1

The Use of Standardized Testing in Admissions:

Summary of Key Findings

April 2024

Introduction

In April 2020, Cornell suspended the requirement for SAT/ACT exam

scores for undergraduate applications for admission. This was largely a

response to the logistical difficulties accessing testing locations with the

onset of the COVID pandemic, but the decision also eased some concerns

that the flaws that inhere in standardized tests undermine some of

Cornell’s admissions goals.

As shown in Table 1, four of the undergraduate colleges adopted “score-

free” policies (where test scores that have been provided to Cornell by the

testing agencies are not uploaded into the admissions data reviewing

system

1

), and the remaining colleges have “test-optional” policies (where

official test scores are easily available to the reader and may inform the

admission decision).

In the spring semester of 2023—following two cycles of fall first year

admissions—the Provost charged a Task Force on Testing in Admissions

to look at the impact of removing the testing requirement by considering

the following questions:

• Does the submission of test scores alter admission chances in the test-optional

colleges?

• Do test-optional or score-free admissions policies impact the socioeconomic or

racial/ethnic composition of admitted students?

• Is there evidence that the use of test scores enhances student outcomes at

Cornell?

The Task Force delivered a confidential report in May 2023 that

summarized findings relating to the matriculating cohorts of Fall 2021 and

Fall 2022.

1

If an applicant self-reports scores on the Common Application, those scores are viewable through a PDF

of the application materials in both “score-free” and “test-optional” colleges. In the score-free colleges,

reviewers are asked not to consider those scores.

2

At the request of the Provost, these analyses were updated in the spring of

2024 by the office of Institutional Research & Planning. The updated

findings, described below, reinforce and extend the more tentative

conclusions from the earlier report.

Notable findings from both rounds of analyses include:

• There is not a clear indication that the relaxation of the testing

requirement has increased the diversity of matriculating first year

students.

• In Cornell’s “test optional” colleges (where applicants test scores

can be considered in the review process), the submission of test

scores has a substantial and statistically significant impact on the

chances of being admitted.

• Students admitted with known test scores had better academic

outcomes than students who were admitted without test scores.

Opting to provide test scores

Official test scores are provided to Cornell by the testing provider at an

applicant’s request.

2

As shown in Table 1, a minority of applicants had a

test score sent to Cornell. In Fall 2023, just 24% of Cornell’s undergraduate

applicants provided an official score.

Table 1. Percentage of Fall freshman applicants submitting an SAT or ACT score

Applicants Acceptances Enrolls

Test

policy

College

Fall

2021

Fall

2022

Fall

2023

Fall

2021

Fall

2022

Fall

2023

Fall

2021

Fall

2022

Fall

2023

Test

optional

A&S

31%

28%

24%

53%

52%

50%

67%

63%

62%

Engineering

35%

34%

30%

57%

64%

61%

71%

77%

75%

CHE

42%

33%

28%

52%

53%

45%

65%

63%

54%

ILR

32%

28%

23%

69%

43%

43%

74%

47%

46%

Brooks

3

23%

43%

53%

Score free

CALS

29%

24%

20%

38%

23%

21%

39%

24%

22%

AAP

26%

22%

18%

39%

26%

17%

40%

26%

17%

JCB-Dyson

27%

19%

12%

39%

18%

11%

40%

18%

11%

JCB-Nolan

22%

18%

18%

30%

21%

20%

30%

21%

18%

Total

University

31%

28%

24%

50%

44%

42%

59%

50%

48%

2

The request to have test scores sent to an institution may occur well before submitting a college

application, such at the time of taking the test. This may explain why some students had their scores sent

even when they [later?] applied to one of the score-free colleges.

3

The Brooks School of Public Policy became an admitting unit during the period of interest.

3

While Cornell did not receive test scores from most applicants, data from

the Fall 2022 administration of Cornell’s New Student Survey

4

indicate that

91% of matriculating first-years took either or both the SAT and/or the

ACT. Indeed, 70% had taken the SAT (or the ACT) test multiple times.

When test scores are an optional part of the admissions process, the

decision to provide a test score is a question of strategy.

