University of Tennessee at Chattanooga University of Tennessee at Chattanooga

UTC Scholar UTC Scholar

Honors Theses

Student Research, Creative Works, and

Publications

5-2023

Creator as audience: mixtape albums as an expression of life and Creator as audience: mixtape albums as an expression of life and

memory memory

Sadie Montague

University of Tennessee at Chattanooga

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.utc.edu/honors-theses

Part of the Graphic Design Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Montague, Sadie, "Creator as audience: mixtape albums as an expression of life and memory" (2023).

Honors Theses.

This Theses is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research, Creative Works, and Publications

at UTC Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UTC Scholar.

For more information, please contact [email protected].

Creator as Audience:

Mixtape Albums as an Expression of Life and Memory

Sadie LaVaun Montague

Departmental Honors Thesis

University of Tennessee at Chattanooga

Graphic Design

Examination Date: April 10, 2023

Matt Greenwell Ron Buffington

UC Foundation Professor UC Foundation Professor

Graphic Design Painting and Drawing

Jonathan McNair

UC Foundation Professor

Music Theory and Composition

1

Table of Contents

Research Paper

Bibliography

Project Documentation

Artist Statement

2

13

15

26

2

Research Paper

A universal part of the human condition is the desire to orient ourselves in a complex world. Life is

imbued with a longing to find a strong sense of self, purpose, and belonging, and to understand

how we relate to one another as a community. Visual art and music have unique ways of exploring

these questions by capturing the complexity of the human experience and informing both cultural

and personal identity. My thesis project explores how the combination of music and design can

engage with people’s personal stories through the lens of our experiences within popular culture.

My desire to discover the emotive potential of music and design together is a part of a

larger historical thread of inquiry. A notable example is the work of composer Claude Debussy. As

Impressionist painters were disrupting conventional approaches to visual representation at the turn

of the 19

th

century, Debussy implemented alternative strategies in music as well. Inspired by

Impressionist painters’ abstract, interpretive impulses and common themes of Impressionism, like

the effects of sunlight on landscapes and structures, Debussy introduced “blurred and seemingly

indistinct musical structures” in his compositions.

1

In his composition Nocturnes, he attempts to

capture specific visual experiences within the mood of the music. This connection between music

and visual image is overt in his names for the three movements: “Clouds,” “Festivals,” and

“Sirens.”

2

In the 1930s, Stuart Davis’s colorful, rhythmic paintings draw directly from the exuberance

of American Jazz.

3

Later in the 20

th

century, experimental musician John Cage and painter Robert

Rauschenberg shared a unique creative relationship through their interest in collage processes in

their respective media. Cage expanded the boundaries of music by using clips of sound from

everyday life – the clanking of pots and pans, cars on the street, bodily noises, etc. – to create

unconventional compositions. These distinctive pieces broadened audiences’ understanding of

the potential of music as Cage considers how the everyday can be raw material for creativity and

1

Leach, Brenda Lynne. “Looking and Listening: Conversations Between Modern Art and Music.”

Lanham, Maryland:

Rowman & Littlefield,

(2015): 107-118.

2

Leach, “Looking and Listening,” 117.

3

Leach, “Looking and Listening,” 17-26.

3

play. Similarly, Rauschenberg collaged elements of everyday life into his work by incorporating

found scrap materials into the surface of his paintings. Like Cage, Rauschenberg disrupted the

conventions of his medium. While Cage and Rauschenberg worked in entirely different artistic

fields, they inspired each other and shared similar conceptual goals as they leveraged collage

operations to enrich viewers’ conceptions of art and life. Another prominent music-art collaborative

pair is painter Mark Rothko and composer Morton Feldman, who inspired each other in their

modernist pursuit of pure form (pure sound, in Feldman’s work) and atmospheric contemplation.

The list goes on. Clearly, artists and musicians have been considering the generative potential of

the convergence of music and art for a long time. This creative history provides context for my

research as I investigate intersections of music and design in contemporary popular culture.

In the first decades of the 20

th

century, the phonograph made the recording and mass-

distribution of music possible. For the first time, music-listening experiences were no longer bound

to live, public performance. By the 1930s, when the long-play record was released, families could

purchase albums and listen to 30 minutes of music on demand – a completely new, liberating

experience.

4

For the first time, music could be collectively understood and socially shared by a

general public separated in time and space. Arguably, this was the birth of popular music culture.

