Louisiana State University Louisiana State University

LSU Scholarly Repository LSU Scholarly Repository

LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School

2013

Physical self-concept and gender : the role of frame of reference Physical self-concept and gender : the role of frame of reference

and social comparison among adolescent females and social comparison among adolescent females

Emily Kristin Beasley

Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations

Part of the Kinesiology Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Beasley, Emily Kristin, "Physical self-concept and gender : the role of frame of reference and social

comparison among adolescent females" (2013).

LSU Doctoral Dissertations

. 1389.

https://repository.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1389

This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Scholarly Repository. It

has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU

Scholarly Repository. For more information, please contact[email protected].

PHYSICAL SELF-CONCEPT AND GENDER:

THE ROLE OF FRAME OF REFERENCE

AND

SOCIAL COMPARISON

AMONG ADOLESCENT FEMALES

A Dissertation

Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the

Louisiana State University

Agricultural and Mechanical College

in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

in

The School of Kinesiology

by

Emily K. Beasley

B.S. Mississippi State University, 2006

M.S. Mississippi University for Women, 2008

August 2013

ii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Throughout the years, there have been several people who have had a significant impact

on my education and career. Without them, this project would not have been possible. I would

first like to thank all of the students, teachers, and volunteers who were willing to lend a helping

hand throughout the data collection process. A special thanks to the members of my dissertation

committee: Dr. Alex Garn, who has spent countless hours revising and editing my work, Dr.

Melinda Solmon, a wonderful mentor and boss whom I admire, Dr. Birgitta Baker, who was

always willing to sneak away for coffee breaks and writing inspiration, and Dr. Laura Choate

and Dr. Catherine Champagne, who provided valuable insight and feedback. I am very fortunate

to have had the opportunity to work with such an outstanding group of professors and their

advice and guidance was invaluable.

There are two friends who I appreciate deeply, Dr. Laura Helen Marks and Dr. Jasmine

Hamilton. The two of you were there when I was in need of inspiration, motivation, or a good

laugh. I am extremely lucky to have a best friend and colleague in Dr. Ashley Samson, who has

been my partner in crime for the past four years, even when she was on the opposite side of the

country. You continue to remind me that I am powerful beyond measure. Also, to the extensive

list of friends who would never let me forget the importance of simply having a good time: Dr.

Steven McCullar, Molly Fisher, K-Lynn McKey, Bryce Dudley, Zach Montgomery, and Dr.

Lisa Johnson. Whether it was for a nice tailgate, a good run, afternoon refreshments, or an

inspirational quote, I knew one of you would be ready to accept the challenge.

I would like to extend a special thanks to my dear companions at Right Lead Equestrian

Center, most of all Frank, who was always there when I needed an escape. To Alex, who has

iii

been a constant companion throughout my entire education and a furry shoulder to cry on when I

needed it. He‟s hung around just to see me through.

I would also like to acknowledge the significant contribution my family has made to my

education. To Mom, you have always pushed me to excel in whatever it was I chose to do and

encouraged me to reach my full potential. To my Nanny, who has always been a positive light

and made me believe that I was one of a kind and the best in everything (regardless if that were

actually the case). To my brother Jace, who is a daily reminder of everything that is connected

and beautiful.

To my Daddy, who has made more sacrifices for me than I can even begin to count.

Without you, I would not be the woman I am today. You have taught me the value of hard work,

determination, and ingenuity. Not to mention how to ride a horse.

To Amon Craig, you have more patience than anyone I have ever known. Your unlimited

encouragement, love, and support have kept me going when I was ready to give up. The last

three years have been an incredible journey and I look forward to our future together.

Finally, I would like to acknowledge Mrs. Jackie Harrington. I can‟t think of another

person who has had a more profound impact on my perspective on life. Because of you I know

that pain is a good thing- it reminds us that we are still alive. You have shown me what it means

to give to others (and mean it), and I will never forget the role you played in the beginning of my

college career. Those late nights and weekends spent practicing in the gym are where it all

began, although I didn‟t see it at the time. You are the reason that I am a teacher and I can only

hope that one day I will be able to follow your example and pay it forward.

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................... ii

ABSTRACT .....................................................................................................................................v

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ..............................................................................................1

CHAPTER TWO: PHYSICAL SELF-CONCEPT AND FRAME OF REFERENCE FOR

GIRLS IN SAME-SEX PHYSICAL EDUCATION .......................................................................7

CHAPTER THREE: INVESTIGATING A BIG-FISH-LITTLE-POND EFFECT AND

MODERATING EFFECTS OF CLASS TYPE FOR GIRLS IN PHYSICAL

EDUCATION ....................................................................................................................37

CHAPTER FOUR: SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS ............................................................58

REFERENCES .............................................................................................................................65

APPENDIX

A: EXTENDED REVIEW OF LITERATURE ......................................................................75

B: STUDENT SURVEY ......................................................................................................120

C: FIELD OBSERVATION DATA COLLECTION FORM ..............................................122

D: INTERVIEW PROTOCOL .............................................................................................123

E: CHAPTER TWO EXTENDED RESULTS .....................................................................125

F: COPY OF IRB APPROVAL FORM ...............................................................................144

VITA ...........................................................................................................................................145

v

ABSTRACT

Quality physical education can positively influence students‟ emotional development,

specifically their perceptions of competence, self-esteem, and self-concept. Unfortunately, girls

often become less engaged and involved in physical education as they grow older and

consistently report lower physical self-concepts than males. Physical self-concept is associated

with multiple positive outcomes, yet there is only speculation addressing why females report

lower physical self-concepts than males in physical education. The overall purpose of this

dissertation was to investigate potential explanations for gender discrepancies in physical self-

concept among physical education students. One qualitative and one quantitative research study

was conducted to address this issue.

The purposes of the qualitative study were to capture female students‟ personal

interpretations of physical self-concept, frame of reference, and the physical education

environment. Results indicate that the girls enrolled in same-sex physical education classes

perceived the coed environment negatively and experienced pressure regarding physical ability

and appearance. Competition in physical education received significant attention and was

desirable only in appropriate levels and contexts. Results supported that the students used

multiple sources of information in physical self-concept development. Participants conformed to

traditional gender norms and viewed males as more aggressive and physically dominant than

females. In addition, all participants perceived same-sex physical education as a more desirable

setting.

The purposes of the quantitative study were to investigate a BFLPE and moderating

effects of class type among female students in physical education. It was hypothesized that: a)

vi

individual ability would positively predict sport self-concept and class-level ability; b) class-

level ability would negatively predict sport self-concept (also known as a BFLPE); and c) class

structure (e.g. same sex, coeducational) would moderate the BFLPE in physical education.

Results provided evidence that participants in both class types experienced a BFLPE. Class type

did not increase or decrease the BFLPE for these students, indicating that the girls in these coed

classes were not at an increased risk for experiencing negative consequences to their sport self-

concept as a result of a BFLPE.

Overall, results provide additional information of physical self-concept development

among adolescent females in physical education. Implications for practitioners and suggestions

for future research are included.

