CONCEPT NOTE

Online Examinations in

Emergency Contexts

Are Proctoring and Other Technologies Feasible in Syria to

Facilitate Inclusive School Exams for All?

SEPTEMBER 2022

Authors

Thaer AlSheikh Theeb, Aynur Gul Sahin, Salma Abdelrahman, Rachel Chuang (EdTech Hub),

Friedrich Affolter, Bayan Al Mekdad, Rani Sabboura, Yazeed Sheqem (UNICEF)

Reviewers

Caitlin Moss Coflan, Björn Haßler (EdTech Hub)

Acknowledgments

This paper was born out of a series of technical meetings and consultations called for by

UNICEF Education Section at Syria Country Office, with colleagues from Education Sections

at UNICEF’s Middle East and Northern Africa Regional Office and UNICEF Headquarters in

New York. We would like to express our gratitude to Bo Viktor Nylund (Syria Country Office

Representative), Ghada Kachachi, Paola Retaggi, Brenda Haiplik, Hind Omer, Linda Jones,

Neven Knezevic and Juan Pablo Giraldo Ospino who in the early phases of this project helped

with the identification of successful practices for implementing crossline-, crossborder- and

online exam modalities in crisis-affected contexts.

The team would also like to thank Kyle Arthur for the design of this paper.

Disclaimer

The statements in this publication are the views of the authors and contributors and do not

necessarily reflect the policies or the views of UNICEF or EdTech Hub.

Recommended citation

AlSheikh Theeb, T., Sahin, A. G., Abdelrahman, S., Chuang, R., Affolter, F., Al Mekdad, B.,

Sabboura, R., & Sheqem, Y. (2022). Online Examinations in Emergency Contexts: Can

Proctoring and Other Technologies Be Feasible Alternatives for Facilitating Inclusive School

Exams for All in Emergency Contexts? EdTech Hub, UNICEF. https://doi.org/10.5281/

zenodo.6929534. Available at https://docs.edtechhub.org/lib/T9NZ63T3.

Licence

Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

You — dear readers — are free to share (copy and redistribute the material in any medium

or format) and adapt (remix, transform, and build upon the material) for any purpose, even

commercially. You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate

if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that

suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.

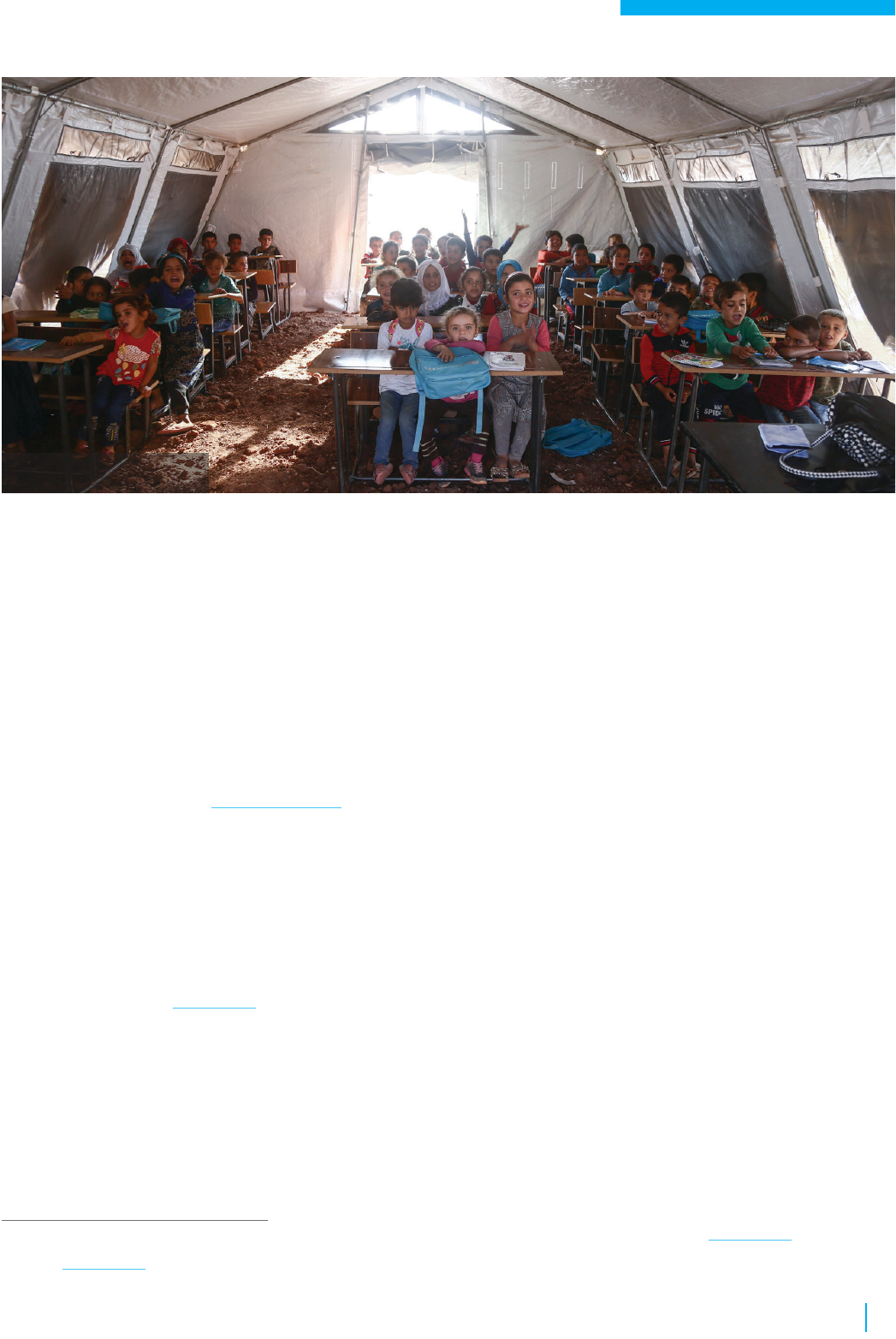

Cover photo: © UNICEF Syria/2019/Aldrobi

Online Examinations in Emergency Contexts

1

CONTENTS

Abbreviations and acronyms ............................................................................................................................ 2

Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................... 3

1. Purpose of this document .............................................................................................................................4

2. Overview of online examinations and proctoring ....................................................................................4

2.1. Definitions linked to online examinations ................................................................................................................4

2.2. A short history of online examinations ....................................................................................................................4

2.3. Comparing national examinations and other assessments .......................................................................................5

2.4. Definitions linked to proctoring technologies ...........................................................................................................6

3. Opportunities and risks of online examinations in emergency contexts ............................................... 7

3.1. Recap of Research ...................................................................................................................................................8

3.1.1. Flexibility and inclusion .................................................................................................................................................. 8

3.1.2. Costs ............................................................................................................................................................................. 9

3.1.3. Fraud prevention ......................................................................................................................................................... 10

3.1.4. Ethical and legal concerns .......................................................................................................................................... 13

3.2. Adapting to a new examination modality ...............................................................................................................13

3.2.1. Transitioning to online examinations ........................................................................................................................... 13

3.2.2. Digital literacy ............................................................................................................................................................. 14

4. Pre-assessment tools ................................................................................................................................... 15

4.1. Feasibility criteria ................................................................................................................................................... 15

4.2. Cost analysis .........................................................................................................................................................22

5. Conclusions ................................................................................................................................................... 26

References .........................................................................................................................................................27

Annex A ..............................................................................................................................................................30

Online Examinations in Emergency Contexts

2

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

AP Advanced Placement

CAA Computer-Assisted Assessment

CBA Computer-Based Assessment

C4D Communication for Development

ERC Emirates Red Crescent

ERT Emergency Remote Teaching

GoS Government of Syria

GRE Graduate Records Examination

IB International Baccalaureate

MBRGI Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum Global Initiatives

MoE Ministry of Education

OER Open Educational Resources

PIRLS Progress in International Reading Literacy Study

PISA Programme for International Student Assessment

SAAT Standard Achievement Admission Test

TOEFL Test of English as a Foreign Language

To T Training of Trainers

TVET Technical and Vocational Education and Training

TIMSS Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study

UBC University of British Columbia

UCLES University of Cambridge Local Examinations Syndicate

WASSCE West African Senior School Certificate Examination

Online Examinations in Emergency Contexts

3

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Natural and man-made disasters, and most recently

the Covid-19 pandemic, have highlighted the role that

remote and hybrid learning play in education delivery, as

well as the need to reimagine the educational practices

appropriate in emergency contexts.

1

While there has

been a rise in online learning, digital assessments

and e-proctoring platforms in high-income countries,

questions remain as to the feasibility of online

examinations in disaster-prone emergency situations.

In Syria, 11 years of conflict and economic shocks, as

well as a fracturing of administrative control of education

services across the country, have hindered the access

of students wishing to participate in the Syrian national

9th Grade and 12th Grade exams. These challenges

pose the question of whether online examinations could

be an option that facilitates access to exams for more

students in an emergency context such as Syria’s. At

the same time, any attempt to explore the feasibility of

online examinations in Syria must consider how 11 years

of conflict, poverty, and economic shocks have destroyed

and battered basic infrastructure, power plants, and

ICT infrastructure. Most Syrian families cannot afford

ICT devices and have been deprived of opportunities

to acquire digital literacy skills for more than a decade.

Overall, the country has been unable to develop digital

support systems for teachers and students. All these

factors add layers of complexity to implementing online

high-stakes examinations.