During this cultural shift, recorded songs were a novelty, and it was a wonder that music could be

freed from limitations of proximity and time, allowing it to be preserved for succeeding generations

of listeners.

5

This new culture surrounding music distribution quickly expanded and intermingled

with the popular culture of graphic design.

Before the 1940s, vinyl records were encased in simple, brown paper sleeves, for

protection. Alex Steinweiss, an illustrator who worked for Columbia Records during this time,

revolutionized this generic packaging standard by conceiving of the album cover as an extension

of the music in visual form. Steinweiss’ exuberant, colorful designs encased albums of

4

Millard, Andre. “A Phonograph in Every Home.”

In

America on Record: A History of Recorded Sound

, (2005): 2nd

ed., 37–64. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/CBO9780511800566.006.

5

Millard, “Phonograph,” 61.

4

accomplished jazz musicians and renowned classical composers, giving them new visual context.

He introduced the now-conventional view that music and art could and should live harmoniously

alongside each other. His designs marked the beginning of a contemporary music tradition that

thrives on visual identity as an integral part of the listening experience.

6

Over the course of the 20

th

century, record sleeve designs became an increasingly

complex, delightful unraveling experience. Special edition LPs of the 60s, 70s, and 80s are prized

for the artful arrangement of photographic and illustrative designs on the outside cover, which

continue onto the inside surface and onto folds and pockets, where a poster or set of poster lies,

waiting to be discovered. By the time a listener reaches the record, they have already

encountered a thematically cohesive series of designed surfaces, like a carpet rolled out to

introduce the final musical experience. This tactile, visual unraveling is incredibly different from our

mode of consuming music today. In a time when music is available instantaneously through the

internet, the musical experience has been largely stripped of its physicality. Interestingly, our

culture has responded to the sensory spareness of digital consumption with a renewed fondness

for the artistic tradition of the vinyl record and a nostalgia for the tactility that is lost with digital

music consumption. In the past two decades, we have seen a cultural return to physicality and a

renewed love for analog music formats as collectible items as the digital age has recontextualized

the vinyl record and given it new culturally iconic meaning. Vinyl has become a material signifier of

a warm, intimate listening experience.

7

This return to physicality suggests a fascination with the

past and with seemingly more “authentic” experiences. Considering that for millennia human

beings have experienced the world though all sensory modalities, digitization is a jarring shift,

resulting in a yearning for past physical connections and the desire to renew our emotional

relationships with objects – in this case, analog music objects.

8

Jacques Derrida’s theories on

6

Jackson, Ashawnta. “Album Cover Artwork Was Super Boring before Alex Steinweiss,”

JSTOR Daily,

May 2021.

https://daily.jstor.org/album-cover-artwork-was-super-boring-before-alex-steinweiss/.

7

Bartmanski, D., & Woodward, I. “The Vinyl: The Analogue Medium in the Age of Digital Reproduction.”

Journal of

Consumer Culture

, (2015): 15(1), 3–27. https://doi-org.proxy.lib.utc.edu/10.1177/1469540513488403

8

Xue, Haian and Martin Woolley. “Creatively Designing with/for Cultural Nostalgia: Designer’s Reflections on

Technological Change and Loss of Physicality.”

IASDR

(2013).

https://www.ibdsite.com/iasdr-2013-aug-26-30-2013/.

5

hauntology address our culture’s relationship with the past and offers a compelling perspective on

our connection to objects, especially in our society’s transition from analog to the digital. Simply

stated, hauntology calls attention to the preeminence of the cultural past within contemporary

objects and media as an invisible force, like a ghost or a trace.

9

Through this lens, the physicality of

the past “haunts” us as we may feel drawn to obsolete technology and continue to perpetuate its

use, even when it is not practical to do so. Thus, the emotional and cultural allure of the vinyl

record that is often difficult to explain or understand is an indication of the persistence of the past

within our contemporary lives. This yearning for the past is an important element of my project. As I

consider how a curated audio-visual experience can have unique emotional potency for viewers, I

am drawing from the vinyl record packaging experience to evoke feelings of personal memory,

cultural nostalgia, and tactile satisfaction.

As I tap into personal and cultural memory in my project, I am considering what it means to

design with a consciousness about how human beings relate to the past. Within psychological and

historical scholarship on the topic, nostalgia is often discussed in terms of its negative implications.

