U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

Report to Congress on the Nation’s

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Workforce Issues

January 24, 2013

__________________________

Pamela S. Hyde, J.D.

Administrator

Table of Contents

Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 1

Introduction to Report ..................................................................................................................... 2

Background ..................................................................................................................................... 4

Changing Landscape: Impact on the Workforce ........................................................................... 5

Demographic Information ............................................................................................................... 7

Workforce Conditions ..................................................................................................................... 9

High Turnover ............................................................................................................................. 9

Worker Shortages ...................................................................................................................... 10

Aging Workforce....................................................................................................................... 11

Perceptions about Behavioral Health Conditions and Those with Lived Experience............... 11

Inadequate Compensation ......................................................................................................... 12

Compensation for Specialty Behavioral Health Providers ........................................................ 15

Data on Recruitment, Retention and Distribution ..................................................................... 15

Special Issues of the Prevention Workforce ............................................................................. 17

Impact of Affordable Care Act and MHPAEA on the Behavioral Health Workforce ............. 18

Enumeration of Needs................................................................................................................... 19

SAMHSA and HRSA Workforce Initiatives ................................................................................ 21

SAMHSA Workforce Programs................................................................................................ 21

HRSA Behavioral Health Workforce Programs ....................................................................... 39

SAMHSA - HRSA Workforce Collaborative Initiatives .......................................................... 40

SAMHSA/HRSA Joint Listening Session ................................................................................ 45

Conclusion .................................................................................................................................... 47

APPENDIX A: Examples of SAMHSA-HRSA Activities Related to Behavioral Health

Workforce – Listening Session Summary .................................................................................... 49

APPENDIX B: Bibliography ....................................................................................................... 56

1

SUBSTANCE ABUSE AND MENTAL HEALTH SERVICES ADMINISTRATION

REPORT TO CONGRESS ON THE NATION’S

SUBSTANCE ABUSE AND MENTAL HEALTH WORKFORCE ISSUES

January 24, 2013

Executive Summary

In its report on the fiscal year (FY) 2012 budget for the Department of Health and Human

Services (HHS), the Senate Appropriations Committee Subcommittee on Labor, Health, and

Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies (LHHS-ED) requested the Substance Abuse

and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) provide the Committee with a

workforce report, specifically addressing the addictions workforce and SAMHSA’s collaboration

with the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). The Subcommittee language is

as follows:

Addiction Services Workforce. – The Committee notes the growing workforce crisis in

the addictions field due to high turnover rates, worker shortages, an aging workforce,

stigma and inadequate compensation. The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity

Act and the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act are anticipated to increase the

number of individuals who will seek substance use disorder services and may exacerbate

current workforce challenges. As the provision of quality substance use disorder services

is dependent on an adequate qualified workforce and SAMHSA is the lead federal agency

charged with improving these services, the Committee expects SAMHSA to focus on

developing the addiction workforce and identify ways to address the current and future

workforce needs of the addiction field. The Committee directs SAMHSA to submit a

report by March 31, 2012, on current workforce issues in the addiction field, as well as

the status and funding of its substance use disorder services workforce initiatives. This

report should also detail how SAMHSA is working with HRSA to address addiction

service workforce needs and should identify the two agencies’ specific roles,

responsibilities, funding streams and action steps aimed at strengthening the addiction

services workforce (Senate Report 112-84, page 122).

SAMHSA has prepared this report to Congress to provide an overview of the facts and issues

affecting the substance abuse and mental health workforce in America. While the workforce

report was requested specifically for the addiction treatment workforce, SAMHSA’s report will

cover the behavioral health workforce in its entirety because many data sources (including those

funded by HRSA’s Bureau of Health Professions and the Department of Labor) and programs

report by profession or discipline rather than population served (e.g., social workers,

psychologists, and counselors), whether providing prevention services or treatment and whether

serving persons with substance use disorders, mental health conditions, or both. Data specific to

the substance use disorder treatment workforce will be provided wherever available. This report

also will include demographic data as well as a discussion of key issues and challenges such as

staff turnover, aging of the workforce, inadequate compensation, worker shortages, licensing and

credentialing issues, and recruitment, retention and distribution of the workforce. The

misunderstandings and often inaccurate perceptions of society about mental illness and addiction

2

as these relate to workforce challenges are also discussed. The information on the behavioral

health

1

workforce is drawn from multiple resources as there is no single federal data source at

this point in time.

The impact of the Affordable Care Act and the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act

(MHPAEA), which will increase access and alter service settings, is also discussed. The

enactment of both of these laws may reshape the workforce and the delivery of services. For

example, the Affordable Care Act is moving the field toward the integration of services with

primary care, which has significant workforce implications in regard to team approaches and the

new roles and responsibilities for staff. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) projections made prior

to the passage of MHPAEA and Affordable Care Act already indicated higher than normal

growth for a number of behavioral health professions.

This report also describes SAMHSA’s efforts to address many of these issues through its current

programs and its eight Strategic Initiatives. In addition, the report presents a summary of

collaborations between SAMHSA and HRSA, including a jointly sponsored listening session on

the behavioral health workforce. HRSA and SAMHSA have worked collaboratively to address

behavioral health workforce issues by sharing information about efforts within each agency and

by developing, funding, and managing joint projects such as the Center for Integrated Health

Solutions (CIHS), the minimum data set (MDS) project, and the training of practitioners about

military culture to enhance service provision for veterans and their families. Many of these

projects and efforts are described in this report.

SAMHSA is keenly aware that to achieve its mission to reduce the impact of substance abuse

and mental illness on America’s communities, a well-trained, educated and fully functioning

workforce is needed. Likewise, HRSA is aware that to achieve its mission to improve health and

achieve health equity through access to quality services, a skilled health workforce and

innovative programs, it must address behavioral health as an essential part of the health care

landscape in America. SAMHSA and HRSA are working

together toward these aims.

Intr

oduction to Report

An adequate supply of a well-trained workforce is the foundation for an effective service

delivery system. Workforce issues, which have been of concern for decades, have taken on a

greater sense of urgency with the passage of recent parity and health reform legislation.

SAMHSA is fully cognizant of the impact that workforce issues have on the infrastructure of the

1

In this report, the term “behavioral health” is used to encompass mental health conditions, mental illness,

substance abuse, substance use disorders, and addictions. In various contexts, the term is used to include emotional

health development, substance abuse and mental illness prevention services and activities, treatment services, and/or

recovery support activities and services for those in recovery from mental illness, mental health problems, and/or

addictions.

3

behavioral health delivery system and services, and seeks to address these issues through a

variety of initiatives and programs. SAMHSA also recognizes that increasing the size of the

workforce, recruiting a more diverse, younger workforce, and retaining trained and qualified

staff are necessary to provide for the behavioral health needs of the nation’s population.

In the past decade, SAMHSA commissioned workforce reports to identify major workforce

issues and develop recommendations to address these challenges. These reports, An Action Plan

for Behavioral Health Workforce Development (SAMHSA, 2007), Report to Congress:

Addiction Treatment Workforce Development (SAMHSA, 2006), and Strengthening Professional

Identity: Challenges of the Addition Treatment Workforce (SAMHSA, 2006a), led to the

continuing support of some existing programs and the development of some new workforce

efforts. Behavioral health workforce initiatives focus on technology transfer and training on

evidence-based practices, providing resources, supporting knowledge transfer, recruiting a

diverse workforce, and integrating primary and behavioral health care.

