Footwork

in

Ancient

Greek

Swordsmanship

BRIAN F. COOK

Keeper,

Greek

and Roman

Antiquities,

The British

Museum

IN

HONOR OF MY

OLD

friend and

colleague

Helmut

Nickel,

I

should

like

to offer some

speculations

in

an

area where

his interest

in

arms

and armor

overlaps

mine

in

Greek and Roman

art,

in

particular

to

ex-

plore

the

possibility

that evidence

for

one

aspect

of

ancient

Greek

swordsmanship

can be found

in

Greek

sculpture

and

vase-painting.

Such an

exploration

can

only

be

tentative

in

the absence

of

supporting

evi-

dence

from

ancient

literary

sources,

especially

in the

period

around

500

B.C. Such

literary

evidence

as

does exist comes

from

later

periods

and deals

mainly

with tactics and

the

movement of

troops

in

forma-

tion,

of

concern to

the

ancient

equivalent

of

Clause-

witz

rather

than the

drill-sergeant.'

Detailed evi-

dence for basic drill-movements is

totally

absent

from the

literary

record

at all

periods.2

The

evidence

in

Xenophon

for

spear-drill

in

the

fourth

century

B.C. has been treated

in detail

by

J.

K.

Anderson,

who

warns that

in

trying

to reconstruct

ancient arms

drill,

it

is safer

"to use works of art

mainly

to

provide

illustrations of the ancient

texts,

while

admitting

that

there must

have been

several

movements for which no

literary

evidence has sur-

vived."3

Anderson

follows

his own

principle

by

using

illustrations in ancient art to

flesh

out

Xenophon's

description

of

spear-drill

with commands

given

by

trumpet-calls.4 Although

Anderson

concludes

that

training

in

ancient drill was restricted to a few

simple

movements,

he

concedes

that

they

were not necessar-

ily

limited to

those

for which

literary

evidence

sur-

vives. He even

accepts

that "the

repetition

of

certain

poses

in

works of art

raises

the

interesting

possibility

that

the

artists,

or their

models,

had

been

regularly

taught

the

movements

represented."5

The

specific example

cited

by

Anderson

of

sword-

movements

represented

so

often in works of art that

it

seems reasonable to

accept

them as

representations

of a

standard

action from

real

swordsmanship

is the

so-called

"Harmodios

blow" studied

by

Shefton,

who

coined the

useful term

by

which it

is now

fairly gen-

erally

known.6

This is a

slashing

movement

named

for

the action

of

Harmodios in the

marble

statuary

group

of

the

Tyrant-slayers

best known from

a Ro-

man

copy

in

Naples.7

The

moment most

frequently

represented

is

the

point

of stillness when the

sword-

hand has

been raised

head-high

with the

sword

pointing

backward over the

shoulder

in

readiness for

a downward

slash.

The blow

may

be delivered

either

forehand

(Figure

1)

or

backhand

(Figure

2).8

Philip

Lancaster,

of

the

Department

of

Edged

Weapons

at

the Tower

of

London,

who

kindly

gave

advice on

some

practical

aspects

of

swordsmanship,

pointed

out that

this

movement

would be

hazardous

under

normal

combat

conditions:

not

only

is

there some

danger

that it

would

put

a

swordsman

off

balance,

but

the

action

would also

leave the

sword-arm

unpro-

tected and

vulnerable. B. B.

Shefton

had

already

noted

that the

sword

when raised

could not

be

used

for

parrying,

and

that in

close

combat

the blow

therefore

required

careful

timing.9

It would

have

been

particularly

dangerous

for a

Greek

hoplite

in

leaving

the

armpit

exposed

above the

edge

of

the

cuirass.'0

A

further

disadvantage

of

the Harmodios

blow is

that it

was

less effective

than a

thrust

against

a

well-equipped

opponent:

it would

probably

have

been

resisted

even

by

a

padded

linen

corselet,

which

would

have

been

vulnerable to a

thrust,

and

would

certainly

have

been ineffective

against

a

metal cui-

rass."1

In

combat,

then,

the Harmodios

blow can

only

have

been

a

desperate

measure,

employed

when

the

vulnerability

it

imposed

was

outweighed by

a

greater

danger.

There

is

evidence for this in

both

literature

and

art.

The

problem

arises when

a

swordsman

faces

57

?

The

Metropolitan

Museum

of

Art

1989

METROPOLITAN

MUSEUM

JOURNAL

24

The

notes

for

this article

begin

on

page

62.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve, and extend access to

Metropolitan Museum Journal

www.jstor.org

®

1.

The forehand

"Harmodios

blow."

