Current Musicology 107 (Fall 2020)

©2020 Duinker. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons-Attribution-

NonCommercial-NoDerivatives License (CC BY-NC-ND).

93

Ben Duinker

Introduction

Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson—record producer, drummer for The Roots, and

bandleader for The Tonight Show—remembers exactly where he was the day

“Rapper’s Delight” (Sugarhill Gang, 1979) first received radio play.

1

In his

memoir Mo’ Meta Blues (2013), Thompson recalls wondering whether he should

remain in front of the radio to listen, or race for a cassette tape to record as much

of the song as he could. He opted to grab the cassette, recalling that “[the song]

sounded like it might go on for another five or six minutes” (23). Thompson’s

gamble paid off: the song did go on for a while longer, and he was able to record

some of it. The original 12” single of “Rapper’s Delight” runs for an astounding

14 minutes and 36 seconds, making it one of the longest songs to ever chart on

the Billboard Hot 100.

While few have been anywhere close to as long as “Rapper’s Delight,”

charting hip-hop songs have used a variety of formal sequences, some of which

substantially differ from the verse-chorus paradigm that has pervaded various

popular music genres since the 1960s. Salt-n-Pepa’s 1987 hit “Push It” peaked at

number 19 on the Billboard Hot 100. This song features lengthy ad-lib vocal

sections and instrumentals while squeezing in two verses almost as an

afterthought. More recently, Kanye West and Jay-Z’s collaboration on “Otis”

(2011) earned them a Grammy Award and substantial chart success; this song is

strophic (it lacks chorus sections), a formal paradigm that has all but disappeared

from popular music.

2

“Rapper’s Delight” was released in hip-hop music’s

nascency—no formal “norms” existed yet, at least not in the recorded medium.

“Push It” emerged during the genre’s so-called Golden Age, when

experimentation was generating a flourishing stylistic diversity in hip hop. And

“Otis” came out when hip-hop music was on its way to becoming synonymous

with mainstream popular music: inter-generic permeability was becoming—and

remains today—the norm.

3

Over time, the formal structure of hip-hop music has

become consolidated in the verse-chorus image of mainstream popular music.

But how did hip hop’s formal conventions evolve—from “Rapper’s Delight” to

94

the present day—and what can this evolution tell us about the mainstreaming of

this genre?

This paper explores the evolution of song form in North American

recorded hip-hop music, tracing the genre’s origins as a live musical practice,

through its commercial ascent in the 1980s and 1990s, to its ubiquity in—and

dominance of—mainstream popular music in the twenty-first century. I conduct

an analytical study of form across 160 hip-hop songs (see the appendix) released

since 1979 to support the three main contributions of this paper. First, I offer a

taxonomy of song section types, investigating how texture, timbre, lyrics, and

singing function as the main agents of formal sectionality in hip hop. I codify

two principal section types, verse and hook (similar, but not identical to a chorus

section), and two looser-defined section types, instrumental, and loose-vocal,

using song examples to illustrate each section type and to discuss these sections’

musical function and/or origins in live performance practice.

Second, I present three formal paradigms that are built up from these four

section types, proposing that the form of many, if not most, hip-hop songs can

be described using one of these paradigms. I classify these as verse-hook, strophic,

and long verse. I evaluate how the paradigms reflect live hip-hop performance

practice (including battling, hyping, and the cypher) and its antecedents: the live

hip-hop performances of 1970s New York (which gave rise to hip-hop music)

and the African American oral tradition of toasting (long, recited poems). In

doing so, I propose a viewpoint that considers hip-hop form through the cultural

underpinnings of this genre, rather than in the image of song forms used in other

popular music genres.

Finally, I investigate how a gradual shift in focus toward verse-hook songs

can be understood in relation to hip-hop music’s ongoing mainstreaming. I

propose three metrics to gauge this shift in focus: the emergence of hooks as a

distinct section type, the rise in popularity of sung hook sections (including by

guest artists), and the specific characteristics of hook sections: their quantity,

their point of first arrival in a song, and their proportion of the song’s total

duration. Viewing hip-hop music’s development through the lens of song form

thus represents both its roots in African American vernacular culture and

assimilation into mainstream popular culture; following blues, R&B, rock ‘n’ roll,

soul, and other genres in traversing this path.

Hip hop’s crossover has been discussed from a variety of perspectives.

Nelson George (1988) and Mark Anthony Neal (2005) have written about the

schism that occurred in the 1980s whereby some Black artists became massively

successful through their new appeal to white mainstream audiences (such as

95

Michael Jackson or Lionel Richie) while alienating their earlier—mostly Black—

fanbase. Amy Coddington (2018) has explored the role of radio producers as

tastemakers in cultivating a divide between the pop-rap of MC Hammer and

Vanilla Ice and the underground music of A Tribe Called Quest and other

Golden-Age artists. Murray Forman (2002), Roni Sarig (2007), and I (2019) have

each investigated the vanishing idea of space and place in hip-hop music as it has

become increasingly mainstreamed. And numerous others, among them Jeff

Chang (2005) and Loren Kajikawa (2015), have noted the increasing

consumption of hip-hop music by white audiences.

4

My aim is to build on this

discussion of hip-hop’s mainstreaming by focusing on song form; more

specifically, the ever-expanding role of the hook section in hip-hop music. The

hook’s increasing prevalence, its earlier placement in song forms, and its

incorporation of singing all evince hip hop’s subsumption by mainstream pop

music.

Song Sections and their Functions

Hip hop is like most other popular music in that its formal sections are ordered

in a song to imbue it with variety, contrast, and some degree of trajectory. I

characterize song sections in hip hop by whether they participate in the core

sequence of a song, or function as framing areas to this core. The core sequence

of a song normally involves verses and hooks, but may also include instrumental

or bridge-like sections. Framing areas normally involve sections with looser

organized vocals (such as ad-hoc “hype” vocals) or instrumental sections. The

main difference between the core sequence and its framing areas concerns the

tightness of sectional organization: core sequences are normally the more tightly

organized of the two.

5

Research on form in popular music has grown substantially since 2000,

but almost none of it explicitly deals with hip-hop music.

6

Corpus studies by Jay

Summach (2012) and Jeffrey Ensign (2015) study song form in a broader array

of popular music—using Billboard charts as corpus sources—but such charts

have traditionally excluded hip-hop music.

7

Scholarship on form in popular

music has expanded to include specific formal paradigms (Spicer 2004, Osborn

2013), artist-specific research (Covach 2006, Stephan-Robinson 2009), song

sections (Attas 2015, Summach 2011), and genres such as EDM (electronic dance

music) (Iler 2011, Osborn 2019, and Barna 2020). Research on form in EDM sets

important precedents for the present study. First, EDM songs are composed to

create and moderate the flow of energy on the dance floor; the formal design of

96

this music does not always lend itself well to the context of radio play.

8

EDM’s

practical function as a dance-oriented music resonates strongly with early hip-

hop music, whose main context of dissemination was at dance-infused

gatherings. Second, EDM song forms rely more on musical parameters such as

texture and timbre, and less on melody and harmony. This again suggests

parallels with hip-hop music, which has traditionally foregrounded aspects of

texture, rhythm, and timbre.

9

The above scholarship provides a blueprint for how a bottom-up (rather

than top-down) study of form in hip hop might look: a taxonomy and

description of song section types according to their internal characteristics, an

examination into how these sections function in a complete song, and whether

any formal paradigms arise. Nearly all hip-hop songs feature some combination

of verses, hooks, and instrumental sections, and share similarities with formal

paradigms used in other popular music. Although I define these section types

according to their internal musical and lyrical characteristics, their functionality

or “effect” they express to the listener (after Doll 2017, 8–9) in songs can vary.

10

In general, verse and hook sections conform to specific musical and lyrical

criteria and express consistent functionality within a song, while instrumental

and loose-vocal sections are less standardized in their content and

functionality.

11

Verse

Verses have been a constant fixture in recorded hip-hop music since its

inception; they facilitate the song’s main narrative arc (if one exists) or provide

commentary on the song’s thematic topics. As in popular music, hip-hop verses

are usually “lyrically variant but musically invariant” (Ensign 2015, 27), meaning

that each successive verse utilizes new lyrics and flow rhythms over the same

beat. Michael Berry (2018) writes that the 16-measure verse has become the

standard length in hip-hop music.

12

The ubiquity of even-numbered verse

lengths is unsurprising: since rhymes normally punctuate the ends of measures

and rhymes are often patterned in couplets, it follows that the mensural length

of most verses will be a multiple of two.

13

Although even-numbered verse lengths

may be common, my data suggests that they also vary widely in length.

Berry also notes that the beat layer (what he calls “the music”) typically

remains unchanged across a verse, often repeating a looped sequence that may

be one, two, or four measures in length (and occasionally longer).

14

Exceptionally, the beat layer’s texture can also gradually change or intensify

97

through the course of a verse. It may also contrast the musical texture of the hook

section, drawing another similarity to other genres of popular music. Example 1

demonstrates some of these characteristics in the beat for “Hard Piano” (Pusha

T, 2018), where textural elements are periodically introduced and removed. The

piano/drum sample from “High as Apple Pie – Slice II” (Charles Wright and the

Watts 103

rd

Street Rhythm Band, 1970) is supplemented first by a drum machine,

and then by a synthesizer-generated chord progression.

Example 1: “Hard Piano” (Pusha T, 2018). The excerpts above detail the different textural

layers that are introduced during the introduction and first verse of the song.

Hip-hop verses are forums for MCs to orate, narrate, display musical and

lyrical dexterity, and connect with listeners. Their varied length, quantity, and

rhythmic and lyrical content may reflect a number of a priori factors: how they

were composed and recorded in-studio, how a live-based performance practice

influenced their construction, or what demands (often commercially driven)

were imposed by record labels or other industry actors. Consider, for example,

“Roxanne’s Revenge” (Roxanne Shanté, 1984) and “NY State of Mind” (Nas,

1994). Both songs feature exceptionally long verses, which may signal looser

organization than in songs with consistent 16-measure verses. But these long,

irregular verses make more sense when considered in the context of how they

were recorded. Shanté allegedly recorded “Roxanne’s Revenge” completely

98

freestyle (unrehearsed and uncomposed) and in a single take; a herculean feat

for any MC, much less a 13 (!) year old with no prior recording experience.

15

“NY

State of Mind” features two long verses of different lengths; but these were also

recorded in a single take.