Since the publication of SAMHSA’s workforce reports, there have been a number of changes

that increase the need and demand for behavioral health services. The Affordable Care Act will

increase the number of people who are eligible for health care coverage through Medicaid and

Exchanges and includes parity for services within its covered services. In addition, as screening

for mental illness and substance abuse become more commonplace in primary care, more people

will be identified as needing services. Furthermore, workforce shortages will be impacted by

additional demands that result from: (1) a large number of returning veterans in need of services;

and (2) new state re-entry initiatives to reduce prison populations, a large majority of whom have

mental or substance use disorders.

Preparing a workforce that can meet the challenges of the 21

st

century is an essential component

of SAMHSA’s strategic plan and programs. SAMHSA has embedded workforce elements in

each of the eight Strategic Initiatives, as described in its strategic plan document, “Leading

Change: A Plan for SAMHSA's Roles and Actions 2011-2014,” (SAMHSA, 2011a). Examples

of workforce objectives in each of the Strategic Initiatives include:

1. Prevention of Substance Abuse and Mental Illness: Educate the behavioral health field

about successful interventions, such as screening, brief intervention, and referral to

treatment (SBIRT); and develop and implement training around suicide prevention and

prescription drug abuse.

2. Trauma and Justice: Provide technical assistance and training strategies to develop

practitioners skilled in trauma and trauma-related work and systems that have capacity to

prevent, identify, intervene and effectively treat people in a trauma-informed approach.

3. Military Families: Develop a public health-informed model of psychological health

service systems, staffed by a full range of behavioral health practitioners who are well

trained in the culture of the military and the military family and the special risks and

needs that impact this population, such as Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI). The role of peer counselors within this model will also be

important to its success.

4. Recovery Support: Build an understanding of recovery-oriented practices, including

incorporating peers into the current workforce to support peer-run services. Emphasize

4

collaborative relationships with children, youth, and families that involve shared

decision-making service options.

5. Health Reform: Work with partners and stakeholders to develop a new generation of

providers, promote innovation of service delivery through primary care and behavioral

health care integration, and increase quality and reduce health care costs through health

insurance exchanges and the essential and benchmark benefit plans.

6. Health Information Technology: Promote the adoption of electronic health records

(EHRs) and the use of health information technology (HIT) through SAMHSA’s

discretionary program and Block Grant technical assistance efforts.

7. Data, Outcomes and Quality: Target quality improvement through workshops, intensive

training and resources that promote the adoption of evidence-based practices, and

activities to advance the delivery of clinical supervision to foster competency

development and staff retention.

8. Public Awareness and Support: Ensure that the behavioral health workforce has access

to information needed to provide successful prevention, treatment, and recovery services.

Background

The Institute of Medicine (IOM; 2006) chronicles efforts beginning as early as the 1970s that

attempt to deal with some of the workforce issues regarding mental and substance use disorders,

but notes that most have not been sustained long enough or been comprehensive enough to

remedy the problems. Shortages of qualified workers, recruitment and retention of staff and an

aging workforce have long been cited as problems. Lack of workers in rural/frontier areas and

the need for a workforce more reflective of the racial and ethnic composition of the U.S.

population create additional barriers to accessing care for many. Recruitment and retention

efforts are hampered by inadequate compensation, which discourages many from entering or

remaining in the field. In addition, the misperceptions and prejudice surrounding mental and

substance use disorders and those who experience them are imputed to those who work in the

field.

Of additional concern, a new IOM report (2012) notes that the current workforce is unprepared

to meet the mental and substance use disorder treatment needs of the rapidly growing population

of older adults. The IOM report’s data indicate that 5.6 to 8 million older adults, about one in

five, have one or more mental health and substance use conditions which compound the care

they need. However, there is a dearth of mental health or substance abuse practitioners who are

trained to deal with this population.

Pre-service education and continuing education and training of the workforce have been found

wanting, as evidenced by the long delays in adoption of evidence-based practices, under-

utilization of technology, and lack of skills in critical thinking (SAMHSA, 2007). These

education and training deficiencies are even more problematic with the increasing integration of

primary care and mental or substance use disorder treatment, and the focus on improving quality

of care and outcomes. As noted by the IOM (2003), all health care personnel, including

behavioral health clinicians, should be trained “to deliver patient centered care as members of an

5

interdisciplinary team, emphasizing evidence-based practice, quality improvement approaches

and informatics.”

Data reported in the 2010 and 2011 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH)

demonstrates the current unmet need for behavioral health services:

• Approximately 21.6 million persons aged 12 or older (8.4 percent of this population)

needed treatment for an illicit drug or alcohol use problem.

• Only 2.3 million (10.8 percent) of those who needed treatment received treatment at a

specialty facility (SAMHSA, 2012b).

• Approximately 45.9 million adults aged 18 or older (20 percent of adults) in the United

States had any mental illness in the past year.

• Approximately 11.1 million adults aged 18 or older (4.9 percent of adults) reported an

unmet need for mental health care in the past year including 5.2 million adults aged 18 or

older who reported an unmet need for mental health care and did not receive mental

health services in the past year.

• Inability to afford care was cited as the most significant barrier to receiving care for

mental health services (43.7 percent of those surveyed who needed services); the lack of

coverage and cost of services was cited as a significant barrier in seeking substance use

disorders services (32.9 percent of those surveyed who needed services for a substance

use disorder (SAMHSA, 2011).

As indicated in the NSDUH data above, many individuals who may need behavioral health

services do not access them due to lack of health care coverage. However, health reform will

significantly reduce this barrier to behavioral health services. It is estimated that approximately

11 million of the individuals who will have access to coverage beginning in 2014 will have

mental and/or substance use disorders and will have access to care with the continued

implementation of health reform (SAMHSA, 2011). This increase is expected to strain an

already thinly stretched workforce.

In the absence of any available standardized survey instrument or national study that provides the

needed information, data for this report are taken from a number of sources. There are two

SAMHSA sponsored initiatives that will address the paucity of standardized workforce data.

SAMHSA and HRSA are working collaboratively on the development of a MDS, starting with

the major behavioral health professional disciplines, which may ameliorate the data scarcity

problem in the future. In addition, SAMHSA’s Addiction Technology Transfer Centers

(ATTCs) conducted a national workforce survey on the addiction treatment workforce which

was completed at the end of FY 2012.

Changing Landscape: Impact on the Workforce

In addition to the enactment of parity and health reform legislation, advancements in research,

demand for outcomes and quality improvements, and the empowerment of people in recovery are

contributing to changes in practice and the workforce. Major changes to the field include the

integration of behavioral health and primary care, a push to accelerate the adoption of evidence-

6

based practices, and a model of care that is recovery-oriented, person-centered, integrated, and

utilizes multi-disciplinary teams. Behavioral health has moved to a chronic care, public health

model to define needed services. This model recognizes the importance of prevention, the

primacy of long-term recovery as its key construct, and is shaped by those with lived experience

of recovery. This new care model will require a diverse, skilled, and trained workforce that

employs a range of workers, including people in recovery, recovery specialists, case workers and

highly trained specialists.

Integrated care will reduce medical costs and result in better outcomes. One study showed that

individuals with the most serious mental illnesses and co-occurring disorders living in publicly

funded inpatient facilities die at age 53, on average (Parks et al., 2006). A more recent study,

using a population based representative sample, found that people with mental health disorders

died on the average eight years younger than those without mental health disorders and these

deaths were largely due to medical causes rather than accidents or suicides (Druss et al., 2011).

