Trends in Higher Education Series

Education Pays 2019

THE BENEFITS OF HIGHER EDUCATION FOR INDIVIDUALS AND SOCIETY

Jennifer Ma, Matea Pender, and Meredith Welch

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Jennifer Ma

Senior Policy Research Scientist, College Board

Matea Pender

Policy Research Scientist, College Board

Meredith Welch

Doctoral Student, Policy Analysis & Management, Cornell University

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Anthony LaRosa and Edward Lu provided critical support for this publication. We also beneted from comments

from Dean Bentley, Jessica Howell, Michael Hurwitz, and Melanie Storey. Sandy Alexander provided expert

graphic design work. The publication would not have been possible without the cooperation and support of many

individuals at College Board, including Connie Betterton, Auditi Chakravarty, Jennifer Hwang, Jennifer Ip, Karen

Lanning, George Lalis, Robert Majoros, Jose Rios, and Jennifer San Miguel.

The tables supporting all of the graphs in this report, a PDF version of the report, and a PowerPoint le containing

individual slides for all of the graphs are available on our website research.collegeboard.org/research.

Please feel free to cite or reproduce the data in this report for noncommercial purposes with proper attribution.

For inquiries or requesting hard copies, please contact: trends@collegeboard.org.

© 2019 College Board. College Board, Advanced Placement Program, SAT, and the acorn logo are registered

trademarks of the College Board. All other products and services may be trademarks of their respective owners.

Trends in Higher Education Series

Education Pays 2019

THE BENEFITS OF HIGHER EDUCATION FOR INDIVIDUALS AND SOCIETY

Jennifer Ma, Matea Pender, and Meredith Welch

With an Introduction by Jessica Howell

4

Highlights

As in previous editions, Education Pays 2019: The Benets of Higher

Education for Individuals and Society documents dierences in the

earnings and employment patterns of U.S. adults with dierent levels

of education. It also compares health-related behaviors, reliance on

public assistance programs, civic participation, and indicators of the

well-being of the next generation.

In addition to reporting median earnings by education level, this

year’s report presents data on variation in earnings by dierent

characteristics such as gender, race/ethnicity, occupation, college

major, and sector. Education Pays 2019 also examines the persistent

disparities across dierent socioeconomic groups in college

participation and completion.

We present correlations between various outcomes and educational

attainment. It is worth noting that not all of the observed dierences

in outcomes are attributable to education. However, reliable

statistical analyses support the signicant role of postsecondary

education in generating the benets reported and we cite causal

evidence when possible.

PARTICIPATION AND SUCCESS

IN HIGHER EDUCATION

Although college enrollment rates continue to rise, gaps

in enrollment rates persist across demographic groups.

In 1998, 59% of black and 55% of Hispanic recent high school

graduates enrolled in college within one year of high school

graduation, compared with 68% of white students. In 2018,

enrollment rates were 60%, 66%, and 70% for black, Hispanic,

and white students, respectively. (Figure 1.1A)

Since 1989, the enrollment rate for recent female high school

graduates has consistently exceeded that of their male

counterparts. Annual enrollment rates uctuate, but the average

gender gap increased from 4 percentage points between 1988

and 1998 to 5 percentage points the following decade and

7 percentage points between 2008 and 2018. (Figure 1.2A)

Among students with similar high school math test scores,

college enrollment rates are higher for those from higher

socioeconomic status (SES) quintiles than for those from

lower SES quintiles. (Figure 1.3A)

While overall educational attainment is increasing, college

completion rates and attainment patterns dier considerably

across demographic groups.

The percentage of young adults in the U.S. between the ages

of 25 and 34 with at least a bachelor’s degree grew from 11% in

1960 to 24% in 1980 and 1990. In 2018, 39% of adults in this age

group had earned at least a bachelor’s degree. (Figure 1.5A)

In 1998, the percentage of female adults age 25 to 29 who had

completed at least a bachelor’s degree was 17%, 11%, and 34%

for blacks, Hispanics, and whites, respectively. By 2018, these

percentages had increased to 25%, 22%, and 47%. (Figure 1.6)

In 1998, the percentage of male adults age 25 to 29 who had

completed at least a bachelor’s degree was 13%, 10%, and 31%

for blacks, Hispanics, and whites, respectively. By 2018, these

percentages had increased to 20%, 17%, and 39%. (Figure 1.6)

Within each sector, students with higher family incomes were

more likely to complete a degree than their lower-income peers

with similar high school GPAs. (Figure 1.4)

Participation in postsecondary education diers

considerably across states.

The percentage of 18- to 24-year-olds enrolled in college in

2017 ranged from 29% in Alaska and 31% in Nevada to 56% in

the District of Columbia and 57% in Rhode Island. (Figure 1.7)

In 2017, the percentage of adults age 25 and older with at least a

bachelor’s degree ranged from 20% in West Virginia and 22% in

Mississippi to 44% in Massachusetts and 57% in the District of

Columbia. (Figure 1.7)

THE BENEFITS OF HIGHER EDUCATION

AND VARIATION IN OUTCOMES

Individuals with higher levels of education earn more, pay

more taxes, and are more likely than others to be employed.

In 2018, the median earnings of bachelor’s degree recipients

with no advanced degree working full time were $24,900

higher than those of high school graduates. Bachelor’s degree

recipients paid an estimated $7,100 more in taxes and took

home $17,800 more in after-tax income than high school

graduates. (Figure 2.1)

The typical 4-year college graduate who enrolls at age 18 and

graduates in 4 years can expect to earn enough relative to a high

school graduate by age 33 to compensate for being out of the

labor force for 4 years and for borrowing the full tuition and fees

and books and supplies without any grant aid. (Figure 2.2A)

In 2018, among full-time year-round workers between the ages

of 25 and 34, median earnings among women with at least a

bachelor’s degree were $52,500, compared with $29,800 for

those with a high school diploma. Median earnings among men

with at least a bachelor’s degree were $63,300, compared with

$39,800 for those with a high school diploma. (Figure 2.6)

In 2018, among adults between the ages of 25 and 64, 69% of

high school graduates, 73% of those with some college but no

degree, 78% of those with associate degrees, and 83% of those

with 4-year college degree were employed. (Figure 2.11)

The unemployment rate for individuals age 25 and older with at

least a bachelor’s degree has consistently been about half of

the unemployment rate for high school graduates. (Figure 2.12A)

In 2018, the unemployment rate for 25- to 34-year-olds with at

least a bachelor’s degree was 2.2%, compared with 5.7% among

high school graduates. (Figure 2.12B)

5

Median earnings increase with level of education, but there

is considerable variation in earnings at each level of

educational attainment.

The percentage of full-time year-round workers age 35 to 44

earning $100,000 or more in 2018 ranged from 2% of those

without a high school diploma and 5% of high school graduates

to 28% of those whose highest attainment was a bachelor’s

degree and 43% of advanced degree holders. (Figure 2.3)

Between 2016 and 2018, median earnings of individuals age 25 to

34 working full time year-round with a bachelor’s degree ranged

from $42,100 among black females and $43,900 among Hispanic

females to $72,300 among Asian males. The earnings premium

for a bachelor’s degree relative to a high school diploma was the

highest among Asian males and females. (Figure 2.4)

In 2018, median earnings of female 4-year college graduates

working full time year-round were $56,700. However, 25% of

them earned less than $40,500, and another 25% earned more

than $81,600. (Figure 2.5)

In 2018, median earnings of male 4-year college graduates

working full time year-round were $75,200. However, 25% of

them earned less than $50,400, and 25% earned more than

$110,000. (Figure 2.5)

Between 2013 and 2017, among occupations that employ large

numbers of both high school graduates and college graduates,

the median earnings of those with only a high school diploma

ranged from $31,400 (in 2017 dollars) for retail salespersons

to $60,100 for general and operations managers. The median

earnings of those with at least a bachelor’s degree ranged from

$41,800 (in 2017 dollars) for administrative assistants to $89,500

for rst-line supervisors of nonretail workers. (Figure 2.8)

In 2016 and 2017, median earnings for early career bachelor’s

degree recipients ranged from $32,100 a year for early childhood

education majors to $62,000 for computer science majors. For

those in mid-career, median earnings ranged from $41,000 to

$95,000. (Figure 2.9)

Institutional median earnings vary by sector. From 2014 to 2015,

the typical 4-year college’s median earnings of 2003-04 and

2004-05 federal student aid recipients ranged from $34,600 at

for-prot institutions to $42,800 at private nonprot institutions

and $42,950 at public institutions. (Figure 2.10A)

College education increases the chance that adults will move up

the socioeconomic ladder and reduces the chance that adults

will rely on public assistance.

Among those who attended the most selective colleges, 68% of

children from the lowest parent income quintile were in the top

two income quintiles as adults, compared with 72% of children

from the middle-income quintile and 76% from the highest income

quintile. (Figure 2.15A)

Children from lower-income backgrounds were less likely to attend

more selective institutions. Children whose parents were in the

top 1% of the income distribution were nearly 50 times more likely

to attend the most selective institutions as those whose parents

were in the bottom 20%. (Figure 2.15B)

In 2018, 4% of bachelor’s degree recipients age 25 and older

lived in poverty, compared with 13% of high school graduates.

(Figure 2.16A)

In 2018, 7% of individuals age 25 and older with associate

degrees and 9% of those with some college but no degree lived

in households that beneted from the Supplemental Nutrition

Assistance Program (SNAP), compared with 12% of those with

only a high school diploma. (Figure 2.17)

Having a college degree is associated with a healthier lifestyle,

potentially reducing health care costs. Adults with higher levels

of education are more active citizens than others and are more

involved in their children’s activities.

In 2018, 69% of 25- to 34-year-olds with at least a bachelor’s

degree and 47% of high school graduates reported exercising

vigorously at least once a week. (Figure 2.19A)

Children of parents with higher levels of educational attainment

are more likely than other children to engage in a variety of

educational activities with their family members. (Figures 2.20B

and 2.21A)

Among adults age 25 and older, 19% of those with a high school

diploma volunteered in 2017, compared with 42% of those with

a bachelor’s degree and 52% of those with an advanced degree.

