National Model EMS

Clinical Guidelines

March 2022

VERSION 3.0

These guidelines will be maintained by the National Association of

State EMS Officials (NASEMSO) to facilitate the creation of state

and local EMS system clinical guidelines, protocols, or operating

procedures. System medical directors and other leaders are

invited to harvest content as will be useful. These guidelines are

either evidence-based or consensus-based and have been

formatted for use by field EMS professionals.

NASEMSO Medical Directors Council

www.nasemso.org

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

Rev. March 2022

2

Version 3.0

Contents

INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 6

PURPOSE AND NOTES ........................................................................................................... 7

TARGET AUDIENCE .................................................................................................................. 8

WHAT IS NEW IN THE 2022 EDITION ........................................................................................... 8

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................. 8

UNIVERSAL CARE ................................................................................................................... 9

UNIVERSAL CARE GUIDELINE ..................................................................................................... 9

FUNCTIONAL NEEDS .............................................................................................................. 19

PATIENT REFUSALS ................................................................................................................ 23

CARDIOVASCULAR .............................................................................................................. 26

ADULT AND PEDIATRIC SYNCOPE AND NEAR SYNCOPE .................................................................... 26

CHEST PAIN/ACUTE CORONARY SYNDROME (ACS)/ST-SEGMENT ELEVATION MYOCARDIAL INFARCTION (STEMI)

........................................................................................................................................ 31

BRADYCARDIA ..................................................................................................................... 35

IMPLANTABLE VENTRICULAR ASSIST DEVICES ............................................................................... 39

TACHYCARDIA WITH A PULSE ................................................................................................... 42

SUSPECTED STROKE/TRANSIENT ISCHEMIC ATTACK ........................................................................ 48

GENERAL MEDICAL .............................................................................................................. 51

ABDOMINAL PAIN ................................................................................................................ 51

ABUSE AND MALTREATMENT ................................................................................................... 55

AGITATED OR VIOLENT PATIENT/BEHAVIORAL EMERGENCY ............................................................. 59

ANAPHYLAXIS AND ALLERGIC REACTION ..................................................................................... 66

ALTERED MENTAL STATUS ...................................................................................................... 71

BACK PAIN ......................................................................................................................... 75

END-OF-LIFE CARE/HOSPICE CARE ............................................................................................ 78

HYPERGLYCEMIA .................................................................................................................. 81

HYPOGLYCEMIA ................................................................................................................... 84

NAUSEA-VOMITING .............................................................................................................. 89

PAIN MANAGEMENT ............................................................................................................. 93

SEIZURES .......................................................................................................................... 101

SHOCK ............................................................................................................................. 107

SICKLE CELL PAIN CRISIS ....................................................................................................... 114

RESUSCITATION ................................................................................................................ 117

CARDIAC ARREST (VF/VT/ASYSTOLE/PEA).............................................................................. 117

ADULT POST-ROSC (RETURN OF SPONTANEOUS CIRCULATION) CARE .............................................. 126

DETERMINATION OF DEATH/WITHHOLDING RESUSCITATIVE EFFORTS ............................................... 130

DO NOT RESUSCITATE STATUS/ADVANCE DIRECTIVES/HEALTHCARE POWER OF ATTORNEY (POA) STATUS 133

TERMINATION OF RESUSCITATIVE EFFORTS ................................................................................ 136

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

Rev. March 2022

3

Version 3.0

RESUSCITATION IN TRAUMATIC CARDIAC ARREST ........................................................................ 141

PEDIATRIC-SPECIFIC GUIDELINES ....................................................................................... 144

BRIEF RESOLVED UNEXPLAINED EVENT (BRUE) & ACUTE EVENTS IN INFANTS .................................... 144

PEDIATRIC RESPIRATORY DISTRESS (BRONCHIOLITIS) .................................................................... 150

PEDIATRIC RESPIRATORY DISTRESS (CROUP) .............................................................................. 155

NEONATAL RESUSCITATION ................................................................................................... 159

OB/GYN ............................................................................................................................ 165

CHILDBIRTH....................................................................................................................... 165

ECLAMPSIA/PRE-ECLAMPSIA ................................................................................................. 171

OBSTETRICAL AND GYNECOLOGICAL CONDITIONS ........................................................................ 175

RESPIRATORY .................................................................................................................... 178

AIRWAY MANAGEMENT ....................................................................................................... 178

RESPIRATORY DISTRESS (INCLUDES BRONCHOSPASM, PULMONARY EDEMA) ...................................... 190

MECHANICAL VENTILATION (INVASIVE) .................................................................................... 198

TRACHEOSTOMY MANAGEMENT ............................................................................................. 203

TRAUMA ........................................................................................................................... 208

GENERAL TRAUMA MANAGEMENT .......................................................................................... 208

BLAST INJURIES .................................................................................................................. 215

BURNS ............................................................................................................................. 218

CRUSH INJURY/CRUSH SYNDROME .......................................................................................... 222

EXTREMITY TRAUMA/EXTERNAL HEMORRHAGE MANAGEMENT...................................................... 225

FACIAL/DENTAL TRAUMA ..................................................................................................... 230

HEAD INJURY..................................................................................................................... 233

HIGH THREAT CONSIDERATIONS/ACTIVE SHOOTER SCENARIO ........................................................ 238

SPINAL CARE ..................................................................................................................... 241

TRAUMA MASS CASUALTY INCIDENT ....................................................................................... 249

TOXINS AND ENVIRONMENTAL ......................................................................................... 252

POISONING/OVERDOSE UNIVERSAL CARE ................................................................................. 252

ACETYLCHOLINESTERASE INHIBITORS (CARBAMATES, NERVE AGENTS, ORGANOPHOSPHATES) EXPOSURE ... 260

RADIATION EXPOSURE ......................................................................................................... 271

TOPICAL CHEMICAL BURN ..................................................................................................... 275

STIMULANT POISONING/OVERDOSE ........................................................................................ 279

CYANIDE EXPOSURE ............................................................................................................ 283

BETA BLOCKER POISONING/OVERDOSE .................................................................................... 287

BITES AND ENVENOMATION .................................................................................................. 291

CALCIUM CHANNEL BLOCKER POISONING/OVERDOSE .................................................................. 295

OPIOID POISONING/OVERDOSE ............................................................................................. 303

AIRWAY RESPIRATORY IRRITANTS ........................................................................................... 308

RIOT CONTROL AGENTS ....................................................................................................... 317

HYPERTHERMIA/HEAT EXPOSURE ........................................................................................... 320

HYPOTHERMIA/COLD EXPOSURE ............................................................................................ 326

DROWNING ...................................................................................................................... 333

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

Rev. March 2022

4

Version 3.0

DIVE (SCUBA) INJURY/ACCIDENTS......................................................................................... 337

ALTITUDE ILLNESS ............................................................................................................... 341

CONDUCTED ELECTRICAL WEAPON INJURY (I.E., TASER®) ............................................................ 345

ELECTRICAL INJURIES ........................................................................................................... 348

LIGHTNING/LIGHTNING STRIKE INJURY ..................................................................................... 352

APPENDICES ...................................................................................................................... 357

I. AUTHOR, REVIEWER AND STAFF INFORMATION ........................................................................ 357

II. UNIVERSAL DOCUMENTATION GUIDELINE .............................................................................. 363

III. MEDICATIONS ............................................................................................................... 377

IV. APPROVED ABBREVIATIONS .............................................................................................. 394

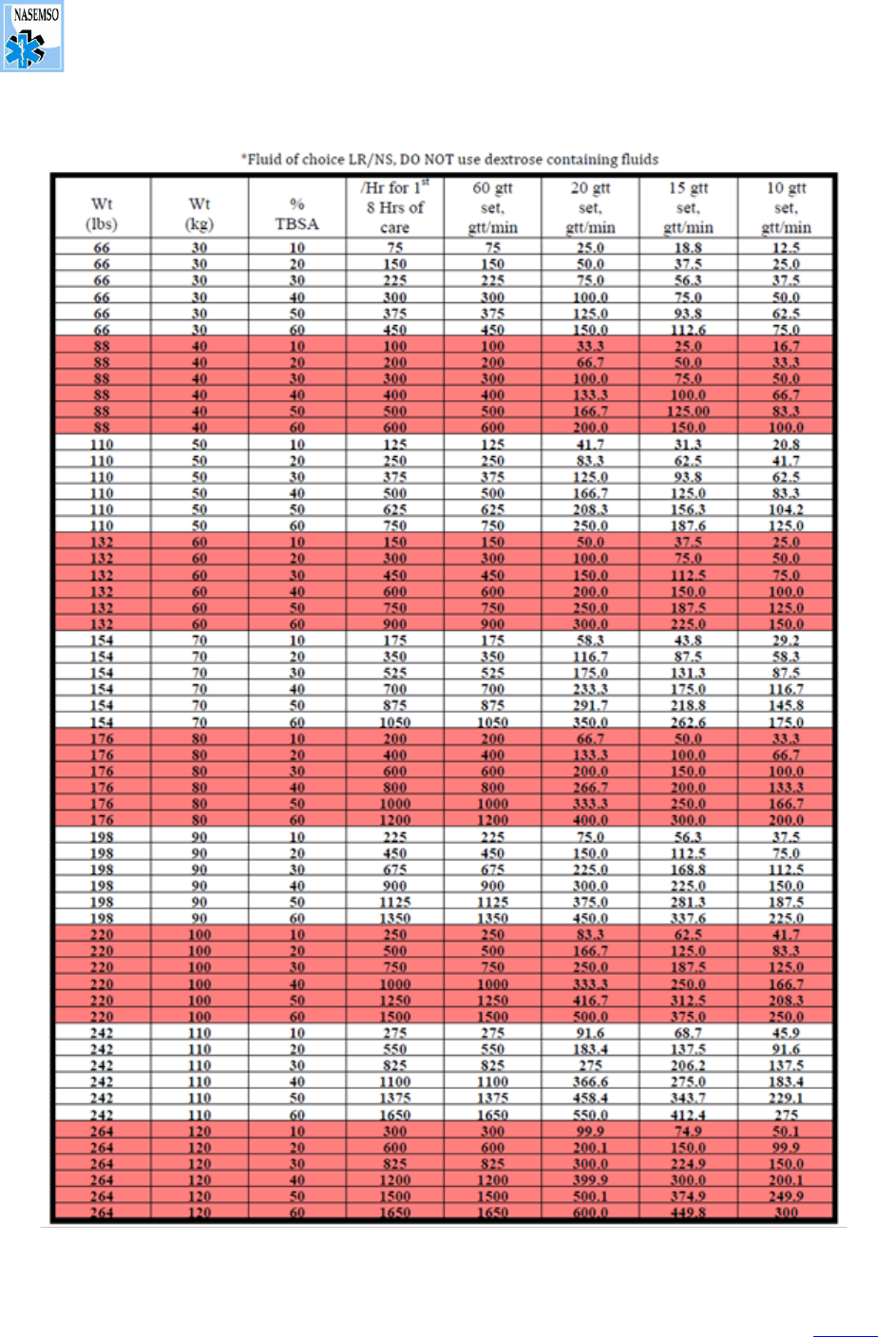

V. BURN AND BURN FLUID CHARTS ......................................................................................... 398