A driving force of nostalgia is the desire to return to or recreate the past – real or imagined.

Psychologically, this longing to return to the past hinges on discontentment with the present or a

sense of lack and loss, hence nostalgia’s common association with pain and denial. Through a

broader historical lens, nostalgia is often regarded as a dangerous fantasy that can result in

collective ignorance and “social amnesia.”

10

Characterized as “restorative nostalgia” by Russian-

American scholar and artist Svetlana Boym, this impulse to return to or recreate an idealized

homeland or time can give way to strong ideological and revolutionary sentiments often mediated

by emotion and myth rather than by logic or knowledge.

11

In the sense that nostalgia can be a form

of individual and societal escapism, its negative implications are understandable. However, there

9

Rahimi, Sadeq.

The Hauntology of Everyday Life

.

Cham, Switzerland: Springer

(2021): 1-8.

10

Pickering, Michael, and Emily Keightley. “The Modalities of Nostalgia.”

Current Sociology

54, no. 6 (2006): 919–941

11

Boym, Svetlana. "Nostalgia and its Discontents."

The Hedgehog Review

9, no. 2 (2007). https://link-gale-

com.proxy.lib.utc.edu/apps/doc/A168775861/AONE?u=tel_a_utc&sid =bookmark-AONE&xid=fe65cf5e.

6

are also plausible arguments for nostalgia’s benefits. According to Boym, “reflective nostalgia,” as

opposed to restorative nostalgia, does not attempt to change the present. With this type of

longing, there is no specific loss or homeland to recreate. Rather, it engages in a more general

reminiscing with acceptance that the past is not attainable. Reflective nostalgia is an untargeted

and ambivalent rumination, potentially “ironic and humorous,” and is fully aware of its engagement

in memory and fantasy.

12

In the context of my project, reflective nostalgia is integral to how we

culturally and individually connect with music over time. Cultural identification with specific music

genres and styles, the celebration of legendary and historic celebrity musicians, and emotional

attachment to past music formats, like the vinyl record, are arguably the result of a collective

recollection of, and fondness for, the past. Popular music culture keeps past traditions relevant,

while integrating them into new artistic and cultural production. Because reflective nostalgia is

longing for a generalized, rather than specific, past, individuals who are too young to have used

vinyl records or to have experienced analog music memorabilia may still feel nostalgic and

sentimental at the sound of the crackling record or at the sight of a cassette tape. With this in mind,

the analog is emotionally accessible to people of a variety of ages and walks of life. Some scholars

note that collective feelings of nostalgia and reminiscence could be a unifying experience as

society attempts to acclimate to a rapidly changing modern environment. Especially in our

increasingly dematerialized, digital age, nostalgia could have democratic value as we navigate

new technologies, new ways of communicating, and new forms of cultural transmission.

13

Even

while Boym expresses ardent criticisms of cultural nostalgia, she admits that “the universality of

longing can make us more empathetic toward fellow humans.”

14

This potential for a heightened

sense of empathy and social unity stirred by nostalgic feelings is central to my project’s

interpersonal goals. Through a careful consideration of how now-obsolete music objects may

12

Boym, “Nostalgia,” 15.

13

Pickering, “The Modalities of Nostalgia,” 923.

14

Boym, "Nostalgia,” 9.

7

trigger nostalgia in an audience, I hope to provoke thoughtful, sentimental reflection – a

conversation in which everyone can participate.

While the vinyl record represents a unique nostalgic iconicity among music lovers, the

cassette tape holds a different kind of cultural weight. While vinyl albums are iconic because of

their artistic and material legacy, the cassette tape provides unparalleled creative power for the

everyday listener because of the ability to record personal audio onto blank tapes. During the

height of their popularity, the mixtape was the ultimate do-it-yourself music distribution method. An

individual could curate and compile songs of any genre at their own discretion. This music collage

process subverted industry-standard recording and offered a new, highly personalized method of

cultural consumption, creation, and distribution.

15

To grasp the cultural weight of the mixtaping

tradition, it is important to understand its relationship to the role of collage in art subculture.

Conventionally, collage is the process of cutting fragments of visual material from photographs,

books, newspapers, posters, magazines, etc., removing them from their original contexts, and

pasting them together into a new form. Since collage involves the rearranging of existing material

rather than creating something entirely new, collage is often regarded as casual, accessible, and

anecdotal. In the words of artist and theorist Richard Flood, “Anyone can make [collage], and most

do.”