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION

Dramatic declines in physical activity levels and participation in physical education have

contributed to an increase in overweight and obesity for children and adolescents (Cumming et

al., 2011; United States Department of Health and Human Services [USDHHS], 2011). Regular

physical activity engagement in exercise settings such as physical education can benefit students

not only physically, but cognitively, emotionally, and socially as well (Bailey, 2009; USDHHS,

2011). Despite the benefits of physical activity, there is still a pressing need to motivate students

to participate in physical education classes. Unfortunately, students‟ enjoyment and positive

attitudes toward physical education decline during the transition from childhood to adolescence

(Subramaniam & Silverman, 2007). Physical self-concept, an individual‟s perception of himself

or herself within the physical domain (Marsh, 1990), is an intrinsic factor that can help explain

student engagement in physical activity both in and out of physical education (Beasley & Garn,

in press; Carlson, 1995; Welk & Joens-Matre, 2007). Positive physical self-concept is related to

physical activity participation and both adoption and adherence (Crocker et al., 2003; Cumming

et al., 2011; Dunton, Jamner, & Cooper, 2003; Marsh, Papaioannou, & Theodorakis, 2006) and a

multitude of other important outcomes such as increased happiness, intrinsic motivation, and

physical performance and decreased depression and anxiety (Craven & Marsh, 2008; Crocker,

Sabiston, Kowalski, McDonough, & Kowlaski, 2006; Schneider, Dunton, & Cooper, 2008).

Physical self-concept research has consistently identified gender differences across

multiple physical activity settings, including physical education, with females reporting lower

physical self-concept than males (Caglar, 2009; Hagger, Biddle, & Wang, 2005; Hagger at al.,

2010; Schmalz & Davison, 2006). In addition, as girls develop and mature, they tend to become

less physically active and report lower physical self-concepts than younger girls (Cumming et

2

al., 2012). There has been considerable speculation as to why girls report lower physical self-

concepts than males in physical education, and many have suggested that discrepancies in

physical self-concept scores are a result of traditional gender stereotypes in Western society

(Caglar, 2009; Crocker et al., 2003; Klomsten, Marsh, & Skaalvik, 2005; Schmalz & Davison,

2006). This is a likely explanation considering that schools are complex social environments

where gender stereotypes are reinforced and traditionally masculine subjects such as physical

education magnify the differences between males and females (Bain, 2009; Connell, 2008; Kirk,

2003; Penney & Evans, 2002). However, simply accrediting gender differences in physical self-

concept to gender stereotypes in physical education is likely a naive, inadequate explanation. The

complete understanding of this phenomenon is far more complex and there is a need for deeper

investigation of females‟ physical self-concept construction within the gendered environment of

physical education. It is likely that female students‟ social comparisons of ability and frame of

reference within the physical education setting play a role in their physical self-concept

development (Craven & Marsh, 2008; Marsh & Craven, 2002; Marsh et al., 2008b). The

gendered environment of physical education provides a complex setting to examine physical

self-concept construction and Marsh‟s (1990) theoretical framework offers a developmental and

multidimensional perspective to explore the physical self-concept development of adolescent

females in physical education.

Overview of Self-Concept and Physical Self-Concept

Self-concept is an individual‟s self-perception that is formed through his or her

interactions with and interpretations of the surrounding environment (Marsh, 1990; Marsh &

Shalveson, 1985). It can be differentiated from other constructs, has a multifaceted and

hierarchical structure, and undergoes developmental changes (Marsh, 1990; Marsh & Shalveson,

3

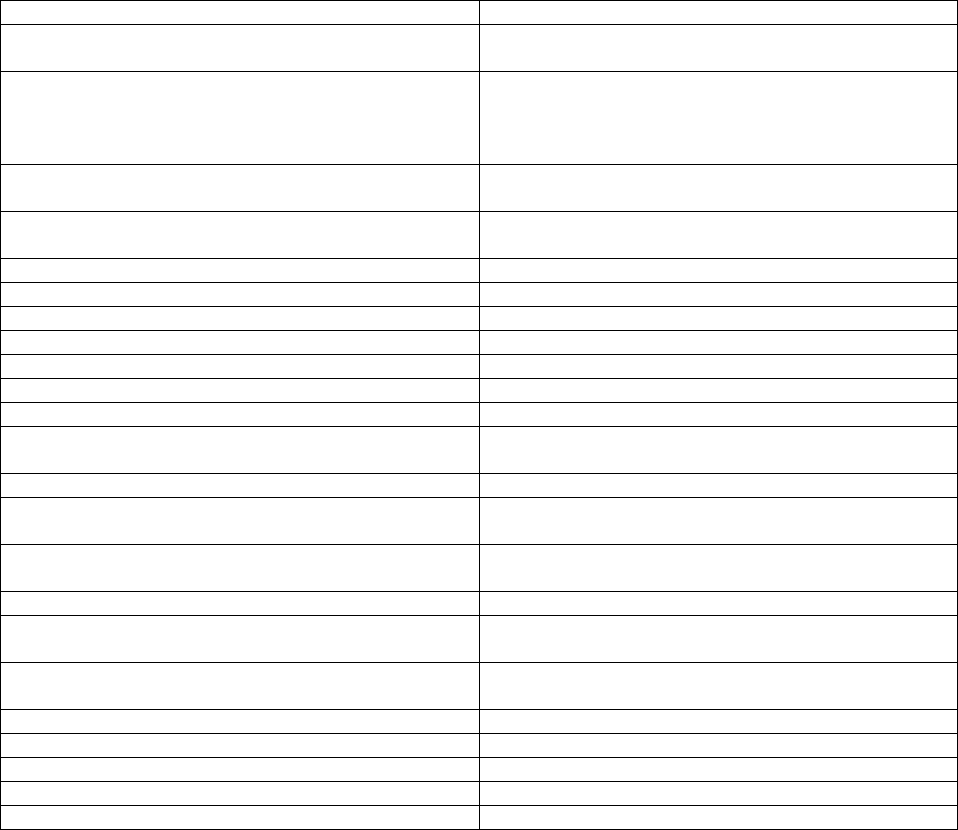

1985). In Marsh‟s (1990) model, self-esteem (global self-concept) is divided into academic and

nonacademic self-concepts. In the nonacademic domain, self-concept is further separated into

social, emotional, and physical self-concept sub-domains (See Figure 1.1). Consequently, each

sub-domain is considered to also have a multidimensional structure (Marsh, 1990; Marsh &

Craven, 2006; Marsh & Shalveson, 1985).

Figure 1.1. The Hierarchal Structure of Self-Concept and Physical Self-Concept.

Currently, there is substantial support for the multifaceted nature of self-concept and

although global self-concept is not insignificant, it is no longer considered a useful tool for

understanding the distinct dimensions of self-concept (Craven & Marsh, 2008; Marsh & Craven,

2006; Marsh & O‟Mara, 2008; Marsh, Trautwein, Ludtke, Koller, & Baumert, 2006). Therefore,

it is strongly suggested that researchers focus on the dimensions of self-concept most pertinent to

their field (Marsh, 1990, 2006; Marsh & O‟Mara, 2008; Marsh & Craven, 2006). For researchers

Global Self-

Concept

Academic

Nonacademic

Social Emotional Physical

Physical

Ability

Strength

Activity

Levels

Endurance

Sporting

Ability

Physical

Coordination

Flexibility

Physical

Appearance

Appearance

Body Fat

Health

4

in physical education, physical self-concept is the sub-domain most applicable to understanding

this construct within the complex physical and social environment of physical education (Craven

& Marsh, 2008; Marsh, 1990; Marsh & O‟Mara, 2008).

