Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management

Naval Postgraduate School

NPS-HR-21-006

ACQUISITION RESEARCH PROGRAM

SPONSORED REPORT SERIES

Uniformed Military Acquisition Officer Career Path Development

Comparison

December 2020

Maj. Ashley R. McCabe, USMC

LCDR Paveena Ritthaworn USN

LCDR Darian J. Wilder, USN

Thesis Advisors: Dr. Robert F. Mortlock, Professor

Kelley Poree, Lecturer

Graduate School of Defense Management

Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited.

Prepared for the Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA 93943.

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management

Naval Postgraduate School

The research presented in this report was supported by the Acquisition Research

Program of the Graduate School of Defense Management at the Naval Postgraduate

School.

To request defense acquisition research, to become a research sponsor, or to print

additional copies of reports, please contact the Acquisition Research Program (ARP)

via email, arp@nps.edu or at 831-656-3793.

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management - i -

Naval Postgraduate School

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this research was to compare the career path development of the

Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force, and Army Acquisition Officers and identify advantages

and disadvantages from each Service. After an analysis of the differences, recommended

changes to establish greater efficiency and symmetry within the Acquisition Officer’s

professional development to serve more effectively in a Joint environment are proposed.

The methodology included comparing U.S. Armed Forces processes and frameworks

concerning career field education and training of uniformed Acquisition Officers in the

contract management and program management fields. Each Service’s methods were

compared to identify milestones for career progression of Acquisition Officers within each

Service. Processes that would benefit other Services were identified, such as serving in

non-acquisition positions as a junior officer and serving in back-to-back acquisitions tours

once joining the acquisition workforce. These beneficial processes were used to create a

Universal Acquisition Officer Career Path (UAOCP) that can be adopted by all Services to

better synchronize military and civilian education, training, and experience across the

Services for Acquisition Officers. The UAOCP would promote a level field of knowledge

that could better serve the Joint acquisition environment.

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management - ii -

Naval Postgraduate School

THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management - iii -

Naval Postgraduate School

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Ashley McCabe, Major, Supply Officer, U.S. Marine Corps, is a native of Bisbee,

AZ. She graduated from Virginia Military Institute, earning a Bachelor of Science degree

in mathematics. She commissioned in the Marine Corps through Officer Candidate School

in 2009. Maj McCabe’s initial tour was at Combat Logistics Regiment 3, III Marine

Expeditionary Force, Okinawa, Japan, as the Regimental Supply Officer. While there,

Maj McCabe participated in the Indo-Pacific multinational military exercise Cobra Gold

2012 and 2013, held in the Kingdom of Thailand; she also supported the 2013 annual

Reunion of Honor ceremony on Iwo To, marking the 69th anniversary of the pivotal World

War II Battle of Iwo Jima. Her second sea tour was at Weapons Training Battalion,

Quantico, VA. Here she served as the Supply Officer for 1 year, the Marine Corps Shooting

Teams Officer In-Charge for 1 year, and the Headquarters Company Commanding Officer

for the 3rd year. During this tour, Maj McCabe completed the Expeditionary Warfare

School distance education course. Maj McCabe’s third tour was at I Marine Expeditionary

(I MEF) Force Headquarters Group, Camp Pendleton, CA. During this time, Maj McCabe

assisted in the stand-up of the I MEF Information Group and I MEF Support Battalion, the

first new unit in the Marine Corps since World War II. While stationed in Camp Pendleton,

Maj McCabe participated in multiple Maritime Prepositioned Force exercises in the United

States and the United Arab Emirates. Maj McCabe’s personal decorations include the Navy

and Marine Corps Commendation Medal and Navy and Marine Corps Achievement Medal.

She is qualified as a Ground Safety Officer and a Maritime Prepositioned Force Staff

Planning Officer.

Paveena Ritthaworn, Lieutenant Commander Supply Corps Officer, U.S. Navy,

is a native of Bangkok, Thailand; she immigrated to the United States when she was 10

years old. She graduated from the University of Maryland, earning a bachelor’s degree in

business management, and she obtained an MBA from Strayer University. She enlisted in

the Navy in 2005 as a Personnel man and commissioned through Officer Candidate School

in 2008. LCDR Ritthaworn’s initial sea tour was as the Disbursing and Sales Officer aboard

the USS Emory S. Land (AS 39) in Bremerton, WA, and in the second year, Diego Garcia.

Her second sea tour was as the Supply Officer (SUPPO) aboard the USS San Antonio (LPD

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management - iv -

Naval Postgraduate School

17). Her third sea tour was as the Principal Assistant for services aboard the USS Gerald

R. Ford (CVN 78). Ashore, LCDR Ritthaworn completed the Joint Professional Military

Education (JPME I) curriculum while she was stationed at U.S. Forces Korea (USFK) J4.

She was the J4 Brigadier General’s Aide the first year, and the last two years she served as

the Current Operations Officer. Her second shore duty was as the Aviation Support

Detachment Officer at the Naval Supply Systems Command Fleet Logistics Center

(NAVSUP FLC) in Norfolk, VA. LCDR Ritthaworn’s personal decorations include the

Joint Commendation Medal, Joint Service Achievement Medal, Navy Commendation

Medal, and Navy and Marine Achievement Medal. She is qualified as a Surface Warfare

Supply Corps Officer (SWSCO) and Naval Aviation Supply Corps Officer (NASO).

LCDR Ritthaworn is married to Nirapat Homhual of Bangkok, Thailand. They have a son,

Plerng, age 9.

Darian Wilder, Lieutenant Commander, Supply Corps Officer, U.S. Navy, is an

Atlanta, GA, native. He graduated with distinction from Officer Candidate School in 2009.

He has a Bachelor of Business Administration degree from Savannah State University. His

Supply Corps sea duty assignment includes a tour on USS Chung-Hoon (DDG 93) as both

the Assistant Supply Officer and Supply Officer. His most recent sea duty tour was on the

USS Lake Champlain (CG 57) as the Supply Officer. His shore assignments include Navy

Acquisition Contracting Officer Intern at Fleet Logistics Center Pearl Harbor and Logistics

and Supply Department Head for the U.S. Naval Observatory in Washington, DC. He is

currently attending Naval Postgraduate School for an MBA with a specialization in

logistics information systems management. A prospective member of the acquisition

professional community, LCDR Wilder has earned the supply warfare qualification in

surface warfare and Defense Acquisition Workforce Improvement Act (DAWIA) Level II

in contracting and acquisition. LCDR Wilder’s personal awards include Navy and Marine

Corps Commendation Medals, the Air Force Commendation Medal, Army Commendation

Medals, Navy and Marine Corps Achievement Medals, and an Army Achievement Medal,

among other unit and campaign commendations from the U.S. Army and Georgia Air

National Guard. LCDR Wilder currently resides in Monterey, CA, with his wife of 17 years

and four children.

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management - v -

Naval Postgraduate School

NPS-HR-21-006

ACQUISITION RESEARCH PROGRAM

SPONSORED REPORT SERIES

Uniformed Military Acquisition Officer Career Path Development

Comparison

December 2020

Maj. Ashley R. McCabe, USMC

LCDR Paveena Ritthaworn USN

LCDR Darian J. Wilder, USN

Thesis Advisors: Dr. Robert F. Mortlock, Professor

Kelley Poree, Lecturer

Graduate School of Defense Management

Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited.

Prepared for the Naval Postgraduate School, Monterey, CA 93943.