16

With its disjointed, fracturing process, collage is an art of conglomeration and juxtaposition.

Since images that normally would not meet within their real-world contexts are arranged side by

side, things that were conventionally recognizable before are now introduced to us in a new,

surprising, and potentially disruptive way. This process of fracture and reunification “makes us

rethink the significance of those familiar images altogether.”

17

Thus, collage is not merely a visual

style but an exploratory artistic process that inspires an alternate way of thinking. This

15

Glennon, Mike. "Consumer, Producer, Creator: The Mixtape as Creative Form."

Organised Sound,

24, no. 2 (2019):

164-173. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355771819000207.

16

Flood, Richard, Hoptman, Laura J., Gioni, Massimiliano, and New Museum of Contemporary Art. “Collage: The

Unmonumental Picture.” New York, N.Y.:

Milano: New Museum; Electa

, 8-15 (2007).

17

Flood, “Collage,” 10.

8

recontextualization is inherent to the medium. The mixtape, then, as a result of a collage process,

gives mass-distributed songs new meaning apart from their traditional delivery within an album, as

a part of a movie soundtrack, or on a programmed radio station. My work takes this

recontextualization a step further as I create thematic mixtapes through a crowd-sourced survey

process. Each mixtape is comprised of one song from each individual contributor, and the

mixtapes feature diverse styles, genres, and musical eras that might never be juxtaposed

deliberately within a “normal,” everyday listening experience. As one would imagine, considering

the individuality of musical taste, the songs on each mixtape are in dialogue with each other in

