DATA COLLECTION SURVEY

ON

UNIVERSAL HEALTH COVERAGE

IN

THE PHILIPPINES

DECEMBER 2016

JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA)

GLOBAL LINK MANAGEMENT, INC.

HM

JR

16-077

Exchange Rate

US$ 1 = ¥ 104.76

1 Philippine Peso = ¥ 2.16

(JICA Rate in November 2016)

i

LIST OF ACRONYMS/ABBREVIATIONS

Acronyms/

Abbreviations

Standard Nomenclature

ADB

Asian Development Bank

ANC

Antenatal Care

ANC01

Antenatal Care Package

AOP

Annual Operational Plan

ARMM

Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao

BEmONC

Basic Emergency Maternal Obstetrics and Newborn Care

BHS

Barangay Health Station

BHW

Barangay Health Worker

BMC

Bicol Medical Center

BRTTH

Bicol Regional Training and Teaching Hospital

CAR

Cordillera Administrative Region

CCT

Conditional Cash Transfer

CEmONC

Comprehensive Emergency Maternal Obstetrics and Newborn Care

CHT

Community Health Team

CHTF

Common Health Trust Fund

CS

Camarines Sur

DBM

Department of Budget and Management

DHS

Demographic and Health Survey

DMO

Development Management Officer

DOF

Department of Finance

DOH

Department of Health

DSWD

Department of Social Welfare and Development

EU

European Union

EVRMC

Eastern Visayas Regional Medical Center

FBD

Facility-based Delivery

FGD

Focus Group Discussions

FHSIS

Field Health Service Information System

FIES

Family Income and Expenditure Survey

GDP

Gross Domestic Product

GIDA

Geographically Isolated and Disadvantaged Areas

GNI

Gross National Income

GSIS

Government Service Insurance System

HMO

Health Maintenance Organization

ILHZ

Inter-Local Health Zone

IRA

Internal Revenue Allotment

IT

Information and Technology

I3QUIP

The Impact of Incentives and Information on Quality and Utilization in

Primary Care

JICA

Japan International Cooperation Agency

KII

Key Informant Interview

KOICA

Korea International Cooperation Agency

KP

Kalusugan Pangkalahatan

LGC

Local Government Code 1991

IMR

Infant Mortality Rate

LGU

Local Government Unit

LHSD

Local Health Support Division

LIPH

Local Investment Plan for Health

MCH

Maternal and Child Health

ii

Acronyms/

Abbreviations

Standard Nomenclature

MCP

Maternal Care Package

MDGs

Millennium Development Goals

MDR

Medical Data Record

MMR

Maternal Mortality Ratio

MNCHN/FP

Maternal, Neonatal, Child Health and Nutrition/ Family Planning

MNDR

Maternal and Newborn Death Review

MSW

Medical Social Worker

NBB

No Balance Billing

NCP

Newborn Care Package

NDHS

National Demographic and Health Survey

NEDA

National Economic and Development Authority

NGO

Non-Governmental Organization

NHIP

National Health Insurance Program

NHTS-PR

National Household Targeting System for Poverty Reduction

NSD

Normal Spontaneous Delivery

OBGYN

Obstetrics and Gynecology

ODA

Official Development Assistance

PCB1

Primary Care Benefit 1

PCPT

Per Capita Poverty Threshold

PhilHealth

The Philippine Health Insurance Corporation

PHRD

Policy and Human Resources Development

PI

Poverty Incidence

PMRF

PhilHealth Member Registration Form

PMT

Proxy Means Test

PNC

Postnatal Care

POC

Point of Care

PSPI

Population Services Philipinas, Inc.

PRISM2

The Private Sector Mobilization for Family Health Project – Phase 2

PSA

Philippine Statistics Authority

RHMPP

Rural Health Midwives Replacement Program

RHU

Rural Health Unit

SAEs

Small Area Estimates

SBA

Skilled Birth Attendant

SDGs

Sustainable Development Goals

SDN

Service Delivery Network

SSS

Social Security System

SSV

Supportive Supervision

TBA

Traditional Birth Attendant

TCL

Target/ Client List

TseKaP

Tamag Serbisyo para sa Kalusugan ng Pamilya

UHC

Universal Health Coverage

UNFPA

United Nations Population Fund

UNICEF

United Nations Children’s Fund

USAID

United States Agency for International Development

WHO

World Health Organization

ZFF

Zuelling Family Foundation

iii

DATA COLLECTION SURVEY

ON UNIVERSAL HEALTH COVERAGE

IN THE PHILIPPINES

TABLE OF CONTENTS

List of Acronyms/Abbreviations ................................................................................................ i

Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................... iii

Attachments ................................................................................................................................v

List of Figures, Tables and Boxes ..............................................................................................v

Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................1

Chapter 1 Overview of the Survey ..........................................................................................2

1-1 Background ...................................................................................................................2

1-2 Objectives .....................................................................................................................3

1-3 Scope of the Survey ......................................................................................................3

1-4 Survey Areas .................................................................................................................4

1-5 Methodology .................................................................................................................5

(1) Literature review ...................................................................................................5

(2) Field data collection ..............................................................................................5

1-6 Survey Team .................................................................................................................8

1-7 Survey Schedule ............................................................................................................8

Chapter 2 Socio-Economic Situation in the Philippines ...................................................... 10

2-1 Geography, Ethnicity and Religion ............................................................................. 10

2-2 Population Statistics and Future Projections ............................................................... 10

2-3 Poverty and Economic Disparity ................................................................................. 13

2-4 Industrial Structure and Labor Market ........................................................................ 15

Chapter 3 Overview of the Health Sector ............................................................................ 16

3-1 Health System with a Focus on Maternal and Child Health ........................................ 16

(1) Health Governance ............................................................................................. 16

(2) Health Policies .................................................................................................... 17

(3) Health Financing ................................................................................................. 20

(4) Health Facilities and MCH Service Delivery ...................................................... 31

(5) Health-related Information .................................................................................. 33

3-2 Maternal and Child Health Conditions ........................................................................ 35

(1) Maternal conditions ............................................................................................ 35

(2) Child mortality .................................................................................................... 36

(3) Teenage Pregnancy ............................................................................................. 36

iv

3-3 Assistance of Development Partners ........................................................................... 37

(1) Development Partners in the Philippine Health Sector ....................................... 37

(2) Trends of the Assistance by Development Partners in the Philippine Health

Sector .................................................................................................................. 38

(3) Details of Assistance by Development Partners .................................................. 39

Chapter 4 National Health Insurance Program (NHIP) – Overview and Utilization ............ 51

4-1 Current Framework of NHIP ....................................................................................... 51

4-2 PhilHealth ................................................................................................................... 51

4-3 Goals for the Philippine Health Agenda ...................................................................... 52

4-4 Membership Category ................................................................................................. 52

4-5 Enrollment Procedures ................................................................................................ 54

4-6 Premium Contributions ............................................................................................... 55

4-7 Payment Mechanisms .................................................................................................. 56

4-8 Benefit Packages ......................................................................................................... 57

(1) Inpatient Benefit Package ................................................................................... 57

(2) Outpatient Benefit Package ................................................................................. 58

(3) Z Benefit Package ............................................................................................... 59

(4) MDG related package ......................................................................................... 60

4-9 Claim Procedures ........................................................................................................ 62

4-10 Accreditation Processes............................................................................................... 63

(1) Health Facilities .................................................................................................. 63

(2) Professionals ....................................................................................................... 64

4-11 Funding for PhilHealth ................................................................................................ 64

4-12 Cross Subsidy among PhilHealth members ................................................................. 65

4-13 Enrollment and Utilization .......................................................................................... 66

(1) Population Coverage ........................................................................................... 66

(2) NHIP Utilization ................................................................................................. 67

4-14 Supporting Indigents ................................................................................................... 67

(1) Facilitating Enrollments for Indigent Members .................................................. 67

(2) No Balance Billing Policy................................................................................... 68

(3) Point-of-Care Enrollment Program ..................................................................... 69

(4) Conditional Cash Transfer .................................................................................. 70

Chapter 5 Maternal and Child Health Services in Bicol and Eastern Visayas Regions ... 73

5-1 Bicol Region (Region V) ............................................................................................. 73

(1) Regional Profile .................................................................................................. 73

(2) Overview of Study Sites ..................................................................................... 75

v

(3) Study Findings .................................................................................................... 76

5-2 Eastern Visayas (Region VIII) ..................................................................................... 87

(1) Regional Profile .................................................................................................. 87

(2) Field Study .......................................................................................................... 91

(3) Study Findings .................................................................................................... 93

Chapter 6 Good Practices and Challenges of JICA Projects ............................................ 107

6-1 Surveyed Projects ...................................................................................................... 107

6-2 Interview Sites........................................................................................................... 107

6-3 Survey Findings ........................................................................................................ 108

(1) Good Practices .................................................................................................. 108

(2) Challenges ........................................................................................................ 111

Chapter 7 Recommendations for JICA’s Future Assistance ............................................ 113

7-1 Points to be Considered ............................................................................................. 113

7-2 Recommendations for JICA’s future activities .......................................................... 113

(1) Access to Quality Essential Health-Care Services ............................................ 113

(2) Financial Risk Protection .................................................................................. 116

7-3 Project Sites .............................................................................................................. 118

7-4 Enhancement of Project Up-scaling Mechanism ....................................................... 118

