1

A Report

to the Nation

February 2001

Some 2 million American workers are victims of workplace violence each year.

Violence in the workplace. Every few days, there is another story on the news. One day, it may be a convenience store shooting;

the next, a sexual assault in a company parking lot; a few days later, it’s a disgruntled employee holding workers hostage,

or a student attacking a teacher.

Not surprisingly, the incidents of workplace violence that make the news are only the tip of the iceberg. What its victims all have in

common is that they were at work, going about the business of earning a living, but something about their workplace environment—

often something foreseeable and preventable—exposed them to attack by a customer, a co-worker, an acquaintance, or even a

complete stranger.

Some 2 million American workers are victims of workplace violence each year. It is estimated that costs of workplace violence to

employers is in the billions of dollars. Unfortunately, research into the prevention of violence in the workplace is still in its infancy.

In April 2000, The University of Iowa Injury Prevention Research Center took an important first step to meet this need by sponsoring

the Workplace Violence Intervention Research Workshop in Washington, DC. The goal of this workshop was to examine issues related

to violence in the workplace and to develop recommended research strategies to address this public health problem. The workshop

brought together 37 invited participants representing diverse constituencies within industry, organized labor, municipal, state, and

federal governments, and academia. The following is a summary of the problem of workplace violence and the recommendations

identified by participants at the workshop.

Solid information on what works, and what doesn’t, is urgently needed.

4

of customer/client incidents occur in the health care industry,

in settings such as nursing homes or psychiatric facilities; the

victims are often patient caregivers. Police officers, prison staff,

flight attendants, and teachers are some other examples of

workers who may be exposed to this kind of workplace violence.

Worker-on-Worker (Type III): The perpetrator is an employee or

past employee of the business who attacks or threatens another

employee(s) or past employee(s) in the workplace. Worker-on-

worker fatalities account for approximately 7% of all workplace

violence homicides.

Personal Relationship (Type IV): The perpetrator usually does

not have a relationship with the business but has a personal

relationship with the intended victim. This category includes

victims of domestic violence assaulted or threatened while

at work.

These categories can be very helpful in the design of strategies to

prevent workplace violence, since each type of violence requires a

different approach for prevention, and some workplaces may be at

higher risk for certain types of violence.

How often does workplace violence occur? An essential problem

with efforts to reduce workplace violence is that data are scattered

and sketchy, making it very difficult to study what works and what

doesn’t work to reduce violence in the workplace. The best data

available cover fatal events. There is less information available

concerning injuries from non-fatal events, economic impact on

businesses affected, lost productivity and other costs. Various

data collection systems have different ways of defining “at work,”

especially when there are ambiguities such as commuting and

. . . homicide remains the third leading cause of fatal occupational injuries for all

workers and the second leading cause of fatal occupational injuries for women

The Extent of the Problem

Workplace violence is receiving increased attention thanks to a

growing awareness of the toll that violence takes on workers and

workplaces. Despite existing research, there remain significant

gaps in our knowledge of its causes and potential solutions.

Even the extent of violence in the workplace and the number of

victims are not well understood.

In 1999, the Bureau of Labor Statistics recorded 645 homicides in

workplaces in the United States. Although this figure represents a

decline from a high of 1,080 in 1994, homicide remains the third

leading cause of fatal occupational injuries for all workers and the

second leading cause of fatal occupational injuries for women.

The number of non-fatal assaults is less clear. The National Crime

Victimization Survey, a weighted annual survey of 46,000

households, estimates that an additional 2 million people are

victims of non-fatal injuries due to violence while they are at work.

Addressing this problem is complicated, because workplace

violence has many sources. To better understand its causes and

possible solutions, researchers have divided workplace violence

into four categories. Most incidents fall into one of these categories:

Criminal Intent (Type I): The perpetrator has no legitimate

relationship to the business or its employees, and is usually

committing a crime in conjunction with the violence. These crimes

can include robbery, shoplifting, and trespassing. The vast

majority of workplace homicides (85%) fall into this category.