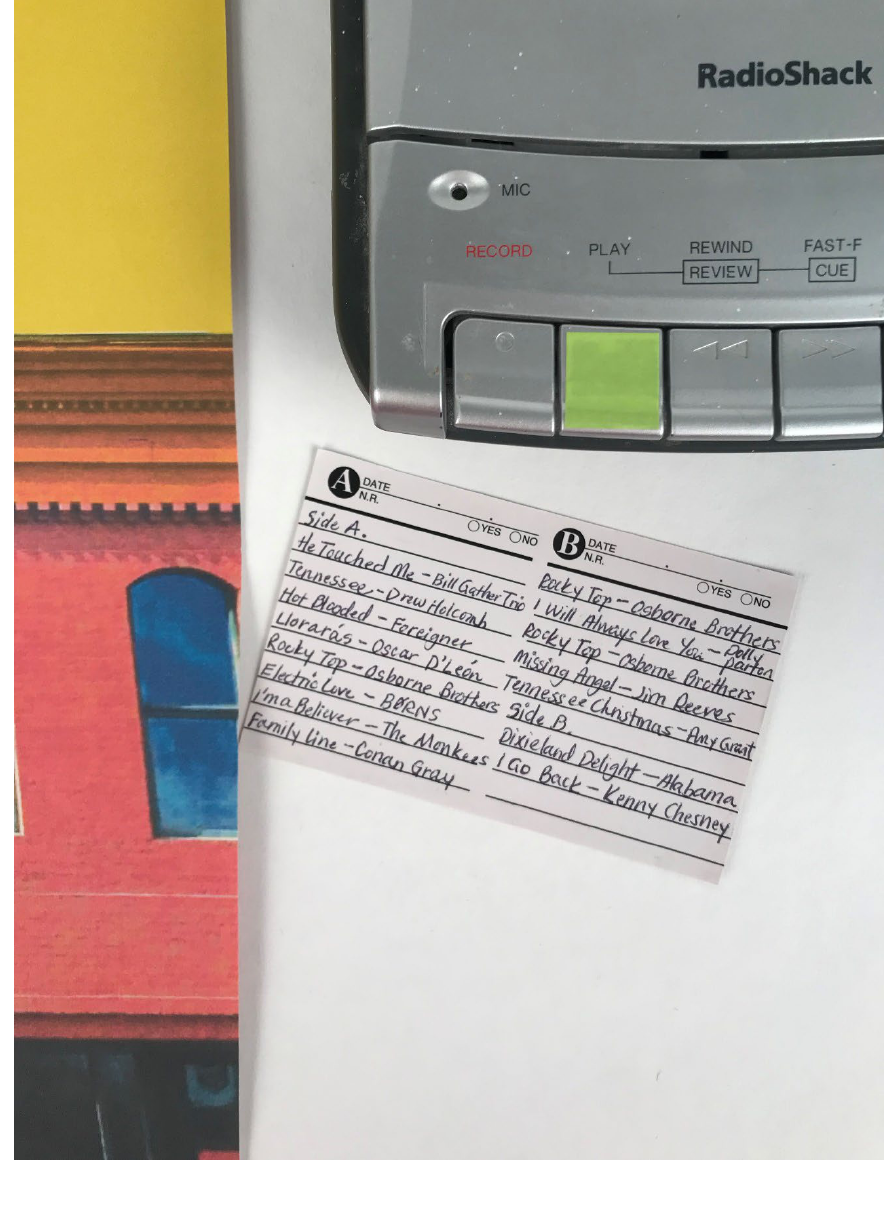

surprising ways. For example, on the mixtape “It Feels Good to be Home,” the traditional hymn “He

Touched Me,” followed two tracks later by Foreigner’s “Hot Blooded,” juxtaposed with the iconic

bluegrass anthem, “Rocky Top,” is a bewildering stylistic whiplash. These songs are compiled

alongside others ranging from contemporary pop, to folk and country, to Christmas songs, making

for an eclectic playlist. This disorientation is simultaneously clarified and complicated by the

mixtape’s title. “It Feels Good to be Home” signifies that the songs are not curated conventionally,

by mood or genre, but by one unifying factor: the notion of home. However, this theme/category

also complicates our perception of the songs as we try to understand them as an expression of

origin and belonging beyond our traditional cultural associations with them. Memory and life

experience is superimposed onto these songs, morphing them in our imagination through their

combination. The collage aspect of mixtapes’ creation, magnified by an unconventional, collectivist

song-selection process, causes listeners to make new conceptual connections as we hear the

songs both in relation to each other and in relation to the theme established by the mixtape’s title.

My use of the mixtape to map the memories and feelings of people results in a sometimes

confounding yet surprisingly coherent listening experience – one that makes us rethink what it

may mean to experience life as a part of a collective memory or story.

In addition to the power of the mixtape as collage, its place within interpersonal exchange

makes it a uniquely intimate medium. Mixtapes were one-off collections made to be distributed –

9

gifted to friends, family, or high school crushes. While the individualized collage ethos of mixtaping

lives on in the digital playlist of today, the time and labor of compiling songs and recording a

mixtape for a friend is a familiar experience for people who grew up in the 1970s, ‘80s, and ‘90s,

18

imbuing cassette tapes with the nostalgia and cultural memory that aligns with my project’s

personal, emotional goals. The cassette tape is not only nostalgic because it is an obsolete, analog

music technology, but also because it represents a slower and more intentional social culture, one

in which gift giving is deliberate – requiring diligence, creativity, and a close relationship with the

receiver. Artist and scholar Clive Dilnot discusses the social experience of gift giving and its

implications for human culture and relationships. Dilnot first draws attention to common social

anxieties of gift-giving. Giving a gift may often feel obligatory within formal, institutionalized

contexts like Christmas, bridal showers, or birthdays. In these cases, the giver likely does not know

what the recipient wants and so feels stressed and resentful of the obligatory social gesture.

19

Thus, the concept of the gift as a joyful personal act becomes a mere transactional commodity.

The “gift-article,” as Theodor Adorno defines it, is an ostentatious object that acts as a naïve stand-

in for a sincere gift. These objects function under the guise of sentimentality, but represent only

the emptiness of material obligation. Because these gift-articles are usually mass-produced and

not specific to the receiver, a “generalized culture of gift-articles” marks the death of the true gift.

20

While this phenomenon may be an accepted truth of our hurried modern age, its implications

should not be understated. Fundamentally, this ubiquitous yet often unspoken experience is

symptomatic of a lack of authentic relationships with one another. As Dilnot suggests, we have

forgotten how to give joyfully and genuinely because we have forgotten how to have intimate

relationships. We have forgotten that “the act of giving … [is integral to] the art of being human.”

21

Within this social context, a true gift – one that requires forethought, generosity, and creativity –

18

Glennon, “Consumer,” 172.

19

Dilnot, Clive. “The Gift.”

Design Issues

9, no. 2 (1993): 51–63.