VI. NEUROLOGIC STATUS ASSESSMENT .................................................................................... 404

VII. ABNORMAL VITAL SIGNS ................................................................................................ 405

VIII. EVIDENCE-BASED GUIDELINES: GRADE METHODOLOGY ....................................................... 406

IX. 2022 NATIONAL GUIDELINE FOR THE FIELD TRIAGE OF INJURED PATIENTS .................................... 407

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

Rev. March 2022

5

Version 3.0

This publication was developed with funding from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration

(NHTSA), Office of Emergency Medical Services (Cooperative Agreement 693JJ92050001-0002) and the

Health Resources and Services Administration/Maternal and Child Health Bureau/EMS for Children

program. The opinions, findings, and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and

not necessarily those of the United States Government. The United States Government assumes no liability

for its content or use thereof. If trade or manufacturers’ names or products are mentioned, it is because

they are considered essential to the object of the publication and should not be construed as an

endorsement. The United States Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. For more

information, please visit EMS.gov and HRSA.gov.

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

Rev. March 2022

6

Version 3.0

Introduction

We are honored to present the third edition of the National Association of State EMS Officials (NASEMSO)

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines and want to thank the entire EMS community for contributing to its

evolution. The inaugural edition, released in September 2014, has been warmly welcomed by EMS

clinicians, agencies, medical directors, and healthcare organizations in our nation as well as abroad. The

creation of this document is a pinnacle event in the practice of EMS medicine as it fulfilled a

recommendation in The Future of Emergency Care: Emergency Medical Services at the Crossroads published

by the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academies of Sciences) in 2007. Specifically, this report

states “NHTSA, in partnership with professional organizations, should convene a panel of individuals with

multidisciplinary expertise to develop evidence-based model prehospital care protocols for the treatment,

triage, and transport of patients.”

The National Association of State EMS Officials (NASEMSO) recognizes the need for national EMS clinical

guidelines to help state EMS systems ensure a more standardized approach to the practice of patient care

now and, as experience dictates, the adoption of future practices. The value of EMS clinicians to the patient

has no boundaries as magnified by the historic 2019 novel coronavirus pandemic as well as other

interjurisdictional and global responses. Model EMS clinical guidelines promote uniformity in EMS medicine

which, in turn, fosters a more consistent skilled practice as EMS clinicians move across healthcare

systems. They also provide a standard to EMS medical directors upon which to base practice. Supported by

initial and subsequent grant funding from NHTSA’s Office of Emergency Medical Services (OEMS) and the

Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Maternal and Child Health Bureau’s EMS for Children

program, NASEMSO continues to authorize its Medical Directors Council to partner with national

stakeholder organizations with expertise in EMS medical direction and subject matter experts to create a

unified set of patient care guidelines. For those aspects of clinical care where evidence-based guidelines

derived in accordance with the national evidence-based guideline model process were not available,

consensus-based clinical guidelines are developed utilizing current available research.

The NASEMSO Model EMS Clinical Guidelines are not mandatory, are not meant to be all-inclusive, nor are

they meant to determine local scope of practice. The focus of these guidelines is solely patient-centric. As

such, they are designed to provide a resource for EMS clinical practice, appropriate patient care, safety of

patients and clinicians, and outcomes regardless of the existing resources and capabilities within an EMS

system. This document provides a clinical standard that can be used as is or adapted for use on a state,

regional, local, or organizational level to enhance patient care and to set benchmark performance of EMS

practice. The Guidelines should be adapted to align with federal, state, regional, and jurisdictional laws and

regulations. NASEMSO’s ongoing support of this project underlines the critical evolution of the model EMS

clinical guidelines as new EMS research and evidence-based patient care measures emerge.

We are most grateful to be able to partner with a group of talented, committed individuals in this

worthwhile endeavor.

Carol Cunningham, M.D. Richard Kamin, M.D.

Co-Principal Investigator Co-Principal Investigator

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

Rev. March 2022

7

Version 3.0

Purpose and Notes

These guidelines are intended to help state EMS systems ensure a more standardized approach to the

practice of patient care, and to encompass evidence-based guidelines (EBG) as they are developed.

The long-term goal is to develop a full range of evidence-based clinical guidelines for the practice of EMS

medicine. However, until there is a sufficient body of evidence to fully support this goal, there is a need for

this interim expert, consensus-based step.

The National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines can fill a significant gap in uniform clinical guidance for EMS

patient care, while also providing input to the evidence-based guideline (EBG) development process.

These guidelines will be maintained by the Medical Directors Council of the National Association of State

EMS Officials (NASEMSO) and will be reviewed and updated periodically. As EBG material is developed, it

will be substituted for the consensus-based guidelines now comprising the majority of the content of this

document. In the interim, additional consensus-based guidelines will also be added as the need is identified.

For guidelines to be considered for inclusion, they must be presented in the format followed by all

guidelines in the document.

Universal Care and Poisoning/Overdose Universal Care guidelines are included to reduce the need for

extensive reiteration of basic assessment and other considerations in every guideline.

The appendices contain material such as neurologic status assessment and burn assessment tools to which

many guidelines refer to increase consistency in internal standardization and to reduce duplication.

While some specific guidelines have been included for pediatric patients, considerations of patient age and

size (pediatric, geriatric, and bariatric) have been interwoven in the guidelines throughout the document.

Where IV access and drug routing are specified, it is intended to include IO access and drug routing when IV

access and drug routing is not possible.

Generic medication names are utilized throughout the guidelines. A complete list of these, along with

respective brand names, may be found in Appendix III. “Medications”.

Accurate and quality data collection is crucial to the advancement of EMS and a critical element of EMS

research. The National EMS Information System (NEMSIS) has the unique ability to unify EMS data on a

national scope to fulfill this need. Each guideline, therefore, is also listed by the closest NEMSIS Version 3

Label and Code corresponding to it, listed in parentheses below the guideline name.

Quality assurance (QA) and/or continued performance improvement (CPI) programs are an indispensable

element of medical direction as they facilitate the identification of gaps and potential avenues of their

resolution within an EMS system. The National EMS Quality Alliance (NEMSQA) Performance Measures is a

resource for these programs. This edition of the NASEMSO National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

incorporates many of the NEMSQA performance measures into the key performance measures associated

with each clinical guideline.

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

Rev. March 2022

8

Version 3.0

Target Audience

While this material is intended to be integrated into an EMS system’s operational guidance materials by its

medical director and other leaders, it is written with the intention that it will be consumed by field EMS

clinicians.

To the degree possible, it has been assembled in a format useful for guidance and quick reference so that

leaders may adopt it in whole or in part, harvesting and integrating as they deem appropriate to the format

of their guideline, protocol, or procedure materials.

Any set of guidelines must determine a balance between education and patient care. This document

purposefully focuses on the patient care aspect of EMS response. This does not preclude the individual

medical director from using these guidelines and including additional education as well as incorporation of

state, local, or jurisdictional operational procedures.

What is New in the 2022 Edition

All of the 2017 guidelines have been reviewed and updated, and additional guidelines and new evidence-

based guidelines have been added to this edition. While some of the new material has been added as

guidelines in the appropriate chapter, other topics have been incorporated into a previously existing

guideline. New guidelines have been added to the 2022 edition for the following clinical conditions or

scenarios:

•

Brief Resolved Unexplained Event (BRUE) & Acute Events in Infants

•

Resuscitation in Traumatic Cardiac Arrest

•

Tracheostomy Management

•

Trauma Mass Casualty Incident

In addition, with the permission and assistance of the American College of Surgeons – Committee on

Trauma, we have included the 2022 National Guideline for the Field Triage of Injured Patients as Appendix

IX.

Acknowledgements

The authors of this document are NASEMSO Medical Director Council members partnered with

representatives of seven EMS medical director stakeholder organizations. The stakeholder organizations are

the American Academy of Emergency Medicine (AAEM), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the

American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP), the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma

(ACS-COT), the Air Medical Physician Association (AMPA), and the National Association of EMS Physicians

(NAEMSP).

In honor and gratitude, the authors of the inaugural NASEMSO National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines are

also included. Their invaluable contributions and expertise to build the foundation of this evolutionary

document will always be deeply respected and appreciated.