Physical self-concept refers to an individual‟s perception of himself or herself within the

physical domain and is separated into two specific categories: physical ability and physical

appearance (Marsh, 1990, 1996, 1999, 2002; Marsh & Craven, 2006; Marsh & Shalveson, 1985;

Peart, Marsh, & Richards, 2005). In physical education, physical self-concept maintains the

multidimensional structure that has been recognized in other physical settings (Dunton et al.,

2006; Gheris, Kress, & Swalm, 2010; Marsh, Hau, Sung, & Yu, 2007). Specifically, Marsh and

colleagues suggest that an individual‟s perception of his or her physical strength, body fat,

physical activity levels, endurance, sporting ability, physical coordination, physical health,

physical appearance, and physical flexibility all contribute to his or her overall physical self-

concept (See Figure 1.1) (Marsh, Richards, Johnson, Roche, & Treymayne,1994). There is

strong support that as children age, physical self-concept becomes more differentiated and

multidimensional (Marsh 1993; Marsh, Debus, & Bornholt, 2005; Marsh et al., 2007); indicating

that physical self-concept is also best studied from a developmental perspective (Marsh, 1993,

2002, 2006, Marsh, et al., 2007).

An individual‟s frame of reference plays an important role in the development of global

and physical self-concept (Marsh & Craven, 2002) and there is support for frame of reference

effects for physical self-concept in physical education (Gheris et al., 2010; Trautwein, Gerlach,

& Ludtke, 2008). The Internal/External Frame-of-Reference (I/E) Model provides a framework

for understanding the development of self-concept in relation to internal and external

comparisons (Craven & Marsh, 2006; Marsh, 1990; Marsh & Craven, 2002). For instance,

5

internal comparisons of ability within each domain can impact self-concept in other domains. A

student may have average math ability and above average physical ability and he or she will in

turn use this internal comparison of ability in two separate domains to construct self-concepts in

each area (Marsh & Craven, 2002; Marsh, Hey, Roche, & Perry; 1997). Students may also

compare current performances on a specific task with their own previous performances within

the physical domain (Gheris et al., 2010). As a result, the construction of a positive physical self-

concept is part of an internal self-evaluation process. In addition to these internal evaluations,

external comparisons, like social comparisons of ability, influence the development of physical

self-concept. As children grow older, external comparison increasingly plays a larger role in self-

concept development (Marsh, 2006; Marsh, Trautwein, Ludtke, & Koller, 2008) and the context

of physical education provides a complex environment to negotiate physical self-concept

construction. For instance, physical education classrooms often have children exhibiting skills in

a social setting and these public displays of ability provide an optimal scenario for students to

engage in external social comparisons of ability (Gheris et al., 2010; Trautwein et al., 2008).

In order to provide further explanation of social comparison effects on self-concept

development, Marsh and colleagues created the Big-Fish-Little-Pond Effect (BFLPE) framework

(Marsh et al., 2008b; Marsh & Craven, 2002; Marsh, Seaton, Trautwein, Ludtke, Hau, O‟Mara,

& Craven, 2008). The basic premise of the BFLPE is that students with high ability will have a

lower self-concept when surrounded by others with high average ability. Conversely, students

with average ability will have a higher self-concept when surrounded by others with low average

ability (Chanal, Marsh, Sarrazin, & Bois, 2005; Marsh, Seaton, et al., 2008). There is currently

limited support for the BFLPE for physical self-concept in physical education (Chanal et al.,

2005; Trautwein et al., 2008) and while preliminary evidence for the I/E Frame-of-Reference

6

Model and the BFLPE in physical education does exist, it is sparse and conclusions from this

research are limited.

Adolescent females in physical education tend to report lower physical self-concepts than

males, which is frequently attributed to gender stereotypes. However, a multidimensional and

developmental perspective of physical self-concept construction can provide insight into how

physical self-concept may be affected in the physical education environment. Physical education

is an ideal setting for internal comparisons of performance as well as social comparisons of

ability. Therefore, there is a substantial need for deeper investigation of how adolescent girls‟

frame of reference and the social environment of physical education influence the development

of a positive physical self-concept.

The purpose of this dissertation is to explore how adolescent females in physical

education perceive the physical education environment, their personal interpretations of physical

self-concept, and the role of social comparison in their physical self-concept development.

Chapter 2 examines how female students in physical education perceive internal and external

frames of reference and captures their personal interpretations of physical self-concept, frame of

reference, and the physical education environment. This study employed a phenomenological

framework that included extensive field observations and in-depth participant interviews with

female students enrolled in same-sex physical education classes. Chapter 3 used survey and

physical ability data to investigate a possible BFLPE for sport self-concept in a sample of

adolescent females enrolled in same-sex and coeducational physical education classes.

7

CHAPTER TWO: PHYSICAL SELF-CONCEPT AND FRAME OF REFERENCE

FOR GIRLS IN SAME-SEX PHYSICAL EDUCATION

Introduction

Past research has suggested that physical self-concept, an individual‟s perception of

himself or herself within the physical domain (Marsh, 1990, 2002), is a primary determinant of

adolescent girls‟ global self-concept (Beasley & Garn, in review; O‟Dea & Abraham, 1999). A

positive physical self-concept is associated with physical activity participation, skill

development, and motor learning in physical education (Guerin, Marsh, & Famose, 2004; Peart,

Marsh, & Richards, 2005) and physical education can aid in the development of positive physical

and global self-concept among young girls (Craven & Marsh, 2008; Daley & Buchanan, 1999;

Jones, Polman, & Peters, 2009). Physical self-concept researchers have consistently identified

gender differences, with females reporting lower physical self-concept than males across

multiple physical activity settings, including physical education (Caglar, 2009; Hagger, Biddle,

& Wang, 2005; O‟Dea & Abraham, 1999; Schmalz & Davison, 2006).

Although gender differences in physical self-concept are well documented, there is

currently only speculation as to why these differences are so distinct within physical education.

Many researchers attribute these gender discrepancies to Western society‟s gender stereotypes

(Asci, 2002; Klomsten, Marsh, & Skaalvik, 2005; Klomsten, Skaalvik, & Espenes, 2004;

Schmalz & Davison, 2006). While this seems to be a reasonable conclusion, simply attributing

gender differences in physical self-concept among physical education students to gender

stereotypes may not account for the complexity of this phenomenon. It is likely that gender

stereotypes in physical education and female students‟ frame of reference regarding their

physical capabilities and appearance are closely related to physical self-concept development.

8

Physical Self-Concept

According to Marsh‟s (1990) theoretical framework, self-concept has a multidimensional

and hierarchal structure. In this framework, self-esteem, identified as global self-concept, is

divided into academic and nonacademic self-concepts. In the nonacademic domain, self-concept

is further separated into social, emotional, and physical self-concept sub-domains. Physical self-

concept is a multidimensional facet of nonacademic self-concept (Craven & Marsh, 2008;

Marsh, 1990) and the two primary sub-domains of physical self-concept are physical ability and

physical appearance, which are further divided into nine separate sub-categories. More

specifically, Marsh and colleagues (Marsh, Richards, Johnson, Roche, & Treymayne,1994)

suggest that an individual‟s perception of his or her physical strength, body fat, physical activity

levels, endurance, sporting ability, physical coordination, physical health, physical appearance,

and physical flexibility all contribute to his or her overall physical self-concept (See Figure 2.1).

Self-concept is constructed in relation to the surrounding environment (Marsh, 1990; Marsh &

Shalveson, 1985), and the Internal/External Frame-of-Reference (I/E) Model (Marsh, 1986)

provides a valuable theoretical perspective to examine the development of these multiple facets

of physical self-concept in physical education.

Internal /External frame-of-reference model. Previous inquiry of self-concept

development within the academic domain has established that the construction of self-concept is

related to both internal and external factors (Marsh & Craven, 2002). Marsh‟s (1986)

Internal/External (I/E) Frame-of-Reference Model provides a theoretical framework for

understanding the development of self-concept in relation to internal and external comparisons

(Craven & Marsh, 2006; Marsh, 1990; Marsh & Craven, 2002). The I/E Frame-of-Reference

Model is based on the distinctiveness of and potential interactions between internal and external

9

frames of reference (Marsh & Yeung, 1998). Theorists‟ posit that individuals use: (a) internal

comparisons of ability (e.g. comparing current performances to past performances) in different

domains to construct self-concept within specific domains; and (b) external comparisons of

ability (e.g. comparing personal performance on a task to a peer‟s performance on the same task)

in order to construct domain-specific self-concepts (Craven & Marsh, 2006; Marsh & Craven,

2002).

