Implementing Care for

Alcohol & Other Drug Use

in Medical Settings

An Extension of SBIRT

SBIRT Change Guide 1.0

February 2018

Introduction ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 1

Overview of Clinical and Organizational Changes Recommended ...................................................................................................3

Clinical Changes .............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 5

Change #1: Screen All Adults At Least Annually ..........................................................................................................................................5

Change #2: Eliciting Symptoms of Alcohol and/or Other Drug Use Disorders ............................................................................. 9

Change #3: Brief Counseling ............................................................................................................................................................................... 13

Change #4: Management of Alcohol or Other Drug Use Disorders ................................................................................................. 16

Change #5: Follow-up with Monitoring ........................................................................................................................................................20

Organizational Changes........................................................................................................................................................................................... 23

Change #6: Leaders Actively Support Improvements ............................................................................................................................ 23

Change #7: Use Quality Improvement Processes .................................................................................................................................... 26

Change #8: Train Primary Care Teams .......................................................................................................................................................... 28

Change #9: Billing and Identifying Revenues for Alcohol and/or Other Drug Care ................................................................ 30

Appendix ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 32

Change #1 Resources: Screen All Adults At Least Annually ............................................................................................................... 32

Change #2 Resources: Eliciting Symptoms ................................................................................................................................................ 34

Change #3 Resources: Brief Counseling ..................................................................................................................................................... 35

Change #4 Resources: Management .............................................................................................................................................................37

Change #5 Resources: Monitoring .................................................................................................................................................................40

Change #8 Resources: Train Primary Care Teams .................................................................................................................................. 42

Change #9 Resources: Billing and Finances .............................................................................................................................................. 43

The Current State of SBIRT in Practice and Research ..........................................................................................................................47

References ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 49

This SBIRT Change Guide was developed by the National Council for Behavioral Health with funding from the Substance

Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) contract no. HHSP233201600258A (February 2018).

SBIRT CHANGE GUIDE 1.0

Katharine Bradley, MD, MPH

Practice Transformation Team Chair

Senior Investigator, Kaiser Permanente Washington

Health Research Institute

Henry Chung, MD

Practice Transformation Team Advisor

Senior Medical Director, Behavioral Health Integration;

Strategy Montefiore Care Management Organization

Professor of Psychiatry, Albert Einstein College of

Medicine

Richard L. Brown, MD, MPH

Professor, University of Wisconsin Department of Family

Medicine and Community Health

Tillman Farley, MD

Chief Medical Ocer, Salud Family Health Centers

Leigh Fischer, MPH

Associate, Abt Associates

Eric Goplerud, PhD

Vice President, National Opinion Research Center;

(NORC) at the University of Chicago Senior Fellow,

NORC at the University of Chicago

Sandeep Kapoor, MD

Director, SBIRT, Division of General Internal Medicine,

Department of Emergency Medicine, Department of

Psychiatry/Behavioral Health, Northwell Health

Hillary Kunins, MD, MPH, MS

Assistant Commissioner, Bureau of Alcohol and Drug

Use, New York City Department of Health and Mental

Hygiene; Clinical Professor, Departments of Medicine,

Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Family and Social

Medicine, Albert Einstein College of Medicine

Richard Saitz, MD, MPH

Chair and Professor of Community Health Sciences

(CHS), Boston University School of Public Health;

Professor of Medicine, Boston University School of

Medicine

Mary Velasquez, PhD

Professor and Director, Health Behavior Research and

Training Institute, The University of Texas at Austin

School of Social Work

Acknowledgements

SBIRT Change Guide Expert Panel

Jake Bowling, MSW

Senior Advisor, Policy and Practice Improvement,

National Council for Behavioral Health

Reed Forman, MSW

Lead Public Health Advisor, SAMHSA

Tom Hill, MSW

Vice President, Addictions and Recovery, National

Council for Behavioral Health

Chuck Ingoglia, MSW

Senior Vice President, Public Policy and Practice

Improvement, National Council for Behavioral Health

Brie Reimann, MPA

Director, SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health

Solutions, National Council for Behavioral Health

Pam Pietruszewski, MA

Integrated Health Consultant, National Council for

Behavioral Health

Nick Szubiak, MSW, LCSW

Director, Clinical Excellence in Addictions, National

Council for Behavioral Health; Integrated Health

Consultant, National Council for Behavioral Health

Mohini Venkatesh, MPH

Vice President, Policy and Practice Improvement,

National Council for Behavioral Health

Aaron Williams, MA

Senior Director, Training and Technical Assistance for

Substance Use, National Council for Behavioral Health

Consultant, Substance Abuse and Mental Health

Services Administration (SAMHSA)/Health Resources

and Service Administration (HRSA) Center for Integrated

Health Solutions

Teresa Halliday, MA

Director, Practice Improvement, National Council for

Behavioral Health

Julia Schreiber, MPH

Project Manager, National Council for Behavioral Health

Sharday Lewis, MPH

Project Manager, National Council for Behavioral Health

Alexandra Meade

Project Coordinator, National Council for Behavioral

Health

Stephanie Swanson

Project Assistant, National Council for Behavioral Health

Megan O’Grady, PhD

Technical Writer; Research Scientist & Associate

Director of Health Services Research, the National

Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse

Acknowledgements, CONT.

Other Contributing Experts Project Management Team

1

T

his change guide is designed to assist primary care clinicians and leaders to integrate care for patients with

unhealthy alcohol and/or other drug use into routine medical care. As behavioral health care is increasingly

integrated into medical settings, especially primary care, the focus is often on depression and anxiety. Care for

alcohol and/or other drugs is often omitted or minimized, likely reflecting: stigma, lack of workforce training/education,

and the traditional separation of care for alcohol and other drugs from traditional health care (e.g., primary care,

emergency care, and behavioral health, etc.). This guide expands on and updates the widely recognized model of

Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT).

1-3

The SBIRT change guide is organized around nine significant changes that most practices need to make to improve

alcohol and/or other drug-related care based a consensus of the authors. Five changes relate to components of clinical

care and four changes address organizational requirements for implementation of the five clinical changes (Figure 1).

Changes #1-3 overlap with the traditional SBIRT model. However, in this guide, “referral to treatment” — the RT in SBIRT

— becomes part of a broader program of management in primary care. This reflects the availability of both evidence-

based medications and ongoing follow-up and counseling that can be provided in primary care (clinical Changes

#4 and #5), independently or in conjunction with specialty addiction treatment.

Each section outlines the rationale for the change, the specific practices recommended, workflow considerations or

components of implementation, and how to measure progress on the recommended change(s) with a recommended

target or “benchmark”. This model, which “extends” the SBIRT model, is intended to support practice improvement and

integration of care for alcohol and/or other drug use into medical settings, as it builds on previous SBIRT guides. Primary

care practices that are already oering SBI for alcohol may also benefit from adding management and monitoring of

alcohol and/or other drug use in primary care. It is not expected that all the changes be implemented at the same time.

Instead, practices can prioritize which changes to implement based on organizational need, resources, and readiness.

Introduction

Figure 1. Overview of the Changes Needed to Address Alcohol and/or Other Drug Use in Primary Care

Clinical Changes Needed Organizational Changes Needed

#6: Leaders actively support

improvements

#7: Use quality improvement

processes

#8: Primary care workforce is trained

in alcohol- and/or other drug-related care

#9: Bill and identify other financial resources

for alcohol- and/or other drug-related care

#1: Screen all adults at least annually

#2: Elicit symptoms

#3: Brief counseling

#4: Manage use

disorders

#5: Follow-up w/

monitoring

2

The Clinical Changes Outlined in Figure 1 are:

(1) Screen all adults at least annually for unhealthy alcohol use

4, 5

and other drug use as part of population-based

prevention and treatment.

(2) Elicit symptoms related to alcohol and/or other drug use from patients with high-positive screens.