People with mental and substance use disorders die from treatable medical conditions such as

smoking, obesity, high blood pressure and a variety of other medical disorders (Mertens et al.,

2003). Untreated mental and substance use disorders not only negatively impact a person’s

behavioral health but also lead to worse outcomes for co-occurring physical health problems.

Though the co-occurrence of behavioral and other medical conditions is common, individuals

with serious behavioral health conditions who lack financial resources are often unable to access

quality care, either for their behavioral health conditions or for other health problems. Good

behavioral health is associated with better physical health outcomes, improved educational

attainment, increased economic participation, and meaningful social relationships. Further, good

health is not possible without good behavioral health (Friedli & Parsonage, 2007). Receipt of

behavioral health treatment has been shown to decrease medical care costs significantly (Gerson

et al., 2001). Thomas (2006) reported savings of $140 per enrollee per month when coordinated

care was provided for high-cost, high-risk Medicaid patients with depression. This coordinated

care resulted in a 12.9 percent reduction in cost for this population. Unützer et al. (2008) found

that providing coordinated depression and primary care for older adults resulted in reduced

symptoms of depression in 45 percent of patients and reduced the per patient care cost an

average of $3,000 over four years.

Another significant change in health care is the use of SBIRT. As health reform takes effect,

SBIRT will become a part of the ongoing prevention activities resulting in the identification of

many more people with, or at risk for, depression and substance use disorders. Many individuals

who are identified will receive brief interventions or brief treatment, often conducted by health

educators, recovery specialists or other types of staff in the primary care system. Those needing

more intensive treatment/recovery services would be referred to specialty treatment

providers/practitioners.

The behavioral health care workforce is a complex system, comprising many different

professionals ranging from psychiatrists to non-degreed workers and para-professionals. The

integration of primary and behavioral health care will impact both the behavioral health and the

primary care workforce as primary care staff will be expected to have competencies in

behavioral health and behavioral health staff will need competencies associated with working in

7

primary care settings. A study done by the National Association of Community Health Centers

(NACHC; 2011) found that 43 percent of physicians working in Federally Qualified Health

Centers (FQHCs) were interested in training on medication assisted treatments for persons with

addictive disorders. Many FQHC staff also indicated interest in training on Motivational

Interviewing, Short-term Interventions, Problem-Focused Treatment, SBIRT, PTSD and trauma

interventions.

Trauma plays a central role in behavioral health disorders. Exposure to physically or

psychologically harmful or life-threatening events is a common risk factor for both mental and

substance use disorders (SAMHSA, 2004). Studies have also linked the experience of trauma to

other chronic physical diseases, such as obesity, diabetes and pulmonary diseases (Felitti et al.,

1998). Individuals with significant trauma histories are present not only in the behavioral health

specialty sector, but in child welfare, criminal and juvenile justice, domestic violence, education

and primary and specialty health care. Emerging studies have begun to document positive

outcomes in these sectors when trauma is addressed and appropriately treated. SAMHSA has

recognized the public health urgency to more systematically address trauma. Investments have

been made in the development of education and public awareness materials, screening and

assessments, treatment and recovery interventions, and organizational approaches to trauma.

Critical to this effort is the development of a workforce trained in trauma-specific or trauma-

informed approaches.

In addition, the shift to a recovery-oriented paradigm has resulted in an increased use of peers,

recovery support workers, care managers, patient navigators, and health educators. The role of

peer specialists is to provide ongoing recovery support for people with mental or substance use

disorders. As of September 2011, 23 states have developed certification programs for peer

specialists. Certified Peer Specialists/Recovery Coaches may work in many settings including

independent recovery community organizations, partial hospitalization or day programs,

inpatient or crisis centers, vocational rehabilitation or drop-in centers, residential programs, and

medication assisted programs. Peer support activities include self-determination and personal

responsibility, providing hope, recovery coaching, life skills, training, communication with

providers, health and wellness, illness management, addressing discrimination and promoting

full inclusion in the community, assistance with housing, education/employment, and positive

social activities (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment [CSAT], 2009; Daniels et al., 2011).

Demographic Information

This section will provide data on gender, race and educational level of the mental health and

addictions workforce.

8

Gender

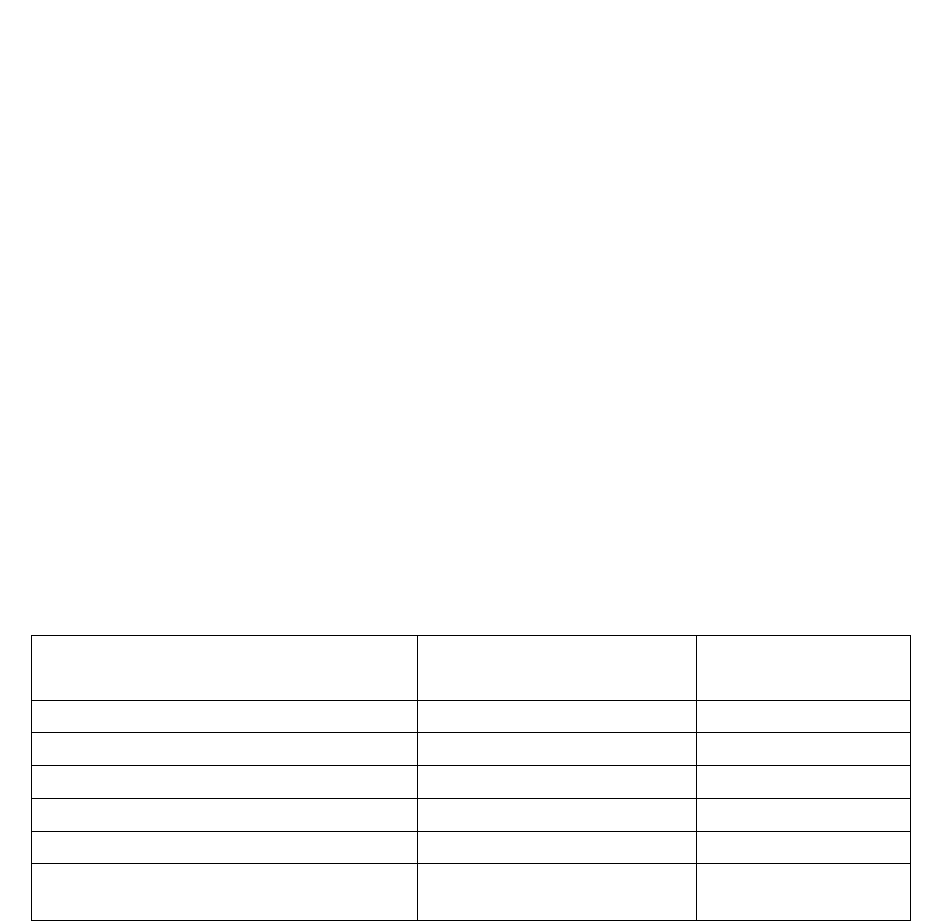

The gender breakdown for some of the major professions working in the field is listed in Table 1.

Table 1

Occupation

Male

Female

Psychologists

33.5%

66.5%

Psychiatrists

70%

30%

Social Workers

19.2%

80.8%

Counselors

28.8%

71.2%

Bureau of Labor Statistics, Department of Labor, Occupational Outlook Handbook 2010-11 http://bls.gov/oco/

A sample of 260 Certified Peer Specialists from 28 states found that 33 percent were male and

66 percent were female, and one percent reported they were transgender (Salzer et al., 2010).

