Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 95 (2024) 128309

Available online 22 March 2024

1618-8667/© 2024 Elsevier GmbH. All rights reserved.

Effect of biophilic shopping environments featuring Christmas trees on

perceived attentional and mental fatigue: A national study

Chad D. Pierskalla

a

,

*

,

1

, Jinyang Deng

a

, David W. McGill

a

, Shan Jiang

b

a

West Virginia University, School of Natural Resources, 1145 Evansdale Drive, Morgantown, WV 26506, USA

b

Director of Research, GBBN Architects, 5411 Penn Ave, Pittsburgh, PA 15206, USA

ARTICLE INFO

Handling Editor: Dr Cecil Konijnendijk van den

Bosch

Keywords:

Attention Restoration Theory

Biophilic design

Christmas trees

Mental health

Soft fascination

ABSTRACT

The Mayo Clinic and the American Psychiatric Association recognize that many people experience stress around

the holidays. For example, households with children, people living alone, etc. during the Christmas holiday

might be feeling mentally fatigued or maybe they simply want to improve their mental state. We aimed to

investigate the extent to which Christmas tree shopping environments that include real trees in the outdoors (a

common type of biophilic store design) provide opportunities to help them recover from mental and attentional

fatigue (derived from Attention Restoration Theory) when compared to articial indoor tree displays. A

nationwide online survey (n=1208, 45 questions, and two video evaluations) was used to compare real-time and

post video evaluations of outdoor displays of real Christmas trees with indoor displays of articial Christmas

trees using two measures of overall perceived restorative quality. The key nding indicates that real/outdoor

trees have a higher perceived restorative quality (real-time video evaluation p <.05 and post-video evaluation p

<.001). Although the fascination ratings for articial/indoor tree ratings were signicantly higher (p <.01), it

had a much weaker effect than real trees (less than half) on overall restorative quality. That is, although indoor

articial trees were more fascinating, it appears to be the kind of “hard” fascination that does not contribute

nearly as much to restoration when compared to the “softer” fascination associated with real trees. The positive

effect of coherence (e.g., orderly tree displays) and scope (e.g., perception of depth and spaciousness) on overall

restorative quality that was perceived by respondents was greater for real/outdoor tree displays. These larger

effects were measured in a multivariate multiple regression model but also identied in most of the peak

restorative moments during the video evaluation.

1. Introduction

The Mayo Clinic (and other top-ranked hospitals and health orga-

nizations) recognize that many people experience stress around Christ-

mas. For example, the American Psychiatric Association reported that

41% of people in their study experienced stress and anxiety during the

holiday season (American Psychiatric Association, 2021). Based on the

literature that documents the mental health benets of nature immer-

sion (e.g., immersion in nature in general, in biophilic shopping stores,

and during urban forest bathing), it seems possible that shopping for real

Christmas trees can help answer Mayo Clinic’s call for restoring the

inner calm (Mayo Clinic, 2020). The purpose of the nationwide study is

to examine and compare the extent to which Christmas tree shopping

environments that include real trees in the outdoors (i.e., choose and cut

farm, garden center, and home improvement store) and articial trees

indoors (i.e., variety of chain store displays) provide opportunities for

the recovery from mental fatigue and have the capacity to focus atten-

tion. By doing so, this research will ll a void in the literature by

examining not only the factors of attention restoration associated with

different Christmas tree shopping environments (outdoor biophilic de-

signs offering real trees vs. indoor store designs offering articial trees),

but it will also identify the specic natural elements that contribute to

positive consumer responses.

Despite the plethora of literature that identies the health benets of

nature, the authors are not aware of any research that empirically ex-

amines the phenomena in detail as it relates to the Christmas tree

shopping environment (a common biophilic store design in our com-

munities that can offer forest bathing opportunities during the holidays).

* Corresponding author.

E-mail address: [email protected] (C.D. Pierskalla).

1

304-216-4844

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ufug

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2024.128309

Received 12 October 2023; Received in revised form 13 February 2024; Accepted 21 March 2024

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 95 (2024) 128309

2

1.1. Immersion in nature in general

Nature and plants have been traditionally viewed as healers in the

history of human development (Jiang, 2022). Trees have been associ-

ated with many spiritual and therapeutic qualities in different cultures

due to their longevity, historical status, and continuity from one season

to another (Squire, 2002). Landscape architects started to associate

nature and parks with human salutogenesis as early as in the 18th

centenary – several urban park systems were initiated by Frederick Law

Olmsted (known as the father of American landscape architecture and

arguably also park management given it was a topic once taught in

landscape architecture schools) to address the stress, pollutions, and

unhealthy living conditions in major American cities (Szczygiel and

Hewit, 2000). The visual qualities of natural environment have been

proven with dominant effects in reducing people’s stress (Ulrich et al.,

1991) and relieve mental fatigue (Kaplan, 1995). The amount or density

of trees in outdoor spaces usually serves as a positive predictor of peo-

ple’s aesthetic preferences and high degrees of restorativeness (Wang

et al., 2019). Increasing tree coverage can also provide health benets

associated with cooling urban environments (Lungman et al., 2023).

Tree coverage (more so than low-lying vegetation or grass) was associ-

ated with a decreased risk of postpartum depression (Sun et al., 2023). In

intimate spaces, the psychological benets of plants include

stress-reduction, emotional support, and increased pain tolerance

(Bringslimark et al., 2009). The multi-sensory stimuli, particularly the

odorant stimuli from nature, such as methyl salicylate (wintergreen

scent), have been universally rated as smelling healthful (Dalton, 1999).

1.2. Immersion in biophilic store designs

The growth of urbanization and the hectic pace of life are just a few

reasons why the health benets of green infrastructure, such as biophilic

designs, are important (Hung and Chang, 2022). Although Biophilic

Design (including store designs like outdoor Christmas tree lots) is a

relatively new line of research, the idea of bringing plants into houses

and gardens reects the biophilic quality of the human mind and is

common in most cultures including those that go back more than 2000

years (Grinde and Patil, 2009). Kellert et al. (2008) proposed the bio-

philic design of landscape architecture to describe methods that include

natural elements, patterns, natural lines etc. in the built environment.

Hung and Chang (2022) used the perceived biophilic design items

(PBDi) in their study to explain landscape preferences and positive

emotional states in urban green spaces. They conclude that “Vegetation,

waterscape, sky, etc., with the appropriate landscape layout, create a

kind of fascination, an important component that attracts involuntary

attention and inuences human perception and positive emotions.” (p.

9). More specically, the concept of biophilic store design was intro-

duced by Joye et al. (2010) as the integration of greenery or natural

elements into the built retail environment. Adding elements of nature

can help counteract shopper boredom stemming from a lack of newness

and unique experience in built environments like shopping malls

(Rosenbaum et al., 2018) that may suffer from what Verde and Wharton

(2015) call customer “discovery decit”.

1.3. Immersion in nature during forest bathing

Immersion in an urban forest during the practice of Shinrin-Yoku,

known as forest bathing, can lead to a plethora of positive health ben-

ets for human physiological and psychological systems (Hansen et al.,

2017). The idea of forest bathing originated in Japan in the 1980s. It

involves slow, mindful sensory activities (e.g., slow wandering) that can

occur in 10–15 minutes, typically in natural areas such as forests, parks,

and yards with plants (Kil, 2022). Song et al. (2016) demonstrated that a

15-minutre walk in an urban park can decrease stress and heart rates.

Sturm et al. (2022) found that weekly 15-minute outdoor walks (called

awe walks that offer awe-inspiring moments) for 8 weeks promoted

prosocial positive emotions in older adults. An example of an even

shorter recovery time was documented in an experimental study where

participants restored their attention directed at a task and lowered their

skin conductance level (SCL) after watching a 5-minute nature video,

which they called a nature break condition. On the higher end of re-

covery time, Berman et al. (2008) found that study participants realized

positive effects on short-term memory and directed attention when

exposed to nature during a 50-minute walk. Perhaps the better sugges-

tion for the minimum time dose of nature immersion (e.g., forest bath-

ing) was offered by Meredith et al. (2020). Their review of 14 studies,

published in Frontiers in Psychology, found that 10–50 minutes sitting or

walking in natural spaces helped improve mood, focus and physiological

markers (e.g., blood pressure and heart rate), but the benets tended to

plateau after 50 minutes. Ten of the 14 studies they examined were

conducted in Japan where the government has heavily promoted forest

bathing programs. Given the seemingly endless benets of forest bath-

ing, it is important to nd ways to create opportunities in more aspects

of our lives, especially during stressful periods of time or seasons of the

year.

