PERSONALITY PROCESSES AND INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCES

The Do Re Mi’s of Everyday Life: The Structure and Personality

Correlates of Music Preferences

Peter J. Rentfrow and Samuel D. Gosling

University of Texas at Austin

The present research examined individual differences in music preferences. A series of 6 studies

investigated lay beliefs about music, the structure underlying music preferences, and the links between

music preferences and personality. The data indicated that people consider music an important aspect of

their lives and listening to music an activity they engaged in frequently. Using multiple samples,

methods, and geographic regions, analyses of the music preferences of over 3,500 individuals converged

to reveal 4 music-preference dimensions: Reflective and Complex, Intense and Rebellious, Upbeat and

Conventional, and Energetic and Rhythmic. Preferences for these music dimensions were related to a

wide array of personality dimensions (e.g., Openness), self-views (e.g., political orientation), and

cognitive abilities (e.g., verbal IQ).

At this very moment, in homes, offices, cars, restaurants, and

clubs around the world, people are listening to music. Despite its

prevalence in everyday life, however, the sound of music has

remained mute within social and personality psychology. Indeed,

of the nearly 11,000 articles published between 1965 and 2002 in

the leading social and personality journals, music was listed as an

index term (or subject heading) in only seven articles. The eminent

personality psychologist Raymond Cattell even remarked on the

bewildering absence of research on music, “So powerful is the

effect of music . . . that one is surprised to find in the history of

psychology and psychotherapy so little experimental, or even

speculative, reference to the use of music” (Cattell & Saunders,

1954, p. 3).

Although a growing body of research has identified links be-

tween music and social behavior (Hargreaves & North, 1997;

North, Hargreaves, & McKendrick, 1997, 2000), the bulk of stud-

ies have been performed by a relatively small cadre of music

educators and music psychologists. We believe that an activity that

consumes so much time and resources and that is a key component

of so many social situations warrants the attention of mainstream

social and personality psychologists. In the present article we

begin to redress the historical neglect of music by exploring the

landscape of music preferences. The fundamental question guiding

our research program is, Why do people listen to music? Although

the answer to this question is undoubtedly complex and beyond the

scope of a single article, we attempt to shed some light on the issue

by examining music preferences. In this research we take the first

crucial steps to developing a theory of music preferences—a

theory that will ultimately explain when, where, how, and why

people listen to music.

Why Study Music Preferences?

Recently, a number of criticisms have been raised about the lack

of attention to real-world behavior within social and personality

psychology (e.g., Funder, 2001; Hogan, 1998; Mehl & Penne-

baker, 2003; Rozin, 2001). For example, Funder (2001) noted that

although there is a wealth of information regarding the structure of

personality, “the catalog of basic facts concerning the relationships

between personality and behavior remains thin” (p. 212). Accord-

ing to Funder, one way researchers can address this issue is to

extend their research on the structural components of personality

to include behavior that occurs in everyday life. Still others have

criticized the field for focusing on a narrow subset of social

phenomena and ignoring many basic, pervasive social activities.

Rozin (2001) opined, “Psychologists should learn . . . to keep their

eyes on the big social phenomena, and to situate what they study

in the flow of social life” (p. 12). In short, there is a growing

concern that the breadth of topics studied by many research psy-

chologists is too narrow and excludes many important facets of

everyday life that are worthy of scientific attention. Music is one

such facet.

Music is a ubiquitous social phenomenon. It is at the center of

many social activities, such as concerts, where people congregate

Peter J. Rentfrow and Samuel D. Gosling, Department of Psychology,

University of Texas at Austin.

Preparation of this article was supported by National Institute of Mental

Health Grant MH64527-01A1. We are grateful to Matthias Mehl, Sanjay

Srivastava, and Simine Vazire for their helpful comments on this research;

Patrick Randall and Sanjay Srivastava for their statistical advice; Sarah

Glenney for her assistance with Study 1; and Paradise Kaikhany, Mathew

Knapek, Jennifer Malaspina, Yvette Martinez, Scott Meyerott, Ying Jun

Puk, Stacie Scruggs, and Jennifer Weathers for their assistance with the

data collection in Studies 4 and 5.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Peter J.

Rentfrow, Department of Psychology, University of Texas at Austin,

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2003, Vol. 84, No. 6, 1236–1256

Copyright 2003 by the American Psychological Association, Inc. 0022-3514/03/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.6.1236

1236

to listen to music and talk about it. Even in social gatherings where

music is not the primary focus, it is an essential component—

imagine, for instance, a party or wedding without music.

Music can also satisfy a number of needs beyond the social

context. Just as individuals shape their social and physical envi-

ronments to reinforce their dispositions and self-views (Buss,

1987; Gosling, Ko, Mannarelli, & Morris, 2002; Snyder & Ickes,

1985; Swann, 1987; Swann, Rentfrow, & Guinn, 2002), the music

they select can serve a similar function. For instance, an individual

high in Openness to New Experiences may prefer styles of music

that reinforce his or her view of being artistic and sophisticated.

Furthermore, individuals may seek out particular styles of music to

regulate their emotional states; for example, depressed individuals

may choose styles of music that sustain their melancholic mood.

Although the myriad psychological and social processes influenc-

ing people’s music preferences are undoubtedly complex, it is

reasonable to suppose that examining the ties between basic per-

sonality traits and music preferences could shed some light on why

people listen to music.

The present research is designed to extend theory and research

into people’s everyday lives by examining individual differences

in music preferences. By exploring the structure of music prefer-

ences and its links to personality, self-views, and cognitive ability,

we begin to lay the foundations on which a broad theory of music

preferences can be built.

What Do We Already Know About Music Preferences?

Although music has enjoyed considerable attention in cognitive

psychology (e.g., Bharucha & Mencl, 1996; Chaffin & Imreh,

2002; Deutsch, 1999; Drayna, Manichaikul, de Lange, Sneider, &

Spector, 2001; Krumhansl, 1990, 2000, 2002; Radocy & Boyle,

1979; Sloboda, 1985), biological psychology (e.g., Oyama et al.,

1983; Rider, Floyd, & Kirkpatrick, 1985; Standley, 1992; Todd

1999), clinical psychology (Chey & Holzman, 1997; Diamond,

2002; Dorow, 1975; Hilliard, 2001; Wigram, Saperston, & West,

1995), and neuroscience (e.g., Besson, Faita, Peretz, Bonnel, &

Requin, 1998; Blood & Zatorre, 2001; Blood, Zatorre, Bermudez,

& Evans, 1999; Clynes, 1982; Marin & Perry, 1999; Peretz,

Gagnon, & Bouchard, 1998; Peretz & Hebert, 2000; Rauschecker,

2001), very little is known about why people like the music they

do.

Clearly, individuals display stronger preferences for some types

of music than for others. But what determines a person’s music

preferences? Are there certain individual differences linking peo-

ple to certain styles of music? The few studies that have examined

music preferences suggest some links to personality (Arnett, 1992;

Cattell & Anderson, 1953b; Cattell & Saunders, 1954; Little &

Zuckerman, 1986; McCown, Keiser, Mulhearn, & Williamson,

1997), physiological arousal (Gowensmith & Bloom, 1997; Mc-

Namara & Ballard, 1999; Oyama et al., 1983; Rider et al., 1985),

and social identity (Crozier, 1998; North & Hargreaves, 1999;

North, Hargreaves, & O’Neill, 2000; Tarrant, North, & Har-

greaves, 2000).

Personality

Cattell was among the first to theorize about how music could

contribute to understanding personality. He believed that prefer-

ences for certain types of music reveal important information

about unconscious aspects of personality that is overlooked by

most personality inventories (Cattell & Anderson, 1953a, 1953b;

Cattell & Saunders, 1954; Kemp, 1996). Accordingly, Cattell and

Anderson (1953a) created the I.P.A.T. Music Preference Test, a

personality inventory comprising 120 classical and jazz music

excerpts in which respondents indicate how much they like each

musical item. Using factor analysis, Cattell and Saunders (1954)

identified 12 music-preference factors and interpreted each one as

an unconscious reflection of specific personality characteristics

(e.g., surgency, warmth, conservatism). Whereas Cattell believed

that music preferences provide a window into the unconscious,

most researchers have regarded music preferences as a manifesta-

tion of more explicit personality traits. For example, sensation

seeking appears to be positively related to preferences for rock,

heavy metal, and punk music and negatively related to preferences

for sound tracks and religious music (Little & Zuckerman, 1986).

