Analyses of the

European air

transport market

Annual Report 2007

EUROPEAN

COMMISSION

EU_ENTWURF_08:00_ENTWURF_01 01.04.2026 13:07 Uhr Seite 1

UPDATED VERSION

EU_ENTWURF_08:00_ENTWURF_01 01.04.2026 13:07 Uhr Seite 2

Air Transport and

Airport Research

Annual Report 2007 2008-12-02

Release: 2.2 Page 1

Annual analyses of the European air

transport market

Annual Report 2007

German Aerospace Center

Deutsches Zentrum

für Luft- und Raumfahrt e.V.

in the Helmholtz-Association

German Aerospace

Center

Air Transport and Airport Research

Linder Hoehe

51147 Cologne

Germany

Head: Prof. Dr. Johannes Reichmuth

Authors: Erik Grunewald, Amir Ayazkhani, Dr. Peter Berster,

Gregor Bischoff, Prof. Dr. Hansjochen Ehmer, Dr. Marc

Gelhausen, Wolfgang Grimme, Michael Hepting, Hermann

Keimel, Petra Kokus, Dr. Peter Meincke, Holger Pabst, Dr. Janina

Scheelhaase

December 2008

web: http://www.dlr.de/fw

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

2008-12-02 Annual Report 2007

Page 2 Release: 2.2

Document Control Information

Responsible project manager: DG Energy and Transport

Project task: Annual analyses of the European air transport market 2007

EC contract number: TREN/05/MD/S07.74176

Release: 2.2

Save date: 2008-12-02

Total pages: 222

Change Log

Release Date Changed Pages or Chapters Comments

1.2 2008-06-20 Final Report

2.0 2008-10-10 chapters 1,2,3 Final Report - full year 2007 draft

2.1 2008-11-20 chapters 1,2,3,5 Final updated Report

2.2 2008-12-02 all Layout items

Disclaimer and copyright:

This report has been carried out for the Directorate-General for Energy and Transport in the

European Commission and expresses the opinion of the organisation undertaking the contract

TREN/05/MD/S07.74176. These views have not been adopted or in any way approved by the

European Commission and should not be relied upon as a statement of the European

Commission's or the Transport and Energy DG's views. The European Commission does not

guarantee the accuracy of the information given in the report, nor does it accept responsibility

for any use made thereof.

Copyright in this report is held by the European Communities. Persons wishing to use the

contents of this report (in whole or in part) for purposes other than their personal use are invited

to submit a written request to the following address:

European Commission - DG Energy and Transport - Library (DM28, 0/36) - B-1049 Brussels

e-mail (

http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/energy_transport/contact/index_en.htm)

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

Annual Report 2007 2008-12-02

Release: 2.2 Page 3

Content

2007 in brief…………………………..……………………………………….……………………….7

1

Air Traffic .......................................................................................................................15

1.1 Global Passenger and Freight Volume ........................................................................15

1.1.1 Global Passenger Volume .................................................................................15

1.1.2 Passenger Traffic Flows between the World Regions .........................................17

1.1.3 Global Freight Volume......................................................................................18

1.1.4 Freight Traffic Flows between the World Regions..............................................20

1.1.5 Comparison of Passenger and Freight Volume of Europe and the other

World Regions..................................................................................................

21

1.2 Air Traffic in EU-27 ....................................................................................................22

1.2.1 European Passenger Traffic...............................................................................22

1.2.2 Passenger Traffic Flows between EU Member States .........................................22

1.2.3 Passenger Traffic Flows between the EU-27 and other World Regions...............23

1.2.4 European Air Freight Traffic Volume .................................................................24

1.2.5 Freight Traffic Flows between EU-27 Member States ........................................25

1.2.6 Freight Traffic Flows between the EU-27 and other World Regions ...................26

1.3 Air Traffic in EU Member States .................................................................................28

1.3.1 Passenger Volume ............................................................................................28

1.3.2 Freight volume .................................................................................................29

1.3.3 Flight Volumes in EU Member States ................................................................31

1.4 Flight Efficiency..........................................................................................................33

1.5 General Aviation........................................................................................................33

2 Airlines...........................................................................................................................41

2.1 Passenger Airlines ......................................................................................................41

2.1.1 Supply by Airline Type ......................................................................................44

2.1.2 Air Transport Demand ......................................................................................52

2.1.3 Passenger Fleet.................................................................................................65

2.1.4 Airline Financial Performance............................................................................70

2.1.5 Alliances...........................................................................................................77

2.1.6 Competition .....................................................................................................85

2.1.7 Public Service Obligations – PSO .......................................................................90

2.1.8 Fare Development ............................................................................................91

2.2 Cargo Airlines............................................................................................................95

2.2.1 Cargo Airlines – Supply.....................................................................................96

2.2.2 Cargo Airlines – Demand................................................................................100

2.2.3 Cargo Airlines - Fleet ......................................................................................105

2.2.4 Cargo Airlines - Financial Performance............................................................107

2.2.5 Cargo Airlines - Alliances ................................................................................108

2.2.6 Cargo Airlines - Competition ..........................................................................112

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

2008-12-02 Annual Report 2007

Page 4 Release: 2.2

3

Airports........................................................................................................................115

3.1 Passengers...............................................................................................................115

3.2 Aircraft Movements .................................................................................................117

3.3 Freight.....................................................................................................................120

3.4 Ground Handling.....................................................................................................122

4 Air Transport Forecasts .................................................................................................126

4.1 Global Forecasts ......................................................................................................126

4.2 European Forecasts..................................................................................................128

4.2.1 Eurocontrol Short-Term Forecast September 2007 ..........................................129

4.2.2 Eurocontrol Medium-Term Forecast 2007-2013..............................................130

4.2.3 Eurocontrol Long-Term Forecast 2006-2025 ...................................................131

5 Regulatory Developments.............................................................................................132

5.1 International Aviation ..............................................................................................132

5.1.1 Horizontal Agreements...................................................................................133

5.1.2 Bilateral Agreements ......................................................................................134

5.1.3 Common Aviation Area with the EU’s Neighbours ..........................................134

5.1.4 Global Agreements.........................................................................................136

5.1.5 International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) ..............................................139

5.2 Internal market ........................................................................................................140

5.3 Competition ............................................................................................................140

5.3.1 State Aid ........................................................................................................140

5.3.2 Infringements .................................................................................................141

5.3.3 Merger ...........................................................................................................142

5.4 Distribution Networks (CRS).....................................................................................142

5.5 Consumer Protection ...............................................................................................144

5.5.1 Passenger Rights in the European Union .........................................................144

5.5.2 Persons with Reduced Mobility .......................................................................144

5.5.3 Misleading Airline Ticket Websites ..................................................................145

5.6 Air Traffic Management...........................................................................................145

5.6.1 Single European Sky (SES)...............................................................................146

5.6.2 Functional Airspace Blocks (FABs) ...................................................................147

5.6.3 SESAR ............................................................................................................147

5.7 Airports ...................................................................................................................149

5.7.1 “Airport Package”..........................................................................................149

5.7.2 Slots...............................................................................................................152

5.8 Safety ......................................................................................................................153

5.9 Investigation of Civil Aviation Accidents, Incidents and Occurrence Reporting ..........153

5.10 Insurance.................................................................................................................154

6 Environmental development .........................................................................................155

6.1 The Year in Brief ......................................................................................................155

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

Annual Report 2007 2008-12-02

Release: 2.2 Page 5

6.2

Emissions Trading Scheme for Aviation ....................................................................157

6.3 Aviation Noise .........................................................................................................159

7 Consumer Issues ..........................................................................................................162

7.1 Punctuality...............................................................................................................162

7.1.1 Actual Punctuality...........................................................................................162

7.1.2 ATFM Delays ..................................................................................................167

7.2 Delayed Baggage.....................................................................................................169

7.3 AEA Flight Regularity ...............................................................................................170

7.4 Air Passenger Rights in the European Union.............................................................172

7.4.1 Implementation of Air Passenger Rights..........................................................174

7.4.2 European Consumer Centre Network .............................................................177

7.5 Hidden Charges.......................................................................................................179

7.6 Refund of Taxes, Fees and Charges..........................................................................179

7.7 Persons with Reduced Mobility: Regulation (EC) 1107/2006 .....................................180

7.8 Cabin Seating ..........................................................................................................180

8 Aircraft and Engine Manufacturers ...............................................................................182

8.1 Highlights of 2007...................................................................................................182

8.2 Aircraft Market Overview.........................................................................................183

8.2.1 Aircraft Orders Overview ................................................................................183

8.2.2 Aircraft Orders by Market Segments, Manufacturers and Types ......................185

8.2.3 Aircraft Deliveries by Market Segments, Manufacturers and Types ..................191

8.3 Engine Market Overview..........................................................................................197

9 Employment in European Air Transport.........................................................................200

9.1 Basic Concepts and Definitions of the EU Labour Force Survey .................................200

9.2 Definition of Air Transport in the Scope of National Accounts ..................................200

9.3 Employment Trends in European Air Transport.........................................................201

9.4 Coherence with other Employment Estimates ..........................................................203

10 Safety...........................................................................................................................205

10.1 Air Transport Safety .................................................................................................205

10.2 Notable Events......................................................................................................... 205

10.3 Safety Performance..................................................................................................206

10.4 List of Airlines Banned within the EU........................................................................210

10.5 EU-OPS (EU Operations)...........................................................................................211

10.6 The European Community SAFA Programme ...........................................................211

10.7 The European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA)...........................................................212

11 Annex ..........................................................................................................................215

11.1 Abbreviations ..........................................................................................................215

11.2 Geographical Coverage Information.........................................................................217

11.3 List of figures...........................................................................................................218

11.4 List of tables ............................................................................................................221

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

2008-12-02 Annual Report 2007

Page 6 Release: 2.2

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

Annual Report 2007 2008-12-02

Release: 2.2 Page 7

2007 in brief

Traffic

In 2007 the worldwide passenger volume grew according to ICAO data from approximately

2,128 million to more than 2,260 million. This corresponds to a growth of approximately 6.2%.

During the same period the number of passenger kilometres grew slightly more than the

passenger volume from 3,941 billion passenger kilometres to approximately 4,201 billion

passenger kilometres. This corresponds to a growth of 6.6%.

The ICAO data also states that 41.6 million tonnes of freight were globally transported by air in

2007. This represents an increase in freight traffic volume of 4.5% compared to the previous

year’s result. The global tonne-kilometres rose in the same period from 149.7 to 158.4 billion,

which corresponds to an increase of 5.8%.

According to EUROSTAT, a total of 792 million passengers were transported by means of air

transport in the 27 EU member states (EU-27) in 2007. Compared to 2006, this corresponds to a

growth of approx. 7.2%. For intercontinental traffic, the relation between the EU and North

America was by far the most important one with approximately 60.1 million passengers in 2007.

In the EU-27, a total of approx. 12.6 million tonnes of freight and mail were loaded and

unloaded in 2007. Compared to the large extra-EU freight flows (9.9 million tonnes), the

quantity of freight carried between the individual EU member states is rather low, being only 2

million tonnes. The main linkage with regard to air freight/mail transport is seen between

Europe and North America. In 2007 more than 1.4 million tonnes were carried to North America

(a decline of 0.3%), and 1.3 million tonnes to Europe (7.1% growth).

With regard to the development of passenger traffic in the individual EU member states, an

increase in passenger traffic is revealed in all countries in the time frame of 2006 to 2007. The

growth in the new member states was above the average of EU growth in general.