20

Dilnot, “The Gift,” 53.

21

Dilnot, “The Gift,” 54.

10

means more than ever before. The mixtape could be understood as the quintessential gift. Having

an intimate knowledge of the music tastes and interests of a friend or loved one, collecting and

curating a list of songs the giver wants to share, and taking the time and labor to carefully record

them onto a tape – these are acts of intentionality and dedication almost alien to today’s fast-

paced prefabricated culture. This aspect of the mixtape, that it is a personal, individualized gift,

inspires me to use it as the medium to express relatable life themes and individuals’ personal

stories. As a cultural symbol of friendship, community, and generosity, the mixtape is a strategic

design choice in my work. As a gift, the mixtape allows for the content of my project to have a

unique emotional weight. Its intimate connotations will communicate to viewers/listeners that the

contents of the mixtape albums I am creating are sincere, one-of-a-kind, and intended specifically

for them.

The affective responses I want to evoke through my work are not achieved by these music

formats and their design histories alone. The cultural significance of music itself is at the heart of

my research. Music’s emotive power and nostalgic qualities are the conceptual drive, the vehicle

through which I will be able to engage with viewers and listeners on a personal level. Scholarship

on music’s role in memory generally agrees that nostalgic qualities are inherent to music more

notably than other artistic media. Music’s ability to conjure moving surges of memory make it a

powerful tool for recollecting potent moods and feelings from the past.

22

This is why music is

considered a useful memory-retrieval tool for people suffering from dementia, and music’s unique

role in our long-term memory and identity formation makes it a psychologically influential

medium.

23

From a neurocognitive standpoint, our brains cling to music and sound in order to form

autobiographical memory and internal narratives that construct our sense of self.

24

This lens also

extends to the formation of collective identity and the need to understand our role within social

22

Pickering, Michael, and Emily Keightley. “The Modalities of Nostalgia.”

Current Sociology

54, no. 6 (2006): 919–941

23

Baird, Amee and William Thompson. “The Impact of Music on the Self in Dementia.”

Journal of Alzheimer's Disease.

(2018): 61. 827-841. 10.3233/JAD-170737.

24

José van Dijck, “Record and Hold: Popular Music Between Personal and Collective Memory,” Critical Studies in

Media Communication, (2006): 23:5, 357-374, DOI: 10.1080/07393180601046121

11

groups.

25

These psychological mechanisms enable specific songs to take on personal meaning to

individuals, while also serving as a source of societal belonging. Certain artists or genres may be

important in the formation of cultural heritage and generational identity,

26

such as bluegrass’

importance to Appalachian history and culture or the identification with rock bands like Aerosmith

and Journey for American concert-goers in the 1970s and ‘80s. These strong cultural ties to

genres, songs, and artists play into music’s nostalgic potential and its ability to evoke melancholic

longing for the past.

27

Clearly, music informs our personal and social identity, our memory, and our

cultural heritage. Because of these special qualities, it is a powerful force to provoke

contemplation and reflection and to stir poignant emotions like joy, sadness, longing, excitement,

grief, awe, and hope.

At the same time, our experiences of songs in popular culture have always been deeply

entrenched in the designs that contain them. The auditory encounter is only one element of the

musical experience, since design is usually the first point of contact that a listener may have with a

body of music. Hence, the design of an album’s cover serves as an index for what is on the inside.

This idea of the design as a package is central to Roland Barthes’ theories on iconography’s role in

culture. In his book Empire of Signs, Barthes suggests that a designed container, like a wrapped

box or a decorated envelope, has two competing effects: it both conceals what is on the inside

and simultaneously discloses the value of its contents, giving viewers a point of entry through

which to make judgements about the object inside. Thus, the visual nature of an object’s

encasement may become more culturally important than the object itself.

28

Philosopher Maurizio

Vitta also asserts the dominance of the value-image in society, differentiating between an object’s

use-value and its cultural image. He asserts that design is a “simulacrum,” an instrument of social

25

van Dijck, “Record.”

26

Bennet, Andy and Susanne Janssen. “Popular Music, Cultural Memory, and Heritage,”

Popular Music and Society,

(2016): 39:1, 1-7, DOI: 10.1080/03007766.2015.1061332

27

Pickering and Keightley, “The Modalities of Nostalgia,” 936.