Drawing

of

an At-

tic

red-figured

hydria,

460-450

B.C. The

Metropol-

itan

Museum of

Art,

Fletcher

Fund,

1925, 25.28

(drawing:

Lindsley

F.

Hall)

the

longer weapon

of a

spearman:

the classic

solution

was that of

Hector,

who

cut

off the end of

Ajax's

spear

with

his

sword.'2

This is

precisely

the aim of

the Greek

in

Figure

2:

so

great

is his

danger

from the

Amazon's

spear

that he

must

attempt

to cut

its

wooden

shaft,

even at the risk

of

exposing

his whole

body

to

attack,

since he

must

swing

back his shield

to

maintain his balance.'s

A

safer use

of the Harmodios

blow,

as

pointed

out

by

Shefton,

was to deliver a

"butcher's

blow" to

a

fallen

opponent.14

Indeed,

the blow

could

only

be

used

safely

when

the

opponent

was

not in a

position,

or not

suitably

armed,

to strike

back.

The unfortu-

nate centaur in

Figure

3

has

no

weapon

for

a coun-

terstroke

and

only

a cushion

to ward

off an overhead

blow,

here from

a battle-ax

rather

than

from a

sword.'5

The

principle

of the Harmodios

blow still

applies:

an

overhead

blow

by

sword

or

ax

normally

leaves

the striker vulnerable.

Amphytrion

may

also

safely

use the Harmodios

blow

(Figure

i),

since

it is

aimed

not

at

an

armed warrior but

at

the

snakes

that

2.

The backhand Harmodios blow

used

against

a

spear.

Detail of an Attic

red-figured

squat

lekythos,

ca.

420

B.C.

The

Metropolitan

Museum

of

Art,

Rog-

ers

Fund,

1931,

31.11.13

have attacked the

infant Herakles. Here

too,

no

doubt,

there was an element

of

desperation.

Finding

no

examples

of the use of the Harmodios

blow

before the

closing

years

of the sixth

century

B.C.,'6

Shefton connected it with the

introduction of

the

spatulate

sword,

a more versatile

weapon

than

the

straight-edged

sword,

which is most effective

in

an

underhand

stabbing

or

thrusting

movement.17

It

is

around the same time

that warriors

began

to be

represented

in

Attic

red-figure

in a stance

that,

al-

though

it soon

became

conventional,

may

reflect

the

kind of

simple

drill-movement

for which no

literary

evidence

survives.

The movement

is in fact so

simple

that no

specific

comment was made

by

ancient

au-

thors:

like

so

many

minor details

of

life,

it was too

familiar at the time to call for

explanation.

The stance is

simple

enough

and

may

be observed

in

conjunction

with

the

Harmodios blow

in

the

rep-

resentations

already

discussed:

one foot is

simply

placed

in

advance of the other.

This is

not

merely

a

walking posture,

for,

as Borthwick has

pointed

out,'8

58

right-handed

swordsmen

commonly

advance

the

left

leg

and left arm

simultaneously,

as

in

Figure

4,

which

shows

a swordsman

using

a

straight-sided

sword

for

a conventional

upward

thrust

against

an

Amazon.19

In

what

may

be called

the "attack"

posture,

the for-

ward

leg

is bent

at the knee while

the other

leg

is

straight.20

Should the need arise to evade

an

oppo-

nent's

counterblow,

it is

possible

to

move the

body

back into

the "defense"

posture

without even

moving

the

feet,

simply

by

straightening

the

forward

leg

and,

if

necessary,

bending

the other.

The

Amazon

in

Fig-

ure

4

has

straightened

her

forward

right

leg

and has

bent her left.

The

painter

has even

shown her

left

foot

turning

away

to

produce

a

posture

that

is

scarcely

possible physically.

It was

presumably

in-

tended to

convey

a continuous

action,

beginning

with

a backward movement into the

defense

posture

and

freeing

herself

from

her

opponent's grip,

to be

fol-

lowed

(at

least

in

intent)

with

flight.

The

frequency

with which these

postures appear

in scenes

of combat

in

Greek

vase-painting suggests

that

they

represent

a

standard

drill-movement,

so

familiar as

not to re-

quire

comment

in

the

literary

sources.