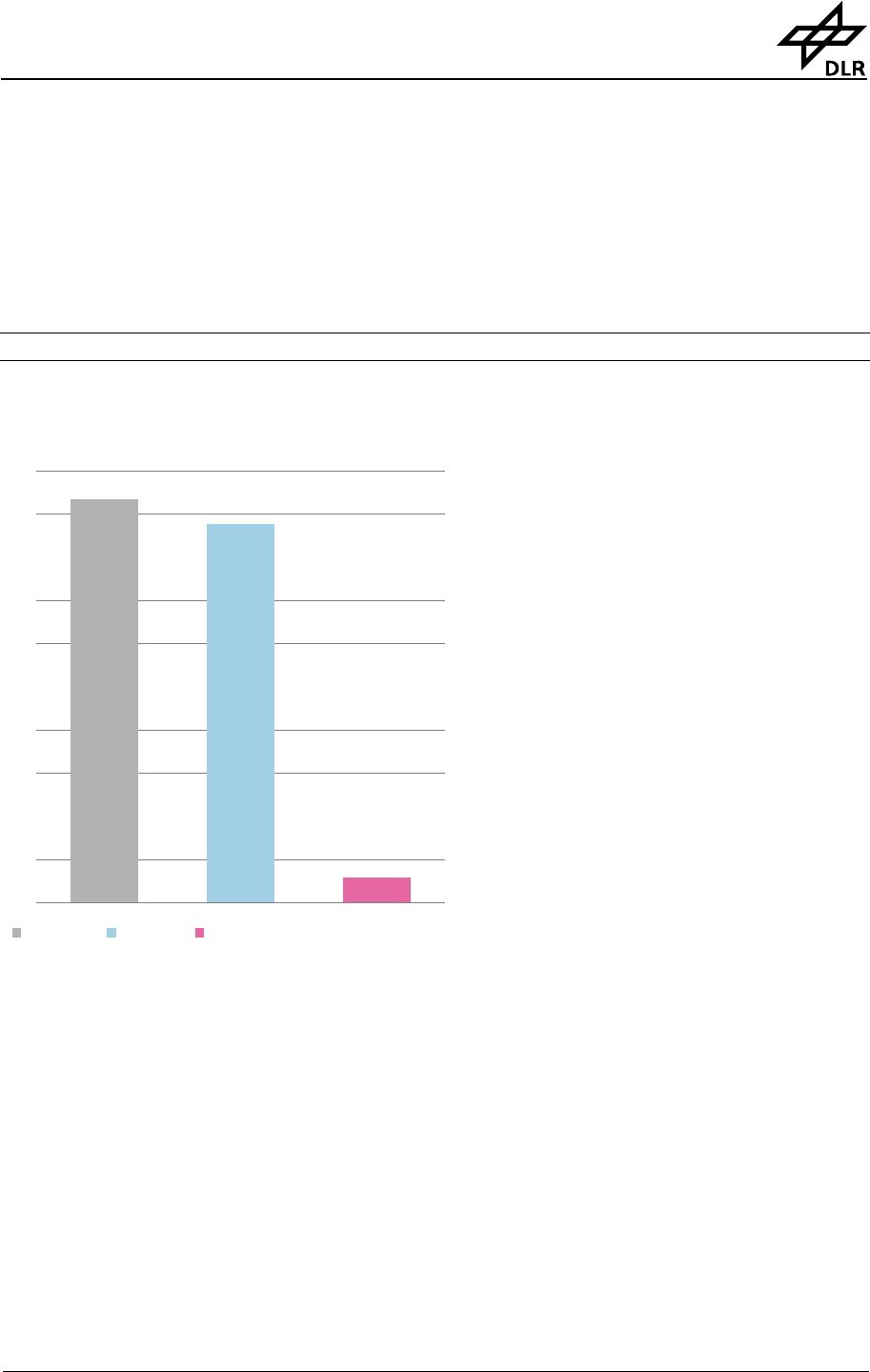

Air traffic in Europe showed an increase of a good 5% in 2007

Source: Eurocontrol

Approximately 9.7 million flights were recorded in the so-

called Eurocontrol Area 1999 in 2007, with approximately

one million respective arrivals and departures which

crossed the border of the Eurocontrol district, 7.6 million

domestic flights within the Eurocontrol district and about

0.1 million flights which crossed the Eurocontrol district.

Compared to 2006, flight movement traffic increased by

about 5.1%.

9,682,139

9,211,495

2006 2007

Departures, arrivals,

internals and overflights

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

2008-12-02 Annual Report 2007

Page 8 Release: 2.2

Airlines

European air services play an important role in worldwide air transportation. Taking one week in

July 2007 as a reference for the summer period, 19% of the 582,000 movements originate in

one of the 27 EU member states; taking all 46 European countries into consideration, the global

share increases to 22.5%. Europe has about 146,000 intraregional flights at this time, whereas

nine thousand are on the North Atlantic, and nine thousand to Asia, both being the most

important interregional services worldwide. The most important route by far is Madrid –

Barcelona with a frequency of 486 flights per week per direction. The top international service is

Amsterdam – London Heathrow with 173 weekly take-offs per direction. The busiest

intercontinental air route is London – New York with 130 one way services per week. However,

the average number of seats on this route is, with 292 seats, far higher than on Barcelona –

Madrid with 157 seats.

Lufthansa German Airlines was the biggest carrier in terms of the number of flights, but it has

now been left far behind by Air France – KLM following the take-over. But these two airlines still

operate independently on the market. The average seat capacity of the top 25 airlines is 127 per

flight. The average seat capacity of the LCCs is, with 149 seats, somewhat higher.

Concentrating on the top 25 carriers per business model, the market share of the LCCs increases

to roughly one third. Within the LCCs, there is a somewhat higher concentration effect on the

top 2 carriers Ryanair and easyJet. Also, for regional airlines, the 2 biggest carriers Wideroe’s and

Binter Canarias are outstanding. The average seat capacity for these airlines is only 59 seats per

flight due to the high proportion of short haul regional aircraft. The concentration effect of the

holiday carriers on the top level is not as obvious as for the other business models; their average

seat capacity is, with 190 seats, higher than all the other models.

Worldwide there are more than 600 airline cooperation agreements, mainly code-sharing

partnerships, but only three global strategic alliances: Star Alliance, SkyTeam and oneworld.

With their networks, they try to cover at least the most important global traffic flows. The

number of members of these alliances is still increasing though there are also some airlines

withdrawing. In most cases, alliance member airlines apply the FSNC

1

business model. Some

FSNCs, especially in the Middle East, are not (yet) members of strategic alliances. In some cases

however, they cooperate with alliance members by means of code-sharing.

Of the worldwide 50 biggest FSNCs in terms of passenger numbers, 17 are based in Europe, 9

are US-American and 20 airlines are from the Asia-Pacific region. The North American airlines

have a 27% market share in terms of carried passengers, compared to the European airlines

with 27%. But this number shows the concentration and the size of the American carriers

compared to their European counterparts. The average flight distance in North America is 2300

1

Full Service Network Carriers

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

Annual Report 2007 2008-12-02

Release: 2.2 Page 9

km, 100 km less than in the rest of the world. The flight distance in Europe is, with 2270 km,

even shorter than in North America.

Airports

The top 20 airports worldwide account for 24% of the passengers handled worldwide. The two

busiest airports are Hartsfield-Jackson in Atlanta and O’Hare International in Chicago. The top

20 airports comprise of ten airports located in the USA, five in Europe and five in Asia. The

biggest European airport is London Heathrow in third place while the biggest Asian airport is

Tokyo International (Haneda) in fourth place. The top 20 European airports account for 14% of

the passengers handled worldwide, whereas 45% of the passengers in Europe choose one of

the top 20 airports in Europe. The top three places are occupied by London Heathrow, Paris

Charles de Gaulle and Frankfurt/Main, which also represent major hub airports in Europe with a

high share of intercontinental travel. In 2007, total number of passengers increased by 5.6%

worldwide compared to 2006.

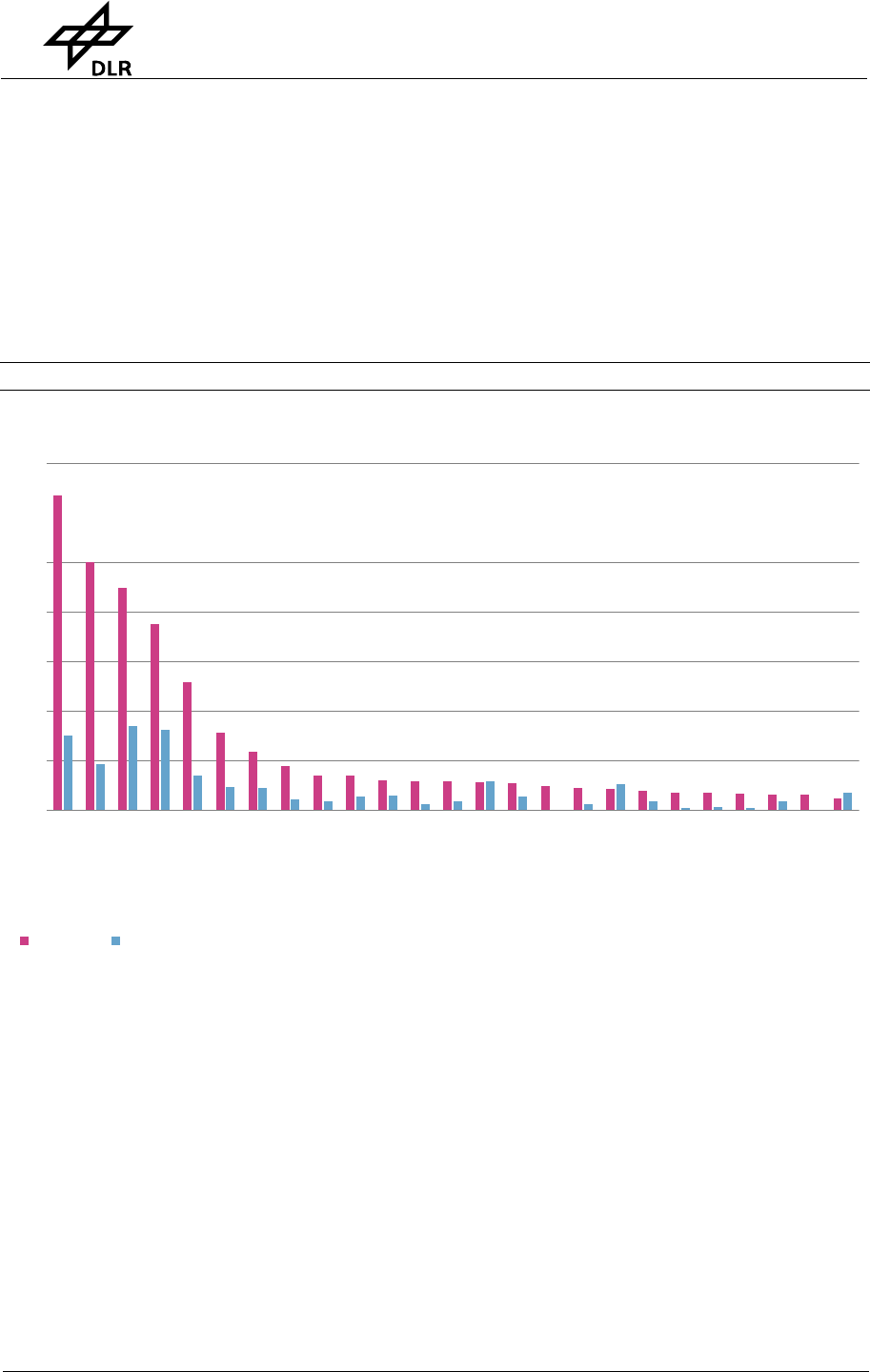

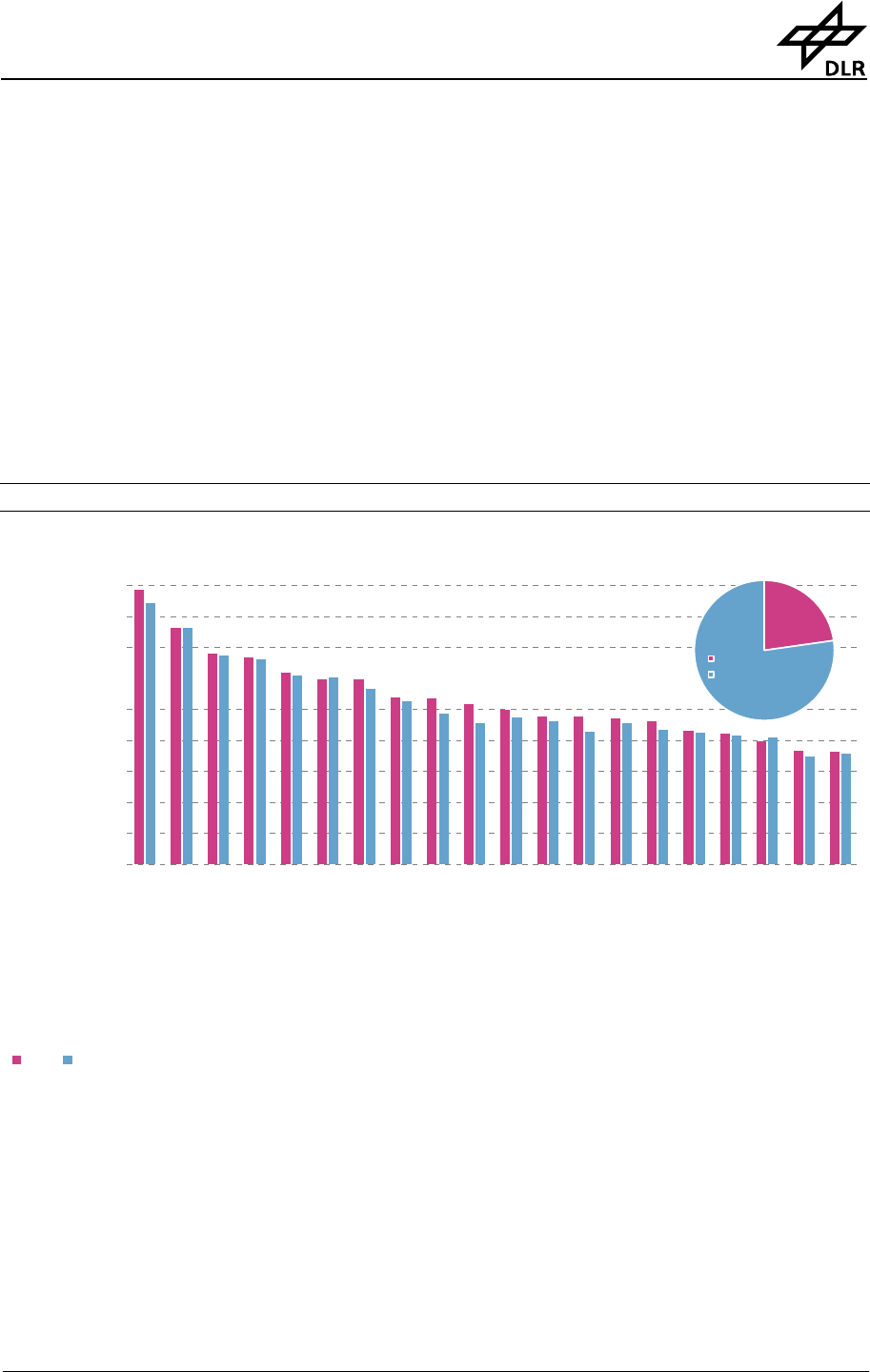

Annual growth of the 20 biggest airports in terms of commercial air passengers worldwide