(3) Oer brief counseling for unhealthy alcohol

4, 5

and/or other drug use at least annually to all patients with positive

screens.

(4) Manage alcohol and other drug use disorders using shared decision-making

6

to oer medications, counseling,

peer support, referral to specialty addiction treatment programs, and/or home-based services.

(5) Follow-up with monitoring for patients with high-positive screens or symptoms of alcohol and/or other drug

use disorders.

The Organizational Changes Outlined in Figure 1 are:

(6) Leaders actively support improvements in care for patients with unhealthy alcohol and/or other drug use.

(7) Use quality improvement processes to implement each of the five clinical changes.

(8) Train primary care workforce to manage alcohol and other drug use, and/or use disorders, as appropriate.

(9) Bill and identify other financial resources for alcohol and/or other drug related care.

Measuring Successful Change(s). This guide includes recommended metrics for each clinical and organizational change.

They can be used to monitor implementation, inform quality improvement eorts, and quantify progress. Quality

improvement and data system infrastructures are an essential foundation for implementation of improved alcohol- and/

or other drug-related care.

6-8

In most cases, these metrics and benchmarks are based on consensus recommendations

by authors.

Introduction, CONT.

3

Overview: Recommended Clinical & Organizational Changes

Screen all adult patients (≥ 18 years old) for alcohol and other drug use, at least annually, using a structured screening

tool and document the screen scores in the patient’s medical record.

CLINICAL CHANGES

Change #1: Screen All Adults at Least Annually

Use the AUDIT-C for alcohol screening and single-item screening questions for cannabis and other drug use

(AUDIT-C Plus 2).

•

Use a structured questionnaire to assess and document alcohol- and/or other drug-related symptoms if:

Change #2: Eliciting Symptoms

Patients have “high-positive” screening results; and/or

Patients have a clinical evaluation that suggests possible alcohol and/or other drug use disorder.

Use recommended Symptoms Checklists or other validated approaches to elicit alcohol- and drug-related symptoms.

Record questionnaire scores and results in the electronic health record (EHR).

Use patients’ symptoms as a way to engage them in discussions of alcohol- and/or other drug use.

•

•

•

•

•

Oer brief counseling at least once a year for unhealthy alcohol and/or other drug use to all patients with positive screens.

Change #3: Brief Counseling

•

•

•

Patients with unhealthy alcohol use should be oered patient-centered advice about recommended limits and

feedback linking alcohol use to relevant health conditions, based on U.S. Prevention Services Task Force recommendation.

Similar counseling can be oered for cannabis use monthly or more often.

For the subset of patients with high-positive alcohol or other drug screens, experts recommend that patients be

offered ongoing, patient-centered brief counseling, repeated at every visit, in addition to care in Changes #4 and #5.

Manage patients with alcohol- and/or other drug-related symptoms: oer repeated visits for brief counseling and shared

decision-making regarding treatment options and referral, as appropriate.

Change #4: Management

Oer patients shared decision-making about five types of options — medications, one-on-one counseling, peer

support, group-based addiction treatment and patient resources for self-management — including providing referral

for services not provided in primary care, as needed.

•

•

•

Continue ongoing brief counseling as above (i.e. repeated visits with primary care provider, integrated mental health

clinician or specialty addiction treatment, per patient preference).

Adapt care based on results of monitoring, changes in symptoms and patient preferences over time.

Arrange follow-up to monitor alcohol and/or other drug use and symptoms with a structured tool in all patients with high-

positive alcohol and/or other drug screens, or reporting symptoms on the Symptom Checklist.

Change #5: Follow-up with Monitoring

Select a tool for monitoring patients with symptoms.

At a minimum, monitor alcohol and/or other drug use and related symptoms, with repeated brief counseling.

Track alcohol and/or other drug use and symptoms (ideally with a population-based EHR registry).

•

•

•

4

Overview: Recommended Clinical & Organizational Changes

Leaders actively support improvements in alcohol and other drug-related care.

ORGANIZATIONAL CHANGES

Change #6: Leaders Actively Support Improvements

All leaders actively articulate the rationale for improving alcohol- and other drug-related care.

•

•

Use population-based quality improvement processes for each of the five clinical changes.

Change #7: Use Quality Improvement Processes

Assess current gaps in alcohol- and other drug-related care.

Prioritize critical changes to implement (Changes #1 to #5).

Local implementation team (champions) meets regularly; pilot, then implement.

Monitor metrics and set up a quality improvement system, e.g. Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA).

Demonstrate progress on selected change concepts at six months.

•

•

•

•

•

Train primary care teams to address alcohol and other drug use and use disorders in primary care, as appropriate.

Change #8: Train Primary Care Teams

Assess training needs of key sta required for each change.

•

•

Plan training for the entire primary care team (e.g. front desk, sta who conduct patient intakes, primary care clinicians,

behavioral health clinicians), including ongoing assessment of needs and new sta onboarding.

Bill for screening, brief counseling, management, and monitoring, and explore other revenue sources to support the cost

of provision of alcohol- and/or other drug-related services in primary care.

Change #9: Billing and Identifying Other Revenue

If appropriate, use screening and brief intervention, collaborative care or care coordination billing codes.

•

•

Develop a financial model where revenue covers the cost of delivery of alcohol- and other drug-related services.

Leaders select change(s) to implement, identify sta to lead the improvement eort, provide time and resources to

support implementation, set expectations for targets/timing and monitor and provide feedback on performance.

5

Screening identifies patients who are at risk of health or other problems related to their use of alcohol and/or other

drugs, as well as those who have already developed problems.

Unhealthy alcohol and other drug use are common. One in eight adults consumes alcohol at unhealthy levels

and one in 10 people in the U.S. use other drugs.

9

Many patients with alcohol and drug use problems are seen in

primary care

10

; screening and treating these conditions are consistent with patient-centered care.

For unhealthy alcohol use

11

, screening and brief counseling—ongoing on repeated occasions—is one

of the highest prevention priorities recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)

4, 5

based

on cost-effectiveness and burden of preventable disease.

12

For other drug use, screening allows clinicians to open a dialogue with patients about symptoms and other

eects on their health and lives.

Knowing about patients’ alcohol and/or other drug

use is critical to high-quality medical care. Just as

for tobacco use, this information helps clinicians to

properly diagnose, prescribe medications,

13, 14

and

support self-management for chronic diseases (e.g.,

hypertension,

15

diabetes,

15, 16

hepatitis C virus

17, 18

).

Most patients are willing to discuss their alcohol

and drug use and its connection to health

19

and

screening has been associated with improved

patient satisfaction in several studies.

20

Clinical Changes

Change #1: Screen All Adults At Least Annually

For individuals at risk for or diagnosed

with chronic health conditions

(cardiovascular disease, diabetes,

stroke, cancer, among others), alcohol

and other drug use impacts treatment

outcomes via treatment adherence,

medication interactions, and

physiological eects of alcohol and/or

other drug use.

Rationale for Screening

•

•

•

•

•

POPULATIONBASED SCREENING FOR UNHEALTHY ALCOHOL AND OTHER DRUG USE

Screen all adult patients (≥ 18 years old) for alcohol and other drug use, at least annually, using a structured

screening tool and document the screen scores in the patient’s medical record.

Recommendation

Metric

Benchmark

Use the AUDIT-C Plus 2 which combines screens for alcohol (three items), cannabis (one item) and

other drugs (one item), each scored independently.

Proportion of patients with screening results documented.

80%

6

Recommended Screening Tool: The AUDIT-C PLUS 2

Screening tools are available that vary in length, time

needed to administer, and type of drug screened.