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management - vi -

Naval Postgraduate School

THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management - vii -

Naval Postgraduate School

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................1

A. PROBLEM ...................................................................................................4

B. RESEARCH QUESTIONS .........................................................................5

C. WHY THIS RESEARCH IS IMPORTANT ...............................................5

D. METHODOLOGY ......................................................................................6

E. RESEARCH ROADMAP ............................................................................7

II. BACKGROUND .....................................................................................................9

A. PROGRAM MANAGEMENT ..................................................................15

1. Army ..............................................................................................16

2. Air Force ........................................................................................18

3. Navy ...............................................................................................19

4. Marine Corps .................................................................................21

B. CONTRACT MANAGEMENT ................................................................22

1. Army ..............................................................................................24

2. Air Force ........................................................................................25

3. Navy ...............................................................................................26

4. Marine Corps .................................................................................28

C. SUMMARY ...............................................................................................29

III. LITERATURE REVIEW ......................................................................................31

A. GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS ..........................................................32

B. GOVERNMENT REPORTS .....................................................................35

C. JOURNAL ARTICLES .............................................................................39

D. PREVIOUS THESES ................................................................................41

E. ANALYSIS OF REVIEWED LITERATURE ..........................................43

F. CONCLUSION ..........................................................................................44

IV. ANALYSIS ............................................................................................................47

A. EDUCATION ............................................................................................47

1. Program Management ....................................................................48

2. Contract Management ....................................................................52

3. Education Concluded .....................................................................54

B. TRAINING ................................................................................................55

1. Program Management ....................................................................56

2. Contract Management ....................................................................63

3. Training Concluded .......................................................................69

C. EXPERIENCE ...........................................................................................70

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management - viii -

Naval Postgraduate School

1. Program Management ....................................................................71

2. Contract Management ....................................................................77

3. Experience Concluded ...................................................................83

D. CURRENT SERVICE CAREER PATHS .................................................84

1. Army ..............................................................................................84

2. Air Force ........................................................................................85

3. Navy ...............................................................................................87

4. Marine Corps .................................................................................89

E. CONCLUSION ..........................................................................................91

V. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................93

A. CONCLUSIONS........................................................................................93

1. Advantages .....................................................................................94

2. Disadvantages ................................................................................94

B. DOD’S NEW INITIATIVE: “BACK-TO-BASICS” ................................96

C. RECOMMENDATION .............................................................................98

D. AREAS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH...................................................103

APPENDIX A. DAWIA PROGRAM MANAGEMENT CERTIFICATION

REQUIREMENTS ...............................................................................................105

APPENDIX B. DAWIA CONTRACT MANAGEMENT CERTIFICATION

REQUIREMENTS ...............................................................................................111

LIST OF REFERENCES .................................................................................................117

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management - ix -

Naval Postgraduate School

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1. Acquisition Workforce Demographics. Adapted from Human

Capital Initiatives (2020). ..........................................................................13

Figure 2. Bloom’s Taxonomy and DAU Courses. Source: Layton (2007). ..............14

Figure 3. Army Acquisition Corp Career Timeline. Adapted from DA (2010). .......17

Figure 4. Air Force PM Career Path. Source: DoAF (2012). ....................................19

Figure 5. Recommended Career Path for Navy AWF. Source: Everling et al.

(2017). ........................................................................................................21

Figure 6. USMC Acquisition Officer Career Roadmap. Source: Marine Corps

System Command (n.d.-c) .........................................................................22

Figure 7. Army Acquisition Corp Career Timeline. Adapted from DA (2010). .......25

Figure 8. Air Force PM Career Path. Source: DoAF (2012). ....................................26

Figure 9. Navy Supply Corps Career Progression Path. Source: Office of

Supply Corps Personnel (2011). ................................................................28

Figure 10. Acquisition Corps Requirements. Adapted from DON (2019a) ................30

Figure 11. Leading Practices by Military Services. Source: GAO (2018). .................36

Figure 12. Overall AWF Total. Source: Human Capital Initiatives (2020). ...............39

Figure 13. Professional Development Model (Officer). Source: Gambles et al.

(2009). ........................................................................................................41

Figure 14. Marine Corps Program Management Career Education

Requirements. Adapted from Marine Corps System Command (n.d.-

c). ...............................................................................................................52

Figure 15. Marine Corps Program Management Career Training Requirements.

Adapted from Marine Corps Systems Command (n.d.-c). ........................63

Figure 16. Army Acquisition Career Development Model. Source: DA (2018). .......73

Figure 17. Marine Corps Program Management Career Roadmap. Source:

Corps System Command (n.d.-c) ...............................................................77

Figure 18. Tactical Level Sight Picture for Buyers/Administrators. Source:

DoAF (2014). .............................................................................................80

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management - x -

Naval Postgraduate School

Figure 19. Operational Level for Commanders, Supervisors, and Staff Officers.

Source: DoAF (2014). ................................................................................81

Figure 20. Strategic Level Sight Picture for Strategic Leaders. Source: DoAF

(2014). ........................................................................................................81

Figure 21. Proposed USMC 3006 Career Roadmap. Source: Personal

communication W. Young (March 17, 2020). ...........................................83

Figure 22. Generic Army Acquisition Officer Career Path .........................................85

Figure 23. Generic Air Force Acquisition Officer Career Path ..................................86

Figure 24. Generic Navy Acquisition Officer Career Path .........................................89

Figure 25. Generic Marine Corps Acquisition Officer Career Path ............................91

Figure 26. Proposed Contracting Officer Certification Requirements. Source:

Linden (2020).............................................................................................97

Figure 27. Universal Acquisitions Officer Career Path ............................................100

Figure 28. Possible Career Paths Using the UAOCP ................................................102

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management - xi -

Naval Postgraduate School

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1. Uniformed Defense Acquisition Program Management Workforce

by Service...................................................................................................15

Table 2. Uniformed Defense Acquisition Contract Management Workforce

by Service...................................................................................................24

Table 3. Core Plus Recommended DAWIA Education. Source: DAU (n.d.). ........48

Table 4. Contracting Core and Core Plus Recommended DAWIA Education.

Source: DAU (n.d.). ...................................................................................52

Table 5. DAWIA Program Management Required Training for Certification.

Source: DAU (n.d.). ...................................................................................57

Table 6. Core Plus Recommended DAWIA Training for Program

Management. Source: DAU (n.d.) .............................................................57

Table 7. DAWIA Program Management Unique Position Training

Requirements. Source: DAU (n.d.). ...........................................................58

Table 8. USAF and DAU Program Management Track. Source: DoAF

(2012). ........................................................................................................60

Table 9. Air Force APDP Approximate Training Flow Chart. Source: DoAF,

2012............................................................................................................61

