heretofore been considered. For example, though Keil and

Delitzsch factored six children in total for a given Israelite family, 1 Chronicles 4:27,

speaking of a relatively proximate descendant of Simeon (of perhaps the fourth

generation), states “Shimei had sixteen sons and six daughters; but his brothers did not

have many children, nor did any of their families multiply as much as the children of

Judah.” Even if having 22 children was considered to be an exception to the norm, this

41

Numbers 26:1–51 records a second census that took place at the end of the time of “wilderness

wandering,” ca. 1405 BC, and allows for a population comparison during the 40 years—601,730 males age

20 and above.

23

text appears to attribute to the tribe of Judah exceptional multiplication indeed.

Furthermore, multiple wives were often involved in achieving such population-expanding

feats, as in the cases of Jacob (who begot 10 children in 7 years, Gen. 29:31–30:24), Esau

(Gen. 28:9), Judah (Gen. 38:1–12, 24–26), Caleb the son of Hezron (1 Chronicles 2:18,

19), etc. Additionally, in 1 Chronicles 2:21–24, Hezron is said to have taken a wife after

his son had married, remarried, and begot children (note that v. 21 says “Now

afterward…” NKJV), and at the age of 60 no less—there even seems to be indication that

Hezron was impregnating his wife/wives even until his death: ‘After Hezron died in

Caleb Ephrathah, Hezron’s wife Abijah bore him Ashhur the father of Tekoa” (v. 24).

These instances, though incredible, should be kept in mind when attempting to consider

the possibility of a 215-year sojourn.

There are some fascinating modern examples that, though nearly unbelievable,

demonstrate the astonishing possibilities of generational multiplication. One Edward G.

Martin of Ontario, Canada, is recorded to have produced through six children a total of

91 grandchildren, 337 great-grandchildren, and 15 great-great-grandchildren before his

death in February 5, 2006 (predeceased by one son, two grandchildren, 10 great-

grandchildren, one great-great-grandchild; aged 102). Born in November 1903, Rev.

Martin produced a total of 463 descendants in his lifetime.

42

Remarkably, according to

international news sources, it is claimed that Nigerian preacher Mohammed Bello

Abubakar fathered as many as 203 sons by way of extensive polygamy before his death

in 2017, aged 93.

43

Lastly, Yitta Schwartz, of the Satmar Hasidic sect of Judaism, birthed

42

Public records accessed 2/12/2019,

http://generations.regionofwaterloo.ca/getperson.php?personID=I170124&tree=generations.

43

“Nigerian faces death for 86 wives,” BBC News, August 21, 2008,

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/7574757.stm; “Nigeria: Former Muslim preacher with 130 wives dies at

24

15 children, producing over 200 grandchildren and amounting to approximately 2,000

descendants by her family’s count, before passing away at the age of 93.

44

Were each of

Jacob’s 41 grandchildren to have accomplished a similar feat, more than 80,000

descendants would have filled Goshen by the first half of the sojourn in Egypt. It

therefore enters within the realm of possibility that about 600,000 male descendants

could have left Egypt after only 215 years—but just barely.

Conclusion

The primary reasons for holding to a 430-year Egyptian sojourn can be

summarized as (a) a literal reading of Exodus 12:40 and Genesis 15:13, 14; (b) the

reliability of the MT reading underlying these texts; and (c) the unlikelihood of the

Israelite multiplication taking place in only 215 years. The main reasons for maintaining

a 215-year sojourn in Egypt are (a) an equally literal reading of Genesis 15:16 and the

genealogy of Moses; (b) the testimony of Paul the Apostle (and for Seventh-day

Adventists, of Ellen G. White); and (c) the testimony of LXX and SP manuscripts and

other early Jewish sources. Although the 430-year theory is ostensibly far more realistic,

both the 430- and 215-year theories are technically possible, and both ought to be

considered viable positions in the greater study of biblical chronology. Perhaps it was

stated best by Thiele when he wrote, “On the basis of the Old Testament data it is

impossible to give a categorical answer as to exactly what was involved in the 430-year

sojourn, nor is it possible to give an absolute date for Abraham’s entry into Canaan.”