Figure 2.1. The Hierarchal Structure of Self-Concept and Physical Self-Concept.

Since the original development of the model, Skaalvik and Skaalvik (2002) have

identified more specific internal and external frames of reference and sources of information

within school settings. The five sources of information identified for both frames of reference

are: (a) direct observations of achievement, (b) the teachers‟ responses and comments, (c)

responses and comments from classmates, (d) responses and comments from individuals outside

Global Self-

Concept

Academic

Nonacademic

Social Emotional Physical

Physical

Ability

Strength

Activity

Levels

Endurance

Sporting

Ability

Physical

Coordination

Flexibility

Physical

Appearance

Appearance

Body Fat

Health

10

the class, and (e) grades. For external comparisons, students may use school-average ability,

class-average ability, students within their class, or students outside of their class as frames of

reference. For instance, students may overhear the teacher complimenting another student‟s

achievement in a particular subject and use this external source of information to form his or her

respective domain-specific self-concept. Likewise, the frames of reference for internal

comparisons are focused on achievements in different school subjects at the same point in time,

in the same subject over an extended period of time, in different subjects with respective goals

and aspirations, and in different subjects with subsequent effort in each (Skaalvik & Skaalvik,

2002). Thus, a student may compare his or her grade in a particular subject to grades received in

the same subject in a previous year and use this internal comparison to construct his or her self-

concept in that area.

The I/E Frame-of-Reference Model is a robust framework that has demonstrated cross-

cultural generalizability within academic settings (Marsh & Yeung, 1998; Marsh, Kong, & Hau,

2001). According to a meta-analysis conducted by Moller and colleagues, this framework is

applicable across gender, age groups, cultures, and various achievement settings (Moller,

Pohlmann, Koller, & Marsh, 2009). Therefore, this model is well-suited for examination of the

role frame of reference may play in physical self-concept development in physical education.

Unfortunately, investigation of the I/E Frame-of-Reference Model in the physical domain is

extremely limited. Although incomplete, previous studies have begun to provide preliminary

support for frame of reference effects in the development of physical self-concept in physical

education (Gheris, Kress, & Swalm, 2010; Trautwein, Gerlach, & Ludtke, 2008). For example, it

has been documented that students often compare their current performance on a specific task

with their own previous performances (Gheris et al., 2010). In addition, Marsh (1993) reported

11

that social comparisons of running ability among students impacted their own self-perceptions in

the physical education class.

The context of physical education provides a complex setting to negotiate the

development of physical self-concept. For instance, PE classrooms often have children

exhibiting skills in social settings and such public displays of ability provide an optimal scenario

for external social comparisons (Gheris et al., 2010; Trautwein et al., 2008). It is likely that in

physical education, both internal and external frames of reference work in combination with one

another, and in relation to the different sources of information outlined by Skaalvik and Skaalvik

(2002). For instance, a physical educator may provide corrective feedback regarding a student‟s

performance of a particular skill, such as throwing (e.g. “Remember to turn your side to the

target.”). The student may perceive that he or she is exerting the same amount of effort to

execute the skill as if completing an exam in math. However, if feedback from the math teacher

is positive regarding his or her performance (e.g. “You did a great job on this exam!”), the

student may form negative internal perceptions of his or her ability in physical education and

physical self-concept may be negatively influenced. In a similar manner, a different student may

overhear the physical education teacher‟s corrective feedback regarding throwing and observe

his or her classmate working to correct a skill that he or she has already mastered. This student

may use this external comparison and evaluate himself or herself more positively, which would

have a positive impact on physical self-concept.

Given the above examples, it is reasonable to conclude that the I/E Frame-of-Reference

Model can be readily applied to a physical education setting. It is inferred that perceptions of

ability play a major role in physical self-concept development (Marsh et al., 2010), yet research

of frame of reference in physical education has centered on students‟ actual ability or utilized

12

only quantitative data without taking students‟ actual perceptions and interpretations of ability

into consideration (Chanal, Marsh, Sarrazin, & Bois, 2005; Trautwein et al., 2008). Considering

the lack of extant research in this area, there is a substantial need to examine students‟ physical

self-concepts and perceptions of the physical education environment from a qualitative

perspective. A deeper understanding of students‟ personal interpretations of physical self-

concept development in physical education can provide physical educators with valuable

information that could empower them to become more effective educators. A phenomenological

methodology provides a unique perspective that allows the researcher to become immersed in the

physical education experiences of participants and observe the environment firsthand. Therefore,

the purpose of this study was to provide in-depth descriptions of female students‟ personal

interpretations of physical self-concept, frame of reference, and the physical education

environment using a phenomenological approach

Methods

Qualitative Design

Considering the extensive role self-perceptions play in physical self-concept

development, this study employed a phenomenological methodology in order to closely examine

students‟ personal perceptions and views (van Manen, 2011). One advantage of using a

phenomenological approach is its ability to describe a phenomenon and how individuals interpret

this phenomenon (Patton, 2002). In addition, such methodology allows the researcher to become

immersed in the experiences of the study participants (van Manen, 1990, 2011). Consequently, in

this study, asking students to describe their experiences, perceptions, and feelings in-depth

provided deeper insights into their personal perceptions of frame of reference, the physical

education environment, and physical self-concept.

13

According to van Manen (1990, 2011), a phenomenological methodology involves three

primary data collection strategies: (a) observation, (b) field notes, and (c) interviewing. In a

phenomenological approach, the researcher plays an essential role and must integrate him or

herself into the participants‟ environment to gain an in-depth understanding of the phenomenon.

Through conducting detailed observations the researcher attempts to describe, explain, and

interpret participant experiences. In order to understand how individuals interpret events or

environments, the researcher must also observe these events and environments firsthand (Patton,

2002). This experience allows the researcher an additional viewpoint other than simply that of

the participant (van Manen, 1990, 2011). In a similar manner, researchers then conduct in-depth

interviews to gain insight into the participants‟ interpretations of the phenomenon (Patton, 2002).

Finally, throughout the entire process, the researcher attempts to describe and understand the

phenomena at hand through both writing and rewriting field notes and his or her personal

interpretations of the phenomenon (van Manen, 1990, 2011).

Participants

Participants in this study were ten female students (N= 10) enrolled in one ninth grade

(n=6) and one tenth grade (n=4) physical education class at a local all-girls private high school.

The girls reported their ethnicity as Caucasian (100%), with a mean age of 14.7 years (SD=.48).

All of the students were self-described as physically active and were involved in various

structured and informal physical activities outside of school (e.g. running, soccer, basketball,

bowling, etc.). In addition, all of the girls were consistently observed participating during the

physical education classes.

14

Setting

Classes took place across two consecutive semesters (spring and fall) and two

participants were enrolled in both classes. Classes were taught by one female certified physical

education teacher and met daily for 50 minute time periods. The physical education program at

the school was based on a multi-activity model and each class participated in at least three

physical education curricular units per semester. Field notes provided rich descriptions of several

of the units and the atmosphere of the class during each unit. Units included individual lifetime

activities such as badminton, archery, Pickleball, and fitness exercises. Team sport activities like

basketball and softball were also offered. In addition, nine weeks of the semester were spent in

health units where topics such as CPR and eating disorders were covered. All students were

required to dress out in school-issued uniforms (identical t-shirts and athletic shorts of their

choice) during physical education classes. Students were required to take two semester credits of

physical education before graduation and received a letter grade for the course. Grades were

based on participation, dressing out, and scores on written exams.

