TECHNICAL REPORT

Systematic scoping review

on social media monitoring

methods and interventions

relating to vaccine hesitancy

www.ecdc.europa.eu

ECDC TECHNICAL REPORT

Systematic scoping review on social media

monitoring methods and interventions

relating to vaccine hesitancy

ii

This report was commissioned by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) and coordinated

by Kate Olsson with the support of Judit Takács.

The scoping review was performed by researchers from the Vaccine Confidence Project, at the London School of

Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (contract number ECD8894). Authors: Emilie Karafillakis, Clarissa Simas, Sam Martin,

Sara Dada, Heidi Larson.

Acknowledgements

ECDC would like to acknowledge contributions to the project from the expert reviewers: Dan Arthus, University

College London; Maged N Kamel Boulos, University of the Highlands and Islands, Sandra Alexiu, GP Association

Bucharest and Franklin Apfel and Sabrina Cecconi, World Health Communication Associates.

ECDC would also like to acknowledge ECDC colleagues who reviewed and contributed to the document: John

Kinsman, Andrea Würz and Marybelle Stryk.

Suggested citation: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Systematic scoping review on social

media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy. Stockholm: ECDC; 2020.

Stockholm, February 2020

ISBN 978-92-9498-452-4

doi: 10.2900/260624

Catalogue number TQ-04-20-076-EN-N

© European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2020

Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged

TECHNICAL REPORT Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy

iii

Contents

Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................................... iv

Glossary ....................................................................................................................................................... iv

Executive summary ........................................................................................................................................ 1

Introduction and background ..................................................................................................................... 1

Aims ........................................................................................................................................................ 1

Methods ................................................................................................................................................... 1

Results .................................................................................................................................................... 1

Discussion ................................................................................................................................................ 2

1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 4

2 Background ................................................................................................................................................ 5

3 Goals and objectives ................................................................................................................................... 7

4. Review methods ........................................................................................................................................ 8

4.1. Search strategy and database search ................................................................................................... 8

4.2. Screening and selection of articles ....................................................................................................... 8

4.3. Data extraction and analysis ................................................................................................................ 9

5. Review results ......................................................................................................................................... 10

5.1 Individuals’ preferences for using social media platforms as a source of information on vaccination and

social media’s influence on individuals’ perceptions of vaccination ............................................................... 11

5.2 Social media monitoring ..................................................................................................................... 12

5.3 Using social media monitoring to inform vaccination communication strategies ....................................... 29

5.4 Uses, benefits and limitations of social media as an intervention tool in relation to vaccination ................. 33

6. Discussion ............................................................................................................................................... 36

6.1 Use of social media for vaccination information .................................................................................... 36

6.2 Methodologies to monitor social media in relation to vaccination ........................................................... 36

6.3 Review how social media monitoring methods and information gathered from monitoring can be used to

inform communication strategies .............................................................................................................. 41

6.4 Understanding the uses, benefits and limitations of using social media as an intervention around vaccination .... 42

6.5 Limitations of this systematic scoping literature review ......................................................................... 43

7. Conclusions and the way forward .............................................................................................................. 44

References .................................................................................................................................................. 45

Annexes ...................................................................................................................................................... 52

Figures

Figure 1. Prisma flow diagram ....................................................................................................................... 10

Figure 2. Social media monitoring phases ....................................................................................................... 12

Figure 3. Number of articles published by type of social media and by year until 2018 ....................................... 15

Figure 4. Number of articles published by type of vaccine ................................................................................ 15

Figure 5. Number of articles published by country monitored ........................................................................... 16

Figure 6. Number of studies by type of social media monitoring tools used ....................................................... 17

Figure 7. Keywords most commonly used across all studies (>4 use) ................................................................ 21

Figure 8. Sentiment codes used across all studies ........................................................................................... 25

Figure 9. Number of studies using manual or automated sentiment coding, by social media ............................... 27

Tables

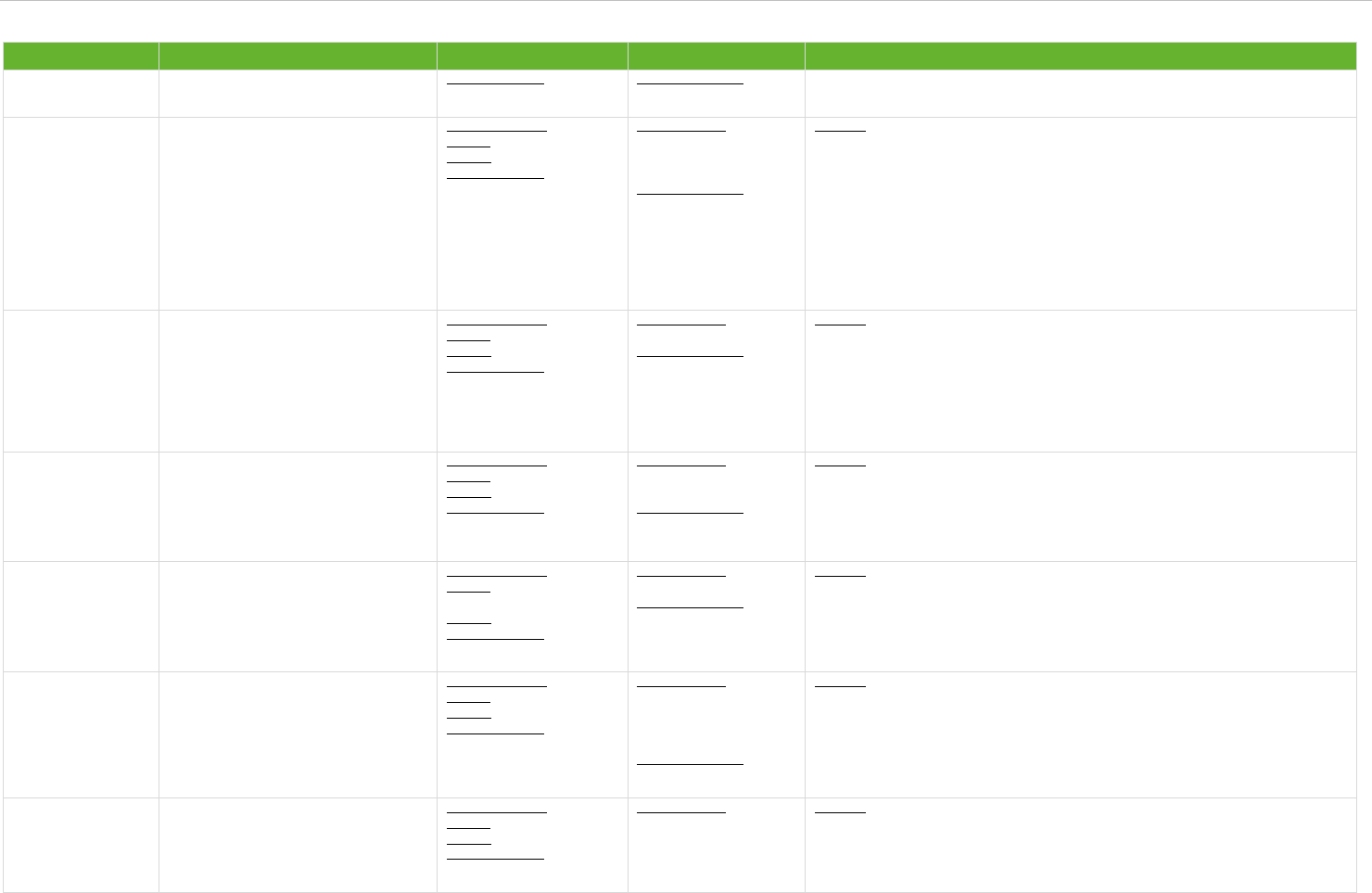

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for screening of articles ....................................................................... 8