In addition, Extraversion and Psychoticism have been shown to

predict preferences for music with exaggerated bass, such as rap

and dance music (McCown et al., 1997).

Physiological Arousal

Another line of research revealing links between music prefer-

ences and personality has focused on the physiological correlates

of music preferences. For example, heavy metal fans tend to

experience higher resting arousal than country music fans. Fur-

thermore, listening to heavy metal music has been shown to

increase the arousal level of heavy metal fans beyond that of

country music fans (Gowensmith & Bloom, 1997). Similarly,

preference for highly arousing music (e.g., heavy metal, rock,

alternative, rap, and dance) appears to be positively related to

resting arousal, sensation seeking, and antisocial personality (Mc-

Namara & Ballard, 1999).

Social Identity

Additional evidence linking music preferences and personality

comes from research on social identity. For example, North and

Hargreaves (1999) found that people use music as a “badge” to

communicate their values, attitudes, and self-views. More specif-

ically, they examined the characteristics of the prototypical rap and

pop music fan. Participants’ music preferences were related, in

part, to the degree to which their self-views correlated with the

characteristics of the prototypical music fan. This relationship,

however, was moderated by participants’ self-esteem, such that

individuals with higher self-esteem perceived more similarity be-

tween themselves and the prototype than did individuals with low

self-esteem. Similar findings in different populations, age groups,

and cultures provide additional support for the notion that people’s

self-views and self-esteem influence music preferences (North,

Hargreaves, & O’Neill, 2000; Tarrant et al., 2000).

Although the results from these studies provide intriguing

glimpses into relationships between music preferences and person-

ality, taken together they offer an incomplete picture. For instance,

most of the studies examined only a limited selection of music

genres: Cattell and Saunders (1954) examined preferences for

classical and jazz music, Gowensmith and Bloom (1997) examined

preferences for heavy metal and country music, and North and

1237

MUSIC PREFERENCES

Hargreaves (1999) examined preferences for pop and rap music.

Moreover, most of the studies examined only a few personality

dimensions: Little and Zuckerman (1986) examined sensation

seeking, McCown et al. (1997) examined Extraversion and Psy-

choticism, and McNamara and Ballard (1999) examined antisocial

personality. A theory of music preferences needs to be based on a

more comprehensive exploration of the music and personality

domains. Thus, we build on the provocative findings provided by

this important early work with a series of studies using a broad and

systematic selection of music genres and personality dimensions.

Overview of Studies

Given the paucity of research on music preferences, we sought

to explore the structure of music preferences and to examine its

relationship to personality. The questions guiding this research

were as follows: How much importance do people give to music?

What are the basic dimensions of music preferences? How can

they be characterized? How do they relate to existing dimensions

of personality?

In Study 1 we examined lay beliefs about the relevance and

importance of music in people’s everyday lives. Adopting a factor-

analytic approach, in Studies 2–4 we examined the basic structure

of music preferences. In Study 5 we examined the psychological

attributes of different styles of music. In Study 6, we examined the

relationship between music preferences and personality, self-

views, and cognitive ability.

Study 1: Lay Beliefs About the Importance of Music

It seemed self-evident to us that music is an important part of

individuals’ lives, but before embarking on this program of re-

search, we wanted to determine whether our beliefs were empiri-

cally grounded. Thus, the purpose of this study was simply to

develop a general understanding of lay beliefs about the role of

music in everyday life. How important is music to people? Is

music more or less important than other leisure activities? Do

individuals believe that their music preferences reveal information

about their personality? What are the contexts in which individuals

typically listen to music? To examine these issues, we adminis-

tered a questionnaire that would provide some preliminary

answers.

Method

Participants. The sample was made up of 74 University of Texas at

Austin undergraduates who volunteered in exchange for partial fulfillment

of an introductory psychology course requirement during the spring se-

mester of 2001. The sample included 30 (40.5%) women and 44 (59.5%)

men, 2 (2.7%) African Americans, 7 (9.5%) Asians, 5 (6.8%) Hispanics, 49

(66.2%) Whites, and 11 (14.8%) individuals of other ethnicities. The

average age of participants was 18.9 years (SD ⫽ 2.3).

Procedure. On arrival, participants were introduced to a study of

lifestyle and leisure preferences. They were then asked to complete a

packet of questionnaires that were designed to assess their attitudes and

beliefs about various lifestyle and leisure activities. Our first question dealt

with the importance individuals give to various lifestyle and leisure activ-

ities. Participants were presented with a list of eight different activities and

were asked to indicate how personally important each domain was to

them using a scale ranging from 0 (Strongly disagree) to 100 (Strongly

agree; e.g., “Music is very important to me”). The next question was about

participants’ beliefs about how much their lifestyle and leisure activities

say about their self-views, using a scale ranging from 0 (Strongly disagree)

to 100 (Strongly agree; e.g., “My movie preferences say a lot about who I

am”); their personalities, using a scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree)

to7(Strongly agree; e.g., “My television preferences reveal a great deal

about my personality”); and other people’s personalities, using a scale

ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree)to7(Strongly agree; e.g., “People’s

television preferences reveal a great deal about their personality”). Finally,

using a scale ranging from 1 (Never)to7(All the time), participants were

asked to indicate the frequency with which they engaged in various

activities while in nine different contexts (alone at home, going to sleep,

hanging out with friends, driving, getting up in the morning, studying,

working, exercising, and getting ready to “go out”; e.g., “How often do you

read books or magazines while at home?”).

1

Results and Discussion

How much importance do individuals place on music? As

shown in Figure 1, along with hobbies (M ⫽ 82.0, SD ⫽ 19.3),

music (M ⫽ 78.1, SD ⫽ 23.6) was considered the most important

of the domains we examined; the difference between music and

hobbies was not significant, t(69) ⫽ 1.12, ns. Furthermore, music

was considered significantly more important than the next item,

food preferences, t(69) ⫽ 3.56, p ⬍ .001. Overall, participants’

music preferences were at least as important as or more important

than the other seven domains, supporting our belief that music is

an important part of people’s lives.

How much do people believe music preferences say about

themselves? As shown in Figure 2, along with hobbies (M ⫽

76.5, SD ⫽ 23.4) and bedrooms (M ⫽ 63.4, SD ⫽ 31.8), music

preferences (M ⫽ 69.4, SD ⫽ 25.7) were believed to reveal a

considerable amount of information about participants’ personal

qualities; the differences between music and hobbies and music

and bedrooms were not significant (ts ⬍ 1.91, ps ⬎ .06). Overall,

participants believed that their music preferences revealed as much

if not more information about themselves than the other domains.

How much do people believe music preferences reveal about

their own and others’ personalities? As shown in Figure 3,

participants considered hobbies to reveal as much about their own

personalities as music (Ms ⫽ 5.51, 5.26; SDs ⫽ 1.54, 1.78),

t(71) ⫽ .91, ns, yet music was believed to reveal significantly more

than the next highest activity, movie preferences (M ⫽ 4.54,

SD ⫽ 1.78), t(71) ⫽ 2.66, p ⬍ .01.

Furthermore, music preferences (M ⫽ 5.89, SD ⫽ 1.61) were

second only to hobbies (M ⫽ 5.89, SD ⫽ 1.15) in terms of what

participants believed they revealed about others’ personalities,

t(71) ⫽ 2.58, p ⬍ .025. In addition, music was believed to provide

significantly more information about others than book and maga-

zine preferences (M ⫽ 4.74, SD ⫽ 1.75), t(71) ⫽ 2.54, p ⬍ .025.

Thus, participants believed that music preferences reveal at least as

1

Participants were not asked how often they engaged in all of the

activities in all the situations because it did not always make sense to do so.

For example, it did not seem appropriate to ask participants how often they

read books while driving because reading is probably an uncommon

activity in this situation.

1238

RENTFROW AND GOSLING

much about their personalities and the personalities of others as the

other lifestyle and leisure domains (with the exception of hobbies).