ReferenceS 120

ATTACHMENTS

1. The Schedule of the First Field Survey (Manila) ....................................................... A-1

2. The Schedule of the Second Field Survey (Bicol) ...................................................... A-2

3. The Schedule of the Second Field Survey (CAR & Eastern Visayas) ........................ A-3

4. The Schedule of the Third Field Survey (Manila) ...................................................... A-5

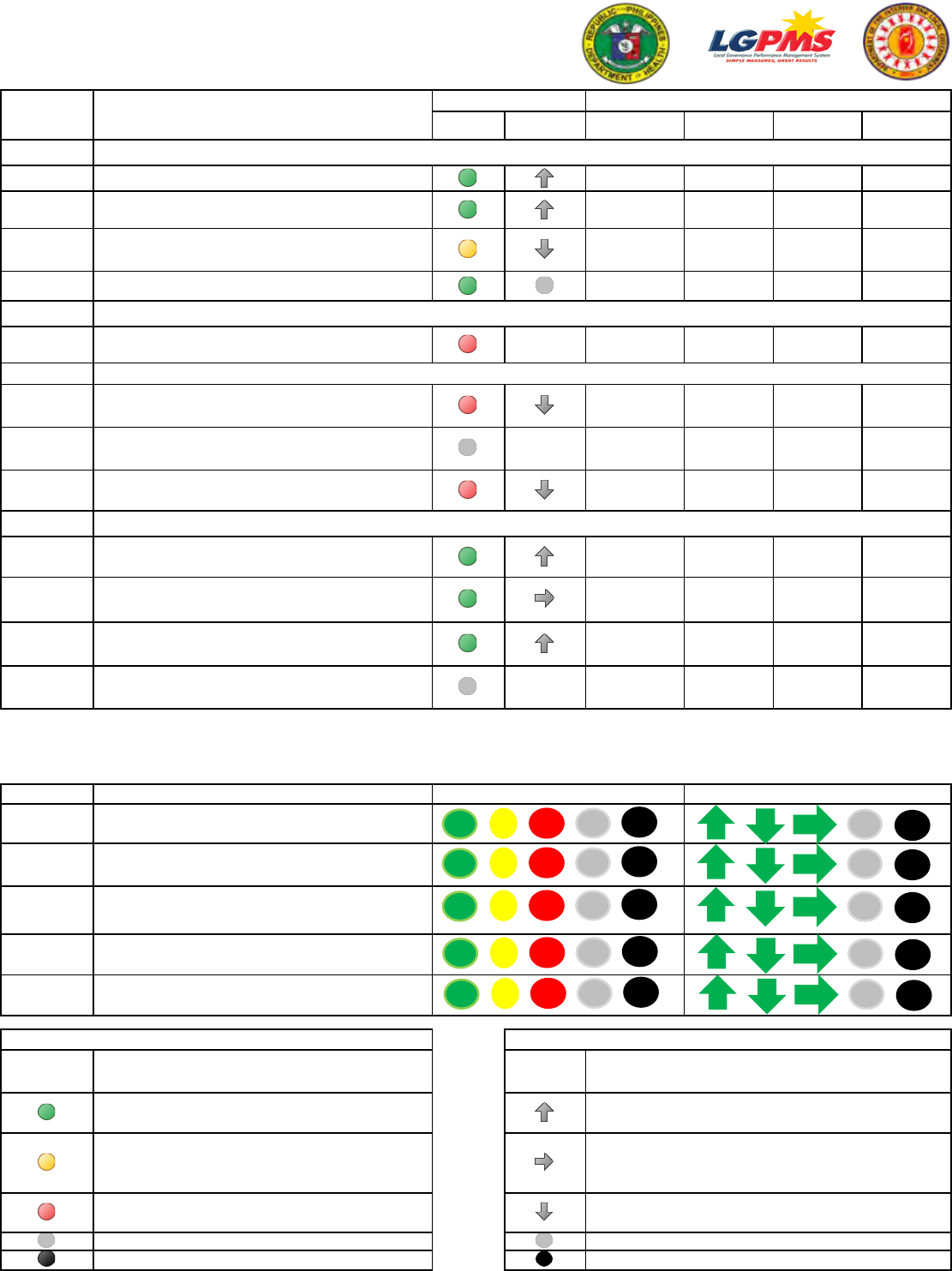

5. The LGU Health Score Cards .................................................................................... A-6

6. Family Assessment Form ........................................................................................... A-8

LIST OF FIGURES, TABLES AND BOXES

CHAPTER 1

FIGURE 1- 1 MAP PF THE PHILIPPINES ......................................................................................... 4

FIGURE 1- 2 THE WORK FLOW OF THE DATA COLLECTION SURVEY ON UHC IN THE PHILIPPINES9

TABLE 1- 1 SCOPE OF THE SURVEY .............................................................................................. 4

vi

TABLE 1- 2 SELECTION CRITERIA OF THE FIELD DATA COLLECTION TAGET AREAS ...................... 5

TABLE 1- 3 LIST OF DATA TO BE REVIEWED DURING THE SURVEY................................................ 6

TABLE 1- 4 LIST OF KEY INFORMANTS DURING THE FIELD DATA COLLECTION ............................ 8

TABLE 1- 5 SURVEY TEAM MEMBERS ........................................................................................... 8

CHAPTER 2

FIGURE 2- 1 POPULATION PYRAMID OF THE PHILIPPINES, 2015 (IN THOUSANDS) ....................... 11

FIGURE 2- 2 NATIONAL AND REGIONAL POPULATION IN THE PHILIPPINES (2000-2015) ............ 11

FIGURE 2- 3 TRENDS OF POVERTY HEADCOUNT RATIO AT NATIONAL POVERTY LINES (% OF

POPULATION) IN ASEAN COUNTRIES IN 1997-2014 ............................................................. 14

FIGURE 2- 4 TRENDS OF POVERTY GAP AT NATIONAL POVERTY LINES (%) IN ASEAN COUNTRIES

IN 1997-2012 ...................................................................................................................... 14

FIGURE 2- 5 TRENDS OF GINI INDEX (WORLD BANK ESTIMATE) IN SOUTHEAST ASIAN

COUNTRIES IN 1981-2012 .................................................................................................... 15

CHAPTER 3

FIGURE 3- 1 HEALTH GOVERNANCE STRUCTURE IN THE PHILIPPINES ........................................ 16

FIGURE 3- 2 HEALTH EXPENDITURES, TOTAL (% OF GDP) ........................................................ 21

FIGURE 3- 3 OUT-OF-POCKET HEALTH EXPENDITURE (% OF TOTAL HEALTH EXPENDITURE ON

HEALTH) ............................................................................................................................. 21

FIGURE 3- 4 2014 HEALTH EXPENDITURES BY FACTORS OF HEALTH CARE PROVISIONS .............. 22

FIGURE 3- 5 2014 HEALTH EXPENDITURES BY HEALTH SERVICES AND HEALTH FINANCING

SCHEMES (IN MILLION PESOS) .............................................................................................. 22

FIGURE 3- 6 HEALTH EXPENDITURES BY INCOME QUINTILE GROUP: THE PHILIPPINES,

2012-2014 (IN MILLION PESOS) ........................................................................................... 23

FIGURE 3- 7 HEALTH EXPENDITURES BY INCOME QUINTILE GROUP AND HEALTH FINANCING

SCHEMES: THE PHILIPPINES, 2012-2014 (IN MILLION PESOS) ............................................... 23

FIGURE 3- 8 HEALTH EXPENDITURES BY DISEASE GROUPS AND HEALTH FINANCING SCHEMES:

THE PHILIPPINES, 2014 (IN MILLION PESOS) ......................................................................... 24

FIGURE 3- 9 HEALTH EXPENDITURES BY SPECIFIC DISEASE GROUPS AND HEALTH FINANCIAL

SCHEMES: THE PHILIPPINES, 2014 (IN MILLION PESOS) ........................................................ 25

FIGURE 3- 10 BUDGET AND BREAKDOWNS OF HEALTH BUDGET, 2011-2015 (IN PESOS) ............ 26

FIGURE 3- 11 REVENUE SOURCES AND FLOWS WITHIN THE PUBLIC HEALTH SYSTEM IN THE

PHILIPPINES ........................................................................................................................ 31

FIGURE 3- 12 TRENDS OF TOTAL FERTILITY RATE AND THE TEENAGE FERTILITY OUT OF TOTAL

FERTILITY RATE FROM 1973 TO 2013 IN THE PHILIPPINES .................................................... 37

vii

FIGURE 3- 13 DONOR CONTRIBUTIONS IN PHILIPPINE HEALTH SECTOR AS OF THE END OF

DECEMBER 2015 .................................................................................................................. 38

FIGURE 3- 14 AREAS OF ASSISTANCES BY DONORS AS OF THE END OF DECEMBER 2015 .............. 38

FIGURE 3- 15 DOH BUDGETS AND AMOUNT OF DONOR ASSISTANCES (1998-2016).................. 39

TABLE 3- 1 20 HIGH POVERTY SITES ......................................................................................... 20

TABLE 3- 2 HEALTH FINANCING IN THE PHILIPPINES ................................................................. 20

TABLE 3- 3 DISTRIBUTION OF SIN TAX INCREMENTAL REVENUE IN FY 2016 DOH BUDGET

PROPOSAL ........................................................................................................................... 27

TABLE 3- 4 IRA DISTRIBUTION VS. ESTIMATED SHARE OF DEVOLVED FUNCTIONS..................... 28

TABLE 3- 5 LOCAL TAXES .......................................................................................................... 29

TABLE 3- 6 2003-2007 CASE STUDIES OF VISAYA AND LUZON: LGU ANNUAL INCOME

BREAKDOWNS...................................................................................................................... 29

TABLE 3- 7 PUBLIC HEALTH FACILITIES ...................................................................................... 31

TABLE 3- 8 BASIS FUNCTIONS OF HEALTH FACILITIES................................................................ 32

TABLE 3- 9 MAJOR MCH SERVICES BY VARIOUS HEALTH FACILITIES ........................................... 32

TABLE 3- 10 TARGET REGIONS AND PROVINCES FOR THE USAID ASSISTED MNCHN/FP

PROGRAMS .......................................................................................................................... 42

BOX 3- 1 PHILIPPINES HEALTH AGENDA 2016-2022 ................................................................. 18

BOX 3- 2 THE 10-POINT SOCIOECONOMIC AGENDA OF PRESIDENT DUTERTE ........................... 19

CHAPTER 4

FIGURE 4- 1 ORGANIZATIONAL CHART OF PHILHEALTH ............................................................ 51

FIGURE 4- 2 REIMBURSEMENT FLOWS UNDER CASE RATE FOR PNEUMONIA II (HIGH RISK) ........ 57

FIGURE 4- 3 PREMIUM CONTRIBUTION TO PHILHEALTH BY MEMBERSHIP CATEGORIES (IN PESOS)

........................................................................................................................................... 65

TABLE 4- 1 PHILHEALTH MEMBERSHIP CATEGORY.................................................................... 53

TABLE 4- 2 ENROLLMENT PROCEDURES BY MEMBERSHIP CATEGORY ........................................ 54

TABLE 4- 3 PREMIUM PAYMENT PROCEDURES ........................................................................... 55

TABLE 4- 4 CASE RATE PAYMENT INTRODUCED IN 2011 – CASES AND RATES (IN PESOS) ............ 56

TABLE 4- 5 PRIMARY CARE SERVICE OFFERED UNDER TSEKAP PROGRAM ................................. 58

TABLE 4- 6 OUTPATIENT BENEFIT PACKAGES OFFERED BY PHILHEALTH (OTHER THAN TSEKAP)