28

Barthes, Roland, and Richard Howard. “Packages” in

Empire of Signs

. Translated by Richard Howard. First

American edition. New York: Hill and Wang, a division of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, (1982).

12

analysis that informs and affirms a society’s values.

29

By this argument, a society’s attachment to an

object or product is, in reality, a fascination with its image, leaving the object mobile and empty, a

vessel of value in a society’s imagination.

30

By Barthe’s and Vitta’s premise, the mixtapes in my

project would be considered the “empty object” encased within the albums (packages

communicating sign-values). These theories productively complicate the musical encounter that

remains at the heart of my project, but affirm my motivations for packaging the music playlists with

a deliberate design sensibility. I am leveraging the cultural supremacy of images to communicate

with viewers in a very immediate and visceral way. The vinyl-inspired construction of the album

packages, the images and poster designs that are within them, and the cassette tape as a

nostalgic vehicle for the delivery of the music, all have powerful cultural and emotional

connotations. Thus, my design choices are not merely supporting elements of my project but are

crucial to its effectiveness in evoking emotional, nostalgic responses and provide emotional and

cultural context for the musical compilations.

Ultimately, where design and music meet in popular culture is where we form our core

experiences and memories, participating in a complex cultural amalgamation. Fusing design and

music, while making use of each medium’s unique strengths, allows me to create an experience

that is emotionally poignant and thought-provoking, encouraging viewers/listeners to contemplate

their participation in life around them.

29

Vitta, Maurizio, and Juliette Nelles. “The Meaning of Design.”

Design Issues 2

, no. 2 (1985): 3–8.

30

Barthes, “Packages,” 47.

13

Bibliography

Barthes, Roland, and Richard Howard. “Packages” in Empire of Signs. Translated by Richard

Howard. First American edition. New York: Hill and Wang, a division of Farrar, Straus and

Giroux, 1982.

Bartmanski Dominik and Ian Woodward. “The Vinyl: The Analogue Medium in the Age of Digital

Reproduction.” Journal of Consumer Culture, (2015): 15(1), 3–27

Bennett, Andy and Susanne Janssen. “Popular Music, Cultural Memory, and Heritage” Popular

Music and Society, 39:1, 1-7 (2016), DOI: 10.1080/03007766.2015.1061332.

Boym, Svetlana. "Nostalgia and its Discontents." The Hedgehog Review 9, no. 2 (2007).

https://link-gale-com.proxy.lib.utc.edu/apps/doc/A168775861/AONE?u=tel_a_utc&sid

=bookmark-AONE&xid=fe65cf5e.

Cage, John. "Experimental Music." Silence: Lectures and writings, 7 (1961).

Caivano, J.L. “Color and Sound: Physical and Psychophysical Relations.” Color Research &

Application, 19: 126-133 (1994). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1520-6378.1994.tb00072.x

Dilnot, Clive. “The Gift.” Design Issues 9, no. 2 (1993): 51–63.

Dunsby, Jonathan. “Considerations of Texture.” Music & Letters, 70, no. 1 (1989): 46–57.

http://www.jstor.org/stable/735640.

Fisher, Mark. “What Is Hauntology?” Film Quarterly, Vol. 66, no. 1 (2012): 16–24. https://doi-

org.proxy.lib.utc.edu/10.1525/fq.2012.66.1.16.

Flood, Richard, Hoptman, Laura J., Gioni, Massimiliano, and New Museum of Contemporary Art.

“Collage: The Unmonumental Picture.” New York, N.Y.: Milano: New Museum; Electa, 8-15

(2007).

Freedberg, David, and Vittorio Gallese. “Motion, Emotion and Empathy in Esthetic Experience.”

Trends in Cognitive Sciences 11, no. 5 (2007): 197–203.

Glennon, Mike. "Consumer, Producer, Creator: The Mixtape as Creative Form." Organised

Sound, 24, no. 2 (2019): 164-173. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355771819000207.

Ione Amy and Tyler Christopher. "Was Kandinsky a Synesthete?" Journal of the History of the

Neurosciences 12, no. 2 (2003): 223-226.

Juslin, Patrik N., and Daniel Västfjäll. "Emotional Responses to Music: The Need to Consider

Underlying Mechanisms." Behavioral and Brain Sciences 31, no. 5 (2008): 559-75.

doi:10.1017/S0140525X08005293.