In which contexts do individuals listen to music? The results

shown in Figure 4 indicate that participants reported listening to

music frequently in every situation listed (M ⫽ 5.19, SD ⫽ .93). In

general, music is listened to most often while driving, alone at

home, exercising, and hanging out with friends. In addition, the

results indicated that participants listened to music more often than

any of the other activities (i.e., watching television, reading books,

and watching movies) across all the situations (ts ⬎ 3.3, ps ⬍ .001)

except while going to sleep, in which case watching television was

as common as listening to music, t(72) ⫽ 1.5, ns. These findings

provide further support for the pervasiveness of music in people’s

everyday lives.

Summary

We sought information concerning lay beliefs about music. The

results strongly support the notion that music is important to

people and that individuals believe that the music people listen to

provides information about who they are. Moreover, the fact that

our participants reported listening to music more often than any

other activity across a wide variety of contexts confirms that music

plays an integral role in people’s everyday lives. In general, these

Figure 2. Lay beliefs about the amount of information various preferences and activities reveal about personal

qualities.

Figure 1. Lay beliefs about the importance of various preferences and activities.

1239

MUSIC PREFERENCES

findings reinforce the importance of music as an everyday social

phenomenon and offer further justification for including music on

the research agenda for mainstream social and personality psy-

chology.

Mapping the Terrain of Music Preferences:

A Factor-Analytic Approach

The results of Study 1 indicate that people consider music to be

as important as other lifestyle and leisure activities. Having con-

firmed the importance of music in everyday life, the next step was

to identify the structure of music preferences. Three independent

studies were designed to identify the dimensions of music prefer-

ences and examine their generalizability across samples and meth-

ods. Study 2 was an exploratory analysis of music preferences.

Studies 3 and 4 served as confirmatory studies to test the gener-

alizability of the music-preference dimensions across time, sam-

ples, and methods.

Measuring Music Preferences

What is the most sensible unit of analysis for studying music

preferences? There are a variety of ways in which music prefer-

ences can be assessed. For example, individuals could report their

Figure 3. Lay beliefs about the amount of information various preferences and activities reveal about the

personality of oneself and others.

Figure 4. Self-reported frequency of listening to music in different situations.

1240

RENTFROW AND GOSLING

degree of liking for specific songs (e.g., “Born Blind”), bands or

artists (e.g., Sonny Boy Williamson), subgenres (e.g., harmonica

blues), genres (e.g., blues), or general music attributes (e.g., re-

laxed). Thus, music preferences could be measured at different

levels of abstraction, ranging from a highly descriptive subordinate

level to a very broad superordinate level (John, Hampson, &

Goldberg, 1991; Murphy, 1982).

What is the optimal level of abstraction with which to categorize

music? The focus of this research is on ordinary, everyday music

preferences, so our goal was to assess music preferences at the

level that naturally arises when people think about and express

their music preferences. When people discuss their music prefer-

ences they tend to do so first at the level of genres and to a lesser

extent subgenres and only later step up to broader terms (e.g., loud)

or down to specific artists (e.g., Van Halen) or songs (e.g., “Run-

ning with the Devil”; Jellison & Flowers, 1991). Thus, the genre

and subgenre categories were the optimal levels at which to start

our investigations of music preferences.

We used a multistep process to determine which genres and

subgenres to include in our measure of preferences. First, we

created a preliminary pool of music-preferences categories com-

prising music genres and subgenres. Specifically, we used a free-

association type task in which a panel of five judges was asked to

list all the music genres and subgenres that came to mind. Second,

to ensure that a variety of different styles of music were included,

we consulted with online music stores (e.g., towerrecords.com,

barnesandnoble.com) to identify additional genres and subgenres

to supplement the initial pool. This procedure generated a total

of 80 music genres and subgenres that varied in specificity. Next,

we presented these 14 genres and 66 subgenres to a group of 30

participants and asked them to indicate their preference for the

music categories usinga1(Not at all)to7(A great deal) rating

scale. Participants were instructed to skip any category with which

they were not familiar. Our analyses of items left blank showed

that very few participants (7%) were familiar with all of the

specific subgenres (e.g., Baroque, industrial, Western swing), but

nearly all of them (97%) were familiar with the broader music

genres (e.g., classical, heavy metal, country). These findings sug-

gested that the genre level was the appropriate level at which to

begin examining music preferences.

Thus, the final version, called the Short Test Of Music Prefer-

ences (STOMP), is made up of 14 music genres: alternative, blues,

classical, country, electronica/dance, folk, heavy metal, rap/hip-

hop, jazz, pop, religious, rock, soul/funk, and sound tracks. Pref-

erence for each genre is rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale with

endpoints at 1 (Not at all)and7(A great deal).

Study 2: An Exploratory Factor Analysis

of Music Preferences

The primary objective of Study 2 was to identify the basic

dimensions of music preferences. The study was exploratory and,

given the patchy literature on this topic, we had no a priori theories

or expectations about the number of dimensions or the nature of

the underlying structure. Instead, the analyses served as a spring-

board for generating theories and hypotheses regarding the nature

of music preferences. We used exploratory factor analysis to

examine the factor structure of music preferences; then, in a

subsample of participants, we examined whether the music dimen-

sions would generalize across time.

Method

Participants. The sample was made up of 1,704 University of Texas at

Austin undergraduates who volunteered in exchange for partial fulfillment

of an introductory psychology course requirement during the fall semester

of 2001. Of those who indicated, 1,058 (62.6%) were women and 633

(37.4%) were men, 62 (4.1%) were African American, 205 (13.5%) were

Asian, 205 (13.5%) were Hispanic, 988 (65%) were White, and 60 (3.9%)

were of other ethnicities.

Three weeks after the first sample was tested, a subsample of 118 of the

participants was tested again in exchange for partial fulfillment of an

introductory psychology course requirement. Of those who indicated, 94

(82%) were women and 21 (18%) were men, 6 (5.3%) were African

American, 25 (21.9%) were Asian, 11 (9.7%) were Hispanic, 64 (56.1%)

were White, and 8 (7%) were of other ethnicities.

Procedure. Participants completed the STOMP and a battery of per-

sonality measures during a massive testing session (Time 1). Participants

completed the STOMP again 3 weeks later (Time 2).

Results and Discussion

Factor structure. To identify the major dimensions of music

preferences, we performed principal-components analyses on par-

ticipants’ ratings. Determining the number of factors to retain is

critical in such analyses, because underextraction or overextraction

may distort subsequent findings (Zwick & Velicer, 1986). We

therefore used multiple converging criteria to decide on the ap-

propriate number of factors to retain: scree test (Cattell, 1966), the

Kaiser rule (i.e., eigenvalues of 1 or greater), parallel analyses of

Monte Carlo simulations (Horn, 1965), and the interpretability of

the solutions (see Zwick & Velicer, 1986). Following these crite-

ria, a four-factor solution was retained, which accounted for 59%

of the total variance.

In accord with Pedhauzer and Schmelkin (1991), both orthog-

onal (varimax) and oblique (oblimin) rotations were initially per-

formed. However, the two solutions were virtually identical, and

the mean correlation among the oblique factors was low (r ⫽ .01),

suggesting that the orthogonal solution offered a good fit for these

data.

As can be seen in the varimax-rotated factor loadings shown in

Table 1, the factor structure was very clear and interpretable, with

few cross-loading genres. Pop music was the only genre with

factor loadings greater than .40 on multiple factors. To determine

the best labels for the dimensions, seven psychologists (including

the two authors) examined the factor structure and consensually

generated labels to capture the main themes underlying the factors.

As in most factor-analytic research, broad labels inevitably capture

some factors better than others and should thus be used only as

guides to the content of each dimension.

The genres loading most strongly on Factor 1 were blues, jazz,

classical, and folk music—genres that seem to facilitate introspec-

tion and are structurally complex—and this factor was named

Reflective and Complex. Factor 2 was defined by rock, alternative,

and heavy metal music—genres that are full of energy and em-

phasize themes of rebellion—and was named Intense and Rebel-

lious. Factor 3 was defined by country, sound track, religious, and

pop music—genres that emphasize positive emotions and are

structurally simple—and was named Upbeat and Conventional.