........................................................................................................................................... 59

TABLE 4- 7 Z BENEFIT PACKAGE: YEAR OF INTRODUCTION AND CASE RATES (IN PESOS) ........... 59

viii

TABLE 4- 8 CONTRACTED HOSPITALS FOR ELECTIVE SURGERY FOR CORONARY ARTERY BYPASS

GRAPH ................................................................................................................................ 60

TABLE 4- 9 MATERNITY CARE PACKAGE (IN PESOS) ................................................................... 61

TABLE 4- 10 NCB PACKAGE (IN PESOS) ..................................................................................... 62

TABLE 4- 11 OTHER MDG RELATED PACKAGES (IN PESOS) ....................................................... 62

TABLE 4- 12 INSTITUTIONAL PROVIDERS WITH PHILHEALTH ACCREDITATIONS ........................ 64

TABLE 4- 13 NUMBER OF ACCREDITED OUTPATIENT CLINICS, NUMBER AND PERCENTAGE OF

CITIES AND MUNICIPALITIES WITH ACCREDITED OUTPATIENT CLINICS ............................... 64

TABLE 4- 14 PREMIUM CONTRIBUTIONS AND BENEFIT CLAIMS FOR 2015 BY NHIP MEMBERS ... 65

TABLE 4- 15 NUMBER OF COVERED MEMBERS AND COVERAGE RATIO FROM 2010 TO 2015 ....... 66

TABLE 4- 16 NHIP UTILIZATION FROM 2012 TO 2015NHIP ..................................................... 67

TABLE 4- 17 PATIENT CATEGORIES BASED ON THE ABILITY TO PAY AND RESPECTIVE PAYMENT

AMOUNTS ........................................................................................................................... 70

CHAPTER 5

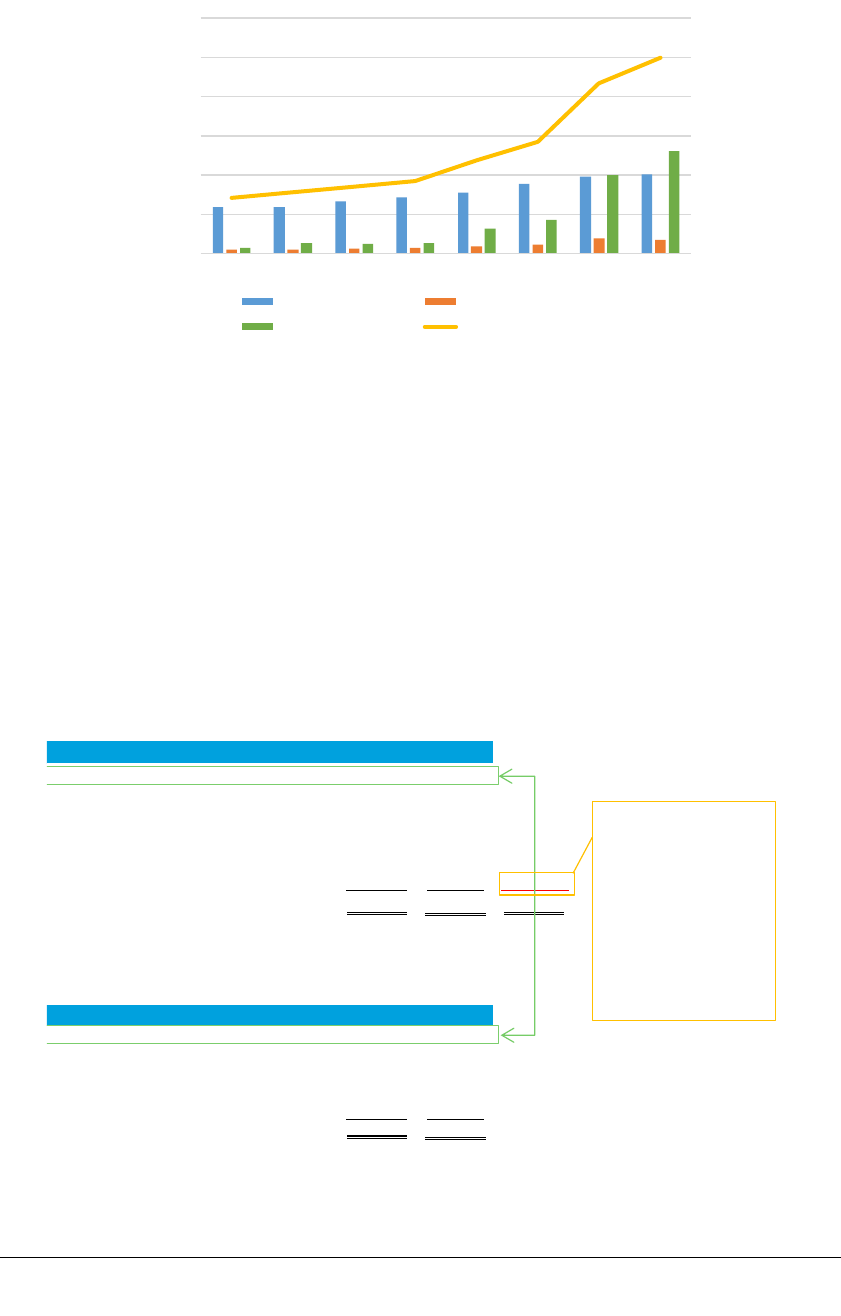

FIGURE 5- 1 TREND OF MATERNAL DEATHS AND MMR IN BICOL ............................................... 74

FIGURE 5- 2 RURAL HEALTH UNIT IN CAMARINES SUR ............................................................. 77

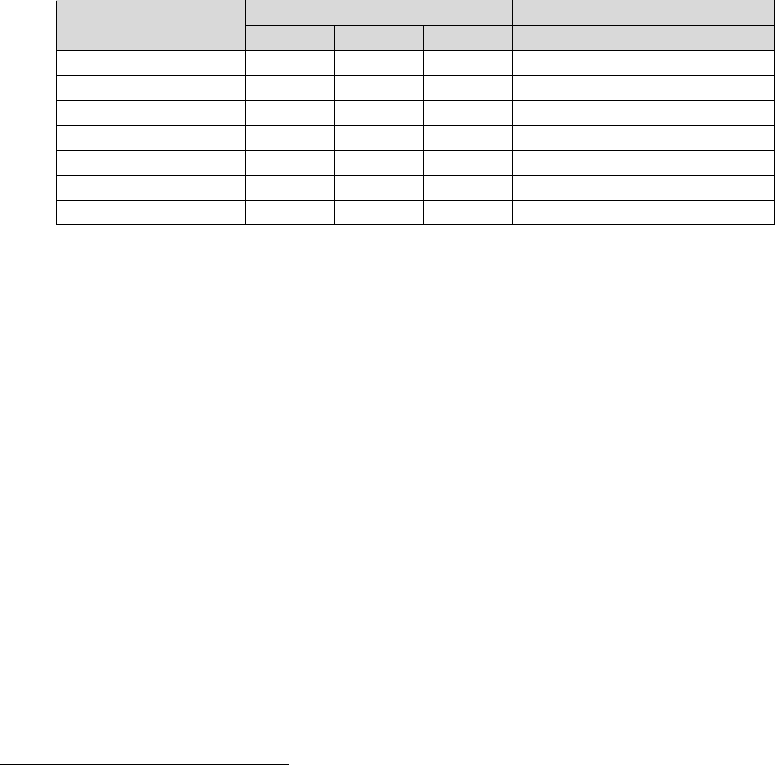

FIGURE 5- 3 BRTTH ................................................................................................................. 79

FIGURE 5- 4 PHILHEALTH BICOL REGIONAL OFFICE ................................................................. 80

FIGURE 5- 5 BARANGAY HEALTH STATION IN CAMARINES SUR ................................................... 81

FIGURE 5- 6 GROUP DISCUSSION WITH PREGNANT AND LACTATING WOMEN ............................ 82

FIGURE 5- 7 MCP UTILIZATION AMOUNT IN BICOL (UP TO JUNE IN 2016).................................. 84

FIGURE 5- 8 BARANGAY HOUSES IN CAMARINES SUR ................................................................ 84

FIGURE 5- 9 MMR AND IMR OF EASTERN VISAYAS .................................................................... 88

FIGURE 5- 10 RHU STAFF OF CAN-AVID MUNICIPALITY IN EASTERN SAMAR ............................... 95

FIGURE 5- 11 INTERVIEW WITH MAYOR ..................................................................................... 96

FIGURE 5- 12 BHS DESTROYED.................................................................................................. 96

FIGURE 5- 13 MCP BENEFIT PAYMENTS IN EASTERN SAMAR AND NORTHERN SAMAR ................ 99

FIGURE 5- 14 PHILHEALTH NORTHERN SAMAR OFFICE ........................................................... 99

FIGURE 5- 15 RURAL HOUSEHOLD INTERVIEWED BY THE STUDY ............................................ 102

TABLE 5- 1 PROVINCIAL POPULATIONS IN BICOL REGION (IN THOUSAND) ................................. 73

TABLE 5- 2 NUMBER OF MATERNAL DEATHS AT TERTIARY HOSPITALS ........................................ 74

TABLE 5- 3 PROPORTION OF FBD (%) BY PROVINCE/CITY ......................................................... 74

TABLE 5- 4 IMR BY PROVINCE/CITY........................................................................................... 75

TABLE 5- 5 REGISTERED NUMBER OF PUBLIC AND PRIVATE HOSPITALS (2015-2016) .................. 75

ix

TABLE 5- 6 STUDY SITES AND COMMUNITY INTERVIEWEES ......................................................... 76

TABLE 5- 7 NHIP COVERAGE BY SECTOR AND BY PROVINCE IN BICOL AS OF JUNE 2016 .............. 84

TABLE 5- 8 PROVINCIAL POPULATIONS IN EASTERN VISAYAS REGION (IN THOUSAND) ............... 87

TABLE 5- 9 PROVINCIAL FBD RATES IN EASTERN VISAYAS ......................................................... 88

TABLE 5- 10 REGISTERED HEALTH FACILITIES IN PROVINCES OF EASTERN VISAYAS (AS OF

AUGUST 2, 2016)................................................................................................................. 89