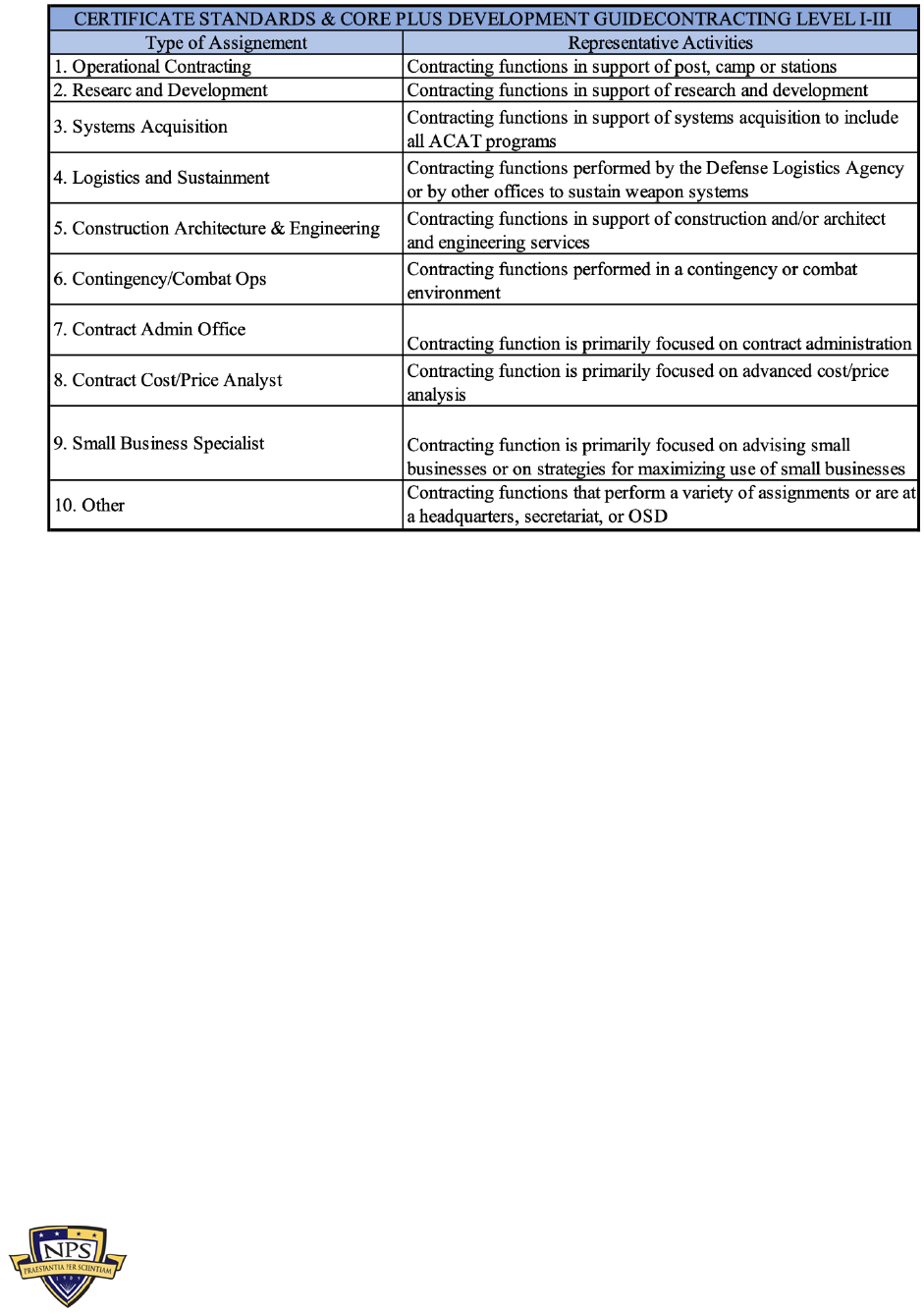

Table 10. DAWIA Contracting Assignment Type Descriptions. Source: DAU

(n.d). ...........................................................................................................64

Table 11. DAWIA Contract Management Core Required Training for

Certification. Source: DAU (n.d.). .............................................................65

Table 12. DAWIA Contract Management Core Plus Recommended Training

for Certification (Level I). Source: DAU (n.d.). ........................................66

Table 13. DAWIA Contract Management Core Plus Recommended Training

for Certification (Level II-III) Cont. Source: DAU (n.d.). .........................67

Table 14. DAWIA Contract Management Unique Position Training

Requirements. Source: DAU (n.d.). ...........................................................67

Table 15. DAWIA Program Management Core and Core Plus Experience

Requirements. Source: DAU (n.d.). ...........................................................71

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management - xii -

Naval Postgraduate School

Table 16. Program Management Statutory Position Requirements. Source:

DON (2019). ..............................................................................................75

Table 17. DAWIA Contracting Experience Requirements. Source: DAU (n.d.). .....78

Table 18. Contracting Statutory Position Requirements Source: DON (2019a) .......82

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management - xiii -

Naval Postgraduate School

LIST OF ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS

1LT/1stLt First Lieutenant

2LT/2ndLt Second Lieutenant

A&S Acquisition and Sustainment

AAC Army Acquisition Corps

AAPC Army Acquisition Professional Course

AC Acquisition Corps

ACAT Acquisition Category

ACC Army Contracting Command

ACE American Council on Education

ACF Acquisition Career Field

AEE Acquisition Entrance Exam

AICC Army Intermediate Contracting Course

AFFAM Air Force Fundamentals of Acquisition Management

AFIT Air Force Institute of Technology

AFOCD Air Force Officer Classification Directory

AFPC Air Force Personnel Center

AFSC Air Force Specialty Code

AL&T Acquisition, Logistics and Technology

ALCP Acquisition Leadership Challenging Programs

AT&L Acquisition, Technology & Logistics

AOC Army Area of Concentration

APDP Acquisition Professional Development Program

AQD Additional Qualification Designation

AQS Acquisition Qualification Standard

AWF Acquisition Workforce

BBP Better Buying Power

BOLC Basic Officer Leadership Course

BQC Basic Qualification Course

BtB Back to Basics

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management - xiv -

Naval Postgraduate School

C&S Command and Staff

CAP Critical Acquisition Position

CAPT/CPT Captain

CCC Captain Career Course

CCLEB Commandants Career-Level Education Board

CCO Contingency Contracting Officer

CDR Commander

CHEK Continuing Hours of Education and Knowledge

CIVINS Civilian Institutions

CL Continuous Learning

CM Contracting Manager

COL/Col Colonel

CPIB Commandants Professional Intermediate-Level Education Board

CRS Congressional Research Service

CSL Centralized Selection List

CTETP Career Field Education and Training Plan

DA Department of the Army

DAC Defense Acquisition Corps

DANTE Defense Activity for Non-Traditional Education Support

DSST DANTE Subject Standardized Tests

DAU Defense Acquisition University

DAW Defense Acquisition Workforce

DAWIA Defense Acquisitions Workforce Improvement Act

DCMA Defense Contract Management Agency

DH Department Head

DIVO Division Officer

DLA Defense Logistics Agency

DoAF Department of Air Force

DoDI Department of Defense Instruction

DoD Department of Defense

DoN Department of Navy

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management - xv -

Naval Postgraduate School

DPM Deputy Program Manager

ENS Ensign

EWI Education with Industry

FA Functional Area

FAR Federal Acquisition Regulation

FIPT Federal Integrated Product Team

GAO Government Accountability Office

GEV Graduate Education Voucher

IDE Intermediate Development Education

IDP Individual Development Plan

ILE Intermediate Level Education

IQC Intermediate Qualification Course

ITP Individual Training Plan

JPME Joint Professional Military Education

JQO Joint Qualified Officer

KLP Key Leadership Position

KO Contracting Officer

LT Lieutenant

LTC/LtCol Lieutenant Colonel

LCDR Lieutenant Commander

LTjg Lieutenant Junior Grade

MAIS Major Automated Information System

MAJ/Maj Major

MBA Master of Business Administration

MCSC Marine Corps System Command

MDAP Major Defense Acquisition Program

MEF Marine Expeditionary Force

MOS Military Occupational Specialty

MRC Mission Ready Contracting

MTL Master Task List

NAVMC Navy Marine Corps

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management - xvi -

Naval Postgraduate School

NAVSUP Naval Supply Systems Command

NDAA National Defense Authorization Act

NOOCS Navy Officer Manpower and Personnel Classifications

NPS Naval Postgraduate School

NWC Naval War College

OCC Office of the Comptroller of the Currency

OJT On-the-Job Training

OP Operational

OPNAV Operational Navy

OSD Office of the Secretary of Defense

PCC Pre-Command Course

PCD Position Category Descriptions

PDE Primary Development Education

PEO Program Executive Officer

PM Program Manager

PME Professional Military Education

PMOS Primary Military Occupational Specialties

PMT Project Management Trainer

PCC Pre-Command Course

PQS Personnel Qualification Standard

QUAL Qualification

RAND Research and Development

RL Restricted Line

SAASS School of Advanced Air and Space Studies

SDE Senior Development Education

SECDEF Secretary of Defense

SOS Squadron Officer School

SSC Senior Service College

TIG Time-in-Grade

TWI Training with Industry

TYCOM Type Commander

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management - xvii -

Naval Postgraduate School

UAOCP Universal Acquisition Officer Career Path

URL Unrestricted Line

USAASC U.S. Army Acquisition Support Center

USACE United States Army Corps of Engineers

USD Under Secretary of Defense

USD(A) Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition

USD(A&S) Under Secretary of Defense of Acquisition and Sustainment

USD(AT&L) Under Secretary of Defense of Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics

USD(R&E) Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management - xviii -

Naval Postgraduate School

THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management -1 -

Naval Postgraduate School

I. INTRODUCTION

Currently, “it is DoD [Department of Defense] policy that the AWF [acquisition

workforce] Program support a professional, agile, and high-performing military and

civilian AWF that meets uniform eligibility criteria, makes smart business decisions, acts

in an ethical manner, and delivers timely and affordable capabilities to the warfighter”

(DoD, 2019, p. 5). The DoD Instruction (DoDI) 5000.66 outlines the Defense Acquisition

Workforce Education, Training, Experience, and Career Development Program, which

originates from the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and

Sustainment (OUSD[A&S]). It is the responsibility of the OUSD(A&S), among other

things, to establish “accession, education, training, and experience requirements for each

acquisition position category based on the level of complexity of each category’s duties”

(DoD, 2019, p. 6). For the DoD, a position is descriptive of an individual’s job.