1241

MUSIC PREFERENCES

Factor 4 was defined by rap/hip-hop, soul/funk, and electronica/

dance music—genres that are lively and often emphasize the

rhythm—and was named Energetic and Rhythmic.

Generalizability across time. The factor structure is clear, but

is it temporally stable? It is possible that the music individuals

enjoy listening to changes on a day-to-day basis, perhaps depend-

ing on the mood an individual is in. If so, the temporal stability of

music preferences should be quite low. Alternatively, music pref-

erences may be relatively stable, such that preferences for certain

genres do not vary on a day-to-day basis.

To address this issue, we determined the test–retest reliability of

the factors using the subsample of participants who completed the

STOMP again (at Time 2, approximately 3 weeks after the initial

testing session). For Times 1 and 2, we created unit-weighted

scales to measure each of the four varimax factors. Next, we

computed the correlation between Times 1 and 2 for each of the

four music dimensions. The results showed that preference for

each of the dimensions remained stable across time, with retest

rs ⫽ .77, .80, .89, and .82 for the Reflective and Complex, Intense

and Rebellious, Upbeat and Conventional, and Energetic and

Rhythmic dimensions respectively.

The results from this exploratory investigation suggest that there

is a clear underlying structure to music preferences. Four inter-

pretable factors were identified that capture a broad range of music

preferences. The results from the subsample of participants

tested 3 weeks after the first sample indicate that the music-

preference dimensions are reasonably stable. However, the analy-

ses were exploratory in nature, and a more stringent confirmatory

analysis was needed to test the generalizability of the structure

across samples. This was addressed in Study 3.

Study 3: Generalizability Across Samples

The purpose of this study was to test the cross-sample general-

izability of the dimensional structure of the music preferences

identified in Study 2. To address this issue, we used the same

procedure as in Study 2 and administered the STOMP to another

sample of college students.

Method

Participants. This sample was made up of 1,383 University of Texas

at Austin undergraduates who volunteered in exchange for partial fulfill-

ment of an introductory psychology course requirement during the spring

of 2002. Of those who indicated, 726 (59.7%) were women and 490

(40.3%) were men, 30 (2.5%) were African American, 225 (18.5%) were

Asian, 160 (13.2%) were Hispanic, 760 (62.6%) were White, and 39

(3.2%) were of other ethnicities. There was no overlap of participants

between Studies 2 and 3.

Procedure. The procedure used in Study 3 was identical to the one

used in Study 2. To assess music preferences, participants completed the

same version of the STOMP as participants in Study 2.

Results and Discussion

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). To examine the general-

izability of the four music-preference dimensions, we performed a

CFA on the music-preference data using LISREL (Jo¨reskog &

So¨rbom, 1989). CFA is a special type of factor analysis in which

hypotheses regarding the number of factors, their interrelations,

and the variables that load onto each factor can be specified and

tested. On the basis of the four orthogonal factors identified in

Study 2, we tested two models to permit a strong test of the

music-preference dimensions: one model in which the factors were

independent and one model in which the factors were allowed to

correlate. In both models, we specified four latent factors repre-

senting the four music dimensions: All the genres that loaded onto

each of the respective factors identified in Study 2 were freely

estimated. In Model 1, the intercorrelations of the latent factors

were set to zero, whereas in Model 2, this constraint was freed.

Evaluation of the fit of each model was based on multiple

Table 1

Factor Loadings of the 14 Music Genres on Four Varimax-Rotated Principal Components in

Study 2

Genre

Music-preference dimension

Reflective

and Complex

Intense

and Rebellious

Upbeat

and Conventional

Energetic

and Rhythmic

Blues .85 .01 ⫺.09 .12

Jazz .83 .04 .07 .15

Classical .66 .14 .02 ⫺.13

Folk .64 .09 .15 ⫺.16

Rock .17 .85 ⫺.04 ⫺.07

Alternative .02 .80 .13 .04

Heavy metal .07 .75 ⫺.11 .04

Country ⫺.06 .05 .72 ⫺.03

Sound tracks .01 .04 .70 .17

Religious .23 ⫺.21 .64 ⫺.01

Pop ⫺.20 .06 .59 .45

Rap/hip-hop ⫺.19 ⫺.12 .17 .79

Soul/funk .39 ⫺.11 .11 .69

Electronica/dance ⫺.02 .15 ⫺.01 .60

Note. N ⫽ 1,704. All factor loadings ⱍ.40ⱍ or larger are in italics; the highest factor loadings for each dimension

are listed in boldface type.

1242

RENTFROW AND GOSLING

criteria (Benet-Martı´nez & John, 1998; Bentler, 1990; Loehlin,

1998).

2

The results indicated that although Model 1, the orthogonal

model, did provide a reasonable fit,

2

(77, N ⫽ 1,383) ⫽ 812.3

(GFI ⫽ .92, AGFI ⫽ .89, RMSEA ⫽ .09, SRMR ⫽ .09), Model 2,

which allowed for correlated factors, fit significantly better,

⌬

2

(6) ⫽ 185.6, p ⬍ .001;

2

(71, N ⫽ 1,383) ⫽ 626.69 (GFI ⫽

.94, AGFI ⫽ .91, RMSEA ⫽ .07, SRMR ⫽ .06). As shown in

Figure 5, the intercorrelations among the music-preference dimen-

sions were relatively small, with only one (Upbeat and Conven-

tional with Energetic and Rhythmic) exceeding .20. Furthermore,

the factor loadings for all of the music genres were in the expected

direction. In short, the cross-sample congruence of the music-

preference dimensions identified in Study 2 and the CFA fit from

this study provide compelling evidence for the existence of four

music-preference dimensions.

Limitations. Although the results from the CFA provide sup-

port for the cross-sample generalizability of the music-preference

dimensions, two potential limitations undermine the generalizabil-

ity of the model. First, participants’ music preferences were de-

rived from self-reports. In theory, people know what they like and

what they do not like. However, relying exclusively on self-reports

of music preferences assumes that people are able to accurately

report on their preferences and fails to control for the potential

biases produced by impression-management motivations. An in-

dividual may enjoy listening to country music but might report no

preference for it if listening to country is considered “uncool.”

Second, our participants were attending a public university in

central Texas, a hotbed of country music, which raises concerns

about the generalizability of the results to other geographic re-

gions. It is not clear how Southern culture might influence partic-

ipants’ preferences. Would a similar music factor structure be

obtained among native New Yorkers, or even college students

living in New York City? Thus, it could be premature to conclude

that the music-preference dimensions identified in Studies 2 and 3

generalize across samples. To address these two limitations it is

necessary to examine music preferences using a methodology that

is not dependent on self-reports and does not oversample from a

particular geographic region. Study 4 was designed to address

these limitations.

2

A widely used fit index is the chi-square statistic. For small sample

sizes, a satisfactory fit is obtained when chi-square is approximately equal

to its degrees of freedom. However, the chi-square statistic is very sensitive

to sample size such that, when the sample size is large, slight discrepancies

in fit can lead one to reject an otherwise good-fitting model. Thus, for large

sample sizes researchers are encouraged to use additional indices to eval-

uate the fit of a model (Bentler, 1990; Loehlin, 1998). Widely used

alternatives include the goodness-of-fit index (GFI), the adjusted goodness-

of-fit index (AGFI), the root-mean-square error of approximation (RM-

SEA), and the standardized root-mean-square residual (SRMR). A RM-

SEA less than .10 reflects a good-fitting model and a value less than .05 an

excellent-fitting model (Steiger, 1989). According to Hu and Bentler

(1999), an SRMR less than .08 reflects a good-fitting model (for a detailed

review of the various fit indices, see Loehlin, 1998).

Figure 5. Standardized parameter estimates for Model 2 of the music-preference data in Study 3.

2

(71,

N ⫽ 1,383) ⫽ 626.69; goodness-of-fit index ⫽ .94; adjusted goodness-of-fit index ⫽ .91; root-mean-square error

of approximation ⫽ .07; standardized root-mean-square residual ⫽ .06. e ⫽ error variance.