Ultimately, unless new or more conclusive data can be obtained, all that can be offered is

93,” The Indian Express, January 31, 2017, https://indianexpress.com/article/world/nigeria-muslim-

preacher-with-130-wives-dies-at-93-4500043/.

44

Joseph Berger, “God Said Multiply, and Did She Ever,” New York Times, February 21, 2010,

https://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/21/nyregion/21yitta.html.

25

a presentation of all the evidence and arguments involved, and the final conclusions will

have to be determined by the readers, as they deem most probable.

26

Excursus

James Hoffmeier cites a total of 633 years that seemingly need to have taken

place within the 480 years allotted in I Kings 6:1, between the Exodus and the building of

the Temple.

45

There are several factors that have been failed to be considered in this

estimation: for example, that the 40 years of the Philistine oppression (Judg. 13:1) and the

20 years of Samson’s judgeship (Judg. 15:20) are in reality overlapping events.

46

Although admittedly statements that “the land had rest” and that “the country was quiet”

for a specified number of years (Judg. 3:11, 30; 8:28), as well as the phrase that for the

prior judge a succeeding judge would arise “after him” (Judg. 3:31; 10:3; 12:8–13),

seemingly indicate a non-consecutive chronology, there are more reasons that suggest

that there was overlap within the chronologies recorded in the book of Judges.

The events in the book of Judges can be clearly demonstrated to have been written

in a non-sequential order (at least chapters 19 through 21 are recorded to have taken place

under the priesthood of Phinehas, who was alive at the time of the Exodus, Judges 20:28).

Additionally, Judges 17 and 18 describe an event that probably took place during the life

of Joshua (see Joshua 19:40–48, Judg. 18:27-31).

47

Furthermore, the text suggests that

45

James Hoffmeier, “What is the Biblical Date of the Exodus: A Response to Bryant Wood,” Journal of the

Evangelical Theological Society 50 (2007): 227.

46

It is described in Judges 13:1–5 before the birth of Samson that God’s intention for him was that he

would “begin to deliver Israel out of the hand of the Philistines” (v. 5, NKJV). Samson ostensibly

accomplishes this in his dying act in chapter 16, where it is stated that the length of Samson’s judgeship at

the time of his death was 20 years (v. 31); it seems more probable that Samson ended the 40 year Philistine

oppression at his death, which would be the end of his 20-year judgeship, not the beginning of it.

Furthermore, the Israelites were not fully delivered “out of the hand of the Philistines” until the days of

Samuel—their freedom from oppression stemming from this people group being ultimately realized

through David (see I Samuel 4:1–11; 7:2–14; II Samuel 5:17–25; I Chronicles 14:8–17). From a Seventh-

day Adventist perspective, it is interesting to note that Ellen White corroborates that Samson was born in

“the early years of the Philistine oppression” (Patriarchs and Prophets 560.1).

47

LXX and Latin Vulgate read “Jonathan the son of Gershom, the son of Moses” was the priest for the

Danites at this time, being a grandson of Moses rather than a grandson of Manasseh as in MT. Being a

difference of a single letter (Nun) in Hebrew, this might furthermore corroborate an earlier date for this

event having taken place.

27

judges seem to have been somewhat localized to specific areas (e.g. Samuel, I Sam. 7:15–

17; Deborah, Judg. 4:4, 5; perhaps Tola, Judg. 10:1), and that the oppressions themselves

seemed to be localized to a certain degree, affecting only certain tribes in certain

geographical locales (e.g. Judg. 10:8, 9). The chronological picture is complicated further

by the fact that there were other oppressions that were not described at length (Judg.

10:11, 12), as well as judges that were never recorded to have personally fought battles to

provide deliverance from oppression at all (Judg. 10:3; 12:8–15; I Sam. 4:18; 7:15).

(Additionally, it is interesting to note that there were also judges that “delivered” but

were not ever recorded to have specifically “judged” for a given length of time—e.g.

Ehud, Gideon, Shamgar, etc.) There is also at least one mention in Judges 3:31 of what is

either an example of a concurrent oppression, a sort of “preventative deliverance,” or else

an altogether unmentioned oppression. It is also possible that in the chronological

reckoning there is rounding of years, or perhaps to the nearest decade. All this suggests

that there is overlap in the book of Judges, that there is nothing biblically contradictory

with an early date for the Exodus, and that the remarkable internal consistency of the

Bible as a whole may be upheld.