Familiar

though

it

was,

it must at some

stage

have

been

learned. The Athenians did

not

provide

"train-

ing

in the art of war at

public

expense,"

at

least

not

for

adults;21

indeed

they

seem

to have taken an

ama-

teurish

pride

in

being

unlike the

Spartans

in

this

respect, although

they

were

expected

to

keep

them-

selves

physically

fit

for

warfare

by

regular

exercise.22

It

is

generally

assumed

that basic drill

was

taught

to

ephebes during

their

two-year

period

of

military

train-

ing,

undertaken

at the

age

of

eighteen.23

In Plato's

ideal

state,

the

military training

of

youths

was

to in-

clude

fighting

in

armor-hoplomachia

(translated

by

Anderson as

"fencing

with

hoplite weapons")24-and

it

seems reasonable

that this would

have included ele-

mentary

drill as

a

basis

for concerted

action

in the

field,

at

least

if modern

military experience

can be

accepted

as a substitute

for the nonexistent

ancient

literary

sources.25

Private

training

in

hoplomachia

seems

to have been

available

in

Athens,

at least

from the later fifth cen-

tury,

for the

discussion

of

courage

in Plato's Laches

begins

with a

demonstration

of the art

by

a

profes-

sional

instructor.26 The Greek term

for such

an in-

structor,

hoplomachos

(or,

as we

would

say,

drill-

sergeant),

does

not

appear

in

surviving

literature

before

Theophrastus

(fourth-third

century

B.C.),

but

it

may

well

have been

in

use earlier.27

The comment

3.

Use

of

battle-ax

in the attack

posture.

Detail of an

Attic

red-figured

volute-krater,

ca.

450

B.C.

The

Metropolitan

Museum of

Art,

Rogers

Fund,

1907,

07.286.84

4. A

Greek

in

the attack

posture

using

a

sword

in an

underhand thrust.

Detail of an Attic

red-figured

volute-krater,

ca.

450

B.C.