3, 21-25

There are a number of factors to consider when

selecting a screening tool for a particular clinical setting

— time needed to administer, validity and reliability, ease

of use, and workforce training are just a few. Screens that

allow patient self-administration are most ecient and

speed workflow. Screening tools that take more than

a few minutes to administer may limit the feasibility of

screening all primary care patients at least annually. This

screen combines validated brief screens for alcohol and

other drugs that are easy for patients to answer, yet useful

for monitoring changes over time. It can be combined

with screening for depression and/or tobacco use.

AUDIT-C Plus 2 Screening Questions

1

* if patient needs further explanation, “for example, for the feeling or experience it caused.”

1

The AUDIT-C has been validated with a past-year timeframe and without any timeframe. The authors recommend a past 3-month timeframe so the

AUDIT-C can be used for monitoring (“Change #5”).

Change #1: Screen All Adults At Least Annually, CONT.

Varying cultural perceptions of alcohol

and other drug use requires clinicians

to implement cultural adaptations to

eectively support diverse populations.

Special attention must be given to

validated screeners, appropriate use

of language/literacy, trust building,

and incorporation of patient and

community healthcare preferences.

To start, consider selecting tools that

are validated in multiple languages,

such as the AUDIT-C.

Click to Access a PDF of the AUDIT-C Plus 2

In the past 3 months...

1. How often did you have

a drink containing alcohol?

2. How many drinks

containing alcohol did you

have on a typical day when

you were drinking?

3. How often did you have

5 or more drinks on one

occasion?

4. How often have you

used marijuana?

5. How often have you

used an illegal drug or a

prescription medication for

non-medical reasons*?

Never

0

Monthly or less

1

2-4 times a month

2-3 times a week 4+ times a week

2 3 4

Never

1 or 2

drinks

0 0 1 2 4

3 or 4

drinks

5 or 6

drinks

7, 8 or 9

drinks

10 or more

drinks

3

Never

0

Less than

monthly

1

Monthly

Weekly

Daily or

almost daily

2 3 4

Never

0

Not monthly

1

Monthly

Weekly Daily or almost

2 3 4

Never

0

Less than

monthly

1

Monthly Weekly

Daily or

almost daily

2 3 4

7

INTERPRETING SCREENING RESULTS

This table shows the recommended screening thresholds and clinical implications for the AUDIT-C Plus 2.

3, 26

See the

Appendix for more information on why these screens are recommended.

Change #1: Screen All Adults At Least Annually, CONT.

Click to Access a PDF of the Interpreting

AUDIT-C Plus 2 Screening Results Table

Table 1.1 Interpreting AUDIT-C Plus 2 Screening Results

Screening Measure

Consider oering positive feedback and

educating patients who drink and use

cannabis about:

•

Recommended drinking limits

27

Screening Results Interpretation Clinical Guidance

AUDIT-C

(0-12 points)

Women: < 3 points

Men: < 4 points

Cannabis question

(0-4 points)

0-1 points

(0 or < monthly)

Other drugs question

(0-4 points)

0 points

(no use)

AUDIT-C

(0-12 points)

Women:

3-6 points

Men:

4-6 points

Cannabis question

(0-4 points)

2-3 points

(monthly or

weekly)

AUDIT-C

(0-12 points)

≥ 7 points

30, 31

Cannabis question

(0-4 points)

4 points

(daily or almost)

Other drugs question

(0-4 points)

1-4 points

(any use)

Negative Screen —

lowest risk (if no

contraindications

for drinking or

cannabis use)

Positive Screen —

drinks or uses

cannabis regularly,

at levels that can

impact health

High Positive Screen —

drinks, uses cannabis

and/or other drugs at

a level that is more

likely to impact health

and therefore needs

further assessment

Low-risk cannabis use.

28

Health risks of alcohol (e.g. cancers,

driving after drinking, pregnancy or

planning)

29

and cannabis use (e.g.

impaired driving, use disorder).

28

•

•

•

Brief counseling per Key Elements in

a patient-centered manner consistent

with motivational interviewing:

Begin conversation, build rapport

Provide feedback on screening

Provide advice or recommendation

Support patient in setting a goal

and/or making a plan

•

•

•

•

•

Elicit symptoms (Change #2)

Ongoing brief counseling (Change #3)

Manage alcohol and/or other drug use

disorders (Change #4)

Follow-up monitoring of use and

symptoms and progress towards goal

(Change #5)

•

•

•

•

8

The recommended target rate (benchmark) for alcohol and/or other drug screening is 80 percent (rather than 100%)

because patients who are in hospice, cognitively impaired, in acute pain, or acutely medically or psychiatrically unstable

may not be appropriate for screening. The screening questions can also be used to monitor patient alcohol or other

drug use over time

34

(see Change #5), so that they are appropriate even for patients who have previously screened

positive or been diagnosed with alcohol or other drug use disorders (who do not need to be “screened,” per se).

Change #1: Screen All Adults At Least Annually, CONT.

Using Metrics to Measure Changes in Screening Rates Over Time

What will you screen for—alcohol only or cannabis and/or other drug use, too? This guide recommends

screening for alcohol, cannabis, and other drugs with five questions; however, you should consider what is most

feasible for your practice.

Will it be combined with a screen for other behavioral health issues? This guide recommends to add the PHQ-2

for depression, if depression screening is not already in place.

32

How often will you screen: annually, at each visit, other? This guide recommends that patients are screened at

least annually.

How will screening questions be administered: computer, paper, sta interview? The most accurate responses

are obtained if patients complete self-report paper or tablets, since reliability of interviews can be low (insensitive

33

).

Results should then be recorded in an EHR.

Will screening questions be built into your EHR? This is recommended, if possible. Alcohol screening should be

entered where other behavioral health screens are entered (e.g., PHQ-2 for depression) so that clinicians can see

responses to individual questions, as well as look at trends for scores over time (for monitoring)—(Change #5). If

so, work with a programmer or EHR vendor early in your implementation process.

How will clinicians be sure to see results of screening at the point of care? Most practices learn that entering

results into the EHR before the clinician sees a patient—if possible—is optimal. This allows for a prompt to the team

for follow-up care (Change #2-4). If clinical sta who do vitals or “room” patients are available, they can ask the

patient to complete a Symptom Checklist to assess for alcohol or drug use disorders, if appropriate (Change #2);

clip a patient handout to the chart or enter a template into the EHR to prompt brief counseling (Change #3); or

alert the clinicians to high-positive screens that needs follow-up.

WORKFLOW CONSIDERATIONS FOR SCREENING

9

Change #2: Eliciting Symptoms of Alcohol and/or Other Drug Use Disorders

A positive alcohol or other drug use screen identifies the spectrum of unhealthy alcohol and drug use from “risky” use

that has not yet caused the patient any problems, to alcohol or other drug use disorders with severe impairment.

30, 31

Eliciting symptoms of alcohol and/or other drug use disorders can help determine where patients are on that spectrum.

Patients’ alcohol and other drug-related symptoms may be powerful motivators of change.

The recommended Symptom Checklists include:

Common problems people have due to alcohol or other drug use,

35

and

The 11 criteria for alcohol and/or other drug use disorders, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual 5

th

edition (DSM-5).

36, 37

The number of symptoms reflects the severity of alcohol or other drug use disorders.

38, 39

As the number of symptoms increases, readiness to change generally increases.

40

Once a patient identifies a symptom, the clinician can elicit more details (e.g., “You indicated you sometimes drink

more than you want, can you tell me more about that?”).

RATIONALE FOR ELICITING SYMPTOMS

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Use a structured questionnaire to assess and document alcohol- and/or other drug-related symptoms if:

Recommendation

Metric

Benchmark

Use the recommended Symptom Checklist with a three-month timeframe or a validated

approach to elicit common symptoms.

Among those with high-positive screen scores, proportion of patients who have documented

assessment of alcohol- and/or other drug-related symptoms in their medical record.

80%

Patients have “high-positive” screening results (e.g., AUDIT-C scores of 7-12 points, daily cannabis

use, any other drug use); and/or

Patients have a clinical evaluation that suggests possible alcohol and/or other drug use disorder.