16

The spontaneity that permeated the recording of these

verses arguably influenced their length: in Shanté’s case, the long duration, and

in Nas’s case, the variance in duration between verses.

Hook

Hook sections in hip-hop music are somewhat analogous to choruses in other

popular music genres: their lyrics usually remain fixed over the course of the

song, quote or hint at the song’s title, and often contrast the function of the verse

lyrics. Hook sections normally comprise a single, self-contained section, but two-

part hooks are occasionally used, such as in “Money Ain’t a Thang” (Jermaine

Dupri ft. Jay-Z, 1997), where the first part of the hook begins on the lyrics “In

the Ferrari” and the second part on “Y’all wanna floss with us.”

17

If the verse

involves narrative, the hook might comment on that narrative. In protest-based

songs, the verse may describe an issue while the hook incites a call to action.

18

Hook lyrics can be rapped or sung, and, until recently, the hook was normally

the sole location for singing in hip-hop songs.

19

I prefer to call these sections hooks (instead of choruses) because, while

their functional role may parallel choruses in popular music, they fulfill this role

in different ways.

20

I agree with Paul Edwards’s statement that hip-hop hooks are

“designed to ‘hook’ the listeners” (2009, 187) and propose that they do so

through a level of lyrical repetition and fragmentation not normally seen in

popular music—an extreme example would be “Gucci Gang” (Lil’ Pump, 2017),

where the title lyric is rapped no fewer than 20 times in each hook. Furthermore,

hip-hop hooks do not rely on many of Temperley’s features of chorus sections

(2018, 160), especially those concerning melodic and harmonic parameters as

well as formal ordering. Instead, hip-hop hooks—when defined against

characteristics of verses—are built on subtle textural shifts, the presence of

singing, sampled or instrumental riffs in the beat layer, and the aforementioned

fragmentation. While some songs feature sung hooks that sound remarkably

similar to a standard pop chorus—such as “Juicy” (The Notorious B.I.G., 1994)—

others feature incessant repetition of title lyrics, such as “93 Til’ Infinity” (Souls

of Mischief, 1993). Still others have hardly any lyrics at all, and an instrumental

motif assumes central importance, such as in “Grindin’” (Clipse, 2002).

99

In my taxonomy I call on several criteria for defining hook sections. First,

a hook section contains intelligible vocals—either sampled, rapped, or sung.

Second, these vocals usually reference the title of the song or are repeated and

fragmented.

21

Third, the hook section remains musically and lyrically invariant

throughout the song, usually (but by no means always) alternating with verses.

Another criterion of hook sections involves their textural distinction (I stop

short of conflating this with intensification or thickening) from the verses.

22

While many of these stylistic features are also ubiquitous in pop choruses, the

near-total lack of melodic and harmonic differentiation between verses and

hooks in hip-hop music, combined with the greater emphasis on fewer, more

repeated lyrics, warrants a separate definition of the hip-hop hook that

distinguishes it from the pop chorus.

23

Instrumental

Beyond verses and hooks, other song sections in hip-hop music are less

consistent in their content and functionality. While it might seem

straightforward to define instrumental sections by virtue of them lacking live-

performed vocals, their texture and musical content occasionally position them

well to function as hook sections. In this sense then, category and function

diverge for instrumental sections. These sections involve only the beat layer; no

live-performed vocals are present. The beat layer comprises a combination of

instruments, computer-produced sounds, scratching or other turntable-

generated sounds, and samples. Samples may involve vocals, and paradoxically,

instrumental sections may actually contain vocals by virtue of their participation

in the beat layer. But these vocals are unintelligible: they may be short fragments,

scat singing, or other brief utterances. If the vocal samples involve intelligible

lyrics, it is more likely they are imbuing the section with a hook-like quality, and

could thus be interpreted as hook sections.

Amanda Sewell writes that “lyric [vocal] samples have many different uses

and applications in sample-based music: layered against newly-rapped lyrics in

an adjunct function, scratched into a track’s introduction or an interlude

between verses, or substituted into a rapped lyric” (2013, 54).

24

Vocal samples in

an “interlude between verses” quite often contribute appreciably to the song’s

lyrics, either by referencing the song’s title or commenting on the song’s

narrative or theme in some way. Vocal samples may thus participate in

establishing the hook-like quality in a song section, especially when the vocal

samples reference the song title, such as in “Watch Me Now” (Ultramagnetic

100

MCs, 1988) or “Hold It, Now Hit It” (Beastie Boys, 1986). By contrast,

unintelligible vocal samples carry less potential to imbue such hook-like

qualities. In “It Ain’t Hard to Tell” (Nas, 1994), verses alternate with sections that

feature a denser beat-layer texture, a sampled saxophone riff, and sampled female

scat vocals. These sections are almost hook-like, but for their lack of intelligible

vocals I classify them as instrumental. These three songs expose an inconsistency

with how instrumental sections function: when they are positioned between

verses, their internal content—especially vocal samples—may cause them to

express hook-like qualities of varying strength and salience.

The opening thirty seconds of “Watch me Now” illustrate this blurry

boundary by juxtaposing different types of vocal samples. The first 18 seconds

contain numerous whoops and cries originally performed by James Brown; some

of his signature vocal gestures.

25

But these vocal samples are unintelligible as

lyrics, and thus help define this introduction as an instrumental section (0:00–

0:18). Immediately following this section, the “Watch me Now” sample (from

“It’s Just Begun” by The Jimmy Castor Bunch [1972]), imbuing the section with

hook-like qualities, helping define 0:19–0:27 as a hook (indeed, it is the “Watch

me Now” section that returns after each verse). By attending to the varied

intelligibility and narrative function that vocal samples may exhibit, I thus

interpret them as alternately contributing to instrumental or hook sections. The

looser-knit nature of instrumental sections and their variegated placement

within song forms suggests a wider array of functional purposes for them,

including dancing, repose from the vocals of the verses and hooks, and a space

to showcase the musical contributions of DJs and beat producers. Indeed, hip

hop’s earliest musical manifestations showcased beats, along with their creators;

rapping came later.

Looser-Organized Vocal Sections

Live-recorded vocals in hip-hop music are not restricted to verses and hooks:

looser-organized sections may contain ad-hoc, ametric vocals, skits, or may

simply involve rapping or singing in a section that does not function like a verse

or hook. Many songs feature ad-hoc vocals that characterize sections in their

framing areas, but less often within the core sequence. These ad-hoc vocals

occasionally function as “hype” vocals: ametric vocals that usually serve the

rhetorical purpose of enhancing anticipation of the song’s main lyrical content.

A prominent example of hype vocals in hip-hop music can be found in the music

of Public Enemy, where group member Flava Flav effectively functions as a “hype

101

man.”

26

Other ad-hoc vocals might be less hype-based and more about

connecting directly with listeners or other artists. These may include “shout out”

sections (normally at the end of songs) or more introspective lyrics performed in

an ametric fashion, such as when Anderson .Paak discusses his personal finances

(0:50) in “CUT EM IN” (2020). Ad-hoc vocals are noticeably more common in

hip-hop music than they are in other popular genres. They are so common, in

fact, that this type of vocal also appears within and throughout verses and hooks

(a notable example being producer Sean Combs’s frequent vocal injections in the

rapped performances of Notorious B.I.G.). This prevalence likely has much to

do with hip hop’s origins as a live musical genre centered around the DJ (who is

now commonly referred to as the producer). The outdoor hip-hop parties of

1970s and early 1980s Bronx and Queens featured the DJ as performer; any

vocalizing was usually done by the DJ, or in deference to them.

27

This vocalizing

was not the main focus and was ad-hoc or spontaneous in nature. As hip hop

established a tradition of recorded musical output, the hype/ad-hoc vocals

remained a central part of some artists’ personal styles.

28

As can be seen from the

aforementioned types of looser vocal practices in hip-hop music, loose vocal

sections are highly variegated and serve a variety of different musical functions.

I have established flexible descriptions of four main types of song section

in hip-hop music. This framework allows for a systematic encoding of song

forms across a large corpus of repertoire. These encodings in turn reveal several

prevailing formal paradigms in hip-hop music. The next section explores these

paradigms, proposing some possible locations and trajectories for their

development.

Formal Paradigms

To better understand how sections combine to create whole songs in hip hop, I

draw on a recent corpus study where I analyzed 160 songs released between 1979

and 2017 (Duinker 2020). This corpus was generated from two source lists:

Rolling Stone’s “100 Greatest Hip-Hop Songs,” and the Grammy Award category

for Best Rap Song. While my main analytical goal was to investigate aspects of

rhythm and meter, I also annotated each song’s form by section type and

duration. Example 2 displays my annotation method for the song “Hate It or

Love It” (The Game ft. 50 Cent, 2005). “Hate It or Love It” begins with a nine-

second ad-lib vocal section followed by a series of verses and hooks performed

by the song’s two MCs, The Game and 50 Cent. From 2:53 until the song’s

conclusion, the beat layer continues with no vocals from either MC—there is,

102

however, a female vocal sample embedded in the beat layer that does not

contribute appreciably to the song’s lyrics. I have thus encoded this final section

“instrumental.” The annotation of “Hate It or Love It” reveals a commonality in

hip-hop form: hook sections are typically the same durational length across an

entire song, while verses are more likely to vary in length.

Formal Region Section Type

Elapsed Time Duration (s) Notes

framing area voc 0:00 9 50 Cent (hype vocals)

core sequence

vs1

0:09

28

50 Cent

hk 0:37 21

vs2 0:58 37 The Game

hk 1:35 20

vs3

1:55

38

50 Cent and The Game

hk 2:33 20

framing area inst 2:53 33 includes fadeout

Example 2: Formal annotation for “Hate It or Love It” (The Game ft. 50 Cent, 2005). Section-

type abbreviations are used as follows throughout this paper: voc = loose vocal section, hk =

hook, vs = verse, and inst = instrumental. All sectional durations documented here should be

interpreted +/- one second: durations were calculated from real-time elapsed time

measurements, meaning slight inaccuracies in the order of one second were common.