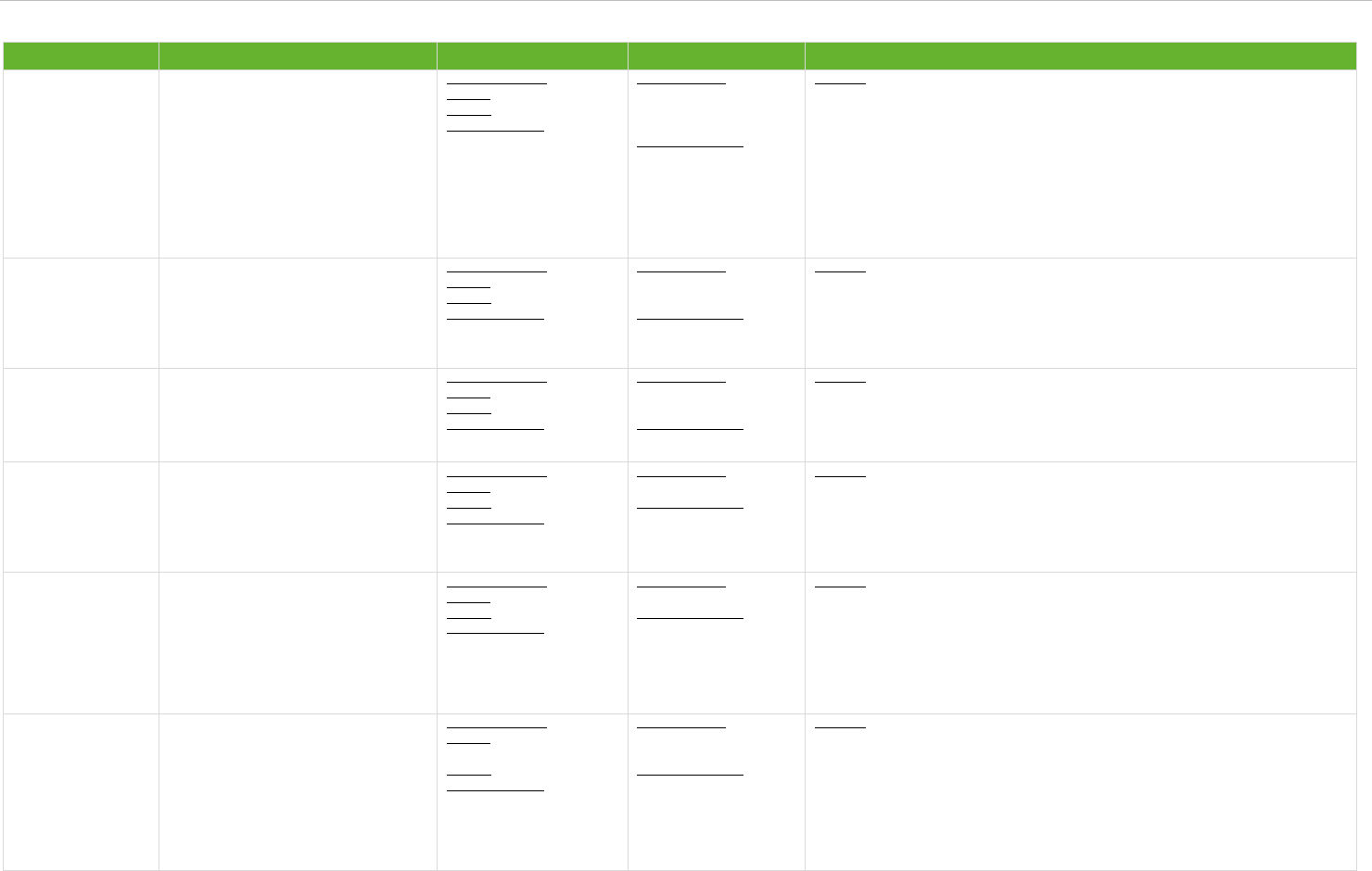

Table 2. Data extraction categories ................................................................................................................. 9

Table 3. Description of social media platforms identified in the scoping review .................................................. 14

Table 4. Different manual browser searches and limitations mentioned by the studies using the tool ................... 18

Table 5. Social media APIs and their limitations mentioned by the stuides using the tool .................................... 19

Table 6. List of codes, definitions and counts for sentiment analysis used in the identified studies ....................... 26

Table 7. Suggestions for increasing presence on social media identified in scoping review studies ..................................... 31

Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy TECHNICAL REPORT

iv

Abbreviations

AI Artificial Intelligence

API Application Programming Interface

CDC United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

ECDC European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control

HTML Hyper Text Markup Language

HPV Human Papillomavirus

GDPR General Data Protection Regulation

GPS Global Positioning System

LDA Latent Dirichlet Allocation

MMR Measles Mumps Rubella

PHP Hypertext Preprocessor

UK United Kingdom

URL Uniform Resource Locator

US United States

VCP Vaccine Confidence Project

TM

Glossary

Application Programming Interface Software allowing two applications to talk to each other (e.g.

smartphone software sending text/images to the Twitter

database/platform).

Global Positioning System A system of satellites, computers, and receivers able to determine the

geographical location of an object on Earth.

Latent Dirichlet Allocation A generative statistical model (in natural language processing) used for

topic extraction, representation and analysis from large datasets.

Hypertext Preprocessor Refers to how dynamic web pages (php) are created and accessed with

precompiled and pre-processed code linking to databases, so that

accessing them is faster and easier via different browsers.

Uniform Resource Locator A uniform resource locator is the address of a resource on the Internet.

Sentiment analysis A process that uses natural language processing, text analysis and

computational linguistics to identify positive, negative and neutral

opinions from text and social media.

Reach analysis Defined in social media as the number of people that see content - the

greater the reach, the higher number of people that have seen content.

Vanity metrics In social media vanity metrics are measured by engagement

(comments, shares, likes, clicks, and saves), providing information on

how many people are interacting with content on social media

platforms.

TECHNICAL REPORT Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions around vaccine hesitancy

1

Executive summary

Introduction and background

We are living in an interconnected world, where social media have become part of the everyday life of many

individuals around the globe. People use social media to stay connected to friends and family, to share personal

information, views or beliefs, or to seek information and gather other peoples’ advice about certain topics,

including health. These new communication technologies have also facilitated the recent spread of unsubstantiated

negative information about vaccination online, influencing individuals’ views about vaccination, their levels of

confidence in different vaccines and their willingness to be vaccinated or to vaccinate their children. The online

spread of rumours surrounding vaccination, including adverse events following vaccination, has contributed to the

growth of vaccine hesitancy and in some cases may have contributed to disease outbreaks in unvaccinated

populations. However, social media also constitute an opportunity to spread positive messages about the benefits

of vaccination and to restore trust in vaccination. Listening, monitoring and analysing social media conversations

concerning vaccination could help us to understand low vaccination acceptance and provide valuable information to

counteract the spread of rumours and misinformation.

In this report, social media have been defined as not just a means of communication, but also a space in which

people socialise. Social media are therefore seen as online environments or platforms that see ‘interaction’

as a

main purpose. This study focusses on social networking sites and content communities, which can be seen as more

relevant in the context of vaccination.