Similar data were found in several studies that looked at turnover and other staffing issues in the

addictions field. These studies reported the percentage of women in the addiction treatment field

at 60 percent or higher (Knight et al., 2012; Knudsen et al., 2006; Curtis & Eby, 2010).

Information obtained by the International Certification and Reciprocity Consortium (IC&RC)

from 15 certification boards

2

reporting on 30,742 counselors found that 61.9 percent were

women and 38.1 percent were men (2011).

Racial Composition

Racial and ethnic minorities as a whole comprise approximately 30 percent of the U.S.

population (U.S. Census, 2010), and a similar percentage of those receiving services (SAMHSA,

2012; 2008). However, African Americans are represented at a higher rate among service

recipients for both mental health and addictions services. As indicated in Mental Health, United

States, 2010 (SAMHSA, 2012a) report, racial minorities account for only:

• 19.2 percent of all psychiatrists;

• 5.1 percent of psychologists;

• 17.5 percent of social workers;

• 10.3 percent of counselors; and

• 7.8 percent of marriage and family therapists.

Information reported from eight certification boards which are members of IC&RC, representing

21,681 counselors as of March 1, 2012, found the racial makeup as described in Table 2 below.

2

There are credentialing boards for addiction counselors in all 50 States; however, not all of them collect data on a

consistent basis nor do they all collect data on the same variables. Therefore in several places in this Demographic

Information section the numbers of certification boards responding may vary.

9

Table 2

Racial Composition

Race

Percent

White

55.8%

Black/African-American

27.9%

Hispanic/Latino

11.1%

American Indian/Alaska Native

0.7%

Asian/Pacific Islander

2.8%

N = 21,681 from 8 boards.

A sample of certified peer specialists found that 21 percent of those respondents were from

minority populations (Salzer et al., 2010). The ongoing disparity in the demographics of the

workforce and patient population suggest that training in cultural competence will be important.

Education Levels

Dilonardo (2011) reported that almost all states (98 percent) required a master’s degree to qualify

as a mental health counselor but 45 percent of states did not require any college degree to qualify

as a substance abuse counselor. For behavioral health care disciplines, independent practice

requires a master’s degree in most states; however, for addiction counselors, data available a

decade ago indicated that about 50-55 percent of those certified or practicing in the field had at

least a master’s degree, 75 percent hold a bachelor’s degree, and the reminder had either some

college, a high school diploma or equivalent (Kaplan, 2003).

Workforce Conditions

This section briefly summarizes some of the major factors that impact the workforce, including

high turnover, worker shortages, an aging workforce, inadequate compensation, and recruitment,

retention and distribution of the workforce, as well as misperception and prejudice about mental

illness and addiction.

High Turnover

Staff turnover is costly in monetary terms with regard to replacement expenses and also

disruptive to the therapeutic relationship. SAMHSA’s workforce studies (2007, 2006, 2006a) all

found high turnover rates reported in the literature at those times. Recent studies corroborate

those earlier findings. The 2012 ATTCs workforce survey reported an average annual turnover

of addiction services professionals at 18.5 percent across the country (Ryan et.al., 2012). Eby et

al. (2010) conducted a study of 739 clinicians over a two-year time period in 27 geographically

dispersed public and private treatment organizations and found annual turnover rates of 33.2

percent for counselors and 23.4 percent for clinical supervisors. A study of adolescent treatment

programs (Garner et al., 2012) found turnover rates of 31 percent for clinicians and 19 percent

for clinical supervisors. These rates are substantially higher when compared to primary care

10

physicians in managed care organizations who had a median turnover rate of approximately

seven (7.1) percent (Plomondon et al., 2007). As reported by Anderson (2012), nurse

practitioners and physicians assistants had 12 percent turnover rates.

A meta-analysis found that burn-out, stress and lack of social support are antecedents to worker

turnover in the social service sector (MorBarak et al., 2001). Other studies found that better

opportunities were key reasons for leaving (Eby et al., 2010; Gulf Coast ATTC, 2005). Reported

turnover appeared to be worse in rural agencies (Knudsen et al., 2005). Another study by Knight

et al. (2012) demonstrated that high turnover produced increased stress and workforce demand

for the remaining staff. One study found that clinical supervision reduced emotional exhaustion

and turnover intention in counselors working in treatment agencies (Knudsen et al., 2008).

In a Gulf Coast ATTC survey, directors reported annual staff turnover rate was 42 percent. The

leading reason for leaving was a better opportunity in the field, followed by personal reasons

(illness, family issues, child care, etc.), and inadequate salary. In 2004, program directors in

Tennessee reported turnover rates from 15-22 percent. Reported turnover appeared to be higher

in rural agencies (Knudsen et al., 2005).

High turnover most often had a negative impact on implementation of evidence-based practices,

although some teams were able to use strategies to improve implementation through turnover.

Implementation models must consider turbulent behavioral health workforce conditions

(Woltmann et al., 2009). Carise et al., (2005) worked with nine community-based treatment

centers in Philadelphia to implement a new assessment tool and had trouble recruiting staff for

the study due to staff turnover rates of 32 percent among the agencies involved.

Worker Shortages

Concerns about worker shortages have been indicated for a number of years. As reported in An

Action Plan for Behavioral Health Workforce Development (SAMHSA, 2007), it is projected

that by 2020, 12,624 child and adolescent psychologists will be needed but a supply of only

8,312 is anticipated. Mental Health, United States, 2008 (SAMHSA, 2010), found more than

two-thirds of primary care physicians who tried to obtain outpatient mental health services for

their patients reported they were unsuccessful because of shortages in mental health care

providers, health plan barriers, and lack of coverage or inadequate coverage.

As of March 30, 2012, HRSA reported that there were 3,669 Mental Health, Health Professional

Shortage Areas (HPSAs)

3

containing almost 91 million people. It would take 1,846 psychiatrists

and 5,931 other practitioners to fill the needed slots. This shortage of workers is not evenly

distributed as 55 percent of U.S. counties, all rural, have no practicing psychiatrists,

psychologists, or social workers (SAMHSA, 2007). Another study (Thomas et al., 2009) found

that 77 percent of counties had a severe shortage of mental health workers, both prescribers and

non-prescribers and 96 percent of counties had some unmet need for mental health prescribers.

3

The Mental Health HPSAs do not include consideration of shortages of specialty addiction services professionals.

11

The two characteristics most associated with unmet need in counties were low per capita income

and rural areas.

Ascertaining the supply of addiction treatment workers has been difficult due to a lack of

ongoing data collection. In surveys conducted by various regional ATTCs, program directors

have indicated problems recruiting adequately prepared staff, often citing at least one or more

unfilled full time equivalent (FTE) positions (RMC, 2003; Knudsen et al., 2005). Reasons for

recruiting difficulties include insufficient numbers of applicants who meet minimum

qualifications (due to lack of experience, certification, or education), a small applicant pool in

specific geographic areas, and a lack of interest in the positions due to salary and limited funding

(Ryan et al., 2012; Gulf Coast ATTC, 2007). In addition, the Gulf Coast study found that even if

all of the 105 positions were filled, 34 percent of agencies would still be understaffed. Agencies

reported a need for 56 additional budgeted positions statewide. A survey of agencies in

Tennessee conducted by the Central East ATTC (Knudsen et al., 2005) found that program

directors reported an average staff shortage of 1.27 FTEs across programs.

Aging Workforce

According to the BLS the median age of various professionals who work in the mental health

and addiction field are shown in Table 3 below.