The purpose of this document is to serve as a guide that

education practitioners working in emergency contexts

can use to assess the feasibility of implementing online

examinations and using proctoring technologies. The

Syrian crisis will be referenced as an example case

in order to illustrate opportunities despite significant

constraints and dilemmas. After a review of relevant

definitions and context (Section 2), the document

provides a summary of the opportunities, risks, and

constraints associated with online examinations and

proctoring (Section 3). The document also includes criteria

which decision-makers can use to determine whether

online high-stakes examinations are suitable for their

context and the investments needed to warrant the

results (Section 4).

The document concludes that the implementation

of online high-stakes examinations in Syria and other

emergency contexts will require significant investments

in achieving the prerequisites needed for feasibility and

credibility (Section 5). Prerequisites include electricity,

internet, and devices, as well as the development of the

digital skills necessary for students to participate in online

exams and for teachers and administrators to facilitate

online exams. Further efforts are needed to prevent

leakage of information on exam questions and content,

and promote cultural change around online examinations.

In the event that decision-makers choose to implement

online high-stakes examinations (in Syria and other

education emergency contexts), the document

recommends the use of an iterative approach, where

online examinations are first piloted with a subset of

students and schools prior to scaling up nationally.

1

Emergencies are defined by INEE Minimum Standards as ‘a situation where a community has been disrupted and has yet to return to stability’ (INEE, 2010). Categories of emergencies

include: conflict settings, epidemics and natural disasters (Ashlee et al., 2020).

Online Examinations in Emergency Contexts

4

1. PURPOSE OF THIS DOCUMENT

2. OVERVIEW OF ONLINE EXAMINATIONS AND PROCTORING

This document was produced in response to a request

from the UNICEF Syria team that was submitted to the

EdTech Hub Helpdesk in January 2022. The UNICEF team

requested support to assess the feasibility of implementing

online examinations and proctoring technologies in

emergency contexts, in order to provide guidance in the

form of lessons learned and good practices for the Syrian

context.

For the first phase of this request, EdTech Hub conducted a

rapid scan of EdTech companies around the world focused on

online examination technologies. The exercise compiled 18

companies that have partnered with Ministries of Education

(MoEs) (for high-stakes examinations), universities (for online

testing) and / or business companies (for staff assessments).

A table of MoE partner companies and proctoring tools is

provided in Annex A. For the second phase, EdTech Hub

developed this document which delves further into the topic

of online examinations in emergency contexts.

2.1. DEFINITIONS LINKED TO ONLINE

EXAMINATIONS

This section discusses definitions linked to online

examinations, provides a short history of online

examinations (comparing national examinations and other

assessments), and finally offers definitions linked to

proctoring technologies.

A computer-based assessment (CBA) can be defined

as an assessment that is delivered and marked by a

computer. Online examinations form a subset of CBAs

and can be defined as “examinations administered

via the internet” (Barkley, 2002). There are a number

of ways to classify online examinations. Often, online

examinations are categorised according to the modality

of their implementation into home-based and lab-based,

depending on the location where the online examination

is administered. While lab-based online examinations

require learners to be physically present in a designated

centre where the test is administered, home-based online

examinations can be taken in any location, provided that

the learner taking the examination has a device to use (e.g.,

a laptop or a tablet) and that the examination location has

access to the internet and to electricity. A number of high-

stakes examinations also have home-based online versions.

Examples include the Graduate Records Examination

(GRE), the Advanced Placement (AP) exams, and the Test

of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) exam (Luna-

Bazaldua et al., 2020). Questions remain, however, as to the

feasibility of administering home-based online examinations

in emergency contexts.

Lab-based examinations allow learners to take a digital form

of the examination while being proctored by an observer;

sometimes proctors can also monitor each other to ensure

that observers are not providing illegitimate assistance

to learners. This is of special importance in the context of

high-stakes examinations, or assessments which are

statutory and / or whose results are important to both the

authority administering the examination and the learners.

Oftentimes, the outcomes of the high-stakes examination

affect learners’ progress to the next phase of their

education or career.

Understandably, authorities have generally been interested,

but at the same time also reluctant, to transform high-

stakes examinations into digital form. Authorities are

attracted by the opportunity to reach children who lack

access to exam centres and by the possibility of digitally

collecting exam data and managing exams. On the other

hand, governments worry about viruses causing system

interruptions, possible leakages of exam questions prior

to the exams, and the fact that protection against hackers

ultimately cannot be guaranteed. Governments may also be

aware that infrastructure is not equally available, and that a

lack of funds prevents the remedying of infrastructure gaps.

2.2. A SHORT HISTORY OF ONLINE EXAMINATIONS

Many have been hopeful that examinations can be

automatised and made interactive, leading to savings in

time and effort and to better engaging learners, since

even before the development of the first computers in the

1970s. Yet despite the initial optimism, computer-based

assessments remain underutilised, even in high-income

countries not affected by disasters. The 2000s witnessed

© UNICEF Syria/2022/Shahan

Online Examinations in Emergency Contexts

5

the development of a number of on-screen tests which

use automated marking to evaluate learners’ answers to

standardised multiple-choice questions, as well as other

e-assessment tools that use a wider range of question

types and incorporate interactive media elements (Oldfield

et al., 2012).

The Covid-19 pandemic has arguably provided the biggest

impetus yet for moving examinations online. In response

to the pandemic, a number of testing organisations began

offering online versions of the examinations they administer

(e.g., GRE, AP exams, and the TOEFL). Some states in

the United States, most notably California, decided to

move professional certification exams to an online format

(Luna-Bazaldua et al., 2020). In Saudi Arabia, its high-

stakes Standard Achievement Admission Test (SAAT) was

moved from a paper-and-pencil format to online following

school closures in 2020 (ETEC, 2020); “this move was

possible due to investments made over previous decades

in infrastructure and expertise for assessments, plus careful

planning and communication for the new system and its

roll-out” (Al-Qataee et al., 2020). While the discussion

around online examinations, in response to the pandemic,

focuses on the use of online examinations in emergency

contexts, the discussion unquestionably takes high-

income countries as its focus. The authors are not aware

of examples of the use of online assessments in low- and

middle-income, crisis-affected countries.

2.3. COMPARING NATIONAL EXAMINATIONS AND

OTHER ASSESSMENTS

Currently, there are a number of global and national

assessments that are already being offered or will be

offered in a digital format:

• The Programme for International Student

Assessment (PISA), which is used at both the national

and the international level to inform education policy

decisions, is a two-hour computer-based exam for

15-year-olds which primarily consists of multiple-choice

questions. Starting in 2015 for most countries, PISA

was delivered as computer- and lab- based assessments

(OECD, no date). In 2018, PISA was delivered to

around 600,000 learners across 79 countries (Andreas

Schleicher, 2018).

• The International Association for the Evaluation of

Educational Achievement (IEA), which has been

administering its Progress in International Reading

Literacy Study (PIRLS) examination to fourth graders

every five years since 2001, decided to also offer a

digital option of its 2021 examination, in addition to the

option of the paper-based version. The digital version,

called digitalPIRLS, “will be offered as a web-based

system via school-based or IEA web servers, or via a

USB drive connected locally to a PC with the Windows

Operating System” (TIMSS & PIRLS International Study

Center, 2022). In total, around “319,000 students,

310,000 parents, 16,000 teachers, and 12,000

schools participated” in PIRLS 2016 (TIMSS & PIRLS

International Study Center, 2019).

• The Trends in International Mathematics and

Science Study (TIMSS), an examination that has been

administered since 1995, began a transition to becoming

to a computer-based assessment in 2019 which is

expected to be completed in 2023, when TIMSS will

be available for delivery “online or locally using USB

sticks or a local server,” and with each country where

the test will be administered deciding if to “use school

equipment or bring equipment into schools” (IEA,

2022). Around 4,000 learners participated in TIMSS 2019

(TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center, 2019).

• The SAT exam, widely used to make college admissions

decisions in the United States, will move to a digital

format in 2023 internationally and in 2024 in the United

© UNICEF Syria/2021/Khudur

Online Examinations in Emergency Contexts

6

States. The digital SAT will not be home-based, however,

even though learners will be allowed to use their own

devices if they so choose. Instead, the digital SAT will

be administered in proctored schools or test centres

(Nadworny, 2022; Moon, 2021). In 2021, one and a

half million learners to the SAT exam, down, no doubt

because of the pandemic, from 2.2 million in 2020 (The

College Board, 2021).

Significant differences exist between standardised

tests like the SAT, which largely include multiple-choice

questions, and high-stakes national examinations, which

can include a broad mix of questions that are more

open-ended (e.g., a biology question that asks a learner

to draw a cell) in addition to multiple-choice questions.

Multiple-choice questions can be evaluated against

objective criteria, which means that “the response can

be marked right or wrong without the need for expert

/ human judgement” (JISC, 2006). The digital skill set

required for multiple choice questions is thus relatively

straight forward. Notwithstanding, the needed aptitudes

and practical abilities – for composing digitized in-depth

responses that demonstrate an in-depth understanding of

an academic subject; or for digitally drawing a cell structure

as part of a biology exam – are much more sophisticated.

They require advanced knowledge and experience for

navigating particular and often costly software and hardware

modalities. As a result, an assessment with mostly multiple-

choice questions will be better suited to an online format

than an assessment with mostly open-ended questions.

