December 2013

National Endowment for the Arts

1100 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW

Washington, DC 20506

Telephone: 202-682-5400

arts.gov

Sunil Iyengar, Director

Other staff contributors: Steven Shewfelt and Tamika Shingler

Wassall of Northeastern University for his valuable assistance while this document

was in production.

202-682-5496 Voice/TTY

(a device for individuals who are deaf or hearing impaired)

Individuals who do not use conventional print materials may contact the Arts

an alternate format.

This publication is available free of charge in PDF format at arts.gov, the website of

the National Endowment for the Arts.

Preface ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������v

PART I: Accounting for the Nation’s Arts and Cultural Industries: Why, What, and How? ������������ 1

Section 1� Why a Satellite Account on Arts and Culture? ���������������������������������������������������������������������� 1

Section 2� What Does the ACPSA Measure? ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 3

Section 3� How Were the ACPSA Commodities and Industries Selected? ������������������������������������������ 9

Table 3� Commodities Included in the ACPSA ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 15

Section 4� Future ACPSA Products and Frequently Asked Questions ����������������������������������������������� 18

FAQs ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 20

PART II: Accounting for the Nation’s Arts and Cultural Workforce �������������������������������������������������� 22

Section 1� Adding Value to the Satellite Account: A New Taxonomy for Arts and Cultural

Occupations ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 22

Section 2� Locating All Occupations (Arts and Non-Arts) Within Arts and Cultural Industries �� 31

Section 3� Computing the Monetary Value of Arts and Cultural Volunteers ������������������������������������ 34

List of Tables Accompanying Part II and Online ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 37

Acknowledgements ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 38

APPENDIX A� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 39

Understanding Industry Classications ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 39

APPENDIX B� ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 40

Illustration of the Standard Occupation Classication System ����������������������������������������������������������� 40

References and Further Reading ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 42

In 2012, the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) and the U.S. Department of Commerce’s

Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) agreed to devise a system for valuing arts and culture as a

distinct sector of the nation’s economy.

Thereafter, in consultation with the NEA, the BEA made arrangements to track a cohort of arts

and cultural commodities and industries and compute their annual impact on gross domestic

(ACPSA), preliminary estimates from which are being released with this guide.

taken steps to account for arts and cultural contributions more comprehensively.

In the spring of 2013, the BEA announced that it would begin to consider spending on

recordings, commercial stock photography, and greeting card designs) as capital assets rather

(This revision occurred outside the ACPSA development process, and while the result is not

Other countries also have shown the way. Economists in the UK, Canada, Australia, Spain,

and Colombia, to name a few examples, have proposed or established arts-related satellite

accounts for their countries—whether the organizing principle is creative production,

cultural activity, or some hybrid of both concepts.

Analysis has taken every opportunity to avail of these resources. This white paper is partly

an attempt to repay the debt, by taking the reader through the U.S. process for assigning

economic value to industries and commodities.

information it ultimately will provide, how the BEA and NEA tackled complex issues of

Midway through work on the satellite account, however, the NEA’s research staff decided that

the white paper could serve a second purpose. In conversations with multiple stakeholders

about the ACPSA project, there frequently arose confusion—or, at any rate, unanswered

questions—about how the choice of arts and cultural commodities might bear on future

recognition of arts/cultural workers (and not just industries) as a critical component of

economic value.

This line of inquiry led NEA researchers to advance a new taxonomy of arts and cultural

occupations, to supplement use of the commodities that appear in the satellite account. This

list stems from an evaluation of Bureau of Labor Statistics occupation codes, but it allows

for individual and combined estimates of economic value—which, again, may be examined

v

Another method presented here is more empirical. Instead of a top-down approach for

determining which occupations merit inclusion in an arts/cultural workforce taxonomy,

this method consists of analyzing the presence of all types of occupation within arts and

represented within each industry.

blueprint for building a comparable robustness in the methodology used to track arts

and cultural occupations at the U.S. level. Likewise, a section on capturing the economic

value of the nation’s arts/cultural volunteers supports the NEA’s long-term aim of more

comprehensive accounting for this sector.

Economic outcomes from the arts fall into one domain of impacts under investigation by

the NEA seeks to “advance public knowledge about the arts’ contributions to American life.”

Other research projects bid to achieve the following goals: to quantify audience members’

levels of engagement with NEA-funded arts programming; to track the long-term

relationship between the arts and livability in communities throughout the nation; evaluate

the effects of creative arts therapies in military personnel experiencing psychological

illnesses and mild traumatic brain injury; and to address knowledge gaps concerning the

arts’ link to human development at every stage of the lifespan. For many of these studies,

the NEA is collaborating with one or more federal agencies to realize a shared objective.

Finally, the length of this paper and the variegated ground it attempts to cover are

testimony to the wide-ranging ambition behind satellite accounts in general. As the BEA

sectors that are treated more summarily in the main industry accounts. As the NEA

embarks on the second year of this experiment with the BEA, we hope this white paper will

illumine the factors and choices that informed the account’s creation, even while we know

that there will be ample scope for improvement in the months ahead.

Sunil Iyengar

National Endowment for the Arts

vi

1

The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA),

nestled within the U.S. Department of

Commerce, produces a system of accounts

that measure what the U.S. economy

produces, how much is earned by that

production, and how earnings are spent.

The BEA’s national income and product

accounts (NIPAs) include gross domestic

product

value of the goods and services produced in

the United States over a given period—and

personal consumption expenditures

(PCE), which make up 70 percent of the total

Complementing the NIPAs are the BEA’s

industry accounts, which provide a

framework to measure and analyze, by

industry, the production of goods and

services. These accounts depict the internal

workings of the U.S. economy.

The BEA releases industry accounts in

industry accounts, which report estimates

for 65 industries, and the second are the

“benchmark” industry accounts, which are

for 425 detailed industries. For example, the

BEA’s annual industry accounts show that

the performing arts, spectator sports, and

museums, combined, added $83 billion to

the U.S. economy in 2011. The more detailed

benchmark accounts, by contrast, reveal that

the performing arts, as distinct from sports

and museum industries, contributed $7.2

Despite the wealth of information available

from the BEA’s industry accounts, they

do not visibly capture every aspect of the

economy. Satellite accounts, alternatively,

expand the capacity of the national

accounting system. Linked to, but distinct

from, the main industry system, they cut

across sectors and arrange industry data

to show detail without overburdening the

main industry accounts. Because they are

supplemental, satellite accounts also permit

conceptual development—in effect, they

can serve as laboratories for economic

accounting.

The BEA, for example, produces a satellite

account on travel and tourism (the Travel

and Tourism Satellite Account, or TTSA)

1

.

Travel and tourism services are provided,

in either large or small part, by a variety

of industries spanning accommodation,

transportation, entertainment, and retail

sales. Consequently, the value of travel and

tourism is not evident in the main system of

accounts.

To illustrate: the BEA estimates that 75

percent of the services provided by the

accommodations industry (e.g., hotels and

percent of gas-station sales stem from

1 In addition to the TTSA, the BEA has

produced a satellite account on transportation

(last updated in May 2000) and is in the midst of

producing a satellite account on healthcare. For more

literature on these accounts.

2

travel and tourism. The TTSA teases out the

portion of each relevant industry’s travel

and tourism production to arrive at a total

for the sector—in 2011, travel and tourism

added $415 billion to the U.S. economy.