The song’s form is straightforward: “Hate It or Love It” features discrete

framing areas and a tangible core sequence of verses and hooks. But many other

songs exhibit more irregular forms. Consider the original 12” release of “Push It”

(Salt-n-Pepa, 1987), whose form is annotated in Example 3. The song’s first verse

appears at 1:31—this is quite late for a first verse—and besides a few other verses

and hooks, the remainder of the song is loosely organized: the entire duration

leading up to the first verse, for example, is an amalgam of instrumental passages,

hype vocals, and chanting. No clear sectionality emerges here, yet no one section

type (of my four) is clearly established. I have therefore chosen to denote this a

hybrid of instrumental and looser vocal section types (hence “inst/voc” in the

annotation). Such hybrid sections appear to be common in framing areas, but

their outsized presence as in “Push It” (the framing areas make up 60% of the

song’s duration) is rare. As a party-oriented song, “Push It” features these

extended loose sections primarily to aid the song’s danceability.

29

“Push It” thus

reveals the importance of considering performance context and function of

songs when evaluating the sectionality of their forms.

103

Formal Region Section Type

Elapsed Time Duration (s) Notes

framing area inst / voc 0:00 91 features hype vocals

core sequence vs1 1:31 16

hk 1:47 13

inst / voc

2:00

27

vs2 2:47 12

hk 2:59 16

framing area inst / voc 3:15 77 includes fadeout

Example 3: Formal annotation for “Push It” (Salt-N-Pepa, 1987). The “inst/voc” sections are

so named for their hybridity—they integrate aspects of instrumental and loose vocal section

types—and are notable in their comparatively long duration.

The remainder of this section is organized around three prevailing formal

paradigms: strophic form, verse-hook form, and long-verse form.

Strophic Form

Strophic-form songs generally feature a core sequence comprising multiple

verses that either proceed in immediate succession or are interspersed by

instrumental interludes. Such interludes typically lack hook-like qualities.

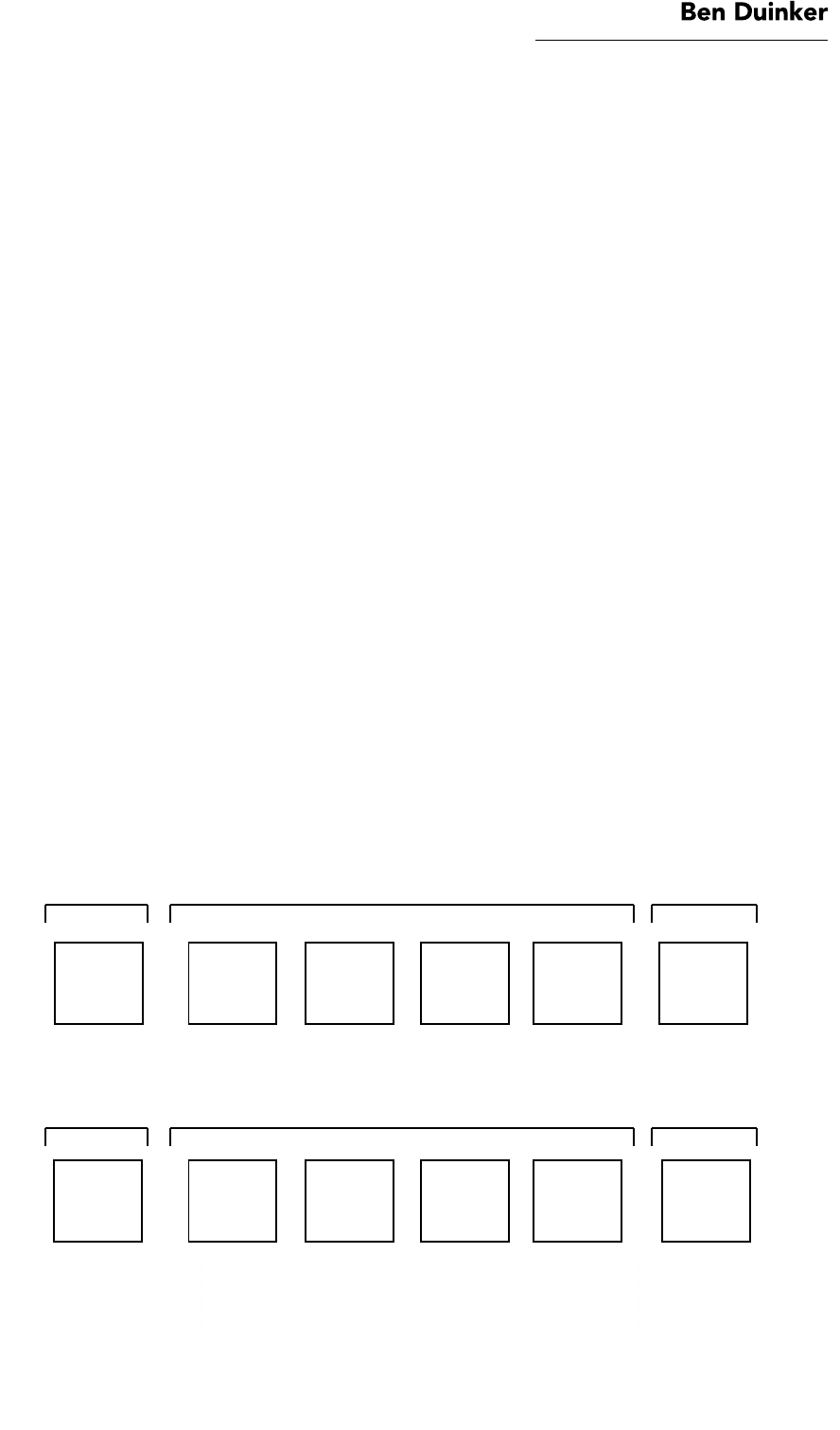

Example 4 provides a general schema for strophic forms in hip hop. Notable in

strophic-form songs is the near-total absence of hook sections; in this way,

Example 4: General schema for strophic-form songs. These songs typically include a core

sequence that is bounded by framing areas. The core sequence may include a succession of

verses (upper diagram), or a succession of verses interspersed by instrumental sections (lower

diagram).

Core SequenceFraming Area Framing Area

VerseIntro OutroVerseVerse

Core SequenceFraming Area Framing Area

VerseIntro OutroVerseVerse

Instrumental Instrumental

104

strophic form is quite similar to Covach’s “simple verse form” (2004, 73).

30

The

long single version of “Rapper’s Delight” (Sugarhill Gang, 1979) constitutes a

textbook example of strophic form. An instrumental section begins and

concludes the song, framing the core sequence of four verses rapped in

immediate succession.

31

“King of Rock” (Run-DMC, 1985) follows a slightly

different trajectory. With no introductory framing area, the first verse begins

immediately at the song’s outset. The eight verses of this song are always followed

by instrumental sections of varying lengths, laden with rock guitar soloing; the

alternation of these sections makes “King of Rock” a strophic-form song.

While parallels can be drawn between the strophic-form hip-hop songs

and the “simple verse” and “AAA” forms used to describe other popular music,

I hesitate to use such parallels as a defining characteristic of strophic hip-hop

songs. I prefer instead to contextualize strophic form in the tradition of live hip-

hop performance. An important aspect of hip hop’s performance tradition is the

cypher: an informal group-performance context where various MCs take turns

freestyling either atop a DJ-produced or beatboxed beat, or a cappella.

32

Michael

Newman describes cyphers as involving “improvised round-robin rapping”

(2005, 401), while H. Samy Alim qualifies them as “highly competitive lyrical

circles of rappers” (2006, 6). James Braxton Peterson (2014) and Roderick

Pullum (2019) have suggested that the term “cypher” emerged into common hip-

hop parlance through the influence of the Five-Percent Nation.

33

Though cyphers typically have no set requirements regarding the number

of MCs participating or the length of their verses, the general form they follow

involves the introduction of a beat followed by a succession of freestyle verses,

rapped by different MCs. The musical and lyrical foci of cyphers are intertextual

references, unifying chains of rhymes, and communication between MCs in the

cypher (such as calling one another by name to spit the next verse, or through

put downs). Hooks generally play no important role in cyphers. While the cypher

is a less formal, live performance practice, its analogy in recorded hip-hop music

can be seen through the “posse cut,” which is a song that features different

rappers (usually associated with one another, occasionally through a common

record label) on each verse. Several well-known posse cuts appear in the corpus,

“Scenario,” “The Symphony” (Marley Marl et al., 1989), “Flava In Ya Ear

(Remix)” (Craig Mack et al., 1995), and “Fuckin’ Problems” (A$AP Rocky et al.,

2013) among them.

34

“The Symphony” represents perhaps the truest

resemblance to a cypher of these posse cuts: a brief intro featuring Marley Marl

is followed by successive verses rapped by Masta Ace, Craig G., Kool G Rap, and

105

Big Daddy Kane, respectively, each MC concluding his verse by naming the next

MC who is due up to rap.

By drawing parallels between cyphers, posse cuts, and strophic form, I aim

to show that, in live hip-hop performance practice, the lyrical, structural, and

musical focus of the song is often centered around the verse. Verses are what

cyphers and rap battles (another chief format for freestyling) are made of. Verses

figure prominently in strophic hip-hop songs. And verses are the platform across

which a collection of MCs come together to contribute to posse cuts. The verse—

however it is structured—is the main conduit of communication and exchange

in hip-hop performance, and its centrality to the cypher, posse cut, and strophic-

form song traces a through-line between these practices.

Verse-Hook Form

Verse-hook form chiefly involves what its name suggests: verses and hooks. The

general schema of verse-hook form is detailed in Example 5. Like the verse-

chorus paradigm referenced by Covach (2004), Temperley (2018), Ensign

(2015), and others, verse-hook songs in hip hop feature a core sequence of

alternating verse and hook sections. This sequence occasionally includes

instrumental or loose-vocal sections, but my corpus data suggests that such

interventions are uncommon. Rarer still are verse-hook songs where multiple

verses or multiple hooks (these could perhaps also be characterized as two-part

hooks) occur in immediate succession.

Example 5: General schema for verse-hook songs. The chief variable in these songs involves

the ordering of verses and hooks, as shown between the two formal trajectories above.

Core SequenceFraming Area Framing Area

VerseIntro OutroVerseHook

Core SequenceFraming Area Framing Area

VerseHook

Hook

VerseHookIntro Outro

106

Three songs encapsulate these various affordances of verse-hook form. In

Example 6a, the formal sequence of “99 Problems” (Jay-Z, 2003) constitutes a

textbook example of a verse-hook form. A brief a cappella rapped introduction

previews the hook lyrics, before the core formal sequence runs through three

verses, each followed by a hook.