It is important to note that throughout the school there was an overwhelming sense that

all-girls schools are preferable to coed settings. This culture and belief that same-sex classes are

“better” was reinforced by both students and teachers, especially with regard to physical

education. Therefore, the overall perception that all-girls classes are significantly more beneficial

to female students than coed classes was taken into consideration when interpreting the results of

this study.

Role of the Researcher

All observations, field notes, and interviews were completed by one female researcher

who was familiar with the school, administration, and faculty. She had facilitated field teaching

15

experiences and observations at this school for physical education teacher education students

from a local university throughout the two years prior to data collection. She also accompanied

university students during observations and field teaching experiences. In addition, the

researcher was a former physical education teacher and viewed the physical education

environment from an educator‟s perspective. She became a fixture in the classes and throughout

the course of field observations and interviews, students would often ask their physical education

teacher about the researcher when she was not present. Therefore, participants in this study were

very comfortable with her and accustomed to her presence in their physical education classes. As

a result, participants were open and forthcoming throughout the data collection process. This

open relationship with both the participants and the teacher facilitated follow-up interviews and

discussion where the researcher was able to spend a significant amount of time discussing

emerging themes as a method to reduce researcher bias.

Procedures

Permission to conduct this study was granted by the University Institutional Review

Board. Students were provided with a full description of the study procedures prior to

participation and informed consent was collected from parents. Likewise, all participants were

required to submit a signed child assent form prior to participation. Participants first completed

questionnaires containing demographic questions and items evaluating physical self-concept.

Survey responses were used as selection criteria for interviews. In addition, participants were

observed during physical education classes.

Measures

Participants were selected for interviews based upon their responses to the global

physical self-concept scale (M=4.01, SD=1.54) of the PSDQ-S (Marsh et al., 2010) (See

16

Appendix B). Purposeful sampling took place in order to recruit students with a wide range of

scores on the PSDQ-S (1.00-5.67). Students (N=12) from both semesters (spring and fall) were

invited to participate in interviews, however, two of the invited students declined citing the time

commitment as a barrier to participation

PSDQ-S. The PSDQ-S (Marsh et al., 2010) is a psychometrically sound 40 item

instrument containing items from the PSDQ (Marsh, 1996) and it has good reliability, test-retest

stability over both short and long term, a well-defined factor structure that is invariant over

gender, and both convergent and discriminant validity (Marsh, 1997, 2002; Nigg, Norman,

Rossi, & Benisovich, 2001). The PSDQ-S is a valid and reliable measure with reliability

coefficients ranging from .84-.91 (Marsh et al., 2010). Items from the global physical subscale,

which require individuals to respond to the declarative statements 1) “Physically, I feel good

about myself”, 2) “Physically, I am happy with myself”, and 3) “I feel good about who I am

physically” on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 6 (very true), were used to

select participants for interviews.

Data Collection

Field Observations. Field observations (N=30) were conducted and each observation

lasted for the duration of one physical education class period (50 minutes). Observations spanned

across the spring (n=14) and fall (n=16) semesters. During observations, extensive field notes

were taken and the researcher provided detailed descriptions of the physical education

environment, social context, activities, students‟ interactions with one another, and interactions

with the teacher. Immediately following each observation, field notes were typed, analyzed, and

separated into the following categories: Class Description, Additional Notes, Perceptions and

Thoughts, and Further Questions (See Appendix C).

17

Interviews. A total of nineteen participant interviews (N=19) were completed. Each

interview lasted approximately 30 minutes (M= 30.16; SD=9.36) and was audio recorded.

Interviews took place before school, during lunch periods, or after school and were conducted in

an empty health classroom located in the school gymnasium. The majority of participants

completed two interviews; however, one student (Morgan) completed the interview protocol

during one session and declined to participate in a second interview. Participants responded to

questions such as: “What do you like/dislike about your physical education class?”, “How would

you describe your abilities in PE?”, and “How would you describe the atmosphere of your PE

class?”. In addition to the interview protocol (See Appendix D), discussion was prompted based

on events taking place in the physical education class (e.g. “Can you tell me more about what

you did in class today?”).

Data Analysis

Phenomenological themes are understood as “the structures of experience” (van Manen,

1990, p.79) and an integral component of a phenomenological research design is thematic

analysis. It is important that those who were engaged in the experience play a significant role and

provide personal insight during the coding process. Thus, field notes and interview transcriptions

were analyzed line-by-line by the primary researcher. Emerging themes identified during the

reflective process (van Manen, 2011) were then discussed with participants during follow-up

interviews. An inductive analysis approach was employed to identify categories, sub-themes, and

higher-order themes (Patton, 2002). Interviews, field notes, and member checks were used in

order to triangulate the data and reduce researcher bias. In addition, informal collaborative

reflection with a second researcher took place during revision of the initial themes (van Menen,

2011).

18

Results

Three major themes developed from data analysis: (a) Social Risk, (b) A Favorable

Competitive Environment, and (c) Points of Perception. Multiple aspects of Social Risk in

coeducational (coed) physical education were identified, specifically anxiety and perceived

pressures regarding physical ability and appearance. However, same-sex physical education was

perceived to negate these concerns and was viewed as a positive alternative. Competition was

frequently discussed in terms of A Favorable Competitive Environment. Overall, participants

enjoyed and valued competition but it was considered to be activity dependent, unpleasant in

certain circumstances, and desirable only in appropriate amounts. Finally, participants outlined

two Points of Perception, “firsthand accounts” and “external feedback”, which provided a basis

for physical self-concept development.

Social Risk

“Social Risk” was a major theme that emerged from data analysis. All participants

(100%) indicated that physical education created a social environment that was distinct from

other classes and some (60 %, 6/10) saw the social atmosphere as the most positive aspect of

physical education. However, the social environment was not always viewed positively. The

class structure, specifically a coed setting, was perceived to have potential negative social

consequences.

Appearance in coed classes. Participants addressed two primary “Social Risks” in coed

physical education; anxiety regarding appearance (50 %, 5/10) and physical ability (80%, 8/10).

Participants drew on past experiences and compared their current class to coed classes they

experienced during middle school. For example, Vanessa (all names are pseudonyms) (mid-

19

range physical self-concept) discussed how important appearance could be in coed physical

education when she said:

The girls would, before they go out to PE they would go and fix their hair and make sure

that nothing was wrong or whatever because of the guys. But here it‟s just like, you get

changed and then you go out and you don‟t really have to worry about if your hair is out

of place or if you haven‟t shaved or something like that. That really doesn‟t go against

you I guess. Just cause all-girls, like, some girls haven‟t shaved or whatever so you

don‟t have to worry about being criticized.

Dee (high physical self-concept) expressed similar feelings and mentioned that in an all-female

environment the girls didn‟t “worry as much about sweating”. Laura (mid-level physical self-

concept) said she tries harder in an all-girls class because “no one really cares about your

appearance” and she believed that in coed classes the girls “don‟t try as hard” and “they only

cared about their appearance”. The perceived pressure to appear a particular way in coed classes

was discussed by several participants. Beth (low physical self-concept) considered the coed

atmosphere to set different expectations and demands on girls with regard to appearance and

said, “I think the pressure would be higher in a coed school because there‟s guys everywhere and

you have to worry about what you look like and how skinny you are, and make-up and clothes,

stuff like that”. It is interesting to note that throughout the course of field observations, there

was never an instance when a student did not dress in the required physical education uniform

(school issued top and athletic shorts) and between two classes (n=46), only one student was ever

noted to wear visible make-up.