A Satellite Account on Arts and Cultural

Production

Arts and cultural production is included in

accounts. However, economic contributions

for the production of arts and cultural goods

and services, therefore, the NEA and the

BEA agreed to develop an Arts and Cultural

Production Satellite Account (ACPSA).

This account will ensure, for example,

that estimates for the performing arts are

reported not only in aggregate, but also for

troupes, and symphony orchestras.

Moreover, there are a number of industries

whose production is only partly related to

arts and culture. To include the entire

amounts produced by these industries

the arts and culture, while excluding the

industries in their entirety would result in

underestimation.

To rectify this matter, the ACPSA, like the

TTSA, includes only the share of production

related to the arts. For example, the ACPSA

includes only the percentage of software

publishing related to computer games,

computer-assisted design (CAD), and other

arts-related software. Similarly, entries for

computer design systems (a professional

services industry) are restricted to

production supporting the motion picture

and sound recording industries. The ACPSA

also includes fractional production by

advertising services, educational services

(e.g., colleges and universities), and printing,

to name a few.

As a satellite account, the ACPSA has the

arts and cultural production in the U.S.,

providing an unprecedented amount of

detail about the economic value created by

this sector.

3

Before addressing the commodities and

industries captured by the ACPSA, it is

helpful to understand some of the inner

workings of the account. This section

summarizes the data sources used to

generate the account. It introduces the

concept of “I-O” tables and their resulting

measures such as consumption and

value added, which are part of the BEA’s

framework for measuring economic activity.

At the time of producing this white paper, the

NEA did not have access to the 2013 ACPSA,

examples shown below, consequently, draw

recording industries reported in the BEA’s

most recent 2011 annual industry accounts.

Data Sources

The BEA uses a wide range of data sources

and methods to prepare the National

Income and Product Accounts (NIPAs) and

industry estimates. Data produced by the

U.S. Census Bureau and the U.S. Bureau of

Labor Statistics are key data sources, as are

government administrative data such as tax

returns.

Because they do not interfere with the BEA’s

main industry estimates, satellite accounts

can also draw from less conventional data

sources, including data collected by private

industry.

Below is a partial summary of data sources

the BEA used or accessed in preparing the

ACPSA:

Data from the U.S. Census Bureau

Economic Census; Services Annual Survey

(SAS); Non-Employer Statistics; Census of

Governments

Among the most important data sources

used by the BEA is the Economic Census,

which is conducted by the U.S. Census

Bureau in years ending in “2” and “7.”

The Economic Census provides the most

comprehensive data available in terms of

industry coverage and in the measurement

of the economic units in those industries.

the BEA also draws from the Census Bureau’s

annual surveys of business establishments.

The Service Annual Survey (SAS) is sent to

72,000 service businesses (both taxable and

tax-exempt) with paid employees. Many of

the industries included in the ACPSA are

service industries, including motion picture

and sound recording, publishing, designer

services, and the performing arts.

Workers in a number of arts and cultural

occupations, however, report high rates of

self-employment. For example, 68 percent of

writers and authors are self-employed, as are

60 percent of photographers, art directors,

and craft artists.

The ACPSA measures the production and

earnings of the self-employed through the

Census Bureau’s non-employer statistics,

which are based, in turn, on Schedule

C applies to the self-employed if the primary

purpose of the work is to generate income or

criteria are met, Schedule C attachments

are required of self-employed workers with

business income of $400 over and above

expenses.

The ACPSA also includes arts and cultural

production by government, including

government-operated libraries and

museums. Source data for these estimates

like the Economic Census, is conducted by

ending in “2” and “7.”

4

Data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

and the U.S. Department of Labor

Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages;

Consumer Expenditure Survey; LM2 Reports

The Quarterly Census of Employment

and Wages (QCEW) program produces a

comprehensive tabulation of employment

and wage information for workers covered

by unemployment insurance programs.

2

The QCEW program publishes employment

and wage data down to the six-digit NAICS

industry level, if disclosure restrictions are

met.

Conducted by the Census Bureau for the

BLS is the Consumer Expenditure Survey

(CES), which consists of interview and

diary components. The CES is the only

federal survey to provide information on the

complete range of consumers’ expenditures

and incomes.

The ACPSA includes estimates for arts-

related unions such as organizations

representing stage and screen actors. Labor

organizations with $250,000 or more in

Standards within the Department of Labor.

Data from Non-Government Sources

The ACPSA also draws on non-government

source data. For example, the ACPSA

includes the construction of educational and

recreational buildings such as libraries and

museums. These estimates were derived,

As another example, detail within the

architectural services industry was

estimated using the Work-on-the-Boards

2 Excluded from the QCEW are members of

the armed forces, the self-employed, proprietors,

domestic workers, unpaid family workers,

and railroad workers covered by the railroad

unemployment insurance system.

Survey and Panel, which is conducted by the

American Institute of Architects’ Economics

NAICS Codes

Central to the workings of the ACPSA is the

System (NAICS), a two- through six-digit

groups business establishments (page 39)

into industries according to similarity in the

process used to produce goods and services.

As explained by the U.S. Census Bureau, each

digit in the NAICS code is part of a series of

progressively narrower categories: more

detail.

3

and incorporated into the BEA’s industry

iteration of the ACPSA is measured using

wave of the account (planned for release in

accounts to more accurately portray the

dynamic U.S. economy and permit better

international comparisons with economic

data from other countries. For example, the

ACPSA includes “Internet publishing and

broadcasting” among its arts and cultural

better accounted for this industry than

which combined Internet publishing and

broadcasting with other industries, such as

newspapers and periodicals.

Appendix A illustrates the NAICS hierarchy

for performing arts industries.

The Inner Workings of the ACPSA: I-O

Accounts

While it is beyond the scope of this

document to attempt to fully explain the

3 Please see Appendix A for an illustration of

the NAICS hierarchy.

5

BEA’s methods of calculating national

income and product accounts (NIPA) and

industry estimates, this section draws on

the agency’s annual industry accounts to

highlight the ACPSA’s inner workers through

“input-output” (I-O) accounts.

4

As a satellite account, the ACPSA expands

on the BEA’s main industry accounts, which,

in turn, consist of the “input-output” (I-

and services among industries in the

production process.

5

I-O accounts, as the

BEA explains, show the interdependence

among the producers and the consumers in

the U.S. economy. Two main tables in the I-O

accounts are the standard “make” and “use”

tables.

The standard make table shows the value

of commodities (e.g., goods, merchandise,

or services) produced by each industry in a

given year. For example, virtually all motion

picture and sound recording merchandise

and services are produced by motion picture

and sound recording industries (NAICS

512)—$102.7 billion in 2011.

6

The standard use table, alternatively, is a

matrix showing the use of commodities by

industries as “intermediate inputs” and by

the BEA’s methods of calculating NIPAs and industry

estimates should refer to the bureau’s technical

documentation, shown in the references section of

this document.

5 Because the I-O accounts drive the BEA’s

industry estimates, I-O accounts are also released on

most recent annual I-O accounts report estimates for

2011, while the current benchmark I-O accounts are

shown for 2002.

6 The BEA’s make table reports that computer

systems design industries and miscellaneous

industries produced $481 million and $156 million,

respectively, in motion picture and sound recording

commodities in 2011.

