Chapman University Digital Chapman University Digital

Commons Commons

Student Scholar Symposium Abstracts and

Posters

Center for Undergraduate Excellence

Spring 5-4-2023

How Does the Presence of Divorce Affect Children’s Anxiety How Does the Presence of Divorce Affect Children’s Anxiety

Surrounding Romantic Relationships? Surrounding Romantic Relationships?

Hannah Fereday

Chapman University

Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/cusrd_abstracts

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Fereday, Hannah, "How Does the Presence of Divorce Affect Children’s Anxiety Surrounding Romantic

Relationships?" (2023).

Student Scholar Symposium Abstracts and Posters

. 580.

https://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/cusrd_abstracts/580

This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Undergraduate Excellence at

Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Scholar Symposium Abstracts

and Posters by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please

contact [email protected].

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

1

How Does the Presence of Divorce Affect Children’s Anxiety Surrounding Romantic

Relationships?

Hannah P. Fereday

Chapman University

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

2

Abstract

The past few decades have seen a significant increase in the rates of divorce, with factors

such as changing societal norms, economic pressures, and individual desires for personal

fulfillment influencing this trend. Children of divorced parents often experience a range of

emotional, social, and psychological effects that can have an impact on their well-being. Past

literature has found that individuals who experience parental divorce suffer from increased

behavioral difficulties, less time with father figures, and feel more hesitant towards relationship

commitment than individuals who do not have divorced parents. The current study specifically

inspected how parental divorce can affect people and how the social learning theory impacts an

individual’s thoughts toward divorce and future romantic relationships. This study utilized

survey research to collect data for analysis from students at Chapman University to determine the

severity of effects on individuals due to parental divorce. Of the four hypotheses proposed, none

were supported with statistically significant data. Despite not finding statistically significant

results in this study, it is important to have intervention groups/organizations to better support

people who have experienced parental divorce. Past studies should prompt therapy interventions

to be accessible to any child who experiences parental divorce, with therapy being offered at

schools or private therapists to prevent any negative consequences.

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

3

How Does the Presence of Divorce Affect Children’s Anxiety Surrounding Romantic

Relationships?

With divorce no longer being viewed as taboo in some cultures, the number of marriages

in the United States resulting in divorce has reached a high of 50 percent, with the average

marriage lasting only eight years (Divorce statistics and facts, 2022). Due to these increasing

rates, more children are being forced to live with the aftermath of separated families and dealing

with the lingering effects of parental divorce. The social learning theory explains some effects

parental divorce can have on individuals, as parental relationships serve as early examples of

how social relationships are structured (Lee, 2007). This paper specifically inspected how

parental divorce affects individuals and how the social learning theory impacts an individual’s

thoughts toward divorce and future relationships.

Social Learning Theory

As divorce becomes more common within families, it is vital to understand the effect this

can have on individuals who grow up and witness this occurring to their parents. Past literature

has shed some light on this issue and its impact on future generations. As children grow and

develop, they take in information from the surrounding environment to better understand the

world around them and how they should act. This includes parental relationships, which children

observe during childhood/adolescence (Lee, 2019). Once observed, children then utilize the

information (interaction skills and behaviors) they have gathered from those parental

relationships to guide their behaviors regarding future relationships. However, if parental divorce

occurs, this can cause a rift in this dynamic, with children then observing an unhealthy

relationship (Lee, 2019). Through this lens, parental divorce could negatively affect individuals

if not addressed or known.

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

4

The social learning theory is present throughout psychology and is utilized in different

forms of therapy to not just predict individuals’ behaviors but also to improve relationships in

general. The social learning theory is based on the idea that relationships will improve when

positive interpersonal behaviors are supported and negative behaviors are punished (Johnson &

Bradbury, 2015). Over time, this perspective has been combined with different interventions to

help individuals improve their relationships with others through therapy, whether that be married

couples, family members, or friends (Johnson & Bradbury, 2015). As explained, the social

learning theory not only describes how children learn from the relationship between their parents

but also can explain how a couple could improve their relationship to build a positive

relationship that their children can observe.

Past research has found evidence to support the social learning perspective in relation to

parental divorce and the quality of romantic relationships for children (Lee, 2007). A study by

Lee in 2007 found that relationships between a parent and child can be predictive of the quality

of the child’s future relationships, more significantly for daughters’ relationships. In the study,

daughters’ relationships with their parents were shown to predict the quality of their future

romantic relationships. However, this same finding was not supported for males of parental

divorce, with relationships between sons and their parents not being as significantly predictive of

the quality of the son’s future romantic relationships (Lee, 2007).

In a study by Vonbergen in 2012, eight licensed clinical social workers were interviewed

to understand the effects that parental divorce has on individuals. One of the social workers’

main findings was the modeling that individuals received while growing up. Although each

social worker had a slightly different approach to this topic, each social worker emphasized the

importance of the need to address modeling that individuals received from their parents while

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

5

growing up and how some might be affected by divorce. As mentioned in the article, some

participants had to receive new forms of modeling due to parental divorce in the past and lacking

positive role models while they were growing up. According to the social learning theory,

modeling is necessary for developing children to make sense of the world, so learning to observe

models in their life is essential (Vonbergen, 2012). However, some children grow up without

positive modeling due to divorce and the loss of parental figures in a household.

The studies conducted by Vonbergen (2012) and Lee (2007) both explain how the Social

Learning Theory work in principle as well as data to show that the concepts contained in this

theory do guide the behaviors of children as they grow up observing the world. By understanding

the effect that the Social Learning Theory has on the development of individuals, the ideas

within this theory can be utilized in therapy to help people improve and change their

interpersonal behaviors and the relationships they have with people.