1243

MUSIC PREFERENCES

Study 4: Generalizability Across Samples, Methods, and

Geographic Regions

Recently, a number of online Web sites (e.g., audiogalaxy.com,

kazaa.com, morpheus.com, napster.com) have sprung up to allow

individuals to share and download music from the Internet. One

feature offered by some of these Web sites is the ability to view the

music libraries of individuals using the Web site. At the time this

research was conducted, one such music provider (audiogalaxy

.com) had a list of all of the users currently online around the

globe. For the United States, users were organized by state. Each

user was then linked to a separate page that contained a list of all

the songs that the user had downloaded since joining the site. The

lists represent behaviorally revealed preferences of individuals

across the country and are ideally suited to address the limitations

of Studies 2 and 3.

Method and Procedure

We used the features offered by audiogalaxy.com to survey the music

collections of people from around the United States. We downloaded the

music libraries of individuals from each of the 50 states and then catego-

rized the songs in each person’s music library into music genres. To ensure

full geographic representation of music preferences within the United

States, 10 users from each state were randomly selected. Thus, the total

sample was composed of 500 individuals. Many of the users had only a few

songs in their music libraries, making it hard to obtain reliable estimates of

their music preferences. Therefore, we implemented a minimum criterion

of at least 20 songs. The number of songs in the remaining music libraries

ranged from 20 to over 500 songs. To ensure equal impact, we randomly

selected 20 songs from each eligible user’s music library, regardless of how

many songs were in their music library.

The 500 music libraries were divided among a group of seven judges so

that six judges had 70 libraries each and one had 80. Judges were then

trained to code the songs in each user’s music library into one of the 14

music genres covered in the STOMP: alternative, blues, classical, country,

electronica/dance, folk, heavy metal, rap/hip-hop, jazz, pop, religious,

rock, soul/funk, and sound tracks. If judges were unfamiliar with a song in

a participants’ music library, they consulted with towerrecords.com or with

another judge to determine the appropriate genre. In instances in which the

appropriate genre of a song could not be determined by these means, the

song was not included in the analyses.

A user’s preference for a particular genre of music was determined by

the number of songs that appeared in each music genre. Thus, scores for

each of the genres could range from 0 (No preference)to20(Strong

preference). Because there were almost as many music categories as there

were songs for each user, a large number of the music categories contained

zeros. Consequently, the distribution of the music-preference data was

negatively skewed and corrected using Poisson transformations.

The only available information for each user was their username and the

songs in their music library, so we could not determine their gender or age.

However, according to the marketing department for a similar online music

Web site, approximately 60% of online music users are men and 40% are

women, and the average age of users is 25 years (sales department of

kazaa.com, personal communication, July 5, 2002).

3

Results and Discussion

To examine the generalizability of the music-preference dimen-

sions across methods and populations, we performed a CFA on the

audiogalaxy.com data using LISREL (Jo¨reskog & So¨rbom, 1989).

As in Study 3, we tested two models, one in which the factors were

specified as orthogonal and one in which the factors were allowed

to correlate. In both models, we specified four latent factors

representing the four music dimensions: All the genres that loaded

onto each of the respective factors identified in Study 2 were freely

estimated.

The results indicated that although Model 1, the orthogonal

model, provided a reasonable fit,

2

(77, N ⫽ 500) ⫽ 176.31

(GFI ⫽ .95, AGFI ⫽ .93, RMSEA ⫽ .05, SRMR ⫽ .06), Model 2,

which allowed for correlated factors, fit significantly better,

⌬

2

(6) ⫽ 39.27, p ⬍ .001;

2

(71, N ⫽ 500) ⫽ 137.05 (GFI ⫽ .96,

AGFI ⫽ .94, RMSEA ⫽ .04, SRMR ⫽ .05). As shown in Figure 6,

the intercorrelations among the music-preference dimensions were

generally small, with only one (Reflective and Complex with

Energetic and Rhythmic) exceeding .20. Furthermore, the factor

loadings for the music genres were generally strong, and all were

in the expected direction.

In sum, three separate studies of over 3,500 participants con-

verged on the finding that music preferences can be organized into

four independent dimensions: Reflective and Complex, Intense

and Rebellious, Upbeat and Conventional, and Energetic and

Rhythmic. Although the age range of the audiogalaxy.com sample

was probably not as broad as we had hoped, the convergent

findings provided strong evidence for the generalizability of the

music-preference dimensions. These dimensions generalized

across time, populations, method, and geographic region.

Study 5: Understanding the Music Dimensions

After we had identified some robust music-preference dimen-

sions, the next task was to identify the qualities that define them:

What are the common threads that hold these factors together?

Why do preferences for certain genres of music cluster together?

The attributes of music vary across a wide range of moods, energy

levels, complexities, and lyrical contents. For example, some

genres emphasize negative emotions (e.g., heavy metal), whereas

others emphasize positive emotions (e.g., religious); some genres

are technically complex (e.g., classical), whereas others tend to be

basic (e.g., country); some genres have relatively few songs with

vocals (e.g., jazz), whereas others only have songs with vocals

(e.g., pop). Thus, the objective of Study 5 was to systematically

examine the attributes of the four music-preference dimensions.

Method

Examining the properties of the music dimensions involved three steps.

First, we selected songs that exemplified the music genres defining each of

the music-preference dimensions. Second, we generated a set of specific

music attributes on which the exemplar songs could be judged. Third, a

group of judges independently rated the exemplar songs on each of the

music attributes.

Exemplar song selection. To determine the defining attributes of each

of the music-preference dimensions, we selected a sample of songs that

could serve as stimuli for judges to rate. Specifically, we selected songs to

serve as exemplars for the 14 music genres used in the previous studies:

alternative, blues, classical, country, electronica/dance, folk, heavy metal,

3

Audiogalaxy.com did not respond to our requests for the demographic

information of their subscribers. Therefore, we report here information

furnished by a similar online music provider (kazaa.com), which was

willing to provide us with general demographic information about online

music users.

1244

RENTFROW AND GOSLING

hip-hop/rap, jazz, pop, religious, rock, soul, and funk. Sound track music

was excluded because sound tracks can contain the musical styles of

practically every other music genre; in other words, there were extremely

few specific songs that were more prototypical of sound tracks than of

other genres.

Some songs blend styles from different genres, so it was necessary that

each song exemplify only one genre. To ensure this, we consulted with

various online music providers (e.g., towerrecords.com, audiogalaxy.com)

to identify the exemplar songs of each of the respective genres. Many

online music providers display “essential” compilation albums for a variety

of music genres. The essentialness of each recording is based on either the

number of units sold, customer recommendations, or reviews by music

critics. Using these resources, we created a pool of approximately 25

possible songs for each of the 14 music genres. Selecting only one

exemplary song as an index of a whole genre would not provide a very

reliable estimate of the characteristics of the genre or sufficient content

validity. To improve the content validity of the sets of songs representing

each genre, we selected 10 exemplary songs that represented a broad array

of styles, artists, and time periods within each genre. This process resulted

in a total of 140 songs (see Appendix for a list of the songs).

Music attribute selection. To select the music attributes, we used a

multistep procedure similar to the one described by Aaker, Benet-Martı´nez,

and Garolera (2001) to select commercial brands. Songs are often de-

scribed using terms that are also used to describe people (e.g., complex,

emotional, cheerful, reflective). Therefore, we began our item-selection

procedure with the pool of 300 person descriptors in the Adjective Check

List (ACL; Gough & Heilbrun, 1983). Usinga1(relevant)to3(irrelevant)

rating scale, three expert judges independently rated each of the 300 ACL

adjectives for their relevance in describing various aspects of music. All

attributes that were considered at least somewhat relevant (i.e.,a2onthe

scale) by at least two of the three judges were retained, resulting in an

initial pool of 130 attributes.

To increase the range of music attributes and to test the effectiveness of

the initial ACL-based procedures, a second step used a structured free-

description task in which four independent judges were asked to list all the

music attributes that came to mind while thinking about any and all types

of music. Using this procedure, only seven new attributes were identified

that had not been identified in the previous step; this finding was reassuring

because it underscored the effectiveness of the ACL-based item-generation

procedures.