•

•

Record results of questions and scores in the EHR.

Use patients’ symptoms to engage them in discussions about alcohol and/or other drug use.

•

•

•

10

When Should Symptoms of Alcohol or other Drug Use Disorders Be Elicited?

Symptoms due to alcohol and/or other drug use disorders should be elicited with a standardized tool if patients:

Score “high-positive” on an alcohol or other drug screen (Table 1).

14, 33, 41-53

Are trying to change their alcohol and/or other drug use, but have been unable.

Might benefit from a medication for alcohol or opioid use disorder.

Symptom assessment can also be triggered by other clinical factors such as: vital signs that suggest withdrawal (e.g.,

blood pressure, pulse), lab work suggesting alcohol and/or other drug use disorders

54

(e.g., abnormal liver enzymes),

medications that could be addictive (e.g., opioids, benzodiazepines), psychiatric/medical co-morbidities, and/or severe

social or other life problems due to alcohol and/or other drug use.

Symptom Checklists for Problems Due to Alcohol and Other Drugs

This guide recommends simple Symptom Checklists with 11 items that can be completed quickly and eciently. The

checklists are based on the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for alcohol or other drug use disorders

36, 37

with a past three-

month timeframe so symptoms can be monitored over time. Elicitation of these symptoms can be used to engage

patients in discussions of alcohol- and/or other drug-related problems.

55

The Symptom Checklist can assist with making

a diagnosis.

36, 37

The 11 criteria are used to determine the presence of an alcohol or other drug use disorder.

2-3 symptoms indicate mild alcohol and/or other drug use disorder.

4-5 symptoms indicate moderate alcohol and/or other drug use disorder.

6+ symptoms indicate severe alcohol and/or other drug use disorder.

Medication treatment is an option for moderate to severe for alcohol or opioid use disorders (four or more symptoms).

Change #2: Eliciting Symptoms of Alcohol, Other Drug Use Disorders, CONT.

•

•

•

•

•

•

11

Access a PDF of the Symptom Checklists

Change #2: Eliciting Symptoms of Alcohol, Other Drug Use Disorders, CONT.

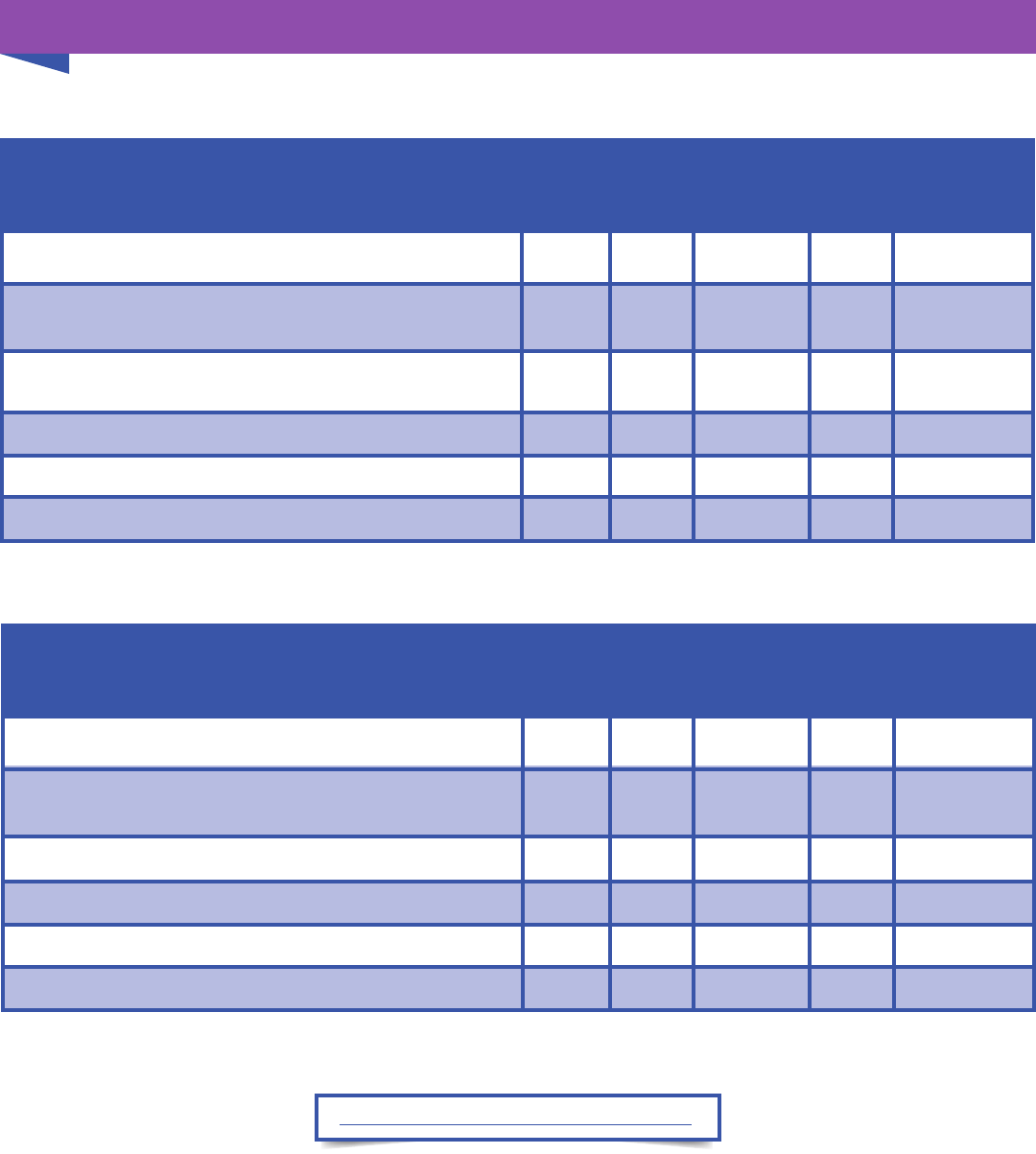

Alcohol Symptom Checklist Other Drugs Symptom Checklist

In the past three months, have you: In the past three months, have you:

Had times when you ended up drinking more, or

for longer than you intended?

More than once, wanted to cut down or stop

drinking, or tried to, but couldn’t?

Spent a lot of time drinking, being sick after

drinking, or getting over the after-eects?

Experienced craving — a strong need, or urge, to

drink?

Found that drinking — or being sick from

drinking — often interfered with taking care of

your home or family, caused job troubles or

school problems?

Continued to drink even though it was causing

trouble with your family or friends?

Given up or cut back on activities that were

important or interesting to you, or gave you

pleasure, in order to drink?

More than once, gotten into situations while or

after drinking that increased your chances of

getting hurt (such as driving, swimming, using

machinery, walking in a dangerous area or

having unsafe sex)?

Continued to drink even though it was making

you feel depressed or anxious or adding to

another health problem, or after having had a

memory blackout?

Had to drink much more than you once did to

get the eect you want, or found that your usual

number of drinks had much less eect than

before?

Found that when the eects of alcohol were

wearing o, you had withdrawal symptoms, such

as trouble sleeping, shakiness, irritability, anxiety,

depression, restlessness, nausea or sweating, or

sensed things that were not there?

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

Y N

Y N

Y N

Y N

Y N

Y N

Y N

Y N

Y N

Y N

Y N

Had times when you ended up using drugs

more, or for longer than you intended?

More than once, wanted to cut down or stop

using drugs, or tried to, but couldn’t?

Spent a lot of time using drugs, being sick after

use, or getting over the after-eects?

Experienced craving — a strong need, or urge, to

use drugs?

Found that using drugs — or being sick from

using drugs — often interfered with taking care

of your home or family, caused job troubles or

school problems?

Continued to use drugs even though it was

causing trouble with your family or friends?