Customer/Client (Type II): The perpetrator has a legitimate

relationship with the business and becomes violent while being

served by the business. This category includes customers, clients,

patients, students, inmates, and any other group for which the

business provides services. It is believed that a large proportion

Type I: Criminal Intent

n May 2000, two men entered a Wendy’s in Flushing, NY, with the intent to rob the fast-food

restaurant. They left with $2,400 in cash after shooting seven employees. Five of the employees died and two

others were seriously injured.

This is an extreme example of Type I workplace violence: violence committed during a robbery or similar crime in the

workplace. Type I is the most common source of worker homicide. Eighty-five percent of all workplace homicides fall into

this category. Although the shootings in Flushing drew a great deal of media attention, the vast majority of these

incidents barely make the news. Convenience store clerks, taxi drivers, security guards, and proprietors of “mom-and-

pop” stores are all examples of the kinds of workers who are at higher risk for Type I workplace violence.

In Type I incidents:

• The perpetrator does not have any legitimate business relationship with the establishment;

• The primary motive is usually theft;

• A deadly weapon is often involved, increasing the risk of fatal injury;

• Workers who exchange cash with customers as part of the job, work late night hours, and/or work alone are at

greatest risk.

5

travel, volunteers or students in a workplace, or workplaces that

are also residences, such as farms or home offices. Sources of

information such as police, physician, workers’ compensation, or

employee reports may capture only one element—the violent

incident, or the injury, or the lost work time, or the setting (at

work)—but not the whole picture of the trauma resulting from

violence in the workplace. Finally, many non-fatal incidents,

especially threats, simply go unreported, in part because there is

no coordinated data-collection system to process this information.

Prevention

There are three general approaches to preventing workplace

violence:

• Environmental: adjusting lighting, entrances and exits, security

hardware, and other engineering controls to discourage

would-be assailants;

• Organizational/Administrative: developing programs, policies,

and work practices aimed at maintaining a safe working

environment;

• Behavioral/Interpersonal: training staff to anticipate, recognize

and respond to conflict and potential violence in the workplace.

There has not been adequate research, however, into the

effectiveness of these approaches for all types (I-IV) of workplace

violence. For example, most research to date on criminal intent

(Type I) violence in retail settings has focused only on environmen-

tal approaches. Although there have been some promising initial

findings, more research is needed to help businesses properly

protect their employees. Very little research has been conducted

on behavioral/interpersonal or organizational/administrative

approaches to prevention.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) has

developed voluntary guidelines for the prevention of workplace

violence, including guidelines for specific industries such as late-

night retail, health care and social service, and community

workers. However, the effectiveness of these recommendations

has yet to be fully evaluated. Funding is urgently needed to

evaluate these guidelines.

The most troubling problem with existing research is that very

little of it has been conducted using rigorous scientific methods.

One of the papers prepared for this workshop (Peek-Asa, Runyan,

and Zwerling; see “Resources” on page 13 for more information)

describes a comprehensive review of research to date. The authors

raised a variety of concerns with a large proportion of the

research, including sample sizes that were too small, a lack of

appropriate control groups, publication without peer review, and

other problems. This lack of good research severely hampers

efforts to address the problem of violence in the workplace.