Ability in coed classes. Participants also discussed in detail perceived “Social Risk”

associated with ability in coed physical education. There is a substantial threat for students who

are considered to be less skilled in a coed class and according to Morgan (low physical self-

concept), the less skilled students are the girls. She stated, “I feel like guys have their own level

and girls have their own level of skills”. Alicia (high physical self-concept) articulated similar

20

feelings and said, “I think for coed you have more of the varied skill set… and I think there‟s big

differences in coed PE.” According to Amanda (mid-level physical self-concept), “some guys

have different abilities than girls” and boys are “more athletic”.

Even girls like Michelle (high physical self-concept), who consider themselves skilled,

may not have sufficient ability to succeed in a coed setting. She said, “I could always like, hang

ya know? Like up there, but maybe not in like, basketball. Because boys tend to overpower in

those kinds of sports.” The idea that boys overpower girls in coed physical education and take

control of the class was consistent among other participants. Dee said the boys would “be

playing hard and running fast so the girls didn‟t have time to reach it [the ball]”. She also

commented that the girls were “letting the guys do whatever they want” and “weren‟t

participating as much [as the boys]”. Amanda also discussed how girls‟ participation can be

negatively impacted in coed classes and said, “I feel like guys are more prone to exclude girls

cause they‟re like „Oh she can‟t do it, she can‟t do this, she can‟t do that‟.” Feelings of

inadequacy, awkwardness, and embarrassment regarding ability in a coed environment were

common threads for the girls in this study. Beth commented, “Guys would get mad if you didn‟t

win or do something right.” Heather (high physical self-concept) discussed how insufficient

knowledge and ability in physical education could be detrimental for girls and said:

With coed, the guys know how to play sports, so when you would ask a question, you

didn‟t want to seem stupid. In all-girls, most of the girls in my class don‟t really know all

the knick-knack rules of the sport, so you don‟t really feel like an outcast asking a

question.

Surprisingly, interview data suggested that in coed classes the some of the girls were not

only worried about a lack of ability, but also appearing to be overly skilled. According to

participants (30%, 3/10), there are negative consequences for girls who are “athletic” in coed

physical education. They appear to be “trying too hard” and are at risk for name calling. For

21

example, Dee expanded on this idea when she stated that there was “a really athletic, competitive

girl at my old school and they called her a man”. Heather had a similar experience and said,

“There was this one girl, everyone called her „the beast‟ because she was just amazing at

everything we did and she was better than some of the guys.” Morgan explained perceived

pressures regarding appearance and ability best and said, “Guys are supposed to be better and

manlier looking than girls are.” She also stated, “When guys are there you don't wanna look like,

not manly but, like you‟re better than they are and so you don't wanna try as hard.”

Field notes provided evidence of a wide range of skill levels in each class. However, the

students observed to be the most skilled were often cheered on by classmates and provided with

positive feedback. There were no instances reported or observed where high skilled students

experienced negative consequences regarding ability. Thus, all participants (100%) expressed

that same-sex physical education classes reduced these concerns. According to Beth, there are

advantages to an all-female environment because, “You‟re not as embarrassed to do different

things cause there are not guys watching you.” Heather had a similar attitude and commented,

“You don‟t have to feel embarrassed. Like, if you can‟t kick the ball across the gym, you don‟t

feel embarrassed, because girls don‟t always care about that kind of stuff.” Rebecca (low

physical self-concept) preferred an all-girls class because she felt less pressure to perform. She

said, “I don‟t have to be impressive. Stuff like that. And people don‟t have to impress me or

anybody else.” Beth liked her same-sex class better than coed classes because “they [the girls]

don‟t really care if you win or not”. These results suggest that unlike a coed setting where there

was perceived pressure to appear and perform a particular way, the all-girls environment is one

with no fear of negative consequences associated with not meeting unspoken expectations.

22

A Favorable Competitive Environment

The second theme that emerged from participant interviews was “A Favorable

Competitive Environment”. All participants (100%) discussed both positive and negative

feelings toward competition and the majority (80 %, 8/10) stated that they valued and enjoyed

competition in physical education. The majority of girls (80%, 8/10) also said competition was

appropriate for physical education and there was a consistent belief that it is an enjoyable tool to

become more active, involved, and skilled in certain circumstances. However, there was a

consistent theme that competition is activity dependent, unpleasant in a coed setting, and only

appropriate in certain amounts.

Activity dependent. Over half (75%, 6/8) of the participants who believed competition is

acceptable in a physical education environment said it was activity dependent. The three most

popular activities mentioned as favorites during interviews were archery (50%, 5/10), softball

(40%, 4/10), and Pickleball (40%, 4/10), and for each some degree of competition was involved.

The archery unit culminated with an individual tournament, during the softball unit the teacher

recorded team scores, and the Pickleball unit consisted of a partner tournament. Alicia described

softball as “kind of competitive” because the teacher kept score, but “people were more

competitive” when it came to Pickleball. The Pickleball tournament was frequently discussed

and was considered a popular activity throughout the school. Each year the school would hold

one tournament and overall winners received a t-shirt. Michelle agreed that competition was

heightened during the Pickleball tournament and stated, “It got really competitive.” Student

perceptions of competition during activities varied and competition levels often fluctuated

between units. Morgan addressed this variation in her class when she said, “They [the teachers]

23

teach everyone how to play sports and some are more competitive than others, but there‟s a

variety of different things.”

The physical education students at this school had the opportunity to participate in a

variety of activities over the course of the semester and throughout field observations it was

often noted that the atmosphere of the class would change depending on the activity. The most

evident shift was observed during the archery unit. The first half of the unit had been spent

practicing and the second half was devoted to individual competition. In the first lesson where

scores were recorded, an obvious transition in the atmosphere occurred. During practice rounds

the students were primarily concerned with socializing and conversation was often focused on

irrelevant topics (e.g. boys, music videos, movies). However, when the teacher began keeping

score, the focus of conversation shifted and was concentrated on topics related to the lesson such

as shooting, performance, and scorekeeping. Overall, the class appeared to become more

engaged in the activity. In contrast, there were several activities, such as the fitness unit, where

little to no competition was observed. Therefore, competition in this physical education class was

often activity dependent.

Unpleasant in coed settings. Participants also discussed how competition was

unpleasant in a coed setting. When asked to describe the negative aspects of competition

Amanda said, “Well I used to go to a coed school so it was a little bit more uncomfortable with

guys, but it‟s really not here cause you can kindof be yourself.” Another participant, Michelle,

described the differences between coed and same-sex classes and said, “It‟s a little different

because in coed PE it was more competitive, but in this one it‟s not as competitive cause

everyone‟s kindof laid back”.

24

Often participants (50%, 5/10) described males in physical education as “aggressive” or

“rough”. For example, when explaining why she believes boys and girls should participate in

activities separately Rebecca said, “Cause some boys and girls aren‟t the same. It‟s like you‟re

playing, such as a mouse playing a bear.” The fear of being overpowered or even injured when

participating in competitive physical activities with males was mentioned by Vanessa, who said

she would not want to play a sport with boys because “they get pretty aggressive if you‟re

playing on the same team”. She said in that situation she would opt out of the game and “let them

do all the work”. Throughout participant interviews, the idea that an all-girls physical education

class is a more positive setting for competition was frequently discussed. Morgan mentioned that

the all-girls environment was well-suited for competition because “you can be yourself really

and do what you want to do and be competitive”. Amanda, who described herself as “pretty

competitive”, also suggested that the environment of the class was a positive outlet for

competition and referred to it as a “safe environment to be able to play” and a “safe place to

interact.” Although the belief that competition in a coed physical education setting was

unpleasant and could be physically or emotionally damaging to girls was prevalent, for the girls

in this study same-sex physical education was a solution to their concerns.