Source: ACI 2008

ranking regarding total numbers in 2007

3.8%

13.9%

2.6%

5.4%

0.8%

-5%

0%

5%

10%

15%

ATLANTA(ATL)

CHICAGO (ORD)

LONDON (LHR)

TOKYO (HND)

LOS ANGELES(LAX)

PARIS (CDG)

DALLAS (DFW)

FRANKFURT (FRA)

BEIJING (PEK)

MADRID (MAD)

DENVER (DEN)

AMSTERDAM (AMS)

NEW YORK (JFK)

HONG KONG (HKG)

LAS VEGAS (LAS)

HOUSTON (IAH)

PHOENIX (PHX)

BANGKOK (BKK)

SINGAPORE (SIN)

ORLANDO (MCO)

Relative change in the

Number of Passengers

2007 vs. 2006

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

2008-12-02 Annual Report 2007

Page 10 Release: 2.2

Annual growth of the 20 biggest airports in terms of flight movements worldwide

Source: ACI 2008

ranking regarding total numbers in 2007

5.0%

3.2%

0.9%

11.1%

0.7%

2.1%

-5%

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

ATLANTA (ATL)

CHICAGO (ORD)

DALLAS (DFW)

LOS ANGELES (LAX)

DENVER (DEN)

LAS VEGAS (LAS)

HOUSTON (IAH)

PARIS (CDG)

PHOENIX (PHX)

CHARLOTTE (CLT)

PHILADELPHIA (PHL)

FRANKFURT (FRA)

MADRID (MAD)

LONDON (LHR)

DETROIT (DTW)

AMSTERDAM (AMS)

MINNEAPOLIS (MSP)

NEW YORK (JFK)

NEWARK (EWR)

MUNICH (MUC)

Relative change in the

Number of Movements

2007 vs. 2006

The top 20 airports in terms of commercial aircraft movements are located exclusively in the USA

or Europe. The biggest airport is again Hartsfield-Jackson in Atlanta, closely followed by O’Hare

International in Chicago. However, the difference in the number of commercial aircraft

movements in relation to the subsequent airports is more distinct compared to the situation

reflecting the above-described passenger numbers. This is partly due to the larger utilisation of

smaller aircraft for domestic air travel at US airports. The top 20 airports account for 21% of the

worldwide commercial aircraft movements, against the 12% of the worldwide aircraft

movements that take place at the top 20 European airports. Their share increases to 38% when

only aircraft movements at European airports are taken into account. The top 3 European

airports are Paris Charles de Gaulle, Frankfurt/Main and Madrid. London Stansted is the major

low cost carrier airport in Europe, having both the largest number of low cost operations and

the highest share of low cost flights in relation to the total number of take-offs.

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

Annual Report 2007 2008-12-02

Release: 2.2 Page 11

Annual growth of the 20 biggest airports in terms of commercial air freight worldwide

Source: ACI 2008

ranking regarding total numbers in 2007; ANC data includes transit freight

3.9%

5.4%

8.4%

7.9%

-10%

-5%

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

MEMPHIS (MEM)

HONG KONG (HKG)

ANCHORAGE (ANC)

SHANGHAI (PVG)

INCHEON (ICN)

PARIS (CDG)

TOKYO (NRT)

FRANKFURT (FRA)

LOUISVILLE (SDF)

MIAMI (MIA)

SINGAPORE (SIN)

LOS ANGELES (LAX)

DUBAI (DXB)

AMSTERDAM (AMS)

NEW YORK (JFK)

TAIPEI (TPE)

CHICAGO (ORD)

LONDON (LHR)

BANGKOK (BKK)

BEIJING (PEK)

Relative change in

loaded and unloaded

freight and mail in

metric tonnes

2007 vs. 2006

In 2007, total air freight increased by 3.0% compared to 2006. The largest 20 airports in terms

of freight handled 48% of the total air freight worldwide. The three biggest freight airports are

Memphis (USA), Hong Kong (China) and Anchorage in Alaska, USA. The biggest European

freight airport is Paris in sixth place. However, the top 20 European airports account for 15% of

the total freight handled worldwide, while most of the freight is handled at US or Asian airports.

Freight operations in Europe are concentrated on only a few airports: 80% of the total air

freight is handled at the top 20 airports.

Forecasts

Air transport forecasts published in 2007 by Boeing, JADC, Bombardier and Embraer assume an

average worldwide GDP-growth rate between 3.0 and 3.2%. According to the outcome of the

global air transport demand forecast, yearly average growth rates between 4.7 and 5.0% for

passenger traffic and approx. 6% for freight traffic are indicated in the time horizon until 2026.

In the current Airbus Market Forecast, which was published at the beginning of 2008,

worldwide air traffic is forecasted to grow by approximately 4.9% until the year 2026. If we

take the number of 3,720 billion revenue passenger kilometres (RPK) from ICAO in 2005 as a

basis, this yearly growth will lead to approximately 10 billion RPK in 2025.

Eurocontrol published a short-term and a medium-term forecast in 2007. From 2007 to 2008, a

growth of 5.5% is expected for IFR movements, allowing a forecast margin of 4.4 to 5.5%. The

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

2008-12-02 Annual Report 2007

Page 12 Release: 2.2

expected growth considerably differs regionally, as already experienced in the past. In the

medium-term forecast, three scenarios were presented: Eurocontrol assume for the forecast

period from 2007 to 2013 an average annual growth in flight movements of 3.4% in the

Baseline-Scenario, 4.2% in the High and 2.6% in the Low-Scenario. In the forecast-year 2013,

these growth rates would lead to 11.3 million IFR movements in the Low, 11.9 million in the

Baseline, and 12.6 million IFR movements in the High-Scenario.

Regulatory

Regulatory issues and legislative developments in the year 2007 will be described in chapter 5.

While some aspects are mentioned in the other specific chapters concerning these topics (air

passenger rights as a consumer issue, environment, safety), this part of the annual analyses of

the European air transport market points out the work and cooperation between the European

Commission, the Council and the European Parliament as the decisive institutions for European

legislation.

Starting with the Community and its external competence besides the Member States and

therefore as a new player in the international and globalising field of civil aviation, the view is

focused on the internal Common Market and airline competition. The Community has

influenced many developments concerning consumer protection and environmental issues.

These topics play a major role in air transport, too. Air traffic management (ATM) as a technical

part of the air transport market is about to integrate in Europe and raise many questions in its

requirements and implementations. At the same time, the infrastructure on the ground has to

keep step with the developments to ensure, besides all other sectors, a safe and efficient

performance of international civil aviation. At the end, investigation of civil aviation accidents is

briefly mentioned.

Environmental

The European Commission aims to improve the quality of the environment by reducing the

growing climate change impact of international aviation. Therefore, international aviation will be

included in the already existing EU Emissions Trading Scheme for the limitation of CO

2

emissions

by the year 2012. On December 20th, 2007, the EU Environmental Council reached a political

agreement on a draft directive on this issue. The publication of a modified legislative proposal

on this basis is expected for spring 2008.