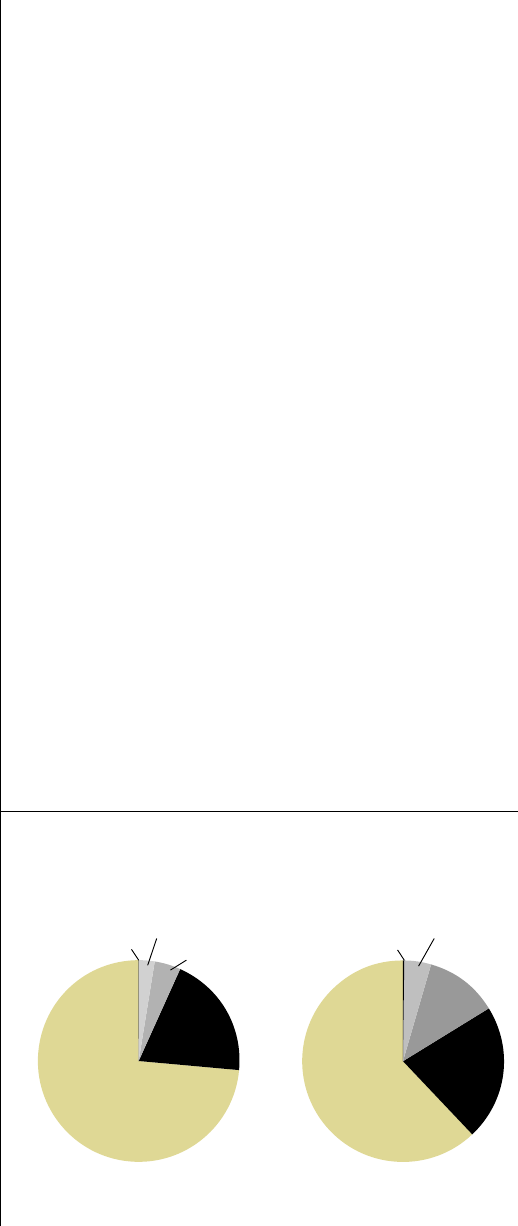

Rape and sexual assault 4.3%

Homicide 0.2%

Robbery

11.7%

Aggravated

assault

21.7%

Simple assault

62%

Rape and sexual assault 2.5%

Homicide 0.05% Robbery

4.2%

Aggravated

assault

19.7%

Simple assault

73.6%

Victims of Violence, 1992-96

Victimization in the Workplace All Victimizations

Source: National Crime Victimization Study, July 1998

6

Type II: Customer/Client

honda Bedow, a nurse who works in a state-

operated psychiatric facility in Buffalo, NY, was

attacked by an angry patient who had a history of

threatening behavior, particularly against female

staff. He slammed Bedow’s head down onto a counter after

learning that he had missed the chance to go outside with

a group of other patients. Bedow suffered a concussion,

a bilaterally dislocated jaw, an eye injury, and permanent

scarring on her face from the assault. She still suffers from

short-term memory problems resulting from the attack.

When she returned to work after recuperating, the

perpetrator was still on her ward, and resumed his threats

against her.

In Type II incidents, the perpetrator is generally a customer

or client who becomes violent during the course of a

normal transaction. Service providers, including health

care workers, schoolteachers, social workers, and bus and

train operators, are among the most common targets of

Type II violence. Attacks from “unwilling” clients, such as

prison inmates on guards or crime suspects on police

officers, are also included in this category.

In Type II incidents:

• The perpetrator is a “customer” or a client of the worker;

• The violent act generally occurs in conjunction with the

worker’s normal duties;

• The risk of violence to some workers in this category

(e.g., mental health workers, police) may be constant,

even routine.

7

8

Industry

Some employers have responded to the problem of workplace

violence by implementing measures to reduce the risk to their

employees. Different industries have different kinds of risks

depending on a multitude of factors, including the type of

business, populations served, management, employees, location

of the workplace, layout of the work area, and the relationship of

that business with the community.

Employers have attempted to increase safety by various means,

including:

• Physical security enhancements, such as lighting and cash

handling procedures, that make it more difficult to carry out a

violent assault (All Types);

• Threat management procedures, such as a team-oriented plan of

action in the case of a violent incident (All Types);

• Employee Assistance Programs (EAPs), to provide intervention

for at-risk employees (Type III and IV);

• “Zero tolerance” policies related to threatening or harassing

behavior (Type III);

• Employee training, to promote recognition of hazards and

appropriate responses to incidents of violence (All Types);

• Screening, to identify potentially high-risk employees (Type III);

• Company policies and training to facilitate employee comfort in

reporting threatening behaviors (All Types) and timely manage-

ment response to the employee reports;

• Hiring of security firms that specialize in prevention of

workplace violence (All Types).

In workplaces that have only infrequent incidents of violence,

many employers find it difficult to decide which safety measures

are most appropriate. This is especially true when faced with very

expensive or labor-intensive interventions. Private security

services and consultants abound, but there is limited scientific

information on which strategies work best for the various types of

There is no national legislation nor are there any federal regulations specifically

addressing the prevention of workplace violence.