(Figure 2.22A)

Voting rates are higher among individuals with higher levels

of education. In the 2016 presidential election, 73% of 25- to

44-year-old U.S. citizens with at least a bachelor’s degree voted,

compared with 41% of high school graduates in the same age

group. (Figure 2.23A)

Contents

4

Highlights

8

Introduction

Part 1: The Distribution of Benets: Who Participates and Succeeds in Higher Education

College Enrollment

10

College Enrollment by Race/

Ethnicity

FIGURE 1.1A

College Enrollment Rates of Recent High School Graduates by Race/Ethnicity over Time

FIGURE 1.1B

College Enrollment Rates of 18- to 24-Year-Olds by Race/Ethnicity over Time

11

College Enrollment by Gender FIGURE 1.2A

College Enrollment Rates of Recent High School Graduates by Gender over Time

FIGURE 1.2B

College Enrollment Rates of 18- to 24-Year-Olds by Gender over Time

12

College Enrollment by Math

Score and Socioeconomic

Status

FIGURE 1.3A

College Enrollment by Math Quintile and Parents’ Socioeconomic Status

FIGURE 1.3B

Sector of First Postsecondary Institution by Math Quintile and Parents’ Socioeconomic Status

College Completion and Educational Attainment

13

College Completion Rates FIGURE 1.4

Six-Year Completion Rates by Sector, High School GPA, and Family Income

14

Educational Attainment FIGURE 1.5A

Educational Attainment of Individuals Age 25 to 34 over Time

FIGURE 1.5B

Educational Attainment of Individuals by Age Group, 2018

15

Educational Attainment by

Race/Ethnicity and Gender

FIGURE 1.6

Percentage of 25- to 29-Year-Olds Who Have Completed High School or a Bachelor’s Degree,

by Race/Ethnicity and Gender over Time

16

College Enrollment and

Attainment by State

FIGURE 1.7

College Enrollment Rates of 18- to 24-Year-Olds and Educational Attainment by State

17

Education, Earnings, and Tax

Payments

FIGURE 2.1

Median Earnings and Tax Payments of Full-Time Year-Round Workers Age 25 and Older,

by Education Level, 2018

18

Earnings Premium Relative to

Price of Education

FIGURE 2.2A

Estimated Cumulative Full-Time Earnings Net of Loan Repayment for Tuition and Fees and

Books and Supplies, by Education Level

19

Earnings Premium Relative to

Price of Education: Alternative

Scenarios

FIGURE 2.2B

Age at Which Cumulative Earnings of College Graduates Exceed Those of High

School Graduates

20

Variation in Earnings Within

Levels of Education

FIGURE 2.3

Earnings Distribution of Full-Time Year-Round Workers Age 35 to 44, by Education Level, 2018

21

Earnings by Race/Ethnicity,

Gender and Education Level

FIGURE 2.4

Median Earnings of Full-Time Year-Round Workers Age 25 to 34, by Race/Ethnicity, Gender, and

Education Level, 2016–2018

22

Earnings by Gender and

Education Level

FIGURE 2.5

Median, 25th Percentile, and 75th Percentile Earnings of Full-Time Year-Round Workers Age 25

and Older, by Gender and Education Level, 2018

23

Earnings over Time by Gender

and Education Level

FIGURE 2.6

Median Earnings of Full-Time Year-Round Workers Age 25 to 34 over Time, by Gender and

Education Level

24

Earnings Paths FIGURE 2.7

Median Earnings of Full-Time Year-Round Workers, by Age and Education Level, 2013–2017

25

Earnings by Occupation and

Education Level

FIGURE 2.8

Median Earnings of Full-Time Workers Age 25 and Older with a High School Diploma and Those

with at Least a Bachelor’s Degree, by Occupation, 2013–2017

26

Earnings by College Major FIGURE 2.9

Median Earnings of Early Career and Mid-Career College Graduates Working Full Time,

by College Major, 2016−2017

27

Variation in Earnings by

Institutional Sector

FIGURE 2.10A

Distribution of 2014 and 2015 Institutional Median Earnings of Federal Student Aid Recipients

in 2003-04 and 2004-05, by Sector

FIGURE 2.10B

Average 2014 and 2015 Earnings of Dependent Federal Student Aid Recipients in 2003-04 and

2004-05, by Sector and Graduation Rate

Part 2: Individual and Societal Benets of Higher Education

Earnings

6

Contents—Continued

Other Economic Benets

28

Employment FIGURE 2.11

Civilian Population Age 25 to 64: Percentage Employed, Unemployed, and Not in Labor Force,

2008, 2013, and 2018

29

Unemployment FIGURE 2.12A

Unemployment Rates of Individuals Age 25 and Older, by Education Level, 1998 to 2018

30

Unemployment FIGURE 2.12B

Unemployment Rates of Individuals Age 25 and Older, by Age and Education Level, 2018

FIGURE 2.12C

Unemployment Rates of Individuals Age 25 and Older, by Race/Ethnicity and Education

Level, 2018

31

Retirement Plans FIGURE 2.13

Employer-Provided Retirement Plan Coverage Among Full-Time Year-Round Workers Age 25

and Older, by Sector and Education Level, 2018

32

Health Insurance FIGURE 2.14A

Employer-Provided Health Insurance Coverage Among Full-Time Year-Round Workers Age 25

and Older, by Education Level, 1998, 2008, and 2018

FIGURE 2.14B

Employer-Provided Health Insurance Coverage Among Part-Time Workers Age 25 and Older,

by Education Level, 1998, 2008, and 2018

33

Social Mobility FIGURE 2.15A

Percentage of Children in Top Income Quintiles as Adults, by Parents’ Income and College Tier:

Children Born in 1980 to 1982

FIGURE 2.15B

Distribution of College Enrollment by Parents’ Income Quintile, Children Born in 1980 to 1982

34

Poverty FIGURE 2.16A

Percentage of Individuals Age 25 and Older Living in Households in Poverty, by Household Type

and Education Level, 2018

FIGURE 2.16B

Living Arrangements of Children Under 18 Years of Age, by Poverty Status and Highest

Education of Either Parent, 2018

35

Public Assistance Programs FIGURE 2.17

Percentage of Individuals Age 25 and Older Living in Households That Participated in Various

Public Assistance Programs, by Education Level, 2018

Health Benets

36

Smoking FIGURE 2.18A

Smoking Rates Among Individuals Age 25 and Older over Time, by Education Level

FIGURE 2.18B

Smoking Rates Among Individuals Age 25 and Older, by Gender and Education Level, 2017

37

Exercise FIGURE 2.19A

Exercise Rates Among Individuals Age 25 and Older, by Age and Education Level, 2018

FIGURE 2.19B

Percentage Distribution of Leisure-Time Aerobic Activity Levels Among Individuals Age 25 and

Older, by Education Level, 2018

Other Individual and Societal Benets

38

Parents and Children:

Preschool-Age Children

FIGURE 2.20A

Percentage of 3- to 5-Year-Olds Enrolled in Preschool Programs, by Parents’ Education

Level, 2017

FIGURE 2.20B

Percentage of 3- to 5-Year-Olds Participating in Activities with a Family Member, by Parents’

Education Level, 2016

39

Parents and Children:

School-Age Children

FIGURE 2.21A

Percentage of Kindergartners Through Fifth Graders Participating in Activities with a Family

Member in the Past Month, by Parents’ Education Level, 2016

FIGURE 2.21B

Percentage of Elementary and Secondary School Children Whose Parents Were Involved in

School Activities, by Parents’ Education Level, 2016

40

Civic Involvement FIGURE 2.22A

Percentage of Individuals Age 25 and Older Who Volunteered, by Gender and Education

Level, 2017

FIGURE 2.22B

Percentage of Individuals Age 25 and Older Who Volunteered, by Age and Education

Level, 2017

41

Voting FIGURE 2.23A

Voting Rates Among U.S. Citizens, by Age and Education Level, 2016 and 2018

FIGURE 2.23B

Voting Rates Among U.S. Citizens During Presidential Elections over Time, by Education Level

42

References

7

8

Introduction

Jessica Howell

Vice President, Research, College Board

Education Pays: The Benets of Higher Education for Individuals

and Society documents the substantial individual payo from

investments in higher education, the variation in outcomes

experienced by dierent individuals, and the benets we all enjoy

from a more educated populace. Since 2004, College Board has

been publishing updates to this report every three years. Education

Pays rounds out the Trends in Higher Education series that includes

Trends in Student Aid and Trends in College Pricing. These reports

provide a foundation for evaluating public policies to increase

educational opportunities.

This report combines publicly available government statistics and

academic research to paint a detailed and integrated picture of the

benets of higher education and the distribution of those benets

across society. Many graphs in this report compare the experiences

of people with dierent education levels and illustrate straightforward

correlations between education and various outcomes. When

possible, we cite causal evidence of the direct impact of higher

education on both nancial outcomes and behavior patterns.

COLLEGE ACCESS AND SUCCESS

Education Pays provides information about college enrollment

patterns, completion rates, and educational attainment levels

across demographic groups in the United States. The nation has

made progress increasing the share of young adults who invest in

postsecondary education. The percentage of 18- to 24-year-olds

who enroll in college increased from 25% in 1978 to 41% in 2018

(Figure 1.1B). The growth in college enrollment over time translates

into 67% of adults age 25 to 34 in the U.S. having at least some

college experience in 2018, an increase from 57% in 2000 and from

46% in 1980 (Figure 1.5A).