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

Annual Report 2007 2008-12-02

Release: 2.2 Page 13

Consumer Issues

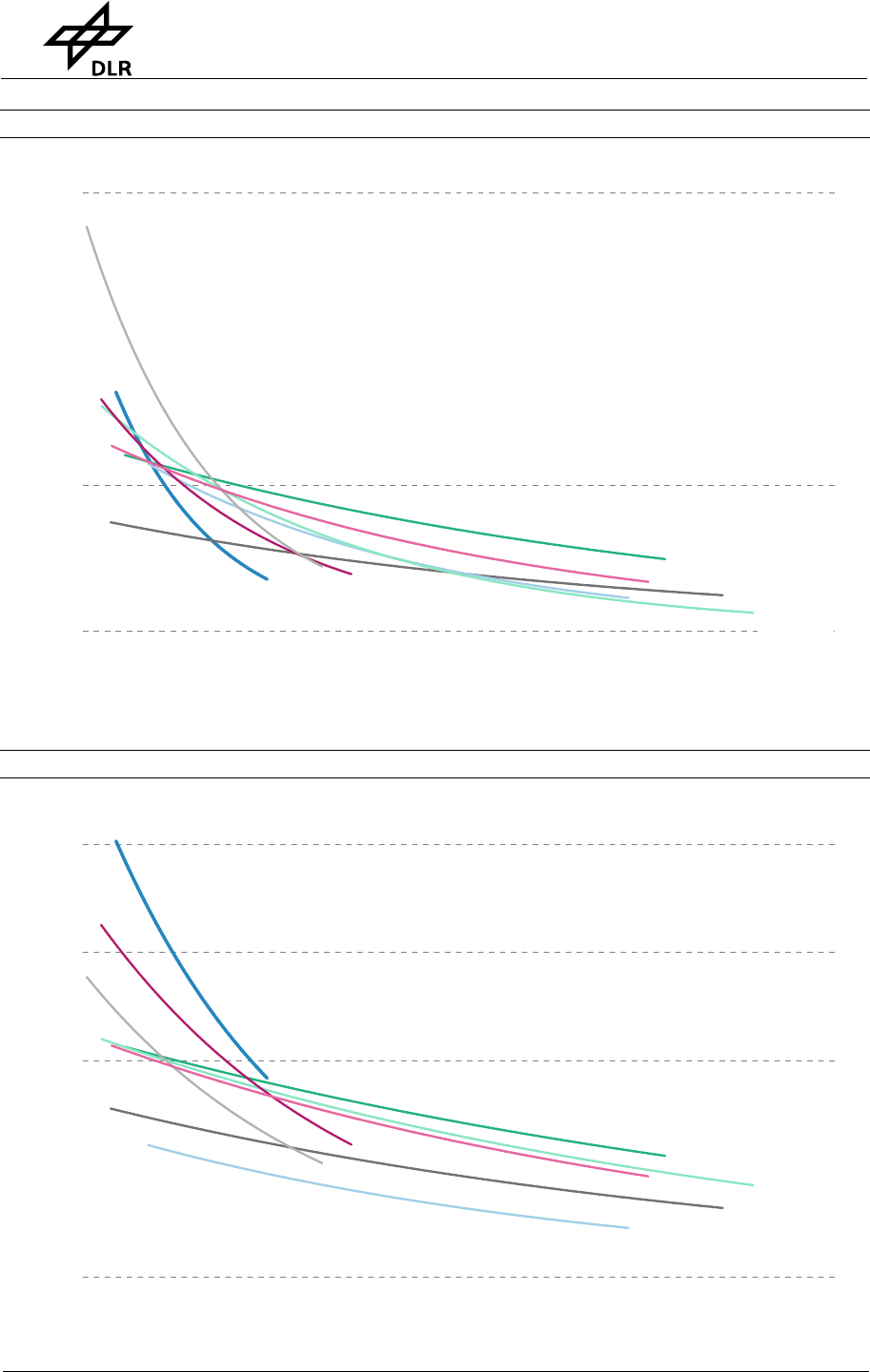

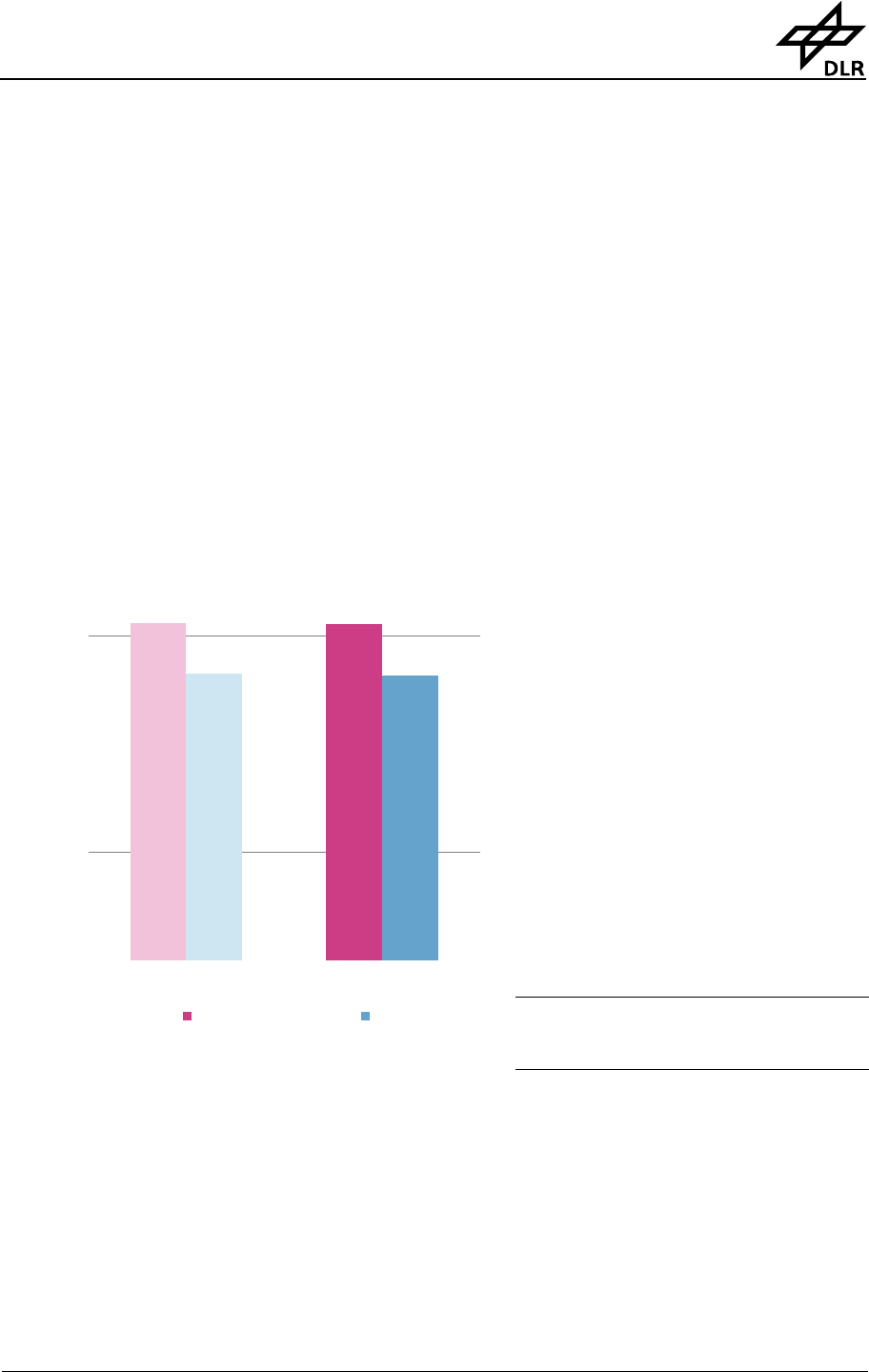

In 2007, the consumer-relevant key performance parameters punctuality and baggage delivery

deteriorated in comparison with results for 2006.

Punctuality slightly decreased; baggage delivery slightly worsened

Source: AEA

Intra-European Departure Punctuality

79.4%

78.9%

20.6%

21.1%

2006

2007

on time delayed (>15 minutes)

Appraising the published results of the Association of European Airlines (AEA) for its members,

departure punctuality on intra-European services declined to 78.9% compared with 79.4% in

2006. On the arrival level, 77.7% of intra-European services met their schedules with no more

than 15 minutes delay, which is nearly the same result as in 2006 (77.9%).

The number of bags delayed per 1000 passengers carried by AEA-airlines was 16.6, thus slightly

inferior to the previous year’s situation with 15.7 bags delayed per 1000 boarded persons. As

per AEA, most of the change for the worse arose in the second quarter of 2007 due to

problems with transfer baggage systems at several European airports, a situation occurring in

December again.

15.7

16.6

2006 2007

delayed bags per 1,000 passengers enplaned

15.7

16.6

2006 2007

delayed bags per 1,000 passengers enplaned

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

2008-12-02 Annual Report 2007

Page 14 Release: 2.2

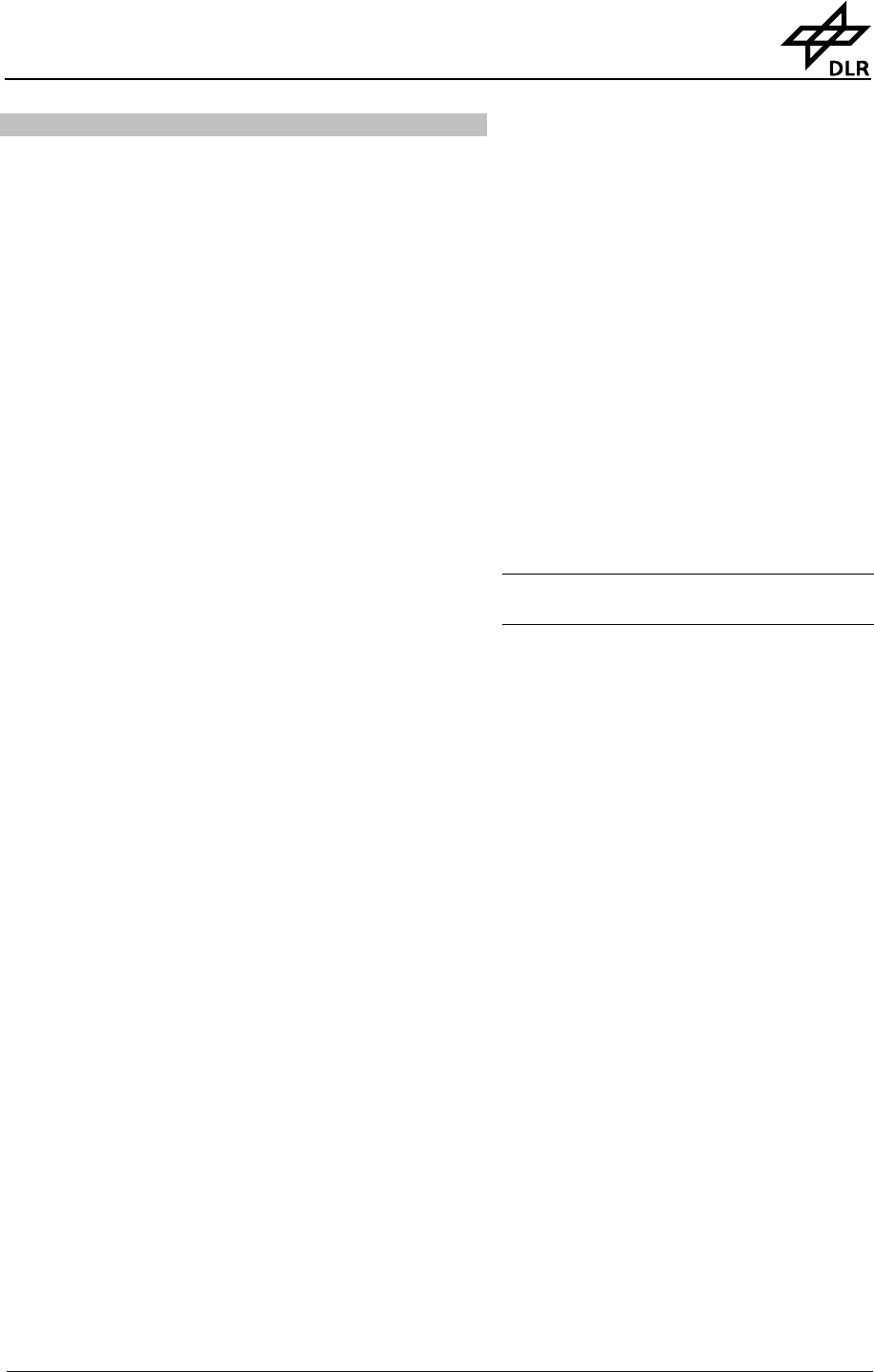

Manufacturers

Orders of Passenger and Cargo Aircraft (commercial operators

only)

Source: Ascend

The number of orders for passenger and cargo aircraft by

commercial operators saw a strong increase in 2007

compared to 2006. More than 3700 aircraft were ordered

in 2007, almost 50% more than in 2006. The number of

aircraft delivered saw a considerable increase in 2007. With

almost 1200 deliveries of commercial passenger and cargo

aircraft, this marks an increase of almost 12 per cent

compared to the previous year. The world fleet of

passenger aircraft in commercial operation with more than

20 seats has increased by more than 5 per cent in 2007

compared to the

preceding year. By the end of 2007, almost 20,000

passenger aircraft were in use at airlines and other

commercial operators.

Deliveries of Passenger and Cargo Aircraft (commercial

operators only)

Source: Ascend

1059

1184

2006 2007

+ 11.8%

2508

3743

2006 2007

+ 49.2%

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

Annual Report 2007 2008-12-02

Release: 2.2 Page 15

1 Air Traffic

1.1 Global Passenger and Freight Volume

Information on the development of worldwide air traffic is available in the form of traffic

statistics published by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO). The basis for these

statistics are reports from ICAO member states on the air traffic activity of airlines based in their

territory. However, some of the data published by ICAO has to be estimated, since not all of the

190 ICAO member states participate in the survey. The most significant trends are nonetheless

considered to be correctly represented, since the major states in terms of air traffic, such as the

USA and the Member States of the EU, regularly report to the ICAO on the traffic levels

achieved by their airlines.

The ICAO distinguishes between international and national traffic. The combination of both

figures is the total traffic. The essential information for the allocation of a flight to the

appropriate category is the airline’s country of origin and the location of the originating and

destination airports. According to ICAO rules, a flight is classified as international if either the

airport of origin or destination (or both) is located outside the territory of the airlines’ home

country. Thus, cabotage (the transportation of passengers or goods within a country) by a

foreign airline is considered as international air traffic. Conversely, a flight by a French airline

from Paris to one of France's overseas territories, for example, is considered to be a domestic

flight, since the originating and destination airports are both located in the territory of the

airline’s home country. The ICAO also makes a distinction between scheduled and non-

scheduled airlines. According to the ICAO, scheduled airlines are the predominant means of

transportation. The following discussion only relates to flights performed by scheduled airlines.

1.1.1 Global Passenger Volume

For passenger transport, the ICAO records the number of passengers carried and the number of

passenger kilometres. Please note, however, that the latter measure only relates to the number

of seat kilometres sold. Figure 1-1 shows the development of air traffic levels for both domestic

and international scheduled airline traffic. Passengers are counted for each flight, with each

flight identified by its flight number. Passengers who change flight during their journey are

therefore counted multiple times.

Worldwide passenger traffic grew from approximately 1.5 billion to more than 2.3 billion

passengers in the decade from 1997 to 2007. This corresponds to an average annual growth of

approximately 4.5% and an overall growth of approximately 55%. It is clear that the dynamic

upward trend of the period prior to the stagnation between 2001 and 2003 is now continuing.