According to the Defense Acquisition Workforce Position Category Descriptions

(PCD) (2018), there are a total of 15 acquisition position categories. These PCDs provide

duty characteristics that are in line with general acquisition-related responsibilities and

career path specifics. PCDs also include the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency

(OCC) series codes for civilian personnel and a breakdown of DoD component uniformed

personnel’s unique Army Area of Concentration (AOC), Navy Additional Qualification

Designation (AQD), Air Force Specialty Code (AFSC), and Marine Corps Military

Occupational Specialty (MOS). Not every PCD has officers and civilians from each of the

DoD components. Of the 15 acquisition position categories, only five have representatives

from each component: Test & Evaluation, Science & Technology Management,

Information Technology, Program Management, and Contracting. This research focuses

on the program management and contract management career fields. Moving forward,

program managers (PMs) and contracting officers (also referred to as “KOs”) are

referenced as the acquisition workforce, or AWF. This professional project centers on a

Joint perspective, where more than one of the military components (Army, Air Force,

Navy, and Marine Corps) work together on the same program.

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management -2 -

Naval Postgraduate School

The DoD AWF consists of uniformed acquisition officers and defense civilians

employed in multiple areas of expertise. The AWF is “responsible for identifying,

developing, buying, and managing goods and services to support” the needs of the DoD

(Schwartz et al., 2016, p. i). Defense acquisition is a team effort between the PMs and KOs

as they acquire products and provide services on behalf of the warfighter to deliver

capabilities at the right time, to the right place, and within established cost goals. The Better

Buying Power (BBP) 2.0 guidance memorandum states that the factor that has the greatest

impact on effective performance of the Defense Acquisition System is “the capability of

the professionals in our workforce” (Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for

Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics (OUSD[AT&L]), 2013, p. 24). To support the

initiative of establishing higher standards for key leadership positions (KLPs) brought

about by the BBP 2.0, KLP Qualification Boards were established to “certify AWF

personnel as qualified for key leadership positions” (OUSD[AT&L]), 2013, p. 24). The

AWF consists of program management, engineering, contracting, and product support

disciplines engaging in a wide scope of activities throughout the product life cycle

(OUSD[AT&L]), 2013). The life cycle of a product, either supply or service, starts with

the development of the idea behind a need, moves to the development of that idea into a

defined product or service, progresses to the delivery of the supply or service to the end

user, and then concludes with the sustainment of that supply or service until it is no longer

needed (Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment

(OUSD[A&S]), 2020a).

The AWF consists of uniformed enlisted and officer personnel as well as civilians

who work together to support the military (Schwartz et al., 2016). This research focuses on

the field of program management and contract management within the AWF for uniformed

personnel. The PM and KO are the key positions within the program management and

contracting career fields. The efficient support and effective integration of PMs and KOs

are needed for the successful acquisition, sustainment, and delivery of services and other

equipment in response to military requirements. The primary responsibilities for a PM are

to balance the cost, schedule, and performance of a project through its development phase

until the military capability is fully fielded and sustained. Moreover, the PM’s duties

consist of understanding the warfighters’ needs and executing the requirements in a way

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management -3 -

Naval Postgraduate School

that is consistent with DoD guidance and federal regulations. Lastly, the PM ensures that

high quality, affordable, supportable, and effective defense systems, supplies, and services

are delivered expeditiously to the military to support the warfighter. The KO also serves a

vital function in the AWF and works collaboratively with the PM. The primary

responsibility of a KO is to write, administer, and terminate contracts to procure products

and services that satisfy the DoD’s requirements while abiding by federal acquisition

regulations. The KO works closely with the PM, the customer, and technical specialists to

generate explicit requirements packages, develop acquisition strategies, and purchase

capabilities. For the PM and KO to be good at their jobs, the training they receive must

provide the basic skills that will make them successful.

DoD leadership is responsible for providing training, education, experience, and

mentorship to the AWF professionals to support what can be argued as the best-equipped

military in the world. According to the 2020 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA),

the DoD needs to evaluate the state of the AWF capability in areas such as certification,

education, training, experience, and leadership development (Berger et al., 2019). The DoD

mandates PMs and KOs to meet certain certification requirements to qualify to execute the

duties of their positions. Each Service, namely the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine

Corps, in turn, has different training paths and experience requirements for PMs and KOs

to be eligible to hold these positions within the AWF. The AWF must enhance qualification

and certification processes to heighten the performance effectiveness of government

acquisitions and better serve the DoD as a whole.

The DoD relies on the Defense Acquisition University (DAU) to maintain Core

standards under the Defense Acquisition Workforce Improvement Act (DAWIA).

DAWIA, which was passed into law in November 1990, was enacted to improve the

professionalism and effectiveness of the personnel that manages DoD acquisitions by

improving the education, training, and experience levels of acquisition professionals (Navy

Personnel Command, 2019). Specifically, each Service has different timelines for its

officers to reach these training and educational requirements during their careers. It is

important, for the sake of maintaining consistency, for the services to be able to work

together and be able to replace one member of an acquisition team with another, from

another services, when necessary. An Army PM should not have to worry about, for

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management -4 -

Naval Postgraduate School

example, about a Navy KO doing something incorrectly for fear that they will not be as

knowledgeable or experienced as an Army KO. Since each Service has different training

timelines and different requirements, however, currently it can often be difficult for

separate services to work together because of different levels of knowledge and experience.

A. PROBLEM

For major defense acquisition programs (MDAPs) and Joint acquisition programs

in particular, each Service provides representatives on the acquisition team. The differences

in how the services develop and use their uniformed acquisition officers create challenges

for the effective management of large acquisitions, which can span multiple years. PMs

and KOs can rotate out of a program every 2 to 4 years. When a new PM or KO transfers

into a multiyear program and is not as competent as one from a different Service, the

learning during the process can create management inefficiencies that affect the program’s

cost, schedule, and performance baseline. Since each Service has different career path steps

and timelines in training PMs and KOs, the level of competence is not consistent across

the services, and in a Joint program office this may affect the overall efficiency of the DoD

acquisitions. The Joint environment is where all the services come together to work

towards a common goal or idea that is important to more than one Service. An example of

a Joint major MDAP is the Joint Strike Fighter program for next-generation strike aircraft

for the Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force.

As Ashton Carter, the former U.S. Secretary of Defense (SECDEF), stated,

“Today’s security environment is dramatically different and more diverse and complex in

the scope of its challenges than the one we have been engaged with for the last 25 years”

(OUSD[AT&L]), 2016, p. 7). The former SECDEF also stated that leadership needs to

adopt new ways of thinking and performing to develop workforce strategies to close

competency gaps. The nature of requirements is changing due to the transformational

environment and the changing character of warfare and it requires new ways of thinking

and acting (OUSD[AT&L]), 2016).

A 2000 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report, Federal Acquisitions:

Trends, Reforms and Challenges, states that “despite budget surplus, the federal

government continues to face compelling fiscal pressures,” which means “that government

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management -5 -

Naval Postgraduate School

acquisition, a major component of discretionary spending, will have to compete with other

funding priorities for scarce federal resources” (p. 2). Furthermore, a 2019 GAO report

specified that “Congress and the administration face difficult policy choices about federal

revenues, spending and investment; choices that need to be accompanied by a broader

fiscal plan to put the government on a more sustainable long-term fiscal path” (GAO,

2019b, p. 100). These reports highlight that the change in the way the government spends

money and the increase in demand for funding from various sectors is changing the very

nature of how the government allocates funding. With these budgetary demands, it can be

inferred that the services are adjusting to becoming more Joint in nature towards more

combined requirements to optimize budgetary allocations.