In the third step, a separate group of seven judges independently eval-

uated the extent to which each attribute could be used to characterize

various aspects of music. Specifically, judges were instructed to first

indicate the extent to which each of the music attributes could be used to

describe various aspects of the music and/or the lyrics using a 5-point scale

(1 ⫽ Not at all;5⫽ Definitely), then to indicate which aspect of the music

the attribute best described using a three-valued categorization system (i.e.,

L ⫽ only the lyrics, B ⫽ both the lyrics and music, M ⫽ only the music).

For example, if reflective was considered useful in describing a particular

aspect of music it might be given a 4, and if it was thought to be

characteristic of the lyrics only it would get an L.

The number of potential music attributes was very large, so we used a

high-relevance threshold (4.5 or higher) to ensure inclusion of only the

most relevant attributes. This strategy resulted in a list of 20 attributes:

clever, dreamy, relaxed, enthusiastic, simple, pleasant, energetic, loud,

cheerful/happy, uplifting, angry, depressing/sad, emotional, romantic,

rhythmic, frank/direct, boastful, optimistic, reflective, and bitter. Because

the expert judges used person descriptors as a starting point for generating

music attributes, a few important general musical attributes, such as tempo

(e.g., fast, slow) and mode (e.g., acoustic, electric), did not appear on the

Figure 6. Standardized parameter estimates for Model 2 of the music-preference data in Study 4.

2

(71, N ⫽

500) ⫽ 137.05; goodness-of-fit index ⫽ .96; adjusted goodness-of-fit index ⫽ .94; root-mean-square error of

approximation ⫽ .04; standardized root-mean-square residual ⫽ .05. e ⫽ error variance.

1245

MUSIC PREFERENCES

list. Thus, we supplemented the 20 attributes with an additional 5 attributes

(fast, slow, acoustic, electric, and voice) for a final list of 25 music

attributes.

Procedure. A group of seven judges, representing a variety of musical

tastes, independently rated the songs on the attributes. The 140 songs were

compiled onto CDs. The songs on the CDs were grouped by genre. To

reduce the impact of order effects, two sets of CDs that differed in song

order were created. Judges were unaware of the purpose of the study and

were simply instructed to listen to each song in its entirety, then to rate each

song on each of the music and lyric attributes using a 7-point scale with

endpoints at 1 (Extremely uncharacteristic)and7(Extremely characteris-

tic). For songs with no lyrics, judges were instructed to leave the lyric

attributes blank; there were 25 songs with no lyrics. Our analyses of

structure in Studies 2–4 were based on music preferences of ordinary

persons, so for this study, too, we were interested in ordinary persons’

impressions of music (rather than the impressions of trained musicians).

Thus, judges were given no specific instructions about what information

they should use to make their judgments.

Results and Discussion

Reliability. To evaluate the reliability of judges’ attribute rat-

ings of the songs, Cronbach’s alphas were computed across songs

for each attribute. In general, reliability was high. As can be seen

in Table 2, inter-rater reliability was highest for the general at-

tributes (M

␣

⫽ .90), followed by the music and lyric attributes

(Ms ⫽ .79, .79). Overall, the coefficients ranged from .43 for

ratings of the rhythm of the lyrics to .93 for the amount of singing.

Interestingly, reliability for some of the more metaphorical at-

tributes such as sad, angry, depressing, bitter, happy, relaxed, and

romantic was at least as high as more observable, literal attributes

such as whether the song was acoustic, electric, fast, or slow.

Distinguishing the music-preference dimensions. What are the

attributes that distinguish the music-preference dimensions? To

examine how the music dimensions differed in terms of musical

attributes, we performed analyses of variance (ANOVAs) on each

of the attributes within the three music-attribute categories (gen-

eral, lyrical, and musical), using music dimension as the indepen-

dent variable.

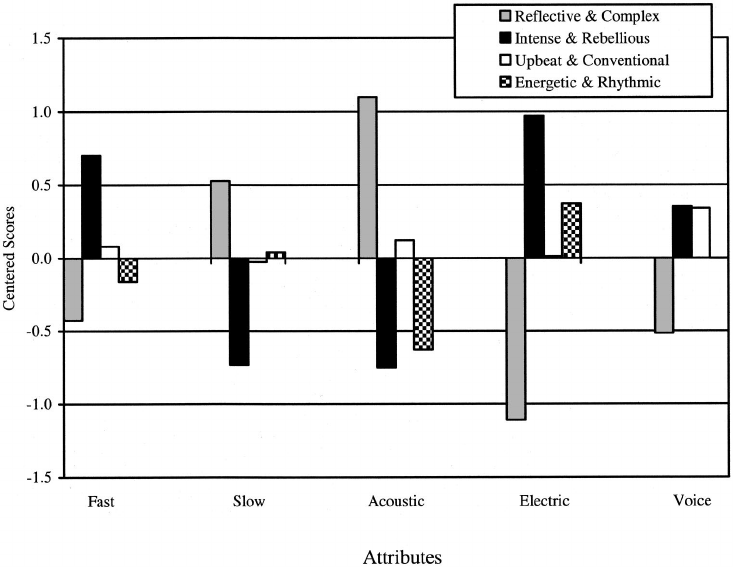

How did the music dimensions differ in terms of general at-

tributes? As shown in Figure 7, the music dimensions were sig-

nificantly different across the five general attributes; Fs(3, 136)

ranged from 6.68 to 67.13, all ps ⬍ .001. In general, the Reflective

and Complex music dimension was slower in tempo than the other

dimensions, used mostly acoustical instruments, and had very little

singing. The Intense and Rebellious dimension was faster in

tempo, used mostly electric instruments, and had a moderate

amount of singing. The Upbeat and Conventional dimension was

moderate in tempo, used both acoustic and electric instruments,

and had a moderate amount of singing. The Energetic and Rhyth-

mic dimension was also moderate in tempo, used electric instru-

ments, and had a moderate amount of singing.

How did the music dimensions differ in terms of lyrical at-

tributes? As shown in Figure 8, the music dimensions were sig-

nificantly different across all of the lyric attributes except rhyth-

mic; all statistically significant Fs(3, 128) ranged from 4.10

to 33.02, ps ⬍ .01. For presentational clarity, the lyric attributes

were divided into four general categories: complexity (e.g., simple,

clever), positive affect (e.g., cheerful/happy, romantic), negative

affect (e.g., depressing/sad, angry), and energy level (e.g., relaxed,

energetic). In general, the lyrics in the Reflective and Complex

dimension were perceived to be complex, to express both positive

and negative emotions, and to have a low level of energy. The

Intense and Rebellious dimension was perceived to be moderately

complex, low in positive affect, but high in negative affect and

energy level. The lyrics in the Upbeat and Conventional dimension

were perceived as simple and direct, low in negative affect, but

high in positive affect and energy level. The lyrics in the Energetic

and Rhythmic dimensions were perceived as being somewhat

complex, unemotional, and moderate in energy level.

How do the music dimensions differ in terms of musical at-

tributes? As shown in Figure 9, the music dimensions were sig-

nificantly different across the 15 music attributes; Fs(3, 136)

ranged from 3.06 to 46.08; ps ⬍ .05. For presentational clarity, we

again divided the attributes into four general categories: complex-

ity, positive affect, negative affect, and energy level. The musical

attributes of the Reflective and Complex dimension were per-

ceived as complex, high in both positive and negative affect, yet

low in energy level. As with the lyric attributes of the Intense and

Rebellious dimension, the music attributes were perceived as mod-

erately complex, low in positive affect, and high in both negative

affect and energy level. The music attributes of the Upbeat and

Conventional dimension were perceived as simple and direct,

moderately high in positive affect, and low in both negative affect

and energy level. The music attributes of the Energetic and Rhyth-

mic dimension were perceived as moderately complex, unemo-

tional, and moderate in energy level.