Intermediate and Final Uses

Of the $102.9 billion in motion picture and

sound recording commodities produced in

2011, roughly 60 percent were purchased

as intermediate inputs—i.e., the goods and

services that are used in the production

process to produce other goods and

services.

The remaining 40 percent of motion picture

and sound recording merchandise and

users,” composed of: U.S. consumers, who

U.S. businesses; and foreign purchasers

(exports). In 2011, U.S. consumers

purchased $36 billion in motion picture

and sound recording merchandise and

purchases. An additional $11.1 billion was

exported to foreign purchasers, while the

U.S. imported $5.2 million.

Change in private inventories shows that,

in 2011, $156 million more in motion

picture and sound recording merchandise

and services was sold than produced—

businesses drew down their inventories.

Selling more than what was produced in a

given period, a year in this case, is a sign

that motion picture and sound recording

industries may step up production in the

next year.

6

Because BEA’s 2011 annual tables were

produced prior to the 2013 revisions to

the national accounts, they do not capture

artistic originals (e.g., movies and music

recordings) as investments.

7

Consequently,

for motion picture and sound recording

commodities.

Key Measures of Arts and Cultural

Production

Industry Output and Value Added

Two key measures provided by the ACPSA

are “industry output,” and its closely related

measure, “value added.”

8

Industry output is

the market value of the goods and services

produced by an industry. Value added,

alternatively, is gross domestic product by

industry.

7 See the text box on artistic originals in Part I,

Section 4.

8 In the BEA’s annual industry accounts,

“industry output” is referred to as “gross output.”

Industry output includes sales or receipts

and other operating income, commodity

taxes (e.g., sales and property taxes), and

inventory change.

9

Value added is industry

output minus intermediate inputs (i.e.,

and purchased services)—i.e., value added

is the industry’s contribution to the national

In 2011, industry output for motion picture

and sound recording industries was $103.6

goods and services used by motion pictures

and sound recording, but not produced by

9 Inventory change is the difference between

last year’s ending inventory and the current year’s

inventory.

The ACPSA measures arts and cultural producon by business establishments. The U.S.

Census Bureau denes a business establishment as a single physical locaon where business

is conducted or where services or industrial operaons are performed. An enterprise, on the

other hand, may consist of more than one locaon performing the same or dierent types

of economic acvies.

As an illustraon, the Madison Square Garden Company is a sports, media, and

entertainment enterprise. Madison Square Garden establishments include Radio City Music

Hall (home to the Rockees), the Beacon Theater, the Chicago Theatre, the Forum, and

the Madison Square Garden Arena. Each of these establishments falls into NAICS 71131,

“promoters of performing arts, sports, and similar events, with facilies,” which is “parally”

in scope of the ACPSA. (In other words, the ACPSA restricts producon from this industry to

the performing arts.)

The Madison Square Garden Company also owns and operates Fuse, a music television

network within broadcasng, which is another industry captured by the ACPSA.

Industry Output

Value Added

7

(Millions of dollars)

Uses:

$61,167

$41,771

Personal consumpon expenditures $36,014

Change in private inventories –$156

Private xed investment —

Exports $11,098

Imports –$5,185

Source: 2011 Use Table, U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis

their own labor and capital. The electricity

used by the industry was generated by the

energy sector. Camera and sound-recording

equipment and set lighting were made by

the manufacturing sector.

Subtracting these kinds of intermediate

costs from industry output yields $60.2

billion in value added by motion picture and

sound recording industries. In other words,

using their own labor and capital, motion

picture and sound recording industries

2011.

10

10 Due to disclosure controls, industry

output and value added reported in the ACPSA

are aggregated. For example, industry output and

value added by motion picture and sound recording

industries are subsumed within the ACPSA’s industry

aggregate titled “information, electronic.” However,

industry output and value added for motion pucture

and sound recording industries can be calculated

by combining data from the ACPSA with estimates

reported in the Economic Census. For more

information, go online to see the NEA’s arts data

Employment, Compensation, and Measures of

Indirect Production

As part of the ACPSA, the BEA also

estimates arts and cultural employment

and employment compensation. In 2011,

for example, motion pictures and sound

recording industries staffed 371,000

(full- and part-time) employees; their

compensation totaled $28.9 billion.

11

The ACPSA also includes estimates of

“direct” and “total” output, as well as “total

commodity output multipliers.” While an

in-depth discussion of these measures

is beyond the scope of this document, it

is worth noting simply that measures of

direct and indirect output derive from I-O

requirements tables.

11 Compensation of employees consists of

wages and salaries in cash; wages and salaries in

kind (e.g., transit subsidies); and supplements to

wages and salaries such as employer contributions to

pension, health, and unemployment insurance funds.

The BEA’s structure for measuring employment

differs from that used by the BLS’s OES program,

which is the subject of Part II of this document. For

example, employment measured by the BEA includes

self-employed workers, but it excludes estimates by

occupation. Please see Part II of this document for

more information.

8

The BEA reports direct and total

requirements (the sum of direct and

for a commodity increases, there will be

an increase in output of that commodity—

sometimes called the direct effect. As

producers of this commodity increase their

production, there will also be an increase in

the output of their suppliers—the indirect

effect.

To illustrate direct and total requirements,

assume that U.S. consumers (a component

for motion picture and sound recording

merchandise and services by $1. In

response, as reported in the BEA’s 2011

industry requirements table, motion picture

and sound recording industries increase

their output by $1.14.

But as motion picture and sound recording

industries increase output, their suppliers

must increase their production as well.

For example, the $1 increase in consumer

demand for motion picture and sound

recording merchandise and services leads to

a $0.11 increase in output by “miscellaneous

services” (e.g. electronic communication

services, appraisal services), and nearly

$0.02 in production by the legal services

industry. The $1 increase in demand

cascades through many industries, reaching

$1.71 in “total industry output requirement.”

Because moon picture and sound

recording industries are predominantly

for-prot and therefore taxable, measuring

their industry output and value added can

be accurately measured using revenue or

sales. However, relying solely on revenue

may understate the value of nonprot

tax-exempt business establishments. These

instuons typically oer discounted or

free services not captured by revenue or

sales.

Consequently, the ACPSA draws on

expenditures in addion to revenue to

measure industry output and value added

for educaonal services such as ne arts

schools, performing arts companies,

museums and historical sites, grant-

making services, and business and labor

organizaons such as unions.

9

The selection of commodities (i.e., goods and

services) for the ACPSA, and, consequently,

the selection of industries producing arts

and cultural commodities, was based on

of arts and cultural commodities; (2) the

construction of a basic framework for the

account; and (3) examples of arts and cultural

statistical frameworks formulated by other

countries and international organizations.

distinct arts and cultural commodities, shown

in Table 3 in this chapter.

12

In addition to

performing arts and museum commodities,

the ACPSA includes goods and services

that span sectors as varied as construction,

manufacturing, professional services, and

government.

Commodities

the detailed commodities to be included

in the ACPSA. Commodities, or goods and

services, are strongly linked to the industries

producing them. For example, motion

pictures, as a commodity, were selected

for inclusion. The motion picture industry,

consequently, became an ACPSA industry.

industries for the ACPSA was to consider

Artistic and cultural commodities are those

or cultural engagement, or are intended

primarily to facilitate access to such

commodities.

12 Commodities are goods and services such as

musical instruments (good) and dance performances

(service).