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

________________________ Go To TOC

Universal Care Rev. March 2022

Universal Care Guideline 9

Version 3.0

Universal Care

Universal Care Guideline

Aliases

Patient assessment Patient history Physical assessment

Primary survey Secondary survey

Patient Care Goals

Facilitate appropriate initial assessment and management of any EMS patient and link to appropriate

specific guidelines as dictated by the findings within the Universal Care guideline

Patient Presentation

Inclusion Criteria

All patient encounters with and care delivery by EMS personnel

Exclusion Criteria

None

Patient Management

Assessment

1. Assess scene safety

a. Evaluate for hazards to EMS personnel, patient, bystanders

b. Safely remove patient from hazards prior to beginning medical care

c. Determine number of patients

d. Determine mechanism of injury or potential source of illness

e. Request additional resources if needed and weigh the benefits of waiting for additional

resources against rapid transport to definitive care

f. Consider declaration of mass casualty incident if needed

2. Use appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE)

a. Consider suspected or confirmed hazards on scene

b. Consider suspected or confirmed highly contagious infectious disease (e.g., contact [bodily

fluids], droplet, airborne)

3. Wear high-visibility, retro-reflective apparel when deemed appropriate (e.g., operations at night

or in darkness, on or near roadways)

4. Consider cervical spine stabilization and/or spinal care if traumatic injury suspected. [See Spine

Care Guideline]

5. Primary survey

(Airway, Breathing, Circulation (ABC) is cited below; although there are specific circumstances

where Circulation, Airway, Breathing (CAB) may be indicated, such as for cardiac arrest, or

Massive hemorrhage, Airway, Respirations, Circulation, Hypothermia and head injury (MARCH)

may be indicated for trauma or major arterial bleeding)

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

________________________ Go To TOC

Universal Care Rev. March 2022

Universal Care Guideline 10

Version 3.0

a. Airway (assess for patency and open the airway as indicated) – go to Airway Management

Guideline

i. Patient is unable to maintain airway patency—open airway

1. Head tilt/chin lift

2. Jaw thrust

3. Suction

4. Consider use of the appropriate airway management adjuncts and devices: oral

airway, nasal airway, supraglottic airway device or endotracheal tube

5. For patients with laryngectomies or tracheostomies, remove all objects or clothing

that may obstruct the opening of these devices, maintain the flow of prescribed

oxygen, and reposition the head and/or neck

b. Breathing

i. Evaluate rate, breath sounds, accessory muscle use, retractions, patient positioning,

oxygen saturation

ii. Provide supplemental oxygen as appropriate to achieve the target of 94–98% oxygen

saturation (SPO

2

) based upon clinical presentation and assessment of ventilation (e.g.,

EtCO

2

)

iii. Apnea (not breathing) – go to Airway Management Guideline

c. Circulation

i. Control any major external bleeding [See General Trauma Management Guideline

and/or Extremity Trauma/External Hemorrhage Management Guideline]

ii. Assess pulse

1. If none – go to Resuscitation Section

2. Assess rate and quality of carotid and radial pulses

iii. Evaluate perfusion by assessing skin color and temperature

1. Evaluate capillary refill

d. Disability

i. Evaluate patient responsiveness: AVPU (Alert, Verbal, Painful, Unresponsive)

ii. Evaluate gross motor and sensory function in all extremities

iii. Check blood glucose in patients with altered mental status (AMS) or suspected stroke. If

blood glucose is less than 60 mg/dL – go to Hypoglycemia Guideline

iv. If acute stroke suspected – go to Suspected Stroke/Transient Ischemic Attack Guideline

e. Expose patient for exam as appropriate to complaint

i. Be considerate of patient modesty

ii. Keep patient warm

6. Assess for urgency of transport

7. Secondary survey

The performance of the secondary survey should not delay transport in critical patients. See

also secondary survey specific to individual complaints in other protocols. Secondary surveys

should be tailored to patient presentation and chief complaint. The following are suggested

considerations for secondary survey assessment:

a. Head

i. Pupils

ii. Ears

iii. Naso-oropharynx

iv. Skull and scalp

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

________________________ Go To TOC

Universal Care Rev. March 2022

Universal Care Guideline 11

Version 3.0

b. Neck

i. Jugular venous distension

ii. Tracheal position

iii. Spinal tenderness

c. Chest

i. Retractions

ii. Breath sounds

iii. Chest wall tenderness, deformity, crepitus, and excursion

iv. Respiratory pattern, symmetry of chest movement with respiration

d. Abdomen/Back

i. Tenderness or bruising

ii. Abdominal distension, rebound, or guarding

iii. Spinal tenderness, crepitus, or step-offs

iv. Pelvic stability or tenderness

e. Extremities

i. Pulses

ii. Edema

iii. Deformity/crepitus

f. Neurologic

i. Mental status/orientation

ii. Motor/sensory

g. Evaluate for medical equipment (e.g., pacemaker/defibrillator, left ventricular assist device

(LVAD), insulin pump, dialysis fistula)

8. Obtain baseline vital signs (an initial full set of vital signs is required: pulse, blood pressure,

respiratory rate, neurologic status assessment and obtain pulse oximetry if indicated)

a. Neurologic status assessment [See Appendix VII. Neurologic Status Assessment] involves

establishing a baseline and then trending any change in patient neurologic status

i. Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) is frequently used, but there are often errors in applying and

calculating this score. With this in consideration, a more simple field approach may be

as valid as GCS. Either AVPU or only the motor component of the GCS may more

effectively serve in this capacity

ii. Sternal rub as a stimulus is discouraged

b. Patients with cardiac or respiratory complaints

i. Pulse oximetry

ii. 12-lead electrocardiogram (EKG) should be obtained promptly in patients with cardiac

or suspected cardiac complaints

iii. Continuous cardiac monitoring, if available

iv. Consider waveform capnography for patients with respiratory complaints (essential for

critical patients and those patients who require invasive airway management)

c. Patient with altered mental status

i. Check blood glucose. If low, go to Hypoglycemia Guideline

ii. Consider waveform capnography (essential for critical patients and those patients who

require invasive airway management) or digital capnometry

d. Stable patients should have at least two sets of pertinent vital signs. Ideally, one set should

be taken shortly before arrival at receiving facility

e. Critical patients should have pertinent vital signs frequently monitored

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

________________________ Go To TOC

Universal Care Rev. March 2022

Universal Care Guideline 12

Version 3.0

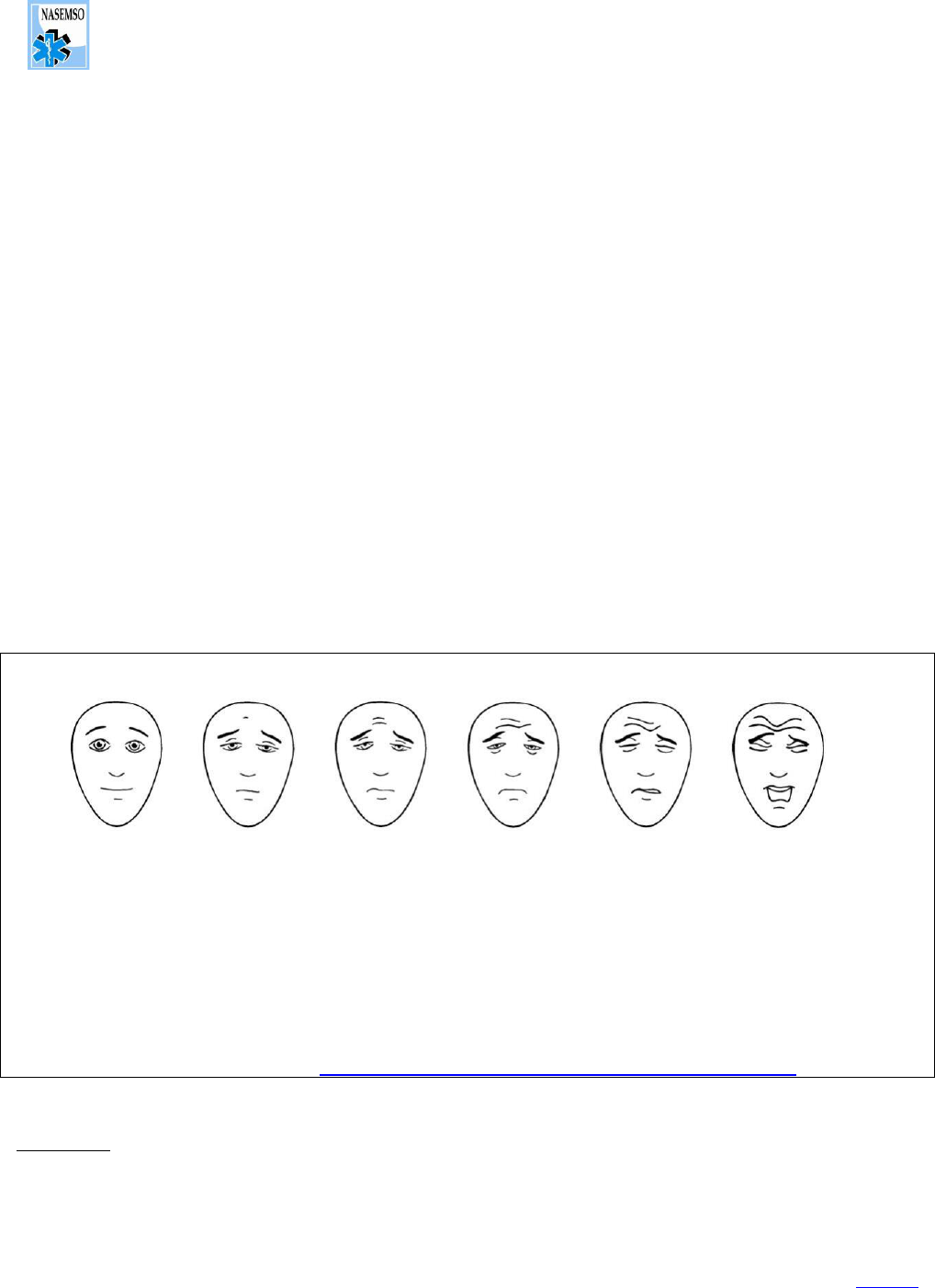

9. Obtain OPQRST history:

a. Onset of symptoms

b. Provocation: location; any exacerbating or alleviating factors

c. Quality of pain

d. Radiation of pain

e. Severity of symptoms: pain scale

f. Time of onset and circumstances around onset

10. Obtain SAMPLE history:

a. Symptoms

b. Allergies: medication, environmental, and foods

c. Medications: prescription and over the counter; bring containers to ED if possible

d. Past medical history

i. Look for medical alert tags, portable medical records, advance directives

ii. Look for medical devices/implants (some common ones may be dialysis shunt, insulin

pump, pacemaker, central venous access port, gastric tubes, urinary catheter)

iii. For females of childbearing age, inquire of potential or recent pregnancy.

