Stephanie Chisolm:

Early stage tumors in non-muscle invasive bladder cancer, or NMIBC, are generally confined to the lining

of the bladder, and they may be papillary and look a little bit like tiny finger-like clusters or flat, velvety

patches known as carcinoma in situ or CIS. Tumors that are CIS have a very high rate of recurrence and

possible disease progression, so it's really helpful to understand your diagnosis. Tonight, BCAN is

welcoming urologist Peter Black from the Vancouver General Hospital in Canada and Pathologist Dr.

Hikmat Al-Ahmadie from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York City. We're delighted to

have you here to help us talk about CIS and what patients need to know. So welcome to both of you. I'm

going to turn my video off, and Dr. Black, if you want to take it away.

Dr. Peter Black:

Terrific. Thank you, Stephanie, very much

for the invitation and the opportunity. I

think I can speak for Hikmat as well, that

we're both passionate about bladder

cancer and so we're always very happy to

explain what we know and educate, so

hopefully the attendees tonight will find

this interesting. Hikmat and I are going to

go back and forth a little bit. I'll start and

then we'll switch to Hikmat and we'll carry

on like that. What is carcinoma in situ?

Stephanie alluded to it a little bit at the

beginning. We have this broad spectrum of

disease stages for bladder cancer from the

very superficial on the left and carcinoma

in situ is also called TIS. It's just right on the

surface of the bladder, to tumors that

actually extend into the lumen of the bladder but still sit on the surface. That's the Ta just next to that.

Then, the T1 tumors that are already invading the first layer of the bladder wall. Those three together

are all non-muscle invasive, but there's a difference between actually invasive T1 and the other two that

are really non-invasive. And then on the right, we have the muscle-invasive, which we're not going to

talk about this evening.

Dr. Peter Black:

There's special things about carcinoma

in situ that make it really worth having

a dedicated session just on this. So it's

a flat tumor, there's no tumor

extending into the lumen of the

bladder. It's often red and velvety, but

sometimes it's invisible, so we struggle

to see it in a lot of patients. Although

it's an early stage of bladder cancer, it

is high grade. By definition, it's always

high grade and therefore, it has a

significant malignant potential. It has

the potential to develop into muscle-

invasive bladder cancer, so even

though it's early stage, we take it very

seriously and we treat it quite

aggressively because we need to

eradicate it. One of the problems that

we also struggle with is that this

transition from a non-invasive,

superficial carcinoma in situ into a

potentially invasive muscle-invasive

tumor is very unpredictable.

Some other key features is that it's

often... if it's found together with the

other non-muscle invasive bladder

cancer stages, so Ta and T1, it indicates

a higher risk of recurrence and

progression. The fact that the cancer

could come back or it can turn into

something more invasive if there's

carcinoma in situ there. It's an

additional risk factor in patients who

have other disease stages.

Carcinoma in situ we assume is

multifocal, so it's at different locations

in the bladder, or even diffuse,

meaning anywhere you would sample

the bladder wall, you would find

carcinoma in situ. That's a very

important and special feature. The other tumors generally we consider to be confined to what we see

and what we resect. Because it's multifocal and diffuse, we general believe that we cannot resect it

completely with a transurethral resection, which again, is different from the other bladder tumors that

typically we can resect at least all visible disease.

Dr. Peter Black:

Since we can't resect it, we either need to treat it with intravesical therapy such as BCG, or we need to

remove the bladder if we really want to get rid of it all. That's why it's really tricky and a bit different

than the other bladder tumors.

I'm going to present a patient profile,

and then Hikmat and I will go back

and forth a little bit about some of the

issues related to this patient's bladder

cancer. So this patient is an 87-year-

old gentleman, retired chartered

accountant, who has been a longtime

smoker, more than 50 pack/year

history of smoking. He was found just

on a regular check with his primary

care provider to have red blood cells

in his urine under microscopy. He's

never seen blood himself, so there's

no gross hematuria, just microscopic

hematuria. He has symptoms that are

common for his age. Nothing

particularly severe or noteworthy,

extreme. He gets up a couple times at

night. There's some urgency to void.