TABLE 5- 11 DELIVERIES AND MATERNAL DEATHS AT EVRMC ................................................. 90

TABLE 5- 12 MATERNAL AND CHILD HEALTH INDICATORS IN NORTHERN SAMAR ...................... 91

TABLE 5- 13 FACILITY BASED DELIVERY IN MUNICIPALITIES OF NORTHERN SAMAR PROVINCE .. 92

TABLE 5- 14 MATERNAL AND CHILD HEALTH INDICATORS IN EASTERN SAMAR.......................... 93

TABLE 5- 15 FACILITY BASED DELIVERY RATE IN EACH MUNICIPALITY OF EASTERN SAMAR

PROVINCE (2012 – JUNE 2016) .......................................................................................... 93

TABLE 5- 16 STUDY SITES AND COMMUNITY INTERVIEWEES ...................................................... 94

TABLE 5- 17 NUMBERS OF NHIP MEMBERS IN EASTERN VISAYAS (AS OF JUNE 2016) ................. 98

BOX 5- 1 STORY OF RHU MEDICAL DOCTOR OUTSIDE CASILI ZONE ....................................... 78

BOX 5- 2 BRTTH LEADERSHIP (STORY OF DOH REGIONAL OFFICER) ..................................... 79

BOX 5- 3 STORY OF PROVINCIAL HEALTH OFFICER ................................................................... 80

BOX 5- 4 HOME DELIVERY CASES .............................................................................................. 83

BOX 5- 5 EXPERIENCE OF A 35-YEAR-OLD WOMAN ................................................................. 103

BOX 5- 6 EXPERIENCE OF A 35-YEAR-OLD WOMAN ................................................................ 105

BOX 5- 7 EXPERIENCE OF A 19-YEAR-OLD WOMAN ................................................................. 105

CHAPTER 6

FIGURE 6- 1 BHS SUPPORTED BY JICA .................................................................................... 108

FIGURE 6- 2 BHS STAFF INTERVIEWED ..................................................................................... 111

FIGURE 6- 3 MCP-ACCREDITED BHS ...................................................................................... 111

TABLE 6- 1 LIST OF INTERVIEWEES .......................................................................................... 108

TABLE 6- 2 OUTCOME OF THE JICA PROJECT IN CORDILLERA ................................................. 109

TABLE 6- 3 OUTCOME OF THE JICA PROJECT IN EASTERN VISAYAS .......................................... 110

CHAPTER 7

FIGURE 7- 1 SDN HOUSEHOLD PROFILING .............................................................................. 117

FIGURE 7- 2 RECOMMENDED JICA NEW PROJECT AND PROJECT UPSCALING MECHANISM ....... 119

1

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Although the national infant mortality rate and under-five mortality rate have declined steadily,

the maternal mortality ratio and neonatal death remain high and regional disparities exist in the

Philippines. In the Philippine Health Agenda 2016-2022, President Duterte announced that the

new administration would guarantee good health for all life stages by setting effective Service

Delivery Networks and providing universal health insurance.

In 1995, the National Health Insurance Program (NHIP) was established, and as of the end of

June 2016, 90 percent of Filipinos were enrolled in NHIP. However, the out-of-pocket

expenditure rate is more than 50 percent, which is higher than many other Southeast Asian

countries. Moreover, the knowledge of the LGU staff, the health care providers and the people

is still limited and utilization rate remains low at 12 percent. The government budget increased

substantially in 2014 due to increased tax revenue from the Sin Tax Reform Law of 2012 and

about 40 percent of the indigent and near-indigent population are now sponsored by the national

government. Nonetheless, the total health expenditure for the richest quintile is more than twice

as much as that of the poorest quintile. The total health expenditure as a percentage of the Gross

Domestic Product (GDP) in the Philippines is lower than most developed countries, however,

comparable to other Southeastern Asian countries.

The Philippine health system is devolved and public health service providers are primarily local

government units (LGUs). The public health services are financed by central government

subsidy and the LGU budget. The LGU budget consists of local government tax revenues, user

fees at health facilities, and payments from health insurance corporations. Health service quality

highly depends on leadership of the executives of LGUs. Functional health service networks are

indispensable particularly for emergency obstetric care. However, coordination between the

primary health facilities and the referral hospitals within the multiple LGUs has been a

challenge in the devolved Philippine health system.

While institutional delivery has been increasingly popular in the Philippines, quite a few women

still prefer home delivery. There are geographical and cultural factors that affect their

preference; however, the important factor is financial. When a woman delivers at a facility, she

has to pay for medicine not in stock, some examinations, transportation fees, food for the

attendant family members, payment of the child care-takers, and loss of income while

hospitalized. These expenditures are a huge burden on poor families.

The survey team would recommend JICA to pursue the new technical assistance project, “UHC

enhancement in the MCH services” with two approaches: improved access to quality essential

health-care services and financial risk protection. Furthermore, a mechanism to fully up-scale

the good results of the project to the entire country should be also sought in the new project.

2

Chapter 1 Overview of the Survey

1-1 Background

The Aquino administration launched the national Universal Health Care policy (Kalusugan

Pangkalahatan, known as KP) in December 2010 to provide every Filipino with affordable and

quality health services particularly the most vulnerable and remote populations through three

strategic goals: 1) financial risk protection, 2) improved access to quality hospitals and health

care facilities, and 3) the attainment of health-related Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

The first goal, financial risk protection, is intended to insure all citizens through the

implementation of the National Health Insurance Program (NHIP) by the Philippine Health

Insurance Corporation (PhilHealth).

The new President Duterte recently introduced the Philippine Health Agenda 2016-2022 with

the theme “All for Health towards Health for All.” The Agenda aims at attaining Health-Related

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) Targets, Financial Risk Protection, Better Health

Outcomes and Responsiveness, and guarantees (1) All Life Stages & Triple Burden of Disease,

(2) Service Delivery Network, and (3) Universal Health Insurance.

According to PhilHealth, 92,624,502 people or 90 percent of the total population

1

had become

eligible beneficiaries of the NHIP by the end of June 2016 and the enrollment rate has been

increasing somewhat.

2

Since the Sin Tax Law (RA 10351) was passed in December 2012, the

increased tax revenue has enabled many of poor families to be enrolled as indigent members.

On the other hand, household out-of-pocket spending has increased by 150 percent from 2000 to

2012.

3

Although the out-of-pocket spending rate out of the total health expenditures has been

decreasing lately, household out-of-pocket spending was still as high as 44 percent, and NHIP’s

utilization rate

4

remains low at 12 percent as of December 31, 2015.

5

In addition, it is reported

that 7.7 percent of the households experienced catastrophic health expenditure in 2012 and the

proportion had increased three-fold from 2000.

6,7

This data reveals that NHIP enrollment has

not necessarily resulted in the improvement of access to health services and financial risk

protection.

1

On the basis of the Philippine 2015 Population Census, the total population of the Philippines as of

August 1, 2015 is 100,981,437.

2

PhilHealth. (2016). Stats and Charts, December 31, 2015.

3

Bredenkamp C. & Buisman L. R. (2016).

4

Utilization rate = unique member claims reimbursed/ total eligible members

5

PhilHealth. (2016). Stats and Charts, December 31, 2015.

6

ibid

7

Bredenkamp C. & Buisman L. R. (2016).

3

The government of Japan stated promotion of universal health coverage (UHC) as a vision of

Japan’s Strategy on Global Health Diplomacy in 2013. The government also declared that Japan

would take the lead in addressing global challenges including UHC, formulating international

goals and guidelines, and making active efforts to achieve the goals in the Development

Cooperation Charter in 2015.

Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) has been providing assistance to the Philippines

for the improvement of maternal and child health (MCH) especially in remote and poor areas,

such as the Cordillera Administrative Region and Eastern Visayas Region. While the evidence

has shown that the JICA projects have improved the MCH service delivery in the target areas, it

is suggested that mothers are still dying in childbirth due to personal, family and community

factors as well as healthcare system factors that hinder their accessibility to health services.

8

In

order for JICA to continue the efforts of MCH development in the context of the new

Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 3, aiming at reduction of maternal and neonatal mortality

and improved access to sexual and reproductive health-care services, and start contributing to

the new administration’s health agenda, JICA dispatched the data collection survey team to

clarify current issues affecting access to MCH services, particularly for the poor, and to explore

JICA’s future assistance in the Philippines to promote UHC in the area of MCH.

1-2 Objectives

The data collection survey had the following objectives:

1) To understand the current status of NHIP implementation in the Philippines and identify

issues preventing access to basic health services with a particular focus on MCH services

for the poor; and

2) To identify possible areas for JICA’s future assistance in strengthening MCH services and

promoting UHC in the Philippines.

1-3 Scope of the Survey

Based on the situation analysis and objectives described earlier, data collection activities of the

survey were undertaken within the scope described in Table 1- 1.

8

Saniel, O. P. & Bermudez, A. N. C. (2016, August). Why do mothers die? A Maternal Death Review

in Camarines Norte.

4

Table 1- 1 Scope of the Survey

1-4 Survey Areas

The JICA survey team reviewed the overall status of UHC

and MCH efforts of the Philippines in Manila, and drew

lessons learned from the currently conducted MCH project

in the Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR).

Moreover, the Bicol Region and Eastern Visayas Region

were selected as field data collection sites based on the

following criteria (see Table 1- 2):

Unsuccessful MCH indicators including facility- based

delivery (FBD), antenatal care (ANC) from skilled

providers and postnatal care (PNC) in the first two days

after birth according to National Demographic and

Health Survey (NDHS) 2013

20 High Poverty Sites announced by the Duterte

Administration as priority provinces

High ratio of geographically isolated and

disadvantaged area (GIDA), according to the

Department of Health (DOH)

Large population

Accessible from Manila

Acceptable security level based on JICA’s standards

(1) Heath sector analysis

Status and issues concerning the overall health sector especially MCH

Regional progress in achieving MCH indicators

Status of health system at regional level

Donor assistance

Health sector priorities under the new administration

(2) Status of basic health service provision and access for the poor through the NHIP

Basic information about the NHIP

Size of population covered by the NHIP

Health services covered by the NHIP

Proportion of costs covered by the NHIP

(3) Analysis of factors affecting access to health services particularly economic access