1.4. Conceptual framework

Attention Restoration Theory (ART) is a specic theoretical frame-

work associated with the mental health benets of nature (Kaplan,

1995), and it was used in this study. A large body of research has

accumulated in support of ART and is one of the most important and

widely adopted theories that explains nature’s restorative effects (Lin

et al., 2014). Marketing research efforts that explore the restorative

potential (i.e., recovery of mental fatigue) of commercial environments

primarily draw from ART and are especially important for this study

(Kaplan, 1995; Kaplan, 2001; Berto, 2005; Joye et al., 2010). In addi-

tion, over 100 studies of recreation experiences in wilderness and urban

nature areas indicate that restoration is one of the most important

verbally expressed benet opportunities afforded by nature (Ulrich,

1981). ART suggests that prolonged mental effort leads to fatigue and

natural environments foster restoration because they hold non-taxing

attention (Kaplan, 1995). That is, natural environments allow infor-

mation processing mechanisms to recover from the mental fatigue that

results from everyday life and hassles. Prolonged and excessive demands

commonly require focused attention and considerable effort (Kaplan,

1995). Mental fatigue can lead to a variety of problems such as psy-

chological stress, and since attention is essential for human effective-

ness, there can be a decline in problem solving, decline in behaving

appropriately, increase in irritability, increase in accidents, etc. (Berto,

2007). As emphasized by Kaplan (1995, p. 172), “the restoration of

effectiveness is at the mercy of directed (focused) attention fatigue.” A

way to benet from attention regeneration (Berto, 2005) and recover

from stress (Ulrich, 1981), is by exposure to natural environments.

2. Method

2.1. Conceptual and operational denitions of ART concepts

The Perceived Restorativeness Scale (PRS) was developed to measure

the extent to which environments have restorative qualities (Hartig

et al., 1997). PRS is based on ART and was initially made up of

twenty-six items that measured study respondent’s perception of the

restorative factors (including those presented by Kaplan,1995) that can

exist in an environment to varying degrees. The scale has been

frequently reported in the literature, and in 2014, a short form of the

scale was developed to make it more suitable for research where time is

limited (Pasini et al., 2014). Based primarily on this work (Kaplan, 1995;

Hartig et al., 1997; Pasini et al., 2014), the conceptual and operational

denitions of ve restorative factors (fascination, being-away, compat-

ibility, coherence, and scope) associated with PRS follow.

C.D. Pierskalla et al.

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 95 (2024) 128309

3

2.1.1. Fascination

The fascination of settings can hold one’s attention effortlessly and

without capacity limitations. Natural settings such as clouds, sunsets,

snow patterns, leaves in the breeze are examples because they are un-

dramatic (e.g., gentle form of fascination called soft fascination) and

allow the perceiver to think about other things as well (Kaplan, 1995).

This is one of the main components of a restorative environment and was

measured using items including ‘Places like this are fascinating’, ‘In

places like this, my attention is drawn to many interesting things’, and

‘In places like this, it is hard to be bored’.

2.1.2. Being-away

This concept involves physicacl and/or psychological being-away

from demands on directed attention. Being-away is a setting that is

physically or conceptually distant from everyday environments, un-

wanted distractions, reminders of one’s usual work, noise, and stimu-

lation overload. A sense of being away is important but it does not

require that the setting be distant. It was measured with items including

‘Places like this are a refuge from nuisances’ and ‘To stop thinking about

the things that I must get done, I like to go to places like this’.

2.1.3. Coherence

ART originally focused on four restorative factors including fasci-

nation, being-away, compatibility, and extent. Extent was dened as

being in a whole different world that entails large tracts of land or in a

small area that seems much larger with the addition of trails, paths, etc.

that are sufcient to sustain exploration. Extent involves a place “rich

enough and coherent enough so that it constitutes a whole other world”

(Kaplan, 1995, p. 173). Therefore, extent was later thought to comprise

elements such as coherence and scope. Coherence is an orderly envi-

ronment with distinct areas, and repeated themes and textures. “In a

coherent environment, things follow each other in a relatively sensible,

predictable, and orderly way” (Kaplan, 2001, p. 488). The items used in

this study include ‘There is a clear order in the physical arrangement of

places like this’, ‘In places like this it is easy to see how things are

organized’, and ‘In places like this everything seems to have its proper

place’.

2.1.4. Scope

Scope is the second element of extent. It requires a setting that is

physically or conceptually large enough so that one’s mind can wonder,

and their thoughts can drift away from daily activities (Lin et al., 2014).

The items measured include ‘That place is large enough to allow

exploration in many directions’ and ‘In places like that there are few

boundaries to limit my possibility for moving about’.

2.1.5. Compatibility

Compatibility or the match between a person’s goals and inclinations

and the demands provided by the environment can also be important.

Analogs of compatibility include Csikszentmihalyi’s (1975) “ow”

experience which is an optimal experience that involves becoming

immersed or feeling “in the zone”. It can occur when the degree of

challenge is balanced with one’s skillfulness (physical or mental). The

items include ‘Being in places like this suits my personality’, ‘I can do

things I like in places like this’, and ‘I have a sense that I belong in places

like this’.

2.2. Development of videos and study instrument

Literature using visual representations of environmental conditions

has traditionally been found in studies of environmental aesthetics and

restorative character. For example, methodologies including photo-

graph, simulation and video, and self-reported experiences (closed and

open-ended survey/journal) have been used. The goal of these methods

is to produce the most valid and reliable data on measuring environ-

mental preference (Brown and Daniel, 1987). Historically, most

research has been conducted posteriori with a researcher providing

students with a series of photographs or slides and asking participants to

evaluate these images on a preference scale (Ewing et al., 2005). A re-

view of three texts containing 58 research studies on aesthetics or

restorative character of the natural environment utilized 60 different

methodologies: 73% used photographs/slides, 17% experiential, 8%

used computer simulation/virtual reality, and 2% used video (Kaplan

and Kaplan, 1989; Nasar, 1992; Sheppard and Harshaw, 2001). Most

studies were posteriori (conducted off site after photos, simulations, or

videos were taken). Only two studies were conducted on site, asking

participants to visit the area of study and assess conditions. However,

Qin et al. (2008) also used real-time evaluations of videos (2 minutes in

length) to study the visual quality of a scenic highway. Pierskalla et al.

(2016) used real-time evaluations of videos (4–6-minutes in length) to

examine the scenic beauty along ve streets in the historic district of

Savannah, GA. Therefore, the study presented in this paper further lls

the void in the literature by examining videos with a length that falls

within that narrow range of 2–6 minutes.