Role of Parental Divorce

One effect of parental divorce that literature has explored is how parental divorce can

influence individuals to view relationships differently. A study by Nelson (2009) found that

individuals with divorced parents felt more anxious regarding commitment to romantic

relationships and less satisfaction in marriage. It was also found that parental divorce also

influenced individuals to be less involved in relationships that they were currently in. However,

when individuals did have committed relationships, cohabitation rates of non-married couples

were higher than rates of married couples living together (Nelson, 2009). As shown, this study

collected data to support the stance that parental divorce does correlate with more hesitancy

towards marriage and commitment among individuals who grow up observing parental divorce.

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

6

Similar to the previous study, Booth et al. (1984) also analyzed parental divorce’s effects

on individuals, specifically the courtship of offspring in later romantic relationships. However,

contradictory to Nelson (2009), this study found that parental divorce was predictive of higher

levels of courtship in offspring. This differed from the study conducted by Nelson (2009)

because it showed increased levels of involvement for individuals who had experienced parental

divorce. To explain this finding, the study stated that a possible reason behind the increased

levels of courtship in offspring could be the motivation that the offspring had not to replicate

their parents' relationship, which resulted in divorce (Booth et al., 1984). For this reason, the

participants may have put more effort into courtship to ensure that their romantic relationship

would not end in divorce like their parents.

Past research contains mixed results regarding this topic, with some studies finding that

people have positive reactions toward their parents’ divorce, contradicting the results of studies

such as Nelson (2009). Amato and Booth (1991) found that individuals of divorced parents had

positive attitudes toward divorce in general compared to individuals from parents who remained

married. However, as explained by Amato and Booth this happened because the participants

reported that they favored divorce compared to the continuation of conflict between their parents.

This was also similar for individuals who reported their parents’ marriage to be filled with

unhappiness. These participants also held positive attitudes toward the alternative of divorce if

needed in their own life (Amato & Booth, 1991). Furthermore, the study by Amato and Booth

also reported that individuals from divorced parents were more likely to experience divorce

within their own romantic relationships than individuals from married parents.

Building on the findings in the previous study, another study found similar results

indicating that individuals who witnessed more marital violence and conflict would be more

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

7

likely to accept divorce as a favorable outcome in the long run (Mitchell et al., 2021). The study

by Mitchell et al. (2021) explained how individuals who had experienced parental divorce that

consisted of violence/conflict were more favorable of divorce because the conflict itself was

reason enough for the divorce to occur. This finding might be different for individuals who

experienced parental divorce that was calmer or more respectful because there would not be as

much reason for the divorce to occur. Furthermore, because the children did not have to

experience as much conflict, they might not be able to comprehend why their parents decided to

divorce (Mitchell et al., 2021).

As shown, people have mixed views and reactions toward divorce after experiencing or

witnessing their parents go through a divorce. Studies such as Nelson (2009) found that parental

divorce increased hesitancy toward future romantic relationships. Other studies, such as Amato

and Booth (1991) and Mitchell et al. (2021), found contradictory data showing that some people

had positive views towards divorce. The results of these studies could be explained to support the

fact that individuals might have higher anxiety levels after parental divorce. This could be the

case because many of the participants from the studies by Amato and Booth (1991) and Mitchell

et al. (2021) reported favoring divorce as an alternative to marital violence or conflict, which

demonstrates their desire to lower familial conflict that might worry them within their parents’

marriage.

Hypothesis 1: Individuals with divorced parents will have higher anxiety levels regarding their

own romantic relationships compared to individuals with married parents.

Participants with divorced vs married parents: The participant will self-report this variable.

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

8

Anxiety: Low anxiety will be a score of 0 - 21 on the Beck Anxiety Inventory. Moderate anxiety

will be a score of 22 - 35 on the Beck Anxiety Inventory. Potentially concerning levels of anxiety

will be a score of 36 or higher on the Beck Anxiety Inventory.

Gender and Romantic Relationships

Due to gender norms and expectations, gender is a factor that could impact individuals

regarding parental divorce. Gender expectations and differences in lived experiences between the

genders could explain why some people feel differently about given topics, parental divorce

being one. Despite this, a study by Brewer (2010) found that gender does not seem to cause a

significant difference in how much depression men versus women feel after experiencing

parental divorce. However, the rate of depression was markedly high, with about 60% of men

and women from families with divorced parents suffering from depression later in life. In this

instance, gender did not seem to impact how much depression men versus women felt, with both

genders feeling similar levels of depression (Brewer, 2010).

Attachment styles between individuals within a relationship can be another way of

analyzing gender differences and how they react due to parental divorce. A study by Sprecher et

al. in 1998 gathered data on this topic from 1,000 participants, with about 250 participants

having divorced parents. There existed no significant difference in attachment styles for males

with divorced parents and married parents (Sprecher et al., 1998). However, there was a

significant difference in attachment styles between women with divorced parents and women

with married parents. Women with married parents were more likely to have a secure attachment

style than those with divorced parents, who were more likely to have an avoidant attachment

style (Sprecher et al., 1998). This is relevant because attachment styles can influence how much

anxiety an individual feels toward a relationship. If women who experience parental divorce are

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

9

more likely to have avoidant attachment styles, this may cause them more anxiety with such

relationships. This could then translate into anxiety towards their romantic relationships.