2.4. DEFINITIONS LINKED TO PROCTORING

TECHNOLOGIES

The proctoring of exams has traditionally been done

by a trained individual who is physically present in the

examination hall or classroom. With the development of

online examination technology, proctoring technology was

also developed to ensure the validity of online exams.

Remote proctoring is a proctoring method that “allows

students to take an assessment at a remote location while

ensuring the integrity of the exam”; it involves “the use of

software to monitor students during the administration of

remote exams and assessments” (Eckenrode et al., 2016;

Parghi et al., 2021).

“Online proctoring is a form of location-independent

digital assessment. The invigilation takes place

online using special software. Online proctoring

software promises to allow students and course

participants to sit their exams anywhere (for

example at home) in fraud-resistant conditions

and / or with invigilation against fraud. Monitoring

software, video images and the monitoring of

students’ screens should prevent them from

engaging in fraud.”

- SURF, 2020

There are different types of proctoring for remote online

examinations; these include live proctoring and automated

proctoring. Live proctoring entails an invigilator (also

known as a proctor) watching test takers to ensure no

fraud is committed; this proctoring method is used by

platforms like Examity and ProctorU. For example, the

University of Mississippi uses ProctorU “to allow its

students to “take an exam wherever they choose (in a

residence hall or apartment, for example)” (Chin, 2020;

Eckenrode et al., 2016). Live proctoring can take the form

of live supervision, where lecturers themselves watch

test takers through a conferencing software. Alternatively,

a special software which “allows someone to watch and

intervene during the exam” can be used for proctoring

online examinations (SURF, 2020). Another form of remote

“live” proctoring involves the recording of each examination

so that it can be watched at a later stage by an invigilator

(SURF, 2020).

Automated proctoring involves the monitoring of test

takers through machine learning and facial recognition,

among other technologies; this is used by platforms like

Proctorio (Chin, 2020). Instead of proctors monitoring or

reviewing the entire exam, automated proctoring allows

for the use of a specialised software to identify specific

moments of potential fraud or suspicious behaviour which

a reviewer can watch again in order to assess whether

they indeed constitute suspected fraud (SURF, 2020).

Online examinations proctoring can also utilise a lockdown

mechanism which can be “used to prevent students from

accessing web browsers or other applications” (Eckenrode

et al., 2016).

© UNICEF Syria/2019/Aldrobi

Online Examinations in Emergency Contexts

7

3. OPPORTUNITIES AND RISKS OF ONLINE EXAMINATIONS IN

EMERGENCY CONTEXTS

Education emergencies can have a number of causes which

impact the specific shape that they take. These causes

can range from biological hazards (e.g., as a consequence

of a global pandemic such as the Covid-19 pandemic) and

economic shocks, to climate changes and armed conflict,

which “can disrupt the delivery of education services and

cause destruction or damage to education infrastructure in

the short — and long-term” (Ashlee et al., 2020).

In Syria — the country example chosen for this report as a

case in point for illustrating the feasibility and constraints of

proctored online examination in emergency settings — all of

these above crisis factors are at play, leading to challenges

surrounding the lack of ICT infrastructure such as stable

electricity and internet, the lack of devices at home, low

levels of digital literacy of students, teachers and school

administrators, and the limited systems of support for

teachers and students (UNDP, 2022).

A survey conducted by the Norwegian Refugee Council

(NRC) highlighted that 89% of families with students in

formal education in Syria do not have access to laptops,

desktops, or tablets.

2

With millions of children reported still

out of school, or having missed out on education for months

and even years, it is obvious that digital skills are mostly

lacking across student populations with the exception of

a small minority of privileged children. The challenges are

compounded for those student populations living in isolated

regions since national exams are only offered in those

areas where the Government of Syria (GoS) is in effective

control, whereas students who live in areas outside of

government control need to travel far to access government

exam centres. Furthermore, some platforms and learning

resources are not available in Syria (e.g., Zoom, Google

workspace, Coursera) due to sanctions and the need to

comply with US export regulations (NRC and UNICEF, 2022,

forthcoming).

3

In 2021, Syrian national exams were conducted as paper-

and-pencil exams, as they have been for decades. Syrian

national exams are conducted once a year in the months

of May and June, for 9th and 12th graders. Other grades

examinations take place two to three weeks prior to

9th and 12th grade exams. 9th and 12th grade exams

are considered to be milestone exams as they decide

on whether a student is allowed to continue her or his

education pathway to universities or mid-level continuing

education programmes such as technical and vocational

training (TVET), tourism schools, and sport education

programmes. Passing these milestone exams is therefore

‘a must’ for a student; and high-achievers will be able to

enroll in universities offering programmes such as medicine

and engineering that offer enhanced career prospects. The

top ten 12th graders attending TVET programmes likewise

have the opportunity to enroll into corresponding university

programmes.

2

Note that the survey did not capture access to mobile devices. In 2020, there were 95 mobile cellular subscriptions reported per 100 people in Syria (World Bank, 2020). This data suggests

that mobile devices may serve as an alternative channel for learning in the country.

3

However, Learning Passport, a platform with global and local learning resources developed by UNICEF and Microsoft, has been made available in Syria. This marks an important success

story in light of sanctions.

© UNICEF Syria/2019/Aamer

Online Examinations in Emergency Contexts

8

Exams for both 9th and 12th graders usually last 3-4

weeks, with only one subject exam per day, all of them

administered in the presence of teachers, and scheduled

in time intervals of one to three days. Each exam lasts a

minimum of an hour and a half, but some exams can also

last for up to three and a half hours. Students whose upper-

secondary specialisation is Sciences are tested in up to

eight science subjects, whereas those specialising in the

humanities take up to seven humanities subject tests. Once

exams are completed, students wait for the announcement

of results through the Ministry. The results are published

online, usually a month after the exams. Depending on the

results, students who are disappointed with their grades

are invited to take the examinations again, but only in three

subjects, and are usually allowed to do so only within a

period not exceeding a maximum of two weeks after the

first round of exams.

Given that Syria has some geographic areas that are not

under the control of the GoS, and with separate non-

coordinated education authorities as a consequence of

the crisis, the Ministry of Education (MoE) with support

from UN and civil society agencies developed a system

of ‘national exam accommodation centres’ – for so-called

‘crossline children’ that need to travel from areas not under

GoS control into areas where national GoS exam centres

are operating. Crossline children travel to GoS exam

centres and stay in accommodation centres. From there,

crossline children visit schools that host national paper-and-

pencil exams which are supervised, in specially arranged

classroom settings, by teachers who are appointed by the

MoE. Although the number of crossline children registering

for exams annually is around 16,000, in recent years the

number of crossline children attending national exams has

been between 6000 and 7000.

3.1. RECAP OF RESEARCH

This section compiles discussion and research on the

opportunities and risks surrounding online examinations

and e-proctoring, and the ability to administer credible

examinations (Ironsi, 2021) across several areas:

1. Flexibility and inclusion

2. Costs

3. Fraud prevention

4. Ethical and legal concerns

5. Adapting to a new examination modality

6. Digital literacy

3.1.1. FLEXIBILITY AND INCLUSION

Globally, many high stakes examinations were cancelled

in 2020 due to Covid-19 including the SATs, International

Baccalaureate (IB) exams, and state-wide national exams

such as in Uttar Pradesh in India (Liberman et al., 2020). In

some cases, exams were postponed, as was the case for

national exams in Colombia and the West African Senior

School Certificate Examination (WASSCE) (Liberman et al.,

2020).

In other scenarios, online assessment and proctoring

technologies have allowed learning to proceed undisrupted

during prolonged school closures (Ironsi, 2021; Ferri et al.,

2020; Luna-Bazaldua et al., 2020; Liberman et al., 2020).

The flexibility that these technologies provide to educational

institutions creates an option for learning and assessment

to continue even when face-to-face learning cannot, and

means that exams can be administered at any time and in

any place (SURF, 2020). This allows educational institutions

to provide learners with opportunities regardless of where

learners are located around the world, which enables

benefits for more students, especially those based outside

of their country of citizenship (SURF, 2020). Further, online

examinations allow for the possibility that learners may

take examinations at times of their choosing, which fits well

with a trend in education that aims to place learners at the

centre of educational decision-making (SURF, 2020).

Online examinations pose challenges of their own in terms

of equity and the inclusion of all learners. The feasibility of

online examinations depends on the availability of electronic

devices and access to the internet for the test-takers (as

well as the invigilators in the case of e-proctoring; Ironsi,

2021). Online examinations, then, will not be accessible

to all learners given the existing inequities in access to

technology. Even learners who have access to appropriate

digital infrastructure to support online examinations might

not have the appropriate space at home to be able to take

the test in appropriate exam conditions or possess the

digital literacy skills to take online examinations (Luna-

Bazaldua et al., 2020).

© UNICEF Syria/2020/Aldroub

Online Examinations in Emergency Contexts

9

In Syria’s context, the vast majority of learners lack access

to technology at home and have never owned a computer,

let alone have the privilege of a designated space at

home suitable for online examinations. This adds a layer

of inequity to the examination process and leads to the

marginalisation of learners whose circumstances (e.g.

socio-economic background, large families, geographical

location) mean they have limited access to and engagement

with the required technology for online learning and

assessment. In fact, relying solely on online examinations

carries a real risk of further exacerbating inequities, whether

these be financial inequities or inequities in access to

needed infrastructure. Financial and accessibility inequities

can thus become even more geographically concentrated if

online examinations are used uncritically. Other than access

to digital devices, the use of online assessments also poses

the risk of exclusion of learners with special educational

needs and disabilities (SEND; Luna-Bazaldua et al., 2020).