B. RESEARCH QUESTIONS

The primary question that guides this research is: “What current career path

practices for PMs and KOs across the services should be adopted from one Service to the

others to maximize competencies and effectiveness in program management and contract

management in Joint acquisition programs?” To answer this primary research question,

there are two secondary research questions that this thesis seeks to answer: “What are the

services’ career paths for active-duty uniformed Acquisition Officers?” and, “Why do the

services have different development timelines for Acquisition Officers?” This research

examines each Service’s career path for PMs and KOs across the certification process,

education requirements, and career milestones.

C. WHY THIS RESEARCH IS IMPORTANT

We opine that symmetry in training education, certifications, and experience for

PMs and KOs across the services will enhance environment outcomes in Joint acquisition

programs. The primary objective of this research is to provide a model career path

framework as a baseline that each Service could consider implementing when developing

PMs and KOs. This approach involves comparing the current career paths for PMs and

KOs in the Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps acquisition fields and then designing

a common career development path that all services could employ. A common career

development path may promote greater efficiency and symmetry within the AWF,

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management -6 -

Naval Postgraduate School

supporting acquisition efficiencies irrespective of military services. More efficient

management of the career path development across the services will benefit the DoD and

allow the services to work together towards desired acquisition program outcomes. A

common career path for PMs and KOs may promote the efficiencies sought by the 2010 to

2015 Better Buying Power initiatives from 2010 to 2015, such as removing “unproductive

processes and bureaucracies for both industry and government” (OUSD[AT&L], 2015, p.

18).

The efficient career path model provided by this thesis suggests potential

improvements to the development of uniformed military acquisition officers within the

services so that, ultimately, the shared knowledge will be synchronized to promote a level

field of competency. The purpose of this research is to compare the career path

development of Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps PMs and KOs to identify

differences in the development of the PMs and KOs. After analysis of the differences, the

research conclude our study by suggesting best practices across all the four services and

recommend a common career path framework for all the services to use that will offer the

best knowledge at each level of an Acquisition Officer’s career.

D. METHODOLOGY

This research relies on several methods for collecting information. The first method

is an extensive literature review of the AWF in the PM and CM career fields. The literature

review consists of various DoD Joint military doctrines, regulation publications, GAO

reports, and prior Naval Postgraduate School (NPS) master’s theses. This literature

examines what research has been done previously and allows the researchers to answer the

study’s research questions. This literature review also allows for comparison of each

Service’s processes and frameworks concerning career field education and training of

uniformed acquisition officers in the PM and KO professions.

Each Service’s processes are compared to identify milestones for career

progression, highlighting the potential benefits in the training and development of

Acquisition Officers. Throughout this process, each Service’s career development process

for acquisition officers is discussed. Next, the certification requirements, education, and

experiences that the DoD requires of acquisition officers within each of the services are

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management -7 -

Naval Postgraduate School

studied. Then, an analysis of how and why the services manage their acquisition officers

differently is performed. Finally, the identification of possible aspects of one Service, that

can be carried across to other services are identified.

E. RESEARCH ROADMAP

This MBA research project is divided into five chapters that examine the uniformed

military Acquisition Officer career path development. The first chapter introduces the

framework, problems, and questions of PMs and KOs of the AWF. The methods in data

collecting to answer the research questions are also indicated in this chapter. The second

chapter consists of background information on the AWF through a literature review of

information on the development of PMs and KOs. The third chapter is devoted to gathering

data from those works of literature. The fourth chapter formulates data and develops

findings to form the best results for the research. The last chapter contains the conclusion

of the findings and a recommendation on a career path for all services to utilize when

developing their PMs and KOs. Also included are recommendations for further research

into this topic.

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management -8 -

Naval Postgraduate School

THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management -9 -

Naval Postgraduate School

II. BACKGROUND

There has been many long-standing, continual, reforms to the DoD’s acquisition

program over the past 50 years (Fox, 2011). Fox (2011) and Allen stated that “the problems

of schedule slippages, cost growth, and shortfalls in technical performance on defense

acquisition programs” have been the basis for many defense acquisition program reforms

from the 1960s to the present (p. vii). According to Layton’s (2007), “major cost overruns,

schedule slippages, and performance shortfalls,” along with “significant problems in

procuring routine and less complex items,” caused the public to have a lack of confidence

in the government procurement process, which led to many reforms in government

procurement policy (p. 7). For instance, in the early 1980s, there were some embarrassing

instances of gross and comical overpayment by the Pentagon for various nonessential

items, such as a $400 hammer or a $600 toilet seat (Ocasio & Bublitz, 2013). President

Ronald Reagan established the Packard Commission in 1986 to decrease inefficiencies in

the defense procurement system. According to the Packard Commission, the fundamental

issues with the acquisition process since 1969 were cost growth, schedule delays, and

performance shortfalls (Fox, 2011). Essential recommendations from this group included

revamping the acquisition process, boosting tests and prototyping, transforming the

organizational culture, upgrading planning, and creating the competitive firm model where

appropriate (Christensen et al., 1999).

In 1969, David Packard, founder of Hewlett Packard, who also served as the Deputy

Secretary for Defense, recognized that a mechanism for the effective management of

defense acquisition and controlling cost was necessary. In 1972, Packard released the DoD

Directive 5000.1 The Defense Acquisition System, which in turn created the DoD

Directive 5000 Series, which governs all aspects of the Defense Acquisition System

(Ferrara, 1996). Packard, in his founding document for the Defense Acquisition System,

stated:

Successful development, production, and deployment of major defense

systems are primarily dependent upon competent people, rational priorities,

and clearly defined responsibilities. Responsibility and authority for the

acquisition of major defense systems shall be decentralized to the maximum

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management -10 -

Naval Postgraduate School

practicable extent consistent with the urgency and importance of each

program. (Ferrara, 1996, p. 111)

Packard also defined a position that would be overall responsible for the execution of

defense systems:

The development and production of a major defense system shall be

managed by a single individual (program manager) who shall have a charter

which provides sufficient authority to accomplish recognized program

objectives. Layers of authority between the program manager and his

Component Head shall be minimum, … [The] assignment and tenure of

program managers shall be a matter of concern to DoD Component Heads

and shall reflect career incentives designed to attract, retain, and reward

competent personnel. (Ferrara, 1996, p. 111)

The intent Packard displayed in this foundational document has, over time, guided

many modifications to the DoD Directive 5000.1, subsequent 5000 Series documents, and

many of today’s defense acquisition statutes, policies, and institutions (Ferrara, 1996). One

of the most significant reforms since Packard created the Defense Acquisition System was

the Defense Acquisition Workforce Improvement Act (DAWIA), which was created

largely in response to continued budgetary restrictions and was passed into law with the

1991 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA; Garcia et al., 1997). The NDAA of

1991, spearheaded by Representative Nicholas Mavroules, established the requirement for

a Defense Acquisition University (DAU), and over time, the DAU has created a premier

training environment. Its curriculum is recognized as the Core standard for all DoD

acquisition professionals, for training requirements (Layton, 2007).

The DAWIA was intended to improve the professionalism and effectiveness of the

personnel who manage DoD acquisitions by enhancing the education, training, and

experience levels of acquisition professionals (Navy Personnel Command, 2019). The

DAWIA was created to “regulate both civilian and military acquisition professionals”

(Ocasio & Bublitz, 2013, p. 5). The act also “provided a new set of opportunities for

documenting the professional development and advancement of the civilian [acquisition]

population” (Ocasio & Bublitz, 2013 p. 5). To incorporate the uniformed acquisition

personnel under the DAU, in 1991, the DoD published DoD Directive 5000.57, Defense

Acquisition University, which stated that the services would provide to the DAU

acquisition personnel training requirements and allocate annual student quotas to the DAU

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management -11 -

Naval Postgraduate School

(Office of the Deputy Secretary of Defense, 1991). As part of the NDAA of 1991, the

Acquisition Corps was formed to regulate, certify, and record the essential and critical

acquisition education, training, and experience of each member across the armed forces.