He has very significant other health

issues. He has heart disease, diabetes,

high blood pressure, and he is even on home oxygen because he has emphysema also related to his

smoking history. One thing that is relatively clear when we look at this gentleman is that he's probably

not going to be fit from a general health point of view to undergo radical cystectomy to remove the

bladder. We're not necessarily at that point yet, but I just wanted to highlight that in his medical history.

His family doctor, based on the microhematuria and the risk factors, sent his urine for urine cytology.

Can you go back for a second? The diagnosis of the urine cytology is high grade urothelial carcinoma.

Hikmat's going to run us through a little bit what that means.

Dr. Hikmat Al-Ahmadie:

All right. Thank you, Peter for the lead-in and hello everyone. Thanks for tuning in and spending the

evening with us. It's my pleasure to share this hour with you and talk to you about urothelial carcinoma

in situ and different aspects of the disease, and hopefully you'll find it helpful. As the story started, a

quick test is urine sample. It's a very easy type of specimen to get. It just requires the urine sample that

you may get in the clinic or the office. It is sent to the pathology department. It's spun down, just to

concentrate the cells in that container, and then it will give us a better opportunity to detect any

atypical cells in there, and when slides are prepared, the tissue is stained, then we'll be able to have the

ability to visualize cells that can tell us what they constitute, they're benign or reactive or abnormal cells,

and we follow a system. There is a system.

These type of specimens have been

studied for a long time and there

are criteria that we apply every time

we analyze these type of samples.

And then we follow the most recent

system is the Paris System, and it

has different categories and every

case, every urine sample that goes

to the lab, the result come back

with one of these categories. Of

course the red flag would be, or

when we highly suspect a urothelial

carcinoma is in these two categories

that are in bold now, the number

four and five. Either we see some

atypical cells that are atypical

enough to suspect urothelial

carcinoma but there are not as

many of them as you would want.

The cutoff has been made as 10

cells. If you see more than 10 cells

that are very atypical, and I'm going to show in some of these features what we mean by atypical in the

next slide, these are what you say suspicious. When you see these atypical cells in a quantity that is high

enough, and as I said, this is typically more than 10 cells, then you can render the diagnosis of high grade

urothelial carcinoma.

Dr. Hikmat Al-Ahmadie:

During cytology, you will be not able to say in situ or papillary because most of the times, that

designation requires more architectural assessment rather than individual cells, so I'm going to show

you example how the urothelial carcinoma cells in the urine may look like.

Yes, so this is a high magnification image from a urine cytology specimen taken from under the

microscope. These are the individuals, as these dark purple or blue structures in the middle of the

picture. These are the nucleus, the nuclei of tumor cells. You can see how they're different in size and

shape, different in the darkness quality just of the chromatin quality. They have indentations,

projections. These are all atypical features that do not resemble normal cells that we are very familiar in

how they look like, and with these type of features altogether, with the abundance of these cells in the

urine sample, we can comfortably say that this is cyg-diagnostic of a high grade urothelial carcinoma.

Dr. Hikmat Al-Ahmadie:

Urine cytology, as I said, it's a very simple process. It's a simple test. Doesn't require much. It's not

invasive. You don't stick a needle or anything, just a urine sample in the office. It's very sensitive for high

grade urothelial carcinoma. It's less sensitive for lower grade lesions, because again, you need to see

atypical features that are obvious here. In low grade lesions, you don't see the same features. And it's

also specific, which means if you don't see these atypical cells, you have a high confidence that you're

not seeing a high grade urothelial

carcinoma, and that's why you can say

it's very specific. If we go to the next

slide, just to show you where these

cells might come, this is a tissue

section. This is a biopsy. There's also

the biopsy processed in a similar way,

a little bit different because you have

to prepare, you have to fix the tissue

and cut the sections and make them

into a slide. As you can see at the top,

in both these images, all these dark

cells that have different sizes and

shapes, these are all malignant cells.