Aims

The aim of this research project is to map, analyse and summarise knowledge and research on social media and

vaccination. The key objectives were to identify preferences for using different social media platforms as a source

of information on vaccination and the influence that social media have on individuals’ perceptions of vaccination; to

identify different social media monitoring methods or tools in the context of vaccination and their strengths and

weaknesses; to review how social media monitoring methods and information gathered from monitoring can be

used to inform communication strategies, and to identify the uses, benefits and limitations of social media as an

intervention tool around vaccination (i.e. to determine how effective social media are as a tool for increasing

vaccination uptake).

Methods

In order to address these objectives, a systematic scoping review was commissioned by ECDC and conducted by

researchers at the Vaccine Confidence Project

TM

[1]. A comprehensive search strategy was developed, reviewed by

librarians, and adapted to different databases to identify peer-reviewed and grey literature published since 2000.

Two reviewers independently screened all articles by title and abstract and then by full text, based on a set of

inclusion and exclusion criteria. All disagreements were resolved by discussion. The articles included were divided

into three groups: a) preferences for using different social media platforms as a source of information on

vaccination and the influence that social media have on individuals’ perceptions of vaccination, b) social media

monitoring and c) social media interventions. Data extraction was performed by four reviewers and followed by a

descriptive analysis and synthesis.

Results

The systematic scoping review identified 115 articles: 13 on individuals’ preferences for using social media as a

source for vaccination information and any influence on perceptions of vaccination; 85 on social media monitoring,

15 on social media interventions, one on both social media monitoring and social media interventions, and one on

both social media interventions and individuals’ preferences for using social media as a source for vaccination

information and any influence on perceptions of vaccination.

Preferences for using different social media platforms as a source of information on vaccination and

the influence that social media have on individuals’ perceptions of vaccination

The 14 studies included in this category found that social media platforms were commonly used as a source of

information for vaccination but that most of the time consulting social media had a negative influence on vaccine

uptake. Population groups in different countries were found to use social media in a variety of ways, with some

groups experiencing more positive influences from social media.

Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy TECHNICAL REPORT

2

Social media monitoring

The majority of the articles on social media monitoring were published between 2015 and 2018, and are based on

Twitter, YouTube and Facebook. Most of the studies were based on social media monitoring in relation to

vaccination generally, while some studies monitored particular vaccinations, including human papillomavirus (HPV)

and measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccination. The majority of studies involved conducting a manual search to

identify social media posts on vaccination, using the search tools available within the social media networks. The

second most commonly used method for identifying posts was the Application Programming Interfaces (APIs –

software allowing two applications to talk to each other), followed by automatic monitoring systems using

commercial software. Most of the keywords used to search for social media posts related to vaccination or vaccine-

preventable diseases, with some studies also including negative keywords, for example side effects. While many

studies only used a small number of keywords, other studies also used hashtags or longer sentences or questions.

Only a very small number of studies analysed the locations of posts, meaning that most of the studies were not

limited to one country only. In most cases, geo-localisation was performed manually, for instance by screening user

profiles, since Global Positioning System (GPS) information is not often available. Furthermore, most of the studies

looked at social media on a continuous basis, extracting data over a period of 1–3 hours and for up to 16 years.

Studies that were conducted at one specific point in time were mostly studies where a manual search had been

carried out for the data.

Sentiment analysis

1

was performed in almost all studies included in this review, with most of them conducting

manual coding of data into either positive vs. negative or pro-vaccination vs anti-vaccination sentiments. Those

that used automated systems to code sentiments mostly analysed Twitter using different tools to establish

sentiments. Some studies also included other types of content analysis, such as qualitative thematic analyses.

Finally, around half of the studies also analysed reach to understand how social media information is shared. The

studies visualised data in different ways.

Some studies provided recommendations for health authorities and health professionals on how to use social media

monitoring, in particular to start communicating on social media platforms and to use social media monitoring

findings to inform the development of intervention and communication strategies.

Social media interventions

Three types of interventions were identified: social media as a source of information about vaccination; online

group discussions and interactive websites. Most of these interventions were developed and implemented by

researchers in Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, Taiwan and the United States. Three studies evaluated existing

interventions. The effects of the interventions varied and no strong impact was identified overall. This may be due

to the methodological challenge of linking the specific effects and influence of social media to actual behaviour.

Studies measured the effect of social media interventions on knowledge and attitudes concerning vaccination, risk

perception and concerns, intentions of being vaccinated and vaccine uptake.

Discussion

While social media usage has been associated with a negative impact on public views and behaviour concerning

vaccination, it also presents many opportunities. More evidence is needed on which interventions using social

media to address vaccine hesitancy are effective in different contexts. Furthermore, while many studies have been

conducted on social media monitoring around vaccination, they have used different methodologies (e.g. use of

manual tools to retrieve data compared to APIs or automated software; manual versus automated sentiment

analyses) to obtain and analyse data, and these have not been evaluated. There is a need to evaluate different

methodological approaches to better understand what works best and to eventually provide standardised research

approaches to monitor and analyse social media. Furthermore, while the general data protection regulation (GDPR)

may limit social media monitoring to publicly available data, this also highlights the need for more control over

what happens with data collected online. It would be helpful if a code of conduct for ethical use of social media

information could be developed to ensure that those reporting on social media monitoring results adhere to fair

and responsible values.

Social media monitoring is highly dependent on what platforms have to offer in terms of APIs, geo-location data,

and sentiment analysis. To reduce the number of manual searches and analyses, and thereby improve the quality

of social media monitoring, easier ways of accessing data should be developed, whether through APIs or through

computational software. Health authorities and researchers should also reflect on the consequences for research of

the constant fluidity of online information, particularly since several platforms have decided to remove anti-

vaccination content.

1

The process of computationally identifying and categorising opinions expressed in a piece of text, especially in order to

determine whether the writer's attitude towards a particular topic, product, etc. is positive, negative, or neutral (Lexico

Dictionary, Oxford University Press)

TECHNICAL REPORT Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy

3

Finally, the purpose and value of social media monitoring should be clearly defined. While some health authorities

and researchers may try to use social media as a proxy for what the public thinks about vaccination, the reality is

often much more complex. It is unclear whether social media users are representative of the general public. Social

media monitoring should therefore be seen as a way of capturing the essence and the movement of online

discourse around vaccination in order to better understand how it can influence public perceptions and decision-

making around vaccination. Such evidence could then inform the development of targeted interventions to restore

public confidence in vaccination.

Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy TECHNICAL REPORT

4

1 Introduction

Vaccine hesitancy is increasingly being recognised as a growing problem globally. In 2019, the World Health

Organization (WHO) acknowledged that it constitutes one of the ten biggest threats to global health [2].

Confidence in vaccination is complex and influenced by an array of individual, social, and structural factors; it can

also vary depending on the vaccines and the diseases they prevent. While highly context-dependent on the one

hand, there are growing global networks promoting vaccine hesitancy, connecting across countries and

languages—aided by online translation tools and social media [3]. Vaccine refusers are a loud minority and such

clustering can interfere with the immunisation uptake required for herd protection, risking an increase in the

burden of disease [4]. Recent measles outbreaks across Europe [5-8] demonstrate the consequences of non-

vaccination and confirm recent findings that Europe is the region in the world with the least confidence in the

safety and effectiveness of vaccination [9].

Continuous advancements in communication technologies such as social media have contributed to the unmediated

spread of concerns about safety and adverse events following vaccination. New communication technologies allow

sentiments, rumours and beliefs about vaccination to quickly diffuse among networks across the world, influencing

individuals and groups online as they assess risks and benefits of vaccination [10-12]. A number of studies have

reviewed websites and social media for information on vaccination and found that it is of variable quality, with a

predominance of negative or incorrect content that influences perceptions about the risks and benefits of vaccines

[13-16].

