1

When Disability Strikes

By Renée Bondi

As I rolled into the ballroom at the Hyatt Regency Hotel in Irvine, California, I couldn’t escape the irony.

In that very room, 11 years earlier, I had danced the last dance of my life with my fiancé, Mike. I was the

happiest woman on earth that night. There was no way I could have imaged that within 36 hours my

life would be turned upside down—never to be the same again. Waiting for my name to be announced

to accept the Goodwill Industries Walter Knott Service Award for Overcoming Disabilities, I looked

around and reflected on how different my life was now from my dreams on that night so long ago.

Sometimes our lives take turns we wouldn’t choose. Mine certainly did.

Years before, the ballroom had been decorated for the San Clemente High School Prom. I was a

29–year-old choir teacher. Our vocal music program had grown from only 18 students during my first

year to 150 students just a few years later. I had always been passionate about the arts and was blessed

to be able to merge my passion with my career. And I was about to marry my best friend—the love of

my life. The wedding was just two months away.

That Saturday, May 15, 1988, Mike flew into town for business and to be my date for the prom.

Mike was living in Denver, working for Lockheed Martin. We were prom chaperones and I was as excited

as the high school girls. Since I hadn’t seen Mike in four weeks, I’d looked forward to the evening.

We went to dinner at the Velvet Turtle, one of our favorite restaurants. During the entrée, he looked at

me mischievously, reached in his pocket and handed me my engagement ring! Mike slipped it on my

finger, and it fit perfectly.

When we weren’t busy with our chaperoning duties, Mike and I danced in each other’s arms. Danc-

ing was almost as important to me as singing. It was a storybook, romantic evening. But we never

danced together again.

Great Was the Fall

The next morning, Mike flew to Denver. I went to pick up my bridesmaids’ dresses and gifts. The spring

musical was that afternoon, and I conducted the orchestra for a packed auditorium. The performance

was wonderful, the audience enthusiastic, and the actors and musicians proud. It was a banner day.

I didn’t make it home to the condominium I shared with a roommate, Dorothy, and her daughter,

until around 7 p.m. After dinner, I wrote some lesson plans and went to bed about 11 p.m.

I woke up out of a deep sleep, in mid-air thinking, Huh? Then I finished a flip off of my bed and landed

on the top of my head. BOOM! My feet were in the closet and my head was against the dust ruffle.

Still half asleep, it didn’t occur to me to wonder why I had dived off the end of my bed or if I was

really hurt. My only thought was to get back in bed. Rolling over onto my left shoulder, the right side

of my neck went CRACK! Oh, man! A pain jolted me back down. I rolled onto my right shoulder, and

the left side of my neck went CRACK! Oh, man! Again, the excruciating pain threw me back down. I re-

alized I needed help getting up. My roommate’s bedroom was upstairs, so I knew I’d have to be loud

to wake her up. Taking a deep breath, I tried to yell, “D o r o t h y!” But it was only a whisper. Come on,

I thought. You’re a singer; you teach breathing! So I took a breath from way down deep and tried again:

“D o r o t h y!” There was no improvement.

About the same time I was falling, Dorothy woke up—DING! She sat up in bed with a jolt for some

unknown reason. She thought she’d heard a voice. Getting out of bed, she walked to the stairs to see

if I was on the phone. I heard Dorothy’s voice calling, “Renee,” and her footsteps on the stairs, then

her hand on the doorknob. When she opened the door, I breathed a sigh of relief. Seeing me flat on

my back, she asked, “Why are you lying on the floor? It’s 2 o’clock in the morning!”

“I don’t know,” I responded in a whisper. “My neck is killing me. I don’t know what I did. I can’t

get up. Go call the paramedics.”

Dorothy stared at me for a moment and then picked up the phone to call 9-1-1. All of a sudden,

the strangest sensation came over my body. The only way to describe it would be as a wave, maybe a

wave of silence. Starting at my neck, I felt WHOOOOOOOSH as a wave slowly rippled from my neck…

WHOOOOOSH… down to my toes. What on earth was that? I thought. I can’t be paralyzed! All I did was go

to bed! No way! Although the thought did cross my mind, I couldn’t imagine I was actually paralyzed.

Looking back, however, I now firmly believe that the undulating wave was the onset of paralysis because

I never moved again.

To this day, we don’t know what caused me to dive off the end of my bed in the middle of the

night. Perhaps I dreamt that I was diving into a pool. Another idea came from a woman who heard

me tell my story during a concert in Wisconsin a few years back. She said a similar thing happened to

her friend and the cause was traced back to methyl methacrylate, a chemical used to apply acrylic fin-

gernails in the 1980s. In some cases, the chemical went through the cuticle into the bloodstream caus-

ing hallucinations or seizures. The week before my injury I had acrylic nails put on for the first time.

Unfortunately, I met this woman 15 years after my injury and by that time the chemical was no longer

in my system. In my heart of hearts, I believe that chemical is what caused my paralysis.

Initial Denial

After Dr. Palmer, the neurosurgeon, delivered the revolting news that I would never walk again, he said,

“I’ll let your family come in now.” He left and I was alone for a few minutes, trying to process what

he’d said. Simply put, I didn’t believe him. I was in total denial. It was as though there was a fog hovering

over me and everything seemed inconceivable, impossible. How could I have been dancing with Mike

just two nights before and now be permanently paralyzed? It just didn’t make sense.

Mom and Dad came to see me first. When I saw the depth of sadness and seriousness on their faces,

it was apparent that they did believe Dr. Palmer. They couldn’t muster the effort to cheer me up or as-

sure me that everything would be okay. Mom touched me and asked how I felt. It was really awkward.

My sisters and brother had the same expression—one of disaster.

Mike’s father called him and he immediately flew home. When he entered the ICU, he walked over,

put his cheek against mine and said, “Hi, honey. I’m here.” I looked up into his broad smile. I tried to

smile and whispered, “Well, I guess the good news is that now we’ll get the really good parking places.”

When D isab i lity Strik e s, By Renée Bond i

2

Mike laughed out loud! Later, he said that in that moment he knew we’d be okay because although

my body was broken, my personality and sense of humor were still intact.

After spending almost two weeks completely prone, it was time for the cardiac chair. A nurse and

a physical therapist would transfer me to the cardiac chair, positioned flat, like a gurney. I felt like a

Raggedy Ann doll, flopping to the left and right, or forward in the blink of an eye. They had to strap

me on at the chest, waist, and legs, so I wouldn’t fall off. I hated to be moved because any jostling trig-

gered the pain in my neck all over again.

They would crank up my back to about a 45-degree angle, and then we’d sit and wait to see if my

blood pressure would adjust to the new position. If that worked, they’d lower my feet and legs to

45 degrees, and, again, sit and wait. When my head was elevated and my feet were lowered, the blood

tended to pool in my legs because my body was not strong enough to pump it back up. When that

happened, I would either throw up or pass out, so at the first hint of discomfort, they’d take me back

to the prone position and start all over again. It was incredibly discouraging to realize how difficult

it was just to sit up, something people do without even thinking.

Getting to Work

I spent five months at Long Beach Memorial Hospital for inpatient physical therapy. A typical day started

with breakfast at 8:00, followed by getting dressed and in my wheelchair by 9:00, no easy feat. I’d roll

down the hallway to the physical therapy gym. Considering the shape I was in, I really needed someone

to make me laugh, and my physical therapist did! But she also made me work. In one exercise, she would

place my feet squarely on the floor and then hold me up in a seated position. Next, she would put my

arms behind me and prop me up like a picture frame so that I would learn to balance while sitting up.

It was weird trying to sit on my bottom when it felt numb, and prop up on my arms when they felt like

they were asleep. I also had to learn to find the center for my head. The head is heavy, and if my head

was off to one side I’d topple over. The only place on my torso where I had movement was my shoulders,

so I did thousands and thousands of shoulder shrugs with my physical therapist applying resistance.