Aggression levels between females and males in romantic relationships and friends have

also been researched. Although not a study concerning divorce, Goldstein (2011) found that

participants felt more aggression towards their romantic relationship partners than friends. This

was explained due to the increased importance that was put on companionship and intimacy

needs within romantic relationships compared to relationships with friends, which can strain the

relationship and cause aggression when not met (Goldstein, 2011). Additionally, when looking

further into romantic relationships, it was found that females reported higher levels of aggression

compared to males regarding romantic relationships. Goldstein discussed possible causes of this,

including the possibility that females might report more aggression because they notice social

transgressions more from their romantic partner, resulting in aggressive feelings (Goldstein,

2011).

Looking at romantic relationships without parental divorce being explicitly studied,

Muetzelfeld et al. (2020) found that couples who had high levels of attachment insecurity

reported these levels due to two causes: problems in communication and distress resulting from

family-of-origin and financial issues (Muetzelfeld et al., 2020). Specifically, females felt higher

levels of attachment insecurity due to distress from family-of-origin, whereas males felt higher

levels of attachment insecurity due to financial conflicts. This is interesting to note because the

distress from family-of-origin that the females reported could be connected to issues such as

parental divorce or separation.

As shown, gender can impact some aspects of an individual (attachment styles and

aggression levels) while not affecting other elements of a person (depression levels). There

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

10

appears to be a lack of research that analyzes how gender affects the amount of anxiety

individuals feel towards romantic relationships, specifically after observing parental divorce.

Due to this, anxiety levels in females and males after parental divorce will be an area of research

within this paper.

Hypothesis 2: Women with divorced parents will experience higher anxiety levels regarding their

own romantic relationships compared to men with divorced parents.

Gender of participant: The participant will self-report this variable.

Anxiety: Low anxiety will be a score of 0 - 21 on the Beck Anxiety Inventory. Moderate anxiety

will be a score of 22 - 35 on the Beck Anxiety Inventory. Potentially concerning levels of anxiety

will be a score of 36 or higher on the Beck Anxiety Inventory.

Parent-Child Relationships

Gender is also a factor to consider when it comes to the effect of parental divorce and the

types of relationships that are fostered between children and parents after divorce has occurred.

A study by Cooney found that it was less likely for both male and female children to live with

their father compared to their mother after the divorce, even if the family did not have to undergo

custody battles. This led to decreased contact between fathers and their children, most

significantly between fathers and their sons (Cooney, 1994). The reduced contact between

fathers and children after parental divorce is essential to acknowledge, especially regarding

custody battles and the reality that fathers might face in these situations.

Taking a closer look at relationships between fathers and children, Kalmijn conducted a

study in 2013 to analyze relationships that children had with their fathers following parental

divorce. This study analyzed the variables of contact, support, and quality of relationships

between individuals and their fathers. After collecting data, Kalmjin (2013) found that contact,

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

11

support, and quality of relationships between individuals and their fathers after parental divorce

were significantly more negative than the variables between individuals and their mothers.

Although the specific gender of the children was not analyzed, it supports previous findings that

children generally have stronger relationships with their mothers than fathers after parental

divorce occurs (Kalmjin, 2013).

Adding to the research about parent-child relationships, a study by White et al. (1985)

found that daughters and sons of married couples reported equal attachment to fathers after

divorce, so long as the father remained the custodial parent after the divorce. However, they

found that the reported parent-child attachment rates for noncustodial mothers and fathers were

significantly lower than for married parents. Furthermore, it was reported that attachment levels

between children and their noncustodial mothers were higher than those between children and

their noncustodial fathers. This demonstrates that the gender of a parent can affect parent-child

relationship closeness (White et al., 1985). This information shows the effect of divorce and

custody of children on parent-child relationships, supporting the stance that divorce can

negatively affect the children’s relationship with their parents.

Relationships between individuals and their parents after parental divorce are

complicated due to custodial situations and the addition of stepparents. Ivanova and Kalmjin

conducted a study in 2020 that found that participants from divorced parents had lower closeness

levels with biological fathers who had gotten divorced compared to stepfathers. Despite the

additional frequency of involvement or co-residence of birth fathers, this gap in closeness levels

between children and their biological fathers versus children and their stepfathers remained

(Ivanova & Kalmjin, 2020).

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

12

These studies demonstrate the impact that divorce can have on familial relationships,

including how custody of a child can affect the levels of closeness and quality of relationships

between children and their mothers and fathers. Although this past research sheds light on

parent-child relationships, there is one aspect of parent-child relationships that still needs more

analysis: the relationship between the two genders of children and the reported quality of their

relationship with their fathers following parental divorce.

Hypothesis 3: Daughters will report higher quality relationships with custodial or non-custodial

fathers after parental divorce compared to quality relationship levels between sons and

their custodial or non-custodial fathers after parental divorce.

Gender of participant: The participant will self-report this variable.

Quality of relationship: Higher scores on the Barrett-Lennard Relationship Inventory will be

representative of higher quality of relationships, while lower scores will be representative of

lower quality of relationships.

Reactions Towards Parental Divorce

The gender of an individual is another area to study regarding how people react to

parental divorce and its outcomes. Research has found that following recent parental

divorce/separation, higher levels of hyperactivity were found in sons compared to daughters

when reported by their mothers (Mitchell et al., 2021). This was a significant finding, with more

than double the number of boys than girls being within the borderline/abnormal range of

hyperactivity (Mitchell et al., 2021). This means that after experiencing parental divorce, boys

are more likely than girls to externalize their behaviors, whether that be positive or negative.

Although attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is more commonly diagnosed in men than

women, this is still an interesting finding.