However, social media have great potential to contribute positively to health communication by allowing direct

interactions with individuals; enhanced availability, accessibility, and customisation of information; and individual

and policy advocacy opportunities. The monitoring and measuring of content posted and shared on social media

also provides an opportunity to listen to online discourses and develop targeted, audience-focused

communications. There are some limitations to using social media for health communication, relating to quality,

confidentiality, reliability, transparency, sponsorship and privacy concerns [17,18]. Engaging on social media can

also be resource- and time-intensive for institutions, requiring radical changes in communication strategies to focus

on direct engagement with the public and provide fast and targeted responses. Social media and new

communication technologies are also rapidly evolving, and require constant adaptations to new platforms, tools

and interactions between individuals. Due to these limitations, and the important shift in communication strategies

that social media require, public health communities focussed on vaccination uptake and confidence have been

slow and inconsistent to proactively engage with and invest in social media for monitoring opinion, communicating

evidence-based information and/or countering misinformation. In the absence of a savvy, strong and sustained

public health presence, pseudoscience, confusing information and public rumour have fuelled strong anti-vaccine

sentiment and influenced vaccination decision-making through social media in countries across the world [19,20].

There are growing efforts in the field of public health and academia to better understand what is happening on

social media and how they can be used to increase vaccine confidence and mitigate concerns. ECDC commissioned

the Vaccine Confidence Project

TM

(VCP) [1] to conduct a scoping review on social media monitoring methods and

interventions around vaccination. This research project stems from the necessity to synthesise all quality research

produced to inform how social media monitoring methods and analysis can be used to understand and respond to

public discourse about vaccination on social media and to understand the uses, benefits and limitations of using

social media as an intervention tool around vaccination.

TECHNICAL REPORT Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy

5

2 Background

Social media have been defined as ‘a group of internet-based applications that build on the ideological and

technological foundations of Web 2.0, and that allow the creation and exchange of user generated content’ [21].

Web 2.0 refers to the new way in which software developers and end-users started using the World Wide Web,

where content and applications are continuously modified by all users[21]. However, when defining social media,

any given description is simply one of many and each discipline contributes its own perspective on the nature of

social media. For this scoping review, we understand social media as not just a means of communication, but also

a space where people socialise.

Prior to social media, conversations were either private or public, through broadcasting media. Social media now

allow the dissemination of conversations and opinions within a vast network without mediation, which has

contributed to the positioning of social media as a key tool to support people’s freedom of speech and expression

around the world. However, this unbounded freedom to create and share content with users around the world also

comes with major hazards, as it also facilitates the spread of unverified misinformation. This has been framed as

the ‘postmodern Pandora’s box’ of the internet; whereby data circulate unbounded, shared and re-shared

regardless of quality [22].

Virtual and in-person social interactions are deeply entwined and any definition that tries

to separate both risks inconsistency [23].

As social media are not merely a tool but a social environment in which people operate, much is said about the

various social platforms and how they account for different social spaces. However, social media should not be

seen primarily as the platforms upon which people post, but as the content posted on these platforms. Social

media users directly influence what social media are and what they will become – as seen in the recent decisions

by certain social media platforms to censor content and change algorithms to promote or reject certain content.

This also explains why social media will always be a continuously evolving environment. Recent research on social

lives online shows that it is the people using social media who create what social media mean and represent rather

than developers or social media platforms themselves. At the same time, research indicates the inability to

understand any one social media platform in isolation. The different digital platforms must be seen as relative to

each other, as people use the range of available possibilities to select specific platforms or media for particular

genres of social interaction[23].

Social media and vaccination

This new boundless information ecosystem has shaped the nature of conversations about vaccination and related

concerns. Dominant and singular narratives such as ‘vaccines are good’ are rejected, and instead vaccine-decisions

are considered ‘vaccine by vaccine, disease by disease, case by case’ [22]. In this context, facts from authorities

and experts are suspect and non-linear dialogue (dialogue that can flow in multiple ways rather than only

chronologically), is the norm [24-26]. Largescale analyses have highlighted the importance of these social networks

and trust relationships in influencing vaccine decisions [27]. As Leask et al. highlight, ‘a patient’s trust in the source

of information may be more important than what is in the information’ [28]. Rather than consulting a single,

authoritative source of information, it is more common for participants to want a variety of opinions [29].

At the same time that information is important for risk assessment and decision-making, sentiments about

vaccination can strongly affect individual and group vaccination decisions [30]. New digital media, social media in

particular, have allowed new levels of transmission of sentiments concerning vaccines [31], with negative vaccine

sentiment posts being the most liked and engaged with [32]. The rise of internet-mediated communication has

also had a significant impact on how fast rumours and unsubstantiated concerns can spread, feeding into the

abovementioned negative vaccine sentiments travelling transnationally [30].

The amplification of risk and risk perception through social media, has led some countries and health authorities to

start using social media to counter misinformation, mitigate anxiety and rebuild public trust [33]. Ireland and

Denmark have recently managed to rebuild public trust in human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination by adopting a

strategy that had social media at its core to engage parents via YouTube and Facebook. Both countries took into

consideration how information about HPV vaccination was consumed online by parents and developed their

strategies accordingly [33,34]. Another central advantage of using social media within the scope of public health

policy is the possibility to listen, in real time, to the concerns of populations and pick up signals at a very early

stage. At the same time, vaccination discourses on social media need to be understood within a digital ecosystem,

as users tend to be influenced by and use a range of social media platforms to express their feelings and beliefs.

This digital ecosystem relates to a virtual environment where a community of interacting platforms is continuously

growing and evolving which speaks to the importance of conducting social media monitoring and the valuable

insights it can bring.

As there are many ways of defining social media, for this scoping review we attempt to understand them within the

environment of public health policy and the impacts that they can have within this field. With regard to vaccination,

we understand that it is pivotal to look at the social interaction processes that may be weighing into decision-

Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy TECHNICAL REPORT

6

making and risk assessment. Kaplan et al. classify social media into blogs, collaborative projects (e.g. Wikipedia),

social networking sites (e.g. Facebook), content communities (e.g. YouTube), virtual social worlds (e.g. Second

Life), and virtual game worlds (e.g. World of Warcraft) [21].

Since we define social media in this report as online environments with a strong interaction component as their

main purpose

,

we have made the methodological decision to focus on social networking sites and content

communities. We have chosen to exclude online platforms that did not have social interactions as their main

purpose, even though they had some scope for user interaction (e.g. blogs and websites with comments sections).

TECHNICAL REPORT Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy

7

3 Goals and objectives

The aim of this scoping review was to systematically map, analyse and summarise knowledge and research on

social media and vaccination and to identify examples of how information collected can inform communication and

interventions to address vaccine hesitancy. We provide an overview of how social media monitoring and analysis of

vaccination can support those working in public health agencies and immunisation programmes by looking at the

type of social media data to collect, how social media data can be analysed and interpreted, and what types of

intervention can be developed based on data collected to increase vaccine confidence and increase vaccination.

The specific objectives of the systematic scoping review were to:

• identify individuals’ preferences for using different social media platforms as a source of information on

vaccination and the influence that social media has on individuals’ perceptions of vaccination;

• identify different social media monitoring methods and tools in the context of vaccination and their

strengths and weaknesses;

• review how social media monitoring methods and information gathered from the monitoring can be used to

inform communication strategies;

• identify the uses, benefits and limitations of social media as an intervention tool in relation to vaccination

(i.e. how effective social media is as an intervention tool for increasing vaccination).

Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy TECHNICAL REPORT

8

4. Review methods

Systematic scoping reviews are a relatively new method for mapping existing literature in a given field. Systematic

scoping reviews have been used to ‘clarify working definitions and conceptual boundaries of a topic or field’ and

have been particularly useful as an exploration tool for large, complex and heterogeneous topics usually not

suitable for systematic literature reviews [35,36]. While systematic literature reviews are often focused on

establishing the effectiveness of interventions, systematic scoping reviews take a broader approach and aim to

map international literature or to identify how research has been conducted [35]. For these reasons, it was decided

to conduct a systematic scoping review to address the aims of this study and to summarise methodologies that

have been used to monitor social media in relation to vaccination. The methodology used to conduct this study, as

described below, was based on the work provided by Arksey et.al. and further developed by the Joanna Briggs

Institute [35-37].

4.1. Search strategy and database search

Librarians at ECDC developed the search strategy, balancing feasibility and comprehensiveness and including a mix

of social media and vaccine keywords. The search strategy was developed for use in Embase, and adapted for use

in PubMed, and Scopus by ECDC and in Medline, PsycINFO, PubPsych, Open Grey (grey literature), and Web of

Science (grey literature) by the VCP and is available in Annex 8.1. Librarians at ECDC peer-reviewed the final

search strategies for all databases.

One researcher from the VCP conducted the search in all databases in December 2018 and exported all articles

into Endnote. Duplicates were then removed in accordance with guidelines provided by ECDC.

4.2. Screening and selection of articles

Two reviewers independently screened articles included in the Endnote file by title and abstract, according to a set

of inclusion and exclusion criteria:

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for screening of articles

Inclusion criteria

Exclusion

• Study settings: no restrictions

•

Not about vaccines, or not about human vaccines (i.e.

vaccines for animals)

• Research topics: articles were included if they studied

the following topics: methods of social media

monitoring around vaccination, use of social media

monitoring to address vaccine hesitancy, use of social

media interventions to address vaccine hesitancy

(knowledge, hesitancy, confidence, awareness or

coverage)

•

Articles with studies focusing on:

− Other types of media (not social media) or online

resources

− Articles that only use social media to recruit study

participants

• Publication years: From 2000 (incl.), to include all

studies conducted on social media monitoring

•

Publication types:

− Conference abstracts, editorials, commentaries,

letters to the editors

• Location: global

• Types of studies

− Efficacy trials, pre-clinical trial research

− Safety research

− Serologic investigations, immunogenicity studies

− Health economic studies

• Languages: The VCP extracted data from and analysed

articles in English, Spanish, and Italian.

• Vaccines: Human vaccines

• Study design: quantitative and qualitative studies,

observational and interventional studies

• In this review, social media included: social networking

sites and content communities (e.g. Facebook, Twitter,

LinkedIn, Instagram, Snapchat, YouTube, Vimeo,

Reddit, Quora, online discussion forums, or Pinterest).

After articles were selected through title and abstract screening, the two reviewers proceeded to full text screening

to confirm the final list of included studies. All disagreements between the reviewers were resolved by discussion.

A summary of the search and selection process are provided with a PRISMA chart (see Figure 1).

TECHNICAL REPORT Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy

9

4.3. Data extraction and analysis

During the full text article selection, articles were divided into three categories corresponding to the various objectives

described above: articles describing individuals’ preferences for using different social media platforms as a source of

information on vaccination and the influence that social media have on individuals’ perceptions of vaccination, social

media monitoring articles and articles describing social media interventions to address vaccine hesitancy.

Three researchers from the VCP extracted data into an Excel spreadsheet for these three categories of articles, as

per the information presented in Table 1.

Table 2. Data extraction categories

Social media monitoring articles

User preferences articles and

interventions articles

• Author/reference

• Year of publication and study

• Country of study

• Aims/purpose of study

• Study population and sample size

• Setting

• Vaccine

• Type of social media

• Tool for data collection and details

• Keywords selection and exclusion criteria

• Sentiment coding and analysis

• Geo-location of data

• Reach, spread and interaction

• Visualisation of data

• Other types of analyses

• Number of posts and results

• Public health implications

• How to use social media monitoring, in particularly to

start communicating on social media platforms.

• Limitations

• Author/reference

• Year of publication and study

• Country of study

• Aims/purpose of study

• Study population and sample size

• Setting

• Vaccine

• Type of social media

• Methodology

• Intervention type and details

• Duration of intervention

• Outcomes and details

• Key findings

• Limitations

Four researchers then summarised, charted and analysed the data extracted. The analysis of the included articles

was mainly descriptive (see more details on the analysis conducted for each of the three types of articles below),

as articles were heterogeneous and presented highly diverse purposes, methodologies and study outcomes.

Preferences for use of social media platforms as a source of information on vaccination and the

influence that social media have on individuals’ perceptions of vaccination

Articles about individual preferences regarding social media were analysed by looking at the use of social media to

gain or share information on vaccines and the possible influence of social media on vaccine attitudes and/or

uptake. Results were noted, and the proportion of participants either using social media or being influenced by

social media were listed for each study and then described in the report.

Media monitoring analysis

When analysing the media monitoring articles the key focus was to describe methodologies used in different studies to

monitor social media and their evaluation (if applicable). The researchers therefore provided a descriptive analysis of the

type of data collection tools used to gather data from social media, the keywords and search strategies used (including

duration of search), and the various analytical methods (sentiment or content analysis, analysis of spread, reach and

interaction, and geo-location of data). Data was first extracted to an Excel spreadsheet in accordance with the categories

in Table 1; this allowed reviewers to compare results across all studies, list and identify the frequency of different

methods used for social media monitoring in different studies, and identify common themes. Two reviewers met to

discuss the extraction spreadsheet, the themes identified and the findings of this review.

Suggestions from the studies on how social media monitoring can inform vaccination communication strategies

were also included.

Intervention articles

For the intervention articles, the data were first categorised by type of intervention. The VCP then recorded results

for various study outcomes to provide a clear overview of the effects of the various interventions. For qualitative

studies, a list of key themes was compiled and analysed. Some descriptive information was also provided, such as

the number of studies reporting different types of interventions or conducted with different population groups; the

names of social media platforms used most frequently by different population groups; or the methods used for

monitoring social media platforms around vaccination.

Some analyses were also common to all three categories, such as the types of social media described, the type of

vaccines studied, and the number of articles published over time, to reflect how much attention the topic has

received in recent years.

Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy TECHNICAL REPORT

10

5. Review results

The search across all databases generated 15 435 articles, from which 7 539 duplicates were excluded (see Figure

1 for PRISMA chart). The remaining 7 896 unique articles were screened by title and abstract using the inclusion

and exclusion criteria listed above. A total of 7 628 articles were excluded, leaving 268 articles for full text review.

From these, 153 articles were excluded (see annexes detailing reasons for exclusion) for the following reasons:

article on media but not social media monitoring (n=96), no data provided in the article (n=19), about websites or

mobile apps but not social media (n=26), conference abstracts or editorials/letters to the editors (n=6), article

containing data already published in another included article (n=1), article not looking at vaccination (n=1).

Additionally, the full text of four articles on social media monitoring was not accessible, even after making enquiries

with multiple libraries.

At the end of the screening process, a total of 115 articles was included for analysis:

• 13 articles looking at individuals’ preferences for using social media as a source for vaccination information

and the influence that social media have on individuals’ perceptions of vaccination,

• 85 articles on social media monitoring,

• 15 articles on social media as an intervention tool around vaccination,

• one article that looked at both an intervention and individuals’ preferences for using social media as a

source for vaccination information,

• one article that combined social media monitoring and a social media intervention.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram

TECHNICAL REPORT Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy

11

5.1 Individuals’ preferences for using social media platforms

as a source of information on vaccination and social media’s

influence on individuals’ perceptions of vaccination

A total of 14 articles explored individuals’ preferences for receiving information via social media, which social media

platforms are used and how information shared on social media influences the perceptions of vaccination. Annex 8.2

provides an overview of the studies relating to the use of social media to gain or share information about vaccines and

the possible influence of social media on vaccine attitudes and/or uptake.