Then I’d move on to occupational therapy. There was a contraption that came up over my head

and had strings that came down and attached to troughs on both sides. They put my arms in the

troughs, trying to train my shoulder muscles to direct my arms. I would do my shoulder shrugs to get

my arms to move, but my appendages flailed out of control. The occupational therapist would attach

a writing brace to my wrist, insert a pen, and place a piece of paper before me. “Now, Renée, just see if

you can mark anything—a line or scribble—just get the pen on the paper.” It was one of my first reality

checks. I had no control, not even a hint of muscle that would allow me to aim the pen or create enough

pressure to even make a mark. Tears spilled out of my eyes. “I can’t even write; I can’t even sign my

name!” But after a few minutes of sorrow, I’d shake it off and tell my therapist, “Okay let’s keep going.

Let’s just keep going.”

Physical and occupational therapies were my lifelines. I did therapy five days a week and had week-

ends off. I hated the weekends because I felt like we were wasting time. The weekends actually scared

me because I wasn’t making progress. I wanted to work seven days a week, because each day I worked

meant I was a day closer to walking, to returning to normal life again. At the time, I had a female room-

mate who would refuse her therapy sometimes. I couldn’t understand. After all, lying in bed would not

make you better. I came to realize that she couldn’t imagine living a life so dramatically different, and

more difficult. For her, the mountain seemed too steep to climb. In the first year, the steps forward

seem so very, very small that the patient feels they can’t make it to the top. So why try?

When D isab i lity Strik e s, By Renée Bond i

3

I remember a friend coming to visit me in the hospital at the end of the day. I was out in the hospital

patio getting fresh air after therapy. When she saw me outside, sitting up, she exclaimed, “Wow! How

great that you are out here!” All I could think was, “Big deal, so I made it outside. Whoop-dee-doo!”

I never got as excited over the baby steps as my family and friends did. They were just that, baby steps,

and I was no baby. Later, I realized the importance of those small accomplishments, but at the time

they seemed insignificant.

Who Am I?

The other huge concern was my sense of identity. I would think to myself: Who am I now? I knew who I

was when I was running around, but now? One day I was being taken from therapy back to my room and

I saw a mirror. “Stop!” I said to the orderly. “Can you turn me so I can look at myself?” It was the first

time I had seen myself in a mirror since the accident. I had the halo on. The metal hardware surrounded

my head and chest to keep my neck perfectly still in order for it to heal. I looked into the mirror and

made faces. Those are my eyes. That’s my nose. I’ve lost weight; I like it, looks good. Ooohh, but my hair. I hate the

way they’ve combed it back with no bangs. So this is what my visitors see when they come; they have to look through

all this hardware. I smiled at myself in the mirror, studied me, analyzed myself. Okay, it’s still me. Then I

said to the orderly, “Okay, I’m ready. Let’s go.” It’s funny; sometimes it’s good to stop and take stock

and consider not just what has changed but also what has remained stable. Whenever life seems to be

falling in around us, it can be reassuring to realize that never is everything lost.

Release to Prison

The day I left the hospital was one of the saddest days of our lives. Mike and I had both thought, had

expected, had hoped, that I’d walk out of Long Beach Memorial. Instead, I rolled out in my sip-n-puff

wheelchair. No more denial. This was it. I knew that, outside of a miracle, I’d never walk again. I realized

I would always be dependent on someone else to take care of my needs. I’d never drive a car, or ride a

horse, or sing, or teach again. With Mike’s hand on my shoulder, I cried all the way home.

Fear. Were we really ready for this? Could we really pull this off? The hospital had been safe. Not

fun, but safe. I knew what the schedule was each day, and I had trained professionals taking care of my

needs. It was their business to anticipate problems and to prevent them. If there was an emergency,

I knew that within seconds I’d be surrounded by hospital personnel who knew just what to do. Plus,

in the hospital, I didn’t have to face the “normal” world. During that first year, I could not be left alone.

I had to be physically put to bed and taken out of bed. I had to be bathed and dressed. My teeth had to

be brushed and my hair combed. Someone had to prepare my food and help me eat. If I needed some-

thing, someone had to bring it to me. I couldn’t go anywhere unless I was driven, and I had physical

therapy three times a week. It was like taking care of a 30-year-old baby! It was an enormous, time-con-

suming obligation. While my family wanted to be there for me, they had lives, families, and jobs of

their own.

Now What?

Places where I had walked and run, I now had to roll, and as I rolled by, people naturally looked my

way. I felt like I was on display. I was an oddity—no longer part of the normal landscape. Some well-

meaning observers would give me the oh-you-poor-thing look, which I hated. However, most adults

When D isab i lity Strik e s, By Renée Bond i

4

would generally glance and then look away. Children didn’t. They were openly intrigued by the woman

in the ugly contraption and wondered how it worked. I wasn’t comfortable with myself, but I tried to

make others as comfortable as I could by answering their questions and demonstrating my sip-n-puff.

As a result, I ended up spending most of my time in our condo. Occasionally, we would go out to

eat or to the mall. On these trips I felt very self-conscious, so I’d keep my eyes straight ahead. I didn’t

want to see the looks and stares as I went by. I loved it when my sister brought Brent, her darling three-

year-old son. I’d always want him to ride on my lap. I felt like his body concealed mine, and he was so

cute that people looked at him and not me.

New emotions became part of my personality. For example, one Saturday, not long after I’d gotten

home, Mike took me out for a spin in his little red Acura Legend. “Mike,” I said. “I haven’t had ice

cream in forever. Could we stop at Baskin Robbins?”

“Sure!” So he whipped into the parking lot in front of 31 Flavors. Obviously, it wasn’t worth the

trouble to transfer me into the chair just for a quick trip into the ice cream shop. “I’ll be right back,”

he said, and disappeared.

This was the first time since the accident that I had been left alone in the car in a public place.

Suddenly my imagination went berserk. Realizing how absolutely defenseless I was, I began to imagine

all sorts of assaults directed at me. What if some man tries to open my car door and kidnap me or molest me?

Or, what if someone jumps in the car and starts to drive away with me in it? What if someone just reaches in and

yanks me out onto the pavement and steals the car? Every person who walked by became a potential attacker.

Like a whirlwind, a sudden awareness of my complete vulnerability gripped me and sent me reeling

into a state of pure, out-of-control panic. By the time Mike returned, I was shaking and my eyes were

full of fear. His tight embrace and words of comfort calmed my heart, making me feel safe once again.

Effects of Dependency

By far the most difficult part of being quadriplegic is the dependence on others for daily activities.

If I had any denial regarding my paralysis, receiving help from a caregiver for my most basic needs—

like bathing, dressing and eating—forced me to face reality. This triggered several emotions:

Overall sense of unworthiness – I felt completely unworthy to be Mike’s wife. What could I do

for him? How could I go grocery shopping and make him dinner? How could I give him chil-

dren? How could I show him my love? How could I raise a child? Because I could not return his

love in tangible form, I felt unworthy of his love. Not only did I feel this way toward Mike, but

equally so with his parents and siblings. I knew that Mike had made the decision to stay with

me, but I couldn’t imagine they were in agreement. I was scared for my future in-laws to see

how difficult our life had become. Being a burden to them, my parents, siblings, neighbors and

friends, I ultimately felt unworthy of anyone’s love. After all, if you are always the taker in the

relationship and never the giver, you feel unworthy of their friendship.

Embarrassment – it was humiliating to have someone see me naked, sitting in a shower chair.

One of my high school students became my weekend attendant. Imagine how embarrassing it

was to have her see me naked and wash my private parts.

Humiliation – I no longer had control of my own body. One day I was sitting at my kitchen table

with my goddaughter, Marne Andersen. I began to smell a strong, pungent odor. I tried to ignore

When D isab i lity Strik e s, By Renée Bond i

5

it for a while, but it became too obvious to ignore. I discreetly moved my wheelchair around to

see if I was having a bowel problem. Much to my horror, there was a small brown puddle under

my chair. I had a bowel accident. No one was around but my teenage goddaughter. Humbly, I

told her my situation and we cut our time short so that I could phone my sister for help.