Table 2

Interrater Reliability (Coefficient Alpha) of Judges’ Ratings of

the Music Attributes

Attribute

Music attribute category

General

(M ⫽ 0.90)

Lyrics

(M ⫽ 0.79)

Music

(M ⫽ 0.79)

Fast 0.90

Slow 0.89

Acoustic 0.87

Electric 0.89

Voice 0.93

Frank/direct 0.62

Boastful 0.80

Optimistic 0.83

Reflective 0.62

Bitter 0.87

Clever 0.64 0.66

Dreamy 0.82 0.85

Relaxed 0.85 0.88

Enthusiastic 0.73 0.77

Simple 0.66 0.70

Pleasant 0.70 0.70

Energetic 0.84 0.86

Loud 0.84 0.85

Cheerful/happy 0.86 0.83

Uplifting 0.82 0.70

Angry 0.91 0.90

Depressing/sad 0.87 0.82

Emotional 0.85 0.78

Romantic 0.88 0.86

Rhythmic 0.43 0.45

Note. Means were calculated using Fisher’s r-to-z transformation. Blank

cell indicates that no data were collected for this attribute in this category.

1246

RENTFROW AND GOSLING

Summary

Overall, the judges’ ratings of the 140 songs shed light on the

underlying attributes that bind music genres together. In addition,

they suggest that the dimension labels we chose in Study 2 char-

acterize each dimension quite well. Analyses of the music at-

tributes paint rather interesting and unique pictures of each dimen-

sion. Whereas the Reflective and Complex dimension projects a

broad spectrum of both positive and negative emotions that is quite

complex in structure, the Intense and Rebellious dimension dis-

plays moderately complex structure and intense negative emotions.

The Upbeat and Conventional dimension expresses predominantly

positive emotions, is simple in structure, and is moderately ener-

getic, whereas the Energetic and Rhythmic dimension exhibits

comparatively less positive and negative emotion, is moderately

energetic, and tends to place greater emphasis on rhythm.

Study 6: Examining the Relationship Between Music

Preferences and Personality

In Studies 2–4, we identified four dimensions of music prefer-

ences that generalized across time, populations, methods, and

geographic region. In Study 5, we characterized each dimension in

terms of a variety of different music attributes. Having identified

and characterized the music-preference dimensions, we could ad-

dress a central question underlying this research: How are music

preferences related to existing personality characteristics?

Method

Participants. To examine the external correlates of the four music-

preference dimensions, we administered a number of tests of personality,

self-views, and cognitive ability to a sample of college students. Partici-

pants were from Studies 2 and 3 and the retest subsample from Study 2

(Ns ⫽ 1,704, 1,383, and 118, respectively). In both Studies 2 and 3 (S2 and

S3), participants completed measures of personality and self-views, and

participants in the retest subsample (SS2) completed a test of cognitive

ability.

Measures of personality. Personality was assessed with a variety of

measures. To assess personality at a broad level, we included the Big Five

Inventory (BFI; John & Srivastava, 1999). The BFI consists of 44 items

that tap five broad personality domains. Items were rated on a 5-point scale

with endpoints at 1 (Disagree strongly)and5(Agree strongly).

The Personality Research Form—Dominance (Jackson, 1974) was ad-

ministered as a measure of interpersonal dominance strivings. Using a

true–false response format, participants indicated their agreement with 16

statements.

We included the Social Dominance Orientation Scale (Pratto, Sidanius,

Stallworth, & Malle, 1994). This questionnaire consists of 14 items, which

tap individual differences in orientation to socially conservative ideals and

attitudes. Participants were asked to indicate their feeling toward each

statement using a 7-point Likert-type scale with endpoints at 1 (Very

negative)and7(Very positive).

The Brief Loquaciousness and Interpersonal Responsiveness Test

(Swann & Rentfrow, 2001) was administered to assess individual differ-

ences in interpersonal communication styles. Specifically, this test discrim-

inates between individuals who tend to express their thoughts and feelings

as soon as they come to mind (blirtatious [from the acronym for the test,

BLIRT] individuals) and individuals who tend to keep their thoughts to

themselves (nonblirtatious individuals). Participants indicated the extent to

which they agreed with eight items using a 5-point scale with endpoints

at1(Strongly disagree)and5(Strongly agree).

Self-esteem was assessed with the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosen-

berg, 1965). This is a widely used measure of self-esteem and consists

of 10 statements. Participants were asked to indicate, using a 5-point

Figure 7. General attributes of each of the music-preference dimensions.

1247

MUSIC PREFERENCES

Likert-type scale with endpoints at 1 (Not at all)and5(Extremely) the

extent to which each statement was characteristic of themselves.

The Beck Depression Inventory (Beck, 1972) was included as a measure

of depression. This test assesses individual differences in depression and

captures the degree to which individuals have experienced depressive

thoughts and feelings during the preceding week. Participants responded

to 13 items, each with four statements, and indicated which statement best

described their feelings over the past week.

Self-views. We were also interested in how individuals’ self-views

relate to their music preferences. Using a 5-point Likert-type scale with

endpoints at 1 (Disagree strongly)and5(Agree strongly), participants

were asked to indicate the extent to which they saw themselves as politi-

cally liberal, politically conservative, physically attractive, wealthy, ath-

letic, and intelligent.

Cognitive ability. The Wonderlic IQ Test (Wonderlic, 1977) was ad-

ministered as a measure of verbal and analytic reasoning ability. The test

includes 50 items, and participants were given 12 min to complete as many

items as possible. Research among college samples has found that the test

is predictive of college grades (McKelvie, 1989) and ratings of self-

perceived intelligence (Paulhus, Lysy, & Yik, 1998).

Results and Discussion

To examine the relationship between music preferences and

personality, scale scores on each of the four dimensions were

computed. We then computed correlations between the music-

preference dimensions and scores on the measures of personality,

self-views, and cognitive ability. The patterns of correlations be-

tween the music-preference dimensions and the external correlates

are shown in Table 3.

4

The correlations presented in Table 3 reveal a fascinating pat-

tern of links between music preferences and personality, self-

views, and cognitive ability. For example, the Reflective and

Complex dimension was positively related to Openness to New

Experiences, self-perceived intelligence, verbal (but not analytic)

ability, and political liberalism and negatively related to social

dominance orientation and athleticism. These correlations, along

with item-level analyses of the BFI, suggest that individuals who

enjoy listening to reflective and complex music tend to be inven-

tive, have active imaginations, value aesthetic experiences, con-

sider themselves to be intelligent, tolerant of others, and reject

conservative ideals.

4

Research with musicians has suggested that men and women prefer to

play different musical instruments (Dibben, 2002; O’Neill, 1997; O’Neill

& Boulton, 1996), so it is reasonable to suppose that the relationships

between music preferences and personality could be moderated by sex.

However, when correlations between music preferences and personality

were computed separately for men and women, the magnitude and pattern

of the correlations were virtually identical for both sexes. Thus, the

correlations presented in Table 3 include both men and women.

Figure 8. Lyric attributes of each of the music-preference dimensions.

1248

RENTFROW AND GOSLING

The Intense and Rebellious dimension was positively related to

Openness to New Experiences, athleticism, self-perceived intelli-

gence, and verbal ability. Interestingly, despite previous findings

that this dimension contains music that emphasizes negative emo-

tions, individuals who prefer music in this dimension do not appear

to display signs of neuroticism or disagreeableness. Overall, indi-

viduals who prefer intense and rebellious music tend to be curious

about different things, enjoy taking risks, are physically active, and

consider themselves intelligent.

The external correlates of the Upbeat and Conventional dimen-

sion reveal positive correlations with Extraversion, Agreeableness,

Conscientiousness, conservatism, self-perceived physical attrac-

tiveness, and athleticism and negative correlations with Openness

to New Experiences, social dominance orientation, liberalism, and

verbal ability. Our analyses suggest that individuals who enjoy

listening to upbeat and conventional music are cheerful, socially

outgoing, reliable, enjoy helping others, see themselves as physi-

cally attractive, and tend to be relatively conventional.

The Energetic and Rhythmic dimension was positively related

to Extraversion, Agreeableness, blirtatiousness, liberalism, self-

perceived attractiveness, and athleticism and negatively related to

social dominance orientation and conservatism. Thus, individuals

who enjoy Energetic and Rhythmic music tend to be talkative, full

of energy, are forgiving, see themselves as physically attractive,

and tend to eschew conservative ideals.