e. Last oral intake

f. Events leading up to the 911 call

In patients with syncope, seizure, altered mental status, or acute stroke, consider bringing

the witness to the hospital or obtain their contact phone number to provide to ED care

team

Treatment and Interventions

1. Administer oxygen as appropriate with a target of achieving 94–98% saturation and select the

appropriate method of oxygen delivery to mitigate or treat hypercarbia associated with

hypoventilation

2. Place appropriate monitoring equipment as dictated by assessment; these may include:

a. Continuous pulse oximetry

b. Cardiac rhythm monitoring

c. Waveform capnography or digital capnometry

d. Carbon monoxide assessment

3. Establish vascular access if indicated or in patients who are at risk for clinical deterioration.

a. If IO is to be used for a conscious patient, consider the use of 0.5 mg/kg of lidocaine 0.1

mg/mL with slow push through IO needle to a maximum of 40 mg to mitigate pain from IO

medication administration

4. Monitor pain scale if appropriate

5. Monitor agitation-sedation scale if appropriate

6. Reassess patient

Transfer of Care

1. The content and quality of information provided during the transfer of patient care to

another party is critical for seamless patient care and maintenance of patient safety

2. Ideally, a completed electronic or written medical record should be provided to the next

caregiver at the time of transfer of care

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

________________________ Go To TOC

Universal Care Rev. March 2022

Universal Care Guideline 13

Version 3.0

3. If provision of the completed medical record is not possible at the time of transfer of care, a

verbal report and an abbreviated written run report should be provided to the next caregiver

4. The information provided during the transfer of care should include, but is not limited to,

a. Patient’s full name

b. Age

c. Chief complaint

d. History of present illness/Mechanism of injury

e. Past medical history

f. Medications

g. Allergies

h. Vital signs with documented times

i. Patient assessment and interventions along with the timing of any medication or

intervention and the patient’s response to such interventions

5. The verbal or abbreviated written run report provided at the time of transfer of care does not

take the place of or negate the requirement for the provision of a complete electronic or

written medical record of the care provided by EMS personnel

Patient Safety Considerations

1. Routine use of lights and sirens is not warranted

2. Even when lights and sirens are in use, always limit speeds to level that is safe for the

emergency vehicle being driven and road conditions on which it is being operated

3. Be aware of legal issues and patient rights as they pertain to and impact patient care (e.g.,

patients with functional needs or children with special healthcare needs)

4. Be aware of potential need to adjust management based on patient age and comorbidities,

including medication dosages

5. The maximum weight-based dose of medication administered to a pediatric patient should not

exceed the maximum adult dose except where specifically stated in a patient care guideline

6. Medical direction should be contacted when mandated or as needed

7. Consider air medical transport, if available, for patients with time-critical conditions where

ground transport time exceeds 30 minutes

Notes/Educational Pearls

Key Considerations

1. Pediatrics: use a weight-based assessment tool (length-based tape or other system) to estimate

patient weight and guide medication therapy and adjunct choice

a. Although the defined age varies by state, the pediatric population is generally defined by

those patients who weigh up to 40 kg or up to 14 years of age, whichever comes first

b. Consider using the pediatric assessment triangle (appearance, work of breathing,

circulation) when first approaching a child to help with assessment

2. Geriatrics: although the defined age varies by state, the geriatric population is generally defined

as those patients who are 65 years old or more

a. In these patients, as well as all adult patients, reduced medication dosages may apply to

patients with renal disease (i.e., on dialysis or a diagnosis of chronic renal insufficiency) or

hepatic disease (i.e., severe cirrhosis or end-stage liver disease)

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

________________________ Go To TOC

Universal Care Rev. March 2022

Universal Care Guideline 14

Version 3.0

3. Co-morbidities: reduced medication dosages may apply to patients with renal disease (i.e., on

dialysis or a diagnosis of chronic renal insufficiency) or hepatic disease (i.e., severe cirrhosis or

end-stage liver disease)

4. Vital Signs:

a. Oxygen

i. Administer oxygen as appropriate with a target of achieving 94–98% saturation

ii. Supplemental oxygen administration is warranted to patients with oxygen saturations

below this level and titrated based upon clinical condition, clinical response, and

geographic location and altitude

iii. The method of oxygen delivery should minimize or treat hypercarbia associated with

hypoventilation (e.g., non-invasive positive airway pressure devices)