Although the share of all young adults age 25 to 29 who had

a bachelor’s degree or higher rose to 36% in 2018, this share

ranged from 19% for Hispanics and 23% for blacks to 43% for

whites and 66% for Asians (Page 15). Gaps in college enrollment

and completion rates can be partially explained by dierences in

academic preparation in K–12. Yet, even among students with similar

academic achievement levels in high school, students from lower-

socioeconomic-status families enroll and graduate at lower rates

than those from higher-socioeconomic-status families (Figures

1.3A and 1.4). Moreover, there are stark dierences by student

socioeconomic status in types of postsecondary institutions

students with similar academic preparation choose, which likely

contributes to uneven college completion rates (Figure 1.3B).

THE PAYOFF OF HIGHER EDUCATION

FOR INDIVIDUALS

Most college students report improved job prospects and nancial

security as a primary reason for college attendance. The data are

clear: adults with postsecondary credentials are, in fact, more

likely to be employed and to earn more than individuals who did

not attend college. In 2018, 83% of adults with bachelor’s degrees

or higher were employed, compared with 69% of adults with a

high school diploma (Figure 2.11). In 2018, median earnings of

full-time workers with associate and bachelor’s degrees were

24% and 61% higher, respectively, than that of their peers with

only a high school diploma. The earnings premium for workers

with postbaccalaureate credentials is even higher (Figure 2.1).

Though not all the earnings premia cited above are attributable to

dierences in educational attainment, a growing body of research

clearly identies postsecondary education as causally impacting

earnings (Zimmerman, 2014; Hoekstra, 2009).

The benets of a college education extend beyond nancial

gains. More educated citizens have greater access to health care

and retirement plans. They are more likely to engage in healthy

behaviors, be active and engaged citizens, and be in a position to

provide better opportunities for their children.

Because the price of college continues to rise over time, even

substantial benets from investing in education must be compared

with costs in order to assess whether college is a worthwhile

investment. Figures 2.2A and 2.2B indicate that a 4-year college

graduate who enrolls at age 18 with median earnings can expect

to earn enough by age 33 to compensate for being out of the labor

force for four years and for borrowing the full tuition and fees and

books and supplies without any grant aid. An associate degree is

both faster and less expensive to acquire but yields smaller earnings,

on average, than a bachelor’s degree, so it is unsurprising that the

break-even age of an associate degree is similar (age 31). Over the

course of a lifetime, and accounting for the costs of obtaining a

degree, individuals with a bachelor’s degree earn about $400,000

more than individuals with a high school degree. The nancial

benets of an associate degree are roughly half as large.

The average payo to college is considerable, but not all students

reap the same nancial rewards. Several analyses in this report

focus on the variation in the outcomes of higher education

across and within demographic groups, types of credentials, and

institutional sectors. The distribution of earnings in Figure 2.3 tells

a more nuanced story about the mid-career earnings of full-time

workers with the same level of education. While 28% of employed

adults with a bachelor’s degree working full time earn more than

9

$100,000, 17% earn less than $40,000. This disparity in earnings

outcomes reects, among other underlying factors, geographic

dierences in wages, variation in types of colleges attended, and

dierences in elds of study and occupations (Figures 2.8 through

2.10B). Although these nuances are important to our understanding

of the circumstances under which educational investments pay o,

the overall patterns are clear—more education is associated with

increased opportunities for the vast majority of students.

This report also reveals earnings dierentials among individuals with

similar levels of education by race and gender. Underrepresented

minorities continue to earn less than their white and Asian

counterparts and females continue to earn less than their male

counterparts (Figures 2.4 through 2.6). Though issues of equity exist

in the workplace, postsecondary education remains a catalyst for

social mobility. Figure 2.15A shows that a college education can be

a powerful equalizer. When students attend similar postsecondary

institutions, the percentage of students who end up in the top two

income quintiles as adults is nearly the same for students from the

lowest-income-quintile families as it is for those from top-income-

quintile families. Although Figure 2.15B illustrates that auent

students are still considerably more likely to attend selective colleges

than their less auent peers, expanding access to selective

colleges remains a promising avenue to economic mobility.

THE PUBLIC BENEFITS OF HIGHER EDUCATION

Society at large also gains from increases in postsecondary

attainment. A more productive economy generates a higher standard

of living. We can all enjoy the benets of having a more well-educated

populace. Increases in wages generate higher tax payments at the

local, state, and federal levels. In 2018, four-year college graduates

paid, on average, 82% more in taxes than high school graduates and,

for those with a professional degree, average tax payments were

more than three times as high as those of high school graduates.

Spending on social support programs such as unemployment

compensation, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program

(SNAP), and Medicaid is much lower for individuals with higher levels

of education. Figure 2.17 shows that SNAP participation among

individuals with a high school diploma is four times as high as that

among those with a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Education is associated with healthful behaviors and civic

engagement. Over time, rates of smoking have dropped the most

precipitously among college-educated adults (Figure 2.18A). Rates

of reported exercise rise with educational attainment for individuals

of all ages (Figure 2.19A). Adults with greater educational attainment

are more likely to volunteer and to vote. In the 2016 presidential

election, 73% of young adults age 25 to 44 with at least a bachelor’s

degree voted, compared with 41% of their peers with a high school

diploma (Figure 2.23A).

The data in Education Pays provide a strong argument for increasing

access to and support for successful postsecondary pathways.

Research suggests that increased public commitment to this priority

through public subsidies for higher education institutions is the most

promising approach to increasing degree completion and realizing

greater private and public benets (Deming & Walters, 2017; Avery,

Howell, Pender, & Sacerdote, 2019).

IS COLLEGE WORTH IT?

A postsecondary education opens the door to many opportunities.

As the price of college continues to rise, more students and families

are asking if college is worth it. Media headlines highlight stories

of college students saddled with debt without gainful employment.

Although these stories do exist, they are far from typical. As

illustrated in this report, college is a worthwhile investment that pays

o over time for most students. Of course, students and families

face crucial choices—which institution, which eld of study, and

how to nance it all—that factor into their eventual answer to the

question, “Was college worth it?” Additional data and transparency

about the costs and benets of postsecondary education are

needed to inform these choices.

Education Pays shows the variation in earnings by institutional

sector based on the college-level earnings data from the

Department of Education’s College Scorecard (Figures 2.10A and

2.10B). In 2019, the Department of Education expanded upon the

college-level earnings data it began releasing in 2015. It provided

program-level data for every college, including median debt data and

median rst-year earnings data. This is the rst time such detailed

data about labor market outcomes of students from specic majors

and colleges have been made available at the national level. The

earnings data include information for associate and bachelor’s

degrees, certicate programs, and graduate degrees—a substantial

step toward transparency around the monetary benets of specic

postsecondary investments. Continued progress in providing data

on the benets and costs of postsecondary investments at the

institution and program levels will give students, families, institutions,

and policymakers the information they need to quantitatively

evaluate which postsecondary opportunities best serve individual

and public educational goals.

10

EDUCATION PAYS 2019 Part 1: Distribution of Benets

College Enrollment by Race/Ethnicity

In 1998, 59% of black and 55% of Hispanic recent high school graduates enrolled in college

within one year of high school graduation, compared with 68% of white students. In 2018,

enrollment rates were 60%, 66%, and 70% for black, Hispanic, and white students, respectively.

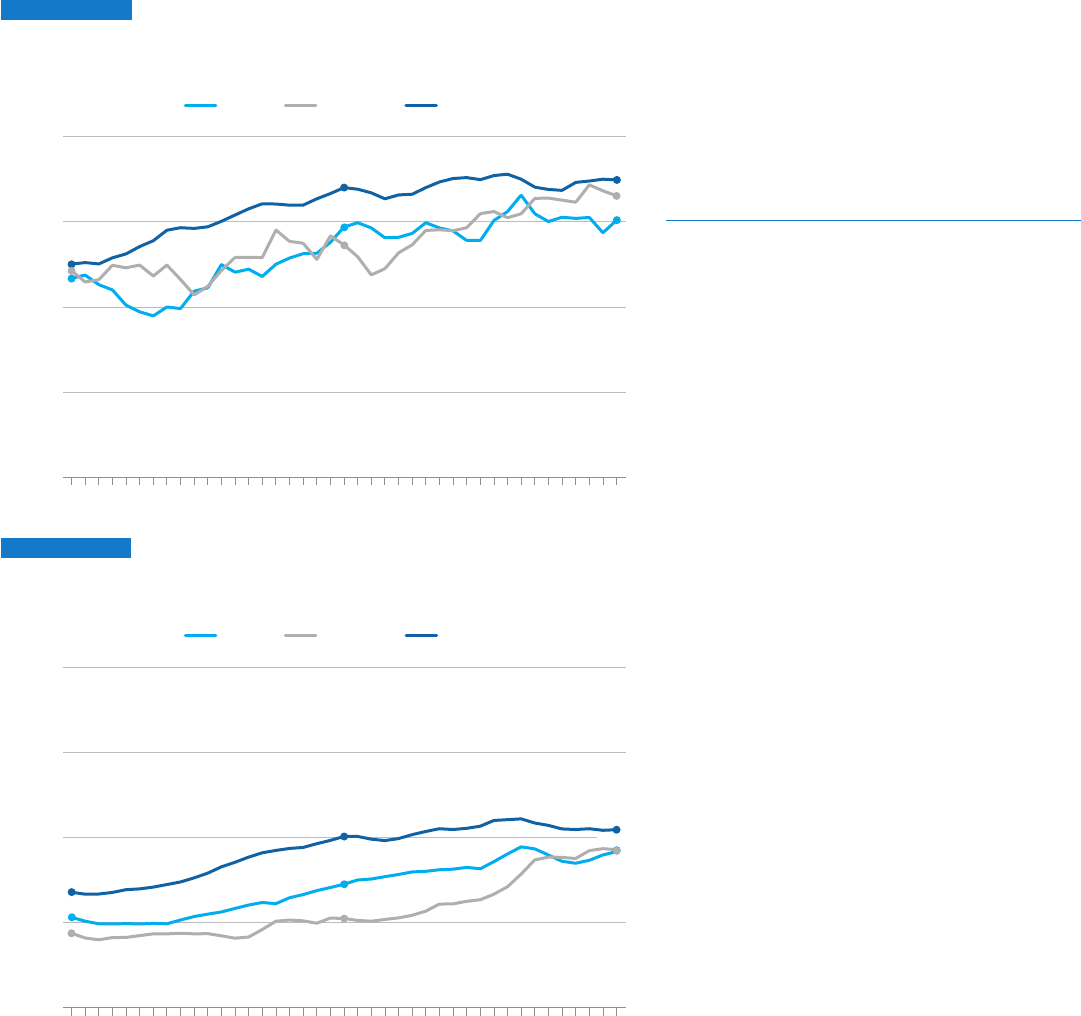

FIGURE 1.1A Postsecondary Enrollment Rates of Recent High School Graduates

by Race/Ethnicity, 1978 to 2018

50%

48%

47%

68%

59%

55%

70%

66%

60%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

1978 1983 1988 1993 2003 2013 2018

1998 2008

Enrollment Rate

Recent High School Graduates

Hispanic WhiteBlack

FIGURE 1.1B Postsecondary Enrollment Rates of All 18- to 24-Year-Olds by

Race/Ethnicity, 1978 to 2018

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

1978 1983 1988 1993 2003 2013 2018

1998 2008

Enrollment Rate

All 18- to 24-Year-Olds

27%

17%

21%

40%

21%

29%

42%

37%

37%

Hispanic

WhiteBlack

Enrollment rates of young adults between the

ages of 18 and 24 are lower than enrollment rates

of all recent high school graduates.