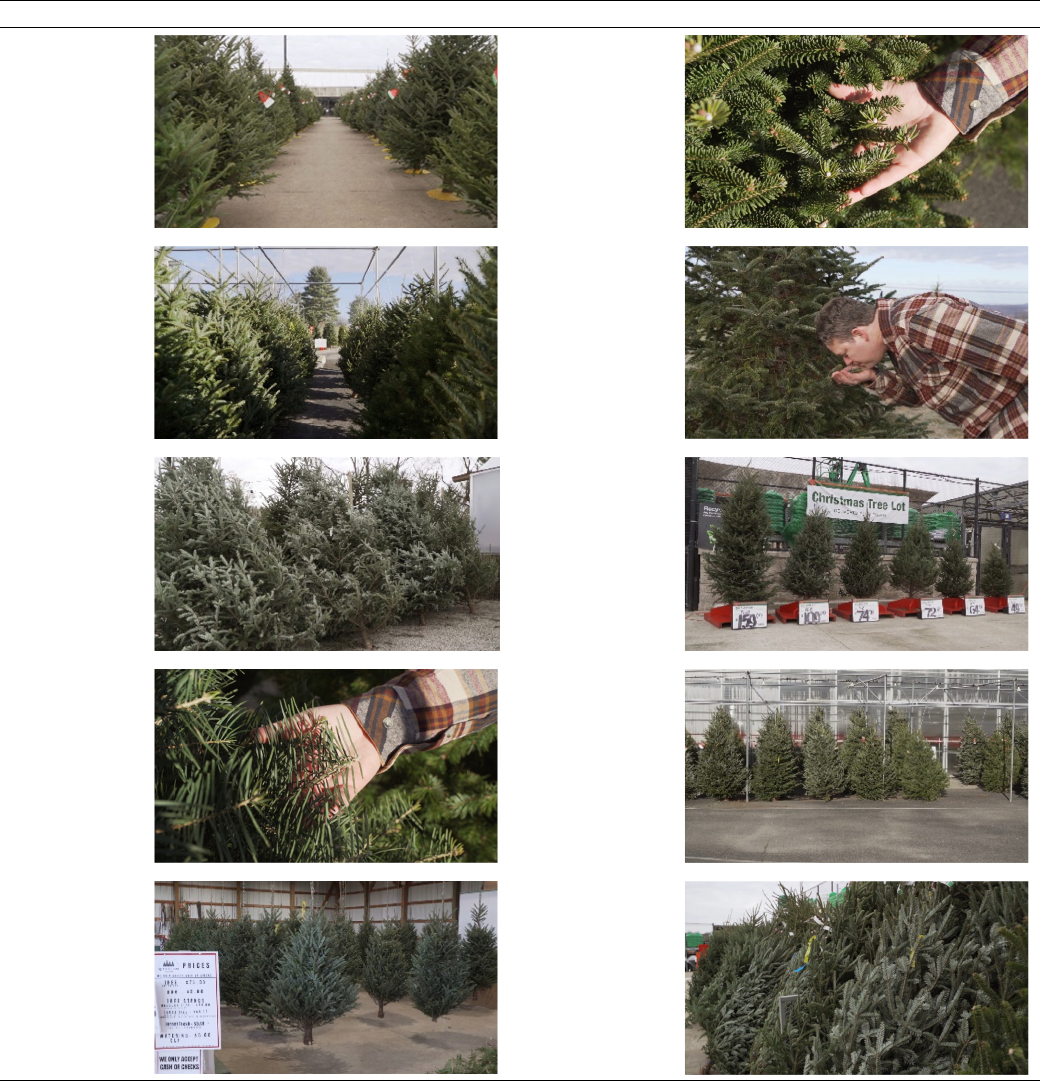

Two videos (three minutes in length) were created that represent two

categories of Christmas tree shopping environments: (1) real trees dis-

played in the outdoors (i.e., choose and cut farm, garden centers, Boy

Scout lot, and home improvement store) and (2) articial trees displayed

indoors (i.e., variety of chain store displays). (See Tables 9 and 10 for

photos representing both videos). We wrote and used the same video

script for each Christmas tree business including main entrance, land-

scape view or broad overview of full tree displays using 180-degree

rotating view on a tripod, walk along tree displays of various heights,

and close view of tree needles (short and long) in the researcher’s hand.

Following the script, the videos were produced by a professional vide-

ographer during the rst week of December 2022 with each business

represented in random order within the video. Given this is a quasi-

experimental design, the researchers were not able to control every-

thing presented in the video which is a study limitation.

Continuous audience response technology (CART) provided by

Dialsmith LLC was used to collect moment-to-moment and post-video

evaluation responses from respondents. The perception analyzer sys-

tem technology has been used to conduct focus groups and market

research, and to measure audience reaction to video such as advertise-

ments, lms, and campaign messages “so everything that is perceived is

also recorded…Nothing slips through the cracks." (Dialsmith, 2023). In

this study, there newest technology, the on-screen slider for online video

evaluations, was used within an online survey instrument.

Our online survey started by asking respondents to read a denition

of “restorative qualities”:

We would like you to evaluate the “restorative qualities” of Christ-

mas tree shopping environments or settings that you perceive in a three-

minute video. Before you start the short video evaluation, take a

moment to better understand what we mean by “restorative qualities” of

a Christmas tree shopping environment by carefully reading the

following: When you experience environments or settings with the

highest “restorative qualities” you are more likely to:

i. recover from mental fatigue

ii. improve your ability to concentrate

iii. restore your capacity to focus your attention

iv. feel less irritable in these settings as you recover from mental and

attentional fatigue.

On the other hand, when you experience environments or settings

with the lowest “restorative qualities” you are less likely to recover from

mental and attentional fatigue.

Following a twenty second practice video clip, respondents were

asked to evaluate one of the two randomly selected videos based on a

100-point ‘restorative quality’ scale by using the on-screen slider. Note

that this 100-point scale is a single-item or global measure of attention

restoration (dependent variable) that was used because it would not be

C.D. Pierskalla et al.

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 95 (2024) 128309

4

practical to ask respondents to evaluate multiple restorative factors

(independent variables including fascination, being-away, coherence,

scope, and compatibility) simultaneously during every second of the

video evaluation. The evaluation began with the on-screen slider set at

the midpoint (50). Respondents were asked to move the slider to the

right (100 = highest quality) if they felt that the restorative quality has

improved in the setting and to the left (0 = lowest quality) if it

decreased. Data were collected during every second of the three-minute

video evaluation. Post-video evaluations were also included to assess the

ve restorative factors of the Christmas tree shopping environment

based primarily on previous work (Kaplan, 1995; Hartig et al., 1997;

Pasini et al., 2014). A total of thirteen PRS items (representing ve

restorative factors including fascination, being-away, coherence, scope,

and compatibility) were evaluated on 0–10-point scale, where 0 = not at

all to 10 = completely. The specic items that were examined were

dened earlier in this paper. In addition, respondents were asked to

provide a post-video assessment (0 = not at all to 10 = completely) of

their overall perception of “restorative quality” represented in the type

of environments or settings shown in the video. Questions regarding

socio-demographics were also included in the survey such as gender,

race, age, education, household income, type of household, and region

of country of residence.

2.3. Sampling

Sampling was conducted by Dialsmith, Inc. during the last week of

January 2023. Dialsmith uses the Cint platform which offers 4,500+

panel partners and 28,259,312 panelists in the USA. Study participants

were contacted through online recruitment, email recruitment, specic

invitations, and loyalty websites. All participants/panelists are subject

to comprehensive quality checks. Dialsmith, Inc. distributed the online

survey using the sample provider. Study participants included both

current and potential customers of real Christmas trees. Upon successful

completion of a survey, the panelists were immediately credited with a

$4.50 (or a $4.50 points equivalent) incentive.

2.4. Data analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 28. Descriptive

statistics for response rate, socio-demographics, region, type of recent

Christmas tree purchase, etc. are provided. Chi-square was used to

examine the association of type of Christmas tree purchase and house-

hold. Several t-tests examined differences of the ve restorative factors

(measured with PRS scales) by type of video evaluated (real/outdoor vs

articial/indoor trees). ANCOVA was used to examine the effect of a

video on overall restorative quality (both real-time and post-video

evaluations) while controlling for the ve restorative factors. Multi-

variate multiple regression (MMR) was used to measure the effect of the

ve restorative factors on both measures of overall restorative quality.

Moment-to-moment results (e.g., timelines) helped pinpoint the peak

restorative quality identied in the real/outdoor and articial/indoor

trees videos.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Sample characteristics

A nationwide sample of 1208 qualied completed surveys (604 re-

spondents per video) were collected. The response rate was 57% and the

average completion time was fourteen minutes and nineteen seconds

(median = 10:24). The sample was also balanced across four regions of

the US (South = 30.6%, Northeast = 22.1%, Midwest = 21.3%, and West

= 26.0%). It was also reasonably balanced among several demographics

including gender (51.3% females), race (18% Black or African Ameri-

cans, 61.3% White/Caucasian, 16.1% Hispanic or Latino, and 10.6%

Asian), age (15–30% per age category from 18 to 24–55–64 years old),

education (ranging from 18% high school graduate or equivalent to 16%

graduate degree), and household income (12.6% with less than

$20,000–22.7% with $100,000+).

Nearly one third of the respondents had a real Christmas tree in their

home in 2022 and 50.7% only had an articial Christmas tree (Table 1).

The remaining respondents (16.6%) did not have any Christmas tree in

their home. Table 2 further breaks down these frequencies by type of

household. Households most likely to have a real Christmas tree in their

home include a foster child (100%), roomer/boarder (100%), child

(44.4%), opposite-sex spouse (42.4%), other nonrelative (54.5%),

grandchild (40.0%), and same-sex spouse (38.1%). That is, the top

market for real Christmas trees includes households with children.

On the other hand, those living alone were least likely (34.4%) to

have any tree and could potentially benet from the restorative expe-

rience associated with shopping for a real tree outdoors (Table 1).

Loneliness and isolation are considered an epidemic in the United States

with serious health risks (Ofce of the Surgeon General, 2023).