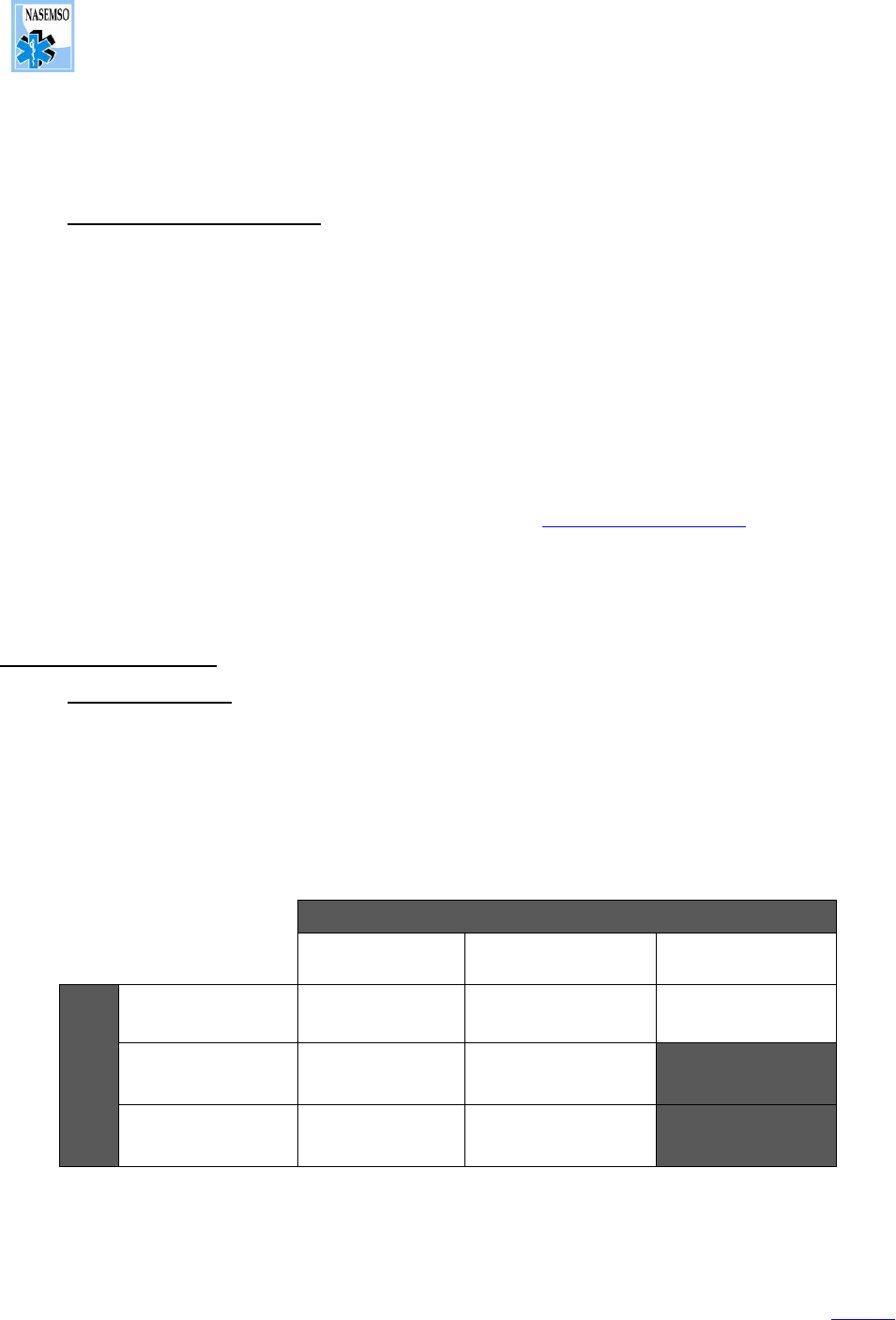

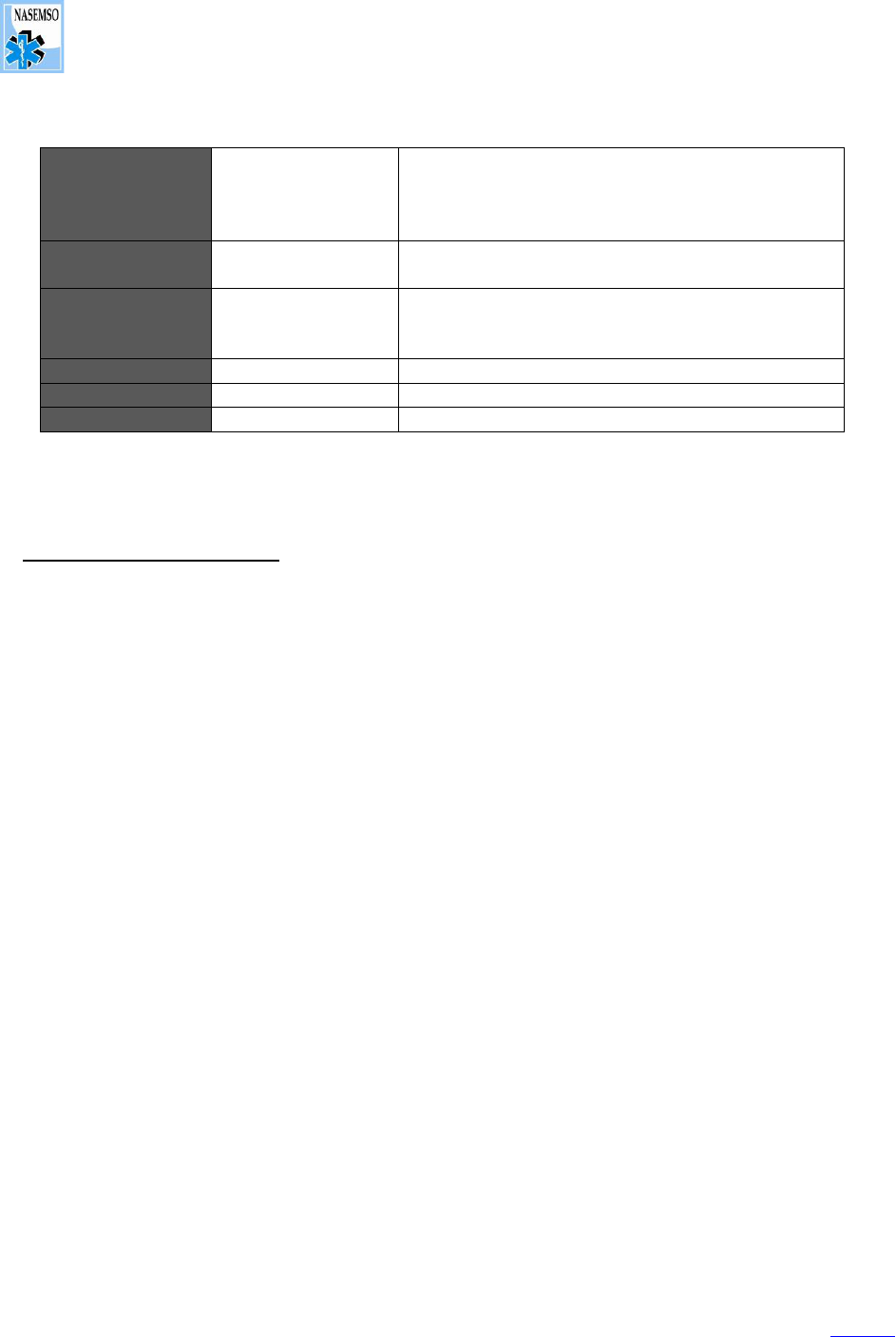

b. Normal vital signs (See Table 1. Normal Vital Signs)

i. Hypotension is considered a systolic blood pressure less than the lower limit on the

chart

ii. Tachycardia is considered a pulse above the upper limit on the chart

iii. Bradycardia is considered a pulse below the lower limit on the chart

iv. Tachypnea is considered a respiratory rate above the upper limit on the chart

v. Bradypnea is considered a respiratory rate below the lower limit on the chart

c. Hypertension. Although abnormal, may be an expected finding in many patients

i. Unless an intervention is specifically suggested based on the patient’s complaint or

presentation, the hypertension should be documented, but otherwise, no intervention

should be taken acutely to normalize the blood pressure

ii. The occurrence of symptoms (e.g., chest pain, dyspnea, vision change, headache, focal

weakness or change in sensation, altered mental status) in patients with hypertension

should be considered concerning, and care should be provided appropriate with the

patient’s complaint or presentation

5. Secondary Survey: if patient has critical primary survey problems, it may not be possible to

complete

6. Critical Patients: proactive patient management should occur simultaneously with assessment

a. Ideally, one clinician should be assigned to exclusively monitor and facilitate patient-

focused care

b. Other than lifesaving interventions that prevent deterioration en route, treatment and

Interventions should be initiated as soon as practical, but should not impede extrication or

delay transport to definitive care

7. Air Medical Transport: air transport of trauma patients should generally be reserved for higher

acuity trauma patients where there is a significant time saved over ground transport, where the

appropriate destination is not accessible by ground due to systemic or logistical issues, and for

patients who meet the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma (ACS-COT) 2022

National Guideline for the Field Triage of Injured Patients anatomic, physiologic, and situational

high-acuity triage criteria. In selected circumstances, air medical resources may be helpful for

non-trauma care (e.g., stroke, STEMI when geographically constrained)

8. Additional Protective Measures for the EMS Clinician: Due to suspected or confirmed hazards

and/or highly infectious contagious diseases, traditional patient treatment and care delivery

may be altered due to recommendations by federal, state, local or jurisdictional officials

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

________________________ Go To TOC

Universal Care Rev. March 2022

Universal Care Guideline 15

Version 3.0

Pertinent Assessment Findings

Refer to individual guidelines

Quality Improvement

Associated NEMSIS Protocol(s) (eProtocol.01) (for additional information, go to www.nemsis.org)

•

9914075 – General - Universal Patient Care/Initial Patient Contact

Key Documentation Elements

• At least two sets of vital signs should be documented for every patient

• All patient interventions and response to care should be documented

• All major changes in clinical status including, but not limited to, vital signs and data from

monitoring equipment, should be documented

Performance Measures

• Abnormal vital signs should be addressed and reassessed

• Response to therapy provided should be documented including pain scale or agitation-sedation

scale (e.g., Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS)) reassessment if appropriate

• Limit scene time for patients with time-critical illness or injury unless clinically indicated

• Appropriate utilization of air medical services

• Blood glucose level obtained when indicated

• Compliance with provision of critical information during patient transfer of care

• National EMS Quality Alliance (NEMSQA) Performance Measures (for additional information,

see www.nemsqa.org )

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

________________________ Go To TOC

Universal Care Rev. March 2022

Universal Care Guideline 16

Version 3.0

Table 1. Normal Vital Signs

Age

Pulse-Awake

(beats/

minute)

Pulse-Sleeping

(beats/

minute)

Respiratory

Rate

(breaths/

minute)

Systolic

BP

(mmHg)

Preterm less than 1 kg

120–160

30–60

39–59

Preterm 1–3 kg

120–160

30–60

60–76

Newborn

100–205

85–160

30–60

67–84

Up to 1 year

100–190

90–160

30–60

72–104

1–2 years

100–190

90–160

24–40

86–106

2–3 years

98–140

60–120

24–40

86–106

3–4 years

80–140

60–100

24–40

89–112

4–5 years

80–140

60–100

22–34

89–112

5–6 years

75–140

58–90

22–34

89–112

6–10 years

75–140

58–90

18–30

97–115

10–12 years

75–118

58–90

18–30

102–120

12–13 years

60–100

58–90

15–20

110–131

13–15 years

60–100

50–90

15–20

110–131

15 years or older

60–100

50–90

15–20

110–131

Source: Extrapolated from the 2020 American Heart Association Pediatric Advanced Life Support’s

tables from the Nursing Care of the Critically Ill Child, and from Web Box 1: Existing reference ranges

for respiratory rate and heart rate in the appendix of the article by Fleming, et al, published in Lancet

Note: While many factors affect blood pressure (e.g., pain, activity, hydration), it is imperative to

rapidly recognize hypotension, especially in children. For children of the ages 1–10, hypotension is

present if the systolic blood pressure is less than 70 mmHg + (child’s age in years x 2) mmHg.