Table 3

Occupation

Median Age

Psychologists

50.3

Psychiatrists

55.7 (46% are 65+)

Social Workers

42.5

Counselors

42

Bureau of Labor Statistics, Department of Labor, Occupational Outlook Handbook 2010-11 http://bls.gov/oco/

In 2006, more than 50 percent of male U.S. psychiatrists and 25 percent of female psychiatrists

were aged 60 or older (SAMHSA, 2010). Recent studies, using samples of hundreds of

counselors across programs in many states, reported consistent findings for counselors working

in addiction treatment, with an average age in the mid-40s (Knight et al., 2012; Knudsen et al.,

2006). The current addiction treatment workforce is middle-aged and even new workers entering

the field do so relatively late in their careers (RMC, 2003; RMC, 2003a; National Association for

Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Counselors [NAADAC], 2003). Many counselors come into the

field as second careers, entering the profession in their mid-forties (SAMHSA, 2006a).

Recruiting students into the field, particularly from under represented populations, can serve as a

counterbalance to an aging workforce.

Perceptions about Behavioral Health Conditions and Those with Lived Experience

People with mental and substance use disorders often face misunderstanding and discrimination

for having these conditions. Those working in the behavioral health field often face the same

misperceptions and judgments about their value as clinicians which results in recruitment

12

difficulties and lower pay than comparable fields (National Council of Community Health

Centers [NCCBHC], 2011; SAMHSA, 2007; SAMHSA, 2006).

A 2011 compensation study found that the negative beliefs and misunderstandings associated

with people suffering mental illnesses and substance use disorders also impacts those working in

the field, even as compared to other segments of health care. At a mental health center, a

master’s level social worker earns $45,344 and an entry level social worker earns $30,000 while

in a general health care agency, a social worker earns $50,470. A registered nurse working in a

behavioral health organization makes $52,987 while the national average for nurses is $66,530

(NCCBH, 2011).

Most staff in a Northwest Frontier ATTC survey reported that they had lower professional status

than other health professionals (RMC, 2003). A series of focus groups throughout New York

State indicated that the prejudice and misunderstanding of alcoholism and drug addiction

prevents other professions from recognizing and accepting addictions professionals as peers

(New York State Office of Alcoholism and Substance Abuse Services [NYS OASAS], 2002).

As discussed in the workforce survey conducted in Texas (Gulf Coast ATTC, 2007), the

perception that addictions counselors have low status may also contribute to professionals

leaving the field and difficulty in recruiting replacements. Seventy-five percent of directors

thought that addictions counselors have lower status than other helping professionals and only

four percent thought that addictions counselors have higher status. Among those who thought

status was lower, the primary reason was that addictions counselors have less formal education

or training.

A number of workforce studies conducted in the past decade found that addiction counselors had

lower status than other professionals (NYS OASAS, 2002; RMC, 2003; Gulf Coast ATTC,

2007). Knudsen et al. (2005) also reported that some clinicians may also have lower status due

to their own history of substance use disorders. In a series of focus groups conducted primarily

with African-American and Hispanic early and mid-career populations, participants stated that

addictions treatment was not valued in the larger society and that, therefore, workers were not

well compensated or offered supports to avoid burn-out. The lack of information about the field

and the perception that the field is not viewed as a valued profession appear to be recruitment

barriers for some individuals (Gaumond et al., 2007).

Inadequate Compensation

Compensation for those working in behavioral health is significantly lower than for other health

related or other comparable professions. The National Council for Community Behavioral

Healthcare (NCCBH) has a membership of over 1,950 community-based, largely non-profit

providers delivering both mental health and substance abuse services for persons with mental

illness, addictive disorders or both. A 2011 survey conducted by the NCCBH found a strong

positive relationship between salary and organizational size/revenue. In addition, geographic

differences in salaries were noted, especially with those in the Northeast when compared to the

rest of the county. Also, psychiatrists working in rural settings had higher salaries compared to

psychiatrists working in other locations. The NCCBH study also found differences in executive

13

salaries, with the vast majority of executive salaries at mental health centers below $150,000.

The average salary of a Chief Executive Officer (CEO) at a community mental health center was

$114,247, compared to $136,168 for a CEO at a FQHC. Both of these were significantly less

than the top management official at a non‐profit hospital, which was $408,927.

This survey also found that salaries for positions in behavioral health care were much lower than

reference professions both in other service areas within the health care industry and outside

health care. For example, a licensed professional social worker, requiring a Master’s degree and

typically 2,000 hours of post-graduate experience, earned less than the manager of a fast food

restaurant. The median salary for a direct care worker in a 24-hour residential treatment center

was $23,000 compared to $25,589, the median salary for an assistant manager at Burger King

(NCCBH, 2011).

Compensation for those working in the addictions field is notoriously low. In fact, earlier studies

(Kaplan, 2003) suggested that inadequate compensation contributes to high turnover with

counselors engaging in significant churning or movement from one job to another to increase

their salaries, often by only $1,000 a year. NAADAC (2006) noted that “[m]any of our

Addiction Professionals across the USA can currently qualify for food stamps - this is not

acceptable - especially if we want quality, competent and long-term professionals.” The

disparity in the salary for substance abuse counselors and other professional groups is due in part

to the difference in credentialing/ licensure standards. The lack of national standards for

addiction counselors and the absence of any specific degree requirements across many states

impact the overall compensation for this group of workers.

Average wages for behavioral health professionals are shown in Table 4.

Table 4

Average Wages from the Bureau of Labor Statistics

Profession

Bureau of Labor

Statistics*

National Council

Salary Survey

Psychiatrists

$163,660

$168,163

Psychologists

$84,220

$79,900

Marriage & Family Therapists

$49,020

$42,605

Social Worker (MSW)

$50,470

$45,344

Mental Health Counselors (MA)

$41, 710

$41,313

Substance Abuse & Behavioral

Disorders Counselors (Certified/BA)

$37,030

$34,331

* Bureau of Labor Statistics, - Occupational Outlook Handbook 2009

Fo

r comparative purposes, the NCCBH in its 2011 salary survey looked at average salaries for

selected professions that required comparable education and training to the professions listed in

Table 4 for those disciplines that required a master’s degree or less. The selection provides a

comparison of average salaries between standard behavioral health professions and allied

health/public service workers. These are shown in Table 5.

Table 5

14

Average Wages of Reference Professions

Reference Profession

Average Wage

Physician Assistant

$84,830

Physical Therapist

$76,220

Dental Hygienist

$67,860

Secondary School Teacher

$55,150

Subway /Metro Operator

$52,800

Firefighters

$47,270

BLS found similar low wages in Table 6 below.

Table 6

Profession

Median Wage

Psychiatrists

$164,220

Psychologists

$63,140

Marriage & Family Therapists

$44,590

Mental Health and Substance Abuse

Social Workers

$37,210

Substance Abuse & Behavioral

Disorders Counselors

$37,030

Mental Health Counselors

$36,810

Bureau of Labor Statistics, Department of Labor, Occupational Outlook Handbook 2010-11 http://bls.gov/oco/

The middle 50 percent of substance abuse and behavioral disorders counselors earned between

$29,410 and $47,290. The lowest 10 percent earned less than $24,240, and the highest 10

percent earned more than $59,460. Median annual wages in the industries employing the largest

numbers of substance abuse and behavioral disorder counselors were as follows:

Table 7

Wages by Setting

Setting

Median Wage

General medical and surgical hospitals

$44,130

Local government

$41,660

Outpatient care centers

$36,650

Individual and family services

$35,210

Residential mental retardation, mental

health and substance facilities

$31,300

Bureau of Labor Statistics, Department of Labor, Occupational Outlook Handbook 2010-11 http://bls.gov/oco/

15

A column in an online employment service cited chemical dependency counseling as one of the

five most high stress and low paying jobs in the country.