With this tissue section, I can easily

call it urothelial carcinoma in situ

because I have architecture. But as

you can see, the individual cells are

coming off of the main tissue

fragment and they'll be sloughed off

or shed into urine, and that's what will

make up the positive urine cytology.

I'll turn it back to you, Peter, I think,

for the next set of slides.

Dr. Peter Black:

Great. Yeah, I think from the

urologist's perspective, the urine

cytology is so important because we

often don't see carcinoma in situ.

That's something we'll come back to

while we're talking. This gentleman

had a CT scan. He had blood in his

urine, so that's part of the usual

workup, and everything was normal

with the kidneys and ureters.

Remember that carcinoma in situ and

indeed any cancer of the bladder, you

can get very similar lesions in the renal

pelvis and the ureters, and then upper

tracts. On cystoscopy, however, there

was a red patch on the back of the

bladder. It was a little bit raised. It

wasn't the typical sort of cauliflower

tumor that we often see, but it was

certainly suspicious, especially given

the positive cytology. So this gentleman we took to the operating room for a resection of this area that

you see in the micrograph here. Next slide please.

An important consideration, again,

this is particularly with carcinoma in

situ, is the use of enhanced

cystoscopy. There are two different

methods with which we can

enhance a cystoscopy. On the left-

hand side, you see the cysview,

which is the trade name. It's also

called blue light cystoscopy or

fluorescent cystoscopy. PDD is often

used in Europe as a terminology. It's

photo-dynamic diagnosis. But here,

you put a substance into the

bladder prior to the surgery, prior to

the TRBT, and it's taken up and

metabolized by cancer cells so that

these cells then fluoresce. When

you shine a blue light on it, a

fluorescent light, or, well, a blue

light, the cells will fluoresce and

they appear a bright pink. They

really stand out. We know that we can detect more tumors this way, and especially more carcinoma in

situ. Up to 40% more carcinoma in situ. It's particularly valuable, again, because we often overlook them

on regular white light cystoscopy.

Dr. Peter Black:

On the right-hand side, we have narrow band imaging, which is a little bit different. It uses filters to pull

out the blue and the green wavelengths that really accentuates blood vessels and changes in blood

vessel patterns. Vascularity will often accentuate tumors so that we can see them better. It's a little bit

easier to use because it's just a flip of a switch on the device and it doesn't require putting anything into

the bladder, but the evidence for its use is not as widespread. Next slide.

I just want to highlight some of the

differences in fluorescent cystoscopy.

And this is I think particular to the US

market actually, because it's not

necessarily available everywhere, but you

can actually do fluorescent cystoscopy at

the time of a surveillance cystoscopy in

the office. If a patient has had a prior

bladder cancer and they're undergoing

their routine cystoscopy, you can do

fluorescent cystoscopy that, for example,

is not available for us in Canada. Or, you

can do it, which is more common, more

universal, you do it at the time of a

broader tumor resection or biopsy, so if a patient has an identified tumor, you go to the operating room,

you give them the reagent beforehand and then you use it at the time of resection. So there are two

different uses, and I think as patients and caregivers, you need to be clear on the differences.

On the left-hand side, if you're talking about what we do at the time of surveillance cystoscopy, so it's

used to detect a recurrence. It's primarily patients with intermediate and high risk disease. So they

they've had tumors before. Based on the prior tumor characteristics, we know that they're high risk for

recurrence and we especially do it early on in their disease course. So if they had a tumor three months

ago and it's the first look, then that might be a time when we do it. We always have to consider the cost

and the treatment burden of all these tests. We can also do it, for example, if we see something on

white light that we're not, and white light's that the usual cystoscopy, if we're not quite sure what it is,

this might help us decide, yes, we need to biopsy that or no, we don't need to biopsy it. And overall,

there's especially one very good American trial that shows that it enhances the detection of high-grade

recurrence.