35

The song concludes with an instrumental

section—repeated iterations of the basic beat loop—complemented by various

hype vocals.

By contrast, “Lose Control” (Missy Elliott, 2005), shown in Example 6b,

features loose-vocal framing sections (mainly featuring hype vocals by Fatman

Scoop) and a core sequence that contains two pairs of verses and hooks. Loose

vocal sections occur after the first hook and again after the second verse. The first

of these features guest artist Ciara in a rapped/sung performance: more metric

than hype vocals normally are, but less tightly organized than Elliott’s verses and

hooks. The second loose vocal section features a repeated chant-like

performance by Elliott and Fatman Scoop.

36

Finally, the radio edit of “Ladies First” (Queen Latifah ft. Monie Love,

1989) as detailed in Example 6c involves a verse-hook core form (with no

framing sections) that features a changing number of verses between each hook.

The four hook sections in this song appear at the opening, after verse 2, verse 4,

and verse 7, respectively. This means the song’s eight verses appear in groups of

two, two, and three. While “Ladies First” and “Lose Control” depart from the

schema shown in Example 5, the general alternation of verses and hooks in their

core sequences identify these songs as verse-hook forms.

Formal Region Section Type

Elapsed Time Duration (s) Notes

framing area

hk

0:00

6

features hook lyrics

core sequence vs1 0:06 40

hk 0:46 11 shorter than other hook

sections in the song

vs2 0:57 62

hk 1:59 20

vs3 2:19 52

hk 3:11 21

framing area inst / voc 3:32 23 hype vocals

Example 6a: Formal annotation for “99 Problems” (Jay-Z, 2003). This song features discrete

framing areas and a balanced core sequence of three verses and three hook sections. Within

the core sequence, the first hook section is notably shorter than the following two.

107

Formal Region Section Type

Elapsed Time Duration (s) Notes

framing area voc 0:00 18 hype vocals

core sequence vs1 0:18 32

hk 0:50 14

voc 1:04 17 rapped / sung

vs2 1:21 30

voc 1:51 16 chanting

hk 2:07 13

framing area voc 2:20 87 chanting

Example 6b: Formal annotation for “Lose Control” (Missy Elliot ft. Fatman Scoop and Ciara,

2005). A number of different loose-vocal sections feature in both the framing areas and core

sequence.

Formal Region Section Type

Elapsed Time Duration (s) Notes

core sequence

hk

0:00

22

short instrumental tag

at end

vs1

0:22

14

vs2

0:36

18

hk 0:54 4

vs3 0:58 18

vs4 1:16 18

hk 1:34 16

vs5 1:51 18

vs6 2:09 35

vs7 2:44 18

hk 3:02 20

vs8 3:22 20

(framing area) inst 3:42 8 quick fade out

Example 6c: Formal annotation for the radio edit of “Ladies First” (Queen Latifah ft. Monie

Love, 1989). This version of song, while verse-hook in composition, avoids an introductory

framing section and features differing numbers of verses between each hook. Its core sequence

also begins with a hook and concludes with a verse, a formal ordering not common in rock/pop

music (Temperley 2018) but quite prevalent in hip-hop music.

Example 5 also indicates that the core sequence of verse-hook songs may

begin with either a verse or a hook. This flexibility departs from the formal

conventions of rock-pop music, where a song’s first verse is likelier to occur

before its first chorus.

37

Temperley (2018) has classified the ordered pairing of

verses and choruses as “verse-chorus units,” or VCUs, generating a more

efficient way to encode the form of many pop songs. While it is tempting to apply

108

the VCU concept to hip-hop music, perhaps with the alternate acronym VHU

(verse-hook unit), the directionality embedded in the VCU concept implies that

the verse normally comes first.

38

This assumes that the verse points toward the

hook/chorus, which can be achieved through harmonic, textural, melodic,

lyrical, or other means. Such explicit directionality between verses and hooks (in

that order) is by no means paradigmatic in hip-hop music.

39

“Hypnotize” (The

Notorious B.I.G., 1997) exemplifies the non-teleological relationship between

verse and hook, the form of which is detailed in Example 7. While the song’s core

sequence is indeed ordered verse-hook (and not the other way around), a

number of lyrical and textural features mask any sense of buildup or

directionality from each verse into its following hook. First, the beat’s texture

does not change between these two section types. The basic beat loop is quite

sparse, consisting only of a two-measure loop performed by bass and drums. A

momentary guitar flourish marks each eight-measure hypermetric unit,

providing some structural waypoints amid the decidedly complex metric

patterning of The Notorious B.I.G.’s (henceforth Biggie) flow.

The first verse is 18 measures long, meaning the hypermetric guitar

flourish occurs for a third time, in m.17. Instead of marking the beginning of a

new, unfolding, eight-measure hypermetric unit, this flourish punctuates the last

two measures of the verse, after which the hook arrives with no hypermetric

Example 7: Basic beat loop and formal annotation for “Hypnotize” (The Notorious B.I.G.,

1997). The first and second verses each run for 18 measures. As shown for the first verse, this

mensural length creates a misalignment with the hypermetric structure jointly generated by

iterations of the 2-measure beat loop (small x) and guitar flourishes (capital X), which repeat

after 8 measures.

Measure 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

Guitar Flourish

X

X

X

Beat Loop x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

Song Section verse 1

Measure 19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

Guitar Flourish

X

Beat Loop x

x

x

x

Song

Section

hook

109

markers. Biggie’s flow performance also contributes to the anticlimactic

conclusion of the verse. In the first verse in particular, his flow patterns and

choice of lyrics create a dense, complex web of possible groupings, depending on

whether rhythm, meter, lyrical syntax, or subject matter is considered.

40

This

lyrical complexity makes it difficult to anticipate closure at the end of the verse.

As a consequence, when Biggie raps “Packin, askin’ ‘who want it?’ / You got it,

nigga, flaunt it, that Brooklyn bullshit, we on it” at the beginning of m.17, not

only has the guitar flourish made this passage sound like an initiating gesture in

a new eight-measure unit, but the flow gives no solid indication of conclusion. It

simply ends; a string of rhyme chains, backward and forward lyrical references,

and segues in subject matter, all quietly and unmarkedly yield to the hook

section.

Long-Verse and Other Forms

Strophic and verse-hook songs constitute the vast majority of the corpus. Of the

160 songs represented, 123 (77%) are verse-hook while a further 24 (15%) are

strophic. The remaining 13 (8%) either feature a single long verse (long-verse

form) or follow a formal path distinct from the paradigms discussed here.

“Roxanne’s Revenge” (Roxanne Shante, 1984), “Paid in Full” (Eric B. & Rakim,

1987), “Children’s Story” (Slick Rick, 1988), and “Brooklyn Zoo” (Ol’ Dirty

Bastard, 1995) are all examples of long-verse forms. Each begins with an

introductory framing area, contains a core sequence of one long verse, and

concludes with either a hook-like section, ad-hoc vocals, or instrumental section.

The long-verse form draws to mind an earlier type of Black American vernacular

oral tradition: the toast. Toasts were long poems that were delivered in an

informal style.

41

These long poems usually featured some sort of trickster figure

(i.e. Shine or the signifyin[g] monkey) surmounting odds that are stacked against

them; hustling their way through the narrative.

42

Classic examples of toasting set

to music include Gil-Scott Heron’s “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised”

(Pieces of a Man, 1970), and Rudy Ray Moore’s “The Signifyin’ Monkey” (This

Pussy Belongs to Me, 1971); indeed, both these performers have been cited as

stylistic precursors to hip-hop music.

43

Philadelphia-based Schooly D’s version

of the toast The Signifyin’ Monkey (“The Signifyin’ Rapper,” 1988) is perhaps the

truest example of a toast being performed in a hip-hop setting in that it literally

adapts a toast (but does not exclusively feature metric rapping), and “Children’s

Story” (Slick Rick, 1988) is an example of how the toast concept has been fully

adapted into a rapped performance. “Children’s Story” flips the toast convention

110

on its head, instead purveying a cautionary tale where the hustling protagonist

does not come out on top; indeed, he ends up dead. Long-verse songs follow a

number of narrative arcs that relate back to toasts: the verses in “Roxanne’s

Revenge” and “Brooklyn Zoo” are both diss-laden and self-aggrandizing.

44

While

tropes of put-down and self-aggrandization are certainly ubiquitous to hip-hop

lyrics in general, when they pervade a long-verse song’s lyrics, two key elements

of toasting are reflected in a hip-hop performance.

Section Type Elapsed Time Duration (s) Notes

voc

0:00

10

hype vocals

inst 0:10 8 introduction of beat layer

hk? 0:18 12 unclear section type

inst 0:30 17

vs1? 0:47 39 unclear section type

inst 1:28 17

voc 1:43 17

inst 2:00 17

hk 2:17 12

inst 2:29 17

voc 2:46 17

inst 3:03 34

hk 3:37 13

inst 3:50 90

voc 5:20 17

vs2

5:37

38

inst 6:15 90

Example 8: Formal annotation for “The Breaks” (Kurtis Blow, 1980). The varied sectional

ordering of this song, as well as its divergent section lengths (notably the two 90-second

instrumental sections toward the end) render it difficult to classify as “verse-hook” or

“strophic.” Identification of framing areas and the core sequence is complicated by the

sectional ordering. One might interpret the core sequence as beginning at 0:18, but quantity of

instrumental and loose-vocal sections weakens its ability to function as such, with standard

alternations between verses and hooks or instrumentals.

In the corpus, songs with formal sequences classified as “other” were

very few, although they warrant mention on the grounds of their functional

purpose. Two notable “other” songs include “The Breaks” (Kurtis Blow, 1980)

and “Push It” (Salt-N-Pepa, 1986); these both fall into the Adam Krims’s genre

of “party rap,” which he describes as being “designed for moving a crowd,

making them dance, or perhaps creating or continuing a ‘groove’ and a mood”

(2000, 55). Listening to either of these songs with this description in mind

111

makes the “party rap” designation seem obvious for both of these songs, and

also suggests why such songs rely less on a tightly organized structure of verses

and hooks. As shown in Example 8, the formal patterning of “The Breaks”

looks something like verse-hook, but includes a number of instrumental breaks,

two of which are each 90 seconds long. These extended looser sections reveal

the primary function of the song: a medium for dancing. Rather than suggest

that dance-functioning music cannot contain verses and choruses, I use these

examples to illustrate that instrumental sections can (and often do) figure just

as prominently as verses or hooks in party-, or dance-oriented hip-hop songs.