The creation of the Defense Acquisition System and the changes enacted from the NDAA

of 1991 were a result of changes between how industry and the DoD interacted when it

came to acquisitions (Layton, 2007). During the era of World War II and the Cold War,

from 1939 through 1991, the relationship between government and industry evolved due

to the continued intricate nature and evolution of weapons systems (Layton, 2007).

According to Layton (2007), this evolution changed the government’s role to that of a

program manager who managed teams of contract managers, a role for which the

government was woefully underprepared.

Packard had characterized the DoD AWF as undertrained, underpaid, and

inexperienced. The training and career path management of acquisition personnel were

inadequate, and as a result, Packard called for the creation of a professional acquisition

corps with specific standards, education, training, and experience requirements (Layton,

2007). Layton (2007) further stated that training of government acquisition professionals

was “decentralized, fragmented and often of poor quality” (p. vi), so in response, a

government agency needed to be established to focus on the education and development of

acquisition professionals. The first step in making this effort successful was establishing,

in 1986, the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition (OUSD[A]); (Layton,

2007). This creation was intended to limit the internal government conflicts and improve

the organizational structure of the government’s Acquisition Corps (Layton, 2007). In

1994the USD(A) was redesignated as the Under Secretary of Defense, Acquisition and

Technology (USD[A&T]); the office then transitioned into the OUSD(AT&L) in 2000, at

which time it shifted its focus to an emphasis on life-cycle responsibilities. In 2017, the

OUSD(AT&L) split into two organizations, the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense

for Acquisition and Sustainment (OUSD[A&S]) and the Office of the Under Secretary of

Defense for Research and Engineering (USD[R&E]), where OUSD(A&S) remains the

organizational head of government acquisitions (Mehta, 2017). The DAU, which falls

under the management of the USD(A&S), provides the training for acquisition career field

certification, as well as assignment-specific requirements and executive-level development

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management -12 -

Naval Postgraduate School

for AWF personnel (DoD, 2019). According to the DoD Acquisition Workforce Strategic

Plan FY2016-Y2021, the DAU is “the corporate university for the AWF” which “fosters

professional development for members of the workforce throughout their careers” (DoD,

2016, p. 53). The AWF is comprised primarily of civilian personnel (approximately 91%),

while the uniformed service members make up the remaining 9% of the AWF; however,

the DAU certifications apply to the entirety of the AWF (DoD, 2019). Figure 1, retrieved

from the Human Capital Initiative, which is a part of the OUSD(A&S) shows the current

breakdown of the AWF, between civilian and military, and then further breaks down the

military by Service and acquisition career fields.

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management -13 -

Naval Postgraduate School

Figure 1. Acquisition Workforce Demographics. Adapted from Human

Capital Initiatives (2020).

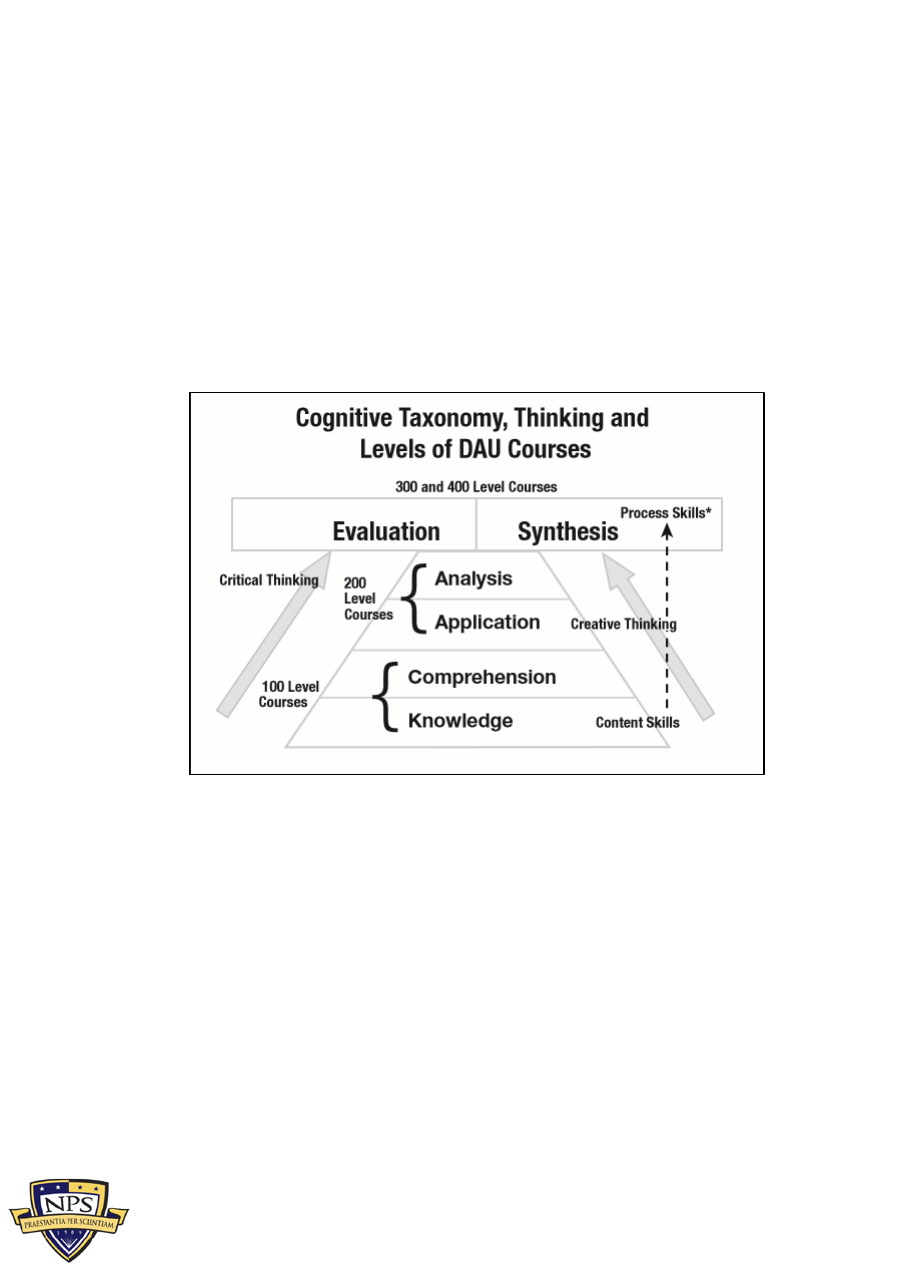

Within the first year of its inception, the DAU tackled the immediate task of

redesigning the curriculum and management of the course development process for the

functional areas (Layton, 2007). According to Layton (2007), DoDI 5000.52, Acquisition

Career Development Program, was used to indicate what courses needed development and

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management -14 -

Naval Postgraduate School

the standards that would be used for certification, as well as to establish the three levels of

certification still used today. The DAU redesigned the courses to ensure maximum

educational effectiveness, which included the use of Bloom’s Taxonomy for the course

development framework. Bloom’s Taxonomy is a hierarchal model that classifies

particular types of learning into categories, each of which has a graduated and increased

degree of complexity (Phillips, 2019). For example, 100-level courses build knowledge

and comprehension, while 200-level courses build application and analysis skills. Together

they create the foundation for critical, creative thinking and team cohesion. Then the 300-

level courses are designed to allow the student to evaluate, synthesize and apply the skills

they learned in the 100- and 200-level courses, sustaining positive performance over time.

This model the DAU used is displayed in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Bloom’s Taxonomy and DAU Courses. Source: Layton (2007).

The DAU’s Level I and Level II courses create a fundamental knowledge in the

functional area and make a specialist out of the acquisition professional, whereas Level III

is the pinnacle of achievement in the curriculum and moves the acquisition professional

from a specialist, who specializes in one area, to a generalist, who is a creative problem-

solver (Layton, 2007). With the continued evolution of certification requirements, instead

of the DoD impractically updating the DoDI 5000.52 annually, the DAU publishes an

annual course catalog, which details the current certification checklists so that members of

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management -15 -

Naval Postgraduate School

the AWF know what to expect for certification in each of the functional areas at each level

of certification (Layton, 2007).