Although loneliness and isolation are widespread throughout the pop-

ulation, Nguyen et al. (2020) identied a signicant association between

loneliness and not having a spouse or partner (p<.001) across all age

groups examined in their large nationwide survey. Given the high per-

centage of respondents living alone without a home Christmas tree, easy

access to forest bathing opportunities in local lots and farms could be

especially useful to them. Cuncic (2021), medically reviewed by Morin,

provided several ways to cope with being alone at Christmas including

addressing their mental state. The restorative benets offered when

shopping for a real tree might be another way to accomplish that.

Of those respondents that indicated they had a real Christmas tree in

their home, most purchased their tree at a chain store (37.2%), followed

by a retail lot (29.2%), choose and cut farm (27.3%), nursery (23.0%),

online (19.2%), and non-prot group (12.2%) (Table 3). This reects a

balanced sample among shopping locations.

3.2. Fascination of articial/indoor trees

The Perceived Restorative Scales (PRS) are reliable and have Cron-

bach’s alpha scores near or well above 0.70. The items were measured

on an 11-point scale (0 = Not At All to 10 = Completely). Fascination

and its items (Table 4) were the only ratings that were signicantly

different (t-test, 2-sided p <.01) between participants (n = 604) who

evaluated the video representing real/outdoor Christmas trees and

participants (n = 604) who evaluated the video representing articial/

indoor Christmas trees. Specically, the fascination mean scores were

higher (Cohen’s d = 2.5–3.1) for the group evaluating the articial/in-

door tree video. As explained later, this type of fascination might not be

the “soft” fascination that is required for a restorative experience given

the much smaller effect (Partial

ɳ

2

=.024) on overall restorative quality

perceived in the articial/indoor trees video.

3.3. Perceived restorative quality of real/outdoor Christmas tree displays

When the authors used analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) to test for

differences in overall restorative quality represented in the videos, the

results were signicant (p <.05). ANCOVA is a general linear model that

combines ANOVA and regression to examine random treatment effects

(real/outdoor trees vs. articial/indoor trees video evaluations) on

overall perceived restorative quality. Covariates (i.e., fascination, being-

Table 1

Type of Christmas tree(s) in your home in 2022.

Type of tree n Percent

Only a real Christmas tree(s) 247 20.4

Only an articial Christmas tree(s) 613 50.7

Both articial and a real Christmas tree(s) 148 12.3

No Christmas tree (real or articial) 200 16.6

C.D. Pierskalla et al.

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 95 (2024) 128309

5

away, compatibility, coherence, and scope) were included in the general

linear models to help increase precision of the treatment effect. By

controlling for those ve restorative factors using ANCOVA, both mea-

sures of perceived restorative quality were signicantly (p <.05) higher

for the real/outdoor Christmas trees video (Tables 5 and 6). That is, the

authors reject the null hypothesis that our treatment (randomly assigned

video) results in equal mean restorative quality: real-time video evalu-

ation F(1, 1201) = 4.126, p =.042 (Table 5) and post-video evaluation F

(1, 1201) = 15.96, p <.001 (Table 6). The effect size of the video (partial

ɳ

2

=.013) on overall perceived restorative quality was greater for the

post-video evaluation measure (Table 6). Although the effect size is

acceptable (Cohen, 1969), it was greatly increased (partial

ɳ

2

=.057) by

narrowing the inclusion criteria of the analysis to those respondents that

did not have a real or articial tree in their home in 2022 (Table 7).

Arguably these respondents have less bias from a personal preference for

purchasing real or articial trees that could impact evaluations. These

ndings suggest that future research that uses an even more robust

method is very promising.

3.4. The effect of restorative factors on perceived restorative quality

Multivariate multiple regression (MMR) analysis was used to better

understand the effect that the ve restorative factors (predictors) have

on two measures of overall perceived restorative quality (1. post-video

assessment and 2. real-time video assessment) for each video

(Table 8). The overall test for multiple responses (two dependent vari-

ables) was used in this study because it is more powerful than separate

univariate regressions (one dependent variable) and it avoids multi-

plying error rates. Also, since separate univariate regression analysis of

both dependent variables provided similar results, only the MMR results

are provided in Table 8.

The assumptions for MMR that were examined in this study were

satised. Both dependent variables are related conceptually and are at

least moderately correlated (r =.583) which is ideal. Scatterplots indi-

cate that the relationships between the dependent and independent

variables are positive and linear. The predicted values that were plotted

against standardized residuals (i.e., residual plot) were symmetrically

distributed (clustering towards the middle of the plot) and did not have

any clear patterns which is also ideal.

The effects (partial

ɳ

2

) of the ve restorative factors (predictors) on

the overall perceived restorative quality can be compared for both

videos in Table 8. Most notable is the larger effect fascination, coherence

and scope have on overall restorative quality perceived in the real/

outdoor trees video. Compatibility was the only factor to have a notably

larger effect size for the articial/indoor trees video. The discussion of

these results follows.

Fascination had about twice the effect on perceived restorative

quality for real/outdoor trees when compared to articial/indoor trees

(Table 8). This means that although articial/indoor trees were

considered more fascinating by study participants as shown in Table 4, it

is the kind of fascination that does not make a major contribution to the

overall perceived restorative quality. Articial Christmas trees located

inside stores (see Table 10 which shows the top restorative moments of

the video), with all the lights displayed, are very fascinating, but it is

more likely a "hard" fascination. Hard fascination includes factors like

fast movements and loud noises including watching sports games on

television or visiting amusement parks. Perhaps the sometimes ashing

(i.e., fast movements), bright and high value, and even clashing or

chaotic colors of lights common in indoor Christmas tree displays are

also a type of hard fascination. On the other hand, “soft” fascination

involves stimuli that does not require much effort (which reduces the

internal noise and burden). Classic examples include wind blowing

through leaves or ripples of water traveling across a pond. Based on our

study’s ndings, shopping for real Christmas trees outdoors may provide

another example of “soft fascination” – a type of fascination that has a

larger effect on restorative quality. This nding helps address the calls to

better understand fascination (Basu et al., 2018) which argue that soft

fascination is key but an underexamined element of Attention Restora-

tion Theory. These results also have broader consequences for future

research that examines the restorative quality of fast moving and

sometimes chaotic light stimuli such as cell phones and video games.

Scope had a much larger (partial

ɳ

2

=.046) and signicant (p <.001)

effect on perceived restorative quality of real/outdoor Christmas trees

when compared to articial/indoor trees (partial

ɳ

2

=.007, p =.141)

(Table 8). Outdoor retailers have an advantage over indoor stores

because they offer a setting (or the impression of a setting) that is

physically or conceptually large enough so that one’s mind can wonder

Table 2

Household by type of Christmas tree(s) in home in 2022 by household.

Type of Tree in the Home

1

Household

(Check all that

apply)

Real Tree Articial

Tree Only

No Tree

χ

2

df Cramer’s

V

Opposite-sex

Spouse

(Husband/

Wife)

206

(42.4%)

244

(50.2%)

36

(7.4%)

64.50* 2 .231*

Opposite-sex

Unmarried

Partner

30

(27.5%)

63

(57.8%)

16

(14.7%)

2.41 2 .045

Same-sex

Spouse

(Husband/

Wife)

8

(38.1%)

10

(47.6%)

3

(14.3%)

0.30 2 .016

Same-sex

Unmarried

Partner

3

(23.1%)

7 (53.8%) 3

(23.1%)

0.73 2 .025

Child 192

(44.4%)

212

(49.1%)

28

(6.5%)

69.97* 2 .241*

Grandchild 2

(40.0%)

2 (40.0%) 1

(20.0%)

0.23 2 .014

Parent

(Mother/

Father)

67

(27.8%)

130

(53.9%)

44

(18.3%)

3.34 2 .053

Brother/Sister 54

(33.3%)

87

(53.7%)

21

(13.0%)

1.81 2 .039

Other relative

(Aunt,

Cousin,

Nephew,

Mother-in-

law, etc.)

17

(32.7%)

30

(57.7%)

5

(9.6%)

2.10 2 .042

Foster Child 3

(100.0%)

0 (0%) 0 (0%) 6.19 2 .072

Housemate/

Roommate

16

(32.0%)

25

(50.0%)

9

(18.0%)

0.08 2 .008

Roomer/

Boarder

2

(100.0%)

0 (0%) 0 (0%) 4.12 2 .058

Other

nonrelative

6

(54.5%)

4 (36.4%) 1

(9.1%)

2.45 2 .045

No one (I live

alone)

46

(22.0%)

91

(43.5%)

72

(34.4%)

60.29* 2 .223*

*Signicant (p <.001)

1Percentages are by rows.