5.1.1 Preferences regarding the use of social media as a source of

information on vaccination

Several studies pointed to social media as a source of health-related information:

• Five out of seven parents in one US study US cited social media as a common resource for information [38].

• Another study in the US found that 62% of adults questioned used Facebook to find information on the

influenza vaccine, compared to 15% for Twitter [39].

• In a survey of undergraduate students in Seoul, South Korea 30% of the respondents cited social media as

a source for information on HPV [40].

• In the UK, a study found that in a group of 626 parents who used the Internet to find information about

vaccinations, 13% used Facebook or Twitter and 6% used discussion forums [41].

• Another study in the UK focused on pregnant women using social media and found that 21% of the

participants used social media to find information on vaccinations during their pregnancy, with Facebook

and WhatsApp being the most popular platforms [42].

Limited use of social media as a source of information

• A Canadian study found that 68% of participating medical students had never used social networking sites

such as Facebook or MySpace to obtain health-related information [43].

• Similarly, university student participants in a study in Northern Ireland reported social media to be their least

preferred source of information on awareness of meningitis and vaccines [44].

• A dissertation from the US reported that although 66% of parents had seen information about HPV vaccination

on social media, only 4% had actively used social media as their main source of information about HPV

vaccination (a lower percentage than those using information from friends and government health

organisations) [45].

• A US study found that 11% of parents who had heard HPV vaccine stories found them on social media and these

accounts were more likely to be negative ‘stories of harm’ than content through other information channels [46].

• Regarding overall use of social media, a study conducted among medical students in Canada found that while

66% of participants sometimes or often used YouTube, 24% reported sometimes looking for health-related

information on the platform, and only 2% reported always doing so [43]. Furthermore, 42% reported using

YouTube for health purposes, including educational purposes, but 17% were uncertain about the platform’s

trustworthiness and 36% reported minimal trust in health content provided on YouTube [43].

Willingness to share information on social media

• None of the female students in one study on a university campus in the United States shared HPV information

on Facebook, 71% of them were willing to do so in the future [47].

• One Spanish study also looked at the willingness of medical students to use/follow/participate in Facebook

pages promoting influenza vaccination. They found that 63% of students would accept an invitation to follow a

Facebook page with formal or technical content on the healthcare worker influenza vaccination campaign,

while 65% would accept an invitation to follow a Facebook page that communicated the same information

informally (such as animations or offbeat news) [48]. In all, 19% of the students would actively participate in

a ‘technical’ Facebook page, compared to 28% of students who would actively participate in an ‘informal’

Facebook page [48].

Key messages

Preferences regarding the use of social media as a source of information on vaccination:

• Between 4 and 62% of various study populations in different countries use social media as a source

of information on vaccination, with results varying by type of social media platform.

• Overall Facebook was the most common social media resource for information on vaccination.

Social media users’ perceptions of vaccination:

• Most studies suggest a negative relationship between social media use and vaccination uptake and

attitudes, which could sometimes be explained by the important presence of negative content

concerning vaccination online.

Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy TECHNICAL REPORT

12

5.1.2 Social media as an influence on perceptions of vaccination

Several studies considered not only individuals’ preferences for social media use but also how this usage influenced

their perceptions of vaccination, such as their attitudes and/or uptake of vaccination. Most of these studies

suggested a negative relationship between various social media use and vaccination uptake, while others

suggested the potential for the positive influence of social media on vaccination uptake. Seven of these specifically

referred to Facebook, four referred to Twitter and seven did not specify a social media network or platform.

Negative relationship between social media and vaccination attitude and/or

uptake:

• A study in the UK that asked pregnant or recently pregnant women how they searched for information on

vaccinations during pregnancy found that 12% of participants believed the information they found on social

media influenced their vaccination decisions [42]. This influence manifested in a significantly negative

relationship in relation to pertussis vaccination, with women who used social media to gather information

being 58% less likely to receive this vaccination during pregnancy[42].

• Another study in the UK reported that parents who used social media, such as discussion forums and

Facebook or Twitter, were more likely to report that they had come across some material that made them

doubt vaccinations (31% of parents who used discussion rooms and 23% of parents who used Facebook or

Twitter versus 8% of all participating parents) [41].

• Similarly, three studies in the US found social media had a negative influence on parents’ perceptions of

vaccines [49] [45]. In one of these studies, 10% of the participating parents and guardians felt that social

media increased their sentiments of fear around the HPV vaccination [45].

• Another study about the HPV vaccine conducted in Seoul reported that undergraduate students felt the

information they obtained about the vaccine via social media increased their perception of barriers to

receiving it [40].

• In the UK, a study considered social media as one of the various intervention strategies used to increase

influenza vaccine uptake in healthcare workers over the course of four years. The researchers in this study

reported a significantly reduced vaccination uptake when using promotions on Facebook (22%) and Twitter

(24%) as an intervention, although no reflection on the reason for these results was provided [50].

• In India, a study was conducted to assess the influence on trust of a large measles-rubella vaccination

campaign in the southern state of Tamil Nadu. This study found that most parents who rejected the vaccine

for their children also placed higher levels of trust in social media platforms, including WhatsApp[51].

Positive relationship between social media and vaccination attitude and/or uptake

• A study on vaccines during pregnancy in the UK found that women who used WhatsApp and LinkedIn were

more likely to receive both the influenza and pertussis vaccines while pregnant [42].

• A study in the US found that participants who used Facebook or Twitter as sources of health information

were more likely to be vaccinated [39].

• Participants from another study in the United States proposed using social media to circulate positive

messaging about the HPV vaccine [38].

5.2 Social media monitoring

There is a growing body of literature describing social media monitoring methods. For this report the results of the

social media monitoring are organised into three major phases (see Figure 2): 1- preparation, 2- data extraction

and 3- data analysis.

Figure 2. Social media monitoring phases

TECHNICAL REPORT Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy

13

Articles on social media monitoring in this review were therefore reviewed in accordance with the following three

phases:

1. Preparation:

• Characteristics of the studies in this report - purpose of social media monitoring and platforms monitored

• Ethics approval

2. Data extraction:

• Data extraction tools

• Period of monitoring

• Search strategies

• Visualisation of data

3. Data analysis:

• Geo-localisation

• Reach

• Trends, content and sentiments

5.2.1 Preparation

Study characteristics

A total of 86 articles monitored and analysed social media in relation to vaccination (see Annex 8.3 for a table

summarising the characteristics and methods used in these articles). While the first study was published in 2006,

only a very small number of studies were published between 2006 and 2014. In 2015, the number of published

articles about social media monitoring increased substantially, with 83% of all articles identified in this review

published since 2015. Nine studies were published in 2015 (11%), 14 in 2016 (16%), 25 in 2017 (29%) and 21 in

2018 (24%). As the search was conducted in December 2018, only two articles, available ahead of print, were

identified for 2019.

Purpose of social media monitoring

It is important to establish the purpose of analysing social media information on vaccination as this will influence

how and which data are collected. For the majority of studies (55/86, 64%) the goal was to increase

understanding of how vaccination is portrayed on social media, through online discourse, sentiment or the way in

which information is produced, engaged with and shared. Other aims included monitoring the reaction after an

outbreak, monitoring the impact of a campaign or intervention or a vaccination programme, monitoring

misinformation or monitoring public concerns and questions.