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

13

Brewer (2010) conducted an additional study to analyze individuals’ reactions to parental

divorce, looking this time at depression levels reported by daughters and sons. This study utilized

the Carroll Depression Scale-Revised (CDS-R) to measure depression symptoms among

participants. After collecting data, Brewer (2010) found that an equal number of men and women

(60.6 % men and 60.0 % women) reported feeling symptoms of depression following parental

divorce. From this study alone, depression levels did not vary much between men and women

(Brewer, 2010).

One study by Block et al. in 1986 looked at children’s behaviors prior to parental divorce

and the differences in how boys versus girls behaved. The data from this study gave an

interesting insight into how children behaved before parental divorce when conflict and parental

issues were arising, eventually leading to the divorce. It was found that prior to parental divorce,

boys’ behavior was best characterized as actions fueled by impulse and aggression (Block et al.,

1986). On the other hand, girls' behavior was best described as less affected by environmental

stressors and more reflective of their parent's stress (Block et al., 1986). Block et al. stated that

the data collected was similar to reported data on the behaviors of children post-divorce. Taken

from the data, boys were shown to be more affected emotionally and physically leading up to

parental divorce compared to girls.

Looking specifically at boys’ and girls’ emotional reactions to stress without the study

being related explicitly to parental divorce can also give an insight into how gender can affect

differences in responses. One study analyzed this topic and found that female adolescents

reported higher levels of anger, depressive symptoms, and irritation within the last week

compared to male adolescents (Sigfusdottir & Silver, 2009). They also had higher levels of anger

outbursts. One reason to explain this could be that the female adolescents also reported

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

14

experiencing more negative life events during the study, including parental separation, losing a

friend, or an accident (Sigfusdottir & Silver, 2009).

Despite the results from Sigfusdottir and Silver (2009), most studies have collected data

demonstrating that boys tend to be more affected emotionally by parental divorce compared to

girls during and after divorce. Both Block et al. (1986) and Mitchell et al. (2021) also found that

boys were more likely to externalize their emotions when experiencing parental divorce than

girls.

Hypothesis 4: Males will experience higher anxiety rates towards their parents’ divorce

compared to females.

Gender of participant: The participant will self-report this variable.

Anxiety: Low anxiety will be a score of 0 - 21 on the Beck Anxiety Inventory. Moderate anxiety

will be a score of 22 - 35 on the Beck Anxiety Inventory. Potentially concerning levels of anxiety

will be a score of 36 or higher on the Beck Anxiety Inventory.

Method

Participants

One hundred and one undergraduate students from Chapman University were randomly

selected from the undergraduate psychology participant pool to participate in this study. Before

analyzing the data, fifteen participants were taken out of the survey. Eight of these participants

were taken out at the end due to not completing the survey fully and the seven other participants

were taken out because they did not pass the validity check that was put into the survey. Of the

remaining eighty-five participants, there were 7 males (8%) and 77 females (91%). One

individual did not report what their gender was. The mean age was 19.4 (s.d. = 2.2) years with a

range of 18 to 37 years. The race/ethnic breakdown was as follows:

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

15

• 53 (62.4%) self-identified as White/European American

• 25 (29.4%) self-identified as Hispanic/Latino

• 3 (3.5%) self-identified as Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

• 1 (1.2%) self-identified as Black/African American

• 14 (16.5%) self-identified as other races not listed

• 2 (2.4%) preferred not to answer

Measures

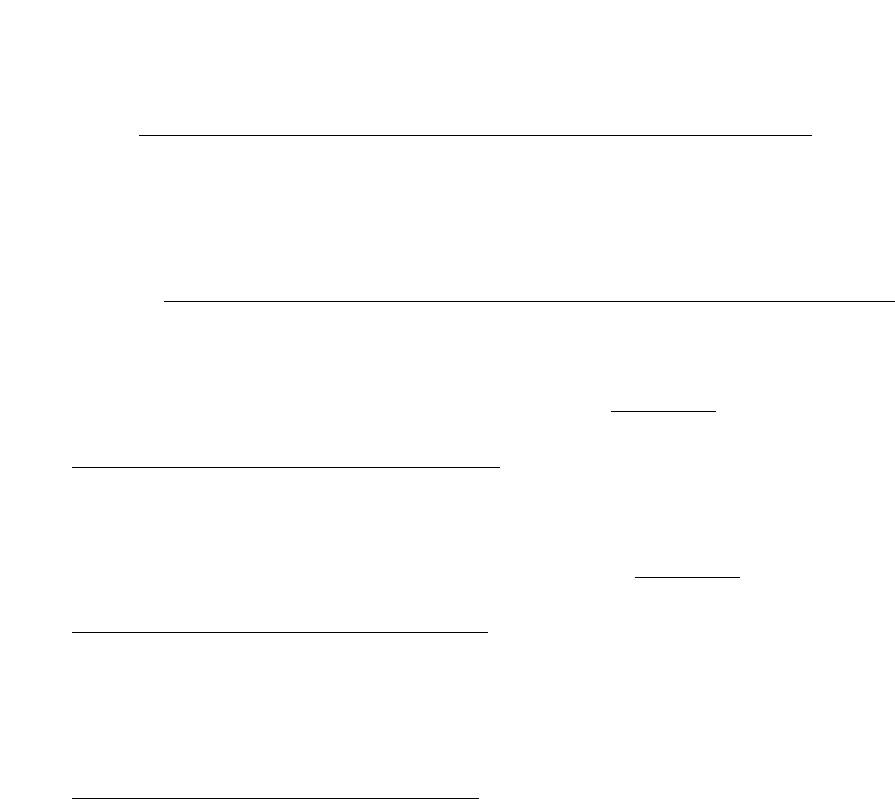

This study used the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Beck et al., 1988) and the Barrett-