28

Bibliography

Albright, William F. “Archaeology and the Date of the Hebrew Conquest of Palestine,”

BASOR 58 (1935): 10–18.

---------. “Further Light on the History of Israel from Lachish and Megiddo,” BASOR 68

(1937): 22–26; idem, “The Israelite Conquest of Canaan in the Light of

Archaeology,” BASOR 74 (1939): 11–23.

Anstey, Martin. The Romance of Bible Chronology (London: Marshall, 1913), 116–18.

Archer, Gleason Leonard. A Survey of Old Testament Introduction, Rev. ed. (Chicago:

Moddy Press, 1974), 205, 211–12.

Bliss, Sylvester. Memoirs of William Miller (Boston, MA: Joshua V. Himes, 1853).

Cooper, David L. Messiah: His First Coming Scheduled (Elsternwick, Victoria: Bible

Research Society, 1945), 129–34.

Dorival, G., M. Harl, and O. Munnich, La Bible grecque des Septante: Du judaïsme

hellénistique au christianisme ancient (Paris: Éditions du Cerf, 1988), 111.

Frank, Edgar. Talmudic and Rabbinical Chronology (New York, 1956) 11, 19.

Freedman, D. N. and J. Lundbom, “Dôr,” Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament,

vol. 3 (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1978), 170, 174.

Harris, R. Laird, Gleason Leonard Archer, and Bruce K. Waltke, Theological Wordbook

of the Old Testament (Chicago: Moody Press, 1980).

Hoehner, Harold. “The Duration of the Egyptian Bondage,” Bibliotheca Sacra 126, no.

504 (1969): 306–16.

Hoffmeier, James K. Israel in Egypt (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996).

29

---------. “What is the Biblical Date of the Exodus: A Response to Bryant Wood,” Journal

of the Evangelical Theological Society 50 (2007): 227.

Keil, K. F. and F. Delitzsch, The Pentateuch, vol. 1–3, trans. James Martin, in Biblical

Commentary on the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: 1952).

Kitchen, Kenneth A. Ancient Orient and Old Testament (Chicago: Inter-Varsity Press,

1966).

---------. Pharaoh Triumphant: The Life and Times of Ramesses II, King of Egypt

(Warminster, England: Aris & Phillips, 1982).

Larsson, Gerhard. “The Chronology of the Pentateuch: A Comparison of the MT and

LXX,” Journal of Biblical Literature 102, no. 3 (1983): 401–09.

Mauro, Philip. The Chronology of the Bible (New York: George H. Doran, 1922), 37–40.

Nichol, Francis D. The Seventh-day Adventist Bible Commentary (Washington: Review

and Herald, 1953).

Peet, Eric T. and J. W. Jack, “The Date of the Exodus,” The Journal of Egyptian

Archaeology 12, no. 3/4 (1926): 322.

Ray Jr., Paul J. “The Duration of the Israelite Sojourn in Egypt,” Andrews University

Seminary Studies 24, no. 3 (1986): 231–48.

Rowley, H. H. From Josephus to Joshua (London, 1950), 67–69.

Shea, William. “Exodus, Date of,” International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, vol. 2, ed.

Bromiley (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1985), 232.

Steinmann, Andrew E. From Abraham to Paul: A Biblical Chronology (St. Louis: MO:

Concordia, 2011), 68–70.

30

Thiele, Edwin R. “The Chronology of the Kings of Judah and Israel.” Journal of Near

Eastern Studies 3, no. 3 (1944): 137–86.

---------. “Chronology, Old Testament,” The Zondervan Pictorial Bible Dictionary, ed.

Merrill C. Tenney (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 1967), 166–67.

Tyldesley, Joyce A. Ramesses: Egypt’s Greatest Pharaoh (New York: Penguin, 2001).

Unger Merrill F. Archaeology and the Old Testament (London: Pickering & Inglis,

1964).

Vanderkam, James C. “Questions of Canon Viewed through the Dead Sea Scrolls,”

Bulletin for Biblical Research 11, no. 2 (2001): 273–74.

Wood, Bryant. “The Rise and Fall of the 13

th

Century Exodus/Conquest Theory.” Journal

of the Evangelical Theological Society 48 (2005): 479.