Table 3

Purchase location of your home’s real Christmas tree(s) in 2022.

Type of Business (check all that apply) n Percent

Real tree from a chain store (Walmart, Home Depot, Lowes, etc.) 147 37.2

Real tree from a choose and cut farm 108 27.3

Real tree from a retail lot 115 29.1

Real tree from a nursery 91 23.0

Real tree from a non-prot group (Boy Scouts, churches, etc.) 48 12.2

Real tree purchased online 76 19.2

Other location 8 2.0

I don’t know 4 1.0

C.D. Pierskalla et al.

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 95 (2024) 128309

6

and their thoughts can drift away from daily activities (i.e., scope). It is

not surprising that scope is an important restorative factor. Research

suggests that park-like stands of trees with increased visual access and

depth are appealing landscapes to people. In addition, distant views that

are opened-up, especially to the horizon, are highly preferred landscapes

(Heerwagen and Orians, 1993). We propose that scope (depth percep-

tion) in tree displays, especially for small outdoor displays where space

is a premium, can be enhanced by modifying the (1) textural density, (2)

relative size, (3) occluding events, and (4) linear perspective of the

trees—each are explained in detail below.

(1) Gibson’s ecological perception theory suggests that the rate of

change in a landscape’s textural density provides cues for depth

perception (Bruce and Green, 1990). For example, a customer

who views a display of trees (having uniform tree size and density

throughout the display) will naturally notice an apparently lower

density of trees in the near setting and higher density of trees in

Table 4

Perceived Restorative Scale (PRS) item mean scores by real/outdoor trees video versus articial/indoor trees video.

Real/Outdoor Tree

Video

Articial/ Indoor Tree

Video

Perceived Restorativeness Scale (PRS) items

a

M SD M SD t(1206) p (2-sided) Cohen’s d

Fascination 5.80 2.54 6.35 2.49 -3.76 <.001 2.51

Places like this are fascinating 5.83 2.94 6.28 2.87 -2.72 .007 2.90

In places like this, my attention is drawn to many interesting things 6.23 2.71 6.96 2.55 -4.79 <.001 2.63

In places like this, it is hard to be bored 5.35 3.04 5.80 3.09 -2.58 .010 3.06

Scale reliability: Cronbach’s alpha .849 .847

Being-away 5.60 2.63 5.50 2.88 0.61 .541 2.75

Places like this are a refuge from nuisances 5.65 2.84 5.41 3.03 1.37 .171 2.94

To stop thinking about the things that I must get done, I like to go to places like this 5.55 3.13 5.59 3.33 -.205 .838 3.23

Scale reliability: Cronbach’s alpha .709 .773

Coherence 7.03 2.10 6.96 2.12 0.56 .577 2.11

There is a clear order in the physical arrangement of places like this 6.99 2.31 6.84 2.43 1.09 .275 2.37

In places like this, it is easy to see how things are organized 7.11 2.34 7.07 2.37 0.269 .788 2.35

In places like this, everything seems to have its proper place 6.99 2.34 6.97 2.34 .135 .892 2.34

Scale reliability: Cronbach’s alpha .885 .873

Compatibility 5.77 2.72 5.99 2.82 -1.36 .174 2.77

Being in places like this suits my personality 5.82 2.95 6.02 3.04 -1.18 .237 2.99

I can do things I like in places like this 5.84 2.86 6.05 2.90 -1.30 .194 2.88

I have a sense that I belong in places like this 5.66 2.99 5.89 3.10 -1.32 .187 3.05

Scale reliability: Cronbach’s alpha .918 .930

Scope 6.63 2.11 6.59 2.16 0.34 .731 2.13

That place is large enough to allow exploration in many directions 7.16 2.36 7.10 2.37 0.44 .662 2.37

In places like that, there are few boundaries to limit my possibility for moving about 6.10 2.58 6.08 2.62 0.17 .868 2.60

Scale reliability: Cronbach’s alpha .623 .658

Note: The abbreviations M and SD stand for mean and standard deviation respectively.

a

Perceived Restorativeness Scale (PRS) items measured on a 11-point scale (0 = Not At All to 10 = Completely).

Table 5

ANCOVA: Real-time video evaluations of overall perceived restorative quality

a

by video (controlling for ve restorative factors

b

)—including all study

respondents.

Effect of Video

Treatment Groups (videos) Mean SD F p Partial

ɳ

2

Real/outdoor trees video 61.79 21.37 4.126 .042 .003

Articial/indoor trees video 60.70 19.75

a

Dependent variable: Perceived restorative quality was measured every sec-

ond (in real time) during the video evaluation on a 100-point scale from

0=lowest quality to 100=highest quality.

b

Covariance: The ve restorative factor mean scores include Fascination,

Being-away, Coherence, Compatibility, and Scope.

Table 6

ANCOVA: Post-video evaluations of overall perceived restorative quality

a

by

video (controlling for ve restorative factors

b

)—including all study respondents.

Effect of Video

Treatment Groups (videos) Mean SD F p Partial

ɳ

2

Real/outdoor trees video 6.40 2.81 15.96 <.001 .013

Articial/indoor trees video 6.16 2.66

a

Dependent variable: Overall perceived restorative quality (post-video eval-

uation) was measured on a 11-point scale (0=Not at All to 10=Completely).

b

Covariance: The ve restorative factors include Fascination, Being-away,

Coherence, Compatibility, and Scope.

Table 7

ANCOVA: Post-video evaluations of overall perceived restorative quality

a

by

video (controlling for ve restorative factors

b

)—including only respondents

with no real or articial tree in their home during 2022.

Effect of Video

Treatment Groups (videos) Mean SD F p Partial

ɳ

2

Real/outdoor trees video 5.31 2.81 11.63 <.001 .057

Articial/indoor trees video 4.54 3.03

a

Dependent variable: Overall perceived restorative quality (post-video eval-

uation) was measured on a 11-point scale (0=Not at All to 10=Completely).

b

Covariance: The ve restorative factors include Fascination, Being-away,

Coherence, Compatibility, and Scope.

Table 8

Multivariate Multiple Regression (MMR): Effects of restorative factors

a

on

restorative quality

b

.

Real/Outdoor Christmas

Trees Video

Articial/Indoor Christmas

Trees Video

Restorative factors p Partial

ɳɳ

2

p Partial

ɳɳ

2

Fascination <.001 .052 <.001 .024

Being-away <.001 .045 <.001 .049

Coherence <.001 .057 <.001 .047

Compatibility <.001 .032 <.001 .096

Scope <.001 .046 .141 .007

a

Independent variables: The ve restorative factors were measured on 11-

point scales from 0=Not At All to 10=Completely.

b

Dependent variables: Perceived restorative quality was measured with two

variables: Real-time video evaluation measured on a 100-point scale from

0=lowest quality to 100=highest quality and post-video evaluation measured on

an 11-point scale from 0=Not at All to 10=Completely.

C.D. Pierskalla et al.

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 95 (2024) 128309

7

the distant setting. The trees nearest the customer will also

appear larger in scale than distant trees. These gradients of

texture are perceived invariants and inform the visitor about the

depth of the setting (i.e., provide scope). It is possible for retailers

to heighten the perception of depth by altering this gradient

pattern of trees. Establishing higher densities of smaller trees on

the outmost edge, while allowing lower densities of larger trees to

exist in the near setting by the entrance, can potentially heighten

impressions of a landscape surface receding away; thus we pro-

pose that it can enhance depth perception and make the space

appear larger. Exiting this same space would have the opposite

effect because the space would be compressed, and the customer

would feel immersed and pulled into the setting which could also

provide a unique and enjoyable experience.

(2) Similar to gradient pattern cues, we propose that relative size

cues can also be enhanced to give the impression of a receding

landscape of a space. The relative size of an object depends upon

its distance. When a retinal image is large it can either be a small

object up close or a large object that is far away. Therefore, when

perceiving two similar objects such as two trees, there can be a

tendency to see the smaller tree further away. Because the distant

or background trees (on the outmost edge) are smaller in absolute

size, the relative depth would be increased.

(3) A third type of cue that is used to perceive depth is occlusion.

Occlusion is a category of events wherein objects (e.g., smaller

background trees) occasionally disappear and reappear when

overlapping with other objects (e.g., larger foreground trees) or

as they become wiped away or hidden from our peripheral view

during human movement (Strickland and Scholl, 2015). Our vi-

sual systems make effective use of these monocular interpositions

(overlapping objects) to deduce the depth relations among ob-

jects (Kaplan, 1969). This impression can be magnied by tran-

sitioning from large to small trees, wherein a larger number of

background trees are hidden.