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

________________________ Go To TOC

Universal Care Rev. March 2022

Universal Care Guideline 17

Version 3.0

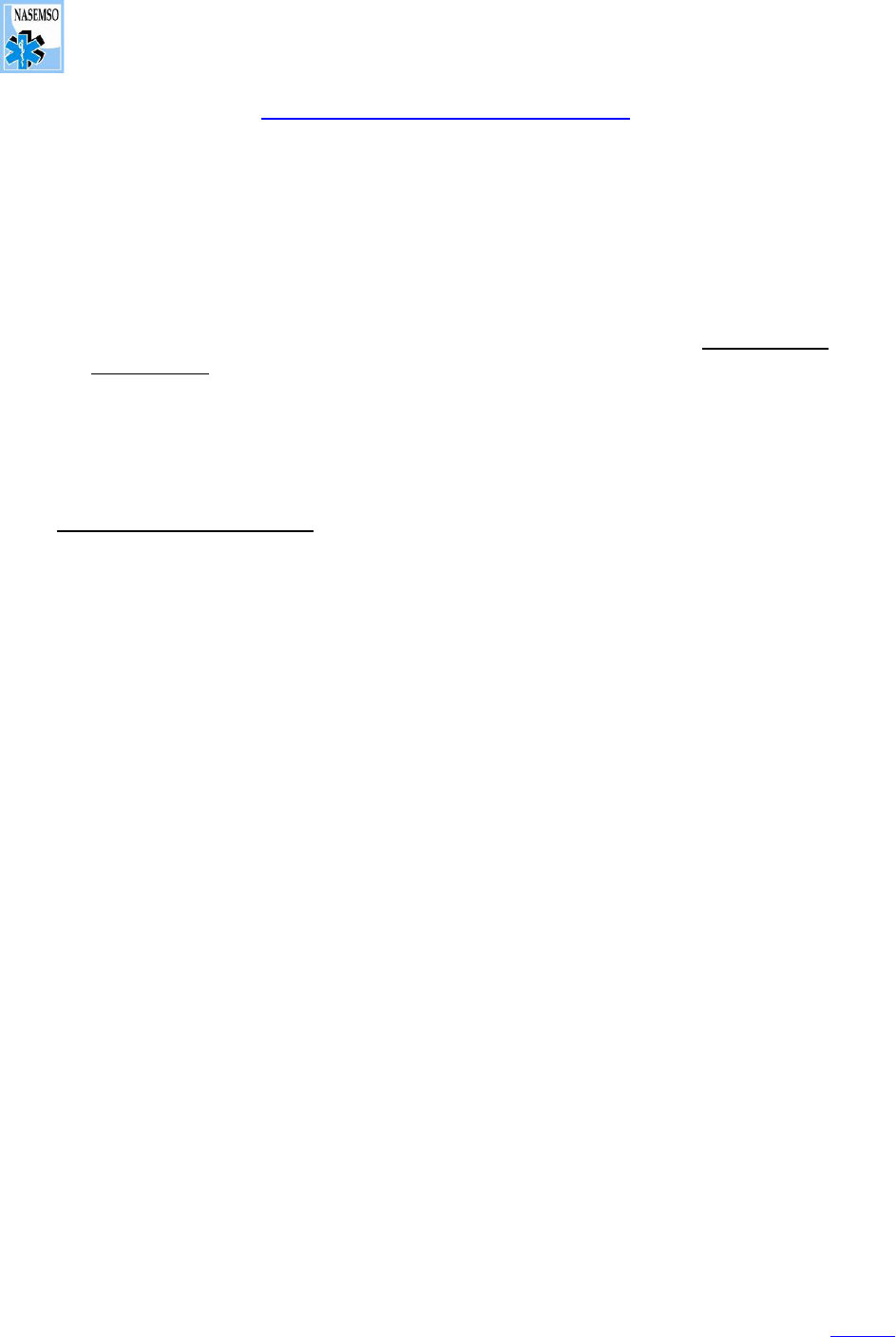

Table 2. Glasgow Coma Scale

ADULT GLASGOW COMA SCALE

PEDIATRIC GLASGOW COMA SCALE

Eye Opening (4)

Eye Opening (4)

Spontaneous

4

Spontaneous

4

To Speech

3

To Speech

3

To Pain

2

To Pain

2

None

1

None

1

Best Motor Response (6)

Best Motor Response (6)

Obeys Commands

6

Spontaneous Movement

6

Localizes Pain

5

Withdraws to Touch

5

Withdraws from Pain

4

Withdraws from Pain

4

Abnormal Flexion

3

Abnormal Flexion

3

Abnormal Extension

2

Abnormal Extension

2

None

1

None

1

Verbal Response (5)

Verbal Response (5)

Oriented

5

Coos, Babbles

5

Confused

4

Irritable Cry

4

Inappropriate

3

Cries to Pain

3

Incomprehensible

2

Moans to Pain

2

None

1

None

1

Total

Total

Source: https://www.cdc.gov/masstrauma/resources/gcs.pdf

References

1. 2020 Pediatric Advanced Life Support Provider Manual, American Heart Association, 2020

2. Bass, R. R., Lawner, B., Lee, D. and Nable, J. V. 2015 Medical oversight of EMS systems, in

Emergency Medical Services: Clinical Practice and Systems Oversight, Second Edition (eds D. C.

Cone, J. H. Brice, T. R. Delbridge and J. B. Myers), John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Chichester, UK

3. Bledsoe BE, Porter RS, Cherry RA. Paramedic Care: Principles & Practice, Volume 3, 4

th

Ed. Brady,

2012

4. Duckworth, Rom, EMS Trauma Care: ABCs vs. MARCH, Rescue Digest, September 1, 2017

5. Emergency Cardiovascular Care: For Healthcare Providers. American Heart Association, 2020.

6. Fleming, S, et al, Normal ranges of heart rate and respiratory rate in children from birth to 18

years: a systematic review of observational studies, Lancet, March 19, 2011,377(9770),1011–

1018

7. Gerecht, Ryan, et al, “Understanding when to Request a Helicopter for Your Patient”, Journal of

EMS, October 3, 2014. https://www.jems.com/operations/ambulances-vehicle-

ops/understanding-when-request-helicopter-yo/. Accessed March 11, 2022

8. Gill M, Steele R, Windemuth R, Green SM. A comparison of five simplified scales to the out-of-

hospital Glasgow Coma Scale for the prediction of traumatic brain injury outcomes. Acad Emerg

Med. 2006;13(9):968–73

9. Haziinski, MF, Children are Different, Nursing Care of the Critically Ill Child, 3rd ed, Mosby,

2013,1–18

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

________________________ Go To TOC

Universal Care Rev. March 2022

Universal Care Guideline 18

Version 3.0

10. Kupas, D. Lights and Siren Use by Emergency Medical Services (EMS): Above All Do No Harm.

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Contract DTNH22-14-F-00579. Published May

2017

11. National Association of State Emergency Medical Services Officials. State model rules for the

regulation of air medical services. September 2016

12. O’Driscoll BR, Howard LS, Davison AG. BTS guideline for emergency oxygen use in adult patients.

Thorax 2008;63:vi1-vi68

13. Thomas SH, Brown KM, Oliver ZJ, Spaite DW, Sahni R, Weik TS, et al. An evidence-based

guideline for the air medical transportation of trauma patients. Prehosp Emerg Care 2014;18

Suppl 1:35–44

14. U.S. Fire Administration. Traffic incident management systems, FA-330. March 2012.

https://www.usfa.fema.gov/downloads/pdf/publications/fa_330.pdf. Accessed March 11, 2022

Revision Date

March 24, 2022

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

________________________ Go To TOC

Universal Care Rev. March 2022

Functional Needs 19

Version 3.0

Functional Needs

Aliases

Developmental delay Disabled Handicapped

Impaired Mental Illness Intellectual Disability

Special needs

Patient Care Goals

To meet and maintain the additional support required for patients with functional needs during the delivery

of prehospital care

Patient Presentation

Inclusion Criteria

Patients who are identified by the World Health Organization’s International Classification of

Functioning, Disability, and Health that have experienced a decrement in health resulting in some

degree of disability. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, this includes,

but is not limited to, individuals with physical, sensory, mental health, and cognitive and/or

intellectual disabilities affecting their ability to function independently without assistance

Exclusion Criteria

None noted

Patient Management

Assessment

1. Identify the functional need by means of information from the patient, the patient’s family,

bystanders, medic alert bracelets or documents, or the patient’s adjunct assistance devices

2. The physical examination should not be intentionally abbreviated, although the way the exam is

performed may need to be modified to accommodate the specific needs of the patient

Treatment and Interventions

Medical care should not intentionally be reduced or abbreviated during the triage, treatment, and

transport of patients with functional needs, although the way the care is provided may need to be

modified to accommodate the specific needs of the patient

Patient Safety Considerations

For patients with communication barriers (language or sensory), it may be desirable to obtain

secondary confirmation of pertinent data (e.g., allergies) from the patient’s family, interpreters, or

written or electronic medical records. The family members can be an excellent source of

information and the presence of a family member can have a calming influence on some of these

patients

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

________________________ Go To TOC

Universal Care Rev. March 2022

Functional Needs 20

Version 3.0

Notes/Educational Pearls

Key Considerations

1. Communication Barriers

a. Language Barriers:

i. Expressive and/or receptive aphasia

ii. Nonverbal

iii. Fluency in a different language than that of the EMS professional

iv. Examples of tools to overcome language barriers include:

1. Transport of an individual who is fluent in the patient’s language along with the

patient to the hospital

2. Medical translation cards

3. Telephone-accessible services with live language interpreters

4. Methods through which the patient augments his/her communication skills (e.g.,

eye blinking, nodding) should be noted, utilized as able, and communicated to the

receiving facility

5. Electronic applications for translation

b. Sensory Barriers:

i. Visual impairment

ii. Auditory impairment

iii. Examples of tools to overcome sensory barriers include:

1. Braille communication card

2. Sign language

3. Lip reading

4. Hearing aids

5. Written communication

2. Physical Barriers:

a. Ambulatory impairment (e.g., limb amputation, bariatric)

b. Neuromuscular impairment

3. Cognitive Barriers:

a. Mental illness

b. Developmental challenge or delay

Pertinent Assessment Findings

1. Assistance Adjuncts. Examples of devices that facilitate the activities of daily living for the

patient with functional needs include, but are not limited to:

a. Extremity prostheses

b. Hearing aids

c. Magnifiers

d. Tracheostomy speaking valves

e. White or sensory canes

f. Wheelchairs or motorized scooters

2. Service Animals

As defined by the American Disabilities Act, “any guide dog, signal dog, or other animal

individually trained to do work or perform tasks for the benefit of an individual with a disability,

including, but not limited to guiding individuals with impaired vision, alerting individuals with

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

________________________ Go To TOC

Universal Care Rev. March 2022

Functional Needs 21

Version 3.0

impaired hearing to intruders or sounds, providing minimal protection or rescue work, pulling a

wheelchair, or fetching dropped items”

a. Services animals are not classified as a pet and should, by law, always be permitted to

accompany the patient with the following exceptions:

i. A public entity may ask an individual with a disability to remove a service animal from

the premises if:

1. The animal is out of control and the animal's handler does not take effective action

to control it; or

2. The animal is not housebroken

b. Service animals are not required to wear a vest or a leash. It is illegal to make a request for

special identification or documentation from the service animal’s partner. EMS clinicians

may only ask the patient if the service animal is required because of a disability and the

form of assistance the animal has been trained to perform.

c. EMS clinicians are not responsible for the care of the service animal. If the patient is

incapacitated and cannot personally care for the service animal, a decision can be made

whether to transport the animal in this situation.

d. Animals that solely provide emotional support, comfort, or companionship do not qualify as

service animals

Quality Improvement

Associated NEMSIS Protocol(s) (eProtocol.01) (for additional information, go to www.nemsis.org)

•

9914063 – General - Individualized Patient Protocol

•

9914165 – Other

Key Documentation Elements

• Document all barriers in the NEMSIS element “eHistory.01 – Barriers to Patient Care” (NEMSIS

Required National Element)

• Document specific physical barriers in the appropriate exam elements (e.g., “blind” under Eye

Assessment; or paralysis, weakness, or speech problems under Neurological Assessment)

• Document any of the following, as appropriate in the narrative:

o Language barriers:

▪ The patient’s primary language of fluency

▪ The identification of the person assisting with the communication

▪ The methods through which the patient augments his/her communication skills

o Sensory barriers:

▪ The methods through which the patient augments his/her communication skills

▪ Written communication between the patient and the EMS professional is part of the

medical record, even if it is on a scrap sheet of paper, and it should be retained with the

same collation, storage, and confidentiality policies and procedures that are applicable

to the written or electronic patient care report

o Assistance adjuncts (devices that facilitate the activities of life for the patient)

Performance Measure

• Accuracy of key data elements (chief complaint, past medical history, medication, allergies)

• Utilization of the appropriate adjuncts to overcome communication barriers

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

________________________ Go To TOC

Universal Care Rev. March 2022

Functional Needs 22

Version 3.0

• Documentation of the patient’s functional need and avenue exercised to support the patient

• Documentation of complete and accurate transfer of information regarding the functional need

to the receiving facility

• Barriers documented under “eHistory.01—Barriers to Patient Care”

References

1.