The ACPSA, therefore, includes not only

commodities whose primary activities are

arts and cultural, but also commodities

and industries that support the production

of arts and culture—i.e., the “creative

chain.” For example, the ACPSA includes

estimates for “symphony orchestras and

the production cycle of music performance,

the ACPSA also includes musical instrument

manufacturing, wholesale distribution of

music supplies, and musical instrument

stores.

As an additional example of the ACPSA’s

creative chain, consider that the account

includes newspaper, periodical, and book

publishing. However, printing is often

necessary for publishing. Consequently,

selected printing commodities and

industries are also included as arts and

cultural commodities and industries.

Determining the extent of the ACPSA’s

creative chain was in itself a highly selective,

and to some extent, an idiosyncratic

process. For example, the ACPSA includes

jewelry design and jewelry manufacturing

(an industry employing many jewelers

and precious stone and metal workers),

considered here as craft arts. However,

the ties between cultural production and

wholesale and retail sales of jewelry were

thought to be tenuous and outside the scope

of the account. Consequently, jewelry sales

were excluded from the ACPSA.

13

Similarly, the ACPSA includes fashion design,

but excludes clothing manufacturing and

apparel sales.

13 Wholesale and retail jewelery sales margins

commodities at the purchasers’ value.

10

ACPSA Framework

The process of selecting arts and cultural

commodities and industries was also

aided by considering the BEA’s provisional

framework for the ACPSA. Not all

and the reporting of ACPSA estimates

is not organized within its domains.

14

Nevertheless, the framework served as an

early tool for choosing ACPSA commodities

and industries.

The ACPSA framework is divided into three

domains: core; applied arts and design

services; and transversal. Each of these

domains, in turn, is further partitioned into

sub-domains.

Core Domains

A wide variety of ACPSA commodities

museums, libraries, and cultural centers;

live performance and music; visual arts;

written works; and audio-visual and

interactive media.

Museums,

libraries, and

cultural centers

Live performance

and music

Visual arts Wrien works

Audio-visual

and interacve

media

Adversing

services

Other design

services

Educaon

Governance,

funding, and

professional

support services

Infrastructure

14 ACPSA commodities unaligned with the

framework include electronic shopping for books

and music and rentals of theatrical costumes and

equipment.

“Museums, libraries, and cultural centers”

include museums, libraries and archives

(including government-operated libraries),

botanical gardens and zoos, and nature

parks. The “transversal” ACPSA domain

capturing governance also includes

operated museums.

Commodities falling under live performance

and music include performing arts

companies, such as music, dance, and

theater groups, as well as goods and

services supporting music such as sound

recording, the manufacture of musical

instruments, and music stores.

The visual arts sub-domain comprises

a number of detailed manufacturing

commodities representing craft arts.

Examples include the manufacture of

china and glass, jewelry and silverware,

and custom architectural woodwork. The

visual arts also contain several retail sales

shops, and camera and photographic supply

stores, as well as commodities supporting

the visual arts (i.e., the creative chain)

such as lead pencils and art goods and

photographic equipment.

11

Publishing (newspaper, periodical, and

book), along with its supporting printing

activities, make up the core sub-domain

labeled “written works”; motion picture

production and broadcasting feature

prominently in “audio-visual and interactive

media.”

15

Applied Arts and Design Services

The applied arts and design services domain

features advertising services. In order to

emphasize creative production, advertising

within the ACPSA excludes public relations,

media buying, distribution, and sign

painting.

16

This domain also includes architectural

services (including historical restoration

services) related to arts and cultural

structures, as well as all landscape

architectural services.

17

Additionally, this domain includes four

design services: interior design services;

industrial design services; graphic design

services; and “other design services” such

as jewelry and fur design. The ACPSA also

reports estimates for fashion design, a

detailed commodity within other design

services.

Transversal Domains

There are three transversal ACPSA domains:

education; governance, funding, and

professional services; and infrastructure.

Education includes “educational services,”

arts, and media arts (e.g., graphic design)

15 The ACPSA excludes sports from its

estimates of publishing and broadcasting production.

16 Media-buying agencies purchase advertising

time from media outlets and resell it to advertising

agencies.

17

architectural services to cultural institutional

projects, which represent approximately 2 percent

of all architectural services. An expanded measure

of architectural services will be considered for the

revised ACPSA planned for release in the fall of 2014.

departments of colleges and universities

(including state colleges and universities),

and music schools (except academic).

services feature art promoters and agents,

arts-related granting organizations and

unions, and government-operated museums

and parks. (Non-government museums are

included in the ACPSA’s core domain.)

The account’s transversal domain also

includes the construction sector—

educational facilities such as museums and

libraries, as well as selected amusement and

recreational structures related to the arts

(e.g., theaters, performing arts centers).

International Comparisons

Other arts and cultural satellite accounts

have been produced by countries including

Colombia, Spain, Finland, and, through its

United Kingdom.

Statistical frameworks (i.e., plans or

outlines) for measuring arts and culture

production have also been undertaken by

a number of international organizations,

including the World Intellectual Property

Organization (WIPO); the Organization for

Economic Cooperation and Development

(OECD); and the United Nations Conference

on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

By country, or by organization, some

accounts or frameworks emphasize arts

and culture, while others accentuate

creative industries. (The WIPO model,

alternatively, is a copyright-based model.)

That distinction, however, is based on

perspective. For example, the performing

arts, motion picture and sound recording,

and publishing are included in most

statistical models, whether framed as

arts and cultural production or creative

production.

12

Differences between models tend rather to

be at the margins. In its seminal document,

Creative Economy Report 2010, the UNCTAD

writes: “There is no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’

model of the creative industries, simply

different ways of interpreting the structural

characteristics of creative production.”

The design of the ACPSA was guided, in

part, by examples set by international

models, particularly the arts and cultural

frameworks designed by Statistics Canada,

the Australian Bureau of Statistics, and the

Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

18

There is

broad alignment of the types of production

selected for the ACPSA and those included

in the international models. For example,

the ACPSA and the three international

models considered include performing arts,

museums and libraries, motion pictures

and sound recording, publishing, and

architectural and design services.

However, differences tend to appear in

the production cycles captured by the

various models. For example, like the three

international models considered here, the

ACPSA includes music performance. As

part of music’s creative chain, the ACPSA,

along with the Australian and UNESCO

models, includes the manufacture of musical

instruments. The Canadian model does

not. The Canadian framework restricts the

production of musical instruments to the

expenses incurred when performing music

groups acquire musical instruments. In

other words, under the Canadian model,

the manufacture of musical instruments

18 As of November 2013, Australian and

Canadian satellite accounts were still under

development. The Australian and Canadian

frameworks discussed in this report may differ from

the ultimate satellite accounts of each country.

performing music groups.

19

Differences also appear in fashion and

jewelry production. The ACPSA and the

Canadian and UNESCO models include

fashion design but exclude the manufacture

of clothing and the wholesale and retail

sales of clothes.

20

The Australian model,

however, includes each of these in their

production cycle of clothing.

The Australian model also includes the

full production cycle of jewelry—design,

manufacture, and sales. The ACPSA, on the

other hand, includes jewelry design and

the manufacture of jewelry, but excludes

jewelry sales as a commodity. UNESCO

does likewise, but the Canadian model is

restricted to jewelry design.

21

The inclusion of computer systems design

also varies among the models considered.

The ACPSA includes computer systems

design, but it is restricted to custom

web design and computer applications

necessary to support motion picture and

sound recording production. The Canadian

framework also includes computer systems

design, but it is limited to custom web

design.