In 1998, 29% of black and 21% of Hispanic young

adults between the ages of 18 and 24 were enrolled

in college, compared with 40% of white young

adults. In 2018, enrollment rates were 37% for

black and Hispanic and 42% for white young adults.

ALSO IMPORTANT:

College enrollment rates are higher for Asians than

for other racial/ethnic groups. In 2018, 83% of Asians

enrolled in college within a year of graduating from

high school. (NCES, Digest of Education Statistics,

2019, Table 302.20; calculations by the authors)

Dierences in high school graduation rates account

for some of the college enrollment gaps graphed in

Figure 1.1B. In 2016-17, 89% of white, 78% of black,

and 80% of Hispanic public high school students

graduated from high school in four years. (NCES,

Digest of Education Statistics, 2018, Table 219.47)

NOTES: “Recent high school graduates” include those who graduated from high school in the

previous 12 months. “All 18- to 24-year-olds” also include those who have not completed high

school. “Postsecondary enrollment rates” are three-year moving averages and include both

undergraduate and graduate students. Some 18- to 24-year-olds have completed college and are

no longer enrolled. Because of small sample sizes for Hispanics and blacks, annual uctuations in

enrollment rates may not be signicant.

SOURCES: National Center for Education Statistics (NCES),

Digest of Education Statistics, 2019, Tables 302.20 and 302.60;

calculations by the authors.

11

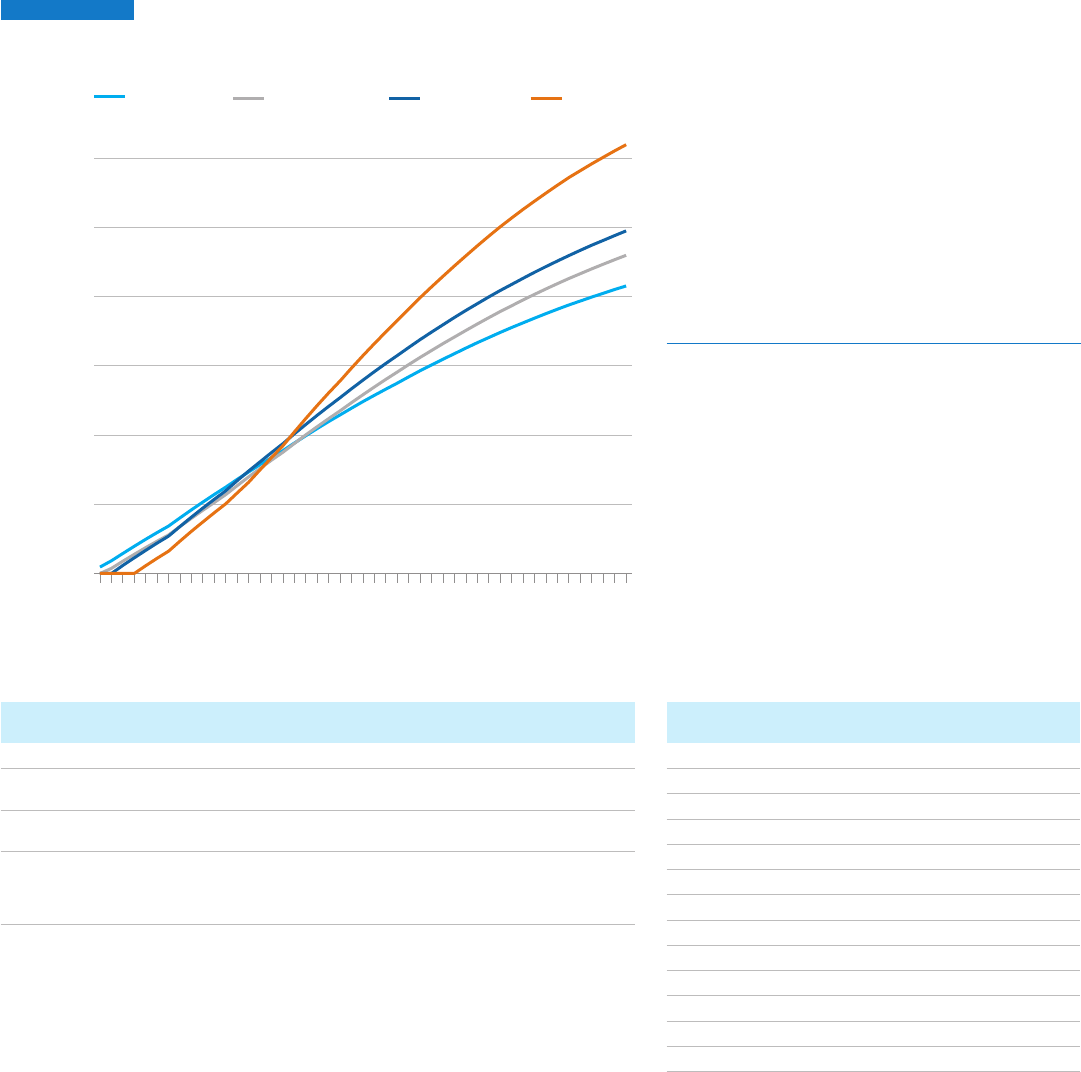

College Enrollment by Gender

In 1998, 62% of male and 70% of female recent high school graduates enrolled in college

within one year of high school graduation. In 2018, enrollment rates were 65% and 72%

for male and female students, respectively.

FIGURE 1.2A Postsecondary Enrollment Rates of Recent High School Graduates

by Gender, 1978 to 2018

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

1978 1983 1988 1993 2003 2013 2018

1998 2008

Enrollment Rate

Recent High School Graduates

Female

Male

50%

50%

62%

70%

65%

72%

FIGURE 1.2B Postsecondary Enrollment Rates of All 18- to 24-Year-Olds by

Gender, 1978 to 2018

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

1978 1983 1988 1993 2003 2013 2018

1998 2008

Enrollment Rate

All 18- to 24-Year-Olds

Female

Male

28%

35%

24%

38%

38%

44%

Since 1989, the college enrollment rate of recent

female high school graduates has consistently

exceeded that of recent male high school graduates.

In 2018, 38% of all male and 44% of all female young

adults between the ages of 18 and 24 were enrolled

in college. The gender gap in enrollment for this

age group was 3 percentage points in 1998 and

6 percentage points in 2008.

ALSO IMPORTANT:

In 1977, female students accounted for 49% of all

college students. By 2017, this percentage had grown

to 57%. (NCES, Digest of Education Statistics, 2018,

Table 303.10)

NOTES: “Recent high school graduates” include those who graduated from high school in the

previous 12 months. “All 18- to 24-year-olds” also include those who have not completed high

school. “Postsecondary enrollment rates” are three-year moving averages and include both

undergraduate and graduate students. Some 18- to 24-year-olds have completed college

and are no longer enrolled.

SOURCES: NCES, Digest of Education Statistics, 2019, Tables

302.10 and 302.60; calculations by the authors.

For detailed data behind the graphs and additional information, please visit: research.collegeboard.org/trends.

12

EDUCATION PAYS 2019 Part 1: Distribution of Benets

College Enrollment by Math Score

and Socioeconomic Status

Among students with similar high school math test scores, college enrollment rates are higher

for those from higher socioeconomic status (SES) quintiles than for those from lower SES quintiles.

FIGURE 1.3A Postsecondary Enrollment Status in 2016 by Math Quintile and

Parents’ Socioeconomic Status: High School Class of 2013

46%

28%

36%

17%

18%

72%

57%

16%

54%

47%

18%

65%

Lowest

Two SES

Quintiles

(54%)

All Middle

SES

Quintile

(22%)

Highest

Two SES

Quintiles

(24%)

Lowest Two Math

Quintiles (38%)

Percentage of High School Graduates

82%

86%

94%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

Lowest

Two SES

Quintiles

(43%)

Middle

SES

Quintile

(23%)

Highest

Two SES

Quintiles

(34%)

Middle Math

Quintile (19%)

Lowest

Two SES

Quintiles

(25%)

Middle

SES

Quintile

(17%)

Highest

Two SES

Quintiles

(58%)

Highest Two Math

Quintiles (44%)

63%

68%

86%

46%

49%

67%

63%

71%

85%

17%

19%

19%

18%

16%

9%

Currently

Enrolled or

Attained a

Credential

Left

College

Without a

Credential

FIGURE 1.3B Sector of First Postsecondary Institution by Math Quintile and

Parents’ Socioeconomic Status: High School Class of 2013

18%

39%

41%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

Lowest

Two SES

Quintiles

All Middle

SES

Quintile

Highest

Two SES

Quintiles

Lowest Two Math

Quintiles

Percentage of Students

Lowest

Two SES

Quintiles

Middle

SES

Quintile

Highest

Two SES

Quintiles

Middle Math

Quintile

Lowest

Two SES

Quintiles

Middle

SES

Quintile

Highest

Two SES

Quintiles

Highest Two Math

Quintiles

For-Prot

Public 2-Year

Public 4-Year

Private

Nonprot

4-Year

10%

16%

69%

11%

18%

67%

13%

28%

57%

9%

23%

65%

11%

25%

62%

17%

38%

43%

16%

44%

37%

16%

44%

39%

26%

54%

19%

For the high school class of 2013, gaps in college

enrollment rates between students from dierent

SES backgrounds are larger for those with lower

math scores.

w

Among students in the lowest two math quintiles,

46% of those from the lowest two SES quintiles

had enrolled in college by 2016 (three years after

high school graduation), and 65% of those from

the highest two SES quintiles had enrolled.

w

Among students in the highest two math

quintiles, 82% of low-SES and 94% of high-SES

students had enrolled in college by 2016.