Given up or cut back on activities that were

important or interesting to you, or gave you

pleasure, in order to use drugs?

More than once, gotten into situations while or

after using drugs that increased your chances

of getting hurt (such as driving, swimming,

using machinery, walking in a dangerous area or

having unsafe sex)?

Continued to use drugs even though it was

making you feel depressed or anxious or adding

to another health problem, or after having had a

memory blackout?

Had to use drugs much more than you once did

to get the eect you want, or found that your

usual number of drinks had much less eect

than before?

Found that when the eects of drugs were

wearing o, you had withdrawal symptoms, such

as trouble sleeping, shakiness, irritability, anxiety,

depression, restlessness, nausea or sweating, or

sensed things that were not there?

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

Y N

Y N

Y N

Y N

Y N

Y N

Y N

Y N

Y N

Y N

Y N

12

The recommended target rate (benchmark) for completion of alcohol and/or other drug Symptom Checklists is 80

percent among those with high-positive screen scores. This is not 100 percent because these assessments may not be

appropriate for patients who are in hospice, cognitively impaired, in acute pain, or acutely medically or psychiatrically

unstable, or when other more urgent clinical matters need to be prioritized.

Change #2: Eliciting Symptoms of Alcohol, Other Drug Use Disorders, CONT.

Measuring the Proportion of Eligible Patients Who Complete Symptom Checklists

How soon after a high positive screen should symptoms be elicited? Ideally, symptoms can be assessed the

same day as a high positive screen, but if there are competing priorities that make that impossible, this guide

recommends eliciting symptoms within 3 visits.

Which healthcare clinician or sta will administer the Symptoms Checklist? One approach is to have the person

who rooms patients collect screens and give the Symptom Checklist to patients to fill out before the appointment.

How often will the checklist be administered once a patient has screened as high-positive? At the time of a

high-positive screen and annually thereafter, unless it is being used for monitoring.

Will Symptom Checklists be built into the EHR? If yes, it is recommended that you start working with a programmer

or your EHR vendor very early in your implementation process.

Who will enter results into the EHR so that they can be monitored over time? The person who gives patients

the questionnaires can typically enter results into the EHR at the same time so they are available for all clinicians.

WORKFLOW CONSIDERATIONS FOR ELICITING SYMPTOMS

13

Change #3: Brief Counseling

Brief counseling for unhealthy alcohol use results in decreased drinking among adults with unhealthy alcohol use.

4, 5

Given

the burden of preventable alcohol-related health conditions, and the possible cost-eectiveness of brief counseling,

57

the U.S. Commission on Prevention Priorities ranked brief alcohol counseling one of highest priority preventive services

for U.S. adults.

12

While brief counseling on one or two occasions has not been shown to decrease use of other drugs, one study with

repeated brief counseling suggested it may be eective.

58

Patient-centered discussions about drug use can also help

identify drug use disorders, so that patients can be oered treatment.

The specific elements of brief counseling for patients with unhealthy alcohol and/or other drug use are outlined below

in Table 2, broken into three groups based on the results of screening. However, the frequency and intensity of brief

counseling will depend on the severity of alcohol and/or other drug use, as reflected by the screening score(s) and

drug(s) used, symptoms of alcohol and/or other drug use disorders(s), and clinical knowledge of the patient.

Why Oer Brief Counseling for Unhealthy Alcohol and/or Other Drug Use?

Oer brief counseling at least once a year for unhealthy alcohol and/or other drug use to all patients with

positive screens.

Recommendation

Metric

Benchmark

Patients with unhealthy alcohol use should be oered patient-centered advice about

recommended limits

27

and feedback linking alcohol use to health conditions relevant to the

patient,

56

based on USPSTF recommendation.

4, 5

Among patients with positive screens for alcohol and/or other drug use, the proportion who have

brief counseling documented in their medical records in the last year.

80%

Similar counseling can be oered to patients with at least weekly-to-monthly cannabis use.

28

For the subset of patients with high-positive alcohol or other drug screens, experts recommend

that patients be oered ongoing, patient-centered brief counseling, repeated at every visit, in

addition to care outlined in Changes #4-5.

•

•

•

14

Change #3: Brief Counseling, CONT.

TABLE 2. KEY ELEMENTS OF BRIEF COUNSELING

In this section, expert opinion is outlined on elements of brief counseling that can be oered by primary care

clinicians, or expanded on by behavioral health clinicians who practice in primary care. All elements are

offered using the style and skills from Motivational Interviewing (MI). Components of MI are: open-ended

questions, reflective listening, asking permission before offering advice, eliciting the patient’s perspective after

information is provided, and eliciting statements from the patient for why they want to change. It’s recommended

the clinician elicit the patient’s thoughts. Any goal setting should be arrived at using shared decision-making.

1. Begin the conversation—build rapport

The first task is to build rapport and communicate caring, concern, and non-judgment. Elements included are:

Ask patients if it is okay with them to discuss alcohol and/or other drug use. This can be repeated with each

step below (“Is it okay if I provide some information on results of your screening?”).

Ask open-ended questions about how alcohol and drugs fit into the patient’s life. Explore what types of

alcohol they drink and/or which other drugs they use, with whom, when, where (“Tell me about…”).

2. Provide feedback on results of screening and assessment

The next task is to share with the patient the relevance of alcohol and/or other drug use to his/her health, while

making it clear the clinician respects the patient to make the choices that are right for him/her.

Explore the patient’s experience (“When you completed our form you noted sometimes you are drinking

more than you want. Can you tell me about that?”).

Connect alcohol and/or other drug use to health: specifically link alcohol and/or other drug use to any

symptoms or conditions the patient has or is concerned about, if possible. (“While I hear that drinking is a

critical part of your social life, I’m concerned it may be raising your blood glucose.”)

Elicit patients’ thoughts (“What do you make of this information?”).

3. Provide advice or a clinical recommendation

Recommendations depend on the patient, drug(s) used, severity of use and symptoms, and resources. Management

of patients with high-positive screens, symptoms, or alcohol and/or other drug use disorders are addressed in Change

#4, but brief counseling based on MI and decision-making provides the foundation of ongoing management.

For alcohol, all patients should be advised about recommended drinking limits that decrease the risk of

developing or re-developing adverse consequences due to drinking (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse

and Alcoholism [NIAAA] provides guidelines on recommended limits).

For less than daily cannabis use, explore reasons for use (medical, recreational) and ways to minimize health risks.

For patients with alcohol and/or other drug use disorders, stopping use improves outcomes.

Give patients the opportunity to express desires, reasons, commitment, and ability to change.

4. Support the patient in setting a goal and making a plan

Explore options that the patient feels are realistic and obtainable.

Arrange follow-up to monitor and adapt management.

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

15

Using Metrics to Measure Changes in Counseling Rates Over Time

If screening is recorded with an EHR registry, measurement of documented brief counseling can also use the EHR

registry, either through a field that notes this was done, via billing codes, or non-billable z-codes. If paper charts are

used, then some number of chart reviews for patients who had positive screens can be performed to assess “crude” brief

counseling percentages.

WORKFLOW CONSIDERATIONS FOR BRIEF COUNSELING

Which healthcare clinicians or sta will oer ongoing brief counseling? Often this will be provided by the primary

care clinician but sometimes, when a patient has a high-positive screen, alcohol or other drug use disorder, or other

mental health conditions, a warm hand-o to an integrated behavioral health clinician (if available) is optimal.

How often will brief counseling be provided? This will depend on the severity of symptoms (if any) and the resources

of the medical setting. At a minimum, patients with alcohol and/or other drug use disorders should be scheduled for

follow-up and monitoring quarterly, even if they are not interested in treatment.