Systems of DOH and PhilHealth to address the issue of economic access

Situation of out-of-pocket health expenditure paid by pregnant women

Implementation status of the No Balance Billing Policy at health facilities

(4) Suggestion of JICA’s future cooperation program

Means of transportation and transportation fees for pregnant women’s access and referral

to health facilities including hospitals, RHUs and BHS

Psychological barriers for pregnant women at the time of referral to health facilities

including hospitals, RHUs and BHS

Level of awareness of patients and service providers on the MCH service package and

primary care benefits

Figure 1- 1 Map pf the Philippines

5

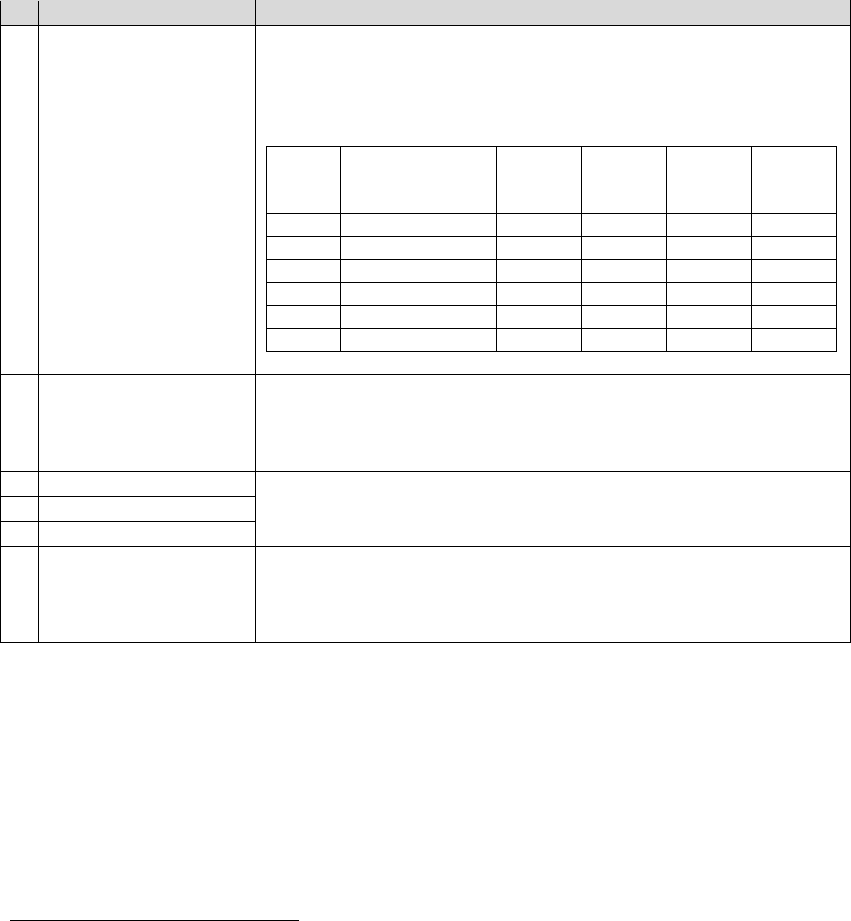

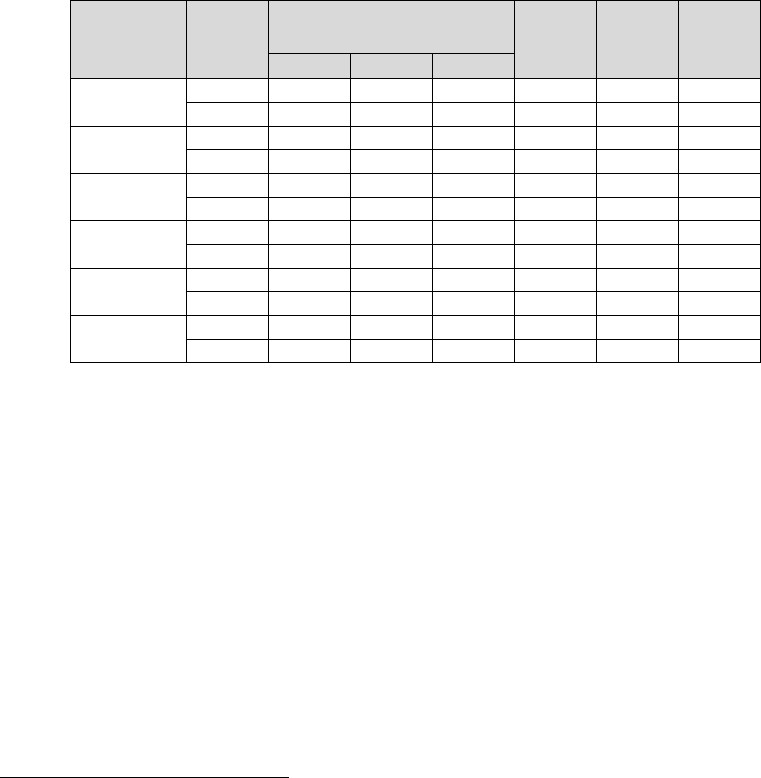

Table 1- 2 Selection Criteria of the Field Data Collection Target Areas

9

Region

2015

Population

1

FBD

2

ANC

2

PNC

2

GIDA(%)

3

High

Poverty

Sites

%

Rank

%

Rank

%

Rank

Rank

1.

Mimaropa - 4B

2,963,360

37

15

91

15

50

15

7

―

2.

Soccksargen - 12

4,545,276

49

13

92

14

54

14

14

〇

3.

Zamboanga Peninsula - 9

3,629,783

43

14

94

13

55

13

14

〇

4.

Northern Mindanao - 10

4,689,302

53

10

95

12

58

12

12

〇

5.

Caraga - 13

2,596,709

56

9

97

9.5

63

11

24

―

6.

Cagayan Valley - 2

3,451,410

51

12

97

7

67

10

20

―

7.

Bicol Region - 5

5,796,989

51

11

97

9.5

74

7

19

〇

8.

Eastern Visayas - 8

4,440,150

62

7

96

11

77

5

9

〇

9.

Davao Region - 11

4,893,318

63

6

98

5

73

9

14

〇

10.

Western Visayas - 6

4,477,247

61

8

98

3

73

8

21

〇

11.

Calabarzon - 4A

14,414,774

66

5

97

8

77

4

2

〇

12.

Ilocos Region - 1

5,026,128

67

4

97

6

78

3

16

〇

13.

Central Luzon - 3

11,218,177

68

3

98

4

76

6

11

―

14.

Central Visayas- 7

6,041,903

72

2

98

1

83

2

5

〇

15.

CAR

1,722,006

75

1

98

2

83

1

42

〇

Source:

1

The Philippine Population Census (2015),

2

National Demographic and Health Survey (2013),

3

Bureau of Local Health Development, DOH,

4

DOH

1-5 Methodology

The survey consisted of a literature review and field data collection to derive situation analysis

and strategic recommendations for JICA’s future assistance in the Philippines:

(1) Literature review

Existing academic research papers and reports by government, donors and

non-governmental organizations (NGOs) on the subjects mentioned in Table 1- 1 were

collected and analyzed throughout the survey period.

(2) Field data collection

The JICA survey team conducted interviews and collected materials at the Philippine

Government offices, including the Department of Health (DOH), PhilHealth, the

Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD), the Department of Interior and

Local Government (DILG) and the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), and development

partners at the national level. At the sub-national level, the survey team collected

information through key informant interviews (KIIs) and focus group discussions (FGDs)

at the DOH/PhilHealth Regional Offices, other government offices, local government units

(LGUs), health facilities, NGOs, community members and any other relevant parties.

9

National Capital Region and ARMM are not included in the table as they are not likely to be JICA

project target sites. NIR is also not included as it was newly created in 2015.

6

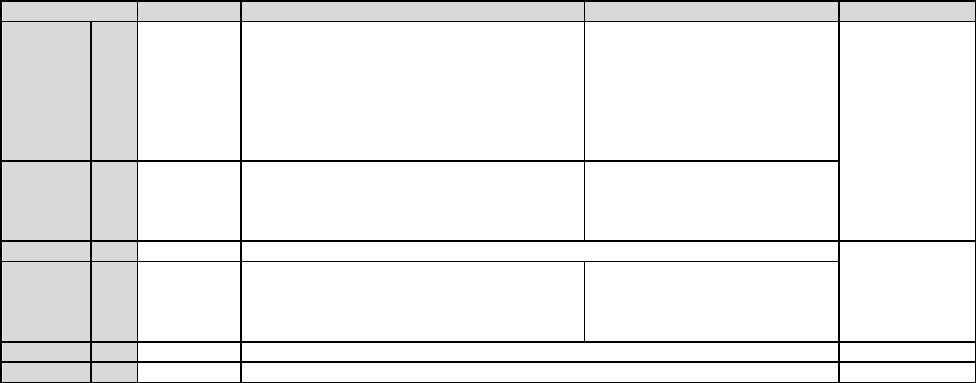

Table 1- 3 shows categories and sub-categories, sources and collection methods of data

collected in the survey.

Table 1- 3 List of Data to be Reviewed During the Survey

Data Category

Data Sub-Category

Data Source

Data

Collection

Method

1

Status and issues of

the health sector

especially MCH

Overview of the health sector

Achievements and challenges

pertaining to MCH

Online

Statistical data

Japanese experts

Desk

review

KII

Regional Progress in

achieving MCH

indicators

MMR

IMR

MCH service utilization rates

Online

Statistical data

Status of health

system at regional

level

System of health service provision

Human resources

Budget

Number of NHIP-accredited facilities

Online

Statistical data

Japanese experts

Donor assistance

Status of assistance in health financing

Status of assistance in MCH

Status of assistance in health system

Online

Japanese experts

New administration’s

health sector priorities

Priority issues on MCH

Other priority issues on health

Online

Japanese experts

2

Basic information

about the NHIP

Organization and structure

Financial resources and budget

Payment mechanisms

Accreditation system

Awareness-raising activities

Online

DOH and PhilHealth

Experts

Desk

review

KII

Size of population

covered by the NHIP

Enrollment and utilization rates of

each program (particularly for

indigents)

Online

DOH and PhilHealth

Beneficiaries

including indigents

Desk

review

FGD

KII

Enrollment rates in each region

DOH and PhilHealth

Desk

review

KII

Reasons for not enrolling

Community members

not enrolled in the

NHIP

FGD

KII

Characteristics of NHIP populations

PhilHealth

KII

Health services

covered by the NHIP

Details of benefits and packages

Online

PhilHealth

Desk

review

KII

Proportion of costs

covered by the NHIP

Details of out-of-pocket spending

DOH and PhilHealth

NHIP members

Details of costs covered by LGUs

DOH/LGU and

PhilHealth

Health facilities

Measures for indigents not enrolled in

the NHIP

Health facilities

PhilHealth

Indigents who are not

enrolled in the NHIP

Desk

review

FDG

KII

7

Data Category

Data Sub-Category

Data Source

Data Collection

Method

3

Means of

transportation and

transportation fees

for pregnant

women’s access and

referral to health

facilities

Distance and conditions of

infrastructure between facilities at

different levels

DOH/LGU

Healthcare

providers/BHWs

Pregnant and

lactating women

Barangay councilors/

Chairmen

Donors/NGOs

PhilHealth

Community members

Desk review

KII

FGD

Transportation options and time

required

Transportation costs and household

income sources/levels

Existing transportation support by

government/donors

Psychological

barriers for pregnant

women at the time of

referral to health

facilities

Images/perceptions of health facilities

and staff

DOH/LGU

Healthcare providers/

BHWs

Pregnant and

lactating women

TBAs

Traditional leaders

Donors/NGOs

Actual experiences at or feedback on

health facilities (including what they

heard from families and friends)