Laws and Regulations

Federal: There is no national legislation nor are there any federal

regulations specifically addressing the prevention of workplace

violence. OSHA has published voluntary guidelines for workers in

late-night retail, health care, and taxicab businesses, but employ-

ers are not legally obligated to follow these guidelines.

State: To date, several states have passed legislation or enacted

regulations aimed at reducing workplace violence in specific

industries. California and Washington have enacted regulations

aimed at reducing patient-employee (Type II) violence in health

care settings. At least three states (Florida, Virginia, and Washing-

ton) have laws or regulations intended to prevent robbery-related

homicides (Type I) in late-night retail establishments such as

convenience stores. The Florida law is the most comprehensive.

Many convenience stores in Florida have found it easier to simply

close for business during the late-night hours (11 p.m. to 5 a.m.)

rather than make the changes required by the law. Neither the

legal changes nor the store closings have been evaluated as

strategies to prevent workplace violence.

State OSHA regulations: The states of California and Washington

both enforce regulations requiring comprehensive safety programs

in all workplaces, including the prevention of “reasonably

foreseeable” assault on employees.

Local: Taxi drivers appear to have by far the highest risk of fatal

assault of any occupation. Safety ordinances, such as those

requiring bullet-proof barriers in taxicabs, have appeared in

several U.S. cities, including Los Angeles, Chicago, New York City,

Baltimore, Boston, Albany (NY), and Oakland (CA). More study is

needed to assess these approaches.

Type III: Worker-on-Worker

ype III violence occurs when an employee assaults or attacks his or her co-workers. In some cases,

these incidents can take place after a series of increasingly hostile behaviors from the perpetrator.

Worker-on-worker assault is often the first type of workplace violence that comes to mind for many people,

possibly because some of these incidents receive intensive media coverage, leading the public to assume that most

workplace violence falls into this category. For example, the phrase “going postal,” referring to the scenario of a postal

worker attacking co-workers, is sometimes used to describe Type III workplace violence. However, the U.S. Postal Service

is no more likely than any other industry to be affected by this type of violence.

Type III violence accounts for about 7% of all workplace homicides. There do not appear to be any kinds of

occupations or industries that are more or less prone to Type III violence. Because some of these incidents appear to be

motivated by disputes, managers and others who supervise workers may be at greater risk of being victimized.

In Type III incidents:

• The perpetrator is an employee or former employee;

• The motivating factor is often one or a series of interpersonal or work-related disputes.

9

10

characteristics, say its critics, is not an effective predictor of

potentially violent behavior and may raise discrimination issues.

In general, labor unions favor an increase in voluntary implemen-

tation of workplace violence intervention by employers, coupled

with some mandatory provisions such as state legislation or a

mandatory OSHA standard. Labor also recognizes the need for

more research to determine which current OSHA guidelines and

other types of interventions are most effective in preventing

violent incidents in the workplace.

Recommended Workplace Violence Research Agenda

Workshop participants identified specific areas of research

needed for each of the four types of workplace violence. Interven-

tion research questions that need to be addressed include:

Criminal Intent (Type I):

• What are people doing now?

What factors predict employers’ choices of strategies to

prevent workplace violence?

How can employers choose appropriate workplace violence

prevention consultants?

Are current training programs effective?

• How effective are the OSHA guidelines?

• How many businesses are voluntarily complying with

OSHA guidelines?

• Do industry-specific environmental, organizational/administrative,

and behavioral/interpersonal control strategies work?

Client/Customer on Employee (Type II):

• How do staffing and the organization of work affect violence in

the health care setting?

• How effective are the OSHA guidelines?

workplace violence. In addition, businesses are often reluctant

to make their security methods public, not wanting to alarm

customers or tip off potential perpetrators, which makes it difficult

to evaluate those methods.

Employers are often in a difficult position when it comes to

responding appropriately to the problem of workplace violence.