Form and the Mainstreaming of Hip Hop

The mainstreaming of hip-hop music has been discussed in context of the radio’s

role as tastemaker (Coddington 2018), the influence of Billboard chart

categorizations (Harrison and Arthur 2011), and the appropriation of Black

musical traditions and culture (Neal 2005 and George 1988). Coddington argues

that top-40 radio station producers, in order to reach their targeted

demographics, preferred to play hip-hop records that mainstream audiences

could understand and tolerate. The stripped down, aggressive style of artists like

Run-DMC, Public Enemy, and LL Cool J did not fulfill this role, as did the

comparative musical tameness of artists like MC Hammer, Vanilla Ice, and Milli

Vanilli. Coddington aptly observes the growing rift between pop rap and

underground, politically charged rap music that emerged in the late 1980s. She

also notes, however, that the sound world of pop rap eventually permeated hip-

hop music, such that an artist like The Notorious B.I.G. could juxtapose lyrics

about his hard-edged, drug-selling upbringing with a slickly produced beat that

bore closer resemblance to M.C. Hammer than Public Enemy.

This mainstreaming of hip-hop music in the 1980s and 1990s thus appears

to have been a multi-step phenomenon. Firstly, a less controversial, softer brand

of hip-hop music was marketed to a wide demographic. Such marketing

bypassed the more confrontational and political arm of hip-hop music, whose

artists such as Public Enemy and N.W.A. were experiencing their own, smaller

commercial breakthrough. Secondly, more accessible musical styles were

combined with confrontational, profanity-laden, and uncompromising lyrics,

creating an uneasy balance between radio-ready musical accessibility and

provocative lyrical subject matter less well-suited for mass-market radio play—

this combination can be seen in the artists on the Death Row (Dr. Dre, Snoop

112

Dogg, and Tupac Shakur), and the Bad Boy (The Notorious B.I.G. and Lil’ Kim)

labels. This two-phase process eventuated a number of successfully charting

singles by artists such as Shakur and The Notorious B.I.G.—a marker of

mainstream success for this new hybrid of pop-rap beats and hardcore lyrics.

45

How does this process of mainstreaming relate to evolving trends in song

form? To conclude this paper, I present a number of statistic-driven observations

regarding song forms and their evolving usage in hip hop. Each involves the hook

section in some way: a gradual increase in prevalence of verse-hook songs, an

increase in sung hooks, hooks appearing sooner in songs’ formal sequence, and

the proportion of a song’s total length taken up by hooks. In contrast to the verse,

the hook evolved from an infrequently used formal section to a central feature of

nearly every hip-hop song today.

The Emergence of the (Sung) Hook

When “Rapper’s Delight” was released in 1979, it had an immediate and long-

lasting impact.

46

The idea that rapping—as opposed to singing—could be

featured in a radio-worthy song was novel, and this song would play an outsized

role carving out a space in the recording industry for hip-hop music. Musically

speaking, “Rapper’s Delight” was not particularly groundbreaking.

47

The song’s

beat was a recorded interpolation of the song “Good Times” (1979), released

earlier that year by the R&B/disco band Chic.

48

But while “Good Times” contains

an identifiable chorus section, “Rapper’s Delight” does not. Instead, “Rapper’s

Delight” features a string of rapped verses in its core sequence, with instrumental

sections serving its framing areas.

49

While some of the song’s lyrics have hook-

like qualities (such as the opening lyrics by Wonder Mike, “I said-a hip hop,

hippie to the hippie ...,” and Big Bank Hank’s “Hotel, motel …” line), these lyrics

do not form autonomous song sections—they appear within longer verses

performed by those MCs.

“Rapper’s Delight” thus qualifies as a strophic song. Indeed, many other

old-school hip-hop songs (those released in the late 1970s and early 1980s) are

strophic.

50

As documented in the appendix, 15 of the 40 corpus songs released

between 1979–1989 are strophic, while another 15 are verse-hook (the remaining

10 are either long-verse form or do not easily fit any one of the three paradigms).

The contrast between this balance of types and the rest of the corpus is stark:

after 1989, across the remaining 120 corpus songs, only 13 are not verse-hook,

and perhaps most striking is that 10 of these 13 appear before 1996. As far as this

corpus is able to explain general trends in hip-hop form, then, verse-hook form

113

had firmly, and indeed almost exclusively, become the standard paradigm used

in hip-hop music by the mid 1990s.

Popular songs that are expected to do well on the charts are often released

in two versions: a single version (sometimes called the “radio edit”), and an

album version. “Rapper’s Delight” was released in five versions, each with a

different duration, none of which featured a hook section.

51

By contrast, the two

versions of Queen Latifah’s Afrocentric feminist anthem “Ladies First” (1989)

follow markedly differing formal sequences. The album version of this song

features no hook sections, but the radio edit of the song does (the forms are

compared in Example 9); the famous music video for “Ladies First” corresponds

to the radio edit version.

Album Version Radio Edit

Section Type (Elapsed Time) Duration(s) Section Type (Elapsed Time) Duration(s)

inst (0:00) 18 hk (0:00) 22

vs1 (0:18) 13 vs1 (0:22) 14

vs2 (0:31) 18 vs2 (0:36) 18

inst (0:49) 5 hk (0:54) 4

vs3 (0:54) 18 vs3 (0:58) 18

vs4 (1:12) 18 vs4 (1:16) 18

inst (1:30) 36 hk (1:34) 16

vs5 (2:06) 18 vs5 (1:51) 18

vs6 (2:24)

36

vs6 (2:09)

35

vs7 (3:00) 17 vs7 (2:44) 18

inst (3:17) 42 hk (3:02) 20

vs8 (3:22) 20

inst (3:42) 8

Example 9: Comparison of formal sequences in the album version and radio edit of “Ladies

First” (Queen Latifah ft. Monie Love, 1989). Accounting for the one-second discrepancies,

corresponding verses are the same length in each version. An eighth verse and four hook

sections are added in the radio edit, and all instrumental sections (save for a short fadeout) are

removed.

As Tricia Rose (1994) and Robin Roberts (1994) attest in their analyses of

this video, the hook section figures prominently in the song’s advocation of

community among women MCs, and in a more general sense, of solidarity in the

Black feminist movement.

52

The challenging lyrics of the verses, aggressively

rapped (by Latifah and guest MC Monie Love) over a hard-sounding beat,

contrast the gentler-sounding hook, which involves singing and a shift to the

major mode.

53

The addition of the hook section in this radio edit dramatically

114

alters the course, message, and ethos of “Ladies First,” while making it more

musically palatable for radio and television play.

The Sung Hook

The mere presence of a hook does not fully explain its role as mainstreaming

agent; its musical content is equally important to consider. Hook sections in all

23 verse-hook song in the corpus released before 1993 either feature rapping,

sampled vocals (either sung or rapped), or, more rarely, vocals sung by the MC(s)

themselves. Examples of these scenarios include, respectively, Melle Mel rapping

all the hooks in “The Message” (Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five, 1982),

sampled vocals in the hook sections of “Slow Down” (Brand Nubian, 1990), and

the earnest singing by Biz Markie in the hooks of his song “Just a Friend”

(1989).

54

Beginning in the mid-1990s, hip-hop songs started consistently

featuring hooks sung by guest artists: David Ruffin Jr. on “Gin and Juice” (Snoop

Dogg, 1993), members of the girl group Total on “Juicy” and “Hypnotize” (The

Notorious B.I.G. 1994 and 1997), Roger Troutman on “California Love” (Tupac

Shakur and Dr. Dre, 1995), and Reggie Green and Sweet Franklin on “Dear

Mama” (Tupac Shakur, 1995). The juxtaposition of hardcore rap lyrics centered

around crime, drugs, and material wealth with smooth, R&B-style vocals has

been identified by Coddington as central to the commercial success enjoyed by

Puff Daddy and The Notorious B.I.G., and by Krims as a defining feature of don

rap, his term that describes the merging of reality rap (gangsta rap) and mack

rap, which Krims situates as central to the “mack” or “pimp” personas adopted

by certain MCs and groups (2000, 62–63). This occasionally tension-laden

juxtaposition was immensely successful from a commercial standpoint.

55

“Hypnotize” and “California Love” both reached number one on the Billboard

Hot 100, “Dear Mama” and “Gin and Juice” broke the top 10 on the same chart,

and these four songs as well as “Juicy” each reached number one on the Billboard

Hot Rap Songs chart.

Sung hooks—whether recorded by guest artists or the song’s MC(s)—

have remained a fixture in verse-hook songs since the 1990s. But while sung

hooks usually form one of the most memorable parts of a hip-hop song, the

identity of their singers has not always driven this memorability or contributed

to the song’s commercial appeal. Think of the well-known “Biggie Biggie Biggie,

can’t you see?” hook from “Hypnotize” (The Notorious B.I.G., 1997)—itself an

interpolation of “La Di Da Di” (Slick Rick and Doug E. Fresh, 1985). Even though

nearly everyone who listened to top-40 radio or watched MTV in the 1990s will

115

know how this hook goes, very few will likely know who sung it (Pamela Long

from the group Total). These optics have changed dramatically in songs released

in the past two decades. Faith Evans was already a well-known artist when she

sung the hook on “Missing You” (Puff Daddy and Faith Evans, 1997), a song

dedicated to her late ex-husband Christopher Wallace (The Notorious B.I.G.),

but her involvement with Sean Combs and Bad Boy Records arguably raised her

profile more than she did theirs.

56

Guest hooks sung by artists such as Justin

Timberlake, Alicia Keys, and Rihanna—all of whom have garnered wide,

mainstream appeal in their careers—were undoubtedly a commercial boon for

the hip-hop songs on which they appeared.

57

This combination of rapping and

singing in the hip-hop industry has led to a specific Grammy award for “Best

Rap/Sung Collaboration” (now called “Best Melodic Rap Performance”).