A multitude of complexities surrounding online

examinations for learners with SEND should be

acknowledged. In general, an inadequate focus on ensuring

that online examinations are designed and delivered in such

a way as to meet the needs of learners with SEND will, in

all likelihood, result in the further marginalisation of learners

with SEND. Additional in-person support, supplemented

by the use of EdTech tools (e.g, assistive technologies

with features including text to speech and on-screen

magnification), can potentially play a role in meeting the

needs of learners with SEND during test-taking procedures

(Coflan & Kaye, 2020).

The extent to which these risks can be mitigated will

always depend on the specific context in which they

present themselves. In Italy, for example, initiatives to

donate devices, as well as efforts to direct funds to give

students devices, were launched in an effort to mitigate

the risk of uneven access to technology exacerbating

inequality (Ferri et al., 2020). In the context of a country

undergoing a humanitarian crisis, such as Syria, however,

inequities tend to be especially pronounced: children from

less war-affected areas, or from better-off families, will have

better opportunities than children from poor or displaced

families to develop digital literacy skills, and urban areas

are technologically better equipped than rural areas. What’s

more, depending on the political support networks available

in different regions, some areas fare better or worse when

it comes to access to technology.

3.1.2. COSTS

Whether online examinations cost more or less than

in-person alternatives varies depending on many

factors, including the administering institution, the study

programme, and the specific situation in the country where

the tests are administered (SURF, 2020). In high-income

countries that are not affected by natural or man-made

disasters, the availability of online learning and assessment

options, especially in higher education, has created

opportunities to reduce costs of education for learners,

with learners in some cases taking online courses that

are available for free and thus only needing to pay for the

examinations, which allows learners to save on tuition,

© UNICEF Syria/2019/Aamer

Online Examinations in Emergency Contexts

10

textbooks, and school-related living expenses (Ferri et al.,

2020). This is obviously not the case for learners in low- and

middle-income countries where many learners cannot even

afford textbooks or stationery and thus will not be saving

on costs (which they already do not incur). The costs for

learners, however, is only one cost among many, and one of

the risks to online examinations in emergency contexts is

their limited cost-effectiveness for authorities administering

the examinations, due to high overarching costs. Evidence

supports that online proctoring technologies are more

expensive than in-person exams, whether in schools or

universities (SURF, 2020). To begin with, there is the cost

of the infrastructure, including devices for test-taking which

needs to be in place for online examinations.

In Syria, for example, costing requires consideration of the

crisis-produced dilapidation of infrastructure, the country’s

loss of digital learning and investment opportunities

when compared with countries not affected by conflict,

sanctions and economic shocks. Therefore, any kind of

costing structure must consider infrastructure, hardware,

software, and possibly satellite technology to provide

Internet to particular isolated locations where phone lines

and cellular networks are not available,

4

as well as digital

skills development and administration expenditures, which

eventually need to be scaled up across the country.

In addition, authorities need to consider the costs of

e-proctoring tools, which are often too high for most

educational institutions to afford (Ironsi, 2021). Other costs

include those required to transform and develop content

4

An organisation that has experimented with the provision of satellite technology for isolated or crisis-affected areas in need of digital education content is the Mohammed bin Rashid Al

Maktoum Global Initiatives (MBRGI) in support of its e-learning platform Madrasa.

that is suitable for online delivery, and the cost of hiring and

training personnel (such as remote proctors) (Luna-Bazaldua

et al., 2020). For the physical monitoring of school-based

exams, schools may wish to use their own facilities and

their own staff as invigilators; online proctoring, on the

other hand, would require additional fees that are often

more expensive (SURF, 2020). In Syria, schools all over the

country lack not only these facilities themselves but also

the capacity to maintain and administer them. Therefore

in Syria, substantial investment would be required either

to create the facilities necessary for physical monitoring

of school-based exams, or to develop online proctoring

systems.

Please see Section 4.2 for a cost analysis template tailored

to help emergency education practitioners to plan and

budget for proctored online examinations.

3.1.3. FRAUD PREVENTION

A significant challenge with online examinations is ensuring

their validity, transparency, and reliability. While fraud and

cheating arguably also occur during in-person examinations,

educational institutions tend to have more experience in

administering in-person examinations and “are thus capable

of making a relatively good assessment of the associated

risks” (SURF, 2020). This is not the case with online

proctoring, with which educational institutions “have not

yet built up the same level of experience” (SURF, 2020). In

addition, since “each supplier uses different methods and

technologies … the experiences of one institution may not

© UNICEF Syria/2019/Aldrobi

Online Examinations in Emergency Contexts

11

always be directly applicable to other institutions” (SURF,

2020). This points to a lack of information as to whether

online examinations can in fact be administered in such a

way as to successfully prevent cheating.

One of the main strategies to address these challenges is

the use of e-proctoring software (Ironsi, 2021). E-proctoring

software uses tools such as accessing the test takers’

microphones and webcams during the examination, facial

recognition software, screen sharing (which allows the

proctor to view the test taker’s screen), lock-down browsers

(special browsers to prevent test takers’ access to other

browsers or applications during the examination), AI

software to detect cheating, and even keystroke dynamics

(which, by analysing how test takers type their answers,

can be used to issue a warning if someone is suspected

of impersonating a test taker) (Ironsi, 2021; SURF, 2020).

While “fraud involving manipulation of hardware or software

can usually be detected … this often has far-reaching

implications for student privacy” (SURF, 2020). Moreover,

AI software needs time to learn the different ways in which

cheating can take place in different contexts, and thus

cannot be counted on to be fully effective in detecting

cheating from its first deployment.

An examination of the literature on the topic found that

80% of the e-proctored online examinations being surveyed

showed evidence of malpractice (Ironsi, 2021). Further,

the ability of artificial intelligence software to detect and

identify cheating is questionable (Ironsi, 2021). Automated

reviewing of positive fraud detection is much less accurate

than live proctoring; an invigilator can more accurately

identify if a certain movement by the test taker is indicative

of fraud or not (SURF, 2020). Instances of false positives,

or the indication of a suspicion that an instance of fraud or

cheating has been committed when in fact none has been,

are much more likely to occur with automated proctoring

compared to online live proctoring and in-person proctoring;

“with recordings, it is impossible to be sure whether a

student was trying to cheat or whether they just glanced

away from the screen” (SURF, 2020).

The scalability of fraud and cheating is substantially

increased in online examinations. “As soon as a student

has developed software to make it possible to commit

fraud, they could pass it on to a large group of students

in the blink of an eye” (SURF, 2020). The heightened use

of online proctoring technologies increases the chances

that some software will be developed to bypass them.

Unless an education institution has some control over the

space where an examination is conducted, “fraud can be

committed in ways that are (almost) impossible to detect”

and the list of possible ways to do so “is almost endless”

(SURF, 2020). While control mechanisms such as webcams

can reduce the risk of fraud and cheating, they cannot

eradicate that risk entirely (SURF, 2020).

Another set of challenges of online examinations are not

caused by proctoring risk factors. Nevertheless, challenges

relating to the storing and sharing of the content of online

examinations, as well as challenges related to the reporting

of cheating incidents, are significant to preserve the validity

of online examinations. However, it is worth noting that

exam questions can be leaked for both online and paper

examinations. Mechanisms and protocols must be in place

to prevent teachers, administrators, or other persons who

have access to an exam’s content from leaking the exam’s

questions and thus jeopardising its validity. Randomised

monitoring visits, most ideally by third-party monitors, and

the requirement that proctors fill a daily report detailing

instances of suspected cheating or fraud can be effective

mechanisms to ensure that proctors in test centres are

appropriately reporting cases of suspected malpractice.

In the eventuality that a student is suspected

to have committed fraud, Ministries need a

protocol for reporting a suspected fraudulent

behavior, keeping in mind that students cannot

be charged with cheating unless a case was duly

reported and the suspicion has been reviewed

by the education authorities, and relevant action

has been recommended in line with policies and

procedures. A suggested reporting template is

enclosed under Annex B.