Lennard Relationship Inventory: Form DW-64 (BLRI) (Barrett-Lennard, 2014). The Beck

Anxiety Inventory (BAI) was utilized to measure anxiety levels of the participants. The BAI was

created by Beck et al. (1988) and has a mean score of 15.75; however, a score above 36 indicates

potentially concerning levels of anxiety. The test-retest reliability was found to be 0.75 and the

validity of the survey is 0.78 (Beck et al., 1988). The survey is 21 questions long and is estimated

to take 10 minutes or less to complete. The survey uses a Likert-type response format. Examples

of statements in the survey include:

- I have been bothered by numbness or tingling

- I have been bothered by feeling hot

- I have been bothered by wobbliness in legs

Response categories for each statement include 0 = “Not at all”, 1 = “Mildly but it didn’t bother

me much”, 2 = “Moderately – it wasn’t pleasant at times”, and 3 = “Severely – it bothered me a

lot”. The complete Beck Anxiety Inventory survey is in Appendix A.

In this study, low anxiety is operationally defined as a score between 0-21 on the Beck

Anxiety scale. Moderate anxiety is operationally defined as a score between 22-35 on the Beck

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

16

Anxiety scale. Lastly, potentially concerning levels of anxiety is operationally defined as a score

between 36 and above on the Beck Anxiety Inventory.

For statistical purposes of the survey, the response categories were altered to be 1 = “Not at

all”, 2 = “Mildly but it didn’t bother me much”, 3 = “Moderately – it wasn’t pleasant at times”,

and 4 = “Severely – it bothered me a lot”. The new range of the survey was from 21 to 84. After

making this change to the response categories, low anxiety was operationally defined as a score

between 21-42 on the Beck Anxiety scale. Moderate anxiety was operationally defined as a score

between 43-56 and potentially concerning levels of anxiety was operationally defined as a score

of 57 or more on the Beck Anxiety Inventory.

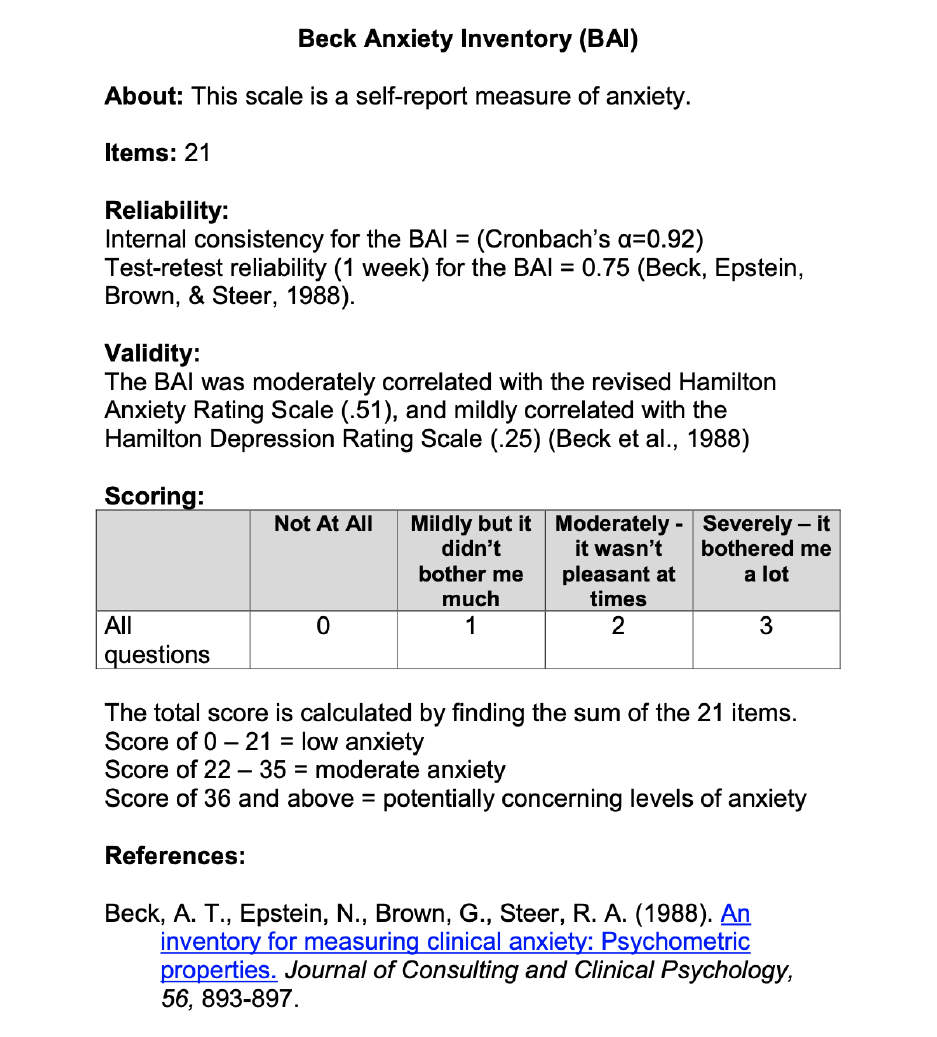

The Barrett-Lennard Relationship Inventory: Form DW-64 (BLRI) (Barrett-Lennard,

2014) measured the qualities of a participant’s relationship (empathy, regard, and congruence)

with another individual (their father). The survey has a range of -192 to 192, with higher scores

indicating higher quality of relationship. The test-retest reliability of the survey is 0.90 and the

predictive validity of the survey is 0.65 (Ganley, 1989). The survey is 64 questions long and is

estimated to take 25 minutes to complete. Examples of statements in the survey include:

- We respect each other as people.