Determining factors for referral

Household decision-making on referral

Coping strategies when referral is not

utilized

DOH and

PhilHealth’s systems

to address the issue

of economic access

DOH and PhilHealth’s measures to

address the issue

Online

DOH and PhilHealth

Community members

DOH’s measures to improve economic

access to health services other than the

NHIP (such as through social security

and anti-poverty systems)

Online

DOH and PhilHealth

Desk review

KII

DOH’s systems and mechanisms on

referral and emergency transport

LGU’s systems to support

transportation fees

DOH/LGU

KII

Details of PhilHealth’s benefits and

packages (in relation to economic

access)

PhilHealth

Desk review

KII

Out-of-pocket

expenses paid by

pregnant women

Fees paid at health facilities for ANC,

delivery and PNC services

Women who gave

birth in the past year

DOH and PhilHealth

Health facilities

KII

FGD (during

PNC and at

community)

Reimbursements from the NHIP for

healthcare expenses related to ANC,

delivery and PNC services

Women who gave

birth in the past year

PhilHealth

KII

FGD (during

PNC and in

community)

Implementation

status of the No

Balance Billing

Policy at hospital

level

Healthcare providers’ level of

awareness of the No Balance Billing

Policy

Healthcare providers

KII

Implementation status of the No

Balance Billing Policy

Health facilities

DOH/LGU

Patients

KII

FGD

Awareness levels of

patients and

healthcare providers

regarding the MCH

service package and

primary care benefits

Awareness levels of pregnant women

and healthcare providers on the MCH

service package

Healthcare

providers/BHWs

Pregnant and

lactating women

Patients

Barangay councilors/

Chairmen

Donors/NGOs

Awareness levels of patients and

healthcare providers on the primary

care benefits

8

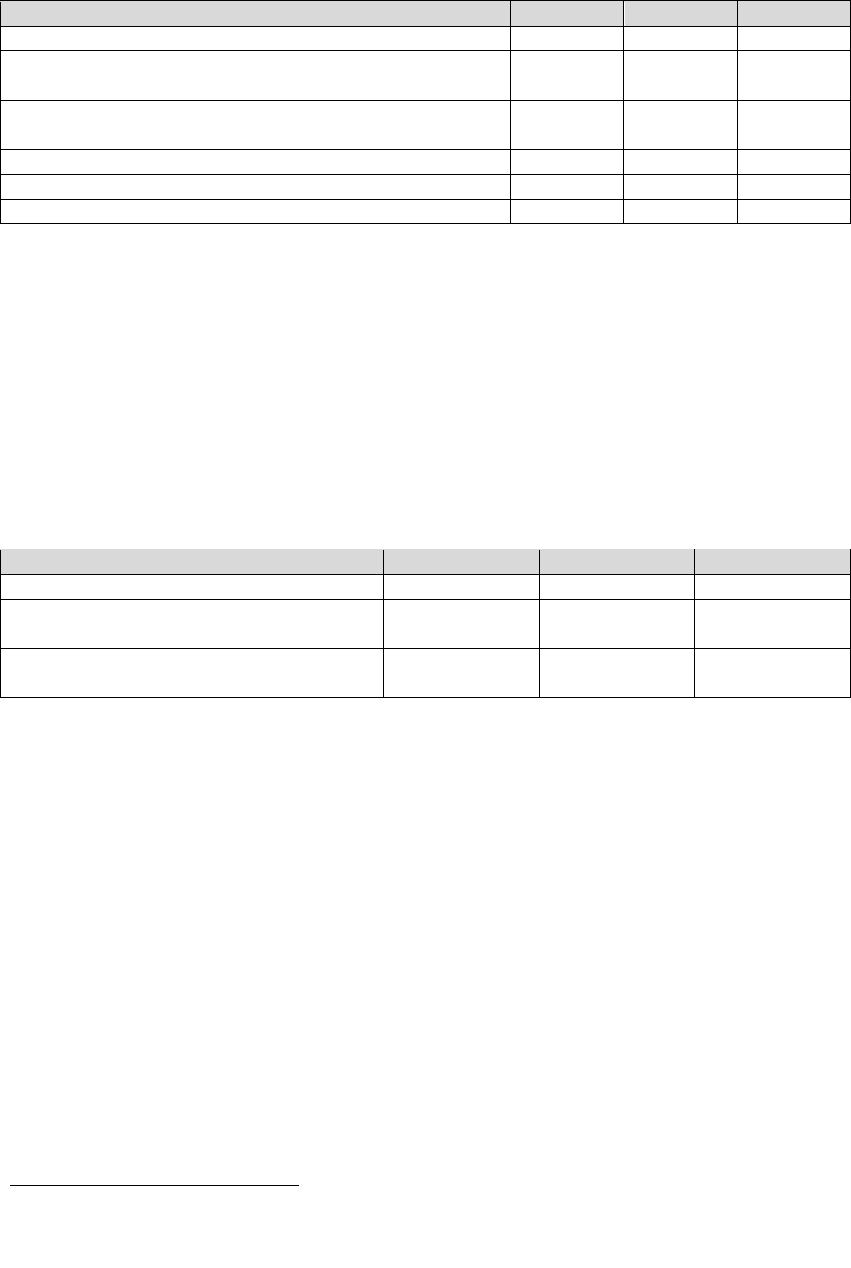

The key informants interviewed in the survey are listed in Table 1- 4.

Table 1- 4 List of Key Informants During the Field Data Collection

Informants

Government

DOH (national/regional officers)

LGU (provincial/city/municipal health officers)

Healthcare providers at DOH’s

regional/provincial/district/municipal hospitals, medical

centers, RHUs and BHS

BHWs

Barangay Chairmen and Councilors

Community Health Team (CHT)

PhilHealth (national and LGU levels)

DSWD (national/regional/provincial/municipal

officers)

Development

partners

WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank, ADB, EU,

USAID

NGOs

Community

Pregnant and lactating women

TBA

Traditional/religious leaders

Patients at health facilities

Community-based organizations/women’s groups

Other

Private hospitals and clinics covered by PhilHealth in

survey areas

Private insurance companies

JICA Office, JICA Experts and the Embassy of Japan

Ambulatory service providers (such as Lifeline Rescue)

Universities and think tanks

1-6 Survey Team

The survey team consists of the members in Table 1- 5.

Table 1- 5 Survey Team Members

Name

Area of work

Affiliation

Ms. Haruyo Nakamura

Team Leader/UHC

Global Link Management, Inc.

Ms. Akiko Hirano

MCH /Health System Analysis

Global Link Management, Inc.

Ms. Nami Takashi

MCH /Needs Analysis

Global Link Management, Inc.

Mr. Shizuma Yokozawa

Health Financing

Deloitte Tohmatsu Financial Advisory LLC

1-7 Survey Schedule

The survey was conducted from July to December 2016. During this period field data

collections were executed in the Philippines for three times. Please see Attachments 1-4 for the

detailed schedules of the first to third field data collections. The work flow of the entire survey

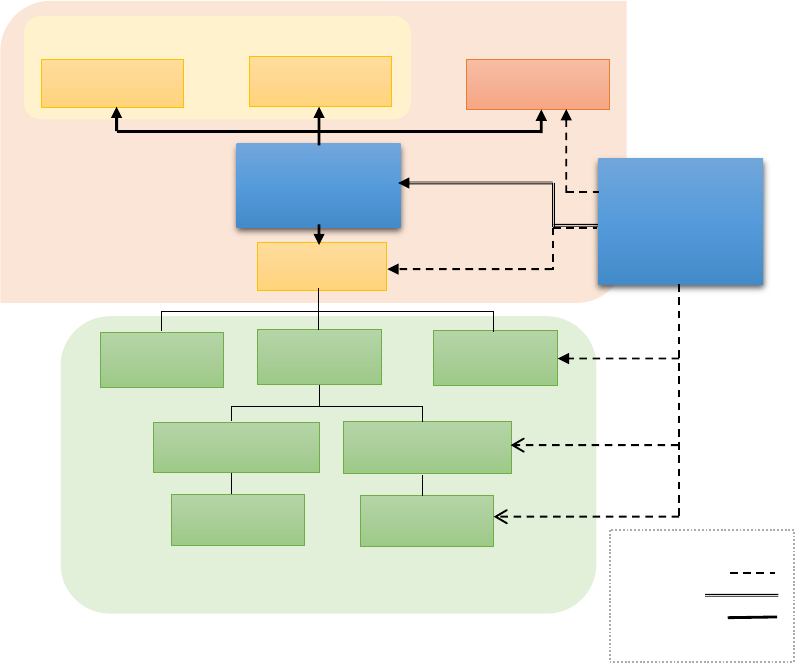

is shown in Figure 1- 2.

9

Figure 1- 2 The Work Flow of the Data Collection Survey on UHC in the Philippines

Month

Deliverable Tasks in Japan Tasks in the Philippines

JUL

AUG

SEP

OCT

NOV

DEC

・Develop and finalize the inception report

・Desk review on the health sector situation

・Prepare for the field data collection

(1) Preparation

Inception

Report

・Brief JICA Philippines, DOH etc. on the inception report

・Interview DOH, PhiliHealth, donors etc. on the system of health

care and MCH service delivery and access for the poor

(2) First Field Data Collection

・Interview LGUs, health facilities and communities in target

regions (CAR, Eastern Visayas and Bicol Region) on factors

affecting economic access to MCH services

・Analysis and documentation of the first field survey

・Prepare for the second field survey

(4) Second Field Data Collection

Summary

of Results

Final

Report

Reporting to

JICA HQ

(3) Documentation and Preparation

・Discussion with JICA Philippines and DOH on the summary

・Follow-up data collection

(5) Drafting of a Summary of Results from the Field Data Collection

・Finalize the result summary

・Devise JICA’s future assistance

(7) Documentation and Analysis

・Develop a final report

(8) Finalization

Consultation

with JICA HQ

(6) Third Field Data Collection

10

Chapter 2 Socio-Economic Situation in the Philippines

2-1 Geography, Ethnicity and Religion

The Philippines is an archipelago comprised of 7,107 islands in Southeast Asia. Its terrain is

primarily mountainous with narrow to extensive coastal lowlands. It has a tropical and maritime

climate, characterized by relatively high temperatures, high humidity and abundant rainfall.