4

The median annual salary it reported

was $38,900 with annual salaries ranging from $25,079-$48,517. As reported in this column,

many counselors deal with addicted individuals who are often mandated to treatment, and who

do not want any interventions.

“While the work can be compelling, substance-abuse counseling ranks as one of the most

difficult social work jobs due to its emotional challenges. Watching clients relapse and

sometimes become ill or die can take its toll. The combination of being stressed out and broke

trumps all other career-related gripes.” Unfortunately, as with chemical-dependency counselors

or parole officers, many of the workers dealing with high stress and low pay provide essential

social services. “We can't have a society with no probation officers, no social workers,” says Al

Lee, director of quantitative analysis at PayScale.com. We should maybe talk about where we

want to spend our money as a society” (Leonardi, 2012).

Compensation for Specialty Behavioral Health Providers

Congress determined long ago that community health providers funded by HRSA to serve those

without access to other health care and often without insurance should be compensated at cost.

These providers receive grants through HRSA and special and higher rates through Medicaid if

they are determined to be FQHCs meeting HRSA-determined criteria for service provision and

quality. On the other hand, community mental health and substance abuse providers do not have

to meet federally determined criteria for service provision and quality. They must meet state

certification or credentialing requirements which vary from no special requirements to extensive

requirements. These state credentialed providers serve a disproportionate number of low-income

and uninsured individuals and are often reimbursed through Medicaid or through state block

grants (administered through SAMHSA) at whatever rate or for whatever budget the particular

state offers, regardless of the cost of delivering that care.

Likewise, community behavioral health is generally not structured as physician-based practices

the way private sector practitioners are structured. Hence, the incentives for development and

use of health information technology have not been funded for community behavioral health

providers as they have for hospitals or practitioner-based providers. The inconsistency in

funding for FQHCs and community-based behavioral health care providers makes recruiting and

retaining practitioners particularly difficult for these specialty providers serving some of the

nation’s most-in-need persons with addictions and/or mental illness.

Data on Recruitment, Retention and Distribution

As cited in the major SAMHSA workforce report of 2007, An Action Plan for Behavioral Health

Workforce Development, “[e]xamining workforce need nationally is complicated by a host of

factors. There is no national census on behavioral health workforce that adequately captures the

number of trained or employed individuals.” As mentioned previously, this lack of data on the

4

All salary data are provided by online salary database PayScale.com. Salaries listed are median, annual salaries

for full-time workers with five to eight years of experience and include all bonuses, commissions or profit-sharing.

16

workforce has been a major challenge in documenting workforce demand and supply. There is a

paucity of information on recruitment. The extensive SAMHSA 2007 Action Plan report found

that the existing literature focused on engaging minorities in graduate-level training.

Recruitment efforts are not well documented and little data exists on results of recruitment

initiatives. Some workforce studies that were conducted specifically on the addiction workforce

reported that staff recruitment was hampered by low salaries as cited by a majority of program

directors surveyed (RMC, 2003; RMC, 2003a; NYS OASAS, 2002). Management staff also

reported that candidates often did not meet the minimum job requirements due to lack of training

and education or experience in substance abuse treatment. In a workforce report conducted in

Texas in 2007, program directors cited the primary reasons for recruiting difficulties are

insufficient numbers of applicants who meet minimum qualifications due to lack of experience,

certification, or education (Gulf Coast ATTC, 2007).

More literature exists on retention of staff; however, most of the literature focuses only on the

addiction services workforce. In these studies, the turnover rates range from 18.5 percent

(Knudsen et al., 2003) to over 50 percent (McLellan et al., 2003). Kaplan (2003) found that

inadequate compensation contributed to high turnover of addiction counselors which resulted in

movement from one job/agency to another in search of salary increases.

Growth across the behavioral health professions is not consistent. As cited in Mental Health,

United States, 2002 (Sullivan et al., 2004), an increase in the number of both psychologists and

social workers has been noted for years, and, as noted on page 12, the number of psychiatrists

has been stable and therefore not keeping up with the growth in population. As Table 8

demonstrates, the projected growth identified by the BLS for behavioral health occupations is in

many cases greater than the average for most occupations. Given that there are many reports that

cite workforce shortages for addiction counselors, it is clear that strategies need to be developed

to address the field’s recruitment issues.

Table 8

Projected Growth of Specific Occupations

Profession

2008 Workforce

2018 Projection

Increase

Substance Abuse & Behavioral

Disorders Counselors*

86,100

104,200

18,100 (21%)

Mental Health Counselors*

113,000

140,400

27,200 (24%)

Mental Health & Substance

Abuse Social Workers

137,300

164,100

26,800 (20%)

Psychologists

152,000

168,800

16,800 (11%)

Marriage and Family Therapists

27,300

31,300

3,900 (14%)

*Projected growth rate much higher than average for other professions. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Department of Labor, Occupational Outlook

Handbook 2010-11 http://bls.gov/oco/

The CEO of NAADAC addressed the issue of recruitment, retention and reimbursement in a

2006 commentary entitled Blueprint for the States: Policies to Improve the Way States Organize

and Deliver Alcohol and Drug Prevention Treatment (Tuohy, 2006). In this Blueprint, Tuohy

calls for increased understanding of addiction as a disease and increased attention to incentive

such as loan repayments and forgiveness, specifically for addictions counselors, as key

17

ingredients for success in recruitment. Tuohy also calls for adequate rewards as careers progress,

with promotions and recognition, as well as assistance for addictions counselors to remain up-to-

date on the latest advances in the addiction treatment and recovery field in order to retain a

highly qualified workforce. Finally, Tuohy recognizes the need for adequate compensation and

therefore higher rates of reimbursement for addictions professionals. Tuohy discusses the lack of

common national standards or competing standards for key professional areas, especially for

addictions professionals, while calling on multiple credentialing bodies to work together toward

core competencies that could be widely accepted.

As noted in the aforementioned demographic information, the majority of behavioral health

workers are white females in their mid-40s. In its publication, In the Nation’s Compelling

Interest: Ensuring Diversity in the Health-Care Workforce, the IOM (2004) reported that racial

and ethnic minority health care professionals are significantly more likely than their white peers

to serve minority and medically underserved communities, which would improve problems of

limited minority access to care. This report also cites studies that found that minority patients

who have a choice are more likely to select health care professionals of their own racial or ethnic

background, and that they are generally more satisfied with the care that they receive from

minority professionals.

There is also a significant mal-distribution of workers. As found by Greiner and Knebel (2003),

behavioral health professionals are in short supply in rural and low income communities. In fact,

55 percent of U.S. counties – all rural – do not have any practicing behavioral health workers.

And, as reported earlier, more than three-quarters of counties in the United States have a serious

shortage of mental health professionals (Thomas,et al.,2009). Data on the distribution of peers

working in either rural or urban areas are not available at this time. Though there is some

information about peer specialists, the information is limited in scope.

Data are available on a number of variables for the major disciplines comprising the workforce

providing services for persons with mental or substance use disorders. However, these data can

only be obtained from a variety of sources. No single source of workforce data, either discipline

specific or on a national level, exists that details the demographics, supply, demand or practice

information.

Special Issues of the Prevention Workforce

Particularly difficult issues confront the prevention workforce in behavioral health.