As one would expect for such a broad array of constructs, the

magnitude of correlations varied greatly. To test the generalizabil-

ity of the correlations across samples, we computed column–vector

correlations for each of the four dimensions. Specifically, we

transformed the correlations using Fisher’s r-to-z formula and then

computed the correlation between the two columns of transformed

correlations. As shown in the bottom row of Table 3, the pattern of

correlations for each of the music dimensions was virtually iden-

tical across samples; column–vector correlations ranged from .851

for the Energetic and Rhythmic dimension to .977 for the Reflec-

tive and Complex dimension.

5

One noteworthy finding was the absence of substantial correla-

tions between the music-preference dimensions and Emotional

Stability, depression, and self-esteem, suggesting that chronic

emotional states do not have a strong effect on music preferences.

Within each music dimension, however, there are undoubtedly

songs that capture different emotional states. Therefore, the fact

that no relationship was found between music preferences and

chronic emotions does not indicate that emotions are not related to

5

It should be noted that strong column–vector correlations could be

generated merely from the inclusion of a mixture of constructs, some of

which correlate strongly and some of which correlate weakly with the

music-preference dimensions.

Figure 9. Music attributes of each of the music-preference dimensions.

1249

MUSIC PREFERENCES

music preferences. One possibility is that existing personality

dimensions influence the music-preference dimensions that indi-

viduals generally prefer and that emotional states influence the

“mood” of the music that individuals choose to listen to on any

given day. To gain a firm grasp of the link between music pref-

erences and emotions, future research should examine the emo-

tional valence of the music people choose to listen to while in

different emotional states.

General Discussion

The primary purpose of this research was to examine the land-

scape of music preferences, thereby laying the groundwork for a

theory of music preferences. In a series of studies, we examined

lay beliefs about music, the structure underlying music prefer-

ences, and the links between music preferences and personality.

One goal of this research was to determine how much importance

individuals give to music relative to other leisure activities. Over-

all, the results from Study 1 indicate that music is at least as

important as most other leisure activities. Participants believed that

their music preferences revealed a substantial amount of informa-

tion about their own personalities and self-views and the person-

alities of other people. Furthermore, participants reported listening

to music very frequently in a variety of different contexts. These

latter findings converge nicely with recent work by Mehl and

Pennebaker (2003), who sampled people’s everyday activities and

found that individuals listened to music during approximately 14%

of their waking lives, roughly the same amount of time as they

spent watching television and half the amount of time they spent

engaged in conversations. Thus, our data support empirically what

might seem self-evident to many: Music is important to people,

and they listen to it frequently.

Using multiple samples, methods, and geographic regions, three

independent studies converged to reveal four dimensions of music

preferences. The findings presented in Studies 2–4 are important

because they are the first to suggest that there is a clear, robust, and

meaningful structure underlying music preferences. In addition,

the results from Study 5 provide valuable information about the

music attributes that differentiate the music-preference dimen-

sions: The dimensions can be distinguished by their levels of

complexity, emotional valence, and energy level.

Although early research on music preferences suggested links

between certain music genres and certain personality characteris-

Table 3

External Correlates of the Music-Preference Dimensions

Criterion measure M (SD)

Reflective and

Complex

Intense and

Rebellious

Upbeat and

Conventional

Energetic and

Rhythmic

S2 S3 S2 S3 S2 S3 S2 S3

Personality

Big Five

Extraversion 3.42 (0.85) .01 ⫺.02 .00 .08* .24* .15* .22* .19*

Agreeableness 3.80 (0.62) .01 .03 ⫺.04 .01 .23* .24* .08* .09*

Conscientiousness 3.57 (0.64) ⫺.02 ⫺.06 ⫺.04 ⫺.03 .15* .18* .00 ⫺.03

Emotional Stability 3.11 (0.81) .08* .04 ⫺.01 ⫺.01 ⫺.07 ⫺.04 .01 ⫺.01

Openness 3.75 (0.61) .44* .41* .18* .15* ⫺.14* ⫺.08* .03 .04

Interpersonal dominance 1.52 (0.25) .07* .06* .04 .06* .05 .08* .04 .05

Social dominance 2.70 (1.00) ⫺.16* ⫺.12* .06* .04 ⫺.06* ⫺.14* ⫺.09* ⫺.10*

Blirtatiousness

a

2.95 (0.70) .00 .00 .01 .07* ⫺.04 .01 .08* .11*

Self-esteem 3.05 (0.69) .02 .00 ⫺.02 ⫺.01 .07* ⫺.05 .06* ⫺.04

Depression 0.87 (0.34) .01 ⫺.03 .03 .03 ⫺.08* ⫺.07* ⫺.02 .04

Self-views

Politically liberal 3.17 (1.22) .15* .09* .03 .08* ⫺.20* ⫺.17* .07* .14*

Politically conservative 2.83 (1.21) ⫺.09* ⫺.03 ⫺.04 ⫺.03 .24* .23* ⫺.06* ⫺.09*

Physically attractive 3.69 (0.91) .00 ⫺.03 ⫺.04 ⫺.05 .07* .09* .15* .08*

Wealthy 2.86 (1.11) ⫺.04 ⫺.06 ⫺.03 .00 .08* .05 .02 ⫺.01

Athletic 3.33 (1.26) ⫺.07* ⫺.08* .06* .07* .13* .12* .11* .07*

Intelligent 4.22 (0.71) .10* .06* .07* .08* ⫺.05* ⫺.02 ⫺.02 .01

Cognitive ability (Wonderlic)

b

Verbal 19.09 (3.72) .19* — .19* — ⫺.18* — ⫺.01 —

Analytical 6.11 (2.16) .08 — .05 — .02 — ⫺.08 —

Column vector correlations .977 .863 .923 .851

Note. Ns ⫽ 1,704, 1,383, and 118 for S2, S3, and SS2, respectively. Means and standard deviations are averaged across samples. Dashes in cells indicate

data were not collected. S2 ⫽ sample from Study 2; S3 ⫽ sample from Study 3; SS2 ⫽ sub-sample from Study 2.

a

Blirtatiousness ⫽ tendency to express thoughts and feelings as soon as they come to mind (from the acronym for the Brief Loquaciousness and

Interpersonal Responsiveness Test [BLIRT]; see Swann & Rentfrow, 2001).

b

SS2.

* p ⬍ .05.

1250

RENTFROW AND GOSLING

tics, the picture they provided was not complete. Using a broad and

systematic selection of music genres and personality dimensions,

the results from Study 6 cast more light on the variables that link

individuals to their music of choice. Across two samples of college

students, relationships between music preferences and existing

personality dimensions, self-views, and cognitive abilities were

identified.

Developing a Theory of Music Preferences

The research reported here fits into a broader agenda of devel-

oping a theory of music preferences. What should be asked of such

a theory? One important question pertains to the formation of

music preferences. How do music preferences develop? What

factors influence their development? A second question relates to

the trajectory of music preferences. How, when, and why do music

preferences change? A theory of music preferences should also

address the impact of music on behavior. How do music prefer-

ences influence behavior and how do individuals make use of

music in their everyday lives?

The research presented here indicates that personality, self-

views, and cognitive abilities could all have roles to play in the

formation and maintenance of music preferences. The results from

Study 6 are consistent with the idea that personality has an impact

on music preferences. Just as the social and physical environments

that people select and shape reflect their personalities (Buss, 1987;

Gosling et al., 2002; Snyder & Ickes, 1985), so too do their

musical environments. Our findings show that, for example, pref-

erence for cheerful music with vocals (the Upbeat and Conven-

tional dimension) was positively related to Extraversion whereas

preference for artistic and intricate music (e.g., the Reflective and

Complex dimension) was positively related to Openness to New

Experiences. Future research that includes narrower facets of per-

sonality is needed to provide a finer grained picture of the effects

of personality on music preferences.

Music preferences also appear to be shaped by self-views.

Theorists concerned with social identity and the self have pointed

out that the social environments that individuals select serve to

reinforce their self-views (e.g., Gosling et al., 2002; Swann, 1987,

1996; Swann et al., 2002; Tajfel & Turner, 1986), and our findings

suggest that people may select music for similar reasons. This can

happen in two ways. First, music preferences could be used to

make self-directed identity claims (Gosling et al., 2002). That is,

individuals might select styles of music that reinforce their self-

views; for example, individuals may listen to esoteric music to

reinforce a self-view of being sophisticated. Our findings provide