Frustration – total dependence on others is draining. From trying to describe which blouse you’d

like to wear, or which book you want from the 200 on the shelf, or what tax document you are

looking for—finding just the right words to convey your thoughts can be extremely trying. Many

times it looks as though the disabled person is frustrated that the caregiver or spouse cannot

do the right thing, when in reality, they are irritated by their inability to explain their need. An-

other example is rolling out to the parking lot to find someone parked over the stripes, en-

croaching on the handicap stall. It becomes impossible to get in your vehicle, requiring the

person in the wheelchair to wait, sometimes for hours, until the other driver returns. Also, prior

to my accident, I never realized what a privilege it was to drive in the car alone. Time to think

through the meeting you are about to attend, or what items you need at the market, or the

words to say to an ill friend—I took it for granted. When one is dependent on others for trans-

portation, it is difficult to say, “Please stop talking so I can think about what is coming up.”

Some people would suggest, “Just say it!” But in reality, it’s hard to do.

Anger – frustration can multiply a thousand times. A young disabled person can feel anger that

they’re not able to participate in school or sporting activities like other children. He or she might

be resentful that a sibling can go to the beach with a friend or ride their bike to the park. As an

adult, I was very angry about the fact that I had to have my mother around to help me. After all,

I was an adult. It was not my mother who made me angry, but rather what she symbolized. I

didn’t want to still need my mother at 30, 40, or even 50 years old. When she came to help with

dinner or laundry, I would get angry because her presence was a reminder of my dependence and

the reality that I had not been able to experience the natural shift from child to adult. I tried

hard not to show my anger. Sometimes I succeeded, and at other times I failed miserably.

Financial Strain

Beyond the requisite attitude adjustments, the cost of paralysis is substantial and never ending. One

is forced to wonder where the money will come from for attendant care. If the disabled person is a can-

didate for money from the state, he or she gets a different caregiver every day. It is extremely difficult

to have someone new each day when it’s necessary to explain activities such as how to carefully transi-

tion from the bed to the wheelchair, or how you prefer your hair to look, or even where to find the

trash bags.

More often than not, the disabled person is not eligible for state aid. For example, if one works even

a part-time job, then they likely make too much money to qualify for state aid. A nagging question has

been, “How am I going to pay to get out of bed?” My husband’s salary goes toward the mortgage, food,

clothing and utilities. Where are we going to get an extra $40,000 a year to pay for my attendant care?

What if I was single and unable to work?

In my case, as God would have it, our pastor came to me soon after our wedding and offered me the

job of Youth Choir Director at our church. I took the position, with the understanding that I would

have volunteer parents to help pass out music, turn my pages and other simple tasks. The salary, however,

When D isab i lity Strik e s, By Renée Bond i

6

was certainly not $40,000! Working with the children and projecting my voice to the back row helped

strengthen my singing voice. Four years after my injury, after a tremendous amount of prayer and the

consistent use of my weakened singing voice, it had come back! Happy to hear I was singing again, a

wonderful man from our church suggested I make a recording of songs that gave me strength and hope

in the Lord. I never dreamt the recording would go beyond the walls of our church, but now, years later,

thousands have been sold. Those profits pay for my attendant care! Part of my emotional healing has

come from the fact that even though I cannot walk, my singing voice has been restored and I can help

others through their difficult times. Lamentations 3:22-23 says, “Because of the Lord’s great love we are not

consumed, for his compassions never fail. They are new every morning; great is your faithfulness.”

Disability and God

So how does one become mentally healthy and whole again after having your world turned upside

down? Decide what kind of person you want to be—positive or negative—seeking the good or dwelling

on the bad. Invite people into your life to help—set aside your pride or your perfectionism and allow

others to do things for you like driving you to appointments and helping in your home. Volunteer to

help someone else going through a difficult time—this gets our focus off ourselves and gives us fulfill-

ment from serving others. And, most importantly, Enter into communion with Christ—accepting the

peace, grace and strength that come from surrendering all parts of our lives to him. Ironically, these

four steps spell DIVE. When the temptation to dive into depression looms; stop and remember to De-

cide, Invite, Volunteer and Enter into communion with our Lord, the great Comforter and Healer.

Unworthiness, embarrassment, humiliation, frustration, and anger are all painful emotions. But

through my wheelchair I have learned that I must trust God for my provision and peace. After years of

daily surrender, I am confident that He who began a good work in me, will be faithful to complete it

(Philippians 1:6). Although I am not physically whole, the Lord will continue to use my disability, tears

and all, to draw me close to him and to serve others.

When D isab i lity Strik e s, By Renée Bond i

7

Renée Bondi is a popular speaker and recording artist. She has been featured in magazines such as Today’s

Christian Woman and Woman’s World and on various radio and television shows, including “Hour of

Power.” Renée has released five inspirational CDs and is the president of Capo Recording and the founder

of Bondi Ministries. The Evangelical Christian Publishers Association nominated her book, The Last Dance

but Not the Last Song—My Story, for the Gold Medallion Award. Among her many awards and honors is

Woman of the Year from the California State Senate and recognition for Outstanding Service to the Com-

munity from the U.S. House of Representatives. Renée has a BA in Music Education.

1

Wolfensberger's 18 Wounds of Disability

By Jeff and Kathi McNair

The following is a presentation and discussion of the “18 wounds” that persons with disabilities may experience as a

result of the actions and attitudes of society. This material is drawn from the work of Dr. Wolf Wolfensberger in his training

on “Social Role Valorization,” and has been adapted for this curriculum by Dr. Jeff McNair and Kathi McNair.

1

Wound 1: Bodily or intellectual impairment

A person is born with or develops an impairment. It could, for example, be a physical (bodily) impair-

ment, such as cerebral palsy or an intellectual impairment.

Wound 2: Functional limitation

As a result of the bodily or intellectual impairment, there are functional limitations. So, due to cerebral

palsy I may not be able to walk. Due to intellectual disability, I may not be able to balance a checkbook.

Wound 3: Relegation to low social status/deviancy

Because of my bodily/intellectual impairment and/or functional limitation, society relegates me to a

low social status, such that I am considered deviant. Society defines the normal range so tightly, that

the slightest variation outside of that normal range is considered deviant and I experience ostracism.

The church can respond by seeing people as individuals and by viewing them in terms of their gifts. By allowing people

to express their gifts, there is a greater likelihood that they will be seen as contributing to the larger fellowship. However,

even with the most disabled of persons, their presence is indispensable to the life of the larger body (1 Cor. 12:22).

Wound 4: Disproportionate and relentless attitude of rejection

Because of my bodily/intellectual impairment and/or functional limitation I experience rejection by

society and the rejection is relentless in that it occurs all the time in most social environments. Even in

the context of a faith system, harmful rejection may occur: “you sinned” may be expressed unconsciously

(unconscious rejection is still very harmful) and may be couched in terms of “positive” motives,

“we need quiet so we can worship.”

The church should counter this wound with “relentless acceptance.” We should tell people that there is almost nothing

that you could do that would cause us to reject you. This relentless acceptance would cause significant changes in the

way we do things at church, as at the moment our traditions have contributed to the relentless and disproportionate

rejection experienced by people with disabilities.

Wound 5: Cast into one or more historic deviancy roles; devalued social status causes devalued roles

or vice versa.

Thus, people can be considered as:

1. Non-human

a. Pre-human

b. No longer human

c. Sub-human (animal, vegetative/vegetable, insensate object)

d. other “alien” (non-human but not sub-human)

2. A menace/object of dread

3. Waste material, garbage, offal, excrement

4. Trivium

a. Not to be taken seriously

b. Object of ridicule

c. Joculator, jester, clown, etc.

5. An object of pity—accompanied by a desire to bestow happiness on people and associated

with the victim role. The person is “suffering.”

6. A recipient of charity

a. Ambiguous/borderline object-of-charity role; “nobility” in helping

b. Burden of dutiful caring; “cold charity”; entitled to only the minimum; should be grateful

“takers,” not “givers”

7. A child

a. Eternally

b. Once again

8. A sick/disease organism (leads to handicap); “Medicalization of everyday life”; psychiatriza-

tion of deviance

9. In death-related roles: dying, already dead, as good as dead, should be dead, should never

have lived

2

Each of the deviant role perceptions described above have been or are now present in the church. For example, people

will refer to adults with intellectual disabilities as “kids” (number 7 above), independent of their chronological age.