They must avoid over-reacting, under-reacting, or reacting in a way

that exacerbates the problem. In addition, businesses may face

serious legal implications with some security measures. For

example, some kinds of pre-employment screening may be viewed

as discriminatory, but an employer could also face a “negligent

hiring” lawsuit if an applicant with a past history of violence is hired.

Labor

In the past decade, representatives of organized labor have

pushed for the recognition of workplace violence as an

occupational hazard, not just a criminal justice issue. Of particular

concern is the high rate of violent incidents targeting health care

workers (Type II violence). On some psychiatric units, for example,

assault rates on staff are greater than 100 cases per 100 workers

per year. Unions representing workers in the health care industry

suspect that “short-staffing” may play a role in this problem, but

there is little research into this issue to date.

Organized labor professionals or representatives have also

expressed concerns about workplace violence interventions that

target employee behavior, such as “zero tolerance” policies and

“worker profiling” designed to identify employees or potential

employees at risk for violent behavior. There is concern that zero

tolerance policies may be unevenly enforced and that they fail to

address some of the root causes of violence, such as stress or

situations leading to conflict. Profiling based on personal

. . . representatives of organized labor have pushed for the recognition of workplace violence as an

occupational hazard, not just a criminal justice issue.

11

Type IV: Personal Relationship

amela Henry, an employee of Protocall, an

answering service in San Antonio, had decided in the

summer of 1997 to move out of the area. The abusive

behavior of her ex-boyfriend, Charles Lee White,

had spilled over from her home to her workplace, where he

appeared one day in July and assaulted her. She obtained

and then withdrew a protective order against White, citing

her plans to leave the county. On October 17, 1997, White

again appeared at Protocall. This time he opened fire with

a rifle, killing Henry and another female employee before

killing himself.

Because of the insidious nature of domestic violence, it is

given a category all its own in the typology of workplace

violence. Victims are overwhelmingly, but not exclusively,

female. The effects of domestic violence on the workplace are

many. They can appear as high absenteeism and low

productivity on the part of a worker who is enduring abuse or

threats, or the sudden, prolonged absence of an employee

fleeing abuse. Occasionally, the abuser—who usually has no

working relationship to the victim’s employer—will appear at

the workplace to engage in hostile behavior.

In some cases, a domestic violence situation can arise

between individuals in the same workplace. These situations

can have a substantial effect on the workplace even if one of

the parties leaves or is fired.

Type IV violence:

• Is the spillover of domestic violence into the workplace;

• Generally refers to perpetrators who are not employees or

former employees of the affected workplace;

• Targets women significantly more often than men,

although both male and female co-workers and supervisors

are often affected.

12

. . . our understanding of workplace violence is still in its infancy. Much remains to be done

in the area of research, particularly in data collection and in intervention.

• How extensive is voluntary compliance with OSHA guidelines in

the health care industry?

• Do industry-specific environmental, organizational/administra-

tive, and behavioral/interpersonal control strategies work?

Worker-on-Worker (Type III):

• What is the relationship between corporate culture, the

organization of the workplace, security, and worker-on-worker

violence?

• How can public health data on threats and violence be improved?

• Are “zero tolerance” policies and profiling effective?

Personal Relationships (Type IV):

• How big is the problem? What is the impact of domestic violence

on the workplace?

• What strategies have been used by labor and management to

address this problem? How effective have they been?

• What is the legal situation? What duties do employers have

under state laws? Are there legal barriers to early interventions?

• Can businesses play a critical role in changing social norms

regarding domestic violence?

Conclusion

Workplace violence affects us all. Its burden is borne not only by

victims of violence, but by their co-workers, their families, their

employers, and by every worker at risk of violent assault—in other

words, virtually all of us. Although we know that each year

workplace violence results in hundreds of deaths, more than 2

million injuries, and billions of dollars in costs, our understanding

of workplace violence is still in its infancy. Much remains to be

done in the area of research, particularly in data collection and in

intervention. Without basic information on who is most affected

and which prevention measures are effective in what settings,

we can expect only limited success in addressing this problem.