Key messages

• In 2015, the number of articles published on social media monitoring increased substantially, with

83% of all articles identified in this review published since 2015.

• The large increase in the number of articles from 2015 was mostly attributed to an increase in studies

conducted on Twitter.

Purpose

• The purpose of analysing information about vaccination online will influence how and which data are

collected. Different purposes were identified:

− increasing understanding of how vaccination is portrayed on social media through online

discourse, sentiment or how information is produced, shared and engaged with;

− monitoring the reaction after an outbreak;

− monitoring the impact of a campaign or intervention or a vaccination programme;

− monitoring misinformation;

− monitoring public concerns and questions in general or over time.

Types of social media

• A large majority of studies focused on Twitter, followed by YouTube, Facebook and various online

forums.

Ethics

• The questions relating to ethics approval to perform social media monitoring research are growing. In

addition, a number of studies raised the issue of posts not being publically available.

• Out of the 86 articles on social media monitoring, only 13 (15%) explicitly mentioned having received

approval from an institutional ethics review board. Some of the other studies considered that they

were exempt from institutional/ethical review as their studies did not directly involve human subjects

or because social media analysis only included publically available data.

• Other researchers believe that anonymization is not enough and they urge that other solutions should

be found due to the fact that private data can easily be revealed.

Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy TECHNICAL REPORT

14

Type of social media monitored

A large majority of studies focused on Twitter (n=42)[30,52-92], followed by YouTube (n=12)[32,93-103],

Facebook (n=11)[45,104-113], and various online forums (n=9)[114-122]. The forums included in the studies

reviewed in this report were babytree (China), Iltalehti and KaksPlus (Finland), Mothering.com (UK), and Mumsnet

(UK). Additionally, five studies either used multiple forums from the same country identified by a Google search,

forums specifically designed for a particular event or study, or failed to name the forum analysed. Other types of

social media monitored included Yahoo! Answers (n=2)[123,124], Pinterest (n=1)[125], Reddit (n=1)[126], and

Weibo (n=1)[127]. An additional seven studies monitored a mix of social media networks, including Digg, Hyves,

Facebook, unspecified forums, LinkedIn, Reddit, Twitter, and YouTube[128-134]. A description of all the different

social media platforms monitored across the 86 studies is provided in Table 3.

Table 3. Description of the social media platforms identified in the scoping review

Digg

Platform allowing users to post, save and share news stories and to vote content up or down.

Facebook

Platform used for social networking, allowing users to create profiles with personal information

about themselves, and to post, interact, comment or share messages, photos, videos and

other media content with other members (friends or followers). The platform also allows

groups and professional pages to be created, with comments, likes and shares of these posts

across both personal profiles and group/pages (depending on privacy settings).

Forums

Type of social media platforms allowing users to write content in message boards or online

discussion sites/threads. The forums included in the studies reviewed in this report were

babytree (China), Iltalehti and KaksPlus (Finland), Mothering.com (UK), and Mumsnet (UK).

Hyves

Platform used for social networking, allowing users to interact with other members (Dutch

equivalent of Facebook, discontinued in 2013).

LinkedIn

Platform used for professional networking and for posting jobs and/or curriculum vitae or

sharing content in the form of short messages, images, videos or links.

Pinterest

Platform for posting, interacting with and sharing images/articles, referred to as pins, as well

as videos and other media content.

Reddit

Platform for posting links, text messages, videos and images. These are then voted up or

down and discussed by other members.

Twitter

Platform for posting, interacting with and sharing short messages (tweets) of maximum 280

characters, video and/or links.

Weibo

Platform for posting, interacting with and sharing short messages (Chinese equivalent of

Twitter).

YouTube

Platform for posting, interacting with and sharing videos and blog posts.

Figure 3 shows the number of articles identified by year and by type of social media (excluding the two 2019

articles). It indicates that the large increase in the number of articles from 2015 was mostly attributed to an

increase in studies conducted on Twitter (n=37, 54% of all articles published between 2015 and 2018), and to a

smaller extent Facebook (n=10, 15%). Articles about less commonly studied types of social media (Pinterest,

Weibo, Reddit, and Yahoo! Answers) were all published after 2015.

TECHNICAL REPORT Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy

15

Figure 3. Number of articles published by type of social media and by year until 2018

Note: Forum refers to the different forums included in the articles covered by this report: babytree (China), Iltalehti and KaksPlus

(Finland), Mothering.com (UK), and Mumsnet (UK)

Type of vaccine monitored

Most of the articles identified in this review looked at vaccines in general (40%, n=34) [32,55-57,59-

61,68,72,78,81,83,87,89,90,95,97,98,101,103-107,110-113,118,121,122,125,126,132], HPV vaccination (27%, n=23)

[45,58,63-66,69,70,73-75,82,84,86,92-94,96,99,102,117,123,130] or measles vaccination (14%, n=12)

[52,62,77,80,85,88,91,116,119,129,131,133] (Figure 4). Additionally, five studies monitored social media in relation to

the 2009 A(H1N1) influenza pandemic [30,76,114,120,128] and four studies looked at seasonal influenza

[67,71,124,134]. Other vaccines monitored on social media included polio (n=2) [108,109], diphtheria (n=1) [79],

hepatitis B (n=1) [127], meningococcal B (n=1) [100], pentavalent DTP-HepB-Hib (n=1) [54], and rotavirus (n=1)

[115]. One study also looked both at polio and HPV vaccination [53].

Figure 4. Number of articles published by type of vaccine

Countries monitored

A large proportion of studies did not restrict monitoring to one specific country and therefore contained global results

(n=41) [52-57,59,62-65,67,70-75,77,78,80,81,84,86,90,92-95,97,99-105,110,125,126] (Figure 5). However, some of

these studies have restricted their search to specific languages such as English or Spanish, which may therefore provide

skewed results towards particular regions of the world. Fifteen studies were conducted specifically with data coming from

the United States (US) [30,45,58,61,66,68,83,85,87,88,91,96,107,129,130], seven from Italy [32,60,89,98,106,118,133],

three from the Netherlands [69,131,134] and three from the United Kingdom (UK) [76,116,122]. Other countries

specifically monitored included Canada (n=2) [113,128], China (n=2) [115,127], Israel (n=2) [108,109], Spain (n=2)

[79,114], Australia (n=1) [119], Chile (n=1) [123], Finland (n=1) [120], Japan (n=1) [124], and Romania (n=1) [117].

Four studies looked at data from multiple countries, including Australia, the US, Canada, and the UK [82,111,121,132].

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

2006 2007 2008 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

NUMBER OF ARTICLES PUBLISHED

YEAR

Forum Youtube Facebook Twitter Mix Pinterest Weibo Reddit Yahoo Answers

1

1

1

1

1

1

2

4

5

12

23

34

Diphtheria

Hepatitis B

Meningococcal B

Pentavalent

Rotavirus

Polio and HPV

Polio

Seasonal influenza

Pandemic influenza (H1N1)

Measles

HPV

Vaccination in general

Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy TECHNICAL REPORT

16

Figure 5. Number of articles published by country monitored

Ethics approval - public versus private data

The issue of posts not being publically available was raised in nine studies, either as a pre-defined exclusion

criterion or as a limitation [45,53,69,80,87,108,111,121,133]. This could be linked to certain ethical issues.

• Out of the 86 articles on social media monitoring, only 13 (15%) explicitly mentioned having received

approval from an institutional ethics review board in Australia, Canada, Israel, Romania, the UK and the US

[45,58,62-64,76,82,92,105,108,109,113,117].