In each of these cases, the church should seek to do the counter—that is, the opposite—or at least make the effort not to

contribute to the kind of negative stereotyping described above.

Wound 6: Symbolic stigmatizing, “marking, deviancy imaging, branding”

Because of my bodily/intellectual impairment and/or functional limitation, I am given a label—e.g.,

“retard” or “mental age of a child”—and interactions with me cascade out of that characterization. The

church ought to be careful not to reflect society in the manner in which it deviancy-images people. Un-

fortunately, however, we are often guilty of this. For example, in California, about a tenth of one percent

Wolfen s berg er's 18 Wound s of D isabi l ity, by J e ff and K athi McNa i r

2

of Christian schools have programs for children with disabilities. How are the children of Christian

families who have a disability being imaged? They are imaged as either unworthy/unable to benefit or

as not a priority for a Christian education. That people with disabilities are not present in churches in-

dicates that they are imaged as not a priority for ministry or unable to respond to the Gospel, which

in turn causes the church itself to be deviancy-imaged by society as being self-serving.

The church can do a great deal to remove the stigma of deviancy imaging by simply seeking out people with disabilities

and bringing them into the church. People are often stereotyped when they are not known. The presence of people

with disabilities in the church would dispel stereotypes and the deviancy imaging would be destroyed by personal ex-

perience. Church members would then work to correct their own symbolic stigmatizing and also work to correct those

perceptions that they run across in the community.

Wound 7: Being multiply jeopardized/scapegoated

Because of my bodily/intellectual impairment and/or functional limitation, I am thought to be the

reason for many negative things that occur in the environments I find myself in. In the early 1900s

“feeblemindedness” was thought to be the cause of crime, degeneracy and disease in America, which

led to mandatory sterilization laws. In our society, people with disabilities are also often scapegoated

as the reason for divorce.

When a person with a disability arrives at a church, the response should be to ask, “What is the value added by the in-

clusion of this person in our congregation?” “What is God doing by bringing this person to us?” Typically, when a

person with autism (for example) comes, our response is, “Now what are we supposed to do with this person?” Instead,

our response should be, “What can we gain by this person being in our fellowship that we would not gain if they were

not here, and how can we contribute to the life of this person God has brought to us?”

Wound 8: Distanciation: usually via segregation and also congregation

Because of my bodily/intellectual impairment and/or functional limitation, I am distanced from the

rest of society via physical or social segregation. One only needs to make an attempt to get involved

with people living in group homes to experience the degree they have been distanciated from the rest

of society. Minimally, one must get fingerprinted even to develop a friendship with such people.

On the other hand, because of my bodily/intellectual impairment and/or functional limitation I am always

grouped with people who have disabilities because we are easier to manage that way. The overwhelming

presentation of difference in a large, congregated group is itself a contributor to people being segregated.

People should only be segregated for really good reasons—e.g., because they are a danger to themselves or others. How-

ever, when a person with a disability arrives at a church, often our initial response is to develop a separate group for

people like him or her. There can be reasons for such groups. However, if the only involvement in church by persons

with disabilities is in the context of a separate group, we are contributing to the wounding of that person. Integration

of persons with disabilities into the typical life of the church will indeed cause the typical life of the church to change;

however, it is the right thing to do and that change moves the church in the right direction.

Wound 9: Absence or loss of natural, freely given relationships and substitution with artificial/

bought ones

Wolfen s berg er's 18 Wound s of D isabi l ity, by J e ff and K athi McNa i r

3

Because of my bodily/intellectual impairment and/or functional limitation my life is filled with people

who are paid to be with me, whether they be social workers, group home staff or day/vocational pro-

gram workers. Research indicates that the average individual living in a group home is visited by some-

one not paid to be with him only once every 20-30 months. Here again, this can be at least partially

attributed to the manner in which human service agencies provide their services. There are many al-

ternative ways in which services could be provided that would increase the likelihood of the develop-

ment of freely given relationships.

The church offers great potential for the development of many freely given relationships with persons with disabilities.

These can occur at the church itself; however, they should also occur in the community. Community relationships can

revolve around going to ball games or bowling or just a periodic visit to the group home. Churches also typically offer

myriad opportunities for participation in social activities. To have a friend call and ask you to do something with him

is something that far too many people with disabilities have not experienced.

Wound 10: Loss of control, perhaps even loss of autonomy and freedom

Because of my bodily/intellectual impairment and/or functional limitation, I am placed in settings that,

although they are described as being for my benefit, are largely designed on the basis of administrative

convenience. So, for example, adults living in a group home all go to bed at the same time, take showers

on the same evening and watch the same program on the television. Simple things such as taking a walk

in the community are often not possible because of the way in which staffing arrangements are made.

Additionally, those who would attempt to offer freedom are stifled because of the changes that these

freedoms cause in the lives of persons with disabilities. This includes aspects of religious freedom.

Autonomy and freedom are important aspects of life that the church can contribute to the lives of people with disabil-

ities. They are provided the opportunity to eat too much, to talk too much, to walk around and just to experience life

with less regulation. The first step in this is for the church to advocate for religious freedom in the lives of persons with

various disabilities who might not experience such freedom because of the constraints their care providers place upon

them in not allowing them to attend church.

Wound 11: Discontinuity with the physical environment and objects, (“physical discontinuation”)

Because of my bodily/intellectual impairment and/or functional limitation, I may not have access to

the physical environment in ways that those without impairments do. These restrictions are blamed

on my disability; however, they are more often due once again to issues of administrative convenience.

The church can provide people with disabilities with access to valued things in the environment, such as a personal

Bible, a crucifix that one wears or displays on a wall and materials about upcoming programs. During worship serv-

ices, people with disabilities may have access to participation in communion, with all that that entails in a given

context. These types of access validate the person as being like everyone else, thereby giving them value.

Wound 12: Social and relational discontinuity, even abandonment

Because of my bodily/intellectual impairment and/or functional limitation, I may be abandoned

by my family or by the larger society. Research indicates that nonreligious families are significantly

Wolfen s berg er's 18 Wound s of D isabi l ity, by J e ff and K athi McNa i r

4

more likely to view the care of their family member as being the responsibility of the state and

not their personal responsibility. Thus, people with disabilities end up having relationships only

with people who are paid to be with them. At the same time, research also indicates that religious

parents of children with disabilities feel supported by their personal faith, but not by their cor-

porate faith (the church), which indicates that parents also experience relationship discontinuity

and distanciation.

The church offers great potential for participation in ongoing relationships and prevention of abandonment. When a

person with a disability comes, he is greeted and welcomed and his name is called. Perhaps he has a nickname that

causes laughter in those around him. People bring him a cup of coffee the way he likes it. These things may seem small,

but they are proof of a relationship, proof of inclusion in the group.

Wound 13: Deindividualization, “mortification,” reducing humanness

Because of my bodily/intellectual impairment and/or functional limitation, I am viewed as less than

fully human, because of my degree of dependence upon others, my functional limitations and the

“drain” I am on society, among other things. Abortion is disdained by most in the Christian world,

but even among Christians, exceptions may be made for disability. Because people with disabilities

are not perceived as being fully human, they experience some of the deindividualization that has been

described above. There are those in society who would ask the question, “What does it matter that

someone who is not fully a person has no freely-given relationships or limited freedom or has his life

restricted and managed?”

The church puts teeth in its pro-life position when people with all types of disabilities are present in the church. Even

apart from a relationship with such people, they are recognized as valued simply by their presence. As church members

develop relationships, they find that people with disabilities are people just like them. Growing up with people with

Down syndrome around cannot help but take the fear of Down syndrome from you. It can’t help but cause you to

second guess the recommendations of physicians pushing for prenatal diagnosis and abortion. The church also needs

to be active in speaking out against the deindividualization of people with disabilities in whatever form it is seen. This

advocacy begins with the actual presence of people with disabilities in the church.