Dr. Peter Black:

On the right-hand side now, when we're using this at the time of resection, there's very good data from

multiple trials, North American and European trials that tell us that we'll detect more tumors, we'll

resect more thoroughly, patients will have a lower risk of recurrence, and that's a very important

endpoint. In particular for what we're talking about, we'll also find more carcinoma in situ. Next slide.

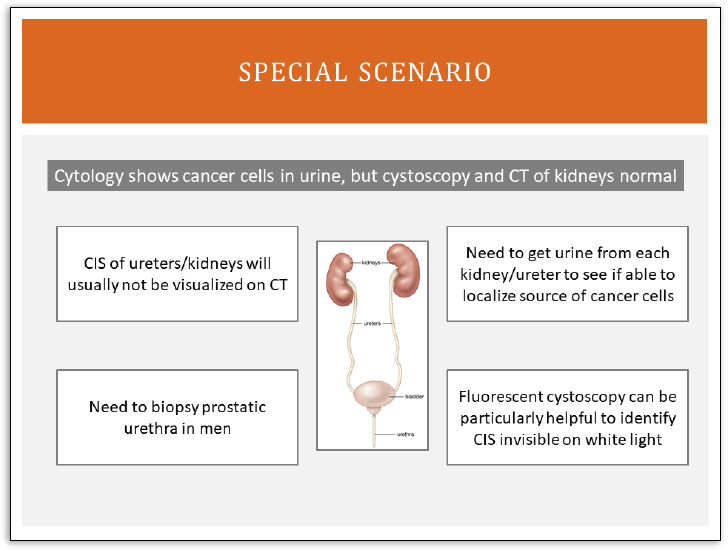

I wanted to highlight one

specific scenario that comes up

routinely and is particularly

relevant for carcinoma in situ. I

know there was already a

question in the chat or the Q&A

about carcinoma in situ of the

upper tracts. Upper tracts are

the ureters and the renal pelvis.

One scenario that we see

sometimes are patients who

come in to the office with a

urine cytology that clearly

shows abnormal cells, so it says

high-grade urothelial

carcinoma, so there are

malignant cells there, but we

don't see anything on

cystoscopy and we don't see

anything on a CT scan.

There, we have a specific

algorithm that we run through and we know, for example, that carcinoma in situ is something flat in the

ureter or renal pelvis is not going to be visualized on CT scan. We might not even see it, actually, when

we look at it with a camera. We can't do the fluorescent cystoscopy in the upper tract, so it can be

particularly tricky.

So what we do is we go to the operating room, we get urine from the right ureter and separately from

the left ureter so that if it is coming from one side or the other, we can determine that definitively. If we

find urine, let's say from the right renal pelvis, then the cytology is positive, but we don't see anything

with the camera and we don't see anything on CT scan, then we call that carcinoma in situ. We assume

there's carcinoma in situ there even though we don't see it.

Dr. Peter Black:

The other thing we do, then, so, if in a patient like this it's still more likely that it's actually from the

bladder and we're just not seeing it. So in the bladder, we will do the fluorescent cystoscopy and we'll

biopsy whatever we see there. And then in men, we always have to consider that it could be coming

from the prostatic urethra, where you can also get carcinoma in situ. It can be quite tricky. Upper tracts,

bladder, and prostatic urethra. Next slide.

So our patient, you'll recall he

had the positive cytology and

the red patch from the posterior

bladder wall. We took him to

the operating room for a

resection and we used the

fluorescent cystoscopy. It lit up

the patch that we saw, but it

also lit up a second patch bright

pink. And you can get an idea

from these pictures here, which

of course are not actually from

this patient. I stole these, but on

the left-hand side, the regular

white light, you don't really

appreciate much with even an

experienced eye, yet on the

right-hand side, it's really night

and day. It's very clear that

there's something there. So this

lesion was resected in addition

to the other one that we saw,

and the patient did well with the surgery, no complications. Next slide.