5

Presumably,

many applicants guessed that providing their scores would hurt their

chances of admissions. Indeed, self-reports of test scores on the survey

indicate that those who did not submit their SAT scores to Cornell tended

to score lower than those who did (see Figure 1). Notably, it appears that

some applicants with perfect and near perfect scores did not submit them.

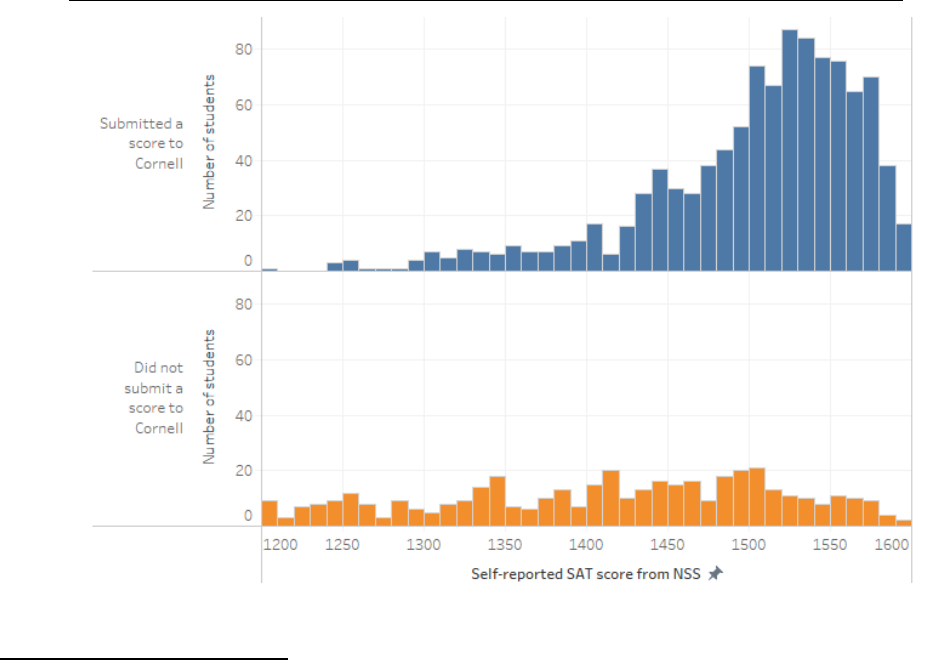

Figure 1. Self-reported SAT scores of Fall 2022 New Student Survey respondents, by whether scores were

submitted to Cornell by the test agencies

4

This survey of first-year students had a 79% response rate and ask students how many times, if any,

they had taken the SAT and the ACT. It also asked students to self-report their scores. The comparison of

self-reported test scores with official test scores when possible indicates that the score self-reports are

accurate.

5

In test-optional colleges, there has not been a way for the applicant to have test information suppressed

on the application if it has been provided to Cornell already. Thus, it is possible that some applicants

provided test scores to Cornell somewhat unintentionally.

4

Whether it is “strategic” to submit a score with one’s application may not

be immediately apparent to high school students: teenagers with

differential access to the resources that may help them navigate the

question to their best advantage.

Data from the 2022 New Student Survey suggest that students’ decisions to

share test scores are shaped by social background factors such as the type

of high schools they attended, their family incomes, and their access to

and use of guidance counselors. Among students who scored above 1400

on the SAT, for example, Black students were less likely than White and

Asian students to have submitted their test scores: 62% of Black students

versus 74% of White students and 79% of Asian students with these high

scores sent them to Cornell.

To the extent that students from different kinds of backgrounds are

differentially deciding to withhold scores that are strong enough to help

them gain admission to Cornell, test-optional policies may undermine

equity in admissions.

Access

Because standardized test scores are systematically correlated with

indicators of privilege, some have anticipated that removing the test

requirement could facilitate access for applicants who are low income;

Black, Hispanic, and/or Indigenous; and those who are the first in their

family to attend college.

Others have argued that test scores read in context can buttress the case

for admission among applicants who may not have the clear signals of

strong application (such as coming from a known and well-regarded high

school, informative letters of recommendation, and AP exams). Read with

an appreciation for context, an applicant with a test score that may be

below the average for Cornell students but that is well above average for

their high school may be considered a desirable admit. Test scores enable

those types of decisions.