A. PROGRAM MANAGEMENT

The purpose of the Defense Acquisition System is to manage the nation’s

investments, support the services in a timely manner, and acquire capabilities at a fair and

reasonable price (DoD, 2020b). Because it is the PM’s responsibility to “ensure a project

is completed successfully, within budget, on time, and according to the specifications,”

program management is one of the most important functional areas within the DoD’s

acquisition system (Rendon & Snider, 2019, p. 4). For the DoD acquisition system and

acquisition personnel, one main goal is acquiring goods and services to support the

warfighter in defense of the nation. For this purpose, the DAU has developed training

courses that support the development of the program management workforce, consisting

of individuals who support the effective and efficient integration of all functional area

efforts for a successful acquisition (DoD, 2019). Within these training requirements, the

three levels of certification have “assignment types” that guide personnel to the courses

that are required for each level and assignment type. For program management, the

assignment type activities change as the certification levels increase. Appendix A is the

DAU catalog, which gives the training, education, and experience required for certification

of the three levels for program management. Table 1 shows the percentages of the program

management career field within each Service.

Table 1. Uniformed Defense Acquisition Program Management Workforce

by Service

Appendix A describes the DAWIA-specified courses that a PM would need to take

to receive a certification, which is then further broken down by assignment types. The

assignment types separate the type of procurement the PM would be managing, specifically

weapons system, services, or business management systems/information technology. Each

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management -16 -

Naval Postgraduate School

assignment type has representative activities that give task descriptions as examples of

what the PM would be doing in that assignment. Each DAWIA certification level is

assigned courses with training, education, and experience requirements. Each of the three

certification levels has Core Standards courses, which are mandatory, and Core Plus

courses, which are suggested to enhance the knowledge of the PM in that specific area. For

each DAWIA certification level, there are listed training course numbers and titles, and

then each assignment type indicates whether a PM would need to take that specific training

course to receive certification. After each listed training course, at each certification level,

education and experience requirements are listed. The one significant difference between

the certification levels is that at Level III, a PM has to have “at least 24-semester hours

from among accounting, business finance, law, contracts, purchasing, economics,

industrial management, marketing, quantitative methods, and organization and

management” in order to achieve certification (DAU, n.d.). Along with the DAWIA

certification, each service has slightly different definitions of what a PM is and does, as

well as different training and experience requirements for their PMs.

1. Army

The Army identifies its military officer acquisition workforce with the designator

of 51 (U.S. Army Acquisition Support Center [USAASC], 2020). Uniformed PMs in the

Army are designated as 51As and are responsible for the management of a program’s cost

schedule, performance, risk assessment, mitigation, and test and evaluation (USAASC,

2020). Throughout the life cycle of a program, Army PMs manage the efforts and

interaction of the government and industry partners (USAASC, 2020). The uniformed

officers assigned as PMs for the Army are required to maintain current DAWIA

certifications specific to the career field, as well as the type of acquisition assignment, as

depicted in Appendix A (USAASC, 2020). Army uniformed officers apply for the Army

Acquisition Corps as “senior captain [s] or major level [officers] who are branch-

qualified,” and it is recommended that they have at least 24 undergraduate business hours

so that the Army can train and retain the highest quality personnel for the Army Acquisition

Corps (Gambles et al., 2009, p. 26). Once Army officers enter the Acquisition Corps and

are assigned a functional area (51A for PM or 51C for KO) the focused functional training

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management -17 -

Naval Postgraduate School

begins, transitioning them from generalists to specialists (Gambles et al., 2009). Aside from

DAU and DAWIA certifications, uniformed Acquisition Corps officers are required to

maintain a current level professional military development as well as continued learning

points throughout the remainder of their career (Gambles et al., 2009). The Army

additionally has a U.S. Army Acquisition Support Center (USAASC) that provides

individuals with career decision assistance, education on legislative and regulatory

requirements, and awareness (Carroll & Hicks, 2018). Figure 3 is the current Army

Acquisition Corps career path model that the Army recommends all PMs, who are

members of the Army Acquisition Corps, follow.

Figure 3. Army Acquisition Corp Career Timeline. Adapted from DA

(2010).

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management -18 -

Naval Postgraduate School

2. Air Force

The Air Force identifies its program managers as acquisition managers in the

acquisition utilization field, with the AFSC of 63AX (Air Force Personnel Center [AFPC],

2012). For brevity and to maintain consistency, the acquisition managers for the Air Force

are identified as PMs. In the Air Force PMs plan, organize, and direct acquisition

management activities (Department of the Air Force [DoAF], 2012). According to the

Acquisition Managers: Career Field Education and Training Plan publication, PMs

manage acquisition programs, covering every aspect of the acquisition process (DoAF,

2012). PMs also develop, review, coordinate, and execute acquisition plans to support daily

operations, contingencies, and warfighting capabilities (DoAF, 2012). For the Air Force,

the acquisition management career field is a combination of Office of the Secretary of

Defense (OSD) mandated certification training, run by the DAU, and additional Core Plus

recommended training for specific types of assignments that support Air Force continuous

learning requirements (DoAF, 2012). For uniformed PMs, the career path begins at Second

Lieutenant (O-1), but some officers cross over into the career field at Captain (O-3 grade)

after they complete their primary development training (DoAF, 2012). Like the Army, the

DAU courses are the main component of the training for Air Force PMs. However, the Air

Force has the Air Force Institute of Technology (AFIT), which provides courses that earn

DAU equivalencies that meet Level I DAWIA certification requirements (DoAF, 2012).

PMs in the Air Force, for their first assignment to the AWF, are expected to build depth

through technical experience and develop skills as a project manager and acquisition

specialist (DoAF, 2012). Figure 4 is the current AF PM which the AF career path

progression model that all AF 63As follow.

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management -19 -

Naval Postgraduate School

Figure 4. Air Force PM Career Path. Source: DoAF (2012).

3. Navy

Uniformed PMs in the Navy have a designator of AAX, which is called their

additional qualification designator (AQD). The first two alphanumeric characters (AA) of

the AQD are the same for the program management Navy officer at all levels. The third

character (X) indicates assignment responsibility and officer certification level (Navy

Personnel Command, 2020). The Navy is not unique in its PM responsibilities; however,

it is unique in how it identifies the experience for the officer. An officer can hold only one

AAX AQD at a time (i.e., AA2 supersedes AA1). The Navy recognizes officers from the

grades of W-2 to O-9 as being eligible for DAWIA Levels I to III, or AA1, AA2, and AA3.

The qualifications can be held indefinitely by either active or reserve components. The

ability for reservists to hold the qualifications is important for manpower and the filling of

critical billets, because with AWF shortages sometimes there is not an adequate number of

active-duty officers to fill the positions. Once a Navy officer obtains the Level III

certification (AA3), there are opportunities to fill the program management AQD coded

billets of AAC and AAK for critical and key positions, respectively. Officers in the O-4 to

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management -20 -

Naval Postgraduate School

O-9 pay grade are eligible for the AAC qualification, and those in the O-5 to O-9 pay grade

are eligible for the AAK qualification (Navy Personnel Command, 2020). Another qualifier

to fill either the AAC or AAK billets is to have the APM code, which means the individual

is “fully qualified” in the respective career field. The AAC and AAK qualifications are

awarded upon assignment to a billet, whereas AA1 to AA3 are given upon completion of

a given task, such as coursework or experience time.