Because of its location in the typhoon belt of the Western Pacific, the Philippines experiences

an average of twenty typhoons annually during its rainy season, from June to November. In

addition, the country is along the “Pacific Ring of Fire,” where large number of earthquakes and

volcanic eruptions occur. These factors combine to make the Philippines one of the most

disaster-prone countries on the globe.

10

According to the 2010 Census of Population and Housing, 92.6 percent of the Filipinos are

Christian, 80.6 percent of which are Roman Catholic, 5.6 percent are Muslim and 0.05 percent

are Buddhist. There are approximately 180 ethnic groups which have their own languages. The

largest linguistic group is Tagalog, which accounts for 24.4 percent of the population. Other

ethnic groups include Cebuano, Ilocano, Hillgaynon (Ilongo), Bisaya, Bicol and

Lineyte-Samarnon (Waray). The official language of the Philippines is Filipino, derived from

Tagalog and English.

2-2 Population Statistics and Future Projections

The total population of the Philippines was 76,506,928 in 2000, 92,337,852 in 2010 and

100,981,437 in 2015 (see Figure 2- 1). The average population growth rate during the period

varies from the highest in Calabarzon Region at 2.85 percent to the lowest in Negros Island

Region at 1.14 percent (see Figure 2- 2).

11

The population in 2016 is estimated to be

102,250,133 (population growth rate: 1.54 percent, population density: 343 persons per km

2

)

and projected to continuously increase to 148,260,478 by 2050.

12

10

Kwon S. & Dodd R. (Eds.). (2011). The Philippines Health System Review, WHO Health Systems in

Transition.

11

The Philippine 2015 Population Census.

https://psa.gov.ph/content/highlights-philippine-population-2015-census-population.

12

Worldometers (www.Worldometers.info) Elaboration of data by United Nations, Department of

Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision.

(Medium-fertility variant).

11

Source: Department of Economic and

Figure 2- 1 Population pyramid of the Philippines, 2015 (in thousands)

Social Affairs, Population Division, United Nations

Figure 2- 2 National and Regional Population in the Philippines (2000-2015)

Source: The Philippine 2015 Population Census. https://psa.gov.ph/content/highlights-philippine-population-2015-census-population.

0 2,000 4,000 6,000

02,0004,0006,000

0-4

10-14.

20-24

30-34

40-44

50-54

60-64

70-74

80-84

Men Women

0 4,000,000 8,000,000 12,000,000 16,000,000

REGION XIII (Caraga)

AUTONOMOUS REGION IN MUSLIM MINDANAO (ARMM)

REGION XII (SOCCSKSARGEN)

REGION XI (DAVAO REGION)

REGION X (NORTHERN MINDANAO)

REGION IX (ZAMBOANGA PENINSULA)

REGION VIII (EASTERN VISAYAS)

NEGROS ISLAND REGION (NIR) 1

REGION VII (CENTRAL VISAYAS)

REGION VI (WESTERN VISAYAS)

REGION V (BICOL REGION)

REGION IV-B (MIMAROPA)

REGION IV-A (CALABARZON)

REGION III (CENTRAL LUZON)

REGION II (CAGAYAN VALLEY)

REGION I (ILOCOS REGION)

CORDILLERA ADMINISTRATIVE REGION (CAR)

NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION (NCR)

TOTAL POPULATION 1-Aug-15 TOTAL POPULATION 1-May-10 TOTAL POPULATION 1-May-00

0 4,000,000 8,000,000 12,000,000 16,000,000

REGION XIII (Caraga)

AUTONOMOUS REGION IN MUSLIM MINDANAO (ARMM)

REGION XII (SOCCSKSARGEN)

REGION XI (DAVAO REGION)

REGION X (NORTHERN MINDANAO)

REGION IX (ZAMBOANGA PENINSULA)

REGION VIII (EASTERN VISAYAS)

NEGROS ISLAND REGION (NIR) 1

REGION VII (CENTRAL VISAYAS)

REGION VI (WESTERN VISAYAS)

REGION V (BICOL REGION)

REGION IV-B (MIMAROPA)

REGION IV-A (CALABARZON)

REGION III (CENTRAL LUZON)

REGION II (CAGAYAN VALLEY)

REGION I (ILOCOS REGION)

CORDILLERA ADMINISTRATIVE REGION (CAR)

NATIONAL CAPITAL REGION (NCR)

TOTAL POPULATION 1-Aug-15 TOTAL POPULATION 1-May-10 TOTAL POPULATION 1-May-00

12

The proportion of age categories 0-14 years, 15-64 years and 65+ years are 31.9 percent, 63.5

percent and 4.6 percent, respectively, in 2015. The child dependency ratio

13

is 50.3, the old-age

dependency ratio

14

is 7.2, and the total dependency ratio is 57.5.

15

The total fertility rate is

3.04, the under-five mortality rate is 30 per 1,000 live births, and average life expectancy is

estimated to be 68 years.

16

The total fertility rate is similar to Japan’s in 1951-1952.

17

Life expectancy

18

and the

population proportions of 0-14 years and 15-64 years are similar to Japan in 1960; however, the

proportion of people 65+ years is lower than that of Japan in 1960 at 5.7.

19

Aging is slowly becoming an issue in the Philippines.

20

The Philippines is forecast to become

an aging society with 7 percent of aged people (65+ years) in 2030-2035 and an aged society

with 14 percent of aged people in 2070-2075. The doubling time

21

is projected to be 35 to 45

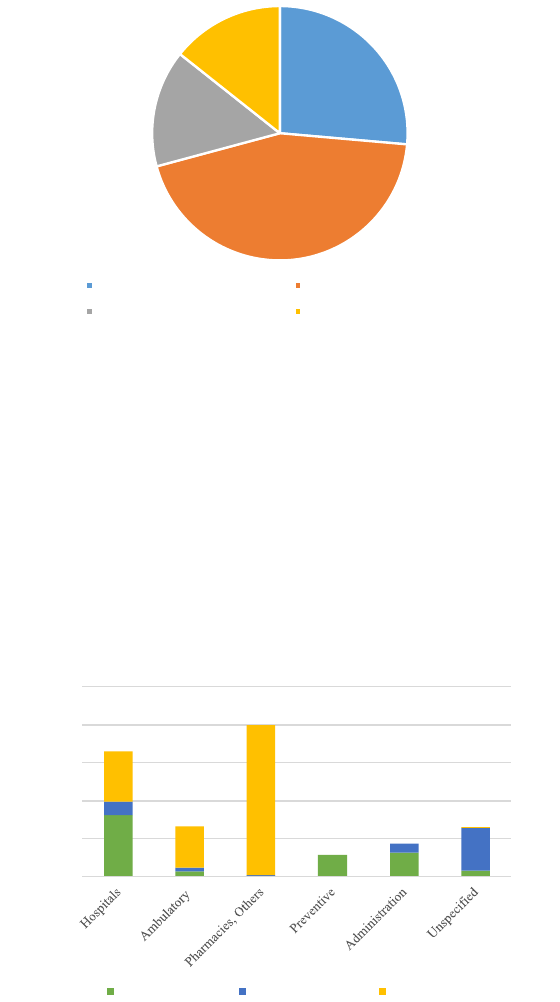

years,

22

which is much longer than that of Japan at 24 years.

23

It is predicted that the labor force ratio (15-64 years) will be 66.7 percent in 2055 at the highest

point and then will decrease, while the dependency ratio will be 33.3 percent at the lowest in the

same year and then will increase.

24

Japan experienced the same transition in the early 1990s.

25

13

The child dependency ratio is an age-population ratio of children under the age of 15 and those

typically in the labor force (the productive part). It is used to measure the pressure on the productive

population.

14

The old-age dependency ratio is an age-population ratio of those over the age of 64, not in the labor

force, and those typically in the labor force (the productive part). It is used to measure the pressure on

the productive population.

15

The Philippine 2015 Population Census.

https://psa.gov.ph/content/highlights-philippine-population-2015-census-population.

16

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2015). World

Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision. Volume II: Demographic Profiles.

17

National Institute of Population and Social Security Research. 2016. Population Statistics.

http://www.ipss.go.jp/syoushika/tohkei/Popular/P_Detail2016.asp?fname=T04-03.htm.

18

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Abridged life table.

http://kaiwa-kouza.com/contents/sub/statistics/longevity.html.

19

Statistics of Japan 2016, Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications.

http://www.stat.go.jp/data/nihon/02.htm

20

All the population estimates here are moderate-range estimates.

21

Number of years required for the proportion of the aged population to move from 7% to 14%. It is an

indicator that shows the speed of aging in each country.

22

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Interactive data of

World Population Prospects, the 2015 Revision. https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/.

23

National Institute of Population and Social Security Research. 2012. Population Statistics.

http://www.ipss.go.jp/syoushika/tohkei/Popular/P_Detail2012.asp?fname=T02-18.htm

24

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Interactive data of

World Population Prospects, the 2015 Revision. https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/.

25

Statistics of Japan 2016, Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications.

http://www.stat.go.jp/data/nihon/02.htm

13

In the Philippines, child dependency is currently much higher than old age dependency (child

dependency: 50.3, old-age dependency: 7.2), however, it will become equal in 2090 (both child

dependency and old-age dependency: 31.1) and then old-age dependency will become slightly

higher.

26

Japan experienced the same transition in the late 1990s.

27

2-3 Poverty and Economic Disparity

The Gross National Income (GNI) of the Philippines was US$357 billion

28

in 2015, GNI per

capita was US$3,540,

29

and the real GDP growth rate has been on average 6 percent from 2010

to 2015. The Philippines is categorized as a “lower-middle-income economy”

30

by the World

Bank.

31

In the Philippines, the poverty incidence

32

was estimated at 21.6 percent in 2015.

33

Although

the estimate was improved from 2012 at 25.6 percent, another poverty data, the poverty

headcount ratio, has not shown much change in the past decade in the country, while other

Southeast Asian countries, such as Cambodia, Thailand, Vietnam and Laos, have shown

progress (see Figure 2- 3). The Philippines’ poverty headcount ratio is in fact one of the highest

in the region today.