By referencing the guest hook paradigm in hip-hop music, I do not mean

to imply that the aforementioned songs would have failed commercially without

their guest features, but rather that the presence of guest pop artists opened up

an avenue toward massive mainstream appeal which would have otherwise been

difficult to attain. While Jay-Z, for example, was already a successful artist and

entrepreneur by the early 2000s (culminating with his critically praised 2003

“retirement album” The Black Album), 11 of his 14 top-five appearances on the

Billboard Hot 100 chart—including all four of his number ones—and 13 of his

22 Grammy awards have been earned through rap/sung collaborations.

58

The

collaboration-driven fusion of pop and hip hop has been furthered still by hybrid

artists who both rap and sing, such as Drake, Mac Miller, Travis Scott, Young

Thug, and Nicki Minaj. Though Justin Bieber is not generally considered a hip-

hop artist, his 2020 album Changes is replete with soft-sounding trap beats atop

which his breathy vocals recall the sound world of Drake and his longtime

collaborator Noah “40” Shebib.

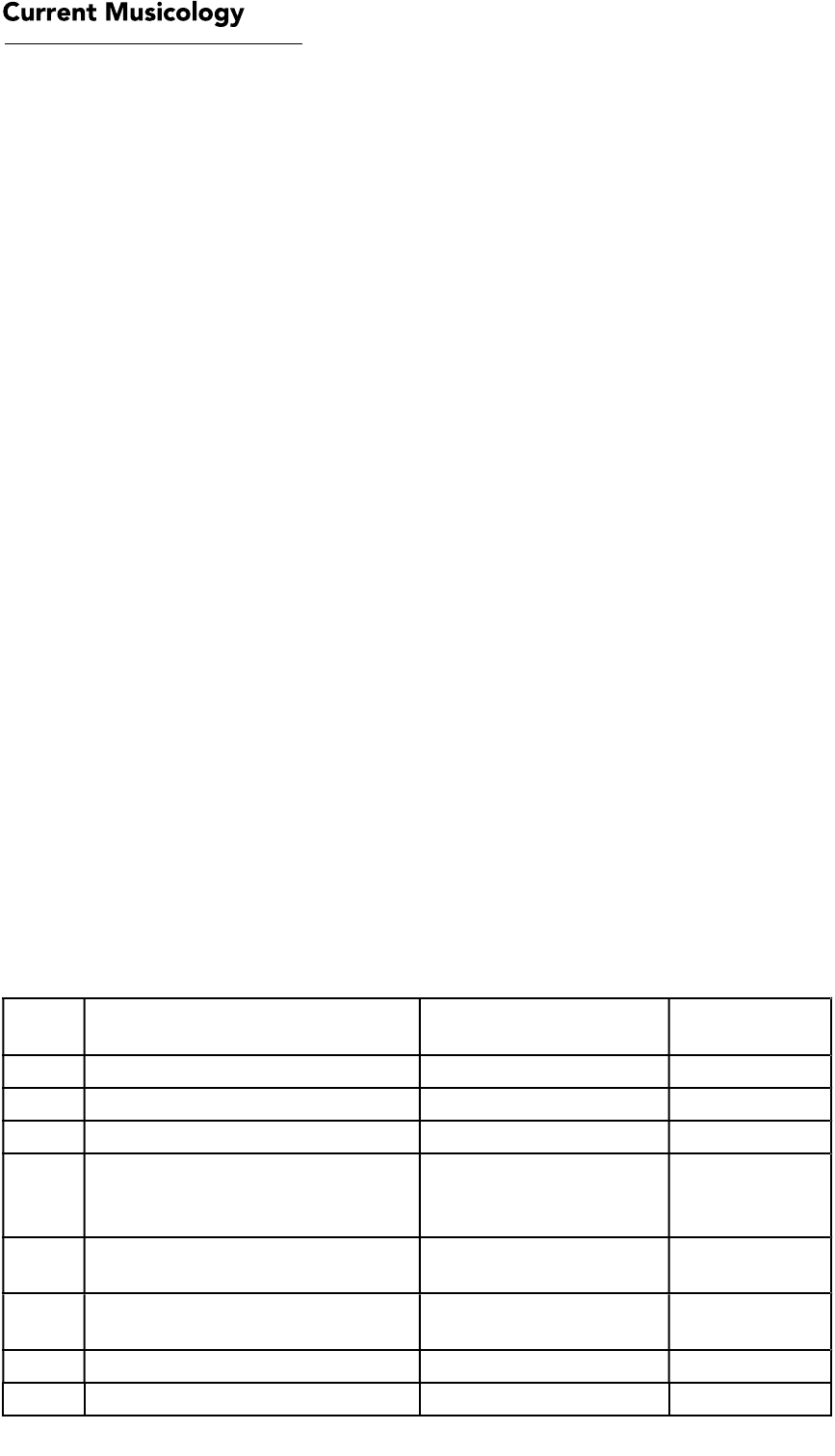

Formal Ordering and Balance

The final section of this paper investigates sectional ordering and balance in hip-

hop songs. Of the 123 corpus songs that were classified as verse-hook, 47%

featured a verse first, while 53% featured a hook first. This balance between

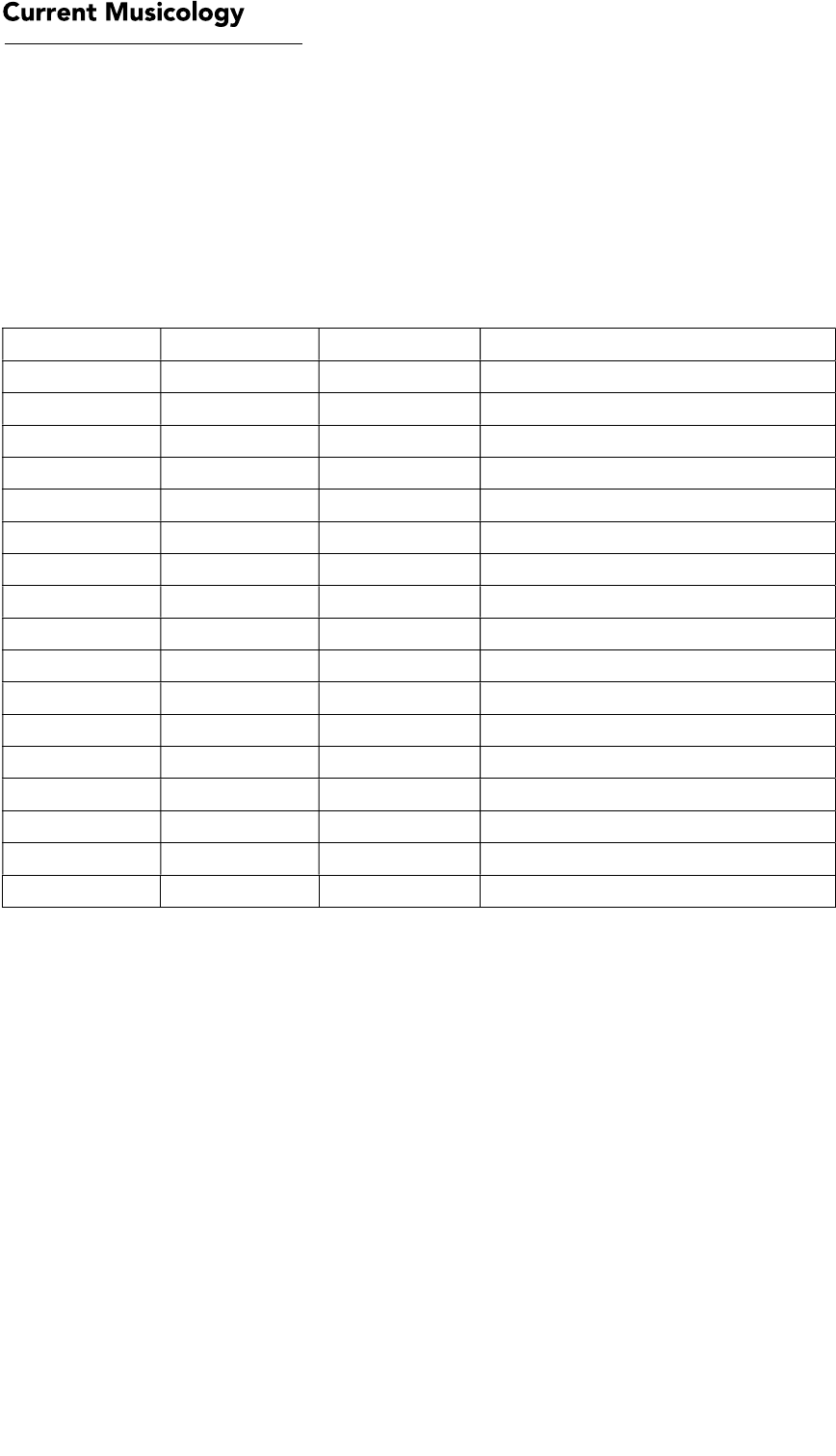

hook-first and verse-first songs becomes skewed when considered over time.

Example 10 plots all the verse-hook songs in the corpus in six time periods, each

selected for their relatively even distribution of songs (17 < n < 24 for each time

period).

59

While the 19 verse-hook songs released between 1982–1990 show a

relatively even balance of verse-initiating and hook-initiating forms, more recent

116

songs appear to favor a hook-first form. In fact, just one of the 19 verse-hook

songs released after 2011 had a verse appear before a hook.

Example 10: Leading section type in verse-hook songs. The time periods were selected to suit

two criteria. First, that all songs in a particular year would be included in the same period.

Second, that the periods be populated as evenly as possible, given the first criterion.

What do these observations tell us about the mainstreaming of hip-hop?

They suggest—again—that hip-hop song forms are evolving to gradually

foreground the hook at the expense of the verse. The significance of formal

ordering can be examined through music consumption patterns and habits.

Hubert Léveillé Gauvin’s 2018 study on musical form and the theory of attention

economy tested several hypotheses on a corpus of popular songs released

between 1986 and 2015. For each song, he determined how much time passed

before the first vocal entry, and before the first mention of the title lyrics. His

hypothesis was that, due to the way music is consumed via streaming services

with seemingly infinite choice at listeners’ fingertips, recent songs have been

written in order to better immediately capture listeners’ attention.

60

The working

assumption here is that because of an abundance of choice, listeners are less likely

to listen to an entire song, instead switching songs after a limited amount of

time.

61

Léveillé Gauvin’s research showed that the average elapsed time before

first vocal entry and title lyric decreased by year, meaning these features are

1982–1990 1991–1997 1998–2003 2004–2007 2008–2011 2012–2017

Verse First

58% 89% 52% 28% 26% 5%

Hook First

42% 11% 48% 72% 74% 95%

N =

19 19 21 18 23 19

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Leading Section Type in Verse-Hook Songs

Verse First Hook First

117

heard, on average, sooner, in more recent charting pop music. Assuming that

hip-hop hooks normally feature title lyrics, we can apply Léveillé Gauvin’s

hypothesis to a determination of how soon hook sections appear in hip-hop

songs.