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

2008-12-02 Annual Report 2007

Page 16 Release: 2.2

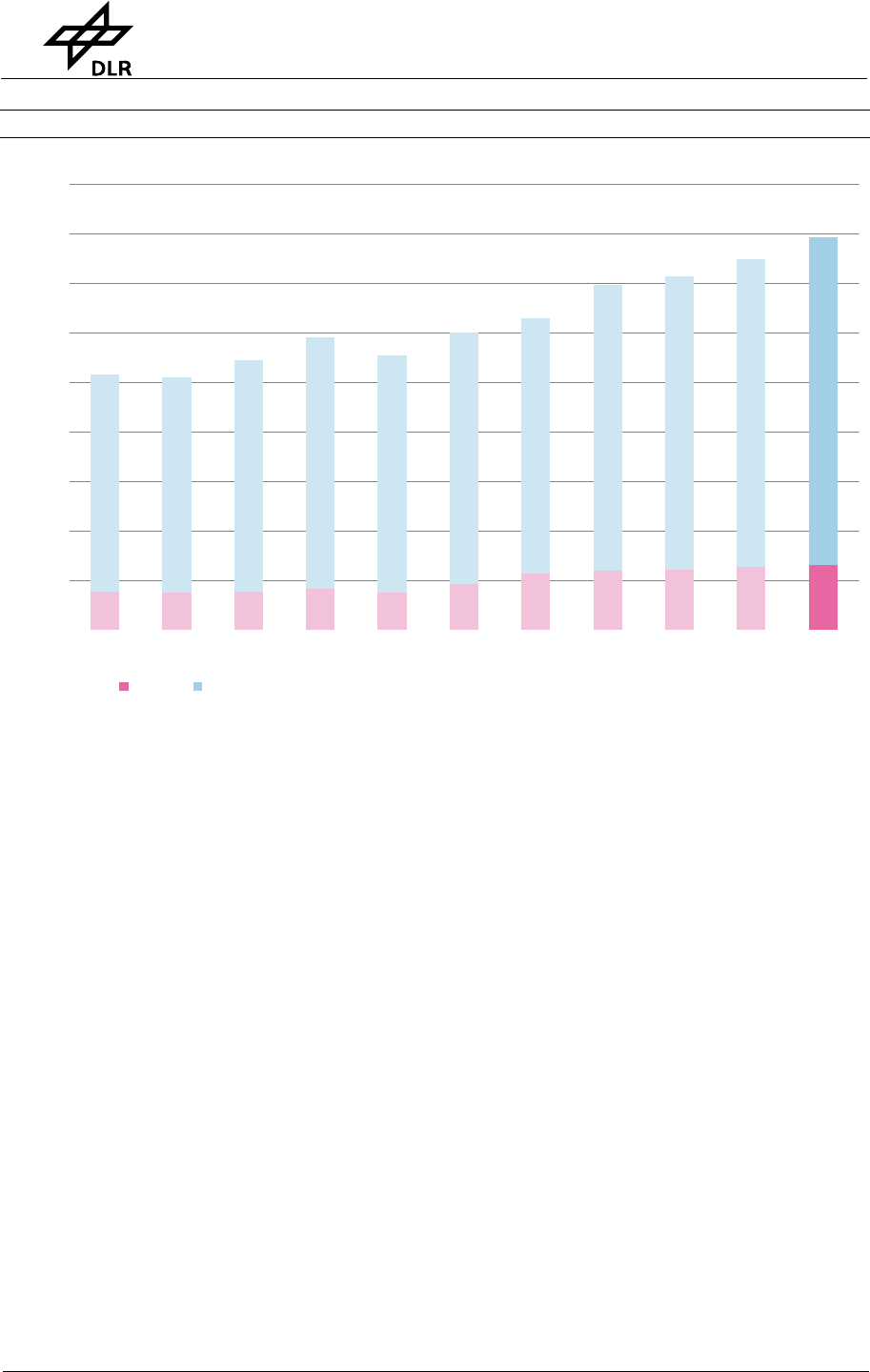

Figure 1-1: Development of the global passenger volume

Source: ICAO 2008

1019

1013

1069

1109

1092

1092

1130

1241

1317

1366

438

458

489

538

532

547

561

647

705

762

1432 828

0

500

1000

1500

2000

2500

1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007

Passengers carried (millions)

domestic international

International and domestic traffic differ in the pace of their development. In the decade 1997 to

2007, the annual volume of international traffic increased from 438 million to 828 million

passengers carried. This corresponds to an average annual growth rate of 6.6%. In the same

period, the level of domestic traffic increased from 1019 million to 1432 million passengers

carried. This corresponds to an average annual growth rate of only 3.5%. Thus, the proportion

of passengers carried on international flights increased from 30.1% to 36.6%, whereas the

proportion of passengers carried on domestic flights decreased from 69.9% to 63.4% in the

same period.

During the period studied (1997 to 2007), the number of passenger kilometres grew more

significantly than the passenger volume. Figure 1-2 shows the development of scheduled airline

traffic levels worldwide in terms of passenger kilometres performed each year.

+ 6.2%

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

Annual Report 2007 2008-12-02

Release: 2.2 Page 17

Figure 1-2: Development of the global passenger kilometres

Source: ICAO 2008

1,105

1,115

1,174

1,239

1,214

1,228

1,281

1,430

1,522

1,583

1,468

1,512

1,614

1,779

1,716

1,736

1,739

2,015

2,200

2,358

1,656.60 2,544.54

0

500

1,000

1,500

2,000

2,500

3,000

3,500

4,000

1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007

Passenger-km performed (billions)

domestic international

Since 1997, the level of traffic has increased from 2,573 billion passenger kilometres to

approximately 4,201 billion passenger kilometres. This corresponds to a growth of 63%,

compared to the growth in traffic volume of 55% discussed above.

1.1.2 Passenger Traffic Flows between the World Regions

The illustration below shows worldwide passenger flows (based on IATA data) and provides an

insight into the importance of air traffic for the different world regions. It is important to note

that the IATA data differs from the ICAO data. Furthermore, distortions are likely to occur with

respect to some aspects of the traffic structure, since not all airlines are IATA members.

According to IATA, their regional statistics on passenger traffic reflect approximately 87% of the

total volume achieved by IATA members. The values shown only reflect the levels recorded by

IATA. Please note also that the map only shows the main flows between the IATA-defined world

regions: North America, Central America, South America, Europe (including Russia), Africa,

Middle East, Asia and Oceania.

+ 6.6%

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

2008-12-02 Annual Report 2007

Page 18 Release: 2.2

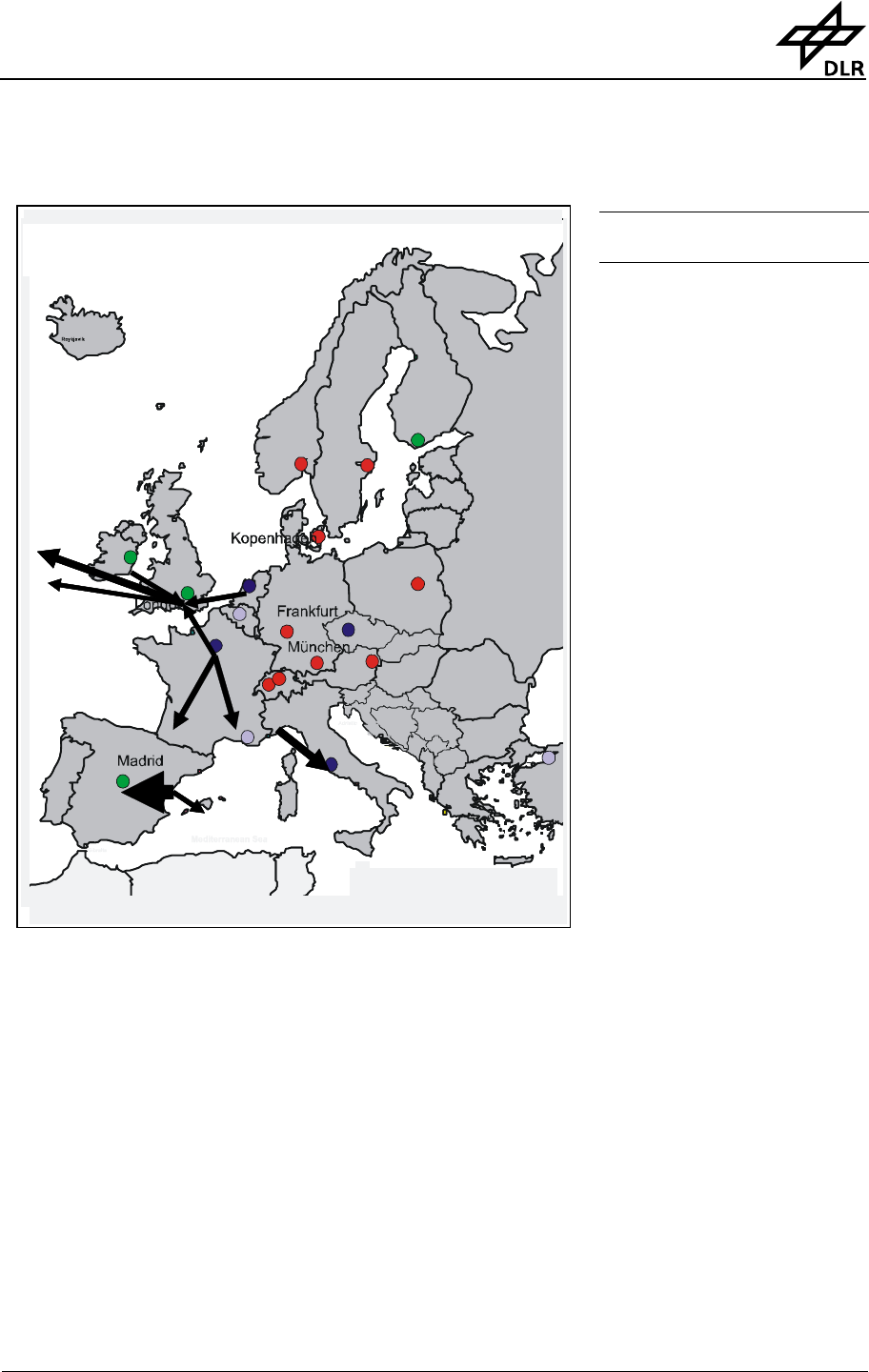

Figure 1-3: The main passenger flows between world regions (2007)

Source: IATA WATS 52

nd

Edition

27.9 (27.9)

33.3

10.3

57.3

36.4

16.0

19.7

22.7

15.7

Million passengers carried

(+7.6%)

(+0.3%)

(+4.9%)

(+8.4%)

(+11.5%)

(+12.5%)

(+16.2%)

(+5.5%)

(+0.9%)

(+0.3%)

27.9 (27.9)

33.3

10.3

57.3

36.4

16.0

19.7

22.7

15.7

Million passengers carried

(+7.6%)

(+0.3%)

(+4.9%)

(+8.4%)

(+11.5%)

(+12.5%)

(+16.2%)

(+5.5%)

(+0.9%)

(+0.3%)

On the "North Atlantic route" between North America and Europe, passenger traffic increased

by 7.6% to 57.3 million passengers in the last year. This makes it by far the most significant

traffic flow between the world regions. The route with the second largest volume, between

Europe and the Far East, also saw an increase in passenger traffic over the last year. On the

latter route, traffic grew by 5.5% to 36.4 million passengers. Approximately 16.0 million

passengers (an increase of 11.5%) travelled between Europe and Africa using airlines that

submit data to the IATA regional statistics. For the African region, traffic was mainly

concentrated on a few North African countries that are preferred holiday destinations. On the

Pacific routes between North America and the Far East, passenger traffic increased slightly by

approximately 0.3% to 27.9 million passengers. Other significant passenger flows are seen

between North America and Central America (33.3 million passengers), between North America

and South America (10.3 million passengers), between Europe and the Middle East (19.7 million

passengers) and between the Far East and Oceania (15.7 million passengers).

1.1.3 Global Freight Volume

In 2007, the ICAO reported worldwide freight traffic to be nearly 41.6 million tonnes. This

represents an increase in freight traffic of 57.6% over the period 1997 to 2007. Figure 1-4

shows the trend over the past decade (1997 to 2007). It should be noted when attempting to

interpret the data that the US Department of Transportation (DOT) changed the survey basis for

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

Annual Report 2007 2008-12-02

Release: 2.2 Page 19

domestic freight traffic in 2003. Domestic freight carried by non-scheduled airlines was not

considered until 2002, but thereafter was counted as domestic freight carried by scheduled

airlines. The corresponding values are shown accordingly in the ICAO statistics. In 2003, this

measure caused a 2% increase in the total recorded volume of worldwide air freight traffic.