High-SES students are more likely to enroll in a

public or private nonprot 4-year institution than

their lower-SES peers with similar math scores.

ALSO IMPORTANT:

Figure 1.3B shows the sectors of rst institutions

students attended. Some students begin in one

sector before transferring to another type of

institution. For example, about 30% of students who

rst enrolled in a public 2-year college in 2012 had

transferred to a 4-year institution by 2018. (Shapiro

et al., 2019, Table 4a)

NOTES: Math quintiles were based on students’ 11th-grade math

scores. Socioeconomic status was measured by a composite

score of parental education, occupations, and family income in

2011 when students were in 11th grade. Components may not

sum to totals because of rounding.

SOURCES: NCES, High School Longitudinal Study of 2009;

PowerStats calculations by the authors.

13

For detailed data behind the graphs and additional information, please visit: research.collegeboard.org/trends.

College Completion Rates

Within each sector, students with higher family incomes were more likely to complete a degree

than their lower-income peers with similar high school GPAs.

FIGURE 1.4 Six-Year Completion Rates by Sector, High School GPA, and Family

Income: 2011-12 Beginning Postsecondary Students

Associate DegreeBachelor’s Degree

5%

5%

60%

74%

13%

8%

66%

77%

32%

23%

33%

45%

55%

40%

55%

63%

52%

62% 6%

75%

61%

68%

80%

61%

81%

89%

63%

84%

90%

49%

60%

66%

58%

67%

69%

61%

80%

84%

63%

83%

85%

80%

84%

80%

87%

93%

93%

6%

12%

18%

23%

32%

35%

15%

19%

30%

34%

42%

52%

12%

31%

31%

33%

55%

46%

8%

23%

16%

33%

19%

36%

18%

16%

7%

10%

8%

9%

9%

7%

17%

20%

17%

19%

22%

23%

21%

24%

15%

15%

17%

16%

Public 4-year

Private Nonprot

4-year

Public 2-year

For-Prot

Low Income

Middle Income

High Income

Low Income

Middle Income

High Income

Low Income

Middle Income

High Income

Low Income

Middle Income

High Income

Low Income

Middle Income

High Income

Low Income

Middle Income

High Income

Low Income

Middle Income

High Income

Low Income

Middle Income

High Income

Low Income

Middle Income

High Income

Low Income

Middle Income

High Income

Overall Sector

Completion Rate

2.9 and

Lower

3.0 to 3.4

3.5 to 4.0

2.9 and

Lower

3.0 to 3.4

3.5 to 4.0

2.9 and

Lower

3.0 to 3.4

3.5 to 4.0

Public 4-YearPrivate Nonprot 4-YearPublic 2-YearFor-Prot

0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

Completion Rate

Among public 4-year students in the highest high

school GPA (HSGPA) category, 63% of low-income

students completed a degree within 6 years while

90% of high-income students did.

Among public 4-year students in the lowest HSGPA

category, 40% of low-income students completed

a degree within 6 years while 63% of high-income

students did.

Among undergraduate students who started

college for the rst time in 2011-12, 66% of those

whose rst enrollment was at a public 4-year

institution and 77% of those who started at a

private nonprot 4-year institution completed

either an associate or a bachelor’s degree within

6 years. In contrast, 32% of public 2-year students

and 23% of for-prot students completed an

associate or bachelor’s degree within 6 years.

ALSO IMPORTANT:

Figure 1.4 shows the shares of students who had

completed an associate or bachelor’s degree within

6 years. In addition, 2% of public 4-year, 1% of private

nonprot 4-year, 8% of public 2-year, and 24% of

for-prot students had completed a certicate within

6 years. (NCES, BPS 2012/2017; calculations by the

authors)

Full-time students are more likely to complete

credentials than part-time students. Among students

who rst enrolled in college in 2012, 80% of those

who enrolled full time had completed a credential

6 years later while only 21% of those who enrolled

part time had. (Shapiro et. al., 2018, Table 16)

While students’ academic preparation is perhaps

the most important predictor of their likelihood

of completing a credential, studies have shown

that initial college choice has a causal impact on

completion. For example, among college students

in the public sector, access to 4-year institutions

substantially increases bachelor’s degree

completion rates, particularly for low-income

students. (Goodman, Smith, & Hurwitz, 2015)

NOTES: Includes rst-time undergraduate students who

began their study in 2011-12. Completion status was as of

June 2017. Parents’ income groups of dependent students

were based on 2010 income: Low (less than $50,000),

Middle (between $50,000 and $99,999), and High ($100,000

or higher). For-prot sector is not broken down by HSGPA

because of small sample size. Components may not sum to

totals because of rounding.

SOURCES: NCES, Beginning Postsecondary Students

2012/2017; PowerStats calculations by the authors.

14

EDUCATION PAYS 2019 Part 1: Distribution of Benets

Educational Attainment

The percentage of young adults in the U.S. between the ages of 25 and 34 with at least

a bachelor’s degree grew from 11% in 1960 to 24% in 1980 and 1990. In 2018, 39% of adults

in this age group had earned at least a bachelor’s degree.

FIGURE 1.5A Educational Attainment of Individuals Age 25 to 34, 1940 to 2018,

Selected Years

64%

49%

42%

26%

15%

14%

12%

12%

8%

22%

32%

36%

44%

40%

41%

31%

27%

26%

7%

9%

11%

14%

22%

22%

28%

28%

28%

6%

5%

11%

16%

24%

24%

29%

33%

39%

1940

1950

1960

1970

1980

1990

2000

2010

2018

Less than a

High School

Diploma

High School

Diploma

Some College

or Associate

Degree

Bachelor’s

Degree or

Higher

NOTE: Percentages may not sum to 100 because of rounding.

SOURCE: U.S. Census Bureau, Educational Attainment in the United States, 2018, Table A-1.

FIGURE 1.5B Educational Attainment of Individuals by Age Group, 2018

8%

10%

10%

14%

26%

25%

31%

33%

18%

15%

16%

16%

10%

11%

11%

8%

39%

39%

33%

29%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

Bachelor’s Degree

or Higher

Associate Degree

Some College,

No Degree

High School Diploma

Less than a High

School Diploma

NOTE: Percentages may not sum to 100 because of rounding.

SOURCE: NCES, Digest of Education Statistics, 2018, Table 104.30.

The percentage of adults age 25 to 34 with some

college or an associate degree grew rapidly in

the 1970s and again in the 1990s. It has stabilized

since 2000 at 28%.

In 1940, 86% of adults in the U.S. age 25 to 34 had

no postsecondary education experience. By 1980,

that percentage had decreased to 55% and has

since decreased by another 21 percentage points

to 34% in 2018.

In 2018, about 10% of adults age 25 to 49 held

an associate degree, and 39% held at least a

bachelor’s degree.

ALSO IMPORTANT:

The fact that the earnings dierential between

high school graduates and college graduates has

increased over time despite the increasing prevalence

of college degrees indicates that the demand for

college-educated workers in the labor market has

increased more rapidly than the supply. (See Goldin &

Katz [2008] and Autor [2010] for discussion of the

failure of the supply of college graduates to keep up

with the demand.)

According to the Organisation for Economic

Co-operation and Development (OECD), Korea had

the highest educational attainment among all OECD

countries in 2018 with 70% of 25- to 34-year-olds

having completed tertiary education. (OECD, 2019,

Chart A1.2)

25 to 34 35 to 49 50 to 64 65 and Older

15

For detailed data behind the graphs and additional information, please visit: research.collegeboard.org/trends.

Educational Attainment by Race/Ethnicity

and Gender

Among blacks, whites, and Hispanics between the ages of 25 and 29, females outpace males

in terms of both high school and bachelor’s degree completion. This gender gap emerged in

the 1990s.

FIGURE 1.6 Percentage of 25- to 29-Year-Olds Who Have Completed High School

or a Bachelor’s Degree, by Race/Ethnicity and Gender, 1978 to 2018

76%

81%

88%

92%

92%

74%

12%

84%

86%

87%

87%

13%

13%

17%

18%

21%

20%

25%

12%

12%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

Black, Non-Hispanic

At Least a High School Diploma At Least a Bachelor’s Degree

FemaleMaleFemaleMale

1978 1983 1988 1993 1998 2003 2008 2013 2018

7%

9%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

Hispanic

56%

59%

59%

62%

60%

65%

62%

70%

81%

85%

8%

15%

17%

22%

10%

11%

9%

10%

1978 1983 1988 1993 1998 2003 2008 2013 2018

88%

89%

29%

22%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

White, Non-Hispanic

25%

24%

34%

31%

39%

32%

47%

39%

89%

90%

92%

94%

93%

95%

95%

96%

1978 1983 1988 1993 1998 2003 2008 2013 2018

Between 1978 and 2018, the percentage of

black females age 25 to 29 who held a bachelor’s

degree nearly doubled from 13% to 25%, while the

percentage of black males with a bachelor’s degree

increased from 12% to 20%.