When does brief counseling fit in during the visit? Oering brief counseling can often be linked to the chief complaint

(e.g., hypertension, insomnia, fracture) or can be added at the end of the appointment after asking permission to discuss

the patient’s screening. If the counseling is oered by an integrated behavioral health clinician, it can be after the

appointment with the primary care clinician.

How will the brief counseling session be documented? If counseling is part of an appointment billed with an E&M

code, the counseling can be documented with a non-billable z-code. When a warm hand-o to an integrated behavioral

health clinician occurs, brief counseling can be documented with an SBI code if >15 minutes and not part of another

appointment.

Change #3: Brief Counseling, CONT.

16

Rationale for Managing Alcohol and/or Other Drug Use in Primary Care

Alcohol and/or other drug use disorders are common conditions appropriate for long-term primary care.

64

Management in primary care oers patients more immediate care within a familiar system.

65

Specialty addiction treatment is often not available.

Many patients don’t feel like their problems require

“treatment,” so they don’t accept a referral,

66, 67

but

they can succeed in patient-centered primary care.

Even when patients do accept referral to specialty

treatment, drop-out rates may be high, and unless

patients are treated with medications, treatment is

usually short-term (12 weeks), and many patients still

need chronic management in primary care.

A number of studies have demonstrated how

alcohol and/or opioid use disorders can be

managed in primary care.

1, 68-75

Change #4: Management of Alcohol or Other Drug Use Disorders

•

•

•

•

•

•

Options for Managing Patients in

Primary Care

Medication

Counseling

Referral to

group-based

addiction

treatments

Peer support

Primary

care support

for self-

management

Manage patients with alcohol- and/or other drug-related symptoms: oer repeated visits for brief counseling

and shared decision-making regarding treatment options and referral, as appropriate.

Recommendation

Metric

Benchmark

Oer patients shared decision-making about five types of options and refer as needed if services are

not available in primary care.

o Medications such as naltrexone and acamprosate for alcohol disorders and buprenorphine

naltrexone, or methadone for opioid use disorders in primary or specialty care.

59

o One-on-one behavioral treatments for alcohol and/or other drug use disorders by a

behavioral health clinician (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy, motivational enhancement

therapy),

1, 60, 61

which can be integrated into primary care.

64

o Peer support groups (e.g., Alcoholics, Narcotics Anonymous (AA, NA,

62

, SMART Recovery

63

).

o Group-based treatment as provided by most specialty addiction treatment programs.

o No treatment at this time, but possible self-management, with continued primary care

support with monitoring and motivational interviewing.

Among patients with alcohol and/or other drug use symptoms on a structured tool, the proportion

who have a follow-up visit that addresses alcohol and/or other drug use within 90 days.

80%

• Continue ongoing brief counseling. Provide ongoing alcohol- and/or other drug-related care

(i.e., repeated visits)—within primary care, mental health, or specialty addiction treatment

settings, per patient preference—to support self-management and change.

• Adapt care based on results of monitoring and changes in symptoms and patient preferences.

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

17

ELEMENTS OF PRIMARY CARE MANAGEMENT

Treatment of alcohol and/or other drug use disorders can include medications and counseling, encouraging

peer support, referral to specialty addiction treatment (in the medical setting or in the community) and support

for patient self-management. Utilizing the collaborative care consulting methodology, either virtually or on-site,

primary care physicians may benefit from the expertise of addictions specialists. Sites may choose to embed this

practice with regular supervision or through contracting with a colleague for ad hoc consultation on complex cases.

Medications for Alcohol and Drug Use Disorders

Medications for alcohol use disorders (AUDs) improve response to behavioral treatment,

59, 76

and naltrexone can

decrease heavy drinking as well.

70

The FDA has approved three medications for alcohol use disorders: naltrexone, acamprosate, and disulfiram.

These medications can be prescribed in primary care with medication management focused on assessing

use and symptoms, recommending abstinence in a patient-centered manner, medication adherence, and

encouraging participation in peer support.

70

Follow-up can be every 1-2 weeks for 2 months and then monthly

when patients are stable.

Care management by a nurse, recommending abstinence and naltrexone, is associated with improved

engagement in alcohol-related care and decreased drinking compared to “referral to treatment” in primary care

patients not seeking addiction treatment.

70

Two medications for opioid use disorders (OUDs)

71, 77

—methadone or buprenorphine—improve patient outcomes for

OUDs, and are far superior compared to counseling and other behavioral treatments alone.

78, 79

Opioid use disorders

due to heroin and prescription opioids are responsive to these treatments.

80

Methadone and buprenorphine both lead

to decreased mortality and morbidity for patients on these medications long-term (i.e. maintenance therapy). Evidence

for the eectiveness of injectable, extended release naltrexone is emerging.

81

Buprenorphine can be prescribed in primary care by primary care providers who have a buprenorphine waiver

from the DEA (requiring an 8-hour course that can be taken online).

71, 81, 82

Free virtual mentorship for treating

OUDs with buprenorphine is also available.

82

Extended release naltrexone can also be prescribed in primary care with monthly injections.

OUDs can only be treated with methadone in special Outpatient Treatment Programs approved for methadone

maintenance.

Care management for OUDs is associated with high rates of retention, and a central part of primary care

management.

Medication to prevent opioid overdose if patients are still using opioids or at risk of relapse.

Naloxone (Narcan—not to be confused with naltrexone) can decrease death due to overdose.

Change #4: Management of Alcohol or Other Drug Use Disorders, CONT.

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

18

ONEONONE COUNSELING

Motivational Interviewing, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and other one-on-one counseling approaches are

eective for alcohol and/or other drug use disorders.

60, 61

A primary care trial suggests a six session CBT/MI brief therapy

is eective when provided to patients not seeking treatment by an integrated behavioral health clinician in primary

care.

1

The FDA recently approved a proven digital counseling program for alcohol and/or other drug use disorders.

83

Encourage Participation in Peer Support

84, 85

Peer support groups can help patients who want to make changes. AA is associated with improved outcomes, in part due

to new social networks. Alternatives to AA and other twelve-step programs, like Self-Management and Recovery Training

(SMART) recovery

63

provide an alternative for those who are uncomfortable with the spiritual component of AA.

Referral to Specialty Addiction Treatment

Referral to specialty treatment options. A small percentage of patients may need and be open to referral to

specialty alcohol and/or other drug treatment. It is important to improve engagement in treatment by having

protocols and procedures for linking patients to internal (within the same organization) or external treatment

resources. In order to optimize the chances of a successful specialty treatment referral, it is crucial to develop a

standard and consistent workflow.

Specialty addiction treatment in the medical setting. When internal specialty addition treatment is available, the ease

of linking to treatment may have significant advantages, such as: capability for warm hand-os; documentation

within the same medical record and collaboration with primary care. Even with these seeming advantages, a detailed

workflow is highly recommended with defined roles in order to achieve high engagement rates.

External addiction treatment programs. When internal resources are not available, forging strong partnerships

with external addiction specialists is essential to improving access to care and improving patient satisfaction.

Successful referrals to external services require addiction specialists and primary care clinicians to communicate,

collaborate, and evaluate the eectiveness of the relationship. Identification of available, accessible treatment

resources is key and developing functional partnerships with external specialty addiction treatment clinicians in

the community will improve patient care.

Confidentiality of Care in Specialty Addiction Treatment Programs. Confidentiality must be considered when

making referrals for specialty addiction treatment. Sharing of treatment information is strongly recommended and

documented patient consent to share addiction treatment program information is legally required under 42CFR

Part II. For more information, see SAMHSA’s A Guide to Substance Abuse Services for Primary Care Clinicians..

Monitoring in primary care after treatment. If a patient is referred to specialty addition treatment, the primary

care team should follow-up to determine if the patient engaged in treatment, and to monitor response to, and

for relapse after, treatment.

Resources regarding specialty addiction treatment.

Selecting from a spectrum of treatment intensities. See Appendix or an overview of levels of care for

alcohol and other drug use disorders.