International classification of functioning, disability, and health. Presented at: 54

th

World Health

Assembly, WHA 54.21, Agenda Item 13.9; May 21, 2001

2.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Assistant Secretary of

Preparedness and Response. FEMA’s Functional Needs Support Services Guidance. 2012.

http://www.phe.gov/Preparedness/planning/abc/Documents/fema-fnss.pdf. Accessed August

18, 2017

3.

US Department of Labor. Americans with Disabilities Act; 28 Code of Federal Regulations Part

35. July 23, 2010

4.

US Department of Labor. Americans with Disabilities Act; 42 U.S. Code, Chapter 126. 1990

5.

US Department of Labor. Americans with Disabilities Act; Amendments Act; 42 U.S. Code. 2008

Revision Date

March 11, 2022

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

________________________ Go To TOC

Universal Care Rev. March 2022

Patient Refusals 23

Version 3.0

Patient Refusals

Aliases

Against medical advice Refusal of treatment Refusal of transport

Patient Care Goals/Patient Presentation (Overview)

If an individual (or the parent or legal guardian of the individual) refuses secondary care and/or ambulance

transport to a hospital after prehospital clinicians have been called to the scene, clinicians should determine

the patient’s capacity to make decisions. Competency is generally a legal status of a person’s ability to make

decisions. However, state laws vary in the definition of competency and its impact upon authority.

Therefore, one should consult with the respective state EMS office for clarification on legal definitions and

patient rights.

Patient Management

Assessment

1. Decision-Making Capacity

a. An individual who is alert, oriented, and can understand the circumstances surrounding

his/her illness or impairment, as well as the possible risks associated with refusing

treatment and/or transport, typically is considered to have decision-making capacity

b. The individual’s judgment must also not be significantly impaired by illness, injury, or

drugs/alcohol intoxication. Individuals who have attempted suicide, verbalized suicidal

intent, or had other factors that lead EMS clinicians to suspect suicidal intent, should not be

regarded as having decision-making capacity and may not decline transport to a medical

facility

Treatment and Interventions

1. Obtain a complete set of vital signs and complete an initial assessment, paying particular

attention to the individual’s neurologic and mental status

2. Determine the individual’s capacity to make a valid judgment concerning the extent of his/her

illness or injury; if the EMS clinician has doubts about whether the individual has the mental

capacity to refuse or if the patient lacks capacity, the EMS clinician should contact medical

direction

3. If patient has capacity, clearly explain to the individual and all responsible parties the possible

risks and overall concerns with regards to refusing care and that they may reengage the EMS

system if needed

4. Perform appropriate medical care with the consent of the individual

5. Complete the patient care report clearly documenting the initial assessment findings and the

discussions with all involved individuals regarding the possible consequences of refusing

additional prehospital care and/or transportation

Notes/Educational Pearls

Key Considerations

1. An adult or emancipated minor who has demonstrated possessing sufficient mental capacity for

making decisions has the right to determine the course of his/her medical care, including the

refusal of care

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

________________________ Go To TOC

Universal Care Rev. March 2022

Patient Refusals 24

Version 3.0

2. Individuals must be advised of the risks and consequences resulting from refusal of medical care

to enable an informed decision regarding consent or refusal of treatment

3. An individual determined to lack decision-making capacity by EMS clinicians should not be

allowed to refuse care against medical advice or to be released at the scene. Mental illness,

drugs, alcohol intoxication, or physical/mental impairment may significantly impair an

individual’s decision-making capacity. Individuals who have attempted suicide, verbalized

suicidal intent, or had other factors that lead EMS clinicians to suspect suicidal intent, should

not be regarded as having demonstrated sufficient decision-making capacity

4. The determination of decision-making capacity may be challenged by communication barriers

or cultural differences

5. EMS clinicians should not put themselves in danger by attempting to treat and/or transport an

individual who refuses care. Law enforcement personnel should be requested if needed

6. Always act in the best interest of the patient. EMS clinicians, with the support of direct medical

oversight, must strike a balance between abandoning the patient and forcing care

7. Special Considerations – Minors

It is preferable for minors to have a parent or legal guardian who can provide consent for

treatment on behalf of the child

a. All states allow healthcare clinicians to provide emergency treatment when a parent is not

available to provide consent. This is known as the emergency exception rule or the doctrine

of implied consent. For minors, this doctrine means that the EMS clinician can presume

consent and proceed with appropriate treatment and transport if the following six

conditions are met:

i. The child is suffering from an emergent condition that places their life or health in

danger

ii. The child’s legal guardian is unavailable or unable to provide consent for treatment or

transport

iii. Treatment or transport cannot be safely delayed until consent can be obtained

iv. The EMS clinician administers only treatment for emergency conditions that pose an

immediate threat to the child

v. As a rule, when the EMS clinician’s authority to act is in doubt, EMS clinicians should

always do what they believe to be in the best interest of the minor

vi. If a minor is injured or ill and no parent contact is possible, the EMS clinician may

contact medical direction for additional instructions

Quality Improvement

Associated NEMSIS Protocol(s) (eProtocol.01) (for additional information, go to www.nemsis.org)

•

9914189 – General - Refusal of Care

Key Documentation Elements

• Document patient capacity with:

o All barriers to patient care in the NEMSIS element “eHistory.01—Barriers to Patient Care” (a

Required National Element of NEMSIS)

o Exam fields for “eExam.19—Mental Status” and “eExam.20—Neurological Assessment”

o Vitals for level of responsiveness and Glasgow Coma Scale

o Alcohol and drug use indicators

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

________________________ Go To TOC

Universal Care Rev. March 2022

Patient Refusals 25

Version 3.0

o Blood glucose level (as appropriate to situation and patient history)

• Patient Age

• Minors who are not emancipated and adults with a legal guardian: guardian name, contact, and

relationship

• Any efforts made to contact guardians if contact could not be made

• What the patient’s plan is after refusal of care and/or transport

• Who will be with the patient after EMS departs

• Patient was advised that they can change their mind and EMS can be contacted again at any

time

• Patient was advised of possible risks to their health resulting from refusing care and/or

transport

• Patient voices understanding of risks. A quotation of the patient’s actual words, stating they

understand, is best

• Reason for patient refusing care. A quotation of the patient’s actual words, stating they

understand, is best

• Medical direction contact

• Any assessments and treatments performed

Performance Measures

• Patient decision-making capacity was determined and documented

• Medical direction was contacted as indicated by EMS agency protocol

• Guardians contacted or efforts to contact the guardians for minor patients who are not or

cannot be confirmed to be emancipated

References

1. Patient Autonomy and Destination Factors in Emergency Medical Services (EMS) and EMS-Affiliated

Mobile Integrated Healthcare/Community Paramedicine Programs. Acep.org.

https://www.acep.org/globalassets/new-pdfs/policy-statements/patient-autonomy-and-

destination-factors-in-ems.pdf Revised October 2015. Accessed March 11, 2022

Revision Date

March 11, 2022

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

________________________ Go To TOC

Cardiovascular Rev. March 2022

Adult and Pediatric Syncope and Near Syncope 26

Version 3.0

Cardiovascular

Adult and Pediatric Syncope and Near Syncope

Aliases

Loss of consciousness

Patient Care Goals

1. Stabilize and resuscitate when necessary

2. Initiate monitoring and diagnostic procedures

3. Transfer for further evaluation

Patient Presentation

1. Syncope is heralded by both the loss of consciousness and the loss of postural tone and resolves

spontaneously without medical interventions. Syncope typically is abrupt in onset and resolves

equally quickly. EMS clinicians may find the patient awake and alert on initial evaluation

2. Near syncope is defined as the prodromal symptoms of syncope. The symptoms that can

precede syncope last for seconds to minutes with signs and symptoms that may include pallor,

sweating, lightheadedness, visual changes, or weakness. It may be described by the patient as

“nearly blacking out” or “nearly fainting”.