(4) Linear perspective is a fourth type of depth cue that can enhance

the impression of receding landscape scenery. The technique in-

volves using parallel lines (like railroad tracks) that converge in a

single vanishing point, and it is often used by artists and archi-

tects. In theatre, it is used to make small spaces appear larger. In

our Christmas tree display example, trees can be presented in

such a way (V-shaped or triangular pattern) as to create linear

perspective (convergence of landscape pattern near the horizon

or background) and enhance the perception of depth of an

otherwise small space.

Compatibility was a signicant predictor (p <.001) for the restor-

ative quality perceived during both videos, but it was notably larger

(about 3 times larger) for articial/indoor Christmas trees (Table 8).

Analogs of compatibility include Csikszentmihalyi’s (1975) “ow”

experience which is an optimal experience that involves becoming

immersed or feeling “in the zone”. It can occur when the degree of

challenge is balanced with one’s skillfulness (physical or mental). The

real Christmas tree industry should continue to nd ways to improve

services (e.g., tree delivery and set-up) that can reduce the challenge of

purchasing a real Christmas tree or increasing the perceived self-efcacy

of some prospective customers. For example, 27.6% of study re-

spondents of Kansas households listed allergies or health problems as a

reason for purchasing an articial tree (Hilderbrandt, 1991). Providing

allergy-friendly trees might help those customers perceive

compatibility.

3.5. Top ten restorative scenes of the real/outdoor Christmas trees video

Fig. 1 shows the evaluation timeline and the top ten scenes with peak

restorative quality that were perceived in the real trees video. Those

scene snapshots are provided in Tables 9. Some recommend that

landscape architects and service design researchers try to better un-

derstand the specic types of natural elements (e.g., certain types of

trees and plants, forms of water displays, or the presence of small animal

life such as birds and butteries) that evoke positive consumer responses

(Rosenbaum et al., 2018). This study helps address this call for addi-

tional research and offers propositions and recommendations about how

to improve the biophilic design of real Christmas tree farms and lots (e.

g., choose and cut farm, garden centers, Boy Scout lot, and home

Fig. 1. Evaluation timeline for the real/outdoor Christmas trees video.

C.D. Pierskalla et al.

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 95 (2024) 128309

8

improvement store).

Pictures 1, 3, 5, 6, and 9 are innovative tree displays that represent

coherence and scope in varying degrees (Table 9). These pictures further

support the importance of coherence (organized trees) and scope (a

receding landscape or depth) as contributing factors of restorative

quality and compliments the ndings presented in Table 8. They

represent a type of organized complexity (the right balance of order and

variety or contrast) that affords an ideal perception of depth and

spaciousness.

Pictures 2 and 10 represent large trees (Table 9). Although customers

tend to prefer purchasing smaller trees (6–8’), they perceive higher

restorative quality when larger trees were presented in the video (pic-

tures 2 and 10). The preference of large trees in studies of scenic beauty

is well established. For example, based on preference rating (5-point

scale) of 100 scenes, Herzog (1984) identied three dimensions or cat-

egories of scenes including one called, large trees, which received the

highest scores among the dimensions (3.79 on a 5-point scale). The

ratings increased to 4.0 when the trees were viewed in combination with

pathways which can offer a pleasing effect as a boarder element or

refuge. (Note: Similar to this study, Herzog, 1984, would sometimes

Table 9

Peak restorative moments identied during the evaluation of real/outdoor trees video.

Timeline Position Peak restorative video scenes Timeline Position Peak restorative video scenes

1

6

2 7

3 8

4 9

5 10

C.D. Pierskalla et al.

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 95 (2024) 128309

9

refer to the work of Kaplan and Gibson in his publications). Locating the

larger trees near the pathway entrance (foreground or front row) might

also enhance the impression of depth and scope of a place.

Picture 4 represents the positive effect of smell and pictures 7 and 8

represent the positive effect of tactual stimuli of both short and long

needle trees on restorative quality (Table 9). There is evidence to suggest

that biophilic store design can prot from these contributors of restor-

ative quality. For example, natural tree buyers ranked fragrance as a top

reason for their purchase and suggests that scents affect product and

store ratings, shopping times, and sales (Larson, 2004). Furthermore,

other researchers (Leenders et al., 1999) advise that at least 70 percent

of shoppers should be aware of the scent. In summary, all these rec-

ommendations support the importance of multi-sensory stimuli,

particularly the odorant stimuli from real trees in biophilic shopping

environments (Dalton, 1999).

Being able to categorize the peak restorative moments into cate-

gories based mostly on factors of ART provides face validity for this

study. The authors also tried to minimize the presence of people in the

video unless they were intentionally highlighting the non-visual stimuli

(i.e., smell and touch) of both environments captured in the video.

3.6. Top seven restorative scenes of the articial/indoor Christmas trees

video

The evaluation timeline and the top seven scenes with peak restor-

ative quality that were perceived in the articial trees video are pro-

vided in Fig. 2. Those scene snapshots are provided in Table 10. Despite

the diversity provided in the video (large to small displays with varying

sized trees), the articial tree evaluations have less variability, and the

timeline is atter when compared to real trees (e.g., the difference be-

tween scene 1 and 6 in Fig. 2 is 4.20 on a 100-point restorative scale). It

seems that shopping for articial trees is less eventful (i.e., affording

fewer awe-inspiring opportunities) when compared to shopping for real

trees.

4. Conclusion

This study helps ll several voids in the literature by examining

overall restorative quality (two dependent variables) and individual

factors of ART (ve independent variables) associated with different

Christmas tree shopping environments (outdoor biophilic designs of-

fering real trees vs. indoor stores offering articial trees). It also iden-

ties the specic natural elements that contribute to perceived

restorative quality.

The key nding indicates that real/outdoor tree store displays have a

higher perceived restorative quality (two dependent variables measured

as real-time and post-video evaluations) when compared to articial/

indoor trees, especially for those that are likely more neutral in their

preference of trees (i.e., did not have any real or articial tree in their

home). Therefore, this study provides the rst empirical evidence to

support public health recommendations to forest bathe in Christmas tree

displays at local choose and cut farms, garden centers, Boy Scout lots,

home improvement stores, or other type of outdoor tree lots, especially

for customers seeking recovery from mental fatigue. This can be the

beginning of a promising line of research if additional situational vari-

ables such as type of tree display are considered in future research. The

main study ndings also provide support for a recent CNN article’s

(Marples, 2021) proposition that real Christmas trees can provide

important health benets such as the reduction in anxiety, psychological

stress, and depression. The Mayo Clinic (2020) and American Psychi-

atric Association (2021) recognize that many people experience stress

around the holidays. For example, households with children and those

that are living alone during the Christmas holiday might be feeling

mentally fatigued or maybe they simply want to improve their mental

state. The outdoor biophilic designs that are common at retail tree farms

and lots can help those customers recover from mental fatigue, improve

Fig. 2. Evaluation timeline for the articial/indoor Christmas trees video.

C.D. Pierskalla et al.

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 95 (2024) 128309

10

their ability to concentrate, restore their capacity to focus their atten-

tion, and help them feel less irritable as they recover from mental and

attentional fatigue. In essence, real Christmas tree displays and farms

make a convenient forest bathing opportunity for people, even for those

that do not purchase a tree.

The examination of independent variables (i.e., ve factors of ART)

also led to important ndings. The potential lure of articial tree dis-

plays and their sometimes ashing (e.g., fast movements), bright and

high value, and even clashing colors of lights (Fig. 2) should be ques-

tioned by customers seeking attention restoration and the recovery from

mental fatigue, and it should be further examined in future research. The

ndings from this study suggest that this type of fascination might be

like other “hard” fascinations such as fast movements and loud noises

including watching sports games on television or visiting amusement

parks, and they do not contribute to overall restoration at a level similar

to real Christmas tree displays. Stimuli categorized as “hard” fascination

forcefully grab customers’ attention and are difcult to resist or let go. In

fact, there was very little variability (fewer awe-inspiring moments) in

the relatively at or uneventful evaluation timeline for articial indoor

trees. “As a result, they tend to ll the mind, leaving little room for more

Table 10

Peak restorative moments identied during the evaluation of articial/indoor trees video.

Timeline Position Peak restorative video scenes Timeline Position Peak restorative video scenes

1

6

2 7

3

4

5

C.D. Pierskalla et al.