62

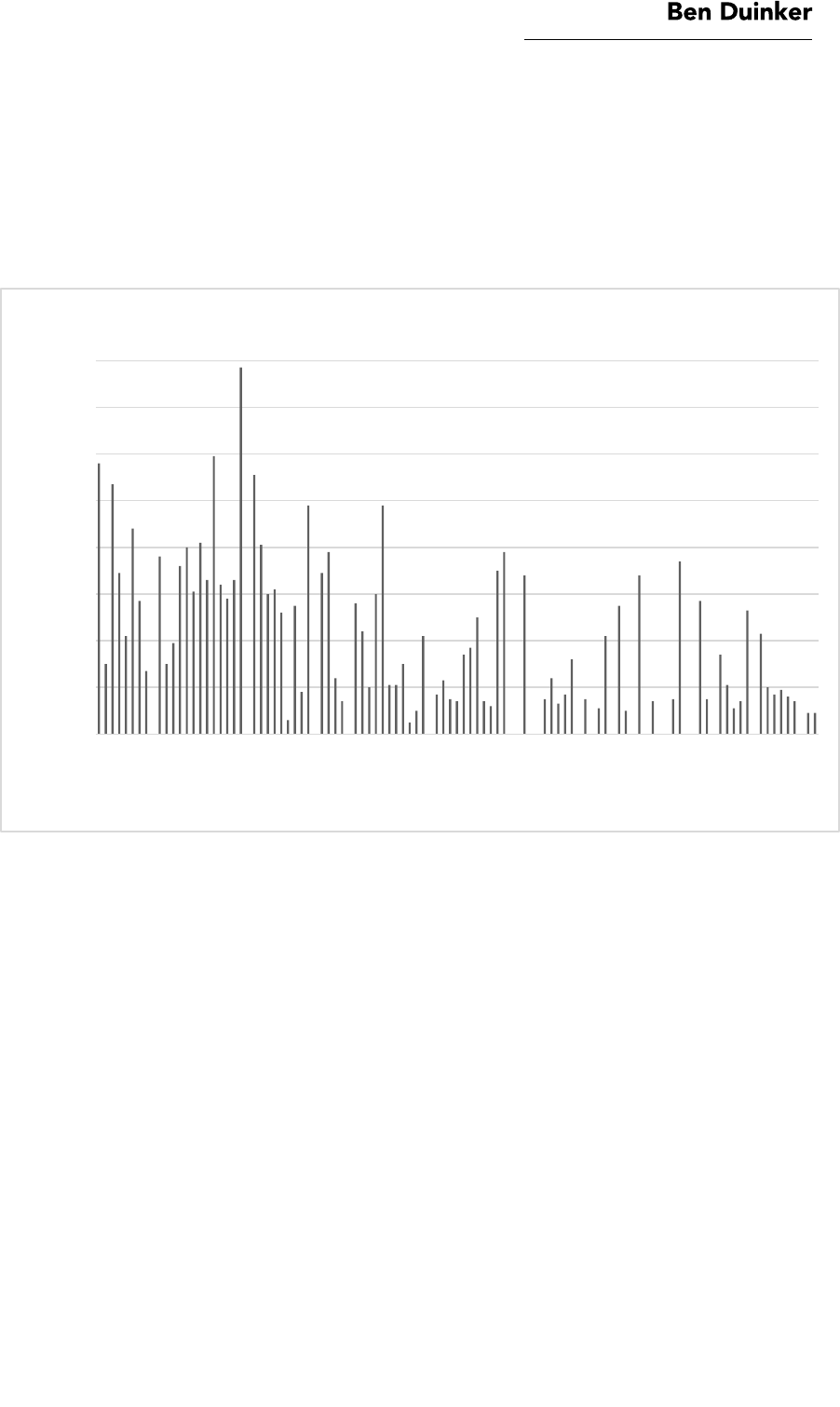

Example 11 plots this statistic over time, and the results here echo

Léveillé Gauvin’s findings: hook sections generally appear sooner in recent songs

than they do in older songs.

Example 11: Elapsed time until the arrival of the first hook section in 122 songs identified as

verse-hook in the corpus.

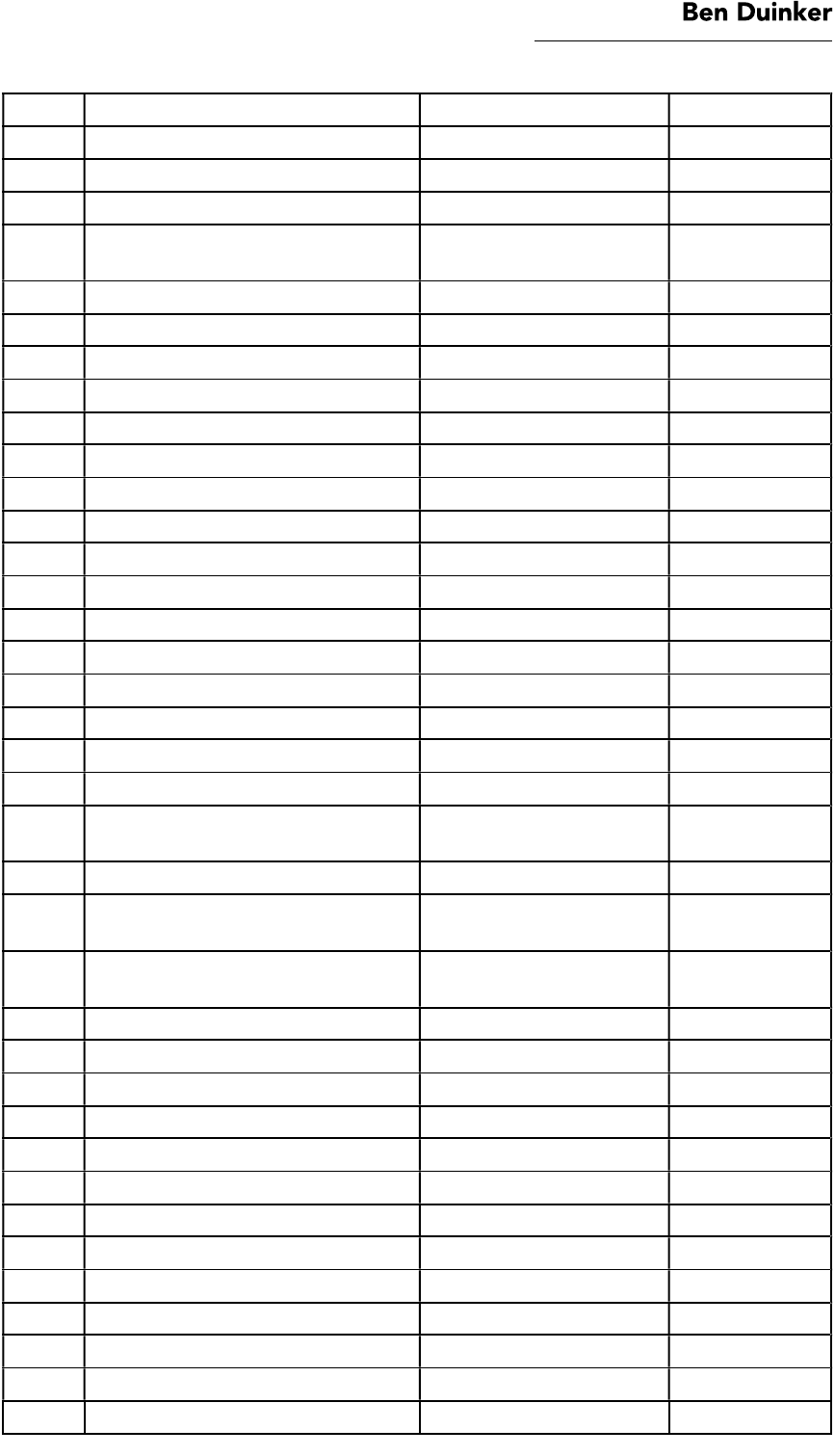

We can also observe the hook’s rising importance by measuring how

much of a song’s total duration they occupy. Example 12a plots total song

duration in seconds for all songs in the corpus. As can be seen, apart from

several long-duration outliers in the years prior to 1990, most songs tend to fall

in a bandwidth of 3:00 (180 s) to 5:30 (330 s) for duration; this has not changed

substantially over time. This observation is important to consider in light of

Example 12b, which plots the proportion of total song duration taken up by

hooks. The trendline here shows that the durational percentage of hooks is

steadily rising. The charts featured in Examples 10–12 demonstrate that hooks

are both arriving sooner and occupying an increasingly large share of the song’s

duration.

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

1982

1988

1990

1990

1992

1994

1995

1998

1999

2000

2002

2002

2003

2005

2005

2006

2007

2008

2008

2009

2010

2011

2011

2012

2014

2015

2016

Elapsed Time (s)

Song Release Year

Time Until First Hook

118

Example 12a: Song duration in seconds for all 160 songs in the corpus.

Example 12b: Proportion of song duration filled by hooks for all 160 songs in the corpus.

150

200

250

300

350

400

450

500

550

600

1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020

Song Duration (s)

Release Year

Song Duration

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020

Release Year

Proportion of Total Song Duration as Hooks

119

Conclusion

Song form is a musical parameter from which much can be learned about genre

and style, performance practice, and in a broader sense, genre crossover. Since

formal terminology is often used without being contextually defined, it becomes

easy to forget how this terminology has been shaped by style, performance

practice, and commerciality, and how it shapes our own reifying discourse of

genre.

In the first section of this paper, I identified four section types in recorded

hip hop, partly to invite further research on this topic, but also to foreground the

subtle characteristics that distinguish hip hop’s formal sections from those in

other genres of popular music. I believe this foregrounding to be important

because it calls attention to the pitfalls of defining formal features in hip hop

using a terminology that has already been heavily theorized for rock/pop music.

By using the term “chorus” to define hooks in hip hop, for example, we risk

casting these sections in the image of popular music, which, at least initially, bore

little influence over the formal construction of hip-hop music. A more

appropriate argument—albeit one I have not taken here—would be that what

once constituted a hook section in early hip hop has evolved into a pop-worthy

chorus section in more recent rap-sung collaborations.