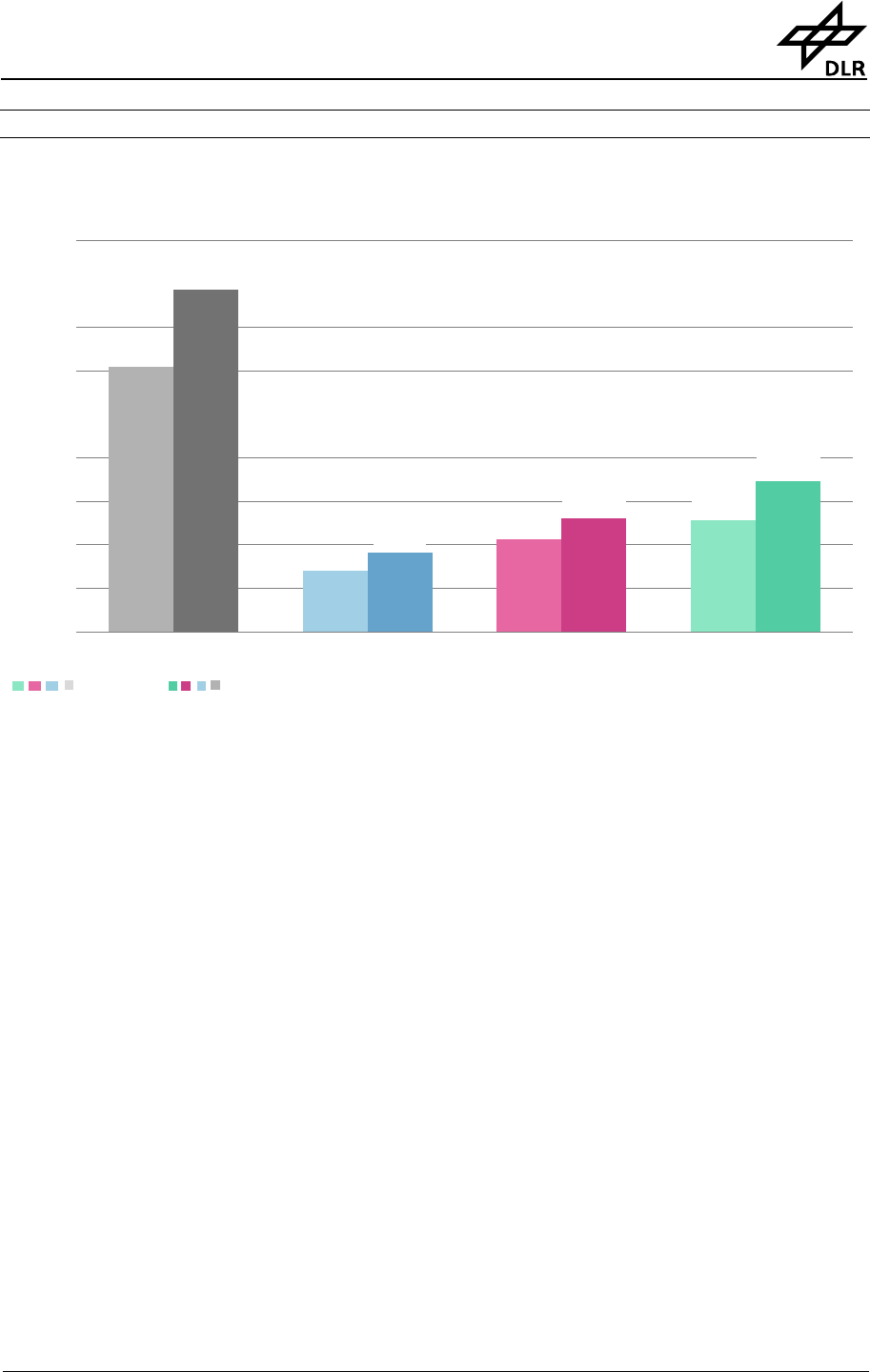

Figure 1-4: Development of the global freight traffic volume

Source: ICAO 2008

10.7

10.7

10.8

11.4

10.6

12.6

13.9

14.9

15.2

16.2

15.7

15.8

17.3

18.8

18.0

18.8

19.6

21.8

22.6

23.6

16.3 25.3

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007

Freight tonnes carried (millions)

domestic international

The increase in the quantity of air freight has seen different growth rates for cross-border and

domestic traffic. In the decade from 1997 to 2007, the amount of international air freight

increased by a total of 61.1% to the current level of 25.3 million tonnes in 2007. For domestic

air freight traffic, the quantity was 16.3 million tonnes in 2007, which represents an increase of

5.6 million tonnes, or 52.3%, over the level in 1997. The proportion of international freight was

approximately 61% in 2007. Whereas domestic traffic plays the more significant role for

passenger transport, for the freight sector international traffic is more important.

This fact is even more apparent if one considers the performance levels shown in Figure 1-5. This

measurement shows that in 2007 approximately 83% of worldwide air freight traffic was

international traffic. Worldwide, total freight traffic increased from 102.9 billion freight tonne

kilometres to 158.4 billion freight tonne kilometres in the decade from 1997 to 2007, which

corresponds to an increase of 54%. This means that the volume of air freight traffic saw an

almost identical increase when compared to passenger traffic levels over the same period.

+ 4.5%

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

2008-12-02 Annual Report 2007

Page 20 Release: 2.2

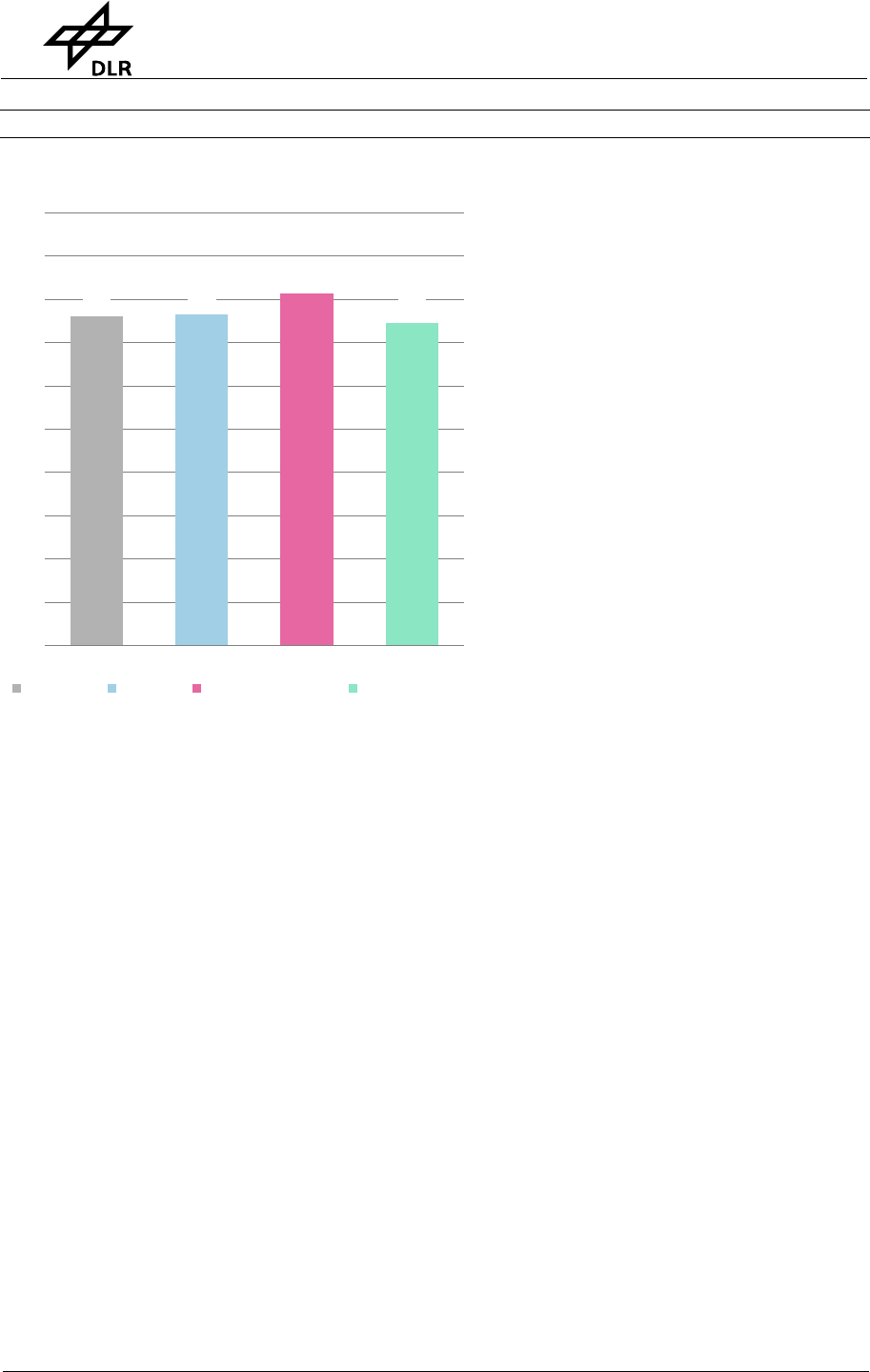

Figure 1-5: Development of the global freight tonne-kilometres

Source: ICAO 2008

15.1

14.8

15.4

16.4

14.8

18.3

22.6

23.9

24.1

25.5

87.7

87.1

93.3

101.5

96.0

101.6

103.1

115.1

118.4

124.2

26.0 132.4

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007

Tonne-km performed (billions)

domestic international

1.1.4 Freight Traffic Flows between the World Regions

In contrast to the regional distribution of global passenger traffic, freight traffic is concentrated

on just a few corridors. The majority of freight was carried on three main routes:

Between North America and the Far East (over 3.9 million tonnes)

Between Europe and the Far East (over 3.9 million tonnes)

Between North America and Europe (over 3.1 million tonnes)

Further major flows of freight were seen between Europe and the Middle East (1.1 million

tonnes), between the Middle East and the Far East (0.9 million tonnes in 2006), between Europe

and Africa (0.6 million tonnes in 2006), between the Far East and Oceania (0.6 million tonnes in

2007) and between North America and South America (0.5 million tonnes). According to the

IATA, traffic levels did not grow on the Pacific route in 2007, whereas North Atlantic traffic grew

by 5.7% and the flow of freight between Europe and the Far East grew by 4.8%.

+ 5.8%

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

Annual Report 2007 2008-12-02

Release: 2.2 Page 21

Figure 1-6: The main freight traffic flows between world regions (2007)

Source: IATA Regional Flow Statistics and IATA Origin-Destination Statistics

(3,947)

3,947

(-0.9%)

446

3,112

(+5.7%)

3,931

(+4.8%)

600

1,142

920

581

Freight tonnes carried (in thousands)

(+10.5%)

(+0.8%)

(+8.9%)

(+9.1%)

(+4.3%)

(3,947)

3,947

(-0.9%)

446

3,112

(+5.7%)

3,931

(+4.8%)

600

1,142

920

581

Freight tonnes carried (in thousands)

(+10.5%)

(+0.8%)

(+8.9%)

(+9.1%)

(+4.3%)

1.1.5 Comparison of Passenger and Freight Volume of Europe and the other

World Regions

Table 1-1 shows the growth rates of selected air transport indicators, which are reported by the

IATA and grouped in six different world-areas. The growth rates are based on the comparison of

the period January - December 2007 versus January - December 2006. The values of each area

are obtained by combining the air traffic performance of all IATA airlines resident in the

respective area. Industry means all IATA-Airlines taken together.

Table 1-1: Growth rates of

selected indicators

Source: IATA Monthly Traffic

Analysis December 2006 and

2007

Airlines based in the world

areas North America,

Europe, and Asia/Pacific

altogether achieved

approx. 90% of the world passenger kilometres in 2007. In 2007, the European IATA airlines

had a lower traffic growth than the whole industry. For example, RPK growth of all IATA Airlines

was 7.4%, while the RPKs performed by European IATA Airlines grew by only 6.0%. Only the

RPK Growth ASK Growth PLF FTK Growth ATK Growth

Africa 8.0% 7.0% 69.2 -6.0% 5.6%

Asia/Pacific 7.3% 5.7% 76.0 6.5% 6.2%

Europe 6.0% 5.2% 77.5 2.7% 3.9%

Latin America 8.4% 9.1% 72.9 -5.4% 7.8%

Middle East 18.1% 14.5% 75.9 10.1% 13.9%

North America 5.5% 4.6% 80.9 0.7% 2.1%

Industry 7.4% 6.2% 77.0 4.3% 5.3%

Jan-Dec 2007 vs. Jan-Dec 2006

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

2008-12-02 Annual Report 2007

Page 22 Release: 2.2

airline industry of North America had lower growth rates. Very high growth rates in 2007 are to

be observed in the Middle East.