Between 1978 and 2018, the percentage of Hispanic

females age 25 to 29 who held a bachelor’s degree

tripled from 7% to 22%, while the percentage of

Hispanic males with a bachelor’s degree nearly

doubled from 9% to 17%.

Between 1978 and 2018, the percentage of white

females age 25 to 29 who held a bachelor’s degree

more than doubled from 22% to 47%, while the

percentage of white males with a bachelor’s degree

increased from 29% to 39%.

Between 2008 and 2018, the percentage of white

and Hispanic males or females age 25 to 29 with

a bachelor’s degree increased by about 7 to 9

percentage points, while the increase was about

2 to 4 percentage points among black males or

females over this time period.

ALSO IMPORTANT:

The share of all young adults age 25 to 29 with at

least a bachelor’s degree was 36% in 2018; this share

ranged from 19% for Hispanics and 23% for blacks to

43% for whites and 66% for Asians. (NCES, Digest of

Education Statistics, 2018, Table 104.30)

NOTE: Attainment rates are three-year moving averages.

SOURCES: NCES, The Condition of Education, 2007, Table 27;

Digest of Education Statistics, 2018, Table 104.30.

16

EDUCATION PAYS 2019 Part 1: Distribution of Benets

College Enrollment and Attainment by State

The percentage of 18- to 24-year-olds enrolled in college in 2017 ranged from 29% in Alaska

and 31% in Nevada to 56% in the District of Columbia and 57% in Rhode Island.

FIGURE 1.7 Postsecondary Enrollment Rates of 18- to 24-Year-Olds and

Percentage of All Adults with at Least a Bachelor’s Degree in 2017

57%

56%

53%

49%

49%

48%

48%

46%

46%

46%

45%

45%

45%

44%

44%

44%

44%

44%

43%

43%

43%

43%

42%

42%

42%

41%

41%

41%

41%

41%

40%

40%

39%

39%

39%

39%

39%

39%

38%

38%

37%

37%

37%

37%

35%

35%

34%

34%

33%

33%

31%

29%

0% 20% 40% 60%

34%

57%

44%

32%

34%

38%

36%

40%

37%

29%

40%

39%

30%

37%

29%

32%

31%

36%

34%

33%

32%

30%

31%

22%

27%

41%

34%

28%

28%

34%

28%

29%

31%

26%

24%

34%

31%

29%

30%

20%

27%

24%

24%

25%

36%

33%

27%

28%

27%

31%

25%

29%

0%20%40%60%

% of Adults with at Least a

Bachelor’s Degree

% of 18- to 24-Year-Olds Enrolling

in Postsecondary Education

RI

DC

MA

DE

CA

CT

NY

NJ

NH

MI

MD

VA

WI

VT

IA

PA

NE

MN

IL

ME

US

FL

ND

MS

IN

CO

UT

SC

OH

KS

SD

MO

NC

AL

LA

OR

GA

AZ

TX

WV

TN

KY

AR

OK

WA

HI

ID

WY

NM

MT

NV

AK

SOURCES: NCES, Digest of Education Statistics, 2018, Tables 104.88 and 302.65.

In 2017, the percentage of adults age 25 and older

with at least a bachelor’s degree ranged from 20%

in West Virginia and 22% in Mississippi to 44% in

Massachusetts and 57% in the District of Columbia.

Iowa, Michigan, Nebraska, and Wisconsin have

college enrollment rates above the national

average of 43%, but bachelor’s degree attainment

rates are slightly lower than the national average

of 32%.

ALSO IMPORTANT:

In 2018, median household income in the United

States was $63,200. Median household income was

under $50,000 in Mississippi, New Mexico, Arkansas,

Alabama, and Louisiana; it was over $80,000 in Hawaii,

New Hampshire, District of Columbia, Maryland, and

Massachusetts. (U.S. Census Bureau, Social and

Economic Supplement, Table H-8)

17

For detailed data behind the graphs and additional information, please visit: research.collegeboard.org/trends.

Education, Earnings, and Tax Payments

In 2018, median earnings of bachelor’s degree recipients with no advanced degree working full time

were $24,900 higher than those of high school graduates. Bachelor’s degree recipients paid an estimated

$7,100 more in taxes and took home $17,800 more in after-tax income than high school graduates.

On average, taxes take a larger share of the incomes of

individuals with higher earnings, so the after-tax earnings

premium is slightly smaller than the pretax earnings premium.

Median earnings for individuals with associate degrees working

full time were 24% higher than median earnings for those with

only a high school diploma. After-tax earnings were 22% higher.

The median total tax payments of full-time workers with a

professional degree in 2018 were over 3.7 times as high as the

median tax payments of high school graduates working full time.

After-tax earnings were about 2.8 times as high.

ALSO IMPORTANT:

In 2018, 76% of 4-year college graduates age 25 and older had

earnings and 59% worked full time; 59% of high school graduates

age 25 and older had earnings, and 44% worked full time.

Not all the dierences in earnings reported here may be attributable to

education level. Educational credentials are correlated with a variety of

other factors that aect earnings, including parents’ socioeconomic

status and some personal characteristics.

While the average high school graduate may not earn as much as the

average college graduate simply by obtaining a bachelor’s degree,

rigorous research on the subject suggests that the gures cited here

do not measurably overstate the nancial return to higher education.

(Card, 2001; Carneiro, Heckman, & Vytlacil, 2011; Rouse, 2005; Harmon,

Oosterbeek, & Walker, 2003; Oreopoulos & Petronijevic, 2013)

FIGURE 2.1 Median Earnings and Tax Payments of Full-Time Year-Round Workers Age 25 and Older, by Education Level, 2018

$120,500

$102,300

$80,200

$65,400

$50,100

$46,300

$30,800

Professional Degree (2%)

Doctoral Degree (3%)

Master’s Degree (12%)

Bachelor’s Degree (27%)

Associate Degree (11%)

Some College,

No Degree (15%)

High School

Diploma (25%)

Less than a High

School Diploma (6%)

$0 $20,000 $40,000 $60,000 $80,000 $100,000 $120,000

$32,400

$26,700

$20,100

$15,800

$11,400

$10,300

$8,700

$6,200

$88,100

$75,600

$60,100

$49,600

$38,700

$36,000

$31,800

$24,600

$40,500

Estimated Taxes

After-Tax Income

NOTES: The percentages in parentheses on the vertical axis indicate the shares of all full-time year-round workers age 25 and older with each education level in

2018. The bars in this graph show median earnings at each education level. The light blue segments represent the estimated average federal income, Social Security,

Medicare, state and local income, sales, and property taxes paid at these income levels. The dark blue segments show after-tax earnings. Percentages may not sum

to 100 because of rounding.

SOURCES: U.S. Census Bureau, Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance in the United States, 2018, Table PINC-03; Internal Revenue Service, 2017; Wiehe et al., 2018;

calculations by the authors.

18

EDUCATION PAYS 2019 Part 2: Individual and Societal Benets

Earnings Premium Relative

to Price of Education

The typical 4-year college graduate who enrolls at age 18 and graduates in four years can expect

to earn enough relative to a high school graduate by age 33 to compensate for being out of the labor

force for four years and for borrowing the full tuition and fees and books and supplies without any grant aid.

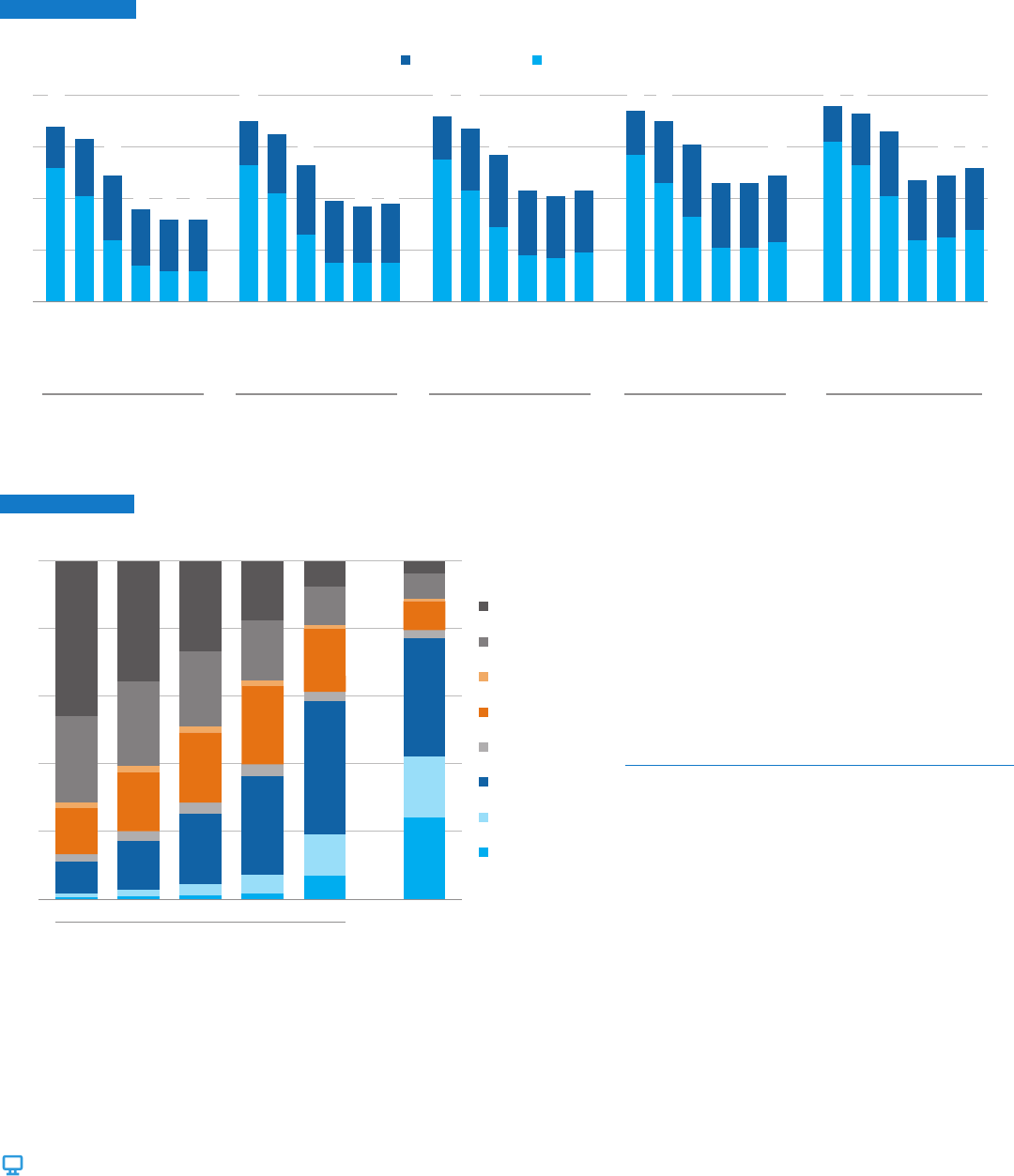

FIGURE 2.2A Estimated Cumulative Full-Time Median Earnings (in 2017 Dollars)