© UNICEF Syria/2020/Belal

Online Examinations in Emergency Contexts

12

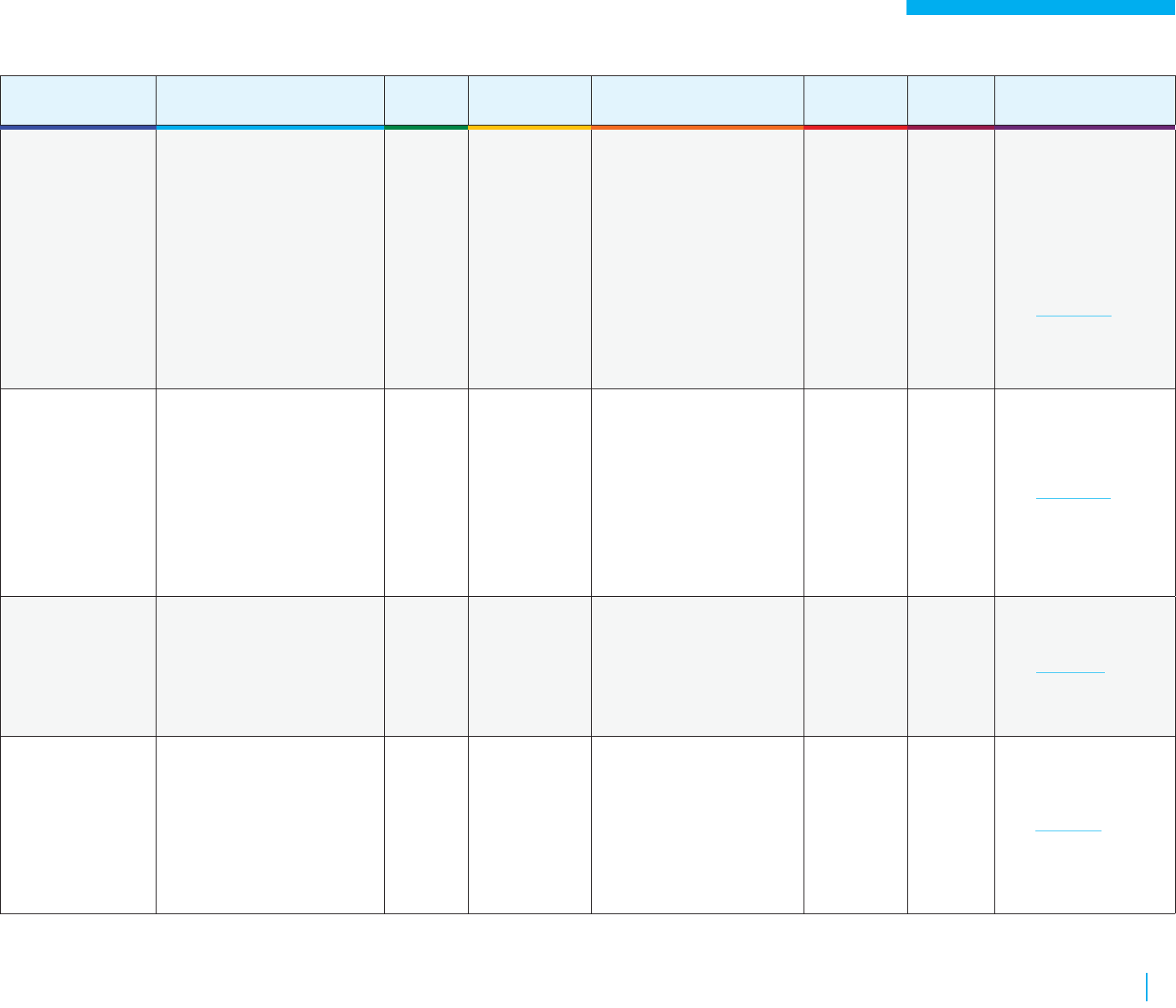

Online proctoring risk factors Description Possible countermeasures

An extra browser or tab

A student attempts to search for answers

online during an examination

Monitoring by proctors; screen captures, an

extra webcam, and a good lock-down browser

Another person in the

room

A student looks at the answers of others

or tries to consult with them (verbally or

nonverbally)

Lab-based examinations: Dividers / screens

between desks

Home-based examinations: Microphone,

cameras

5

Hidden crib sheets

A student uses crib or cheat sheets; this also

can be a regular occurrence during in-person

examinations

Lab-based examinations: Proctors can keep

an eye out for the use of crib sheets

Home-based examinations: cameras

(however, in these situations, “the room will

never be fully visible during the exam, and

hidden crib sheets remain a possibility”)

Someone else using the

PC

A student has another individual take the

exam for them

Identity verification, through showing a

student card or ID to an invigilator or to the

webcam

A second person

monitoring or controlling

the PC

A student gives another individual remote

access to their computer. The other person

can see their screen and control the keyboard

and mouse

Lab-based examinations: Proctors can see

student’s keyboard and mouse and check if

movements match what is happening on the

screen; it would also be more difficult for

a student to use a shared computer in the

testing centre to grant remote access

Home-based examinations: Logging software

that identifies external connections to the

computer

Software that provides

answers

A student installs software that scans the

questions on the screen and looks up the

answers. The software could show these

on the screen, or possibly even fill them in

directly

Lab-based examinations: Similar to the risk

factor above, proctors can see student’s

keyboard and mouse and check if movements

match what is happening on the screen; it

would also be more difficult for a student to

install software on a shared computer in the

testing centre

Home-based examinations: Logging software

that identifies external connections to the

computer

Table 1. Online proctoring risk factors and possible countermeasures to them (SURF, 2020)

5

Students are often asked to show the entire room to the camera prior to the start of the examination. However, a second person could hide outside of the camera’s field of view.

Moreover, it is essential that the reporting of cheating cases

is done professionally to ensure that no harm or abuse is

done to children. In some cases, teachers and proctors

may not be aware of established protocols to follow when

reporting cheating cases. While children must not be

harmed when cheating is being reported, some aspects of

this potential harm and how to mitigate it (e.g., the power

which a proctor who has caught a learner cheating has) are

culturally specific and must be dealt with in a way that pays

attention to the local context.

Online Examinations in Emergency Contexts

13

3.1.4. ETHICAL AND LEGAL CONCERNS

Ethical concerns related to data collection and sharing,

monitoring the biometric identities of test takers, and

accessing test takers’ audio and cameras are all issues

related to the privacy of the test takers. This calls for a

revaluation of e-proctoring software and raises questions

which have yet to be resolved (Ironsi, 2021). In the

Netherlands, complaints have led courts to rule that

e-proctoring software does not violate students’ privacy,

but it also reaffirmed that it must be compliant with data

protection and data privacy laws in the country (Luna-

Bazaldua et al., 2020). The Dutch Personal Data Protection

Act (WBP) requires that students must be able to freely

give their permission for their data to be used, which

means that students must be able to refuse to give this

data without suffering any consequences. In other words,

the WBP requires that an alternative to e-proctored online

examinations, which need access to learners’ data to work

properly, must always be made available for those learners

who refuse to give their permission for their personal data

to be used (and hence cannot take online examinations;

SURF, 2020). Complaints have also been raised at the

University of British Columbia (UBC) in Canada arguing that

online automated proctoring technologies are “ableist and

discriminatory, intrusive, unsafe, inaccessible, and huge

invasion of privacy” with their reliance on facial recognition

technology (Chin, 2020).

E-proctored examinations have also been shown to increase

test takers’ feelings of anxiety and therefore may in fact

affect learners’ academic performance (Ironsi, 2021. During

disruptions to learning, assessments are often given

less importance and at times even cancelled in order to

avoid exacerbating the stressful circumstances (Hodges

et al., 2020). The focus on developing online examination

and proctoring technologies should not put learners at a

disadvantage or expose them to undue stress, especially

when learners have not been previously exposed to these

technologies; decision-makers should be careful to avoid

adding to the anxiety of children and young adults through

the use of unfamiliar technologies (Chin, 2020). Digitised

mock exams may help children transition more easily into a

new online exam modality.

3.2. ADAPTING TO A NEW EXAMINATION MODALITY

3.2.1. TRANSITIONING TO ONLINE EXAMINATIONS

In some cases, the general public may react negatively

to the transition to online examinations. For example,

learners may be worried about how their exam scores will

be affected by the new format, or teachers may express

concerns about adequately equipping learners with digital

literacy skills. Addressing the general public’s opinions and

concerns about online examinations is crucial to mitigating

this risk.

© UNICEF Syria/2021/AlDroubi

Online Examinations in Emergency Contexts

14

Student preparations for online examinations can further be

supported by:

1. Identifying pilot groups who express an interest or

preference to participate in online exams;

2. Giving advance notice of at least one year about the

transition from traditional to online examinations;

3. Holding virtual or in-person workshops about the new

examination format and logistics;

4. Organising a mock examination a few weeks before the

“real” examination;

5. Allowing participants to take the examination multiple

times (at least during the first few years of rolling out

the exam). This can help account for variables that can

negatively affect a student’s score, including emergency

situations, test jitters, etc.

3.2.2. DIGITAL LITERACY

Digital literacy can be defined as the “ability to access,

manage, understand, integrate, communicate, evaluate

and create information safely and appropriately through

digital technologies for employment, decent jobs and

entrepreneurship. It includes competences that are

variously referred to as computer literacy, ICT literacy,

information literacy, and media literacy” (Law et al., 2018).

Possessing digital literacy skills is essential if learners

are to perform well on online examinations. In order for

online examinations to be able to assess learners’ actual

knowledge of the core content that they are being tested

on, learners need to possess the digital literacy skills

that are necessary for them to be able to take online

examinations painlessly. Otherwise, the examination

will effectively be a test of learners’ digital literacy skills,

not their knowledge of content. A study of the results

of learners who took the Partnership for Assessment of

Readiness for College and Careers (PARCC) test in 2015-

2016 found that those learners who took paper-and-pencil

PARCC tests performed 56% better than learners who took

the same exact PARCC test online (Herold, 2016).

Since digital literacy skills are distributed unevenly

across different indicators of disadvantage (such as

income, gender, disability, age, education level, area of

residence — e.g., urban vs. rural —, etc.), one’s previous

exposure to IT will enhance one’s ability to perform better

than others on online examinations, simply because one

possesses digital literacy skills that other learners lack.

This constitutes an unfair advantage. Moving examinations

online without making sure that learners and teachers are

provided with appropriate training in digital literacy skills

will, in all likelihood, increase the disparity in performance

between the most privileged learners and the most

marginalised.