• Additionally, one study did not mention whether they had received ethics approval, but stated ‘guidelines

from the Institutional Review Board have been considered and applied to protect the identity of forum

users’ [115].

• Nine studies also specifically stated that they were exempt from institutional/ethical review as their studies

did not directly involve human subjects or because social media analysis only included publically available

data [56,57,70,74,86,94,95,99,104].

• The authors of a study that obtained ethical approval, conducted on Facebook in Israel, further explained

that as they anonymised their data, participant consent was not required as conversations on the Internet

happen in public fora, where ‘subjects would expect to be observed by strangers’ [108].

• However, anonymisation was not enough for the authors of a global study conducted on Twitter, who were keen

for other solutions to be found. They explained that private data could easily be revealed ‘through the integrative

analysis of multiple datasets’ and that revealing the identity of social network contributors who may have wished

for it to be kept secret was feasible (the study did not mention seeking ethical approval) [80].

• Finally, Tangherlini et al, who analysed comments on forums in the US and Canada (but did not mention

seeking ethical approval) raised the growing challenge of accessing data on social media, as corporations

are constantly reducing access to data [121].

1

1

1

1

1

2

2

2

2

3

3

4

7

15

41

Australia

Chile

Finland

Japan

Romania

Canada

China

Israel

Spain

Netherlands

United Kingdom

Mix of countries

Italy

United States

Global/not specified

TECHNICAL REPORT Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy

17

5.2.2 Data extraction

Data extraction tools

In order to collect data from social media on the subject of vaccination, the studies in this review used:

• Manual browser searches on web browsers such as Firefox, and Google Chrome. Browser searches are

performed from within social media platforms – e.g. the basic or advanced search bar usually found at the

top of the page on Twitter, YouTube or Facebook.

• Social media APIs (Application Programming Interfaces). The term ‘API’ refers to a software intermediary

that allows two applications to talk to each other. When Twitter is used, the Twitter application connects to

the Internet and sends data (e.g. the text or images posted with a tweet) to a server. The server then

retrieves the data, interprets it, performs the necessary actions and sends it back to the Twitter application

on a user's phone, web browser or a researcher's database, which is then interpreted and shown to the

user in a readable format. APIs work across all social media platforms to pull and interpret data from

servers storing information for Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Reddit and many more.

• Automatic monitoring (commercial software). These can be automated web platforms that are free, open

source (open to development from other developers), or commercial (where access is allowed via a

subscription pricing structure);

• Use of both manual searches and APIs.

• Use of both automatic software and APIs.

Figure 6 shows the number of software tools used within each category.

Figure 6. Number of studies by type of social media monitoring tools used

Notes to the figure:

API – Social media Application Programming Interfaces

Manual - Manual browser searches on web browsers

Automatic or commercial tool - Automated web platforms.

Manual browser searches

A total of 36 studies used web-based manual tools. Studies that used manual browser search functions within

social media platforms tended to collect less data than those accessing the automatic Application Programming

Interfaces (APIs) or software. Some of the limitations of manual browser searches are described in Table 4.

35

20

24

6

1

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40

NUMBER OF ARTICLES PUBLISHED

API and Manual

API and Automatic

API

Automatic or commercial

tool

Manual

Key messages

• Studies that used manual browser search functions within social media platforms tended to collect

less data than those accessing the automatic Application Programming Interfaces (APIs) or other

software.

• A large number of studies used the Twitter API to collect data due to the ease of access given by the

Twitter platform to its data stream compared to other platforms.

• Studies used a range of commercial software, with the majority accessing paid-for periodical and

historical Twitter data.

Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy TECHNICAL REPORT

18

Table 4. Different manual browser searches and their limitations mentioned by the studies using the tool

Social media tool

Limitations

YouTube search browser

[32,93-103]

• Despite the use of a variety of search terms being seen as a strength of the study, only

the top 50 hits according to relevance were chosen to be analysed (this is in the context

of the three million videos posted on the topic of vaccines currently on YouTube at the

time of the project)[96]

Facebook search tool

[45,104,105,108,109,112,113]

• Due to the time intensity that assessing each Facebook site required, it was impractical

to analyse each site in detail. Another limitation mentioned was that the focus of the

assessment was on the most recent posts. The nature of posts on Facebook sites may

change as new information regarding vaccines reaches the general public, such as

during flu season or when school starts, and parents must turn in their child’s

vaccination records. During the short time for the data collection, there was no major

news related to vaccines that had recently been reaching the general public. Finally, the

authors did not gather data regarding individual users and cannot determine whether

activity on the site centred on several engaged users or was spread among site

membership [104]

• A small limitation to using a Hypertext PreProcessor (PHP) script supplied by Facebook

as an add-on to the basic Facebook search tool as the script served to only collect each

post’s first 25 comments - this meant that not all comments for every post were

analysed. However, it was not considered a strong limitation since each post or

comment was analysed as an individual unit. From the sampling frame, a sample of

2 289 items were randomly selected using a ‘randomise numbers’ command. This was

considered a representative sample of the initial sampling frame. This study was made

before the data protection ethics and protocols linked to the 2018 General Data

Protection Regulation (GDPR) rules came into place[135], although all the data were

anonymised and available for scientific use, the authors acknowledged that this

methodology may give rise to ethical concerns, given that identifiable comments made

by people on public Facebook pages are scrutinised. Nevertheless, at the time of the

study (2016), according to the Codes of Ethics and Conduct of Internet Research[136],

if an observation of public behaviour takes place in public fora where subjects would

expect to be observed by strangers (such as an open Facebook discussion), explicit

individual consent is not required. If this search was made today, however, the analysis

of potential identifiable user posts on Facebook would be limited[109].

• Luisi (2018)[45], found that the Facebook search feature does not allow users to

organise results by date or engagement (e.g. likes/comments). This limits flexibility in

data collection. Technology also limited the ability to archive Facebook posts. When

loading the search results, one would have to scroll down to make the area printable.

Scrolling down too far would cause internet browsers to crash. Moreover, this study only

collected public Facebook content in an effort to only analyse content that would be

available to any Facebook user, because access to private social media feeds is not

possible without specific participant consent.

• Suragh et al. (2018)[112], found that a limitation of just using the Facebook browser

search tool was the inability to examine entire social networks, which means that the

fraction represented by the study data of what actually exists is unknown. The study

was also limited to the information included in the online reports, with potential biases

and errors in reporting. Lastly, there was the challenge of conducting searches in

different countries. The findings from the Google and Facebook searches were

dependent upon the geographic location of the reviewer and this reflected on targeting

‘popular’ findings according to the search location and specific algorithms used by these

companies. This limitation could have also been a result of the study methodology,

which only included reports found in the first three pages for Google and top 20 posts

for Facebook. It is possible that if larger search samples (Google produced hundreds of

thousands of URL (Uniform Resource Locator) links per search term) were analysed,

both reviewers would have found exactly the same results. Facebook results were

dependent on the date and time of the search (e.g. the highest placed posts found on

one day were not the same as those found the next day) therefore searches had to be

completed in one sitting and some of the URL links identified in Facebook did not work.

The study used standardised search terms but other reports of cluster immunisation

may probably have been found by including additional search terms and expanding to

different languages, countries and regions.

TECHNICAL REPORT Systematic scoping review on social media monitoring methods and interventions relating to vaccine hesitancy

19

Social media tool

Limitations

Forum search tools[116].

• In one study by Skea (2006)[116] relating to internet forum discussion on the measles-

mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine, one limitation found was that the 617 messages

analysed were those posted to only one website, which meant that participants were

probably not demographically representative of the wider population. In addition, a

higher proportion of participants in the fora had refused MMR vaccine than in the