Dr. Peter Black:

So we sent the sample off to Dr. Al-Ahmadie, who's going to go through the pathology for us.

Dr. Hikmat Al-Ahmadie:

All right, so this is kind of a step-

wise process. Every sample that

is removed in the clinic or the

office goes to our pathology

department, and in the next few

slides, I'll just walk you through

some of the process and some of

the classification or how we

make the diagnosis, how we

look, how we evaluate these

specimens. And then at the end,

I'm going to show you a slide

that would represent that actual

biopsy from this gentleman.

Once we start the evaluation of

any bladder sample, in our mind

is when we find a malignant

process, where can we ask the

question, where can we fit it

from the current specification?

And as Dr. Black alluded to in the

beginning, you have non-invasive spectrum of tumors that are in the non-invasive category, and those

can be the carcinoma in situ, which is the subject of tonight's discussion, and then you can have papillary

lesions that can be low-grade and high-grade as opposed to the in situ, which is always a high-grade.

There are some rare benign tumors that we call them papillomas. They have distinct morphologic

features, and then the tumor starts invading. And then the tumor can invade into the lamina propria,

which is the most superficial layer of the bladder wall, or the one underneath the surface lining. And

then the deep invasive disease. This is our main challenges. Where can we fit this lesion that we identify

on these histologic sections in any of these categories? So if we go next slide.

Dr. Hikmat Al-Ahmadie:

This is one we come into. We identified a

malignant process. It's a urothelial

carcinoma now. Can we place it into in

situ flat disease or papillary? This is what

it is. You look at the image on the left,

this is the definition of urothelial

carcinoma in situ. We've identified these

cells that are very atypical. Again, the

features that we use are the variation in

the size and shape, the variation in the

coloring of these tumor cells, how they're

spaced. Are they overcrowded? Are they not respecting each other's borders?

Then, there are some other features that I may point to and I apologize if these may sound too

technical, but I'm happy to kind of discuss or answer any questions if you think and if it might need more

explanation. When the cells divide, they form a structure called mitosis, which is a sign of dividing in

cells and a growing tumor. You can see a lot of mitosis in these tumors as compared to the picture on

the right, which is the papillary tumors, which are basically a finger-like projections, and this is how the

tumor grows into the lumen of the bladder. It's simple recognition of the pattern that can tell you it's a

flat versus papillary disease, and these are all things that are [inaudible 00:23:04]. You can see it's be

definition high-grade disease, and it's a tumor that's just growing as if on the flat, the surface of the

bladder. Next slide.

Dr. Hikmat Al-Ahmadie:

Fortunately and unfortunately,

just to make things difficult and

challenging, urothelial carcinoma

in situ can come in different forms

and shapes. These are just

different examples. I just wanted

to show you, just to kind of put an

image to the name, so to speak.

We always rely on reference to the

normal urothelium, which is the

image on the top left. Here you

can see it doesn't take much, you

can see, comparing this image to

all the other five images. You

could see how we use the

reference normal urothelium to

help us identify abnormal lesions.

Normal urothelium is very orderly

structure, multiple layers of

different types of cells start from

the base all the way to the top. All

of these cells are important. They

have normal functions in the bladder. For example, this middle layer can be four, five cells thick, but it

can become two cells thick if the bladder is distended and becomes flattened.

All the other images on the right and the bottom, these are different shapes of urothelial carcinoma in

situ. Again, highlighting the features that we rely on and we use: the variation in the size and shape, the

discoloration, the growth pattern. Some of these patterns can be deceptive, like the one on the top left.