Underpinning some of these issues are different models of what constitutes prevention. In the

1950s, public health classified preventive measures in three basic categories, primary, secondary,

and tertiary. But in the 1980s, Dr. Robert Gordon proposed a new Operational Classification of

Disease Prevention (1983), which restricted “the use of the term ‘preventive’ to measures,

actions, or interventions that are practiced by or on persons who are not, at the time, suffering

from any discomfort or disability due to the disease or condition being prevented.” As

articulated by Gordon and reiterated by the Institute of Medicine in 2004 in the context of

behavioral health, these approaches may be for the whole population (universal prevention), for

selected sub-populations (selective prevention) or at-risk individuals (indicated) prevention. The

18

implementation of this model in behavioral health depends on a data-driven continuum of

evidence-based services.

The lack of a wide-spread understanding of the primary prevention model and the role of

prevention in behavioral health leads to a concomitant lack of priority given to funding

prevention activities which are evidence-based, well-documented, and known to be both

efficacious and cost-effective. The effect of this disparity is cumulative: low salaries force many

qualified individuals to leave the field; high staff turnover creates the need for additional

training; the cost of training can be prohibitive for programs and individuals.

An additional challenge for prevention professionals is the lack of a national standard for

credentialing. Despite the existence of the International Certification Reciprocity

Consortium/Alcohol and Other Drug Abuse which provides certification of competency for

prevention specialists, state and local programs may use their own certification standards or

impose no standards at all. This lack of standardization is compounded by the fact that states

vary significantly in their prevention approaches – some are bringing behavioral health and

primary care under one roof while others have substance abuse prevention programs within

public health or mental illness prevention integrated into specialty mental health services –

which further complicates the question of creating one national certification standard to apply

across the board.

Impact of Affordable Care Act and MHPAEA on the Behavioral Health Workforce

In 2014, up to 38 million more Americans will have an opportunity to be covered by health

insurance due to changes under the Affordable Care Act (Congressional Budget Office [CBO],

2010; SAMHSA, 2011). Between 20 to 30 percent of these people (as many as 11 million) may

have a serious mental illness or serious psychological distress, and/or a substance use disorder

(SAMHSA, 2011). Among the currently uninsured aged 22 to 64 with family income of less

than 150 percent of the federal poverty level, 36.8 percent had illicit drug or alcohol

dependence/abuse or mental illness (SAMHSA, 2011). However, the Supreme Court decision

on June 28, 2012 gave the states the option to expand Medicaid as stipulated in the Affordable

Care Act. The CBO therefore reduced by 6 million the number of people who may be covered

by Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CBO, 2012).

This growth in the number of people who will be identified with a mental or substance use

disorder requires an expanded workforce. However, the composition of the workforce will be

reshaped by the Affordable Care Act with the move toward more integrated primary and

behavioral health care. New integrated care structures such as accountable care organizations

and health homes funded or promoted by the Affordable Care Act offer new opportunities for

persons with behavioral health conditions, and will necessitate additional training for primary

care workers as well as new specialty practitioners as part of the multi-disciplinary teams. Brief

interventions and brief treatment will likely be delivered by staff in primary care settings as

screening for depression, alcohol and substance abuse becomes a standard part of care. Staff will

include health educators, nurse practitioners, care managers, physicians as well as counselors,

social workers, psychologists, and addiction specialists.

19

Primary care settings differ from the specialty sector. As integration of primary and behavioral

health services becomes the standard, there will be a greater emphasis on evidence-based

practices and outcomes, especially in light of the HHS National Quality Strategy and

SAMHSA’s National Behavioral Health Quality Framework which are focused on improving

quality of care as well as improving both administrative and clinical processes.

People with more severe and persistent mental and substance use disorders will receive longer

term and more intensive treatment, either within a primary care setting or specialty setting. The

use of peers to promote long-term recovery is also expanding across the country. These peer

specialists, who in some states are now being certified, play a key role in the recovery process

serving as role models, navigators, recovery coaches, as well as providing hope, a critical part of

the recovery process. These peer specialists are also an important addition to the workforce to

help meet the need for services and supports that can be provided by trained persons who are

certified but not licensed as traditional health or behavioral health care practitioners.

Creative retooling and repurposing of the existing behavioral health workforce will be required

to support integration, with some workers in significantly expanded and changed roles with

broader competencies. Great strides will need to be made in the adoption of evidence-based

practices, team work skills and collaboration. In primary care setting a team–based approach is

used which requires more flexibility in scheduling. New or expanded roles and types of workers

are also likely to be needed to facilitate integration, including health educators, behavioral health

specialists, and care managers (SAMHSA, 2011).

Enumeration of Needs

A number of challenges await the workforce over the next several years. As discussed above,

both the demand for services and where services are delivered will change in the coming years.

The rise in the use of medications for mental and substance use disorders as well as the

integration of care are reshaping who and how services are provided. The use of psychotropic

medications has grown exponentially over the past decade. Mojtabai and Olfson (2011) found

that antidepressants are the third most prescribed class of medications in the country. However,

often these patients are not clearly diagnosed or referred for further assessment as primary care

physicians are concerned about a diagnosis that could result in prejudice for the patient and lack

of easy access to mental health and addiction professionals. The use of medication assisted

addiction treatment is also increasing (SAMHSA, 2011).

Integrated care is predicated on a holistic, public health care model requiring a team approach to

primary and behavioral health services. Integrated care will bring additional challenges to the

field. Requirements for licensure/certification are not standardized across states and include

little, if any, preparation related to physical health conditions or working in primary care settings.

National core competencies for behavioral health care are lacking. Practice will be based on

science; employing evidence-based approaches will become the norm. However, the adoption of

evidenced-based practices still often has a lag time of about 15-20 years. The majority of

members of the core primary disciplines (physicians, nurses, social workers, psychologists,

physicians’ assistants and others) are also likely to have insufficient training in behavioral health.

20

In addition, the need for and adoption of interoperable electronic health records and other health

information technology is changing practice and increasing the accountability for quality. All of

these issues indicate successful integration of care will be predicated on comprehensive training

for all staff involved in providing services, whether in primary or specialty care settings and

whether in traditional or multi-disciplinary practices.

The prevalence of co-occurring mental and substance use disorders has been documented in the

2010 NSDUH. The findings indicate that 45.1 percent (9.2 million) of the 20.3 million adults

with substance use disorders also had a mental illness as compared to 17.6 percent without a

substance use disorder. Of the 45.9 million adults who had any mental illness, 20 percent or 9.2

million had a co-occurring substance use disorder. Comparatively, 11.2 million or 6.1 percent of

adults with a substance use disorder did not have a mental illness in the past year (SAMHSA,

2011). This underscores the need for the development and promotion of behavioral health

competencies among both the addictions and the mental health workforce.

As the use of medication assisted treatment increases and treatment for co-occurring disorders

becomes more frequent, employment of physicians in behavioral health settings may increase.

Physicians in primary care are also more likely to be prescribing such medications and treating

individuals with addictions. The use of physicians also increases the likelihood that primary care

will be delivered onsite in community mental health and substance abuse facilities. In a recent

study, almost 75 percent of the participating substance abuse treatment organizations indicated

that finding a physician in the local community who had experience treating substance use

disorders was somewhat or very difficult. More importantly, inadequate funding for physicians’

services was negatively associated with the employment of physicians (Knudsen et al., 2012).

Physicians report barriers to the use of medication assisted treatment and screening and brief

intervention, including not feeling comfortable in managing all components of either type of

intervention (Dilonardo, 2011).