The first steps have been taken. With the help of a broad coalition,

a number of key issues have been identified for future research.

However, research funding focused on a much broader under-

standing of the scope and impact of workplace violence is urgently

needed to reduce the human and financial burden of this signifi-

cant public health problem.

0 50,000 100,000 150,000 200,000 250,000 300,000

Retail sales

Teaching

Medical

Mental health

Transportation

Private security

Law enforcement

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

Type I:

Criminal intent

Type II:

Customer/Client

Type III:

Co/Past Worker

Type IV:

Personal relationship

85

3

7

5

Average Annual Number of Violent Non-Fatal

Victimizations in the Workplace, 1992-96

By Selected Occupations

Source: National Crime Victimization Study, July 1998

Total number of homicides=860 Source: Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries, BLS

Percent of Work-Related Homicides by Type, United States, 1997

13

Acknowledgements

This workshop would not have been successful without the

support of several agencies and individuals. We would like to

thank the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health

(NIOSH) and the National Center for Injury Prevention and

Control (NCIPC) for the generous financial support that made the

workshop possible. We received valuable advice throughout the

process by the workshop’s planning committee: Ann Brockhaus

from Organization Resources Counselors; Lynn Jenkins from

NIOSH; Keith Lessner from the Alliance of American Insurers;

Corrine Peek-Asa from the Southern California Injury Prevention

Research Center; and Robyn Robbins of the United Food and

Commercial Workers International Union. The unique mix of

participants invited to the workshop is a credit to the planning

committee’s efforts. The review paper authors are to be

commended for their hard work spent preparing, presenting, and

revising their papers. While many persons too numerous to list

contributed to this workshop, we would like to single a few out for

special recognition. Injury Prevention Research Center Director

Craig Zwerling provided leadership throughout the process.

Associate Editor Leslie Loveless spent countless hours writing and

editing the reports and papers resulting from this workshop.

Carrie Kiser-Wacker from the UI’s Center for Conferences and

Institutes ensured that the workshop ran smoothly. And finally,

we would like to thank Carol Runyan for her closing summary at

the workshop and for writing the response paper.

We hope that the papers and recommendations from this workshop

will be the catalyst for a national initiative on workplace violence

intervention research. We appreciate the opportunity to organize

the workshop, which has produced this report to the nation.

James A. Merchant, MD, Dr PH, Dean and Professor

College of Public Health

Director, Public Policy Core

John A. Lundell, MA

Deputy Director

The University of Iowa Injury Prevention Research Center

Workshop Co-Directors

Resources

Five review papers, each addressing a specific aspect of workplace

violence, were prepared in conjunction with the workshop.

They appear in the February 2001 issue of the American Journal

of Preventive Medicine, at www.elsevier.com/locate/ajpmonline.

The papers are:

Barish RC. Legislation and Regulations Addressing Workplace

Violence in the U. S. and British Columbia.

Peek-Asa C, Runyan CW, Zwerling C. The Role of Surveillance and

Evaluation Research in the Reduction of Violence Against Workers.

Rosen J. A Labor Perspective of Workplace Violence Prevention:

Identifying Research Needs.

Runyan CW. Moving Forward with Research on the Prevention of

Violence Against Workers.

Wilkinson CW. Violence Prevention At Work: A Business

Perspective.

Up-to-date information and statistics on workplace violence are

available at the following web sites:

The OSHA web site on workplace violence, which includes

recommendations for prevention at http://www.osha.gov

The Bureau of Labor Statistics web site: http://stats.bls.gov

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health:

http://www.cdc.gov/niosh

National Center for Injury Prevention and Control:

http://www.cdc.gov/ncipc

American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees:

http://www.afscme.org/health/faq-viol.htm

California OSHA web site on Workplace Security:

http://www.dir.ca.gov/DOSH/dosh_publications/index.html

14

Participants

David Alexander

George Meany Center for Labor

Studies

Silver Spring, Maryland

Ileana Arias, PhD

Division of Violence Prevention

National Center for Injury

Prevention and Control

Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention

Atlanta, Georgia

Michael Arrighi

The Steele Foundation

Richmond, Virginia

Robert Barish

CAL/OSHA

San Francisco, California

Michele Beauchamp

OSH Compliance and Regulatory

Development

HRDC Labour Program

Ottawa, Ontario

Patricia Biles

U.S. Department of Labor/OSHA

Washington, DC

Bill Borwegen

Service Employees International

Union

Washington, D.C.