This concern is even more significant in education

emergency contexts where teachers and learners are

more likely to be less acquainted with digital technologies

and where only the most privileged are likely to possess

the necessary digital literacy skills essential to performing

well on online examination. In Syria, more than a decade

of conflict and economic distress resulted in 2.4 million

children dropping out of school, or being forced to access

non-formal education platforms due to lack of access or

affordability to formal education institutions. These children

can often not even afford transportation, stationary or

school uniforms; their opportunities past and future to

develop digital literacy competencies were and are very

limited.

However, it is evidently possible to build digital

competencies and help children and adolescents to

transition from paper-based to digital learning and exam

participation. In fact, Syrian children and adolescents as

well as teachers ask for the opportunity to train and acquire

digital skills. A government or civil society organisation

interested in building digital communication competencies

(writing, drawing, surfing, browsing, checking,

troubleshooting) must be prepared, however, to invest the

time and resources for cultivating and honing digital skill

sets ahead of time, and for different subject topics, and

prior to the day when children are invited to sit for, and

education staff are expected to facilitate proctored online

exams.

In addition to honing digital literacy skills, it would also be

important to explore transforming the current examination

culture that requires children to demonstrate cognitive

capacities through writing, designing and drawing

exercises, to multiple-choice testing modalities that require

a less demanding skill set of digital writing, typewriting and

drawing skills.

© UNICEF Syria/2022/Janji

Online Examinations in Emergency Contexts

15

4. PRE-ASSESSMENT TOOLS

As highlighted in the previous section, the range of

opportunities and risks of online examinations signifies

that the assessment modality may be a good fit for some,

but not all, contexts. This section encompasses two tools

(feasibility criteria and cost analysis) that will support

decision-makers to assess whether online examinations,

and especially online examinations conducted in crisis

contexts, are achievable and affordable.

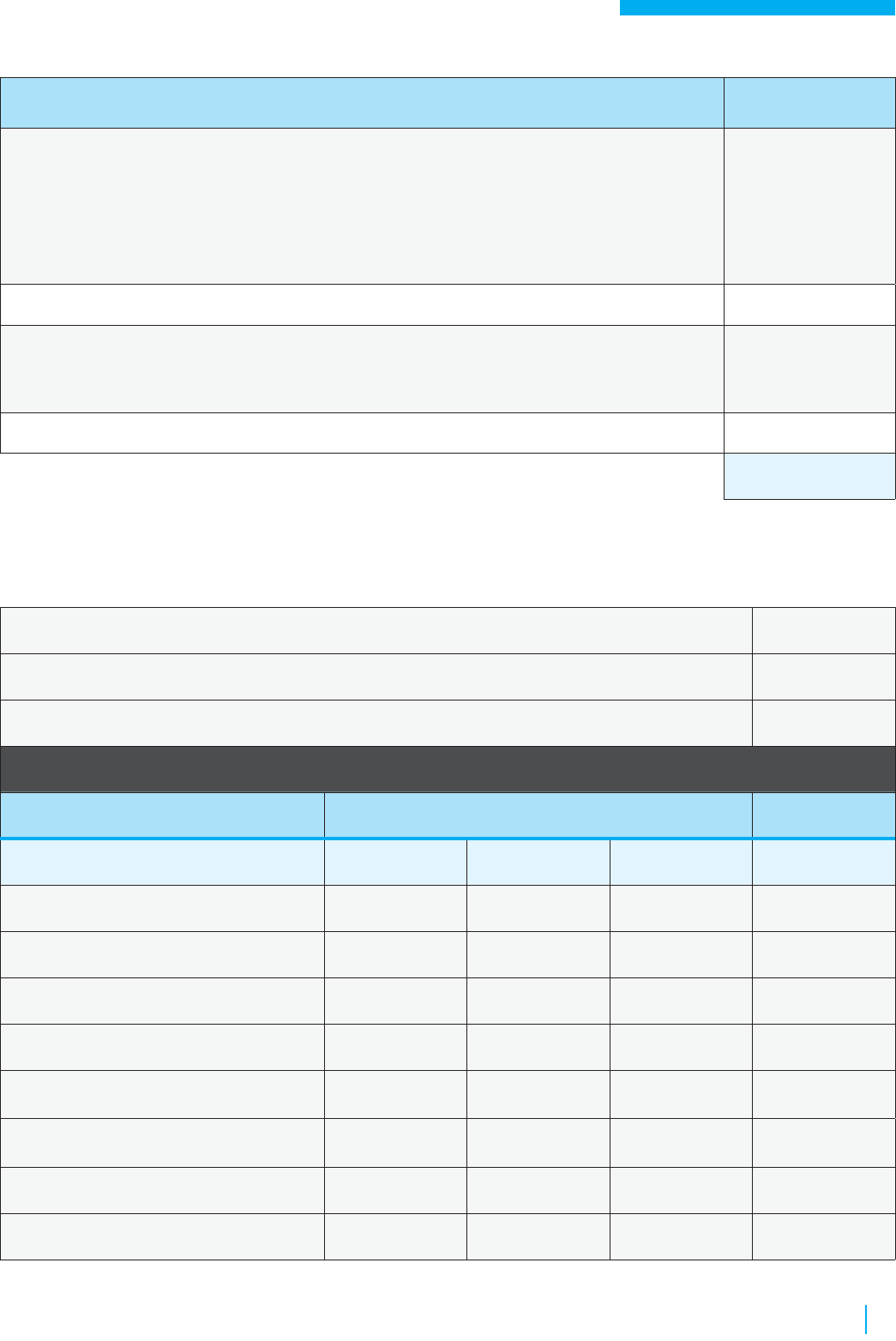

4.1. FEASIBILITY CRITERIA

The table below can be used to determine an overarching

feasibility score (out of 136 points) for lab-based online

examinations. In general, if a score is over 95, then the

context may be a good fit for online examinations.

6

While

this table can serve as a general benchmark for feasibility,

we strongly recommend that any decision-maker consult

with the Ministry of Education and other digital assessment

experts prior to proceeding with implementation. If the

available ICT infrastructure varies significantly across

regions of a country, the feasibility score can be calculated

separately for each region.

The tool is organised across the following categories:

1. Exam location and environment

2. ICT infrastructure and hardware

3. Software

4. Digital literacy skills and training

5. Exam administration

6. Prevention of cheating

7. Equity

6

Note that a score of 95 signifies that roughly 70% of the criteria are met.

© UNICEF Syria/2021/AlDroubi

Online Examinations in Emergency Contexts

16

Category Question Score

1. Exam location and environment Total / 18 :

Exam space

Do the testing locations include:

Л Desks, tables and comfortable chairs

Л Access to bathrooms or latrines

Л Lockers where students can leave their belongings to ensure exam security

To determine your score for this question, add the number of checked boxes (0 — 3).

Exam environment

Will the exam environment:

Л Be quiet and distraction free

Л Be comfortable for students, with proper air circulation and temperature

Л Include live proctoring by trained individuals

To determine your score for this question, add the number of checked boxes (0 — 3).

Exam location part 1

Are there available buildings that can be used for the testing centres?

Л 1 — No, the set-up of tents and / or construction of new buildings are needed for

testing

Л 2 —Yes, buildings are available for testing

Exam location part 2

Will the testing centre be established in a safe location (e.g., a significant distance

from active conflict or natural disasters)?

7

Л 1 — Nov

Л 2 — Yes

Transportation

Participants

Л 1 — Do not have access to any forms of transportation to testing centres

Л 2 — Can access transportation to testing centres, but only for a fee

Л 3 — Can access transportation to testing centres for free

Commute distance

On average, how far will participants need to travel to testing centres?

Л 1 — Over 20 kilometres

Л 2 — Between 4 — 20 kilometres

Л 3 — Less than 4 kilometres

Basic services

Will the testing centre have basic Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WaSH) services

available?

Л 1 — No

Л 2 — Yes

2. ICT infrastructure and hardware Total / 41 :

Electricity

Will testing centres have stable electricity or be powered by alternative energy

sources (e.g., solar)?

Л 1 — No

Л 2 — Sometimes

Л 3 — Yes

Note: If you selected “1” for this question, online examinations may not be feasible

for your context.

7

The ‘Whole of Syria’ Education Sector (2021) defines the severity of the education emergency in a specific area by rating areas from ‘1’ which is the lowest score, to ‘5’ which is the

highest score and describes a catastrophic situation. In Syria, the United Nations prioritizes locations with a severity score of 3 to 5, which are classified as “acute and [in] immediate need of

humanitarian assistance” (Whole of Syria Education Sector, 2021, p. 1). The Severity Scale Framework that forms the basis for the severity scale used in Syria has been developed by the Joint

Intersectoral Analysis Framework Steering Committee (JFIA, 2022). JFIA offers “… a methodologically new approach to analysing the multiple needs of populations in crisis. … Since 2020,

countries preparing humanitarian responses within the Humanitarian Programme Cycle have been using this enhanced approach to inform their country’s ‘Humanitarian Needs Overview’

[HNO].” (p. 1)