Wound 14: Involuntary material poverty, material/financial exploitation

Because of my bodily/intellectual impairment and/or functional limitation, I can expect people to strip

me of what I have and prevent me from acquiring things. After all, what does it imply if I am a “ward

of the state” and I own a TV or stereo or nice clothes? The state is required only to maintain a subsis-

tence level of existence for me. This is “cold charity.” If I am victimized by staff that steal my posses-

sions—well, that is just too bad because staff are hard to find. The question might be asked whether I

would miss the stolen things anyway.

Although I myself may be poor, because I am a member of a church, I have access to the resources of the church. These

resources evidence themselves in a variety of ways. Research indicates that churches provide money, food, clothing

and education, among many other things. The church therefore has tremendous potential to minimize the wound of

poverty. Additionally, presence in the lives of people with disabilities can assist in the prevention of financial exploita-

tion. An extra set of eyes can work wonders.

Wolfen s berg er's 18 Wound s of D isabi l ity, by J e ff and K athi McNa i r

5

Wound 15: Impoverishment of experience, especially that of the typical valued world

Because of my bodily/intellectual impairment and/or functional limitation, I may never have been to

a restaurant or a ball game or a movie. If I do participate in these things, they are “special” events, not

typical events. Because care providers are held to minimal standards, group home outings can literally

be a once-a-month trip to the grocery store to get milk.

The kinds of typical experiences most people have can be provided via participation in churches. These include dinners

out, social outings, service projects and so on. Typically, people will be involved in nonreligious service projects and

assist only if they are asked. No wonder the range of experiences of those who participate in a church versus those who

don’t are significantly different!

Wound 16: Exclusion from knowledge and participation in higher-order value systems (e.g., religion)

that give meaning and direction to life and provide community

Because of my bodily/intellectual impairment and/or characteristic functional limitations, I am excluded

from religious groups. As a result of my lack of participation in such groups, I may lack moral guidance, am

not privy to the solace and comfort faith in God might bring and as a result am excluded from participation

in community and in society, as religious groups are the vehicle that many use to receive these benefits.

Through church participation, I learn that God loves me as I am, that I am not a mistake and that those who tell me

that I am a mistake are wrong. I learn about Jesus— who he is, what he did and what that means to me. I learn about

how to live. I learn about how God uses people like me to accomplish his purposes. I learn that if people are unkind to

me, particularly in a church situation, that I am not wrong—they are wrong for rejecting me. I come to a place where

I learn what it is to be loved and accepted by God through the love and acceptance I receive from those in the church.

Wound 17: Having one’s life “wasted”; mindsets contributing to life-wasting

Because of my bodily/intellectual impairment and/or functional limitation, my life is wasted by those

who are my care takers. I spend useless hours in day care or “vocational” settings, often due to the lack

of imagination of my care providers. That these settings exist as they do provides insight into the minds

of those who develop such programs, in terms of how they perceive people with disabilities.

When I come to church, I first learn that my life has value. I then learn that I have the potential to be of service to the

church. Churches need to be wise in how they assign the “low hanging fruit” of service. People who have the ability to

work with the children should be working with the children, not ushering. But for those to whom ushering is a challenge,

challenge them with ushering or greeting or handing out programs. I may spend my week in adult day care, but on

Sunday, I am an usher. I may make no money at all in my workshop all week, but on Sunday, I police the grounds

to be sure that the grounds are looking beautiful. Other opportunities might also be imagined such that people see

themselves as having responsibility that gives their life meaning.

Wound 18: Being the object of brutalization, killing thoughts and death making

Because of my bodily/intellectual impairment and/or functional limitation, society is increasingly seek-

ing to end the “burden” of my life. Abortions occur to prevent “suffering” of those with congenital dis-

Wolfen s berg er's 18 Wound s of D isabi l ity, by J e ff and K athi McNa i r

6

abilities, when in reality most of any suffering may be largely due to the way in which people are treated

by society rather than from the disability itself. Authors write about how the future may lead to the

limitation of health care access by those with disabilities.

As stated, the church can do tremendous good to reverse the trend toward eliminating persons with disabilities through

abortion and other means by having such people present in numbers that minimally reflect their numbers in the com-

munity. The church also holds responsibility to speak up in defense of the lives of persons with disabilities and to teach

regularly from the pulpit about the value of all life and the Christian’s responsibility in affirming that value. Unfortu-

nately, leadership is typically silent on these issues.

NOTES

1. Wolfensberger, W. (2000). “A Brief Overview of Social Role Valorization.” Mental Retardation, 38(2), 105-123.

2. Wolfensberger, W. (1972). Normalization: The Principle of Normalization in Human Services. Toronto: National Institute on Mental Retardation.

Wolfen s berg er's 18 Wound s of D isabi l ity, by J e ff and K athi McNa i r

7

Jeff and Kathi McNair are career special educators, and professors of special education.

They have been involved in ministry to adults with intellectual disabilities for over 30

years. Kathi’s area of expertise is students with learning disabilities. Jeff is the Director of the

Public Policy Center for Joni and Friends, and also directs the Disability Studies Program at

California Baptist University, one of the few graduate programs in disability ministry. He also

directs the university’s program in severe disabilities.

1

On Identification:

Same Lake, Different Boat

By Stephanie O. Hubach

Identify: to associate or affiliate oneself closely with a person or group.

T H E A M E R I C A N H E R I T A G E D I C T I O N A R Y

Bearing down on the pedals intently, I strained to maneuver my bike up one of the steepest hills in

town, weaving back to the safety of our house. The weather was hot, hot, hot— one of those incredibly

scorching summer days when the heat radiates off the pavement in waves, making the task of cycling

all the more arduous. Anyone watching from the outside would have observed that I was simply at-

tempting to ride a bicycle. But truth be known, on the inside I was running. Running away. Having

just moved to a small, rural Pennsylvania town from the fast-paced environment of a defense consulting

job in Washington, D.C., I had been trying to find a constructive way to fill my time until I found new

employment. After working sixty-hour weeks while completing my master’s degree, I was attempting

to slow down a bit and lead a more balanced life that included more time with my husband and other

people, and less time with data and spreadsheets.

On this particular day, I had decided to visit a local personal care home. In Pennsylvania, personal

care homes provide housing for individuals who do not need intensive nursing care, but cannot live

unassisted for any number of reasons. This means that they often house people with a variety of special

needs, including those with cognitive disabilities,

1

mental illness,

2

or physical disabilities. However, I

didn’t know any of that. I just thought there would be a few neatly dressed and mentally alert elderly

people who were sitting around watching TV, but were secretly waiting for the chance to engage in a

stimulating conversation or a rousing game of checkers with mes.

I was shocked at what I saw…and what I smelled…and what I heard. Upon opening the front door,

I was greeted by a long, dark, dingy hallway, and the smell of soiled diapers, and the sounds of human

woe. Although sensing that perhaps I had underestimated what I was getting myself into, I still cheer-

fully marched into the administrator’s office and offered to visit with anyone who was available. After

looking at me somewhat curiously, the woman directed me down the hallway to a room with a vaulted

ceiling where I was seated with a man named Paul, whose wife had recently died. The staff thought

perhaps my visit could help cheer him up. I had no idea what to say to him. He dutifully answered my

questions as we sat in the center of this room surrounded by people with various disabilities slumped

in their recliners, in wheelchairs, and on couches. I couldn’t wait to leave. After fifteen minutes, I had

tortured poor Paul long enough with my persistent questioning. Hoping to slip out without anyone

noticing, I was clearly distressed by my surroundings. The whole world seemed different when I stepped

outside. Trying to shake off how deeply disturbed I felt, I began pedaling home. I had attempted to

identify with people outside my comfort zone and determined it wasn’t for me.