These large cells are individual tumor cells just growing along the normal urothelium. We use the term

spread, but this could be challenging and this could be one of these examples where not many tumor

cells go into the urine, for example, because these cells are just growing under normal urothelium,

compared to the picture in the middle and the bottom. This is when you have a lot of dis-cohesive,

disjointed tumor cells that can easily shed into the urine.

Dr. Hikmat Al-Ahmadie:

The last image on the bottom right, this is a tumor, carcinoma in situ, that is involving some normal

invaginations in the bladder. Sometimes all the surface urothelium is normal. You don't see any

malignant cells, but you could see these tumor cells inside this invagination. Sometimes that can make it

more difficult to treat. If we go next slide.

As much as we want to believe or

we want to think of urothelial

carcinoma in situ as distinct from

papillary tumors, a lot of times

they coexist or they overlap,

coexist or they develop after one

another. These are some terms

that we use, primary urothelial

carcinoma in situ or primary CIS is

one. On the first presentation, it is

urothelial carcinoma in situ with

no associated papillary tumor, or

you can have secondary CIS,

where there is urothelial

carcinoma in situ developing

concomitantly with or after a

prior diagnosis of a papillary

urothelial carcinoma. Of course

there's always attempt to try to

link this to differences in outcome

or responses to types of therapy

even though it's not necessarily conclusive yet, but it seems that some people believe that primarily

urothelial carcinoma in situ may be associated with a worse response to rate to these conservative

treatments. Next slide.

This is one example I wanted to show

you, is as I said, as much as we like to

keep them separate and unique,

sometimes they coexist. This is one

example here. This is the same TUR

specimen from the same individual.

You can see them grouped together,

coming together within the same

container from the same patient. If

you look at the higher magnification

picture on the right top, this is a

papillary tumor. You can see these

finger-like projections sticking into

the bladder wall, out the bladder

lumen, versus the picture on the

bottom, the growth is very flat, just

along the surface urothelium. That's

the distinct growth pattern for

urothelial carcinoma in situ. So a

papillary tumor and a flat disease can coexist within the same specimen. Next.

Dr. Hikmat Al-Ahmadie:

And of course another important

thing, when we assess, when we

evaluate the urothelium here,

and every time we see urothelial

carcinoma in situ, the next most

important thing is to determine

whether there is any amount of

invasive disease or whether this

tumor is purely non-invasive

urothelial carcinoma in situ. We

look carefully at the base of the

surface urothelium and we are

carefully evaluating the stroma

underneath it, these layer that

are loose underneath it. When

we start seeing these individual

cells that are highlighted by these

green arrows or arrow hats,

that's when we start calling this

invasive disease. Depending on

the level of invasion and the

amount of the invasive disease,

we can call it focal superficial, and if it goes deeper than the first layer... if it remains in the first layer,

you call it laminal invasion or T1 disease, as you might hear about it. And if it goes further deep into the

bladder wall, it may invade the muscular layer, where you call it muscle-invasive bladder cancer. These

features are not depicted here on the slide, though. Okay, next. I think we went back, so... Yes, next

slide.

Yeah, and so this is another example

that Dr. Black alluded to that could

present challenges in evaluating

urothelial carcinoma in situ. This is a

tumor that is involving... here, what we

see in the picture is involvement of

prostatic ducts, which are immediately

underneath the urethra. This is a tumor

that kept kind of crawling along the

surface urothelium, involving the

urethra and went all the way into the

prostatic ducts. It's not invasive, it just

keeps colonizing all these ducts and

makes it difficult to detect sometimes,

difficult to remove and difficult to treat

overall. Next.

This is going back now to the actual case

here in this presentation. This is the biopsy

from the gentleman, and as you can see,

after I showed you all the slides, now

everyone should be able to recognize that

yes, these cells are very atypical. They're

different sizes and shapes, different colors.

They don't respect each other's borders.

There are a lot of variations amongst them.

This is diagnostic of urothelial carcinoma in

situ. Next. Yeah, that's yours. Back to you.