Acceptable levels. Although the majority of girls (80%, 8/10) preferred competition and

felt their own physical education environment to be a safe and comfortable outlet for it, a large

percentage (60%, 6/10) discussed an acceptable level of competition. For example, although

Pickleball was often viewed in a positive light, Morgan offered another viewpoint when she said,

“Some people do get really, really, into it. I got like really into it too, and it‟s to the point to

where it‟s not fun cause you‟re just trying too hard.” Michelle also suggested that there is an

acceptable level of competition and commented, “If you don‟t have competition it‟s not really

25

that fun, but if you have too much competition then people get mad and it‟s just a lot a stupid

stuff going on.”

When describing the acceptable level of competition for physical education, participants

discussed negative aspects to either not having enough competition or being immersed in an

overly competitive environment. The physical education classes the participants were enrolled in

were described as “not really competitive”. For half of the participants (50%, 5/10), a lack of

competition was even perceived negatively and they expressed a desire for more competition. If

there appeared to be a lack of competition in particular sports (e.g. basketball or badminton) that

were intended to be competitive, the girls who were self-described to be “taking the game

seriously” expressed a sense of frustration. Participants mentioned that in basketball there were

other students who “really didn‟t care” or who were “lazy” and without competition they

couldn‟t “get a good game” and the games would be “so boring”. Overall, there was a general

theme that an appropriate level of competition was enjoyable when experienced in a safe and

positive environment.

Points of Perception

Finally, participants in this study identified firsthand accounts of achievement and

external feedback as “Points of Perception” related to physical self-concept development.

Firsthand accounts of others‟ achievements and their own individual accomplishments were

often identified by the girls as sources of comparison for multiple aspects of physical self-

concept. In addition, participants used external feedback from others in order to construct their

physical self-concepts.

Firsthand accounts of others. The majority of participants (80%, 8/10) discussed

multiple aspects of physical self-concept in relation to firsthand accounts of others‟ ability,

26

others‟ appearance, or their own performances. Field observations supported this finding. For

instance, the structure of the archery unit facilitated direct observations of classmates. Students

watched one another shoot and were often overheard cheering and making encouraging remarks

such as “good job” and “that was a good shot”. In one instance, a student told her group member

“good job” when she hit the target, yet later referred to herself as “terrible” when she missed her

own shot. She observed her peer hit the target and used this firsthand account of another‟s

performance to provide information regarding her own competence. Throughout the unit, it was

not uncommon to observe the students encouraging their classmates, yet often making degrading

comments regarding their own personal performances.

For some participants (40%, 4/10), the most common source for firsthand accounts of

physical ability were family members. The physical self-concept domains of flexibility, strength,

and sports ability were all described via firsthand accounts of family members‟ ability in these

areas. For example, both Beth and Amanda described themselves as “not as flexible” as their

sisters and Alicia evaluated her sports ability positively because her family is “really athletic”.

Although participants described themselves in relation to others in several of the physical self-

concept sub-domains, they frequently discussed their appearance in relation to that of friends

(20%, 2/10) and other girls in general (70%, 7/10). Morgan described her friends as the opposite

of herself when she said “My friends are just really tiny and they‟re not as tall as me.”

Field notes validated friends as a source of firsthand comparisons for appearance. During

a “Power Walk” lesson, two girls were observed comparing their stomachs and thighs and

pinching body fat on their midsections. Throughout the conversation, they were overheard

commenting “I‟m insecure in a swimsuit now”, “I need to lose a few pounds”, and “I need to get

back in shape”. When firsthand accounts of other girls in general were the primary sources of

27

information, comparisons were based on appearance, body shape, and body size. When asked to

describe her appearance Heather stated, “I would say that there are prettier girls and then there

are like…I‟m better looking than some girls.” Vanessa communicated similar feelings when

discussing various aspects of her own body, such as muscle definition, and commented that her

legs were “not as skinny as somebody else‟s”. She also expressed conflicting emotions related to

comparing herself to others who had different body shapes and sizes:

It can be bad for your…. I guess if you‟re looking at someone who is really skinny it

can be bad. Like, I really wanna look like her but I can‟t, just because how my body is

and how I‟m built, because I play soccer and all these other sports so much.

Morgan also talked about comparing herself to others and the idea of being “skinny”.

She said, “It‟s just, everyone is skinny I guess and you fit in more [if you are also

skinny]”. Another participant, Beth, was very honest regarding her firsthand accounts of others‟

appearance when she admitted, “I do look at the super-skinny and wish that I had that body.” It

is interesting to note that even when discussing endurance, Rebecca referred back to her body

shape and size and compared herself to other girls when she said, “Well, I‟m not one of those

really, really, skinny girls that can run, you know.” For the girls in this study, firsthand accounts

of others‟ physical appearance were the most frequently discussed sources of information.

Firsthand accounts of ability. All participants (100%) discussed firsthand accounts of

personal performance as “Points of Perception” for physical ability. For example, Michelle

expressed her feelings of coordination when she commented, “Coordination, I have pretty good

hand and feet coordination, like soccer, but there are a couple of things, like Pickleball, that I‟m

not good at.” All participants (100%) discussed flexibility in relation to firsthand accounts of

their own personal achievements. They made comments such as “I can only do a left split” or “I

can‟t touch my toes”. Participants also used firsthand accounts of personal performance when

comparing their academic and physical abilities. For example, Dee compared her achievements

28

in the physical domain to her academic abilities and said, “Well, I don‟t really exercise that much

so I wouldn‟t say I‟m really an athlete, but I mean, I‟m really good at math.”

External feedback. The second “Point of Perception” for participants in this study (50%,

5/10) was external feedback, specifically feedback from family members (20%, 2/10), coaches

(20%, 2/10), and friends (10%, 1/10). For instance, Vanessa said she knows how to describe her

abilities in soccer “by what my parents tell me”. Beth discussed comments from her friends when

asked about her appearance and said, “Friends tell me I‟m pretty and stuff. I mean, I don‟t really

agree with them.” Although it was not discussed during participant interviews, field observations

provided additional evidence that comments from others may be a source of information in the

physical education environment. Throughout the archery unit the girls consistently provided

positive feedback to one another regarding their performances. For example, one was overheard

saying “Becky is a pro at this” and later in the same lesson Becky told her group “I‟m finally

good at something”. Comments and responses regarding performance were not limited to verbal

feedback. During the badminton tournament, one partner group was consistently observed giving

each other high-fives when they scored a point. In addition, the teacher was often noted to

provide positive performance, corrective, and nonverbal feedback to students. Therefore,

although participants may not have been aware of it, they were often receiving feedback from

their peers and the teacher.

Discussion

This study examined adolescent females‟ physical self-concept from a phenomenological

perspective. Results indicate that female students in same-sex physical education classes may

perceive coed classes as places where they are at risk for emotional and physical harm.

Participants in this study discussed perceived pressures regarding both physical ability and

29

appearance in coed physical education. Results also highlight the role of competition in physical

education and how it impacts the class atmosphere. Participants complied with traditional gender

expectations and perceived males as aggressive, rough, and dangerous during competitive

activities. All participants viewed same-sex classes as a solution to their concerns regarding

physical ability, physical appearance, and competition in physical education. In addition, results

indicate that female physical education students use multiple sources of information to construct

their own physical self-perceptions of ability and appearance.