Online Examinations in Emergency Contexts

17

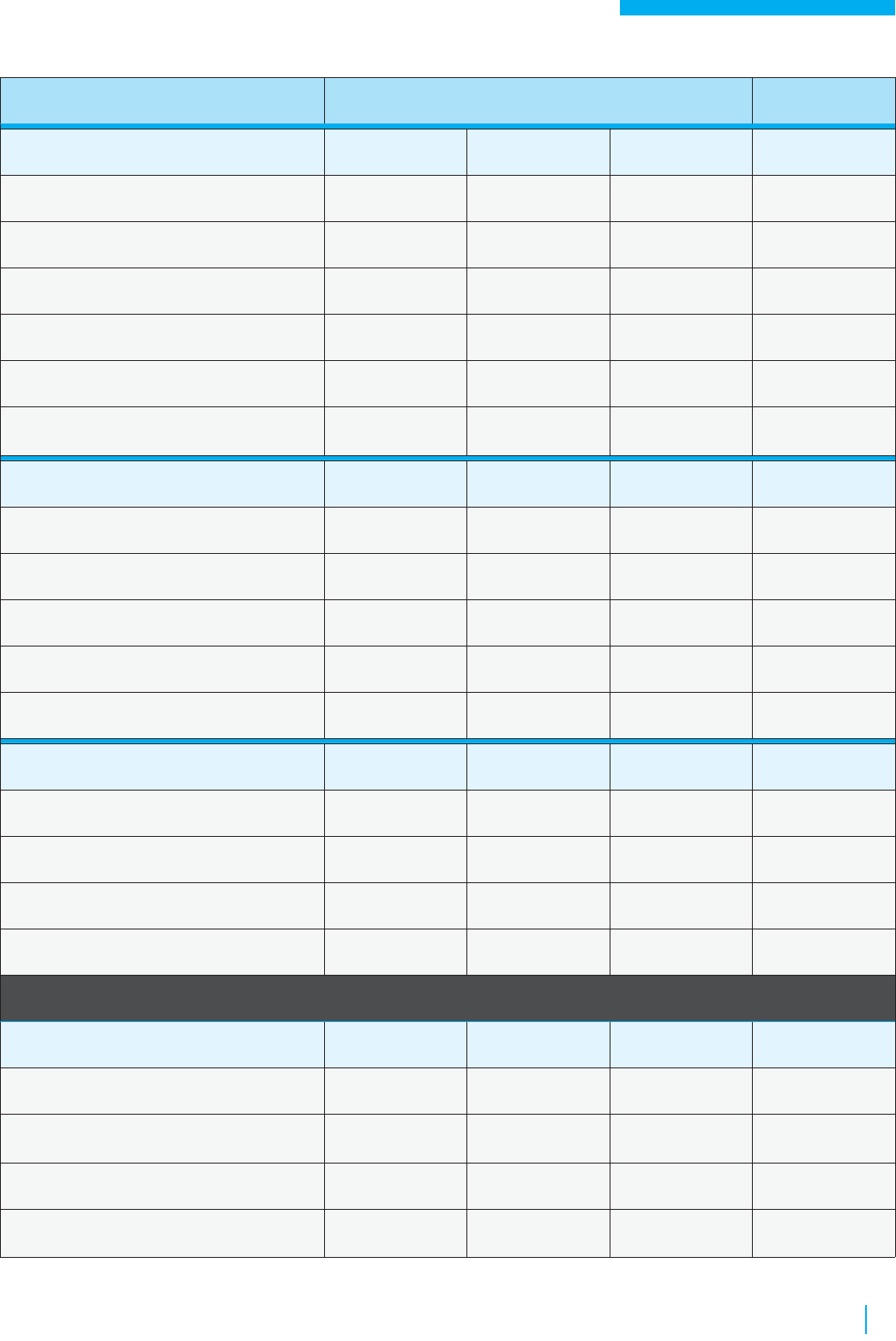

Category Question Score

Internet connectivity

What is the quality of internet connectivity at testing centres?

Л 1 — None to poor (0 — 5 Mbps)

Л 2 — Moderate to good (5 — 25 Mbps)

Л 3 — Very good to excellent (over 25 Mbps)

Note: If you selected “1” for this question, online examinations may not be feasible

for your context.

Internet availability

How available is the internet at testing centres?

Л 1 — Available for a fee or on a personal device

Л 2 — Available through zero costing on the internet connection required for the

testing

Л 3 — Available for free

ICT support

Will testing centres have a technician available to offer support in cases of hardware

and / or software failure?

Л 1 — No

Л 2 — Sometimes

Л 3 — Yes

Centre tools and resources

Will the testing centre include:

Л Pens and paper

Л Computers or tablets for each student

Л Stylus

Л Cameras (webcams)

Л Earphones

Л Calculator

Л Mp3 player / recorder

To determine your score for this question, add the number of checked boxes (0 — 7).

Hardware affordability

What is the per unit cost of the hardware (computers or tablets)?*

• 1 — Over USD 700

• 2 — Between USD 500–700

• 3 — Between USD 200–500

• 4 — Under USD 200

Hardware battery life

What is the battery life of the hardware?

Л 1 — Under 4 hours

Л 2 — Between 4–8 hours

Л 3 — Over 8 hours

Ideally, the hardware should be able to last for an entire school day off-grid in areas

with unreliable electricity.

Hardware storage space

How much storage space is available for each hardware device?

Л 1 — Under 32 GB

Л 2 — Between 32–64 GB

Л 3 — Over 64 GB

Larger amounts of storage are necessary for areas with no or unreliable internet.

Hardware life expectancy

How long is the hardware expected to last before requiring replacement?

Л 1 — Within the year

Л 2 — Within 1 to 3 years

Л 3 — Over 3 years

Online Examinations in Emergency Contexts

18

Category Question Score

Hardware durability

How sensitive will the hardware be towards heat, cold, water and dust and so on?

Л 1 — Sensitive

Л 2 — Somewhat resistant

Л 3 — Resistant

Hardware maintenance

Will there be assigned personnel responsible for hardware maintenance (e.g.,

volunteers, teachers, paid professionals)?

Л 1 — No

Л 2 — Not sure

Л 3 — Yes

Exam tool storage

Will there be a secure location at the testing centre to store the hardware?

Л 1 — No

Л 2 — Not sure

Л 3 — Yes

3. Software Total / 27 :

Origin

Where will the software to be used be developed?

Л 1 — Software development will be outsourced to a foreign corporation

Л 2 — Software development will be outsourced to a national corporation

Л 3 — The government will develop the software in-country

Source

How will the software be sourced?

Л 1 — Paid software

Л 2 — Free, downloadable software

Л 3 — Pre-existing software that is already being used by students, teachers,

and / or MoE staff

Subscription

The software program is available through a:

Л 1 — Subscription basis (yearly, monthly, etc.)

Л 2 — One-time purchase with unlimited usage

Л 3 — N / A; the software is freely available

Connectivity requirements

part 1

Which of the following options is the software able to operate on? If more than one,

select the option with the highest numerical value.

Л 1 — High-speed internet

Л 2 — Mobile networks, including hotspots

Л 3 — Offline

Connectivity requirements

part 2

Does the software require a steady internet connection throughout the duration of

the examination?

Л 1 — Internet connection is required at all times during the exam

Л 2 — Internet connection is required at multiple checkpoints throughout the

exam

Л 3 — Internet connection is only required for download and upload

User capacity

How many test-takers can the software support at one time?

Л 1 — Under 10,000

Л 2 — Between 10,000 to 100,000

Л 3 — Over 100,000

Online Examinations in Emergency Contexts

19

Category Question Score

Technological development

How much additional development will the software require to be suitable for exam

needs?

Л 1 — Requires moderate to extensive development, such as integrating multiple

software

Л 2 — Requires minimal development, such as adjusting existing features of the

existing software

Л 3 — No additional software development required

Available languages

The software program

Л 1 — Is only available in English

Л 2 — Is available in local languages (e.g., Arabic)

Л 3 — Has an automatic translation option

Format

What exam answer options does the software offer?

Л 1 — Multiple choice only

Л 2 — Multiple choice, fill-in-the-blank, and a few other options

Л 3 — Multiple choice, fill-in-the-blank, matching, drawing (using a stylus and

touch screen), open-ended essays, and several other answer options

4. Digital literacy skills and training Total / 15 :

Skills part 1

Do participants possess adequate digital skills to use the hardware (computers or

tablets) and software?

Л 1 — No, participants have not used the hardware and software in schools or at

home

Л 2 — Somewhat, participants have used the hardware, but not the software, in

schools or at home

Л 3 — Yes, participants have used the hardware and software in schools or at

home

Skills part 2

Can participants type?

Л 1 — No, participants have not learned how to type in school or at home

Л 2 — Somewhat, participants have learned how to type in school or at home but

have had limited opportunities to practise

Л 3 — Yes, participants have learned and practised typing in school or at home

Skills part 3

Can participants use a stylus pen?

Л 1 — No, participants have not learned how to use a stylus pen in school or at

home

Л 2 — Somewhat, participants have learned how to use a stylus pen school or at

home but have had limited opportunities to practise

Л 3 — Yes, participants have learned and practised using a stylus pen in school or

at home

Training

What is the anticipated level of training* that will be needed for administrators,

teachers, and learners who will participate in an online examination for the first time?

Л 1 — High: in-person or virtual training sessions by IT support staff or teachers

(accessed synchronously)

Л 2 — Medium: online content or videos (accessed asynchronously)

Л 3 — Low: instructions can be provided right before the examination starts

*Note that training can include topics such as: testing centre rules, day-of logistics,

what to expect for examination content and formats, testing advice and technical

troubleshooting.

Online Examinations in Emergency Contexts

20

Category Question Score

Test prep

How will participants be supported to prepare for the online examinations?

Л Exam duration will be extended (e.g., participants will receive an extra 30

minutes to familiarise themselves with digital exams for each hour they are

given to prepare for paper exams)

Л Guidelines will be shared to help familiarise participants with the exam rules

Л Sample exam formats and questions will be shared

To determine your score for this question, add the number of checked boxes (0 — 3).