14

Leach, Brenda Lynne. “Looking and Listening: Conversations Between Modern Art and Music.”

Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015.

Long, Paul, and Simon Barber. “Voicing Passion: The Emotional Economy of Songwriting.”

European Journal of Cultural Studies 18, no. 2 (April 2015): 142–57.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549414563298.

Vitta, Maurizio, and Juliette Nelles. “The Meaning of Design.” Design Issues 2, no. 2 (1985): 3–8.

Mitchell, Brenda Marie. "Music That Makes Holes in the Sky": Georgia O'Keefe's Visionary

Romanticism.” University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1996.

Palmer, Stephen E, Karen B Schloss, Zoe Xu, and Lilia R Prado-Leon. “Music–Color Associations

Are Mediated by Emotion.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences - PNAS 110,

no. 22 (2013): 8836–8841.

Rahimi, Sadeq. The Hauntology of Everyday Life. Cham, Switzerland: Springer (2021): 1-8.

Russolo, Luigi. "The Art of Noises: Futurist manifesto." Audio Culture: Readings in Modern

Music (2004): 10-14.

Vernallis, Carol. “Beyoncé’s Overwhelming Opus; or, the Past and Future of Music Video.” Film

Criticism 41, no. 1 (2017).

Webster, G.D., Weir, C.G. “Emotional Responses to Music: Interactive Effects of Mode, Texture,

and Tempo.” Motivation and Emotion, 29, 19-39 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-

005-4414-0.

Xue, Haian and Martin Woolley. “Creatively Designing with/for Cultural Nostalgia: Designer’s

Reflections on Technological Change and Loss of Physicality.” IASDR (2013).

https://www.ibdsite.com/iasdr-2013-aug-26-30-2013/.

15

Project Documentation

Lifetimes

, 2023

handmade cassette tape albums, 8 x 8 inches:

foam core board, mounting board, and recycled paper

bound with cotton cloth tape

music audio on cassette mixtapes: 7 hours, 54 minutes, and 8 seconds

posters, 14 x 14 in

Courtesy and copyright the artist

Songs, photos, and personal testimonies provided by anonymous contributors.

Visit this link to listen to the digital version of the mixtape album audio:

https://open.spotify.com/collection/playlists

Lifetimes

multimedia installation, handcrafted mixtape albums, 8x8in, print and audio, 2023

16

detail of

Lifetimes

installation, handcrafted mixtape albums, 8x8in, print and audio, 2023

17

detail of

Lifetimes

installation, handcrafted mixtape albums, 8x8in, print and audio, 2023

18

detail of

On the Road

, handcrafted mixtape album, 8x8in, print and audio, 2023

19

detail shot from

The Good Ole Days

, handcrafted mixtape album, 8x8in, print and audio, 2023

20

It Feels Good to be Home

, handcrafted mixtape album, 8x8in, print and audio, 2023

21

For My Love

, handcrafted mixtape album, 8x8in, print and audio, 2023

22

detail of poster and inside cover from

For Hard Times

, handcrafted mixtape album, 8x8in, print and audio, 2023

23

detail of song list from

It Feels Good to be Home

, handcrafted mixtape album, 8x8in, print and audio, 2023

24

detail of poster and cassette player from

Let’s Dance!,

handcrafted mixtape album, 8x8in, print and audio, 2023

25

detail of

Thinking of You

, handcrafted mixtape album, 8x8in, print and audio, 2023

26

Artist Statement

My background as a songwriter and musician is the foundation of my graphic design work. In fact, I

often see the two as inseparable. The art of narrative and storytelling, the emotion of music and

lyrics, and the community of sharing songs with others has developed in me a creative impulse

toward empathy. Simply put, my work explores life. I believe we all need more transparency and

sincerity as we try to orient ourselves within a complex world. So, my art is a framework for

dialogue about our collective human experience, including our search for connection, purpose,

and belonging.

As my work communicates these relatable themes and narratives, my creative process lends itself

to the casual, the personal, and the handmade. Analogue processes, such as handwritten text and

lettering, inspiration from everyday conversations, and personal photographs from my friends and

family, imbue my work with intimacy and openness. Ultimately, I use collage as a powerful,

emotional tool. Collage – the process of cutting and pasting elements from different sources

together to form a new whole – is there a better analogy for life? Life is an amalgamation; yet, in its

scattered complexity is the opportunity for beauty and wholeness.