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 95 (2024) 128309

11

peripheral mental activity or reection”’ (Basu et al., 2018, p. 1057).

Hard fascination “eventually leads to mental fatigue and symptoms such

as distractibility, impulsivity, and irritability” (Basu et al., 2018, p.

1056). On the other hand, the biophilic nature of outdoor tree displays

appear to offer the “soft” fascination that reduces the internal noise and

mental burden for customers much like the effect of wind blowing

through leaves or ripples of water traveling across a pond. It is this “soft”

fascination that contributes more to restoration because it captures

attention effortlessly. Our study’s nding is especially important and

interesting considering it can be connected to William James’ (1962)

discussion of attention (later referred to as fascination) that was pub-

lished over 130 years ago and more recently by Kaplan (1995) and

others.

The display of real Christmas trees may also have an advantage over

indoor displays of articial trees because they offer a setting that is

physically or conceptually large enough so that a customer’s mind can

wonder and their thoughts can drift away from daily activities (i.e.,

scope). That type of setting can also offer coherence when there are

orderly displays of trees with repeated themes and textures. In fact, most

of the peak restorative moments identied during the evaluation of real/

outdoor trees video involved innovative displays that had the charac-

teristics of scope and coherence. Based on these ndings, we provided

some propositions on how to further improve the perception of depth,

spaciousness, and the impression of a receding landscape, especially for

small spaces. We suggest that tree displays can be enhanced by modi-

fying the textural density, relative size, occluding events, and linear

perspectives of trees. These propositions seem promising and deserve

the attention of future research.

Other restorative design elements of real Christmas tree displays that

were identied in the video evaluation include the presence of larger (or

taller) trees. Based on the literature, these larger trees could be located

near a pathway as a boarder element to the customers’ experience (even

though they are not the most preferred size tree for purchase). And as we

also proposed, they could be located near the pathway entrance (fore-

ground or front row) to enhance the impression of depth and scope of a

place which can also improve the perceived restorative quality.

Compatibility was a signicant predictor of restorative quality for

both real/outdoor and articial/indoor trees, but the effect was about

three times larger for the latter. This issue can be addressed by nding

additional services that can reduce the challenge of purchasing a real

Christmas tree for some customers. Some current examples include tree

delivery and setup services.

The broader implications of this study can help designers of all types

of open-air biophilic store designs, not just Christmas tree shopping

environments. Marketing research on the restorative potential of com-

mercial environments (a contemporary retail phenomenon referred to as

‘biophilic store design’ by pioneering marketing researchers) is often

drawn from ART (Rosenbaum et al., 2018). S

¨

oderlund and Newman

(2015) summarize research that indicates shoppers and shop employees

were less stressed and there was increased retail potential when bio-

philic initiatives were used in a commercial context. More recently,

Rosenbaum et al. (2018) conducted three studies that used ART and PRS

to link biophilia design of lifestyle centers (a type of open-air retail

setting) to the restoration from mental fatigue. Based on their research,

they conclude that “when biophilic elements are incorporated into

lifestyle center design, shoppers can sense the restorative potential of

these centers. Resultantly, those who spend time in restorative lifestyle

centers may experience catharsis from negative symptoms associated

with mental burnout and fatigue” (Rosenbaum et al., 2018, p. 72).

Landscape architects and service design researchers are trying to better

understand the specic types of natural elements that evoke positive

consumer responses (Rosenbaum et al., 2018). Our study supports this

line of research by pinpointing aspects of popular biophilic store designs

that help people recover from mental fatigue during the holidays.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

David McGill: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acqui-

sition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Jinyang Deng:

Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Methodology,

Writing – review & editing. Shan Jiang: Conceptualization, Funding

acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Chad David

Pierskalla: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding

acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Re-

sources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing –

original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing nancial

interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to inuence

the work reported in this paper. Chad Pierskalla, Jinyang Deng, David

McGill, Shan Jiang

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support from the Real Christmas Tree Board

(RCTB). Project Number: 22–11-WVU. Special thanks to Beth Bossio

from The Quarter Pine Tree Farm for her assistance with the study.

Research in the News

https://www.womansworld.com/posts/home/when-to-decorate-fo

r-christmas

https://www.cbsnews.com/texas/video/shopping-for-christmas-t

rees-can-boost-your-mental-health/

https://www.cbsnews.com/chicago/video/study-nds-real-chr

istmas-trees-is-good-for-mental-health/

https://www.kfyrtv.com/video/2023/12/21/can-real-christmas-t

ree-benet-mental-health/

https://wvutoday.wvu.edu/stories/2023/07/20/a-reason-to-

celebrate-christmas-in-july-wvu-research-shows-real-christmas-trees-

boost-mental-health

https://www.lootpress.com/wvu-research-shows-real-christma

s-trees-boost-mental-health/

https://www.hampshirereview.com/living/article_bd7c5e90-36b

0-11ee-a186-7b7bf28c633c.html

https://www.newswise.com/articles/a-reason-to-celebrate-chr

istmas-in-july-wvu-research-shows-real-christmas-trees-boost-menta

l-health

https://ground.news/article/a-reason-to-celebrate-christmas-in-

july-wvu-research-shows-real-christmas-trees-boost-mental-health

https://www.wvnstv.com/science/christmas-in-july-new-study-sh

ows-real-christmas-trees-can-help-with-mental-fatigue/

https://www.mybuckhannon.com/a-reason-to-celebrate-christmas

-in-july-wvu-research-shows-real-christmas-trees-boost-mental-health/

https://www.wtrf.com/west-virginia/west-virginia-school-says-sh

opping-for-a-real-christmas-tree-is-good-for-you-mental-health/

https://www.connect-bridgeport.com/connect.cfm?func=view&i

tem=A-Reason-to-Celebrate-Christmas-in-July-Research-at-WVU-Sh

ows-Real-Christmas-Trees-Aid-Mental-Health52319

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2021). Holiday stress. https://www.psychiatry.org/

File%20Library/Unassigned/APA_Holiday-Stress_PPT-REPORT_November-2021_

update.pdf.

Basu, A., Duvall, J., Kaplan, R., 2018. Attention restoration theory: exploring the role of

soft fascination and mental bandwidth. Environ. Behav. 51 (9-10), 1055–1081.

Berman, M.G., Jonides, J., Kaplan, S., 2008. The cognitive benets of interacting with

nature. Psychol. Sci. 19 (12), 1207–1212. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-

9280.2008.02225.x.

C.D. Pierskalla et al.

Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 95 (2024) 128309

12

Berto, R., 2005. Exposure to restorative environments helps restore attentional capacity.

J. Environ. Psychol. 25 (3), 249–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2005.07.001.

Berto, R., 2007. Assessing the restorative value of the environment: a study on the elderly

in comparison with young adults and adolescents. Int. J. Psychol. 42 (5), 331–341.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00207590601000590.

Bringslimark, T., Hartig, T., Patil, G.G., 2009. The psychological benets of indoor

plants: a critical review of the experimental literature. J. Environ. Psychol. 29 (4),

422–433.

Brown, T.C., Daniel, T.C., 1987. Context effects in perceived environmental quality

assessment: scene selection and landscape quality ratings. J. Environ. Psychol. 7,

233–250.

Bruce, V., Green, P.R. (1990). Visual perception: Physiology, psychology and ecology

(2nd ed.). Hove and London, UK; Hillsdale, USA: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Publishers.

Cohen, J. (1969). Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences. New York:

Academic Press.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1975). Beyond Boredom and Anxiety. Washington: Jossey-Bass

Publishers.

Cuncic, A. (2021). How to cope when you are alone on Christmas. Verywell Mind.

https://www.verywellmind.com/how-to-cope-when-you-are-alone-at-christmas-

3024301#:~:text=In%20general%2C%20there%20are%20three%20ways%20to%

20cope,next%20year%20if%20you%20don%27t%20want%20to%20be.

Dalton, P., 1999. Cognitive inuences on health symptoms from acute chemical

exposure. Health Psychol. 18 (6), 579–590.

Dialsmith, L.L.C. (2023). Perception analyzer. https://www.dialsmith.com/dial-testing-

focus-groups-products-and-services/perception-analyzer-dial-research/.

Ewing, R., King, M.R., Raudenbush, S.W., Clemente, O.J., 2005. Turning highways into

main streets: two innovations in planning methodology. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 71 (3),

1–14.

Grinde, B., Patil, G.G., 2009. Biophilia: does visual contact with nature impact on health

and well-being? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 6 (9), 2332–2343. https://doi.

org/10.3390/ijerph6092332.