Alternatively, the Australian and UNESCO

frameworks include all computer systems

design production.

19 In the ACPSA, expenses incurred by

the total production of performing music groups

(e.g., symphony orchestras and chamber groups) .

But musical instruments are intermediate inputs to

performing music groups.

20 Fashion and jewelry design are part of

“other specialized design” within the ACPSA and the

three international models considered.

21 Ibid.

13

U.S. ACPSA Canada UNESCO Australia

Live performance of music Yes Yes Yes Yes

Manufacture of musical instruments Yes No Yes Yes

Fashion design Yes Yes Yes Yes

Clothing manufacturing No No No Yes

Wholesale/retail sales of clothing No No No Yes

Jewelry design Yes Yes Yes Yes

Jewelry manufacturing Yes No Yes Yes

Jewelry wholesale and retail sales No No No Yes

Computer systems design

Yes,

parally

in scope

1

Yes,

parally

in scope

2

Yes, fully

in scope

Yes, fully

in scope

1

Custom web design and applicaons supporng moon pictures and sound recording.

2

Custom web design.

14

A number of models have been developed to provide a systemac understanding of

the structural characteriscs of arts and culture industries. Chief among these are the

“concentric circles model” and the “WIPO copyright model.” The concentric circles model,

authored by Australian economist David Throsby, argues that the more pronounced the

cultural content of a parcular good or service, the stronger is the claim for inclusion of the

industry reporng it. Within the ACPSA, for example, moon pictures were selected as an

arts and cultural commodity. The moon picture industry, consequently, became an ACPSA

industry.

The WIPO (World Intellectual Property Organizaon) model, alternavely, captures

industries that produce or distribute copyrighted goods. ACPSA industries matching the

WIPO model include adversing, moon pictures, sound recording, publishing, design,

and television and radio broadcasng. The ACPSA does not, however, include WIPO-model

industries such as the manufacture and sales of toys and consumer electronics.

Recently, a new method of classifying “creave” industries was developed by Nesta, the

U.K.’s nonprot innovaon foundaon. The Nesta method emphasizes “creave intensity,”

which refers to the share of total employment within an industry that is engaged in creave

occupaons. Within the Nesta model, occupaons are scored on a grid of ve criteria:

(1) process novelty; (2) resistant to mechanizaon; (3) non-repeang output; (4) creave

funcon in process; and (5) interpretaon not transformaon. An occupaon’s creave

intensity is the composite of these scores.

Compared with the ACPSA and other internaonal models, parcularly the creave

industries dened by the U.K’s Department of Culture, Media & Sport, which Nesta targeted

for its analysis, the Nesta model results in a dierent set of industries. One dierence is

prinng. Because the occupaon of printers did not score highly on Nesta’s grid, prinng

industries are excluded from its list of creave industries. The ACPSA, alternavely, includes

prinng associated with newspapers, periodicals, books, and art reproducons.

A more pointed dierence is the ACPSA’s inclusion, and Nesta’s exclusion, of orist shops.

The decision to include “retail sales, orists” in the ACPSA stemmed from the industry’s

principal occupaon—oral designers. Data issued by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Stascs

show that in 2012 nearly half of the workers employed by orist shops were oral designers,

an occupaon classied among “art and design workers” within the Standard Occupaon

Classicaon (SOC) system.

However, “oral arrangers” earned a low score of two on Nesta’s creave grid. Florist shops,

consequently, are excluded from Nesta’s denion of creave industries.

15

ACPSA Commodities

Table 3. Commodities Included in the ACPSA

Theater

Dance

Opera

Symphonies

Circuses

Other

Independent arsts, writers, and

performers

Museums (art)

Museums (botanical and zoological)

Museums (children’s)

Museums (historical sites)

Museums (history)

Museums (natural history)

Museums (nature parks)

Museums (science)

Museums (other)

Fine arts

Other

Moon picture and video

Sound recording

Broadcasng

Telecommunicaons

16

Internet publishing and broadcasng

Other informaon services

Publishing:

Newspapers and periodicals

Cards, calendars, and related publishing

Books:

Educaon (K-12)

Higher educaon

Professional

Scholarly

All other professional, technical, and

scholarly books, in print

Adult con

Adult noncon

Juvenile con

Juvenile noncon

Religion

All other adult trade books

Children’s books

All other books

Soware publishing

Interior design services

Industrial design services

Graphic design services

Fashion design services

All other design services

Architectural services, historic restoraon

All other architectural services

Landscape architectural services

Computer systems design

Adversing

Photography services

17

Photonishing

Grant-making and giving services

Unions

Manufacturing (prinng)

Manufacturing (jewelry and silverware)

Manufacturing (other)

Wholesale trade

Retail trade

Construcon

Government

libraries

Rental and leasing

18

the federal government to measure and

document U.S. arts and cultural production

and its effect on the national economy. In

FY 2014, the ACPSA is subject to further

various stakeholders, including members

of the arts community, cultural researchers,

and international colleagues who

themselves are producing satellite accounts

on arts and culture.

The revised ACPSA estimates are planned

for release in the fall of 2014.

NAICS (North American Industrial

the NAICS. All revisions to the 2014 ACPSA

will be carried out for the full time series of

1998-2012. Additionally, the 2014 estimates

will include investment from “artistic

originals” (see text box below).

22

Moreover, the revised ACPSA will be

featured in a fall 2014 article in the BEA’s

Survey of Current Business.

22 The inclusion of artistic originals as

investment spending was part of the BEA’s recently

released comprehensive revisions to the national

income and product accounts. These revisions were

not available for the 2013 iteration of the ACPSA.

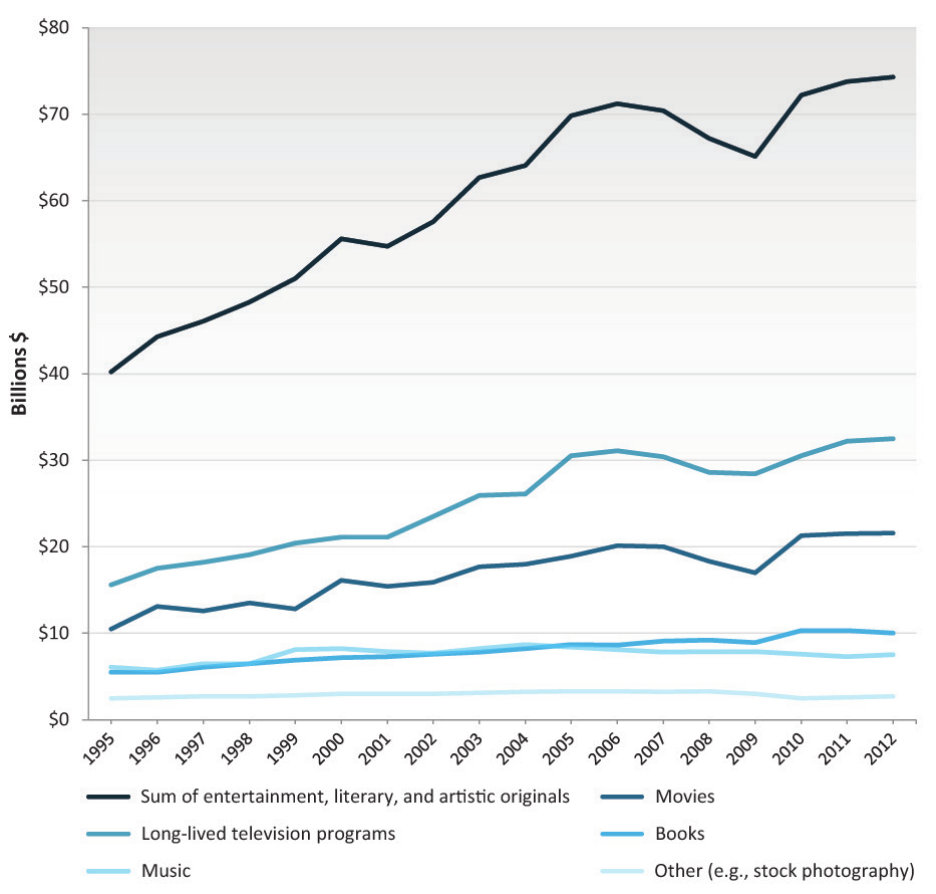

Typically conducted at ve-year intervals, comprehensive revisions of the industry economic