- We feel at ease together.

- I feel that we put on a role or act with one another.

The survey uses a Likert-type response format (-3 to +3) with a “-3” representing “No, I strongly

feel that it is not true” and “+3” representing “Yes, I strongly feel that it is true”. The complete

Barrett-Lennard Relationship Inventory Survey is in Appendix B.

The response format was changed for this survey for statistical purposes. The survey used

an updated Likert-type response format (1 – 6) with “1” representing “Yes, I strongly feel that it

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

17

is true” to “6” representing “No, I strongly feel that it is not true”. The new range for the survey

was 0 to 384.

Procedure

Participants were recruited from the psychology participant pool (SONA). Once logged

into the SONA system, the participants were able to choose to take this survey from a variety of

other surveys online. There were no other recruitment procedures. After they chose to partake in

this survey online, the participants were told to read the informed consent carefully and to

provide their electronic signature before starting the study. The consent form stated that the study

was confidential and that the participants would remain anonymous throughout the study. It also

stated that the study posed no more than minimal risk to the participants and that no

compensation would be given to the participants. Following the consent form, the participants

were asked if they wished to participate in the survey and if they were 18 years of age or older. If

they answered yes, then they would be allowed to proceed to the survey questions and if they

answered no then they would not be allowed to complete the survey.

To begin, the participants were asked if their biological parents remained married with

each other until the present, or if their biological parents had been separated or divorced in the

past (self-reported variable). The participants were also asked other sociodemographic questions

such as their gender, sexual preferences, and their race/ethnicity (self-reported variables).

Participants were then asked to fill out the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Beck et al., 1988) to

measure the anxiety levels of participants regarding how they felt about their parents’ marriage

or separation/divorce. Following this, participants were asked to fill out the Barrett-Lennard

Relationship Inventory: Form DW-64 (BLRI) (Barrett-Lennard, 2014) to measure the qualities of

a participant’s relationship (empathy, regard, and congruence) with their father. They were then

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

18

asked to fill out the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Beck et al., 1988) again to measure the

anxiety levels of participants regarding how they felt towards their own future romantic

relationships.

Results

Hypothesis 1 stated that individuals with divorced parents would have higher anxiety

levels regarding their own romantic relationships compared to individuals with married parents.

A t-test was utilized to examine the differences between the divorced parents’ group and the

married parents’ group on a measure of anxiety. The possible range on the anxiety measure was

21-84. A score of 21-42 on the Beck Anxiety Inventory would be classified as low anxiety, while

a score of 43-56 would be classified as moderate anxiety. Potentially concerning levels of

anxiety would be a score of 57 or higher on the Beck Anxiety Inventory. The obtained range was

21-62. The mean score on the anxiety measure for the divorced parents’ group was 31.3 (SD =

12.6), whereas the married parents’ group scored an average of 27.2 (SD = 8.3). There was not a

significant difference between the divorced parents’ group and married parents’ group in terms

of score on the anxiety measure, t(70) = -1.4, p = .08. Thus hypothesis 1 was not supported.

According to hypothesis 2, women with divorced parents would experience higher

anxiety levels regarding their own romantic relationships compared to men with divorced

parents. A t-test was used to examine the differences between women with divorced parents and

men with divorced parents on a measure of anxiety. The possible range on the anxiety measure

was 21-84. A score of 21-42 on the Beck Anxiety Inventory would be classified as low anxiety,

while a score of 43-56 would be classified as moderate anxiety. Potentially concerning levels of

anxiety would be a score of 57 or higher on the Beck Anxiety Inventory. The obtained range was

21-62. The mean score on the anxiety measure for women with divorced parents was 30.8 (SD =

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

19

13.1), whereas men with divorced parents scored an average of 37.0. No standard deviation

could be found as only one male participant reported having divorced parents. There was not a

significant difference between women with divorced parents and men with divorced parents in

terms of score on the anxiety measure, t(10) = .5, p = .331. Thus hypothesis 2 was not supported.

Hypothesis 3 stated that daughters would report higher quality relationships with

custodial or non-custodial fathers after parental divorce compared to quality of relationship

levels between sons and their custodial or non-custodial fathers after parental divorce. A t-test

was run to examine the differences between women and men on a measure of quality of

relationship. The possible range on the quality of relationship measure was 0-384, with higher

scores on the quality of relationship measure being representative of lower quality of

relationships. The obtained range was 95-309. The mean score on the quality of relationship

measure for women was 205.0 (SD = 64.9), whereas men scored an average of 284.0. No

standard deviation could be found as only one male participant reported having divorced parents.

There was not a significant difference between women and men in terms of reported quality of

relationship, t(10) = 1.2, p = .135. Thus hypothesis 3 was not supported.

Lastly, hypothesis 4 stated that males would experience higher anxiety rates towards their

parents’ divorce compared to females. A t-test was utilized to examine the differences between

men with divorced parents and women with divorced parents on a measure of anxiety. The

possible range on the anxiety measure was 21-84. A score of 21-42 on the Beck Anxiety

Inventory would be classified as low anxiety, while a score of 43-56 would be classified as

moderate anxiety. Potentially concerning levels of anxiety would be a score of 57 or higher on

the Beck Anxiety Inventory. The obtained range was 21-72. The mean score on the anxiety

measure for men with divorced parents was 72.0 (SD = NA), whereas women with divorced

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

20

parents scored an average of 35.9 (SD = 15.2). There was a significant difference between the

men with divorced parents and women with divorced parents in terms of score on the anxiety

measure, t(10) = 2.3, p = .023. However, although statistically significant, the single male

participant did not allow for the conclusion to be made that the hypothesis was supported.