3. Rapid first aid during the onset may improve symptoms and prevent syncope

Inclusion Criteria

1. Abrupt loss of consciousness with loss of postural tone

2. Prodromal symptoms of syncope

Exclusion Criteria

Conditions other than the above, including:

1. Patients with alternate and obvious cause of loss of consciousness (e.g., trauma – See Head

Injury Guideline)

2. Patients with ongoing mental status changes or coma should be treated per the Altered Mental

Status Guideline

3. Patients with persistent new neurologic deficit [See Suspected Stroke/Transient Ischemic Attack

Guideline]

Patient Management

Assessment

1. Pertinent History

a. Review the patient’s past medical history including a history of:

i. Cardiovascular disease (e.g., cardiac disease/stroke, valvular disease, hypertrophic

cardiomyopathy, mitral valve prolapse)

ii. Seizure

iii. Recent trauma

iv. Active cancer diagnosis

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

________________________ Go To TOC

Cardiovascular Rev. March 2022

Adult and Pediatric Syncope and Near Syncope 27

Version 3.0

v. Dysrhythmias including prior electrophysiology studies/pacemaker and/or implantable

cardioverter defibrillator (ICD)

vi. History of syncope

vii. History of thrombosis or emboli

b. History of Present Illness, including:

i. Conditions leading to the event: after transition from recumbent/sitting to standing;

occurring with strenuous exercise (notably in the young and seemingly healthy)

1. Syncope that occurs during exercise often indicates an ominous cardiac cause.

Patients should be evaluated in the emergency department

ii. Patient complaints before or after the event including prodromal symptoms

iii. History of symptoms described by others on scene, including seizures or shaking,

presence of pulse/breathing (if noted), duration of the event, events that lead to the

resolution of the event

c. Review of Systems:

i. Current medications (new medications, changes in doses)

ii. Fluid losses (nausea/vomiting/diarrhea) and fluid intake

iii. Last menstrual period/pregnant

iv. Occult blood loss (gastrointestinal (GI)/genitourinary (GU))

v. Palpitations

vi. Unilateral Leg swelling, history of recent travel, prolonged immobilization, malignancy

d. Pertinent Physical Exam including:

i. Attention to vital signs and evaluation for trauma

ii. Note overall patient appearance, diaphoresis, pallor

iii. Detailed neurologic exam (including stroke screening and mental status)

iv. Heart, lung, abdominal, and extremity exam

v. Additional Evaluation:

1. Cardiac monitoring

2. Oxygen saturation (SPO

2

)

3. Ongoing vital signs

4. 12-lead EKG

5. Blood glucose level (BGL)

Treatment and Interventions:

1. Should be directed at abnormalities discovered in the physical exam or on additional

examination and may include management of cardiac dysrhythmias, cardiac ischemia/infarct,

hemorrhage, shock, etc.

a. Manage airway as indicated

b. Oxygen as appropriate

c. Evaluate for hemorrhage and treat for shock if indicated

d. Establish IV access

e. Fluid bolus if appropriate

f. Cardiac monitor

g. 12-lead EKG

h. Monitor for and treat arrhythmias (if present, refer to appropriate guideline)

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

________________________ Go To TOC

Cardiovascular Rev. March 2022

Adult and Pediatric Syncope and Near Syncope 28

Version 3.0

Patient Safety Considerations:

1. Patients suffering from syncope due to arrhythmia may experience recurrent arrhythmias and

should therefore be placed on a cardiac monitor

2. Geriatric patients suffering falls from standing may sustain significant injury and should be

diligently screened for trauma. [General Trauma Management Guideline]

Notes/Educational Pearls

Key Considerations

1. By being most proximate to the scene and to the patient’s presentation, EMS clinicians are

commonly in a unique position to identify the cause of syncope. Consideration of potential

causes, ongoing monitoring of vitals and cardiac rhythm and detailed exam and history are

essential pieces of information to pass on to hospital clinicians

2. For patients where a lower risk etiology is suspected, e.g., vasovagal syncope, decisions

regarding delayed or non-transport should be made in consultation with medical direction

3. High-risk causes of syncope include, but are not limited to, the following:

a. Cardiovascular

i. Myocardial infarction

ii. Aortic stenosis

iii. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (consider in young patient with unexplained syncope

during exertion)

iv. Pulmonary embolus

v. Aortic dissection

vi. Dysrhythmia

vii. Mitral valve prolapse is associated with higher risk for sudden death

b. Neurovascular

i. Intracranial hemorrhage

ii. Transient ischemic attack or stroke

iii. Vertebral basilar insufficiency

c. Hemorrhagic

i. Ruptured ectopic pregnancy

ii. GI bleed

iii. Aortic rupture

4. Consider high-risk 12-lead EKG features including, but not limited to:

a. Evidence of QT prolongation (generally over 500 msec)

b. Delta waves

c. Brugada syndrome (incomplete right bundle branch block (RBBB) pattern in V1/V2 with ST

segment elevation)

d. Hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy

Pertinent Assessment Findings

1. 12-lead EKG findings

2. Evidence of alternate etiology, including seizure

3. Evidence of cardiac dysfunction (e.g., evidence of congestive heart failure (CHF), arrhythmia)

4. Evidence of hemorrhage

5. Evidence of neurologic compromise

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

________________________ Go To TOC

Cardiovascular Rev. March 2022

Adult and Pediatric Syncope and Near Syncope 29

Version 3.0

6. Evidence of trauma

7. Initial and ongoing cardiac rhythm

Quality Improvement

Associated NEMSIS Protocol(s) (eProtocol.01) (for additional information, go to www.nemsis.org)

• 9914149 – Medical – Syncope

Key Documentation Elements

• Presenting cardiac rhythm

• Cardiac rhythm present when patient is symptomatic

• Any cardiac rhythm changes

• Blood pressure

• Pulse

• Blood glucose level (BGL)

• Symptoms immediately preceding event

• Patient status on EMS arrival: recovered or still symptomatic

Performance Measures

• Acquisition of 12-lead EKG

• Application of cardiac monitor

• National EMS Quality Alliance (NEMSQA) Performance Measures (for additional information,

see www.nemsqa.org )

o Stroke — 01: Suspected Stroke Receiving Prehospital Stroke Assessment

References

1. Anderson JB, Willis M, Lancaster H, Leonard K, Thomas C. The evaluation and management of

pediatric syncope. Pediatr Neurol. 2016; 55:6–13

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2015.10.018

2. Benditt DG, Adkisson WO. Approach to the patient with syncope. Cardiol Clin. 2013;31(1):9–25

3. Dovgalyuk J, Holstege C, Mattu A, Brady WJ. The electrocardiogram in the patient with

syncope. Am J Emerg Med. 2007; 25:688–701

4. Fischer J, Choo CS. Pediatric syncope: cases from the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin

North Am. 2010;28(3):501–16

5. Herbert M, Spangler M, Swadron S, Mason J. Emergency Medicine Reviews and Perspectives

(EM:RAP). C3 Continuous Core Content Podcast. Syncope – Introduction. November 2016.

https://www.emrap.org/episode/c3syncope/syncope. Accessed March 11, 2022

6. Huff JS, Decker WW, Quinn JV, Perron AD, Napoli AM, Peeters S, et al; American College of

Emergency Physicians. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult

patients presenting to the emergency department with syncope. Ann Emerg

Med. 2007;49(4):431–44

7. Kessler C, Tristan JM, De Lorenzo R. The emergency department approach to syncope:

evidence-based guidelines and prediction rules. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010;28(3):248–500

8. Khoo C, Chakrabarti S, Arbour L, Krahn AD. Recognizing life-threatening causes of

syncope. Cardiol Clin. 2013;31(1):51–66

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

________________________ Go To TOC

Cardiovascular Rev. March 2022

Adult and Pediatric Syncope and Near Syncope 30

Version 3.0

9. Orman R, Mattu A; Emergency Medicine Reviews and Perspectives (EMRAP). Spring Forward

into PE. Cardiology Corner – Syncope. March 2016.

https://www.emrap.org/episode/springforward/cardiology. Accessed March 11, 2022

10. Ouyang H, Quinn J. Diagnosis and management of syncope in the emergency

department. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010;28(3):471.485

Revision Date

March 11, 2022

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

________________________ Go To TOC

Cardiovascular Rev. March 2022

Chest Pain/Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS)/ST-segment Elevation Myocardial Infarction (STEMI) 31

Version 3.0

Chest Pain/Acute Coronary Syndrome (ACS)/ST-segment Elevation Myocardial

Infarction (STEMI)

Aliases

Heart attack Myocardial infarction (MI)

Patient Care Goals

1. Identify ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) quickly

2. Determine the time of symptom onset

3. Activate hospital-based STEMI system of care

4. Monitor vital signs and cardiac rhythm and be prepared to provide CPR and defibrillation if

needed

5. Administer appropriate medications

6. Transport to appropriate facility

Patient Presentation

Inclusion Criteria

1. Chest pain or discomfort in other areas of the body (e.g., arm, jaw, epigastrium) of suspected

cardiac origin, shortness of breath, associated or unexplained sweating, nausea, vomiting, or

dizziness. Atypical or unusual symptoms are more common in women, the elderly, and diabetic

patients. May also present with CHF, syncope, and/or shock

2. Chest pain associated sympathomimetic use (e.g., cocaine, methamphetamine)

3. Some patients will present with likely non-cardiac chest pain and otherwise have a low

likelihood of ACS (e.g., blunt trauma to the chest of a child). For these patients, defer the

administration of aspirin (ASA) and nitrates per the Pain Management Guideline

Exclusion Criteria

None noted

Patient Management

Assessment, Treatment, and Interventions

1. Signs and symptoms include chest pain, congestive heart failure (CHF), syncope, shock,

symptoms similar to a patient’s previous MI

2. Assess the patient’s cardiac rhythm and immediately address pulseless rhythms,

symptomatic tachycardia, or symptomatic bradycardia [See Cardiovascular

Section and Resuscitation Section]

3. If the patient is dyspneic, hypoxemic, or has obvious signs of heart failure, EMS clinicians

should administer oxygen as appropriate with a target of achieving 94–98% saturation

[Refer to Universal Care Guideline]

4. The 12-lead EKG is the primary diagnostic tool that identifies a STEMI; it is imperative that

EMS clinicians routinely acquire a 12-lead EKG within 10 minutes for all patients exhibiting

signs and symptoms of ACS

NASEMSO

National Model EMS Clinical Guidelines

________________________ Go To TOC