accounts allow the BEA’s esmates to beer reect the evolving nature of the U.S. economy.

These revisions also facilitate internaonal comparisons with economic data available from

other countries. The most recent of these revisions, scheduled for release in December

2013, will include the “capitalizaon” of entertainment, literary, and other arsc originals.

Under this new treatment, long-lived artwork produced by arsts, studios, and publishers

will be capitalized; that is, producon of long-lived artwork will be treated as an investment,

adding to the U.S. capital stock.

The BEA denes long-lived art works, or arsc originals, as theatrical movies, recorded

music, books, television programs, and “miscellaneous artworks” such as play scripts,

greeng card designs, and stock photography. Prior to the December 2013 revisions, arsc

producon costs were treated as current expenses, much like adversing or shipping costs,

and therefore had a limited role in the calculaon of GDP.

However, arsc originals can connue to earn revenue for decades aer producon.

(They are, therefore, “long-lived.”) As noted by the BEA, capitalizing arsc originals is an

important step toward fully recognizing the contribuon of intellectual property products to

economic growth. Recent esmates show that the capitalizaon of entertainment, literary,

and arsc originals added $73.8 billion to the U.S. economy in 2011.

19

Capitalization of Entertainment, Literary, and Artistic Originals

Additions to Gross Private Domestic Investment, and to GDP

Source: U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis

20

What timeframe does the ACPSA reference?

The ACPSA features a full time series of

estimates. For the current iteration of the

ACPSA, estimates are provided for the years

spanning 1998 to 2011. The revised ACPSA,

planned for release in the fall of 2014, will

contain estimates for 1998 through 2012.

Does the ACPSA include work done by self-

employed artists?

Yes. Self-employed workers, or “sole

proprietors,” are required to attach a

Form 1040 individual tax return if their

work meets certain requirements. First, the

primary purpose for engaging in the activity

must be for the purpose of generating

work must be done regularly.

If these criteria are met, Schedule C

attachments are required of self-employed

workers with business income of $400 over

and above expenses.

to indicate the industry of their principal

business (self-employed workers engaged

in more than one business must attach

multiple Schedules). The industries listed on

the Schedule C are in four-digit NAICS codes.

Examples include: “independent artists,

writers, and performers” (NAICS 7115);

“promoters of performing arts, sports,

and similar events” (NAICS 7113); and

“agents and managers for artists, athletes,

(NAICS 7114).

The U.S. Census Bureau calculates “non-

which non-employer statistics are available),

the bureau reported 987,714 individual

proprietorships in “performing arts,

spectator sports, and related industries”

(NAICS 711). Of those, 704,356 (more than

70 percent) were “independent artists,

writers, and performers.”

The BEA draws on the Census Bureau’s

non-employer statistics to calculate NIPAs

and industry accounts, including the ACPSA.

Notably, the BEA adjusts the non-employer

estimates of Schedule C noncompliance.

Does the ACPSA capture independent

musicians who work on contract?

As discussed above, the ACPSA includes

production by self-employed workers,

including musicians and other artists.

Within the NAICS system, freelance

musicians are included in NAICS 71113,

“musical groups and artists.”

Are there special considerations for tax-

exempt arts organizations?

For many of the arts and cultural industries

included in the ACPSA, output and value

added are based on the industries’ revenues

(i.e., sales). However, basing production on

the revenue of tax-exempt organizations

would likely understate that value. Tax-

exempt performing arts groups and

museums, for example, often provide special

discounted or free services, resulting,

naturally, in lower revenue.

To correct for this potential under-

estimation, expenditures in addition

to revenues are used to measure the

production of tax-exempt arts and cultural

organizations.

Are there special considerations for museums

and museum workers?

Within NAICS, the museum industry (NAICS

71211) excludes college and government-

colleges and government are represented

21

by their respective sectors—educational

services (NAICS 61) and government, which

23

What is value added?

The value added of an industry, also

referred to as the industry’s gross domestic

product, is the contribution of a private

industry or government sector to overall

between and industry’s output and the cost

of intermediate inputs such as energy costs

goods, and services.

To illustrate, the output of dance companies

includes the cost of pointe shoes (the shoes

worn by ballet dancers when dancing

en pointe). The value added of dance

companies excludes the cost of pointe shoes,

which were produced by other industries

such as shoe manufacturers.

The ACPSA draws on “inter-industry” or I-O

analysis, which, in turn, comprises “make”

and “use” tables. The make table shows the

production of commodities (i.e., goods and

services), while the use table shows the uses

Final demand consists of the transactions

change in private inventories; exports

and imports; and government. Put simply,

arts and cultural production purchased by

U.S. households (personal consumption);

change in private inventories); foreign

purchases (exports); and government.

23 Estimates for the government sector draw

the Economic Census, is conducted by the U.S. Census

Imports are U.S. purchases of foreign-

produced arts and cultural commodities,

Are the ACPSA estimates adjusted for

The current ACPSA estimates, and those

planned for release in the fall of 2014, are

the BEA’s process for generating “real”

estimates is complex, the agency warns

will likely result in more distortion than is

present in current-dollar ACPSA estimates.

Can I use the ACPSA to generate measures of

arts and cultural production for my state or

metro area?

Current ACPSA estimates (and the revised

ACPSA estimates planned for the fall

of 2014) are national calculations and

production. Because the BEA has access to

data and methodologies unavailable to the

public, national ACPSA estimates cannot

regional production.

22

A comprehensive measure of arts and

cultural production would include not only

commodities and industries, but also the

work done by arts and cultural workers,

regardless of the industries employing

them. The ACPSA, for example, measures

employment in performing arts industries.

In 2012, the performing arts employed

22,500 musicians and singers. However,

the ACPSA excludes religious organizations

(e.g., churches, synagogues, missions), an

industry that employed more than 8,000

musicians in that year.

This section outlines the occupational

dimension to arts and cultural production

using data from the Occupational

Employment Survey (OES), produced by the

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). Unlike

the ACPSA, which captures arts and cultural

production by sole proprietors (i.e., non-

employers), the OES excludes self-employed

workers. It does, nonetheless, provide

employment and earnings data for detailed

occupations by industry. Consequently, the

OES is well-suited to examining arts and

cultural workers and the industries in which

they are employed.