Ann Brockhaus, MPH

Organization Resources

Counselors, Inc.

Washington, DC

Joanne Colucci

American Express Company

New York, New York

Detis T. Duhart, PhD

Bureau of Justice Statistics

Department of Justice

Washington, DC

Raymond B. Flannery, Jr., PhD

Massachusetts Department of

Mental Health

Boston, Massachusetts

Lynn Jenkins, MA

Division of Safety Research

National Institute for Occupa-

tional Safety and Health

Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention

Morgantown, West Virginia

Spurgeon Kennedy

Office of Development and

Communication

National Institute of Justice

Washington, DC

Theodore Krey

The International Association of

Chiefs of Police

Alexandria, Virginia

Keith Lessner

Alliance of American Insurers

Downers Grove, Illinois

Jane Lipscomb, PhD

University of Maryland

School of Nursing

Baltimore, Maryland

Leslie Loveless, MPH

UI Injury Prevention

Research Center

Iowa City, Iowa

John A. Lundell, MA

UI Injury Prevention

Research Center

Iowa City, Iowa

Captain Jim McDonnell

Los Angeles Police Academy

Los Angeles, California

James A. Merchant, MD, DrPH

UI Injury Prevention

Research Center

Iowa City, Iowa

Sharon Ness, RN

Local 141, United Staff Nurses

Union, UFCW

Federal Way, Washington

Corinne Peek-Asa, PhD

UCLA SCIPRC

Los Angeles, California

Gwendolyn Puryear Keita, PhD

American Psychological

Association

Washington, DC

Robyn Robbins

United Food and Commercial

Workers International Union

Washington, DC

Jonathan Rosen, MS, CIH

New York State Public Employees

Federation

Latham, New York

Linda Rosenstock, MD

National Institute for

Occupational Safety and Health

Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention

Washington, DC

Eugene A. Rugala

National Center for the Analysis

of Violent Crime

Supervisory Special Agent

FBI Academy

Quantico, Virginia

Carol Runyan, PhD, MPH

UNC Injury Prevention

Research Center

Chapel Hill, North Carolina

Dan Sosin, MD, MPH

National Center for Injury

Prevention and Control

Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention

Atlanta, Georgia

Rebecca A. Speer, JD

Law Offices of Rebecca A. Speer

San Francisco, California

Larry Stoffman

Canadian Council UFCW

Vancouver, British Columbia

Jeff Thurston, MN, ARNP

Service Employees International

Union

Western State Hospital

Tacoma, Washington

Richard Titus, PhD

Office of Research and Evaluation

National Institute of Justice

Washington, DC

Barbara Webster

Liberty Mutual Research Center

for Safety and Health

Hopkinton, Maryland

Carol Wilkinson, MD, MPH

IBM Corporation

Armonk, New York

Jan Williams, CSW-R, BCD, CEAP

Corning Incorporated

Corning, New York

Craig Zwerling, MD, PhD, MPH

UI Injury Prevention

Research Center

Iowa City, Iowa

Additional copies of this report

are available from the UI IPRC,

100 Oakdale Campus, 158 IREH,

Iowa City, IA 52242-5000, or at

the IPRC web site at www.public-

health.uiowa.edu/iprc, or by

sending an e-mail to:

Editor: Leslie Loveless

Designer: Patti O’Neill

Illustrator: Luba Lukova

THE UNIVERSITY OF IOWA

R13/CCR717056-01

R49/CCR703640-11

17551/1-01

The first steps have been taken. Funding for research into what works,

and what doesn’t, is urgently needed.

AFSCME

UNION LABOR

16

THE UNIVERSITY OF IOWA

100 Oakdale Campus

158 IREH

Iowa City, IA 52242-5000