63

With these discussions of section types established, I then investigated

how section types form complete songs. While verse-hook songs appear to be

the most common formal paradigm in hip-hop music, they were not common

in hip hop’s earliest years, when long-verse and strophic songs were more

prevalent. I stressed that long-verse and strophic forms appear closely related to

oral traditions of African American culture commonly cited as predecessors to

hip-hop music in general and rapping in particular. Toasts—long, epic poems

common in twentieth-century Black American culture—were often performed

in a manner similar to rapping (albeit more rhythmically free), complete with

rhyming couplets and phrases of similar length. The lyrical organization of toasts

foreshadowed the hip-hop verse: their performances essentially involved proto-

rapping, and their forms gave rise to the long-verse form in recorded hip hop. In

a similar vein, strophic songs and posse cuts can be understood as a reflection of

the cypher, a perennial locus of energy in collaborative and combative rapping.

Finally, I have argued that the mainstreaming of hip-hop music can be

seen (among other ways) through a gradual shift in formal focus from the verse

to the hook. Hooks first became more prevalent through the emergence of the

verse-hook paradigm and their profile was further raised through guest sung

120

vocals by established pop stars. Their leading position in songs’ formal sequences

has also increased their importance, with more and more songs presenting the

hook section earlier in the song (and occasionally right at the beginning). By

focusing on hook sections, I risk overstating their role in the mainstreaming

process and assuming a defined generic boundary exists between hip-hop and

pop music where one simply does not exist. Indeed, merely invoking the term

“crossover” implies that there is some border that a song, album, artist, or

musical community traverses.

64

In reality, the threshold between hip hop and

pop is porous and incompletely defined, perhaps more so today than ever before.

But this permeable boundary between hip hop and pop is precisely what makes

the hook—a section type that pervades nearly all pop music in some way or

another—so appealing as an agent of mainstreaming in hip hop. Just like

Temperley’s observation that choruses slowly became standard in 1960s

rock/pop music, hooks have slowly but surely infiltrated hip-hop music—a genre

that once had very few of them, and now hardly exists without them.

A sense of irony can be gleaned, then, from the lyrics at the end of each

verse of “Morris” (2014) by the Raleigh-based MC/producer Mez. Mez finishes

each verse with the refrain lyrics: “Not too many know Morris [x2] / those that

do know here be him and say that he needs a grave and a florist, chorus.” The

lyric “chorus” appears almost as an afterthought; the rhyme couplet “Morris /

florist” has already been realized, and “chorus” arrives on the final off-beat of the

measure. Following this utterance, a sparse instrumental section emerges—

certainly not a hook (or chorus for that matter). In fact, the texture in this

instrumental is sparser than the verse texture.

65

In this light, Mez’s signaling of a

chorus, however passing, invokes the expectation that one might occur—an

expectation conditioned through the increasing prevalence of hook sections in

hip hop—and also questions the very definition of “chorus” in hip-hop music.

Mez thus reminds us that section types are fluid, constantly evolving, and unique

in each musical genre in which they participate. Section types function as a venue

in which we can view the tension between the musical mainstream and genres—

like hip hop—that have historically been peripheral to this mainstream, yet are

now quite thoroughly a part of it.

121

Notes

1

Thompson writes “all the Black kids in Philadelphia who were listening to the radio that day

have the same story. It [the song] stopped us in our tracks” (2013, 23).

2

Temperley (2018) suggests that since the 1960s, the verse-chorus paradigm has supplanted

strophic form (similar to his simple verse and AABA forms) as the standard song form

preferred in rock music.

3

Jenkins (2017) provides numerous examples of the inter-generic bleed between mainstream

pop, hip hop, country, EDM, and other genres.

4

Kajikawa: “Like professional sports, rap is a cultural arena in which the most prominent actors

are black even though the majority of its spectators are not” (2015, 9). Chang: “The Black Thing

you once couldn’t understand became the ‘G’ Thang you could buy into” (2005, 420–21).

5

By using tight as the operative criterion, I follow Caplin’s notion of tight-knit and loose-knit

ideas (1998, 17).

6

Writings by Stephenson (2002), Covach (2004), Everett (2008), and de Clercq (2012)

enumerate types of song sections, their possible orderings, and formal paradigms that arise

from these orderings, but the repertoire these scholars focus upon is primarily what is broadly

classified as the poorly-defined genre of pop/rock (Biamonte 2017 makes special effort to

define pop/rock as “the constellation of genres and styles that has arisen around Anglophone

pop and rock music in the latter half of the twentieth century, including rhythm and blues and

heavy metal as well as genres with ‘pop’ or ‘rock’ in their names, but not country, hip-hop,

industrial, or electronic dance music” (89)). Quite often, corpus-driven studies that are

dedicated to analyzing song form—such as Summach (2012), de Clercq (2012), and Ensign

(2015)—use music that appeared on the Billboard Hot 100 or a similarly general-scope chart.

Especially before the mid 1990s, but also to some degree more recently, hip-hop music has

been underrepresented on these general-scope charts, and as such has not garnered close

attention in corpus studies on form. For his part, Summach acknowledges this gap, writing

that “Walser 1995, Krims 2000, Manabe 2006, and Butler 2006, for example, all describe formal

procedures in rap and electronic dance music that differ substantially from those that prevail

in pre-1990s Top-20 music. Further study would clarify the extent to which the absorption of

rap and dance into the mainstream after 1992 was eased by, or led to, hybridized formal

conventions” (2012, 14).

7

Summach’s corpus study involved Billboard-charting songs released up until 1989, meaning

he almost certainly would not have encountered hip-hop music. While Ensign’s study focused

on charting songs after 1989, he encountered more hip-hop music, yet still only comprising a

small portion of his total corpus (he does not specify how much).

8

Barna (2020) highlights this fact in her discussion of the “dance chorus”; a section type

developed in EDM, though now frequently incorporated in mainstream pop music.

122

9

Peres’s dissertation (2016) focuses on how recording production techniques contribute to the

proliferation of rhythmic, timbral, and textural elements as drivers of song form in recent pop

music.

10

Doll’s theoretical framework is predicated on the listening experience, so he chooses to

describe harmony in terms of the effects it creates to the ear, rather than conceiving of harmony

in terms of “harmonic objects” (2017, 9).

11

While this point may appear to undermine the utility of using these four section types to

classify song forms, as I do here, instrumental and loose-vocal sections are rarely the chief

determinant of a song’s formal type. There are only a handful of songs in my corpus where

instrumental sections might be interpreted to express hook-like qualities and thus change the

definition of the song’s formal type. Of the 24 songs identified as strophic in the corpus, no

more than five or so—to my ear—present instrumental sections that are staunchly hook-like;

“Mind Playing Tricks on Me” (Geto Boys, 1991) represents one possible candidate, where the

instrumental sections between each verse feature a guitar riff that expresses a hook-like

aesthetic.

12

I define measures in hip-hop music by the near-ubiquitous underlying backbeat pattern of

the drums in the song’s beat layer. That is to say, one measure equals one iteration of a 4/4

backbeat pattern. By contrast, de Clercq (2016) defends the practice of determining measure

length, and by extension song tempo, using absolute time as a determinant, citing perceptual

studies that have shown a two-second timespan to be the ideal duration for experiential

measures in subjects listening to popular songs. While de Clercq’s findings are compelling, two

factors led me to part from them in my approach. First, his chosen repertoire is pop and rock

music. In general, these styles contain much more variance in phrase length of vocal lines,

harmonic rhythm of accompaniment, and rhythmic variation of drum patterns than is found

in hip-hop music. Second, the perceptual studies de Clercq cites mainly focus on tapping

experiments. I posit that a more reliable indicator of tempo and measure perception would

include a more embodied response to the aural stimuli, such as dancing. While I know of no

studies that do this with respect to hip-hop music, I hypothesize that the results would show a

more faithful correspondence to backbeat patterns as determinants of tempo and measure.

13

Duinker (2021) unpacks rhyme structure in hip-hop flow in detail, relating it to phrase length

and ultimately metric structure in hip-hop music. Central to this discussion is the assumption

that rhymes typically occur at the end of measures and function as phrase-ending devices.

14

See Berry 2018, 3. Duinker (2021) describes the variance in loop length in hip-hop beats,

providing examples of 2-, 4-, and 8-measure beat loops.

15

I use the term “allegedly” here because I can locate no concrete support for this claim beyond

what has been written on online blogs and genius.com, a user-annotated lyrics site. It is clear,

however, from listening to Shanté’s original recording of “Roxanne’s Revenge,” that an element

of spontaneity obtains, notably through her abnormal and often unpredictable breathing

patterns. This observation lends support to the claim that “Roxanne’s Revenge” was recorded

in a single take, with no prior planning on breathing points.

16

In an interview with the website Complex (Cho 2011), DJ Premier, the producer of “NY State

of Mind,” describes how Nas wrote his lyrics for the song in-studio and recorded them in a

123

single take, without having worked out his flow rhythms aloud prior to recording. Premier

notes especially Nas’s utterance at the beginning of the track “I don’t know how to start this

shit” as evidence of the spontaneity in this recording session.

17

I interpret this song as containing two hooks by virtue of the length of repeated lyrics

comprising the double-hook section (longer than is typical in hip-hop music), and the textural

shift that occurs partway through these lyrics (which to my ear denotes a sectional break).

18

Many of Public Enemy’s hook lyrics fit this description, notably “Bring the Noise” (It Takes

a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, 1988), and “Fight the Power” (Fear of a Black Planet,

1990).

19

Current and recently active MCs such as Drake, Young Thug, Mac Miller, and Chance the

Rapper have extensively used singing (usually autotuned) in verses.

20

Berry (2018) and Edwards (2009) use the terms hook and chorus interchangeably, while most

other authors use one term or the other with no explanation.

21

These repeated lyrics are quite often repeated iterations of a refrain that concluded the

previous verse. In contrast to Temperley’s approach for rock music (2018, 153–154), I allow

for refrain lyrics to be part of the verse or hook, depending on context.

22

Examples abound in hip-hop music where the sections interspersing verses (be they hook or

instrumental sections) are less texturally dense than the verses. Several recent examples include

“Norf Norf” (Vince Staples, 2015), “Morris” (King Mez, 2014), “Talk About It” (Dr. Dre ft.

King Mez, 2015), and “Panda” (Desiigner, 2016).

23