Successful referral practices for alcohol and/or other drug use disorders. See Appendix for more information.

See Management Resources in the Appendix for more information on treatment options.

Change #4: Management of Alcohol or Other Drug Use Disorders, CONT.

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

19

SHARED DECISIONMAKING

In shared decision-making, clinicians work collaboratively with patients when there are multiple options for care—

for example, considering treatment options for alcohol or opioid use disorder (e.g., medications, counseling, group-

based specialty addiction treatment, peer support, or self-management). Shared decision-making is particularly

important when the patient has to execute the treatment—as in behavior change—as well as when choices patients

might make would dier from those clinicians might recommend.

86

When oering shared decision-making,

clinicians help patients understand they have choices (including no treatment), provide information comparing

options, elicit patient values and preferences, and support them in making a decision that fits them best.

70, 87

In

shared decision-making, the patient is the expert.

88

Shared decision-making is essential to patient-centered care

for alcohol and/or other drug use disorders.

35

There is a progression of steps when using shared decision-making

that help patients make informed decisions.

89

Clinicians inform patients on choices: medications, one-on-one counseling, group-based treatments, peer

support, and no treatment (but continued primary care support), depending on the patients’ alcohol and/or

other drug use disorder and the availability of treatments in the community.

Patients’ preferences, values, and priorities are considered. These include, but are not limited to: privacy,

logistics, cost, and preferred treatment approaches.

Patients should be supported in making a decision and accessing treatment.

Provision of decision aids (print, video, and/or online resources) can assist in helping the patient and clinician

better understand and weigh options together. A decision aid tool for opioid use disorder treatment is

available through SAMHSA.

Change #4: Management of Alcohol or Other Drug Use Disorders, CONT.

•

•

•

•

Patient Self-Management with Repeated Brief Counseling and Monitoring in Primary Care

Patients with alcohol and/or other drug use disorders who are not interested in medications for AUD or OUD, counseling,

specialty treatment, or peer support, should nonetheless be oered repeated brief counseling with MI and shared

decision-making in primary care. Several studies support repeated brief counseling for high-risk drinking and/or alcohol

and/or other drug use disorders.

58, 68-70

Treatment of comorbid mental health and/or medical conditions may also be used to build rapport and engagement in

treatment, or can lead to changes in alcohol and/or other drug use.

Patient or

provider

conveys that

treatment

choices exist

Patient is

informed

about

treatment

options

Support

patient in

exploring own

values and

preferences

Support

patient in

making a

decision on

their own

20

Rationale

Follow-up with systematic symptom monitoring is critical for knowing:

Whether patients’ symptoms are increasing or decreasing.

Whether or not patients treated with medications or counseling in primary care are benefiting and if they are

achieving their goals.

When treatment needs to be changed or augmented if there is not adequate improvement.

Change #5: Follow-Up With Monitoring

•

•

•

Arrange follow-up to monitor alcohol and/or other drug use and symptoms with a structured tool in all patients

with high-positive alcohol and/or other drug screens, or reporting symptoms on the Symptom Checklist.

Recommendation

Metric

Benchmark

Select a tool for monitoring patients with symptoms.

At a minimum, monitor frequency of use with the AUDIT-C Plus 2 every three months.

90

Ideally, also monitor symptoms of use (questions #2-5 of the Short Alcohol Monitor and/or

Short Drug Use Monitor).

Ideally, monitor whether patient is achieving their own goals regarding alcohol and/or other

drug use (Questions #1 of the Short Alcohol Monitor and/or Short Drug Use Monitor). If

patients are not responding to treatment, reassess with MI and shared decision-making and

adapt or change treatment(s).

Among patients with high-positive screening scores or alcohol- or other drug-related symptoms,

proportion who have a follow-up contact within three months of high-positive screening score or

report of alcohol- or other drug-related symptoms.

80%

•

•

Repeated visits for monitoring should include: repeated brief counseling with MI and shared decision-

making, tracking alcohol and/or other drug use and symptoms, and patient self-assessment of alcohol

and/or other drug use.

Develop tracking protocols (e.g., EHR registry) for ensuring population-based follow-up based on

clinical severity, at least every three months.

21

WHAT ARE THE IMPORTANT COMPONENTS OF FOLLOWUP WITH MONITORING?

1. Monitoring: systematic measurement over time to guide care

Quality improvement research over the past 20 years has shown that whether one is treating hypertension, diabetes,

or depression, measurement-based care improves outcomes. Unfortunately, unlike depression (for which there is

widespread use of the PHQ-9 to monitor symptoms and response to treatment), there is no standard practical approach

to systematic monitoring of alcohol and/or other drug-use and symptoms in primary care. However, several systems

have successfully used alcohol and/or other drug use screening questions for monitoring,

91

and validated discriminating

questions for alcohol and/or other drug use disorders have been identified by the National Institute of Health (NIH)

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS).

92, 93

Important dimensions of alcohol and/or other drug use to monitor likely include:

The extent to which alcohol or other drug use is interfering with patients’ goals (family, relationships, health).

Severity of consequences due to alcohol and/or other drug use.

Severity of symptoms of loss of control over alcohol and/or other drug use or craving.

Level of current alcohol and/or other drug use.

Experience with depression management in primary care indicates that brief instruments should be used for monitoring.

Thus, this guide recommends use of the AUDIT-C Plus 2 screening questions, at a minimum (with a past three-month

timeframe). Additionally, this guide recommends five-item tools to monitor symptoms and functioning — one for

alcohol and one for other drugs, as outlined in the following table. These ten items can be administered along with the

AUDIT-C Plus 2. Questions #2-5 are adapted from the PROMIS.

94,92, 93

*Response choices for all: Never, Rarely, Sometimes, Often, Almost Always

Alternative options for monitoring are the full AUDIT (alcohol),

22

CUDIT

95

(cannabis), and DUDIT

96

(other drugs). For

these tools, the monitoring timeframe should be adjusted from one year to three months. The ASSIST

97, 9 8

can also be

used. Another alternative is to monitor with the Alcohol or Drug Use Symptom Checklists. These tools may have merit,

but they are longer and more specific to individual drugs. Nevertheless, these may be reasonable options in settings

where these tools are already being used systematically.

•

•

•

•

Change #5: Follow-Up With Monitoring, CONT.

Short Alcohol Monitor Short Drug Monitor

How often in the past 2 weeks... How often in the past 2 weeks...

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Were you bothered by how your drinking impacted your

health, relationships, goals or life?

Did you have trouble controlling your drinking, drink too

much or spend too much time drinking?

Was it dicult to get the thought of drinking out of your mind?

Did you disappoint yourself or others due to drinking?

Have you had trouble getting things done due to drinking?

Were you bothered by how your drug use impacted your

health, relationships, goals or life?

Did you spend a lot of time using drugs?

Were drugs the only thing you could think about?

Did you disappoint yourself or others due to drug use?

Did you feel your drug use was out of control?

22

WORKFLOW CONSIDERATIONS FOR FOLLOWUP WITH MONITORING

Who will schedule follow-up? Will it be in person or by phone? This will depend on patients’ other medical

conditions and treatments, how soon they are willing to return or have a phone appointment, and co-pays.

How often? This guide recommends monitoring at least quarterly.

Who will do the monitoring? Generally, monitoring fits into the workflow just as screening does.

How will the system know if a patient does not make a follow-up appointment or cancels? EHR registries

can assist a behavioral health clinician in primary care or a nurse managing a population of patients with alcohol

and/or other drug use disorders.

What communication strategies will be used between internal and/or external behavioral health clinicians?

An EHR registry as above can also assist in monitoring patients who are receiving outside treatment.