Meeting the country’s behavioral health needs requires a sufficient supply of well trained,

competent workforce. Given the issues discussed in this paper there are some strategies that will

help us achieve the promise of better outcomes for people with and at risk for mental and

substance use disorders. These may include:

• Promoting cross training for the behavioral health workforce to enhance capabilities to

serve individuals with co-occurring disorders and how to work in complex multi-

disciplinary teams;

• Fostering the expansion of the workforce by recruiting a more diverse workforce and

concentrating on underserved populations. Specific populations that need additional

services include children and adolescents, geriatric patients, and those living in rural

areas. Increasing the use of consumers/persons in recovery, parent/family, and other

peers, as well as paraprofessionals and practitioner extenders;

• Disseminating and promoting the adoption of evidence-based practices to reduce the

delay in adoption of science-based interventions including ongoing supervision to ensure

treatment fidelity;

• Encouraging the development and dissemination of behavioral health core competencies

for the primary and other health care workforce;

21

• Providing training and education on recovery-oriented care and recovery principles for

the behavioral health field; and

• Developing standardized workforce data collection elements that can be collected and

analyzed on a regular basis to assist in gathering demographic, setting and practice

information.

SAMHSA and HRSA Workforce Initiatives

SAMHSA and HRSA each fund workforce initiatives that address many of the challenges facing

the behavioral health field. These initiatives provide a broad range of activities that address the

needs of the current workforce and provide support for future growth.

On June 5, 2012, SAMHSA and HRSA Administrators held a joint listening session with key

behavioral health field leaders. From that session, a consensus emerged about many issues that

need to be tackled if the behavioral health workforce is to keep pace with the growing need and

rapidly changing health care environment.

This portion of the report is divided into two sections. The first highlights SAMHSA’s and

HRSA’s current workforce programs and other activities to advance the behavioral health

workforce, and the second describes workforce collaborations between SAMHSA and HRSA,

including results from the joint listening session. Note that for programs spending only a portion

of their funds on workforce development activities. The FY 2012 funding levels provided are

approximate. Expenditures of FY 2012 funds may vary during project execution in order to be

responsive to emerging program needs (e.g., in a given year, a cohort of grantees may or may not

demonstrate a need for technical assistance on workforce development).

SAMHSA Workforce Programs

Addiction Technology Transfer Centers

The ATTC network, which was first funded in 1993, consisted of 14 regional centers and one

national coordinating center in the cohort that ended in FY 2011. They provide services in all 50

states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico and the Caribbean Basin, and the Pacific Islands.

The purpose of this program is to develop and strengthen the workforce that provides addiction

treatment services. The ATTCs partner with substance abuse Single State Authorities, treatment

provider associations, addiction counselors, multidisciplinary professionals, faith and recovery

community leaders, family members of those in recovery, and other stakeholders to: (1) raise

awareness of evidence-based and promising treatment and recovery practices; (2) build skills to

prepare the workforce to deliver state-of-the-art addiction treatment and recovery services; (3)

and change practice by incorporating these new skills into everyday use for the purpose of

improving addiction treatment and recovery outcomes. For the first time in its history, the

ATTC network has conducted a national workforce survey to obtain information on the state of

the current workforce.

This survey, Vital Signs: Taking the Pulse of the Addiction Treatment Profession (Ryan,

Murphy, & Krom, 2012), provides an overview of the characteristics and workforce

development needs of the substance use disorders treatment field.

22

The data collection process included a survey of clinical directors; telephone interviews with a

selected group of clinical directors; telephone interviews with thought leaders; and a review of

existing literature and data sets. The 57-item instrument survey was distributed by ATTC

Regional Centers to a sample of 631 programs drawn from the Inventory of Substance Abuse

Treatment Services using a dual sampling method to ensure that data would be both nationally

and regionally representative. The response rate was 88 percent.

A summary of the national findings about the substance abuse workforce as identified by the

ATTC survey is described below.

Basic demographics of the Substance Abuse workforce.

• Sixty-five percent of clinical directors had at least a master’s degree and they have, on

average, 17 years of experience in the field. Seventy-seven percent are state licensed or

certified. About one third are identified as being in recovery from a substance use

disorder.

• Thirty-six percent of direct care staff had a Master’s degree, and 24 percent had a

bachelor’s degree as their highest level of education. The majority of direct care staff is

currently licensed/certified or seeking licensure/certification. Slightly less than one-third

of direct care staff are in recovery from substance use disorders as estimated by their

clinical directors.

• Almost one-third of clinical directors are only somewhat proficient in web-based

technologies, and almost half of substance use disorder facilities do not have an

electronic health record system in place.

Common strategies and methodologies to prepare, retain, and maintain the Substance Abuse

workforce.

• Substance use disorder treatment facilities most commonly offer professional

development for staff through new employee orientation, ongoing training, and direct

supervision. When facilities do not provide for staff training and continuing education,

the most commonly reported reason was a lack of funds.

• The majority of survey respondents reported that staff at their facility had been trained in

both culturally responsive and gender responsive substance use disorder treatment.

• Clinical directors interviewed emphasized the positive effects that developing

relationships with colleges and universities can have on recruiting qualified professionals.

In order to achieve the major goals, the ATTCs utilize technology transfer as a systematic

process through which skills, techniques, models and approaches emanating from research are

translated, disseminated and adopted by practitioners. They also develop curricula standards for

pre-service and academic programs which are compatible with and support SAMHSA’s

Addiction Counseling Competencies (CSAT, 2006; 2007) and provide a coordinated approach to

the training and technology transfer needs of clinical supervisors. ATTCs develop and

disseminate educational materials and resources on substance use treatment. They also

collaborate on developing and supporting emerging leaders in the field.

23

Another critical component of technology transfer is to reduce the time it takes for evidence-

based practices to be adopted by practitioners. Toward that end, SAMHSA and the National

Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) have an inter-agency agreement (IAA) to facilitate cooperative

effort that foster the timely transfer and implementation of research-based findings from NIDA-

conducted research, including NIDA's Clinical Trials Network. Through this IAA, NIDA

transfers $1.5 million each year to SAMHSA for the ATTCs to support the NIDA/SAMHSA

Blending Initiative. Begun in 2001, this project is designed to meld science and practice together

to improve substance use disorder treatment and accelerate the dissemination of research-based

drug abuse treatment findings into community-based practice.

There are three components to the Blending Initiative:

• Blending Conferences – Each is designed to enhance bidirectional communication

between researchers, clinical practitioners, and policy-makers regarding innovative

scientific findings about drug abuse and addiction.

• State Agency Partnerships – NIDA works closely with federal and state policy-makers to

help identify strategies to accelerate the adoption of science-based practices.

• Development of Products and Tools – Blending Teams composed of members from the

ATTC Network, NIDA researchers, and community treatment providers participating in

NIDA's Clinical Trials Network, are convened to design user-friendly tools or “products”

that are based on recently tested NIDA research.

These products are introduced to treatment providers to facilitate the adoption of science-based

interventions in their communities at nearly the same time that research results are published in

peer-reviewed journals.

The ATTC Network touches many people working in the addiction services field, which is

attested to by the following data taken from 2010:

• ATTC Network listserv has over 57,000 subscribers.

• There were 987 events with 26,655 participants.

• One hundred eighty-five products accessible on the ATTC Network Websites received

19,940 downloads.

• The ATTC Web site had almost a million (979,680) unique visits and many people

visited more than once as there were 2,612,592 total views.

The ATTC program was re-competed in 2012 with 10 geographic ATTCs reflecting the 10 HHS