This section presents three tiers of arts

and cultural occupations: (1) core arts and

cultural occupations; (2) technical and

supporting occupations; and (3) managers

working in arts and cultural industries.

Including all three tiers of arts and cultural

occupations reveals the share of the labor

force directly responsible for the production

of arts and cultural goods.

Page 37 lists the data tables that accompany

Part II of this document.

Occupaon Employment Stascs (OES) is a collaborave program between the BLS and

state workforce agencies. The OES surveys 200,000 non-farm establishments every six

months, taking three years to fully collect the sample of 1.2 million establishments. OES

data are used to report employment and wage esmates for about 800 occupaons at

naonal, state, metropolitan, and non-metropolitan levels.

The OES also reports employment and wage esmates by industry. At the naonal level,

esmates are reported for 450 industries, which are categorized by the North American

Industry Classicaon System (NAICS).

23

In accordance with the approach used

of U.S. arts and cultural occupations

was guided by asking if the considered

occupation would cease to exist if the

tasks and responsibilities of creative work

were removed. Answering this question

yielded the three tiers of arts and cultural

occupations discussed below.

Workers in core arts and cultural

occupations are responsible for the creative

element of arts and cultural products,

whether produced by an arts and cultural

industry or not. This tier includes 39

distinct occupations—in 2012, employment

in core arts and cultural occupations totaled

1.5 million wage and salary workers, while

annual median earnings ranged from

$80,880 for art directors to roughly $24,000

Occupations included in Tier 1 span jobs as

varied as architects and designers, reporters

and photographers, and multimedia artists

and jewelry makers. Nearly three out of

four occupations on this list are grouped

under the major occupation group labeled

“arts, design, entertainment, sports, and

media occupations,” or major standard

occupation code 270000.

24

This major

occupation group is divided into several

broad occupation groups comprising core

arts and cultural occupations. Drawing on

OES data for wage and salary workers in

2012, core occupations in the major groups

are summarized below.

As noted above, the OES excludes self-

employed workers from its datasets.

Therefore, recognizing that self-employed

workers make up a large portion of the U.S.

arts workforce, this section uses another

data source (the Current Population Survey)

24 Please see Appendix B for a discussion on

standard occupation codes.

to estimate the percentage of self-employed

workers within each occupational category

described below.

Artists and Related Workers (i.e., Visual

Artists)

multimedia artists and animators; artists and

related workers, all others (e.g., calligraphers,

tattoo artists)

Main industries: advertising and public

relations; publishing; independent artists,

writers, and performers; motion pictures

Art directors make up the greatest number

of workers in this occupation group

(31,570), while “other artists,” such as

calligraphers and tattoo artists, are the

smallest (6,850). Art directors are also the

best paid, earning an average annual salary

of $80,880 in 2012; earnings are lowest for

craft artists, whose annual salaries averaged

$29,600.

Among core arts and cultural workers,

artists and related workers hold some of the

highest rates of self-employment. In 2010,

nearly 60 percent of the artists in this group

were self-employed.

The industries employing the greatest

numbers of salaried artists and related

workers include: advertising and public

relations; independent artists, writers, and

performers; and motion pictures.

25

In 2012,

for example, advertising and public relations

than one-third of all salaried art directors.

Of the 29,270 salaried multimedia artists

and animators, 9,130 (30 percent) worked

in the motion picture industry.

25 The U.S. Census Bureau denes “independent

artists, writers, and performers” (NAICS 71151) as

freelance individuals primarily engaged in performing

in artistic productions, in creating artistic and cultural

works, or in providing technical expertise necessary for

these productions. The independent artists, writers, and

performers shown here refer to business establishments

with workers on payrolls.

24

Designers

designers; interior designers; merchandise

displayers and window trimmers; set and

exhibit designers; designers, all other (e.g.,

jewelry and fur designers)

Main industries: specialized design services;

publishing; manufacturing; retail sales

In this group, graphic designers number the

largest. In 2012, 191,440 salaried graphic

designers were employed. Alternatively,

set and exhibit designers and designers

designers) make up the smallest number

of workers in this group—roughly 8,000

employed in both occupations.

Among design professionals, fashion

designers and industrial designers earn

the highest annual salaries—$62,860 and

$59,610, respectively, on average, in 2012.

Like visual artists, high percentages of

designers are self-employed—about 30

percent of each design occupation. However,

among salaried workers in this group,

industries employing the greatest numbers

vary by type of designer. Specialized design

companies (companies that specialize in

graphic, industrial, and fashion design),

manufacturing, and publishing industries

In 2012, for example, publishing industries

staffed roughly 25,000 graphic designers

(nearly the same number staffed by

shops, under retail sales, employed 31,220

the salaried workers in that occupation.

Performing Artists

Actors; producers and directors; dancers;

choreographers; music directors and

composers; musicians and singers; other

entertainers (e.g., comedians, jugglers,

acrobats)

Main industries: performing arts; motion

pictures; educational services; broadcasting

In 2012, salaried actors numbered 70,540,

and producers and directors numbered

87,010. Employment for salaried dancers

and choreographers was lower—11,390 and

7,400, respectively. Musicians and singers

totaled 42,100, while music directors and

composers were 24,940 in number. In 2012,

16,630 wage and salary workers were

employed as “other entertainers.”

Due to disclosure concerns, OES data omit

earnings for many of the performing arts

occupations in this group. Of those tracked,

however, producers and directors earn the

highest salaries—annual median earnings of

$71,350 in 2012.

Among performing artists, rates of self-

employment range from a high of about 43

percent of musicians and other entertainers,

to a low of 9-10 percent of dancers and

choreographers.

Not surprisingly, the performing arts

industry hires many performing artists.

However, motion pictures, schools,

broadcasting, and even religious

organizations factor in, too. In 2012, for

example, almost 80 percent of salaried

choreographers were employed by “other

private schools,” an industry that includes

The motion picture industry employs more

producers and directors than any other

a close second, however, is radio and

television, which staffed roughly 20,000

producers and directors. And of the 42,100

salaried musicians in 2012, half were

25

employed by performing arts companies,

but another 20 percent were on staff at

religious organizations such as churches and

synagogues.

In 2012, motion pictures and the performing

arts, combined, employed roughly three

number of actors, 15,400 in 2012, are

employed by “accounting, tax preparation,

bookkeeping, and payroll services.” This

forming separate companies to carry out

their payroll functions, including paying

engaged actors.

Announcers

Radio and television announcers; public

address system and other public announcers

Main industries: radio and television

broadcasting; drinking places (i.e., bars);

independent artists, writers, and performers

Although radio and television announcers

far outnumber public address and other

public announcers (31,340 vs. 8,120),

earnings among workers in these

occupations are comparable, with radio

and television announcers earning an

average salary of $28,020 in 2012, and

public address announcers earning $26,230.

Additionally, 35 percent of workers in both

occupations are self-employed.

Differences exist, however, in the industries

employing the two occupations. Most radio

and television broadcasters work in radio,

rather than television broadcasting (25,440

announcers in 2012), while most public

address system announcers (which includes

disc jockeys at weddings, parties, and other

public events) work in drinking places, i.e.,

bars (2,590), and in the industry labeled

independent artists, performers, and writers

(1,970).

Media Occupations

Broadcast news analysts; reporters and

correspondents; editors; writers and authors;

photographers

Main industries: newspaper publishers;

television broadcasting; photographic

services

Of the media occupations included in Tier 1,

editors number the largest—99,000 salaried

workers in 2012. Next in employment rank

are photographers (56,140); reporters

and correspondents (45,570); writers and

authors (41,990); and broadcast news

analysts (5,170).