Discussion

With the national percentage of divorce increasing, it is important to look at the

consequences that divorce can have. This study aimed to look at the effects that divorce can have

on children by asking college-aged participants from Chapman University to reflect on their

parents’ divorce. A sample of eighty-five participants was ultimately analyzed to test four

hypotheses that attempted to look at variables such as anxiety, gender, parental divorce, and

quality of relationship. After running four t-tests, it was found that all four of the hypotheses

were not supported by the data. Evidence from the survey found that participants with married

parents and participants with divorced parents did not report statistically significant differences

in anxiety levels towards their own romantic relationships (hypothesis 1). There was also no

statistically significant difference between anxiety levels from women versus men with divorced

parents regarding how they felt about their romantic relationships (hypothesis 2). Hypothesis 3,

which stated that females would report higher quality relationships with fathers after parental

divorce compared to males was also not statistically significant. The fourth hypothesis was found

to be statistically significant, however, the single male participant did not allow for the

conclusion to be made that the hypothesis was supported. Out of the eighty-five participants,

only twelve reported having divorced parents, and only one identified as a male. Due to the small

number of individuals with divorced parents and the single male, it took significance away from

the results for this fourth hypothesis. These results could have occurred for a variety of reasons,

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

21

one reason being the small sample of participants that reported having divorced parents

compared to married parents and the small sample of males who took the survey. If the number

of males and individuals with divorced parents increased, this could contribute to more

significant results.

Despite not getting statistically significant results, some important connections to past

research need to be discussed in relation to this study. With respect to hypothesis 1, mean levels

of anxiety for how people felt about their romantic relationships for participants with divorced

parents was 31.3, while participants with married parents reported a mean score of 27.2. This

was similar to a study by Nelson (2009), who found that participants with divorced parents felt

more anxious about their romantic relationships compared to participants with married parents.

Past studies have found varying levels of different emotions in men and women after parental

divorce. In this current study, mean levels of anxiety for how people felt about their romantic

relationships for men was 37.0 and women 30.8. There was a limitation in this, however, as only

one male reported having divorced parents. Due to there not being a significant difference in

anxiety felt between men and women, it matched results present in a study by Brewer (2010).

Brewer (2010) found that there were no differences in levels of depression felt by men and

women after parental divorce. Results from the present study also show that males reported

higher quality of relationship with fathers than females did. This contradicts previous research

completed by Cooney (1994), who found that males reported lower quality of relationships with

fathers than females. The conflicting data between the two studies could be due to the current

study only having one male participant who reported about his quality of relationship with his

father, which does not provide enough evidence to be generalizable to a larger population of

men. Lastly, the study found that males reported feeling more anxious about their parents’

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

22

divorce compared to females, confirming past research that males are more emotionally affected

by parental divorce compared to females (Block et al., 1986; Mitchell et al., 2021).

There were multiple limitations present within this study that could have affected the

results and the generalizability of the research. One of the major limitations was the time

restriction that was placed on this study. This study had to be completed within two college

semesters, about 9 months. Additionally, the data collection itself had to be conducted over a

one-month span. Having a restriction on the time that could be spent on this study could have

limited the initial research done for the literature review, survey tools, and the creation of the

survey. It also limited the amount of data that was collected. If more time was permitted, then

more participants could have taken the survey and provided additional data. A second limitation

was the small sample size that the data was collected from. This was a big limitation of the study

as out of the eighty-five participants, only 12 participants reported having divorced parents, one

of these being a male participant. However, because a majority of the hypotheses for this study

were attempting to look at individuals with divorced parents, both male and female, this did not

provide a big enough sample to find statistically significant results. Furthermore, a third

limitation of the study was a lack of diversity. There existed a lack of diversity regarding

race/ethnicity within the sample as more than half of the participants identified as White, with

small percentages of participants identifying with other races/ethnicities. This means that the

results of the study are not generalizable and cannot be used to represent a multitude of

races/ethnicities within society. Diversity within the study was also limited regarding gender, as

the number of males in this study was much smaller than the number of females, with 7 males

(8%) to 77 females (91%). Similar to the limitation of race/ethnicity within this study, the results

also cannot be generalizable to the male population outside the study. Lastly, all the participants

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

23

who took the survey were students from Chapman University, adding to the lack of diversity as it

is only collecting data from college students who are a population of people that cannot represent

older or younger individuals in society. As shown, there were numerous limitations that existed

that could be improved upon in future research to get more accurate and statistically significant

results.

As research continues, determining future directions for studies is essential to advance

society’s understanding of topics such as divorce and the effects it can have on people. To

improve the research conducted within this study it would be beneficial to increase the sample

size in future studies. This would allow for the results of the study to be generalizable to more

people in society. Having more males and participants with divorced parents would also allow

the study to get a better understanding of what is happening to these groups of people, which the

current study failed to do. Collecting data from more races/ethnicities would also be helpful to

increase generalizability. Another area of this study that could be improved upon would be

reducing the number of questions within the survey to decrease respondent fatigue. Many

participants within the study did not answer all the possible questions, which could be due to the

length of the total survey. With several improvements and alterations to the original study, more

relevant and statistically significant data might be attainable.