26

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Interactive data of

World Population Prospects, the 2015 Revision. https://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/.

27

Statistics of Japan 2016, Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications.

http://www.stat.go.jp/data/nihon/02.htm

28

At the time of the US$ market price.

29

Calculated using Atlas method of the World Bank (Converted to the current US$).

30

World Bank Open Data. http://data.worldbank.org/

31

The World Bank’s country classification by income level takes place in July every year and it uses

GNI per capita of the previous years as an indicator. For the current 2017 fiscal year, lower

middle-income economies are defined as those with a GNI per capita, calculated using the World

Bank Atlas method, of between $1,026 and $4,035.”

32

Poverty incidence is the proportion of people below the poverty line to the total population. The

poverty line refers to the minimum income required to meet food and non-food requirements. In 2015,

a family of five needed at least PhP 9,064, on average, every month to meet both basic food and

non-food needs. Source: Philippine Statistics Authority. https://psa.gov.ph/poverty-press-releases.

33

Philippine Statistics Authority. (2016). Philippine Poverty Statistics.

https://psa.gov.ph/poverty-press-releases

14

Figure 2- 3 Trends of poverty headcount ratio at national poverty lines (% of population)

in ASEAN countries in 1997-2014

Source: World Bank. The World Development Indicators

Figure 2- 4 Trends of poverty gap at national poverty lines (%)

in ASEAN countries in 1997-2012

Source: World Bank. The World Development Indicators

Whereas the poverty gap ratio

34

in 2012 was 5.1 percent, which had slightly improved since

2003, showing that the depth and incidence of poverty in the country has been somewhat

mitigated in the past decade. However, the country’s progress is still minimal as compared with

other Southeastern countries, such as Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam, and the Philippine poverty

gap ratio was second highest among these nations in 2012 (see Figure 2- 4).

The GINI Index, which measures the degree of inequality in the distribution of family income in

a country, shows that income is distributed quite unequally in the Philippines, at the highest

34

Poverty gap ratio is the mean shortfall of the total population from the poverty line (counting the

non-poor as having zero shortfall), expressed as a percentage of the poverty line. This measure reflects

the depth of poverty as well as its incidence.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

1997 2000 2002 2003 2004 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Philippines Cambodia Lao PDR Thailand Vietnam

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

1997 2002 2003 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

Philippines Cambodia Lao PDR Vietnam

15

after 1996, and it has not improved over the past three decades. In fact, the Philippines’ family

income is the most unequally distributed in all of Southeast Asia (see Figure 2- 5).

Figure 2- 5 Trends of GINI Index (World Bank estimate)

in Southeast Asian countries in 1981-2012

Source: World Bank. The World Development Indicators

2-4 Industrial Structure and Labor Market

In the Philippines, the composition ratio by industry to GDP in 2014 was as follows:

manufacturing (20.6%), trade (17.7%), agriculture (11.3%), finance (7.8%), and construction

(6.6%). The composition ratio has not changed in the past three decades.

35

The labor force

36

(ages 15-64) of the Philippines in 2014 was 41,379,000 people. Among the

labor force, 38,651,000 people were employed and 2,728,000 were unemployed. The

unemployment rate among the labor force is 6.6%.

37, 38

35

Asia Development Bank 2015. Key Indicators for Asia and the Pacific 2015.

http://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/175162/phi.pdf

36

All persons who are 15 years old and over and are reported as (1) without work, (2) currently

available for work, and (3) seeking work or not seeking work due to valid reasons.

37

Proportion of people who are both jobless and looking for a job.

38

Asia Development Bank 2015. Key Indicators for Asia and the Pacific 2015.

http://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/175162/phi.pdf

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

1981 1985 1988 1990 1991 1992 1994 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2002 2003 2004 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

Philippines Cambodia Lao PDR Thailand Vietnam

16

Chapter 3 Overview of the Health Sector

3-1 Health System with a Focus on Maternal and Child Health

(1) Health Governance

The Philippine health system is comprised of five administrative bodies. The Department

of Health (DOH) in the central government is in charge of the development of policies,

regulations and guidelines, and the provision of tertiary health care. The provincial

governments are responsible for secondary health care, and the municipal/city

governments are in charge of primary health care. The general term for a provincial

government and a municipal/city government is a local government unit (LGU). Each

municipality/city is divided into barangays and the barangay health station (BHS) provides

public health services as the closest facility to the people.

In principle, LGU health personnel are employed and deployed by the LGUs. However,

LGU health facilities also have human resources assigned by DOH, such as Development

Management Officers (DMOs) who provide technical assistance to the municipalities, and

monitor and report DOH programs, Nurses and Midwives posted at Rural Health Units

(RHUs) and BHSs.

Figure 3- 1 Health Governance Structure in the Philippines

Source: Global Link Management

There are two types of health service networks in the Philippines, namely Inter Local

Health Zone (ILHZ) and Service Delivery Network (SDN). ILHZ was adopted in the

Philippines based on the District Health System

39

advocated by World Health

Organization (WHO) in 1986, aiming at promoting coordination between the primary

39

The means to achieve the end of an equitable, efficient and effective health system based on the

principles of the primary health care (PHC) approach.

DOH

DOH Regional

Offices

Provincial Health

Offices

Municipal/City Health Offices

Barangay

Policy formulation, Guidance, Tertiary

Health Care Providsion: Specialty,

Regional & Training Hospitals

Primary Health Care

Provision: BHS

Secondary & Primary &Health

Care Provision: Minicipality/City

Hospitals, RHU, Infirmary

Secondary Health Care Provision:

Provincial & Distrcit Hospitals

Development

Management Officers

Nurse/ Rural Health

MW Deployment

Program

17

health facilities and the referral hospitals within the multiple LGUs in order to ensure the

access of communities to better health services. Meanwhile, SDN was announced in

Administrative Order No. 2014-0046 in 2014 during the Aquino Administration as a health

service networking system established by the provincial or municipal government with the

participation of the private sector. DOH reportedly planned to redefine the detail roles and

functions of SDN in 2016 and scale up its implementation nationwide.

40

DOH uses the LGU Health Score Cards with 30 indicators (see Attachment 5) as a tool of

Monitoring & Evaluation on Equity & Effectiveness for each local health system. DOH

requires LGUs to develop a three-year plan called the Local Investment Plan for Health

(LIPH). The LIPH was introduced in 2014 to strengthen local health planning with

significant consideration for building the capacities of health managers in the local

government units (LGUs). The Annual Operational Plan (AOPs) is prepared every year of

the planning cycle and the Service Level Agreement is signed. The results of the LGU

Score cards are primarily used for the planning process. For LGUs whose scores of

selected LGU Score Card indicators are positive, performance based grants are provided

by the Bureau of Local Health Development, DOH. The data for LGU Score Cards are

collected by the Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG) staff that have

offices at the municipality/city level.

41,42

(2) Health Policies

Under the Aquino Administration, the Government of the Philippines placed Universal

Health Care (Kalusugan Pangkalahatan, known as KP) as a principle of national health

policy and promoted to achieve the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

The new Duterte Administration recently presented the Philippine Health Agenda

2016-2022, as shown in BOX 3- 1.

40

Interview with the Bureau of Local Health Systems Development, DOH (August 5, 2016).

41

Interview with the Department of Interior and Local Government (August 1, 2016).

42

Interview with the Bureau of Local Health Systems Development, DOH (August 5, 2016).

18

BOX 3- 1 Philippines Health Agenda 2016-2022

~ All for Health towards Health for All ~

Goals:

1. Ensure the best health outcomes for all, without socio-economic,

ethnic, gender and geographic disparities

2. Promote health and deliver healthcare through means that

respect, value and empower clients and patients as they interact

with the health system

3. Protect all families especially the poor and vulnerable against the

high cost of healthcare

Values: Equity, quality, efficiency, transparency, accountability,

sustainability and resilience

Guarantees:

1. Population- and individual-level interventions for all life stages

*

that promote health and wellness, prevent and treat the triple

burden of diseases,

**

delay complications, facilitate rehabilitation and provide palliation

2. Access to health interventions through functional Service Delivery Networks (SDNs)

***

3. Financial freedom when accessing these interventions through Universal Health Insurance

Strategy:

dvance Quality, Health Promotion and Primary Care

over all Filipinos against Health-Related Financial Risk

arness the Power of Strategic Human Resources for Health Development

nvest in eHealth and Data for Decision-Making

nforce Standards, Accountability, and Transparency

alue All Clients and Patients, especially the Poor and Vulnerable

licit Multi-sectoral and Multi-stakeholder support for Health

*

All Life Stages refers to services for pregnant women, children, adolescents, adults and older persons.

**

Triple Burden of Disease pertains to the (1) communicable diseases and neglected tropical diseases, (2)

non-communicable diseases, and (3) problems related to globalization, urbanization and

industrialization, including injuries and mental illness.

***

SDNs 1) consist of primary care networks (PCNs) linked to Level 3 hospitals, 2) ensure well-equipped

and fully-staffed network of health facilities, 3) render services that are compliant with clinical practice

guidelines and 4) practice gatekeeping and utilize telemedicine to expand specialty service.

Source: DOH Office of the Secretary & DOH Health Policy Development and Planning Bureau. (2016).

Philippine Health Agenda 2016-2022 Healthy Philippines 2022.

The Philippine government agencies, including DOH, determine their agenda through the

cabinet secretaries for approval of the President based on his 10-point socioeconomic

agenda (see BOX 3- 2). This 10-point agenda is the basis for the Philippine Development

Plan, the country’s multi-sectoral development plan. The Philippine Health Agenda

contributes to numbers 7 and 10 of the 10-point agenda. The Philippine Health Agenda

A

C

E

V

E

I

H

STRATEGY

GOALS + VALUES

3 GUARANTEES

Service Delivery Network

All Life Stages &

Trip le Burden of Diseases

Universal Health Insurance

19

2016-2022 will be part of the Philippine Development Plan 2017-2022, under the Chapter

on Social Development.

43

BOX 3- 2 The 10-point Socioeconomic Agenda of President Duterte

1. Continue and maintain current macroeconomic policies, including fiscal, monetary, and trade

policies.

2. Institute progressive tax reform and more effective tax collection, indexing taxes to inflation.

A tax reform package will be submitted to Congress by September 2016.

3. Increase competitiveness and the ease of doing business. This effort will draw upon successful

models used to attract business to local cities (e.g., Davao) and pursue the relaxation of the

Constitutional restrictions on foreign ownership, except as regards land ownership, in order to

attract foreign direct investment.