Editors, writers and authors, and broadcast

news analysts all earn roughly $54,000

to $55,000, annually, on average, while

photographers earn an average of $28,490.

Photographers also have high self-

employment rates (almost 63 percent in

2012), compared with self-employment

rates of 14-16 percent of reporters and

correspondents and of editors.

Among all workers in arts and cultural

occupations, writers and authors have the

highest self-employment rate—68 percent

in 2012.

Among wage and salary media workers,

however, newspaper publishing is a

main employer. In 2012, newspaper

publishers staffed 25,980 reporters and

correspondents and 21,760 editors.

Although newspaper publishers hire writers

and authors (3,550 in 2012), salaried

workers in this occupation are also likely

to be employed by advertising and public

industries (3,300), and independent artists,

writers, and performers (3,060).

In 2012, newspaper publishers staffed 3,480

photographers. However, most salaried

photographers (37,560) work in photo-

graphic services, which includes portrait

and commercial photography studios.

26

Education and Library Occupations

Art, drama, and music teachers,

postsecondary; English language and

literature teachers, postsecondary;

communications teachers, postsecondary;

archivists; curators; audio-visual and

multimedia collection specialists; librarians

Main industries: colleges and universities;

elementary and secondary schools;

government; museums and historical sites

Among this group of core arts and cultural

occupations, librarians and postsecondary

art and drama teachers number the largest.

In 2012, librarian employment totaled

140,280 and college art teachers totaled

92,570.

26

Postsecondary art, drama, and

music teachers, however, are better paid,

earning an annual average of $62,160

in 2012 compared with average annual

earnings of $55,370 for librarians.

The postsecondary education occupations

included here also include English language

and literature teachers and communications

teachers, and architcture teachers,

numbering 72,680, 30,030, and 7,290

workers, respectively, in 2012. In that same

year, postsecondary teachers in English and

in communications earned between $60,000

and $62,000, on average; architecture

teachers earned an average annual salary of

$71,610.

In 2012, salaried curators numbered 10,370,

while archivists numbered roughly half that

number (5,640). Employment among audio-

visual and multimedia collection specialists

totaled 8,690 in 2012. Average annual

earnings for workers in these occupations

ranged from $49,590 for curators and

$47,340 for archivists, to $43,350 for audio-

visual and multimedia collection specialists.

Few workers in education and library

occupations are self-employed—virtually no

26 Includes design and craft teachers and art

history professors.

librarians and only 2.6 percent of curators

employ many of the people in these

professions. For example, local governments

(including public libraries and public

elementary and secondary schools) staffed

96,700 librarians, or almost 70 percent of

employs many curators (1,500 in 2012).

However, curators are more commonly

employed by museums and historical

sites—5,660 in 2012.

Architects

Architects; landscape architects

Main industries: architectural and

engineering services; government

Measuring salaried workers, the OES reports

82,720 architects and 15,750 landscape

architects in 2012. Annual median earnings

for the two occupations were $73,090 and

$64,180, respectively.

occupations are self-employed. But

among salaried architects and landscape

architects, most work in architectural and

engineering services (an industry that

2012, architectural and engineering services

employed 71,160 architects (86 percent

of the salaried profession) and 9,090

landscape architects (58 percent of salaried

landscape architects).

Agents and Business Managers of Artists,

Performers, and Athletes

Main industries: agents and managers for

artists, entertainers, athletes, and other

sports, and similar events

Half of all agents and business managers are

self-employed. However, the OES reported

11,770 salaried workers in this occupation

27

in 2012; their average annual salary was

$63,370.

Most salaried agents and managers of

artists, performers, and athletes work in the

industry producing their services, “agents

and managers for artists, athletes, and

performing arts, sports, and similar events.”

In 2012, these two industries employed

7,320 and 1,000 agents and managers,

respectively.

Jewelers and Precious Stone and Metal

Workers

Jewelers and precious stone and metal

workers, a specialized type of craft artist,

numbered 22,060 in 2012—their average

annual earnings were $35,350.

Most jewelers and precious stone/metal

workers are employed by jewelry, luggage,

and leather goods stores (10,700) or by

manufacturers of jewelry and silverware

(6,930).

27

27 Most OES statistics by occupation are reported

at the four-digit industry level. “Jewelry, luggage, and

leather goods stores,” NAICS 4483, includes the more

detailed industry, “jewelry stores,” NAICS 44831. Most

jewelers working in this retail trade industry are likely

employed by jewelry stores, rather than by luggage or

leather goods stores.

While the occupations listed in Tier 1

represent the primary source of arts

and cultural creativity, the technical and

supporting occupations in Tier 2 are

required to assemble and distribute arts

and cultural products. This tier comprises

23 occupations spanning jobs as varied

as library technicians, printers, and forest

conservationists. Employment in salaried

technical and supporting occupations

totaled 715,700 in 2012, and median annual

wages for workers in these occupations

ranged from a high of $64,450 (theatrical

and performance make-up artists) to a low

of $18,750 (models).

technical and supporting occupations. For

editors and camera operators are self-

employed. Alternatively, self-employment

rates are virtually zero among library

technicians, costume attendants, and print

binders.

The following summarizes the technical and

supporting occupations in Tier 2.

Museum and Library Technicians

Main industries: museums; government

Library technicians—100,230 employed in

2012—largley work in local government

(i.e., local government libraries) and in local

government schools. Museum technicians

and conservators—10,430 employed in

2012—generally work in the industry

labeled “museums, historical sites, and

similar institutions,” and for the federal

government.

Workers in both occupations earned median

annual salaries of roughly $30,000 to

$38,000; few library or museum technicians

are self-employed.

28

Media and Communication Equipment

Workers

Audio and video equipment technicians;

broadcast technicians; radio operators; sound

engineering technicians; camera operators,

editors

Main industries: motion pictures;

broadcasting

Among media and communication

equipment workers, audio and video

technicians are the most prevelant—54,310

salaried workers in this occupation in

2012. Broadcast technicians, who set up

and operate the electronic equipment

used to transmit radio and television

programs, numbered 31,640. Film and

video editors, though fewer in number, are

the best paid media and communication

equipment workers—in 2012, workers in

this occupation earned an annual average of

$51,300.

Motion picture and video industries (NAICS

5121) are a major employer of media and

communication equipment workers. In

2012, for example, this industry staffed

audio and video equipment technicians.

Broadcasting, too, employs media and

communication equipment workers—three

out of four salaried broadcast technicians

works in the radio and television

broadcasting industry (NAICS 5151).

Personal Care and Service Occupations

Motion picture projectionists; costume

attendants; makeup artists, theatrical and

performance

Main industries: motion pictures; performing

arts

In 2012, employment numbered 8,030

motion picture projectionists; 5,660

costume attendants; and 1,950 makeup

artists. Although small in number, makeup

artists earn the most among the personal

care and service occupations on Tier

2—$64,450, on average, in 2012; makeup

artists are also more likely to be self-

employed.

Motion picture and video industries employ

90 percent of motion picture projectionists

and more than 50 percent of theatrical

and performance makeup artists. Costume

attendants also work in motion pictures

and videos (about 20 percent of wage and

salary attendants), but they are more likely