Despite not finding statistically significant results in this study, it is important to have

intervention groups/organizations available to better support people who have experienced

parental divorce. Past studies should prompt therapy interventions to be accessible to any child

who experiences parental divorce, with therapy being offered at schools and daycares to prevent

the negative consequences of parental divorce.

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

24

References

Amato, P. R., & Booth, A. (1991). The consequences of divorce for attitudes toward divorce and

gender roles. Journal of Family Issues, 12, 306–322.

https://doi.org/10.1177/019251391012003004

Barrett-Lennard, G. T. (2014). Appendix 1: The relationship inventory forms and scoring

keys. The Relationship Inventory: A Complete Resource and Guide. Chichester, UK,

Wiley. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/9781118789070.app1

Beck, A. T., Epstein, N., Brown, G., & Steer, R. A. (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical

anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56,

893-897. https://www.jolietcenter.com/storage/app/media/beck-anxiety-inventory.pdf

Block, J. H., Block, J., & Gjerde, P. F. (1986). The personality of children prior to divorce: A

prospective study. Child Development, 57(4), 827–840. https://doi-

org.libproxy.chapman.edu/10.2307/1130360

Booth, A., Brinkerhoff, D. B., & White, L. K. (1984). The impact of parental divorce on

courtship. Journal of Marriage and Family, 46(1), 85–94. https://doi-

org.libproxy.chapman.edu/10.2307/351867

Branch-Harris, C., & Cox, A. (2015). The effects of parental divorce on young adults' attitudes

towards divorce. University Honors Program, 376.

https://core.ac.uk/download/60575574.pdf

Brewer, M. M. (2010). The effects of child gender and child age at the time of parental divorce

on the development of adult depression. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B:

The Sciences and Engineering, 71(6-B), 3917.

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

25

Cooney, T. M. (1994). Young adults' relations with parents: The influence of recent parental

divorce. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 56, 45-56. https://doi.org/10.2307/352700

Divorce statistics and facts: What affects divorce rates in the U.S.? (2022) Wilkinson &

Finkbeiner, LLP. Retrieved from https://www.wf-lawyers.com/divorce-statistics-and-

facts/#

Ganley, R. M. (1989). The Barrett-Lennard relationship inventory (BLRI): Current and potential

uses with family systems. Family Process, 28(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-

5300.1989.00107.x

Goldstein, S. E. (2011). Relational aggression in young adults’ friendships and romantic

relationships. Personal Relationships, 18(4), 645–656. https://doi-

org.libproxy.chapman.edu/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01329.x

Hartman, L. R., Magalhães, L., & Mandich, A. (2011). What does parental divorce or marital

separation mean for adolescents? A scoping review of North American literature. Journal

of Divorce & Remarriage, 52, 490–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/10502556.2011.609432

Ivanova, K., & Kalmijn, M. (2020). Parental involvement in youth and closeness to parents

during adulthood: Stepparents and biological parents. Journal of Family

Psychology, 34(7), 794–803. https://doi-org.libproxy.chapman.edu/10.1037/fam0000659

Johnson, M. D., & Bradbury, T. N. (2015). Contributions of social learning theory to the

promotion of healthy relationships: Asset or liability? Journal of Family Theory &

Review, 7(1), 13–27. https://doi-org.libproxy.chapman.edu/10.1111/jftr.12057

Kalmijn, M. (2013). Long-term effects of divorce on parent—child relationships: Within-family

comparisons of fathers and mothers. European Sociological Review, 29(5), 888–898.

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

26

Lee, S.A. (2019). Romantic relationships in young adulthood: Parental divorce, parent-child

relationships during adolescence, and gender. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(2),

411-423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-018-1284-0

Lee, S.A. (2007). Young adults committed romantic relationships: A longitudinal study on the

dynamics among parental divorce, relationships with mothers and fathers, and children's

committed romantic relationships. Retrieved from ProQuest Digital Dissertations.

https://www.proquest.com/docview/304895117?fromopenview=true&pq-

origsite=gscholar.

Mitchell, E. T., Whittaker, A. M., Raffaelli, M., & Hardesty, J. L. (2021). Child adjustment after

parental separation: Variations by gender, age, and maternal experiences of violence

during marriage. Journal of Family Violence, 36(8), 979–990.

Muetzelfeld, H., Megale, A., & Friedlander, M. L. (2020). Problematic domains of romantic

relationships as a function of attachment insecurity and gender. Australian and New

Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 41(1), 80–90.

Nelson, L. (2009). A review of literature on the impact of parental divorce on relationships in

adolescents. Retrieved from

https://minds.wisconsin.edu/bitstream/handle/1793/43271/2009nelsonl.pdf?sequence=1

Sigfusdottir, I.-D., & Silver, E. (2009). Emotional reactions to stress among adolescent boys and

girls: An examination of the mediating mechanisms proposed by general strain

theory. Youth & Society, 40(4), 571–590.

Sprecher, S., Cate, R., & Levin, L. (1998). Parental divorce and young adults’ beliefs about love.

Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 28, 107-120. https://doi.org/10.1300/J087v28n03_06

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

27

Vonbergen, A. (2012). Parental divorce: Social workers reflect on long-term effects for young

adults. Retrieved from Sophia, the St. Catherine University repository website:

https://sophia.stkate.edu/msw_papers/98

White, L. K., Brinkerhoff, D. B., & Booth, A. (1985). The effect of marital disruption on child's

attachment to parents. Journal of Family Issues, 6, 5-22. https://doi.org/10.1177/

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

28

Tables and Figures

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

29

Appendix A

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

30

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

31

Appendix B

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

32

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

33

EFFECT OF DIVORCE ON ANXIETY

34