5. Exam administration Total / 6 :

Technical difficulties

If there are technical difficulties (due to electricity or connectivity) during the exam:

Л 1 — There is no way to retrieve the data; participants will need to retake the

exam

Л 2 — Participants will be able to continue their exam on paper in the testing

centres

Л 3 — Online progress will be saved and participants can continue at a later date

or after the issue is resolved, or participants can continue to take the exam

offline

Scoring and results

How will online examinations be scored?

Л 1 — Exams will be scored manually by a team of proctors, teachers, etc.

Л 2 — Some exam parts will be scored manually, while others will be scored

automatically using the software

Л 3 — Exams will be scored automatically using the software

6. Prevention of cheating Total / 21 :

ID verification

How will participant identities be verified?

Л 1 — By asking students to enter their contact details into the online examination

Л 2 — By checking national government or student ID approved identification

cards

Л 3 — By checking national government or student ID approved identification

cards, and verifying a match with unique exam ID codes

Seating part 1

Will seating be randomised to prevent cheating?

Л 1 — No

Л 2 — Yes

Seating part 2

Will physical barriers be provided to prevent participants from looking at others’

screens?

Л 1 — No

Л 2 — Yes

Switching screens

Will the participant be able to open other windows on the computer or tablet while

taking the exam?

Л 1 — Yes

Л 2 — No

Proctor capabilities

Will the live or AI proctor be able to:

Л Observe the participants’ screen or environment

Л Check surroundings for prohibited use of notes or textbooks

Л Monitor participants’ eye movements

To determine your score for this question, add the number of checked boxes (0 — 3).

Online Examinations in Emergency Contexts

21

Category Question Score

Proctor code of conduct

What training on code of conduct will proctors be required to take (to ensure

integrity of the proctoring team)?

Л 1 — No training required

Л 2 — Proctors will be required to complete a one-time code of conduct training

Л 3 — Proctors will be required to complete an annual code of conduct training

Disciplinary actions

What disciplinary actions will be enacted for attempts of bribery, fraud and cheating

during the exam?

Л 1 — None

Л 2 — Participants’ score will be disqualified, but they will be allowed to retake

the test

Л 3 — Participants’ score will be disqualified and they will not be able to retake

the test

Reporting

Will students, teachers, proctors and others be able to report incidents of bribery,

fraud and cheating to the Ministry of Education authority?

Л 1 — No

Л 2 — Yes, reports can be shared with a designated official at the MoE

Л 3 — Yes, they can call a hotline to report concerns anonymously

7. Equity Total / 8 :

SEND students

Will participants with special educational needs and / or disabilities (SEND) be

accommodated during online examinations? If yes, how?

Л Audio support will be provided for visually impaired students

Л Braille alphabet keyboards will be provided for visually impaired students

Л Closed captions will be provided for students who are hard of hearing

Л Trained staff will be present at testing centres to support SEND students

To determine your score for this question, add the number of checked boxes (0 — 4).

Opt out

Will participants with special needs or requests be able to opt out of online

examinations and take a paper version instead?

Л 1 — No

Л 2 — Yes

Universal Design for Learning

(UDL)

Have Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles been applied to adapt the

examinations from a paper to online format?

Л 1 — No

Л 2 — Yes

Total Score / 136 :

Online Examinations in Emergency Contexts

22

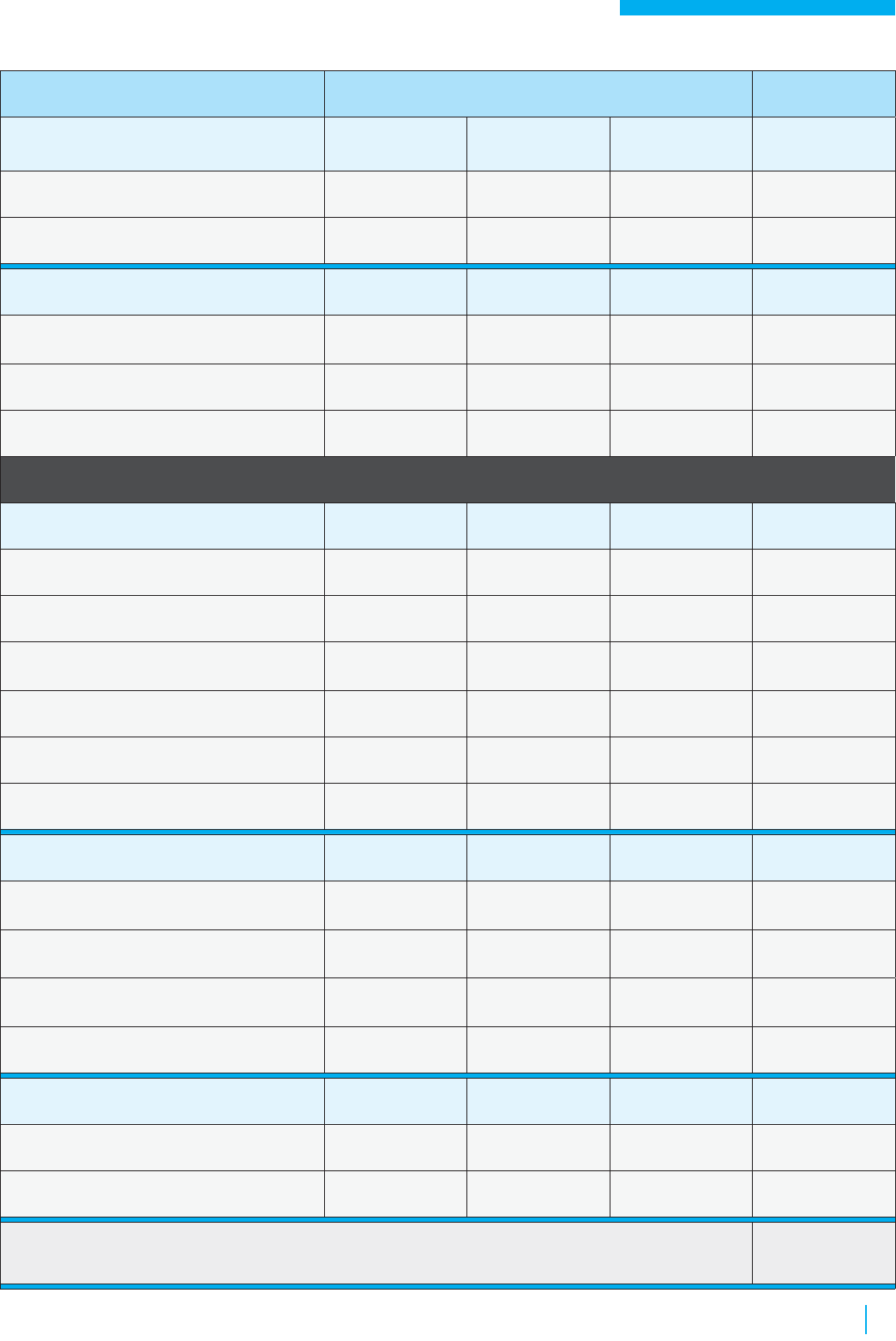

4.2. COST ANALYSIS

A decision-maker can fill out the below table to

calculate the total cost per child of implementing online

examinations. Prior to engaging in this exercise, they should

consider the following:

• Approximately how many children are expected to take

the online examinations? The total cost for each line

item in the table can be divided by the total number of

children to determine the cost per child.

• Who is covering the costs of the online examinations?

For example, will the costs be subsidised by

development partners? Costs can be incurred on

facilities, hardware, software, training, and other

activities which may be needed to implement online

examinations

• Will participants be required to pay a fee to take

the examination? How will equity be ensured, so

that students from low-income families are able to

participate? Will participants be required to pay extra if

they choose to reschedule their exam?

• Are there economies of scale? In other words, will

the cost per child decrease as online examinations are

scaled up nationally?

Item

Cost per child

(please specify currency)

1. Building infrastructure, including but not limited to:

• Desks and tables

• Dividers between desks

• Other furniture

• Additional renovations for testing centres

2. ICT infrastructure and hardware, including but not limited to:

• Internet

• Electricity

• Computers or tablets for each student

• Stylus

• Cameras (webcams)

• Earphones

• Calculator

• Mp3 player / recorder

3. Software fees:

• Online examination platform

• (If applicable) Proctoring AI technologies

• Security system to prevent hacking and ensure data privacy

• Software licensing fee

For consideration: What is the software subscription model (e.g., freemium, per usage, annual fee)? How will this

affect short-term and long-term costs?

4. Salaries of staff, including but not limited to:

• Proctoring team

• IT support team

• Security team for testing centres

• Personalised assistants (for students with special needs)

• Scheduling coordinators (for assigning students to testing centre locations and times)

• Assessment team (if tests need to be scored manually)

• Teachers (for additional examination needs)

• MoE staff

• Subject matter experts to develop and review exam questions

• Instructional designers to ensure that the online examination formatting meets universal design for learning

guidelines

Online Examinations in Emergency Contexts

23

Item

Cost per child

(please specify currency)

5. Training:

• Sessions on running and facilitating online examinations for proctoring and support teams

• Sessions on providing an inclusive environment for all students for proctoring and support teams

• Sessions on how to take the online examination for teachers and students

• Sessions on general digital literacy for teachers and students

• Training materials and resources

6. Learning design, including the annual review of exam questions and formats

7. (If applicable) Transportation of participants to and from the testing centres:

• Drivers

• Vouchers for public transportation