In the Navy, there is no guarantee that an individual will progress from AA1 to

AAC/K. After all, experience is driven by time in a certain billet, and the billet must be

coded for the PM AQD. To go from AA1 to AAC/K, a Navy officer will have to be

assigned to as many as six billets over 12 years considering the sea-to-shore rotation

schedule and an average tour length of 24 months (Navy Personnel Command, 2019). The

2018 GAO study entitled, Defense Acquisition Workforce: Opportunities exist to improve

practices for developing program manager, recognized that while the Navy does have a

career roadmap and detailed description of skills and competencies needed for the PMs

who supports aircraft, it does not have these tools for PMs who support surface ships

(GAO, 2018). The lack of clear guidance for career field advancement and periodic breaks

in job experience result in either stagnation at a current certification level or prolonged time

to obtain a higher certification level. Figure 5 displays the recommended career path for

the Navy AWF which was recommended from a previous NPS thesis, Modeling the

Department of Navy Acquisition Workforce with System Dynamics written by Joe Everling,

Liz Rosa, Altyn Clark, and David Ford in 2017. The Navy currently does not have an

officially recognized career path for its uniformed acquisition workforce personnel.

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management -21 -

Naval Postgraduate School

Figure 5. Recommended Career Path for Navy AWF. Source: Everling et al.

(2017).

4. Marine Corps

Marines uniquely identify their uniformed personnel with only a four-digit number,

called a military occupational specialty (MOS), and no letters. Uniformed PMs in the

Marine Corps have four MOS designations: 8057, 8058, 8059, and 8061. Warrant Officers

and Limited Duty Officers are assigned only the 8060 MOS and are considered acquisition

specialists in the AWF. The Marines’ designators essentially identify officers’ level of

experience and are only held while in certain positions, called areas of functional expertise

(Marine Corps System Command [MCSC], n.d.-a). The 8057 designation is acquired by

O-1 to O-3 officers and is distinctly named “acquisition professional candidates” to

indicate their positions as “associates” in the project office (Department of the Navy

[DoN], 2015). The MCSC acquisition officer candidates “assist in planning, directing,

coordinating, and supervising specific functional areas that pertain to the acquisition of

equipment or weapons” (MCSC, Acquisition MOS, n.d.). The 8058 MOS is considered the

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management -22 -

Naval Postgraduate School

“acquisition management officer” and the officer must be a Major (O-4) or higher (DoN,

2015). According to Marine Corps System Command “the assignment of MOS 8058

identifies the completion of statutory requirements for acceptance into the Defense

Acquisition Corps (DAC)” (MCSC, n.d.). The 8059 and 8061 MOS designators are the

acquisition management professionals and are assigned to the aviation and ground system

acquisition process respectively (DoN, 2019c). The acquisition management professional

can be as junior as a Major (O-4) select to as senior as a Colonel (O-6). The acquisition

management professional is “accountable for taking requirements from concept

exploration to development of an operational piece of equipment” (MCSC, Acquisition

MOS, n.d.). Figure 6 is the recommended PM career path for uniformed Marine Corps

PMs, retrieved from MCSC.

Figure 6. USMC Acquisition Officer Career Roadmap. Source: Marine

Corps System Command (n.d.-c)

B. CONTRACT MANAGEMENT

Contracting Officers (KOs), who fall within the AWF, work closely with PMs. KOs

are responsible for ensuring the performance of all necessary actions for the effective

execution of contracting actions while also safeguarding the interests of the U.S.

government (Director, Defense Procurement and Acquisition Policy, 2012). The term

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management -23 -

Naval Postgraduate School

contract manager embodies the responsibilities of the contracting officer, and therefore

can be used interchangeably. The contractor and KO are the “two hands that shake” in a

government contract and are the personnel on both sides of the agreement that are

responsible for the successful completion of the contract (Lohier & Johnson, 2019). The

KO, hereafter referred to as CM in this research, manages contracts from conception to

completion and is the primary government official responsible for ensuring compliance

with contractual agreements (Director, Defense Procurement and Acquisition Policy,

2012). The National Contract Management Association (NCMA; 2019) defines contract

management as

The actions of a contract manager to develop solicitations, develop offers,

form contracts, perform contracts, and close contracts. It is a specialized

profession with broad responsibilities that include managing contract

features such as deliverables, deadlines, and contract terms and conditions.

(p. 6)

Currently, and for many years prior, the Government Accountability Office (GAO)

has identified contract management as a high-risk area for the DoD. The DoD obligates

hundreds of billions of dollars annually on contracts for goods and services, roughly two-

thirds of the DoD annual budget (GAO, 2019b). One of the major areas identified as high

risk by the GAO is the AWF specifically AWF personnel’s skill level, because a skilled

AWF is vital to maintaining military readiness and saving the DoD money (GAO, 2019b).

The DAU is responsible for training of contract management personnel, with the individual

Service components providing additional service-specific training. Just as with program

management, the DAU has come up with specific training course requirements to support

the development of CMs. Contract management also currently has three levels of

certification and 10 different assignment types that dictate what courses are required for

certification, which is detailed in Appendix B. Appendix B provides the DAU catalog that

gives the training, education and experience required for certification of the three levels for

contract management. Table 2 shows the percentages of the contract management career

field within each Service.

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management -24 -

Naval Postgraduate School

Table 2. Uniformed Defense Acquisition Contract Management Workforce

by Service

Appendix B contains the contracting core curriculum that covers all three

certification levels, broken down by certification levels and assignment types. Contract

management differs from program management in the assignment types because there are

10 different assignments, though the representative activities do not change across the

certification levels as they do for PMs. Each level for CMs has specified Core courses that

are taught through distance learning or in residence. These required Core Standards courses

are supplemented with Core Plus courses that are designed to deliver assignment type

specific training for each functional area. Each DAWIA certification level for contract

management has different experience requirements, and for education. CMs are required

to hold baccalaureate degrees. However, since the 2020 NDAA was published, the 24-

semester hours in business courses are no longer required for Level I and Level II

certification (NDAA, 2019). As with PMs, the services have slightly different definitions

of what a CM is and does, as well as different training and experience requirements for

their CMs.

1. Army

The Army identifies its military officer acquisition workforce with the designator

of 51 (USAASC, 2020). Contract management in the Army is designated as 51C. KOs

work with the PMs to make determinations on contract awards supporting the acquisition

programs that the PMs manage (USAASC, 2020). KOs can work on acquisitions for the

warfighter, systems, or service contracting and within the Army Corps of Engineers, the

Defense Contract Management Agency (DCMA), the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA),

or at any level of Army operations (USAASC, 2020). Along with a PM, a uniformed

officer’s career as a CM usually begins as a Captain (O3), when officers are selected for

the acquisition branch within the Army (Gambles et al., 2009). Similar to PMs, KOs also

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management -25 -

Naval Postgraduate School

are required to maintain the DAU and DAWIA certifications for the career field, as well as

the type of acquisition assignment they hold (Gambles et al., 2009). Uniformed Army KOs

are also required to concurrently maintain current level professional military development

as well as continued learning points that support their career assignment (Gambles et al.,

2009). Army KOs also have the support of the U.S. Acquisition Support Center (USAASC)

for assistance with career decisions, legislative and regulatory requirements education, and

awareness of the changes within the AWF (Carroll et al., 2018). Figure 7 is the current

Army Acquisition Corps career path model, that the Army recommends all CMs, who are

part of the Army Acquisition Corps, follow.

Figure 7. Army Acquisition Corp Career Timeline. Adapted from DA

(2010).

2. Air Force

The Air Force identifies its contracting uniformed personnel as “contracting” in the

“contracting utilization field” and with the AFSC of 64PX (AFPC, 2012). Within this

research, for brevity and to maintain consistency, the contracting uniformed personnel for

the Air Force are identified as contracting managers (CMs). The Air Force trains its

uniformed acquisition officers beginning when they initially commission, specializing

them in their functional discipline. This is one of the main differences between the Air

Force and the other services (DoAF, 2014, p. 41). The Air Force creates technical

Acquisition Research Program

Graduate School of Defense Management -26 -

Naval Postgraduate School

specialists, where the other services create generalists before transitioning them to

specialists later in their careers. In the contract management field, from Second Lieutenant

(O-1) to Colonel (O-6), uniformed acquisition officers are submerged in the AWF from

day one. The Air Force has its uniformed AWF personnel complete the DAU’s required

certifications, which are required for acquisition professionals by DAWIA, but it also