1.2 Air Traffic in EU-27

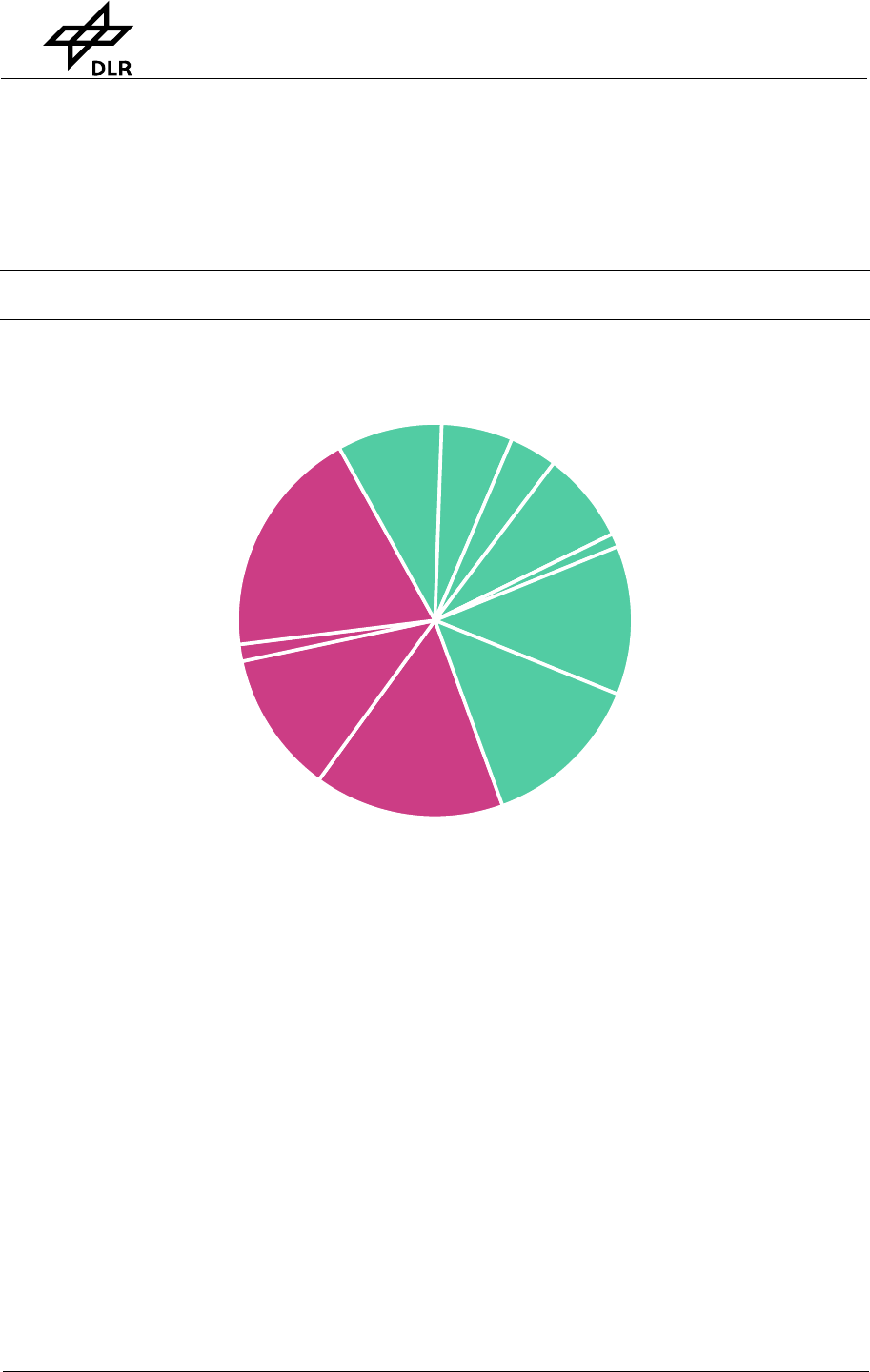

1.2.1 European Passenger Traffic

Figure 1-7: Development of Passenger

Traffic in the EU-27

Source: EUROSTAT

According to the Statistical Office of

the European Communities,

EUROSTAT, a total of 792 million

passengers were transported by air in

EU Member States in 2007.

Compared to the preceding year, this

corresponds to a growth of approx.

7.2%. The total traffic in 2007

consists of domestic air traffic (175.8

million passengers, which

corresponds to approx. 22.2% of the

total traffic), intra-EU air traffic

(345.9 million passengers; 43.7%)

and also extra-EU air traffic (270.4

million passengers; 34.1%, see

Figure1-7).

1.2.2 Passenger Traffic Flows between EU Member States

Compared to 2006, the main passenger flows remained almost unchanged in 2007 (see Table

1-2). The strongest passenger flow is seen again between the UK and Spain (almost 36 million

passengers). However, passenger demand increased by only 2.0% from 2006 to 2007 on this

country pair. In 2007, 22 million passengers were carried (increase of 3.9%) between Germany

and Spain. Number 3 of the strongest intra-European flows (between UK and Ireland, 12.1

million passengers) shows a slight decrease of 1.3%. Extremely strong growth of the already

large volume (10.2 million passengers) is shown by the flow between Italy and Spain. Here,

passenger traffic increased by almost 21.4%. At the same time, passenger demand between

Germany and Italy increased slightly. Poland and Cyprus appear as the only new EU Member

States among the Top 25 ranking of the biggest European country pairs represented by Poland –

UK, UK - Cyprus and Poland – Germany.

175,758

345,905

270,389

166,794

319,616

248,487

0

100,000

200,000

300,000

400,000

500,000

600,000

700,000

800,000

900,000

2006 2007

Passengers in 1,000

Domestic Intra EU-27 Extra EU-27

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

Annual Report 2007 2008-12-02

Release: 2.2 Page 23

Table 1-2: Main Passenger

Traffic Flows between EU

Member States in 2007

Source: EUROSTAT

1.2.3 Passenger Traffic

Flows between the

EU-27 and other World

Regions

The EUROSTAT air traffic

statistics also provides data

on passenger flows

between EU-27 and non-

EU countries. In total,

approx. 270 million

passengers were carried

from and to other regions

in the year 2007. Table 1-3

shows the main passenger

flows between EU-27 and

selected world regions.

Table 1-3: The main passenger flows of

the EU-27 from/to selected world

regions in 2007

Source: EUROSTAT

The passenger flow between EU-27

and non-EU-27 countries (85 million

passengers) consisted mainly of the

passenger traffic between the EU

and Switzerland and the EU-27 and

Turkey. The flight routes between

the EU-27 and Norway, the South

East European region (the states of

the former Yugoslavia) and the

Commonwealth of Independent

States contributed much less to the traffic of non-EU Europe. For intercontinental traffic, the

relation between the EU and North America was by far the most important one. More than 60

change to

2006

UK

↔

Spain 35,606 2.0%

Germany

↔

Spain 22,138 3.9%

UK

↔

Ireland 12,111 -1.3%

UK

↔

France 12,036 1.7%

Germany

↔

UK 11,533 0.8%

UK

↔

Italy 11,207 6.3%

Germany

↔

Italy 10,944 3.6%

Italy

↔

Spain 10,217 21.4%

UK

↔

The Netherlands 8,358 1.2%

France

↔

Spain 8,087 19.0%

France

↔

Italy 7,748 12.1%

Germany

↔

France 7,310 6.2%

Germany

↔

Austria 5,590 13.3%

UK

↔

Greece 5,454 -1.2%

UK

↔

Portugal 5,273 11.2%

Spain

↔

The Netherlands 5,031 8.7%

Germany

↔

Greece 4,993 4.3%

UK

↔

Poland 4,108 33.6%

Spain

↔

Ireland 3,592 16.3%

Spain

↔

Belgium 3,461 1.6%

UK

↔

Cyprus 2,976 -1.3%

Spain

↔

Portugal 2,947 27.5%

Italy

↔

The Netherlands 2,859 6.0%

Germany

↔

The Netherlands 2,607 -3.4%

Germany

↔

Poland 2,600 12.2%

Passengers 2007 in thousand

million

change to

2006

Europe exept EU 85.2 11.5%

North America 60.1 5.6%

Central America/Caribbean 11.1 -0.3%

South America 9.8 3.6%

Asian Republics of the Ex-USSR 1.4 12.0%

Near and Middle East 21.4 13.6%

Indian Sub-Continent 7.7 6.4%

Far East 26.1 4.8%

Oceania 1.8 -3.4%

North Africa 31.1 11.9%

Rest of Africa 14.1 6.1%

EU27: Passenger Flows from/to selected other Regions

in 2007

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

2008-12-02 Annual Report 2007

Page 24 Release: 2.2

million passengers (5.6% growth) were carried. Another significant intercontinental flow is the

one between Europe and Far East with the countries Japan, China, and Korea. Between the EU

and the Indian Sub-Continent, the demand grew by 6.4% up to 7.7 million passengers. In 2007,

further important passenger flows were seen between the EU-27 and North Africa with 31

million passengers (almost 12% growth), the Near and Middle East (21.4 million passengers)

and the rest of Africa (14 million passengers).

Figure 1-8: Share of world regions in extra-EU-27 traffic

Source: EUROSTAT

Figure 1-8 shows the share of different world regions in the extra-EU-27 traffic. The European

non-EU (31.6% of the total traffic of extra-EU-27), North American (22.3%) and North African

(approx. 11.5%) regions dominate the demand, accounting for more than 65% of all extra-EU-

27 passenger traffic. The Near & Middle East with almost 8%, the Far East with nearly 10% and

South Africa with 3.6% had lower shares. The smallest flow appeared to be Australia, the South

Sea Islands and Antarctica with barely 0.67%. One reason could be the fact that those

passengers who either stop-over or change planes will not be allocated to the country of their

final destination.

1.2.4 European Air Freight Traffic Volume

Besides the data on passenger traffic in the EU Member States, EUROSTAT also collects and

publishes information on the transportation of mail and goods. In contrary to passenger

transport, where in most cases journeys form a round trip, freight and mail are usually just

carried from the point of origin to the point of destination. Therefore, so-called „unpairs” are

likely to occur on the individual traffic relation, which for example means that between two

countries more goods are carried in one direction than in the other one. Furthermore it should

be noted that the declared destination airport is not necessarily the final destination airport of

the shipment.

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

Annual Report 2007 2008-12-02

Release: 2.2 Page 25

Figure 1-9: Freight and Mail carried in the EU in 2006 and 2007

Source: EUROSTAT

To, from and within the EU-27, a

total of approx. 12.6 million tonnes

of freight and mail were handled in

the year 2007. This comprises of

shipments loaded and unloaded at

airports in EU Member States. The

mentioned total of 12.6 million

tonnes consists of 0.66 million

tonnes of freight and mail carried on

domestic routes, 2.0 million tonnes

of shipment carried on routes

between EU Member States and

nearly 10 million tonnes of shipment

carried on routes to non-EU

countries (see Figure 1-9).

Compared to 2006, the total freight

of 11.8 million tonnes increased by

6.6%. Whereas domestic traffic decreased considerably (-4.2%), intra-EU traffic increased

significantly by 11.6% and extra-EU traffic by 6.4%.

1.2.5 Freight Traffic Flows between EU-27 Member States

As already mentioned, freight traffic “unpairs” are likely to occur on individual traffic relations.

Consequently, the main freight and mail flows between individual EU Member States are

displayed in a destination-oriented way (see Table 1-4 on the next page).

Compared to the large intercontinental freight flows, the quantity of freight carried between the

individual EU Member States is rather low. The freight flow from Germany to UK shows the

highest volume (approx. 73,100 tonnes). However, in the opposite direction only approx.

52,100 tonnes were transported. From Belgium to the UK there is a similar, large freight flow.

Belgium plays – considering its economic power – an outstanding role with respect to the

individual intra-European freight relations due to the already mentioned operation of handling

points for big express-forwarding companies. Thus, besides the already mentioned flow from

Belgium to the UK, also the flows from the UK to Belgium (40,600 tonnes), from Germany

(39,900 tonnes) and from Italy (34,800 tonnes) to Belgium and also from Belgium to Spain

(35,100 tonnes) and Italy (31,700 tonnes), show a considerably high volume. Strong freight and

mail flows originate from Germany and target France (52,700 tonnes), Spain (46,600 tonnes),

Italy (37,100 tonnes), and Sweden (32,100 tonnes). To Germany, a relatively high volume of

2,024

9,910

687

658

1,814

9,311

0

2,000

4,000

6,000

8,000

10,000

12,000

14,000

2006 (EU-25) 2007 (EU-27)

Freight & Mail in 1,000 t

Domestic Intra-EU Extra-EU

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

2008-12-02 Annual Report 2007

Page 26 Release: 2.2

shipments is carried from France (46,300 tonnes), Italy (35,100 tonnes) and Belgium (33,100

tonnes).