On the whole, it does not appear that the shift in Cornell’s testing policy

has played a major role in diversifying first year students by

race/ethnicity/citizenship, first generation status, or family income (see

Figure 2). While there are some very modest shifts between the Fall 2020

5

cohort (that submitted required test scores) and the cohorts that followed

(that did not), the movement towards increasing representation of less

advantaged groups has been in process for several years. For example. the

percentage of first year students who are Black, Hispanic and/or

Indigenous (BHI) increased from 23% to 27% in the five years preceding

the pandemic. In Fall 2021, that percentage increased further to 28%, but

has declined very slightly to 25% in Fall 2023.

Perhaps the strongest evidence of a shift is with respect to first generation

status (see middle panel of Figure 2) where the percentage of the class that

is first generation increased from 16% to 19% between 2020 and 2021 and

has remained at that level in the subsequent matriculating cohorts.

However, the proportion of the class that is first generation had been

increasing prior to the policy shift as well, so too this could be considered

as a piece of a broader trend.

If the policy shift away from testing has substantially enhanced access to

Cornell, it has done so in ways that elude simple measurements.

Figure 2. Composition of first-time first-year students by matriculation semester: race/ethnicity/citizenship,

6

first

generation college student, and financial aid status

6

Students who identify as Black, Hispanic, and/or Indigenous are grouped here as “BHI.”

6

Chance of admission

As shown in Table 1 above, less than a third of applicants submitted test

scores since the test requirement was removed. However, more than 40%

of our acceptances and about half of matriculating freshmen had provided

scores.

This difference could reflect the fact that, on balance, students who submit

test scores are stronger applicants on other dimensions. That is, they

might have stronger academic records in high school, stronger letters of

recommendation and so forth.

In test-optional colleges—where the difference between applicant and

admit submission rates is much larger—it could also result from

admissions officers being more likely to admit students when the officers

could see the test scores.

Regression models that estimate the probability of admission holding

constant several other factors—including high school GPA and additional

student and high school characteristics—suggest that submitting test

scores significantly increases the likelihood of admission in the test-

optional colleges but has little or no effect in the score free colleges.

The differential impact under the two policy scenarios suggests that

admissions officers are using the test scores to inform decisions when they

are available. Given this finding, it seems prudent for those applying

under the test-optional policy to send in their test scores.

Academic outcomes

Previous studies at Cornell and elsewhere have found that SAT scores are

significant predictors of first-year GPAs.

The vast majority of students who have matriculated at Cornell—with or

without known test scores—have performed well here. However, those

who were admitted without test scores tended to have somewhat weaker

semester GPAs, were more likely to fall out of “good academic standing,”

7

7

To maintain good academic standing, a student must successfully complete at least 12 academic credits

and have a GPA of at least 2.0 each semester.

7

and were less likely to re-enroll semester after semester. These patterns

hold true holding constant students’ high school GPAs as well as other

personal and high school attributes.

There is no evidence that these differences have diminished across cohorts

of matriculants; the gap in first semester GPA has remained consistent for

all three years of new admits.

The association with GPA may be attenuating somewhat as students

accumulate more semesters of experience at the university. That is, is the

gap is smaller in the third semester than it is after the first semester. This

is encouraging for those students who have persisted, but the robust

evidence of increased rates of academic struggle and attrition remains a

concern.

The analyses of outcomes are consistent in suggesting that when

admissions officers have test scores available to them as additional

information in a holistic admissions process, they are able to use them in a

way that supports positive outcomes for Cornell students.

2023 Task Force Members

• Marin Clarkberg, Chair & Associate Vice Provost of Institutional

Research & Planning

• Jon Burdick, Vice Provost for Enrollment

• Scott Campbell, Director of Admissions in the College of Engineering

• Jason Kahabka, Associate Dean for Administration in the Graduate

School

• Alan Mathios, Professor in Public Policy and Economics

• Lisa Nishii, Vice Provost for Undergraduate Education and Professor

of Human Resource Studies

• David Shmoys, Professor of Operations Research and Information

Engineering

• Michelle Smith, Senior Associate Dean for Undergraduate Education

in the College of Arts & Sciences and Professor of Ecology &

Evolutionary Biology