Net of Loan Repayment for Tuition and Fees and Books and Supplies,

by Education Level

High School

Diploma

Some College,

No Degree

Associate

Degree

Bachelor’s

Degree

$0

$200,000

$400,000

$600,000

$800,000

$1,000,000

$1,200,000

Cumulative Net Earnings

Age

18 20 22 24 26 28 30 32 34 36 38 40 42 44 46 48 50 52 54 56 58 60 62 64

Assumptions for Figure 2.2A

Age Starting

Full-Time Work

Price of Tuition and Fees

and Books and Supplies

High School 18 None

Some College, No Degree 19 Weighted average of public 2-year and public

4-year price. 2017-18: $9,230.

Associate Degree 20 Average public 2-year price.

2017-18: $4,960; 2018-19: $5,070.

Bachelor’s Degree 22 Weighted average of public and private

nonprot 4-year price. 2017-18: $18,840;

2018-19: $19,300; 2019-20: $19,830;

2020-21: $20,420.

NOTES: Excludes bachelor’s degree recipients who earn advanced degrees. Assumes students

borrow the cost of tuition and fees and books and supplies and pay it o over 10 years after

graduation with a 4.45% annual interest rate during and after college. Tuition/loan payments

and earnings are discounted at 3%, compounded every year beyond age 18. The 2020-21 price

is projected using the 2019-20 price and a 3% annual increase.

SOURCES: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2013–2017 Five-Year Public Use

Microdata Sample; College Board, Trends in College Pricing, 2019; calculations by the authors.

For the typical associate degree recipient who

pays the published tuition and fees and books

and supplies at a community college and earns

an associate degree 2 years after high school

graduation, total earnings exceed those of high

school graduates by age 31.

For the typical student who attends a public

college for a year and leaves without a degree,

total earnings exceed those of high school

graduates by age 36.

The longer college graduates remain in the

workforce, the greater the payo to their

investment in higher education.

ALSO IMPORTANT:

Figure 2.2A shows the cumulative earnings for

full-time year-round workers. Individuals with higher

levels of education are more likely to work full time

year-round than those with lower levels of education.

Figure 2.2A shows the cumulative earnings using

median earnings and weighted average 4-year tuition

and fees and books and supplies. Results using some

alternative assumptions are shown in Figure 2.2B.

Median Earnings by Education Level and Age, 2013–2017

Age

High School

Diploma

Some College,

No Degree

Associate

Degree

Bachelor’s

Degree

18 $18,600 $0 $0 $0

19 $18,600 $16,600 $0 $0

20 $22,600 $23,000 $25,600 $0

21 $22,600 $23,000 $25,600 $0

22 to 24 $22,600 $23,000 $25,600 $35,400

25 to 29 $29,300 $31,400 $35,400 $46,000

30 to 34 $31,900 $37,100 $41,200 $55,200

35 to 39 $36,300 $41,900 $46,600 $65,700

40 to 44 $37,300 $45,500 $49,500 $70,800

45 to 49 $40,100 $47,800 $51,800 $74,300

50 to 54 $41,200 $49,400 $52,300 $75,800

55 to 59 $41,200 $49,600 $52,600 $73,600

60 to 64 $40,400 $49,300 $52,300 $70,000

19

For detailed data behind the graphs and additional information, please visit: research.collegeboard.org/trends.

Earnings Premium Relative to Price

of Education: Alternative Scenarios

The break-even age (age at which cumulative earnings of college graduates exceed those

of high school graduates) increases with amount of time students take to earn their degrees.

Grant aid that reduces the net price of college shortens the break-even period.

FIGURE 2.2B Age at Which Cumulative Earnings of College Graduates Exceed

Those of High School Graduates, by Degree and College Cost

31

37

30

33

36

30

0

10

20

30

40

2 Years of

Average

Public

2-Year

Published

Price

3 Years of

Average

Public

2-Year

Published

Price

2 Years of

Average

Public

2-Year

Net Price

4 Years of

Average

Public

and Private

Nonprot

4-Year

Published

Price

5 Years of

Average

Public and

Private

Nonprot

4-Year

Published

Price

4 Years of

Average

Public and

Private

Nonprot

4-Year

Net Price

Associate Degree Bachelor’s Degree

Break-even Age Compared with

High School Graduates

Tuition and Fees and Books and Supplies

Assumptions for Figure 2.2B

Education Level

Age Starting

Full-Time Work

Price of Tuition and Fees and Books

and Supplies

High School 18 None

Associate Degree

Baseline (2 years of average public

2-year published price)

20 2017-18: $4,960; 2018-19: $5,070.

3 years of average public 2-year

published price

21 2017-18: $4,960; 2018-19: $5,070;

2019-20: $5,190.

2 years of average public 2-year

net price

20 2017-18: $910; 2018-19: $980.

Bachelor’s Degree

Baseline (4 years of average public

and private nonprot 4-year

published price)

22 2017-18: $18,840; 2018-19: $19,300;

2019-20: $19,830; 2020-21: $20,420.

5 years of average public and private

nonprot 4-year published price

23 2017-18: $18,840; 2018-19: $19,300;

2019-20: $19,830; 2020-21: $20,420;

2021-22: $21,030.

4 years of average public and private

nonprot 4-year net price

22 2017-18: $7,990; 2018-19: $8,030;

2019-20: $8,350; 2020-21: $8,600.

The break-even age depends on the length of study.

As an example, for students paying the published

price and taking 5 years to complete a bachelor’s

degree, the break-even age is 36. Full-pay students

who complete a bachelor’s degree in four years

have a projected break-even age of 33.

Compared with high school graduates with median

earnings working full time, the break-even age

for associate degree recipients with median

earnings is 31 if they pay the average public 2-year

published tuition and fees and books and supplies

for 2 years. The break-even age increases to 37 if

they pay these expenses for 3 years; it is 30 if they

receive the average amount of grant aid and pay

net tuition and fees and buy books and supplies

for two years.

ALSO IMPORTANT:

The calculations for Figures 2.2A and 2.2B are based

on median earnings for full-time year-round workers.

There is considerable variation in earnings within

each education level (Figure 2.3).

Figures 2.2A and 2.2B assume that students have

no earnings while attending school full time. Many

students work part time while in school.

NOTES: Excludes bachelor’s degree recipients who earn

advanced degrees. Assumes students borrow the cost of

tuition and fees and books and supplies and pay it o over

10 years after graduation with a 4.45% annual interest rate

during and after college. Tuition/loan payments and earnings

are discounted at 3%, compounded every year beyond age 18.

The 2020-21 and 2021-22 prices are projected using the

2019-20 price and a 3% annual increase.

SOURCES: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey,

2013–2017 Five-Year Public Use Microdata Sample; College

Board, Trends in College Pricing, 2019; calculations by

the authors.

20

EDUCATION PAYS 2019 Part 2: Individual and Societal Benets

Variation in Earnings Within Levels

of Education

Median earnings are higher for those with higher levels of education, but there is considerable

variation in earnings at each level of educational attainment.

The percentage of full-time year-round workers age 35 to 44

earning $100,000 or more in 2018 ranged from 2% of those

without a high school diploma and 5% of high school graduates

to 28% of those whose highest attainment was a bachelor’s

degree and 43% of advanced degree holders.

In 2018, while 5% of all full-time year-round workers age 35 to 44

earned less than $20,000, 20% of those without a high school

diploma and 8% of those with only a high school diploma were

in this income category. In contrast, only 2% of those whose

highest attainment was a bachelor’s degree and 1% of those

with advanced degrees fell into this category.

In 2018, 19% of all full-time year-round workers age 35 to 44

held advanced degrees, 27% held bachelor’s degrees, while

23% held only a high school diploma and 7% did not graduate

from high school.

ALSO IMPORTANT:

Figure 2.3 includes only full-time year-round workers. The

percentage of individuals who are employed rises with level of

education, as does the percentage of those employed who work

full time. (Bureau of Labor Statistics, Labor Force Statistics from

the Current Population Survey)

Figure 2.3 includes workers between the ages of 35 and 44, an age

group when the majority of full-time workers have nished school

and started a career.

Some of the variation in earnings is associated with elds of study,

occupation, and location. Earnings also dier by gender and

race/ethnicity. (Baum, Kurose, & Ma, 2013)

FIGURE 2.3 Earnings Distribution of Full-Time Year-Round Workers Age 35 to 44, by Education Level, 2018

$1 to

$19,999

$40,000 to

$59,999

$20,000 to

$39,999

$60,000 to

$79,999

$80,000 to

$99,999

$100,000

and over

2%

1%

2%

50%20%

40%8%

32%6%

27%4%

15%

5%

20%

27%

27%

31%

22%

18%

5%

2%

14%

18%

19%

20%

18%

5%

9%

10%

13%

15%

5%

9%

10%

28%

43%

25%5% 24% 17% 10% 19%

Less than a High School Diploma (7%)

High School Diploma (23%)

Some College, No Degree (14%)

Associate Degree (11%)

Bachelor’s Degree (27%)

Advanced Degree (19%)

All (100%)

NOTES: The percentages shown in parentheses on the vertical axis represent shares of all full-time year-round workers age 35 to 44 with each education level.