2. Repeated brief counseling as part of monitoring

Given the considerable impact of alcohol and/or other drug use disorders on patients’ health and well-being, it is

appropriate and essential to incorporate routine follow-up for all patients with symptoms of alcohol and/or other

drug use disorders into standard care. Research shows that brief multi-contact counseling, as described previously,

along with shared decision-making, is eective. Comorbid medical conditions (e.g., anxiety, depression, HCV) can be

managed concurrently.

3. Medication management, integrated with monitoring, as appropriate

For patients on medications, close follow-up is important to assess for side-eects and monitor adherence. Care

management for medications for alcohol use disorders often includes encouraging peer support, while monitoring for

medications for opioid use disorders often includes urine drug screens.

4. Monitoring after referral—both internal to the health care organization and external

Some patients with alcohol and/or other drug use disorders will benefit from specialty addiction treatment or

other mental health services for comorbid conditions. When patients choose specialty treatment, clinicians must

be prepared to support patients connecting to treatment resources and to follow-up after the patient engages in

specialty treatment.

Change #5: Follow-Up With Monitoring, CONT.

23

Rationale

Clinical Changes #1-5 are complex changes to the way patient care is provided for all primary care team members.

Leaders, at all levels of a health system, need to actively support clinical changes to ensure successful and sustained

implementation.

What is active leadership support?

Active support for improvements in alcohol and/or other drug use in primary care includes:

Leaders select which change to implement. Leaders can start by assessing gaps in alcohol- and/or other drug-

related care or can select the first change(s) to implement based on knowledge of their clinic(s). Often, clinics

start with screening (Change #1), eliciting alcohol and/or other drug related symptoms with a standard tool

(Change #2), and brief counseling (Change # 3) – “SBI” of “SBIRT”. While 15-25 percent of patients will have

unhealthy use of alcohol or other drugs, only 1-2 percent of patients typically screen high-positive or have

alcohol and/or other drug use disorders. However, addressing management of alcohol and/or other drug use

disorders (Change #4)—and sta training needs regarding management—can improve clinician comfort when

those patients are identified.

Organizational Changes

Change #6: Leaders Actively Support Improvements

Leaders actively support improvements in alcohol and other drug-related care.

Recommendation

Metric

Benchmark

Leaders at all levels of the organization actively articulate the rationale for integrating improved

alcohol- and/or other drug-related prevention and management as part of primary care.

Leaders need to:

Select the clinical change(s) to implement (#1-5).

Identify champions to lead the alcohol and/or other drug use quality improvement eort in

each clinic (implementation team).

Provide time and resources to support implementation.

Set expectations for targets and timing and provide monitoring and feedback on performance.

Leadership selects an implementation team and prioritizes one or more clinical Changes (#1-5) to

be implemented.

Implementation meets benchmark(s) for the clinical change selected (#1-5) within six months.

•

•

•

•

24

Other Considerations

Identifying sta to lead quality improvement in the clinics: Identify an interdisciplinary team in each clinic to be responsible

for implementation of a selected change. This should include at a minimum: a primary care physician/clinician, support

sta (e.g., nurse, medical assistant, or health tech), and an integrated behavioral health clinician, if one practices in the clinic.

Other suggested champions include: front desk sta, administrative leadership or sta, float sta, pharmacists, a quality

improvement expert, billing representative, peer navigators, other key clinic personnel, and a clinical EHR programmer for

assistance with EHR development and adjustments.

Committing resources: Provide an initial financial investment of time for local implementation team meetings and piloting,

time for clinicians to partner with IT/programmers to develop EHR decision support, time for work force development,

commitment to stang with behavioral health clinicians in primary care (e.g., social work, nurses), support for data analytics

for timely reports on metrics, and time to identify and partner with community resources.

Monitoring and feedback: Attend/lead regular quality improvement meetings to review metrics and problem-solve using

PDCA, and to hold direct reports accountable for measurement and meeting selected targets.

Leadership provides ongoing support for the value and the importance of the changes: Leaders tell stories about the

central value of the work and frontline experience of success.

Augmenting the primary care team: Consider hiring a dedicated care manager or care coordinator, preferably with a

behavioral health background to help manage patients with alcohol and/or other drug use disorders in addition to other

behavioral health needs. Care coordinators, typically nurses or social workers, provide services like case management,

medication management, monitoring of patient health status, and counseling and support for patient self-management

of their alcohol and/or other drug use. Peer navigators can also help connect patients to needed resources.

Change #6: Leaders Actively Support Improvements, CONT.

ROADMAP FOR CLINIC LEADERSHIP SUPPORT

Set implementation in motion. If large health system, leader(s) select pilot clinics and key gap(s) in quality via assessment

of the current state. Leaders select initial change (#1-5) to implement, tools, and targets.

Select and empower interdisciplinary local implementation team. Explain the gap and expectation for change to the

local implementation team. Leaders arrange for workforce development for local implementation team.

Leaders kick-o initial pilot with primary care clinician champion(s) and medical assistant or dyad partner(s). Pilot

includes iterative huddles or meetings to problem-solve challenges (Plan-Do-Check-Act [PDCA]).

Oversee iterative improvement. Local implementation team meetings occur weekly/biweekly (1 hour). Leaders review

progress monthly at quality improvement (PDCA) meetings.

Support the importance of the work. Communicate expectations to leaders at all levels of the organization regarding

importance of the quality improvement eort. Leaders at all levels continually spread positive stories.

Consider hiring a dedicated care manager/coordinator or expanding the role of health coaches or care managers to

include alcohol and/or other drug use.

25

Establishing and maintaining partnerships with specialty addiction treatment services: For internal partnerships, leaders

create the platform for internal planning discussions and sponsor the infrastructure needed to support the collaboration. If

the partnership is external, leaders broker the arrangement and maintain a relationship with the partner leadership team,

to develop seamless communication pathways and follow-up. This is especially critical given that 42 CFR Part II requires

specific written documentation of consent for sharing information from a specialty addiction treatment program.

Troubleshooting challenges and celebrating small successes: Leaders problem-solve barriers and highlight the

incremental successes that lead to achieving organizational change.

Change #6: Leaders Actively Support Improvements, CONT.

26

Rationale

Implementing improved alcohol and/or other drug care is a major quality improvement (QI) initiative, not dissimilar

from other primary care QI projects focused on the triple aim. In June 2017, the National Committee for Quality

Assurance added the Unhealthy Alcohol Use Screening and Follow-Up measure to the Healthcare Eectiveness Data and

Information Set (HEDIS) 2018 for health plan reporting. This measure assesses the percentage of health plan members

eighteen years and older who were screened for unhealthy alcohol use and, if screened positive, received appropriate

follow-up care within two months. As health systems move toward EHRs, building structured fields and approaches

for standardized screening tools and follow-up care will encourage screening and allow easier monitoring of quality of

care. Clinician education on evidence-based models, as well as aligned incentives to oer screening and follow-up, will

help encourage their administration.

To achieve the goal of sustainable alcohol- and/or other drug-related care, attention must be given to: 1) planning

for implementation, 2) piloting to make rapid cycle changes to refine workflow before changes are disseminated to

others in a clinical practice, 3) assessing the pilot impact and outcomes, and 4) creating organizational buy-in to spread

changes in workflow to the entire clinical practice.

Change #7: Use Quality Improvement Processes

Use population-based quality improvement processes for each of the five clinical changes.

Recommendation

Metric

Benchmark

Assess current gaps in alcohol and/or other drug-related care.

Prioritize clinical Changes(s) #1-5 to implement.

Local implementation team members (i.e., champions) meet regularly: pilot, then implement.

Monitoring metrics by establishing a quality improvement system (e.g., PDCA).

Demonstrate progress on selected change concepts at six months.

Prioritized changes are in rapid cycle pilot testing within 2 months and implemented at six months

and sustained at 12 months

100%

•

•

•

•

•

27

Change #7: Use Quality Improvement Processes, CONT.

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

ROADMAP FOR QUALITY IMPROVEMENT

1. Planning for implementation