Fast forward three and a half years later to a very frosty January when the weather was cold, cold,

cold. Subconsciously, I thought this delivery would be just like those depicted in the baby magazines,

full of glowing anticipation, where everyone is wearing white and everyone is happy. Instead, I found

myself in the hospital with my newborn son for his third admission in three weeks. Everything was in-

deed white, but everyone was not happy. This time, congestive heart failure had landed us in the nearest

children’s hospital about an hour from our home. That morning, Timmy had been diagnosed with a

very serious heart condition not uncommonly found in babies with Down syndrome. According to his

cardiologist, Timmy’s case was a “worst-case scenario” for this particular cardiac anomaly. The hole in

his heart was extremely large, about half the size of his little life-sustaining pump.

Still reeling from the news, we tried to settle into our assigned room that we were to share with

three other families for the next five days. Once again, I was shocked at what I saw…and what I smelled…

and what I heard. “Beep. Beep. Beep.” Amidst the constant blipping of monitors was the incessant cry-

ing of babies, not simply because they were hungry, but because they were often being probed with

needles. Usually, a nurse was trying to put in an intravenous line or draw blood for the afternoon lab

report. The nine-month-old baby across the room had lived in there for much of her short life. A little

girl who wandered down the hallway was literally missing half of her face. The sterile smells of hospital

bedding replaced that gentle Ivory Snow scent I longed for at home. But this time, I couldn’t walk out

the door and hop on my bike and ride back to the safety of our house. This was my world now. The

identification I had once ridden away from by choice was now mine by Providence.

Comfort and Identification

Most people are not immediately at ease with those who have disabilities—especially cognitive disabil-

ities or mental illness. While today’s generation of children has had greater exposure to individuals af-

fected by disability, most adults still struggle with a fear factor when first learning to relate to people

with disabilities. At times the fear is based on a stereotype that must be overcome. Sometimes it stems

from the awkward feeling that arrives when we just don’t know what to do or say. At times, we are con-

fronted with the honest truth that we wrongly look at disability as an abnormal part of life in a normal

world. In other instances, the discomfort comes from the vulnerable realization that disability is a con-

dition that any of us can (and many of us will) personally encounter at some point in our lifetime—

and that uncomfortable thought makes us want to run away.

There is also a societal component in that we live in a fragmented culture—one that is full of distinct

lobbying groups. Typically, these groups communicate at each other but not with each other. To the

degree that we passively absorb current postmodern cultural constructs about the impossibility of

communication across different groups of people, we will fail even to attempt to connect with others

whom we perceive to be different from ourselves. When we do this, we implicitly accept society’s view

of “community”—which is not a group of people bonded by intentionality but a group of people defined

On I d entif i cati o n: Sa m e Lak e , Diffe ren t Boat , by S t epha n ie H u b ach

2

entirely by their exclusivity. For example, notice how language has changed in the last generation. We

no longer refer to the “melting pot of America” to represent the cohesive bonding of this nation. In-

stead, “community” is a word used to define separate and distinct power groups. Listen carefully. You

hear it on the news every day: the Hispanic Community, the Black Community, the Muslim Commu-

nity, the Disability Community. When we focus on our differences, we tend to impart value—usually

negative—to those differences. Instead of connecting with people affected by disability by choosing to

stress our common humanity, we emphasize the differences to legitimize our desire to simply pursue

our own agendas—those specific to our “community”—whatever they may be.

There is a common expression: We’re all in the same boat. One doesn’t have to experience much of

life to recognize that this is an oversimplification of reality. A more accurate statement would be same

lake, different boat. It reflects the truth that, as human beings, we share a common story, but the details

of our experiences and our life circumstances may vary significantly. We are essentially the same but ex-

perientially different. However, the current societal emphasis goes far beyond this. Instead of seeing our-

selves in the same lake, but in different boats, we tend to see ourselves in different lakes entirely. The result

is that we end up feeling justified in simply seeking our own level of personal comfort in life—unaffected

by the needs or desires of those around us.

Let’s be honest. We all like comfort. One could even say that twenty-first century Americans are ob-

sessed with it. Our cars, our furniture, our clothes, our computer keyboards—even our coffee cups are

designed for ease of use. Just the right feel—a perfect fit. That’s comfort in the material sense. Now,

suppose someone says to you, “I just love my friends. I really identify with them.” What are they likely

referring to? It is highly probable that they are referring to a collection of people with whom their com-

fort level is high. To an outsider, it is a group where the commonality might be obvious across the indi-

viduals—consistent with society’s version of community. But The American Heritage Dictionary definition

of what it means to identify with another is much broader than this. It reads: “To associate or affiliate

oneself closely with a person or group.” This definition does not necessarily imply comfort or identifi-

cation that is easy—just identification that is purposeful.

Biblical Identification

The Bible is replete with rich teaching about and examples of genuine identification. From Genesis to

Revelation, the Scriptures demonstrate God’s intentional identification with us. Ponder the depth of

the word Emmanuel, which means “God with us.” From creation to the consummation of all things, God

is committed to intentional identification with the creatures he designed in his image. According to

Gerard Van Groningen, an Old Testament seminary professor, God’s divine covenants constitute a

“God-established, -maintained, and -implemented life-love bond.”

3

God’s covenants with his people

throughout the ages are exemplary of the Emmanuel principle.

Consider the covenant of creation, which is God’s implicit covenant with mankind made in the

context of the design of humanity. The bond of life and love is deeply rooted in God’s creation of man

as his image-bearer. It is the relationship between God and man, not just in the simplistic sense that

we usually think of the word relationship, but in the deeper sense of man’s essence—his bearing of the

divine image within himself—that binds man to God. Van Groningen continues, “This relationship is

an essential aspect of God’s covenant. The foundational idea of covenant is bond. God bound himself

to mankind as he bound mankind to himself. It was a bond of life and love.”

4

Not only are we created for loving service to God in his kingdom, but we bear the image of the King

himself within ourselves. Now, that’s identification! If God, who, in all his splendor and transcendence

Same Lake, Different B o at, b y Ste p hani e Huba c h

3

can choose to be imminent to us, shouldn’t we, who are clearly not transcendent, strive for association

with our fellow human beings?

How do we know this is possible for us? We can be confident of our calling to identification because

Jesus himself demonstrated it throughout his life. One of my favorite examples is in John’s gospel ac-

count of Jesus’ healing of the man who was born blind.

As he went along, he saw a man blind from birth. His disciples asked him, “Rabbi, who sinned,

this man or his parents, that he was born blind?” “Neither this man nor his parents sinned,”

said Jesus, “but this happened so that the work of God might be displayed in his life.” (John

9:1-3)

The disciples emphasize a sense of otherness in the way they refer to “this man” and in the way they

ask, “Who sinned?” Notice, however, that Jesus turns their question on its head and responds with a

statement reflecting God’s purposeful identification with the man’s life: “This happened so that the

work of God might be displayed in his life” (John 9:3). Jesus then proceeds to heal the man, but Jesus

does not disengage from the man born blind at that point even though the man goes on his own way.

The continuing account relays a subsequent squabble among the Pharisees, the man, and his family.

Under a barrage of questioning, the healed man repeatedly recounts his miraculous encounter with

the Christ, but the man is increasingly berated by those who do not want to accept it. Finally, the con-

flict ends with the Pharisees shouting at him, “You were steeped in sin at birth; how dare you lecture

us!” (John 9:34). And they throw him out.

However, the best part of the story comes in the next verse. It reads, “Jesus heard that they had

thrown him out, and when he found him…” (John 9:35). I love those words: “when he found him.” Jesus

went looking for the man. He was interested in more than just his disability. He was invested in him as

a person. Jesus then moves the relationship to another level and introduces himself as the Son of Man—

bringing the relationship full circle, back to a connection with God himself—the one who identified

with the man born blind even in his creation, when the image of God was stamped within. That’s pow-

erful!