Table 1-4: Important Freight Traffic Flows between EU Member States in 2007

Source: EUROSTAT

origin destination

thousand

tonnes

change to

2006

Germany

→

UK 73.1 4.3%

Germany

→

France 52.7 12.8%

UK

→

Germany 52.1 7.9%

Belgium

→

UK 50.4 4.1%

Germany

→

Spain 46.6 3.8%

France

→

Germany 46.3 18.1%

UK

→

Belgium 40.6 -4.7%

Germany

→

Belgium 39.9 5.3%

Germany

→

Italy 37.1 1.4%

Belgium

→

Spain 35.1 -4.6%

Italy → Germany 35.1 16.1%

Italy

→

Belgium 34.8 -5.5%

Belgium

→

Germany 33.1 24.9%

Germany

→

Sweden 32.1 6.3%

Belgium

→

Italy 31.7 0.3%

Belgium

→

France 29.7 3.5%

Spain

→

Germany 23.1 -0.4%

France

→

UK 22.5 14.8%

UK

→

Ireland 22.0 0.5%

Belgium

→

Sweden 21.9 1.9%

Italy

→

UK 21.9 14.9%

Freight flows in 2007

1.2.6 Freight Traffic Flows between the EU-27 and other World Regions

Table 1-5 shows the main linkages between the EU-27 and selected world regions. It should be

noted – as already described before – that the flights’ origins and destinations are not

necessarily identical with the regions of origin and destination of the goods carried. Thus, the

relations to the region Middle East show the third highest volume of freight and mail carried

compared to all relations considered. In 2007, more than 724,000 tonnes were carried from the

EU-27 to the Middle East region (7.2% increase) and more than 690,000 tonnes were received

from this region (0.9% increase). However, the major part of these shipments were probably not

originally from or destined for the region Middle East, but other parts of Asia and were only

transhipped in the Middle East. For example, big transhipment facilities operate at the airports in

Dubai and Doha (Emirate Qatar). The main linkage with regard to air freight/mail transport is

seen between Europe and North America. 1.4 million tonnes were carried towards the West (-

0.3% growth), and more than 1.3 million tonnes towards the East (7.1% growth). Furthermore,

the corridor EU-27 – East Asia (among others China, Japan and Korea) shows a large transport

volume. 1,210,000 tonnes (9.1% growth) were carried from the EU-27 directly to East Asia,

whereas more than 1.6 million tonnes have been received from this region by direct flights.

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

Annual Report 2007 2008-12-02

Release: 2.2 Page 27

Further linkages occurred between the EU-27 and the Commonwealth of Independent States

(CIS; including Russia) and also the South Asia region including countries such as India, Pakistan,

Bangladesh and Nepal.

Table 1-5: Important Air Freight Traffic Flows between the EU-27 and other countries and regions of the

world in 2007

Source: EUROSTAT

unloaded from +/- to 2006 loaded to +/- to 2006

Norway 5909 12.7% 9731 -1.9%

Iceland 12260 -15.9% 15242 2.4%

Switzerland 31905 5.4% 25428 -2.3%

Turkey 98672 9.2% 98173 13.8%

Southeast Europe 3169 23.3% 7542 49.0%

CIS 250099 1.9% 191169 8.9%

East Africa 177054 6.7% 59167 -1.7%

North Africa 152760 55.9% 140256 26.3%

Central Africa 8793 1.5% 18841 8.0%

Africa South 142587 3.9% 153382 17.6%

West Africa 61608 -6.1% 148391 32.4%

North America 1323105 7.1% 1412281 -0.3%

Central America/Caribbean 76070 5.0% 108549 -1.3%

South America 217813 4.4% 217579 15.5%

East Asia 1672242 7.9% 1210581 9.1%

South Asia 239085 5.0% 201101 22.5%

Middle East 690033 0.9% 724376 7.2%

Oceania 39607 -5.2% 38730 -4.3%

EU-27: loaded and unloaded Freight in 2007 in tonnes

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

2008-12-02 Annual Report 2007

Page 28 Release: 2.2

1.3 Air Traffic in EU Member States

1.3.1 Passenger Volume

An increase of passenger traffic in the individual EU Member States (see Fig. 1-10 and 1-11) is

revealed in all cases in the time frame 2005 to 2007. Among the former EU-15 Member States,

in the time from 2006 to 2007, Portugal (10.4%), Austria (10.1%), Spain (8.6%) as well as

Finland, Belgium, Ireland and Italy all show above average growth rates (approx. 7.2%). Leading

members of the high traffic group are the United Kingdom (217 million passengers, 2.9%

growth), ahead of Germany (164 million passengers, 6.3% growth) and Spain (163 million

passengers). Strong growth can also be seen in most new EU Member States. Romania (41%),

Latvia (26.8%), Poland (24.6%) and Lithuania (22.8%) showed the highest passenger growth

figures.

Figure 1-10: Passenger Traffic of the former EU-15 Member States

Source: EUROSTAT

0

25,000

50,000

75,000

100,000

125,000

150,000

175,000

200,000

225,000

Au

s

tria

B

elgi

u

m

Denmark

Fin

lan

d

France

Ge

rma

ny

Greece

I

re

land

Ital

y

L

u

xembourg

N

eth

erland

s

Portugal

Spain

Sweden

U

n

ited

King

d

om

Passengers in 1,000

2005 2006 2007

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

Annual Report 2007 2008-12-02

Release: 2.2 Page 29

Figure 1-11: Passenger Traffic of the 12 new EU Member States

Source: EUROSTAT

0

2,500

5,000

7,500

10,000

12,500

15,000

Cy

prus

Czec

h

R

ep

u

bl

i

c

Es

to

n

ia

Hungary

La

tv

ia

Lith

u

an

i

a

Malt

a

Pol

a

nd

Sl

o

vakia

Slovenia

B

u

l

g

ari

a

R

o

mania

Passengers in 1,000

2005 2006 2007

1.3.2 Freight volume

It can be seen that there is a high quantity of freight and mail carried in those individual EU

Member States which are also outstanding with respect to passenger traffic such as Germany

(3.6 million tonnes) and the UK (2.4 million tonnes) in the year 2007. However, smaller countries

like Luxemburg (0.7 million tonnes), the Netherlands (1.5 million tonnes) and Belgium (1.4

million tonnes) also have a relatively high freight and mail traffic. A country’s traffic is

determined by its economic activities and the corresponding freight and mail flows. Thus,

Germany is an important country of origin and destination for shipments carried by air.

Furthermore, high handling volume, due to the country’s relevance with respect to logistic cycles

of air transport, is likely to occur. Amsterdam Airport is an important international hub for

passenger traffic. Since a lot of air freight and air mail are carried on passenger flights, the

airport is considered to be of similar importance for the handling of cargo shipments. Although

there is no mega-hub for passenger traffic in Belgium, the airports of Brussels and Liège operate

as important points for air freight handled by large express/forwarding companies.

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

2008-12-02 Annual Report 2007

Page 30 Release: 2.2

Figure 1-12: Freight Traffic of the former EU-15 Member States

Source: EUROSTAT

0

500

1000

1500

2000

2500

3000

3500

4000

Austria

B

el

g

iu

m

Denmark

Fi

n

la

nd

F

ra

n

c

e

German

y

Gre

ec

e

Ireland

I

t

aly

Luxemb

o

ur

g

Ne

th

erl

an

d

s

P

ortugal

Sp

ai

n

Sw

e

d

en

United

Kin

g

d

o

m

Freight in 1,000 tonnes

2005 2006 2007

Figure 1-13: Freight Traffic of the 12 new EU Member States

Source: EUROSTAT

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

Cy

p

ru

s

Czech R

ep

u

b

li

c

Est

o

nia

Hungary

Latvia

L

i

thuania

Malta

Poland

Slovakia

Sl

o

v

en

i

a

B

ulgari

a

R

o

man

i

a

Freight in 1,000 tonnes

2005 2006 2007

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

Annual Report 2007 2008-12-02

Release: 2.2 Page 31

1.3.3 Flight Volumes in EU Member States

Besides the traffic measured by the number of passengers and the amount of goods handled in

each country – the demand side of air transport – also the number of flights performed

constitutes an essential metric for air traffic. Figure 1-13 shows flight movements performed in

European countries in 2007. Whereas the statements on European traffic development, as given

in the preceding chapters, are based on data provided by EUROSTAT, data provided by the

European Organisation for the Safety of Air Navigation, EUROCONTROL, is now used. This data

is not directly comparable with that provided by EUROSTAT. On the one hand it does not only

refer to EU Member States, on the other hand it includes all flights performed according to

Instrument Flight Rules (IFR). IFR flights are not identical to those indicated by EUROSTAT in the

air traffic statistics. However, the flights indicated in the EUROSTAT air traffic statistics constitute

the major part of IFR flights recorded by EUROCONTROL. Besides airplanes departing from or

arriving in a country, overflights are also relevant for the evaluation and planning of en-route

airspace capacity. Overflights are performed by airplanes only crossing a country’s territory in the

air and thus do not take-off or land there.

Figure 1-14 shows the respective flights of each EU-member country, broken down by

departures, arrivals, domestic flights (here each flight includes the take-off and landing

procedure), as well as overflights. The number of overflights in a country does not necessarily

account for the importance of a country in terms of traffic, but its size as well as its position in

Europe. Thus, for example, the Netherlands show a high number of overflights compared to the

number of arrivals and departures. The same is true for Austria and Belgium/Luxemburg. Flights

departing from and arriving at airports located in the same country are called domestic flights.

For this parameter, the size of a country (in terms of both geographical size and population)

matters. European countries showing a distinct number of domestic flights are France, Germany,

Italy, Spain and the UK. For these countries, a high number of overflights is also indicated. For

the parameter departures and arrivals, major European countries are the UK, Germany, France,

Spain and Italy. When considering the totals of all categories, Germany is number one (about

3.2 million flight movements in 2007), followed by France (3.0 million) and the UK (2.5 million).

In total, approx. 9.7 million flights were recorded in Europe (including non-EU members) in

2007, with approx. 1 million arrivals and departures each, which crossed the border of the

Eurocontrol district, 7.6 million domestic flights within the Eurocontrol district and about 0.1

million flights which crossed the Eurocontrol district. Compared to 2006, flight movements

increased by about 5.1%. When considering flight movement growth in each country, high

growth rates in Central and East European countries are revealed. For example, flight movement

traffic in Lithuania grew by approx. 16.9% and in Latvia by 15.6%. However, when looking at

the absolute figures, these countries show only moderate traffic. Major countries in terms of

flight movement traffic show comparatively average growth (Germany 4.7%, France 5.9%, Italy

8.6%, Spain 8.5% and the UK 3.5%). According to Eurocontrol, August 31

st

, 2007 was the

busiest day ever. The states of the European Civil Aviation Conference recorded 33,506 IFR

flights on this day.

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

2008-12-02 Annual Report 2007

Page 32 Release: 2.2

Figure 1-14: IFR Flights in EU Member States in 2007

Source: Eurocontrol

0 1,000,000 2,000,000 3,000,000 4,000,000

AUSTRIA

BELGIUM/LUXEMBOURG

BULGARIA

CROATIA

CYPRUS

CZECH REPUBLIC

DENMARK

ESTONIA

FINLAND

FRANCE

GERMANY

GREECE

HUNGARY

IRELAND

ITALY

LATVIA

PORTUGAL (excl. Azores)

LITHUANIA

MALTA

NETHERLANDS

ROMANIA

SLOVAKIA

SLOVENIA

SPAIN

SWEDEN

UNITED KINGDOM

IFR Flights

DEPARTURES ARRIVALS INTERNALS OVERFLIGHTS

Annual analyses of the European air transport market

Annual Report 2007

Annual Report 2007 2008-12-02

Release: 2.2 Page 33

1.4 Flight Efficiency

Flight efficiency is determined by the relationship between the optimal flight distance (in terms

of energy, cost and capacity) and the distance actually flown. For air traffic in Europe,

Eurocontrol calculates this flight efficiency by means of radar data collected and model

calculations of the optimal flight distances. The determination of flight efficiency requires

distinction between horizontal and vertical flight efficiency. The horizontal flight efficiency refers

to discrepancies from – as a rule – the shortest distance between the airports of departure and

destination. The vertical efficiency describes negative discrepancies with respect to the optimal

flight altitude, for example, in the case that an airplane has to be flown higher than required

from an operational point of view, due to the weather conditions. Just recently, Eurocontrol

have also emphasized the aspects of vertical flight efficiency.

Eurocontrol has published final data on flight efficiency for 2007 in its “Performance Review

Report 2007”. In the European airspace, monitored by Eurocontrol, the average distance of all

flights is approx. 5.8% longer than the flight route covering the shortest distance between

departure and destination airport (the so-called Great Circle Distance). The mentioned 5.8%

corresponds to a circuitous distance of 48.9 km per flight, on the basis of all flights recorded. As

a strategic objective, the "Performance Review Commission" (a consultancy board for

Eurocontrol in the field of efficiency enhancement) specifies an optimisation of the circuitous

route distance by 2 km per year. This optimisation target was clearly not reached in 2007;

instead there was an increase in detours performed by airlines in Europe (+0.7 km per flight on

average). As to the flight efficiency of the individual European states, it becomes evident that