Hansen, M.M., Jones, R., Tocchini, K., 2017. Shinrin-yoku (forest bathing) and nature

therapy: a state-of-the-art 486 review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14, 1–48.

Hartig, T., Kaiser, F.G., Bowler, P.A. (1997). Further development of a measure of

perceived environmental restorativenesss. Working Paper No. 5. Institute for

Housing Research, Uppsala Universitet.

Heerwagen, J.H., Orians, G.H., 1993. Humans, habitats, and aesthetics. In: Kellert, S.R.,

Wilson, E.O. (Eds.), The biophilia hypothesis. Island Press, Washington, DC.

Herzog, T.R., 1984. A cognitive analysis of preference for eld-and-forest environments.

Landsc. Res. 9, 10–16.

Hilderbrandt, R., 1991. Marketing Christmas trees: implications of a Kansas study. J. For.

89 (7), 33–37.

Hung, S.H., Chang, C.Y., 2022. How do humans value urban nature? Developing the

perceived biophilic design scale (PBDs) for preference and emotion. Urban For.

Urban Green. 76, 127730 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2022.127730.

James, W. (1962). Psychology: The briefer course. New York, NY: Collier. (Original work

published 1892).

Kellert, S.R., Heerwagen, J., Mador, M., 2008. Biophilic Design: the Theory, Science and

Practice of Bringing Buildings to Life. Wiley, Hoboken, NJ. https://doi.org/10.5860/

choice.47-0092.

Jiang, S., 2022. Nature Through A Hospital Window: the Therapeutic Benets of

Landscape in Architectural Design. Routledge.

Joye, Y., Willems, K., Brengman, M., Wolf, K., 2010. The effects of urban retail greenery

on consumer experience: reviewing the evidence from a restoration perspective.

Urban For. Urban Green. 9, 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2009.10.001.

Kaplan, G.A., 1969. Kinetic disruption of optical texture: the perception of depth at an

edge. Percept. Psychophys. 6, 193–198.

Kaplan, R., Kaplan, S., 1989. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective.

Cambridge University Press.

Kaplan, S., 1995. The restorative benets of nature: toward an integrative framework.

J. Environ. Psychol. 15, 169–182.

Kaplan, S., 2001. Meditation, restoration, and the management of mental fatigue.

Environ. Behav. 33, 480–506. https://doi.org/10.1177/00139160121973106.

Kil, N., 2022. What is forest bathing? Curr. Univ. Wis. La Cross. 〈www.uwlax.edu/

currents/what-is-forest-bathing/〉.

Larson, R.B., 2004. Christmas tree marketing: product, price, promotion, and placed

tactics. J. For. 102 (4), 40–45.

Leenders, M., Smidts, A., Langeveld, M., 1999. Effects of ambient scent in supermarkets:

a eld experiment. Marketing and competition in the information age. Proc. 28

th

Eur. Mark. Acad. Conf. Humboldt. Univ. 1–8.

Lin, Y., Tsai, C., Scullivan, W.C., Chang, C., 2014. Does awareness effect the restorative

function and perception of street trees? Front. Psychol. 5 (906), 1–9. https://doi.org/

10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00906.

Lungman, T., Cirach, M., Marando, F., Pereira Barboza, E., Khomenko, S.,

Masselot, Piere, Quijal-Zamorano, M., Mueller, N., Gasparrini, A., Urquiza, J.,

Heris, M., Thondoo, M., Nieuwenhuiisen, M., 2023. Cooling cities through urban

green infrastructure: a health impact assessment of European cities. Lancet 401,

577–589. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02585-5.

Marples, M., 2021. These Christmas trees may. improve your health. 〈https://www.cnn.

com/2021/12/08/health/christmas-tree-mental-health-wellness/index.html〉.

Mayo Clinic, 2020. Stress, depress holiday. Tips coping. 〈https://www.mayoclinic.org/

healthy-lifestyle/stress-management/in-depth/stress/art-20047544〉.

Meredith, G.R., Rakow, D.A., Eldermire, E.R.B., Madsen, C.G., Shelley, S.P., Sachs, N.A.,

2020. Minimum time dose in nature to positively impact the mental health of

college-aged students, and how to measure it: a scoping review. Front. Psychol. 10,

2942. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02942.

Nasar, J.L. (Ed.). (1992). Environmental Aesthetics: Theory, Research, & Applications.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nguyen, T.T., Lee, E.E., Daly, R.E., Wu, T.C., Tang, Y., Tu, X., Van Patten, R., Jeste, D.V.,

Palmer, B.W., 2020. Predictors of Loneliness by Age Decade: Study of Psychological

and Environmental Factors in 2,843 Community-Dwelling Americans Aged 20-69

Years. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 81 (6), m13378. https://doi.org/10.4088/

JCP.20m13378.

Ofce of the Surgeon General (2023). Our epidemic of loneliness and isolation: The U.S.

Surgeon General’s advisory on the healing effects of social connection and

community [Internet]. Washington (DC): US Department of Health and Human

Services. PMID: 37792968.

Pasini, M., Berto, R., Brondino, M., Hall, R., Ortner, C., 2014. How to measure the

restorative quality of environments: The PRS-11. Soc. Behav. Sci. 129, 293–297.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.12.375.

Pierskalla, C.D., Deng, J., Siniscalchi, J.M., 2016. Examining the product and process of

scenic beauty evaluations using moment-to-moment data and GIS: the case of

Savannah. Ga. Urban For. Urban Green. 19, 212–222.

Qin, X., Meitner, M., Chamberlain, B., Zhang, X. (2008). Estimating visual quality of

scenic highway using GIS and landscape visualizations. ESRI press. In: Proceedings,

2008 ESRI Education Users Conference. August 2008, San Diego, California. p. 10.

(CD).

Rosenbaum, M.S., Ramirez, G.C., Camino, J.R., 2018. A dose of nature and shopping: the

restorative potential of biophilic lifestyle center designs. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 40,

66–73. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00906.

Sheppard, S.R.J. & Harshaw, H.W. (Eds.). (2001). Forests and Landscapes: Linking

Ecology, Sustainability, and Aesthetics. IUFRO Research Series, No. 6. Wallingford,

UK: CABI Publishing.

S

¨

oderlund, S., Newman, P., 2015. Biophilic architecture: a review of the rationale and

outcomes. AIMS Environ. Sci. 2 (4), 950–964.

Squire, D. (2002). The healing garden: Natural healing for mind, body and soul. Robson

Books Limited.

Strickland, B., Scholl, B.J., 2015. Visual perception involves ’event type’ representations:

the case of containment vs. occlusion. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 144 (3), 570–580.

Sturm, V.E., Datta, S., Roy, A.R.K., Sible, I.J., Kosik, E.L., Veziris, C.R., Chow, T.E.,

Morris, N.A., Neuhaus, J., Kramer, J.H., Miller, B.L., Holley, S.R., Keltner, D., 2022.

Big smile, small self: awe walks promote prosocial positive emotions in older adults.

Emotion 22 (5), 1044–1058. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000876.

Sun, Y., Molitor, J., Benmarhnia, T., Avila, C., Chiu, V., Slezak, J., Sacks, D.A., Chen, J.C.,

Getauhn, D., Wu, J., 2023. Association between urban green space and postpartum

depression, and the role of physical activity: a retrospective cohort study in Southern

California. Lancet 21, 100462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lana.2023.100462.

Szczygiel, B., Hewit, R., 2000. Nineteenth-century medical landscapes: John H. Rauch,

Frederick Law Olmsted, and the search for salubrity. Bull. Anesth. Hist. 74 (4),

708–734. https://doi.org/10.1353/bhm.2000.0197.

Ulrich, R.S., 1981. Natural versus urban scenes: some psychological effects. Environ.

Behav. 13, 523–556. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916581135001.

Ulrich, R.S., Simons, R.F., Losito, B.D., Fiorito, E., Miles, M.A., Zelson, M., 1991. Stress

recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J. Environ. Psychol.

11, 201–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80184-7.

Verde & Wharton (2015). The 2015 customer experience study reveals billions at risk for

retailers from negative CX. https://verdegroup.com/whitepapers/2015-Customer-

Experience-Risk-Study-Verde-Group.pdf.

Wang, R., Zhao, J., Meitner, M.J., Hu, Y., Xu, X., 2019. Characteristics of urban green

spaces in relation to aesthetic preference and stress recovery. Urban For. Urban

Green. 41, 6–13.

C.D. Pierskalla et al.