Biblical Application

So, from the profound reality of God’s identification with us in our image-bearing and from Jesus’

practical example, how do we make the jump to our own application? What motivates us to connect

with others intentionally as God requires of us? Romans 12 gives a clue:

For by the grace given me I say to every one of you: Do not think of yourself more highly than

you ought, but rather think of yourself with sober judgment, in accordance with the measure

of faith God has given you. Just as each of us has one body with many members, and these

members do not all have the same function, so in Christ we who are many form one body,

and each member belongs to all the others. We have different gifts, according to the grace

given us. (Rom. 12:3-6a)

The first thing that motivates us to identify with others is a proper perspective on ourselves. “Do

not think of yourself more highly than you ought” (Rom. 12:3). We must recognize that we all have

needs—that is a normal part of life in an abnormal world. Our brokenness and neediness as humans is

On I d entif i cati o n: Sa m e Lak e , Diffe ren t Boat , by S t epha n ie H u b ach

4

universal; how it manifests itself is variable. It is same lake, different boat. Connecting to others in a con-

descending way is not an option. Intentionally associating with others because we can truly identify

with their human condition is essential.

Second, we will be motivated to identify with others when we realize that we rely on each other.

“Just as each of us has one body with many members, and these members do not all have the same

function, so in Christ we who are many form one body, and each member belongs to all the others”

(Rom. 12:4-5). There is an interdependent unity that comes from diversity in the body of Christ. Every-

one benefits when we choose intentional relationships with people of differing abilities. Notice that

the model for mutual reliance in Christ’s church is more intimate than same lake, different boat. It is same

body, different parts.

Third, we need to celebrate the giftedness of those with whom we connect. “We have different gifts,

according to the grace given us” (Rom. 12:6a). Because we are reliant on each other to bring complete-

ness to the body of Christ, everyone’s contribution is a gift in its own right. Note that our differing

abilities are seen as positive and purposeful. There is genuine joy in celebrating the unique qualities

that express God-given individuality in the context of unity.

Finally, “the grace given us” (Rom. 12:6a) is the ultimate basis for true person-to-person identifica-

tion. In the covenant family, grace is the glue that binds us to each other—regardless of nationality,

ability, gender, age, or any other defining characteristic. Those who have experienced God’s grace first-

hand know that our need for grace is universal. It is what allows us to relate to others, inside and outside

of the body of Christ, with humility and compassion. Of course, identification can be costly and some-

times a little uncomfortable on our part, but grace was exceedingly costly and excruciatingly painful

on God’s part. Remember: Emmanuel—God with us. Doesn’t that say it all?

Summary

When our son Freddy entered second grade, we were preparing to start Timmy in kindergarten at the

same elementary school. Knowing that Timmy occasionally pulled embarrassing stunts in public, I

was concerned that Freddy might feel self-conscious about sitting with Timmy on the school bus. So,

one day I asked Freddy how he felt about the prospect of riding on the bus together. Looking at me in

stunned amazement that I had even approached him with the question, Freddy replied indignantly, “I

would be proud to sit with my brother.”

How about you? Would you be proud to identify with your “brother” or “sister” who is disabled?

Then follow Jesus’ example—be intentional and go find them.

Personal Application Questions

1. How do you usually think about the concept of “identification”? Do you typically con-

sider identification to be related to comfort, commonality, or intentionality?

2. What fears do you have about relating to people who have disabilities?

3. How does God’s example of identification with us help you to overcome those fears?

4. What does it mean to say “same lake, different boat—we are all essentially the same but

experientially different”?

5. Whom will you choose to identify with today?

Reprinted from Same Lake, Different Boat: Coming Alongside People Touched by Disability by Stephanie O. Hubach, copyright 2006, P & R Publishing,

Phillipsburg, NJ.

On I d entif i cati o n: Sa m e Lak e , Diffe ren t Boat , by S t epha n ie H u b ach

5

NOTES

1. “‘Cognitive disabilities’ is often used by physicians, neurologists, psychologists and other professionals to include adults sustaining head injuries

with brain trauma after age 18, adults with infectious diseases or affected by toxic substances leading to organic brain syndromes and cognitive

deficits after age 18, and with older adults with Alzheimer diseases or other forms of dementia as well as other populations that do not meet the

strict definition of mental retardation.” Thus, cognitive disabilities is an “umbrella” term that includes intellectual disabilities (formerly referred to as

mental retardation) but is broader than intellectual disabilities alone. (Source: U.S. Administration on Developmental Disabilities)

2. “A mental illness is a disease that causes mild to severe disturbances in thought and/or behavior, resulting in an inability to cope with life’s ordinary

demands and routines. There are more than two hundred classified forms of mental illness. Some of the more common disorders are depression,

bipolar disorder, dementia, schizophrenia, and anxiety disorders.” (Source: National Mental Health Association)

3. Gerard Van Groningen, Messianic Revelation in the Old Testament, vol. I (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 1997), p. 59-60.

4. Ibid., 103.

On I d entif i cati o n: Sa m e Lak e , Diffe ren t Boat , by S t epha n ie H u b ach

6

Stephanie Hubach serves as Mission to North America’s Special Needs Ministries Director. Mission to

North America is an agency of the Presbyterian Church in America. She also currently serves on the

Lancaster Christian Council on Disability and the Faith Community Leadership Advisory Board. Steph is

the author of Same Lake, Different Boat: Coming Alongside People Touched by Disability and All Things Possible: Call-

ing Your Church Leadership to Disability Ministry. She has been published in byFaith magazine, Focus on the

Family magazine, and Breakpoint online magazine. Steph and her husband Fred have been married for

27 years. They have two deeply loved sons: Fred and Tim, the younger of whom has Down syndrome.

1

A True Friend Identifies

By Joni Eareckson Tada

Have you ever watched a football game and seen those crazy fans in the stands wearing face paint

and funny hats, braving temperatures well below zero? They scream at the top of their lungs to cheer

for their team, as if the players will actually listen to their instructions. And put them in front of a

TV camera and you would think they had just won the lottery! If you are watching the game at home,

you say to yourself, “Why do they do that?”

The answer isn’t found in the win-loss record of the team. In baseball, for example, some of the

most avid fans are Cub fans—and the Cubs haven’t won the pennant in eighty years! The answer lies

not in the team itself but in the heart of the true fan.

What the crazy fans in the stadium, as well as the more subdued fans in the living room (like

my husband, Ken, and I!), experience in our heart is called identification. We identify with the team.

Our identity as individuals is tied, even in a small way, to the team. As a resident of the Los Angeles

area, the Lakers are a part of me and I feel like a part of them. If they win, we’re happy. If they lose,

we’re sad. (Ken more than me!) And we will defend the honor of the team to any who would dis-

parage it.

A true fan will recount stories of past triumphs. Or quote statistics on the players. Or wear jackets,

hats, pins, and shirts with the team’s logo—even during the off-season. A true fan will do this because

he or she identifies with the team. Wouldn’t it be wonderful if we identified with one another as peo-

ple in the same way? Someone’s hurt becomes my hurt? Someone’s hope becomes my hope?

Nowhere is a sense of identification more needed than in relationships between nondisabled peo-

ple and disabled people. Whether you simply cross each other’s paths briefly or become intimate

friends, developing a sense of identification with a disabled person is the most important and re-

warding step you can take. To identify with a person with a disability will mean that you have taken

yet another step in conforming to the image of Christ.

If identification is that important, let’s define it and then describe it in further detail. Webster’s

dictionary says it is a “process by which a person ascribes to himself the qualities or characteristics

of another person.” It is also described as “the perception of another person as an extension of one-

self” (that is, your pain is my pain; your joy, my joy).

Nobel Prize winner Herbert Simon describes identification this way: “We will say that a person

identifies himself with a group when, in making a decision, he evaluates the several alternatives of

choice in terms of their consequences for the specified group (or person).”

The essence of a friendship with a person with a disability is that we think about choices (how we

will act, what we will say) based upon their impact on that person and consider that person to be an ex-

tension of ourselves. It means that we will look at the world from their perspective and act accordingly.

Whether or not we identify with someone with a disability will depend upon these two factors: what

we know about a person and how well we value that person. Borrowing again from Herbert Simon,

these factors are called “premises.” We make decisions about things and about people based on premises

of what we believe to be true (facts) as well as the things that are important to us or that we care about

(values).