Participants in this study indicated a significant perceived social risk associated with coed

physical education, specifically concerns with regard to their appearance. These results are not

surprising considering the role of the body in physical education and the girls‟ perceptions that

they were often “being watched” by the boys during their coed classes. For example, physical

education often requires students to put their bodies on display and use them as a means of

demonstrating knowledge and skill in the physical domain (Azzarito & Solmon, 2006, 2009;

Larsson, Fagrell, & Redelius, 2009). In addition, students are typically expected to wear a

school-issued uniform, which was identified as a negative aspect of coed physical education,

perhaps because it can be uncomfortable or show certain parts of the body. In physical education

students may be required to wear shorts that expose their legs and if the uniform is ill-fitting, it

can emphasize feminine aspects of the body such as the breasts, hips, and waist. As girls

progress through adolescence, they often report increased levels of body dissatisfaction,

specifically with their hips, thighs, and waist (Rosenblum & Lewis, 1999) and if students are

uncomfortable in their uniforms these feeling may be amplified. Participants indicated that the

coed setting was a site where “guys are watching you” and expressed significant concern

regarding the presentation of their bodies in coed classes. Their concern was perhaps a result of

30

perceived male observation and increased feelings of discontent with feminine-typed body parts

(Azzarito & Solmon, 2006; Lawler & Nixon, 2011; Rosenblum & Lewis, 1999). Anxiety was

directed toward how the body was perceived in coed physical education and centered on

traditionally stereotypical attributes of femininity such as wearing make-up, having a nice-

looking hairstyle, or having shaved legs. Participants also expressed concern with appearing less

feminine, which included sweating during physical activity. Therefore, for girls like the ones in

this study who may feel watched by boys in their classes (Flintoff & Scranton, 2001; Webb,

McCaughtry, & McDonald, 2004), public displays of the body in combination with perceptions

of male observation in physical education can create negative feelings of anxiety and pressure.

These results hold many implications for practitioners. The internalization of appearance

ideals is associated with increased body dissatisfaction among adolescent girls (Lawler & Nixon,

2011) and appearance is an important sub-domain of physical self-concept (Marsh et al., 1994).

Therefore, increased anxiety regarding how the body is presented, how it meets appearance

ideals, and how it is perceived by others (i.e. male classmates) in coed physical education could

potentially negatively impact female students‟ physical self-concepts. The environment of the

coed class can sometimes create an increased awareness of the body and encourage conformity

to gendered body ideals for young girls. Teachers should be aware that female students may feel

as if they are being watched by male classmates and keep this in mind when asking students to

perform skills in front of the class or participate in activities that put the body on display in front

of others. Teachers should also consider how physical education uniforms can create unease and

anxiety for some students. For example, some girls may be uncomfortable wearing shorts if they

feel like they need to shave their legs. Physical educators can focus on creating an environment

31

where students feel comfortable, safe, and accepted to counteract female students‟ perceptions of

surveillance and feelings of unease resulting from gendered body expectations in coed classes.

Participants also identified negative consequences associated with possessing either too

much or not enough skill in coed physical education. Consistent with previous research, there

were negative social consequences such as name calling, harassment, and exclusion from

activities, associated with the girls‟ physical ability (Cockburn & Clarke, 2002; Hills & Croston,

2012). For example, participants indicated that they may be at risk of being called a “man” or

“beast‟ if they were considered to be “athletic” or would even be excluded from activities

entirely. These results are consistent with previous research stating that girls who are viewed as

“athletic” or are high-skilled in physical activity and sport are at risk for having their sexuality

questioned and may be called names like “tomboy”, “butch”, or “lesbian” (Clarke, 2002; Gorely,

Holroyd, & Kirk, 2003). In their coed classes, the girls in this study were attempting to balance

displays of skillfulness with feminine and masculine expectations. Girls tend to value skillfulness

and have a desire to appear strong and competent in physical activities (Azzarito, 2010; Lee,

2009), yet a desire to avoid displays of masculinity in physical education is not uncommon for

girls (Azzarito & Solmon, 2009), perhaps due to the perceived social cost of demonstrating

athleticism.

In contrast, when girls in coed physical education don‟t possess or demonstrate adequate

skill, they are often excluded from activities. Coed classes frequently participate in male-

stereotyped sports (Brown & Rich, 2002; Gorely et al., 2003) that require students to perform

masculine or feminine traits and girls may either choose not to participate or allow the high-

skilled males to dominate during these activities. For example, according to one participant, in a

masculine activity like basketball, students who demonstrate conventionally masculine

32

characteristics such as aggressiveness, speed, and power will be more successful, and these

students are typically the males in the class As Michelle indicated, girls who do not possess these

traits may consider themselves to be unskilled in physical education, which can negatively

impact their physical self-concepts. In addition, if these girls are using an external frame of

reference to evaluate their physical abilities, they will likely perceive themselves as inadequately

skilled.

Competition in physical education was also a key theme identified in this study. In a coed

setting, competition was perceived negatively and influenced girls‟ participation in activities

during class. These results are consistent with previous research indicating that girls in coed

classes are less active than boys (McKenzie, Prochaska, Sallis, & Lamaster, 2004). Participants

mentioned “not being on the same level as boys” in physical education and expressed a fear of

physical harm when competition was involved and girls played alongside or against boys. The

girls reflected that males tended to dominate during competitive activities like basketball and

displayed “rough” or “aggressive” behaviors. A male-model of physical education that includes

traditionally masculine and competitive activities and reinforces a dominant gender order is often

common in coed settings (Kirk, 2002, 2003). For males, such an opportunity to demonstrate their

skill, assertiveness, and masculinity during these competitive activities translates into physical

and social capital in the physical education environment. In the traditionally masculine culture of

coed physical education, teachers often provide male-stereotyped activities which value

aggressiveness, pain tolerance, and strength (Brown & Rich, 2002; Kirk, 2002, 2003). For girls

like the ones in this study, activities that are often dominated by the males in their classes and

encourage these traditionally masculine characteristics can create fear and anxiety. Although

teachers may not necessarily provide activities that involve physical contact, they should

33

consider physical closeness and competition when making curricular choices. For example,

participants often discussed basketball as a male-dominated contact sport that boys and girls

should participate in separately. Participation in such activities creates unease for girls regarding

their skill level and their physical or emotional safety. If teachers desire to implement

competitive activities in their classes, they should consider less traditional alternatives, like

ultimate Frisbee, that are not gender stereotyped. Modifying equipment (e.g. a Frisbee instead of

a basketball) and rules (e.g. everyone must touch the Frisbee before the team scores) allows the

teacher to create a more inclusive environment that will promote gender equity. In addition, these

modifications can create balance for a wide range of skillfulness in the class and produce a more

welcoming atmosphere for all students, regardless of skill level.

While all of the participants in this study preferred same-sex physical education and

identified it as a positive alternative to coed classes, it is important to note that the culture of the

school strongly advocated for an all-girls environment. However, the environment and

atmosphere of the girls‟ previous coed physical education classes may have also contributed to

their preferences for all-girls physical education. For instance, unfortunately teachers often

acknowledge male dominance in their classes as something that is expected and may

consequently avoid challenging traditional stereotypes or favor boys over girls (Chalabaev,

Trouilloud, & Jussim, 2009; Chepyator-Thomas & Ennis, 1997; Larsson et al., 2009). Students

and teachers are both aware of the gender order in physical education and generally enforce

dominant gender stereotypes associated with hegemonic masculinity (Brown & Rich, 2002;

Kirk, 2003; Larsson et al., 2009).Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that conformity to these