Percentages may not sum to 100 because of rounding.

SOURCES: U.S. Census Bureau, Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance in the United States, 2018, PINC-03; calculations by the authors.

21

For detailed data behind the graphs and additional information, please visit: research.collegeboard.org/trends.

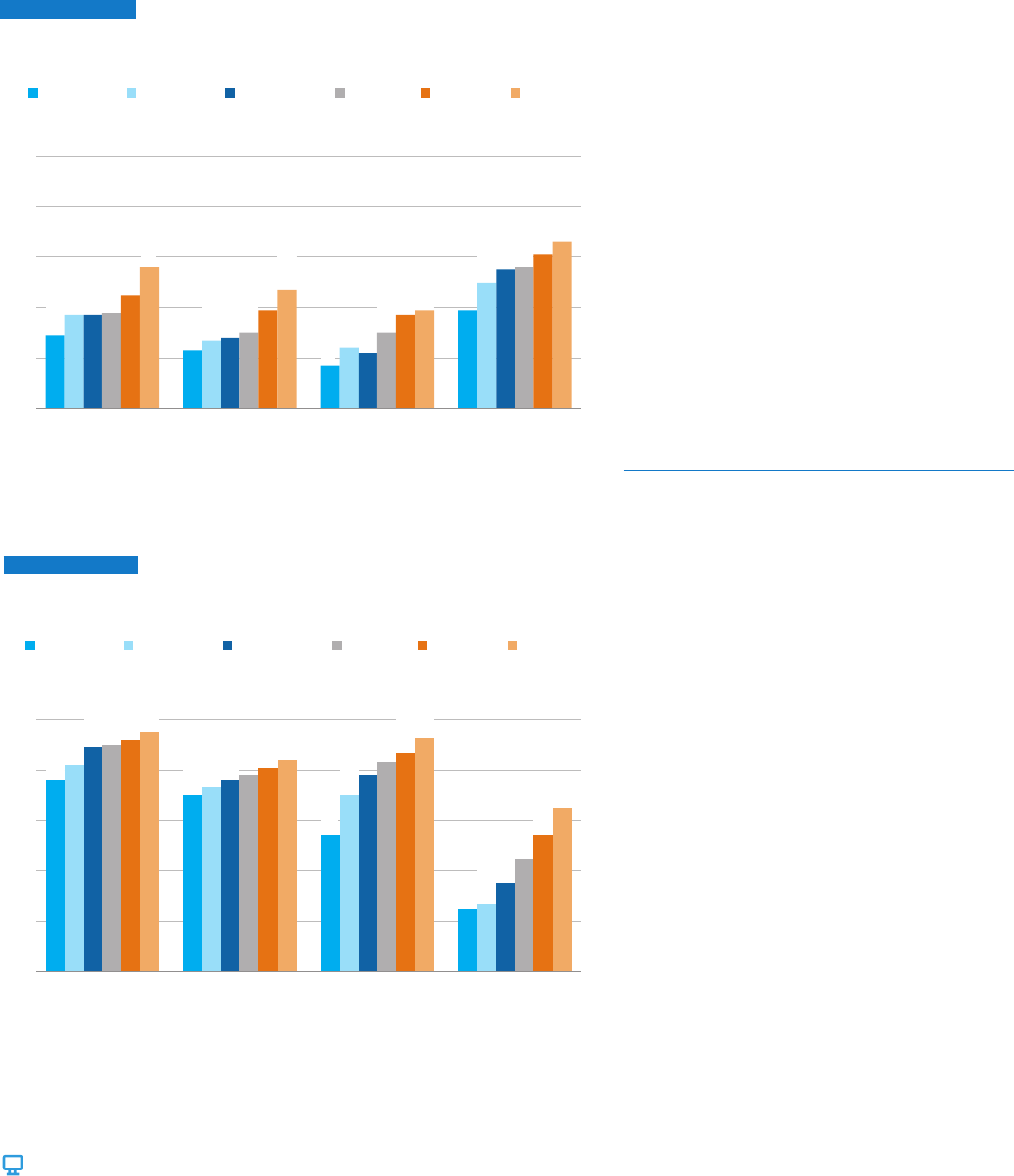

Earnings by Race/Ethnicity,

Gender, and Education Level

Between 2016 and 2018, median earnings of individuals age 25 to 34 working full time

year-round with a bachelor’s degree ranged from $42,100 among black females and $43,900

among Hispanic females to $72,300 among Asian males.

FIGURE 2.4 Median Earnings (in 2018 Dollars) of Full-Time Year-Round Workers Age 25 to 34, by Race/Ethnicity, Gender, and Education Level,

2016–2018

Median Earnings

$0

$20,000

$40,000

$60,000

$80,000

$100,000

Less than a

High School Diploma

High School

Diploma

Some College,

No Degree

Associate

Degree

Bachelor’s

Degree

Advanced

Degree

$21,600

$26,800

$31,100

$31,300

$42,100

$56,000

$28,500

$31,500

$36,600

$40,500

$47,600

$70,600

Black

$28,700

$34,800

$40,900

$41,800

$72,300

$89,100

$18,700

$29,100

$31,900

$33,500

$56,100

$75,700

Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Male

Asian

$23,000

$26,900

$31,100

$33,900

$43,900

$57,300

Hispanic White All

$29,300

$26,500

$33,000

$23,500

$30,400

$35,300

$31,000

$40,700

$29,200

$37,400

$39,500

$32,300

$43,200

$31,600

$41,100

$41,100

$35,400

$49,000

$34,100

$46,000

$51,600

$50,200

$62,000

$48,500

$60,800

$69,900

$60,200

$76,200

$60,900

$77,200

NOTES: Based on combined data from the 2017, 2018, and 2019 Annual Social and Economic Supplement of the Current Population Survey. Earnings in 2016

and 2017 are adjusted to 2018 dollars using the Consumer Price Index for all urban consumers. Median earnings are the medians of combined data. The “Asian,”

“Black,” and “White” categories include individuals who reported one race only and who reported non-Hispanic.

SOURCES: U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey, Annual Social and Economic Supplement, 2017, 2018, and 2019; calculations by the authors.

The earnings premium for a bachelor’s degree relative to a high

school diploma was the highest among Asian males and females,

whose median earnings were about twice as high as for those

with a high school diploma.

The earnings gap between 25- to 34-year-old associate degree

recipients and high school graduates working full time ranged

from 14% ($4,400) among white females to 29% ($9,000) among

black males.

Among full-time workers age 25 to 34, median earnings of white

males with a bachelor’s degree were 23% higher than median

earnings of white females with a bachelor’s degree. The gender

gaps were: 29% among Asian, 17% among Hispanic, and 13%

among black bachelor’s degree recipients.

ALSO IMPORTANT:

Between 2016 and 2018, the proportion of individuals age 25 to 34

working full time year-round ranged from 41% for those without a

high school diploma to 70% for those with an advanced degree.

Ratio of Median Earnings of Bachelor’s Degree Recipients to Median

Earnings of High School Graduates, by Race/Ethnicit

y and Gender,

Full-Time Year-Round Workers, 2016–2018

Asian Female

BA/HS Earnings Ratio

Age 25 to 34 Age 25 and Older

1.93 2.05

Male 2.08 1.94

Black Female 1.57 1.67

Male 1.51 1.50

Hispanic Female 1.63 1.62

Male 1.46 1.51

White Female 1.62 1.57

Male 1.52 1.61

All Female 1.66 1.69

Male 1.63 1.68

22

EDUCATION PAYS 2019 Part 2: Individual and Societal Benets

Earnings by Gender and Education Level

Earnings of full-time year-round workers are strongly correlated with level of education,

but there is considerable variation in earnings among both men and women at each level

of educational attainment.

In 2018, median earnings of female 4-year college graduates were

$56,700. This exceeded median earnings of female high school

graduates by 74% ($24,100). Median earnings of male bachelor’s

degree recipients were $75,200. This exceeded median earnings

of male high school graduates by 65% ($29,600).

In 2018, 25% of females with a college degree earned less than

$40,500 and 25% earned more than $81,600. Among male college

graduates, 25% earned less than $50,400 and 25% earned above

$110,000.

In 2018, 61% of males with some college education but no degree

and 68% of males holding associate degrees earned more than

the median earnings of male high school graduates ($45,600).

In 2018, 61% of females with some college education but no degree

and 67% of females holding associate degrees earned more than

the median earnings of female high school graduates ($32,600).

ALSO IMPORTANT:

In 2018, 14% of female high school graduates earned more than

the median for female college graduates, and 15% of female

college graduates earned less than the median for female high

school graduates.

In 2018, 17% of male high school graduates earned more than the

median for male college graduates, and 21% of male college graduates

earned less than the median for male high school graduates.

Figure 2.5 includes only full-time year-round workers ages 25 and

older. Among both men and women, the percentage of individuals who

are employed rises with level of education, as does the percentage of

those employed who are working full time. (Bureau of Labor Statistics,

Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey)

FIGURE 2.5

Median, 25th P

er

centile, and 75th Percentile Earnings of Full-Time Year-Round Workers Age 25 and Older, by Gender and

Education Level, 2018

Less than a

High School

Diploma

Some College,

No Degree

Bachelor’s

Degree

Doctoral

Degree

Less than a

High School

Diploma

Some College,

No Degree

Bachelor’s

Degree

Doctoral

Degree

High School

Diploma

Associate

Degree

Master’s

Degree

Professional

Degree

High School

Diploma

Associate

Degree