To illustrate how we make decisions, imagine for a moment that you’re in the market for a car. Your

pragmatic nature determines that safety and economy might be important values to you. As you shop

for cars, you will base your decision on information related to those values. Miles per gallon, air bags

and antilock brakes will all be key factors in helping you determine which car you buy. (If you choose

a convertible sports car, you weren’t being honest about what you valued. Looks and speed were prob-

ably more important to you!)

When it comes to our attitudes toward other people, we go through a similar process. Because an

attitude is simply a decision we make with regard to a person, idea, or thing, our values and the infor-

mation available to us will be of central interest.

Let us take this line of thinking and illustrate how you can not only describe your attitude toward

a person with a disability, but also how you can grow in your relationship with that person or group

of people. At the same time, we will see other attitudes that are prevalent in our society today regarding

people with disabilities.

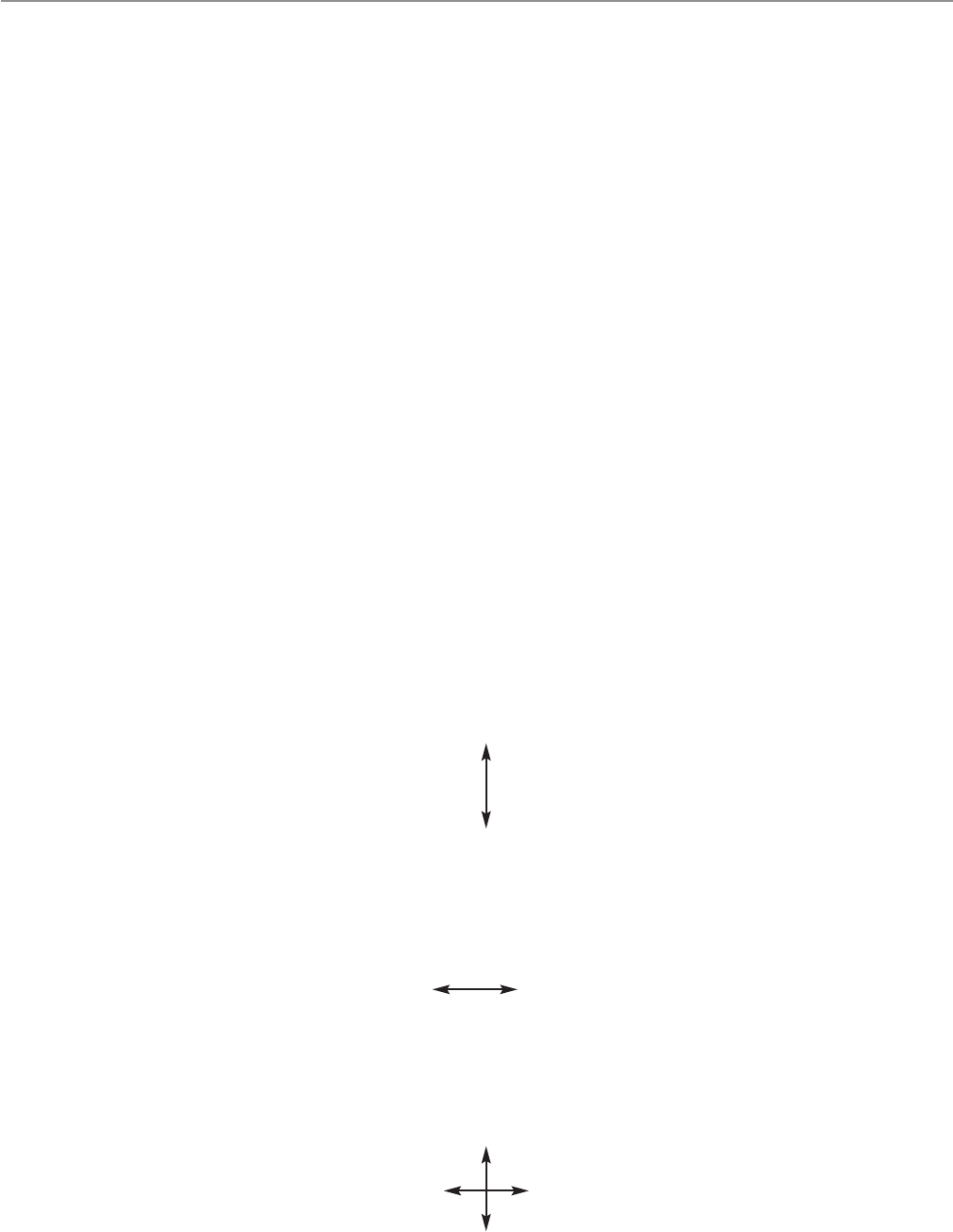

First, think about information regarding people with disabilities. You can have varying amounts

of accurate or inaccurate information (facts) about someone. Represented in graphic form, it looks

like this:

A Tr u e Fri e nd I d e ntif i es, b y Jon i Earecks o n Tada

2

+ Facts

- Facts

+ Facts

- Facts

Second, think about your value regarding people with disabilities. Your value can move in a positive

or negative direction and can be represented this way.

Those of you who remember (enjoyed or dreaded!) algebra class can see where I’m going with this.

Put the two lines together to form a graph of Facts and Value:

- Value + Value

- Value + Value

You will notice that when we formed this graph, we created four areas or quadrants. Look at each

quadrant to see what’s there.

Quadrant 1: Lesser value with little or inaccurate information.

This is the quadrant of Indifference. “I don’t know and I don’t care” is how someone with little value

and little or inaccurate information would express it. Very few would actually say it that way, but it is

prevalent in our society when it comes to working with disabled people. As a group, disabled people

have experienced discrimination and have had to work hard to get the most essential laws passed to

protect them from indifference.

Quadrant 2: Lesser value but with accurate and increasing amount of information.

This is the quadrant of Insensitivity. A person may know what is happening with people with disabilities

but may not respond positively because he or she doesn’t care or has become burned out from caring.

This often happens with those working professionally in the field of disability. The disabled person

may become just another “problem,” “case” or “file.”

Quadrant 3: Positive value but with inaccurate or inadequate information.

This is the quadrant of Ignorance. A lot of people in churches fall into this category. They care a lot—

Christ’s example and command prompt this—but they simply don’t know much about people with dis-

abilities. They are unaware. That is why much of disability ministry is geared toward building awareness.

Ignorance can be expressed in things such as assuming a person who is mentally disabled is also deaf.

Or a person in a wheelchair might be assumed to be mentally disabled. You can imagine how people

would interact in such cases and why friendships or acquaintances would be so hard to get started.

A Tr u e Fri e nd I d e ntif i es, b y Jon i Earecks o n Tada

3

- False

Indifference

- Value

+ Facts

Insensitivity

- Value

1

2

- Facts

Ignorance

+ Value

3

Qu

a

d

ra

n

t

4

:

P

o

s

itive

v

a

lu

e

w

ith

m

o

r

e

,

a

c

c

u

ra

te

in

f

o

r

m

a

tio

n

.

T

his

is

t

he

qua

d

r

a

nt

of

I

d

e

nt

if

ic

a

t

ion.

T

he

m

or

e

we

va

lue

a

p

e

r

s

on

wit

h

a

d

is

a

bilit

y

a

nd

t

he

m

or

e

we

kno

w

,

t

he

m

or

e

w

e

will

id

e

nt

if

y

wit

h

t

he

m

.

N

ot

ic

e

t

ha

t

wit

h

e

ve

n

a

lit

t

le

bit

of

inf

or

m

a

t

ion

a

nd

a

lit

t

le

bit

of

va

lue

,

you ha

ve

m

ove

d

awa

y f

r

om

whe

r

e

m

a

n

y p

e

op

le

a

r

e

in s

oc

ie

t

y

.

As

w

e

m

o

v

e

fu

r

t

h

e

r

i

n

t

o

t

h

e

q

u

ad

ran

t

o

f

Id

e

n

t

i

fi

c

at

i

o

n

,

w

e

l

e

arn

m

o

re

ab

o

u

t

a

p

e

rso

n

.

An