The

Metropolitan

Mu-

seum

of

Art,

Rogers

Fund,

1907,

07.286.84

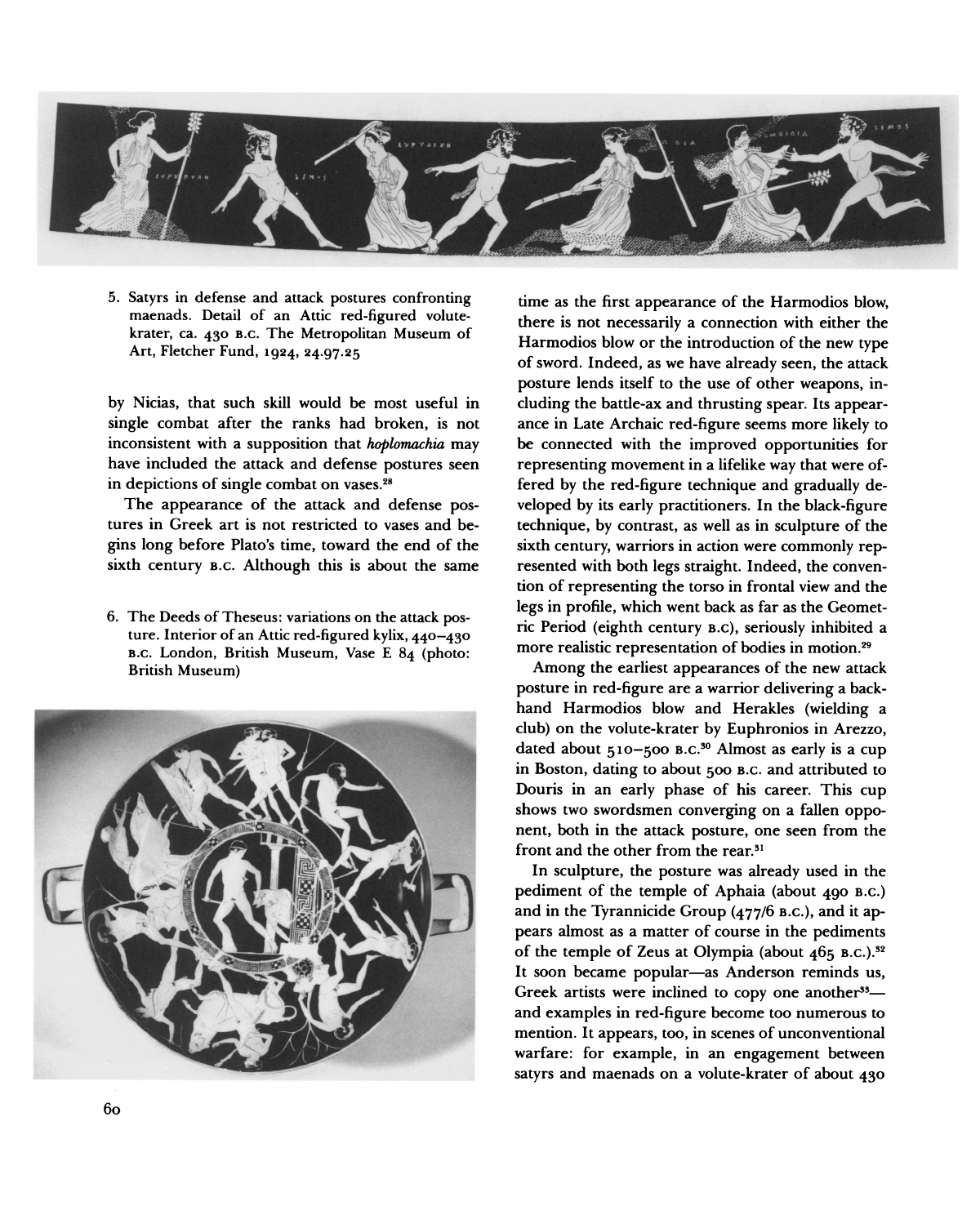

5.

Satyrs

in

defense

and

attack

postures

confronting

maenads. Detail

of an Attic

red-figured

volute-

krater,

ca.

430

B.c. The

Metropolitan

Museum of

Art,

Fletcher

Fund,

1924, 24.97.25

by

Nicias,

that such skill

would be

most useful in

single

combat after the

ranks had

broken,

is not

inconsistent with a

supposition

that

hoplomachia may

have included

the

attack and

defense

postures

seen

in

depictions

of

single

combat on vases.28

The

appearance

of

the attack and

defense

pos-

tures

in

Greek art

is not

restricted to vases

and be-

gins

long

before

Plato's

time,

toward the

end

of

the

sixth

century

B.C.

Although

this is about

the same

6.

The

Deeds

of

Theseus: variations on

the attack

pos-

ture. Interior of

an

Attic

red-figured

kylix, 440-430

B.C.

London,

British

Museum,

Vase

E

84

(photo:

British

Museum)

I

time as

the first

appearance

of the

Harmodios

blow,

there is

not

necessarily

a

connection with either

the

Harmodios

blow

or

the introduction of

the

new

type

of

sword.

Indeed,

as we

have

already

seen,

the

attack

posture

lends

itself to

the use of

other

weapons,

in-

cluding

the

battle-ax

and

thrusting spear.

Its

appear-

ance

in

Late

Archaic

red-figure

seems

more

likely

to

be

connected with

the

improved opportunities

for

representing

movement in a

lifelike

way

that

were

of-

fered

by

the

red-figure technique

and

gradually

de-

veloped by

its

early

practitioners.

In

the

black-figure

technique, by

contrast,

as well

as

in

sculpture

of

the

sixth

century,

warriors in

action were

commonly

rep-

resented with

both

legs

straight.

Indeed,

the conven-

tion

of

representing

the

torso in frontal

view

and

the

legs

in

profile,

which

went back as far as the

Geomet-

ric

Period

(eighth

century

B.c),

seriously

inhibited a

more

realistic

representation

of

bodies in

motion.29

Among

the

earliest

appearances

of the

new

attack

posture

in

red-figure

are

a

warrior

delivering

a

back-

hand

Harmodios

blow

and

Herakles

(wielding

a

club)

on

the

volute-krater

by

Euphronios

in

Arezzo,

dated

about

510-500

B.C.30 Almost as

early

is a

cup

in

Boston,

dating

to

about

500

B.C. and attributed

to

Douris in

an

early

phase

of his

career.

This

cup

shows two

swordsmen

converging

on a fallen

oppo-

nent,

both

in

the attack

posture,

one seen

from

the

front and

the

other from the

rear.3'

In

sculpture,

the

posture

was

already

used in

the

pediment

of the

temple

of

Aphaia

(about

490

B.c.)

and in

the

Tyrannicide

Group

(477/6

B.C.),

and

it

ap-

pears

almost

as

a matter of course

in

the

pediments

of

the

temple

of

Zeus at

Olympia

(about

465

B.C.).32

It soon

became

popular-as

Anderson

reminds

us,

Greek

artists were

inclined

to

copy

one

another3--

and

examples

in

red-figure

become

too

numerous

to

mention.

It

appears,

too,

in

scenes

of

unconventional

warfare: for

example,

in

an

engagement

between

satyrs

and

maenads

on a

volute-krater

of

about

430

6o

B.C.

(Figure

5).34

On

the

right,

a

satyr

adopts

the ca-

nonical attack

posture,

with

left

leg

and arm ad-

vanced

simultaneously,

against

a

retiring

maenad.

His

companion

on

the

left,

however,

is forced back

into the defense

posture

as

a more

aggressive

maenad threatens to deliver

a

particularly

painful

blow with the butt

end

of

her

thyrsos.

As

the

stance

proved

not

merely

useful

but ver-

satile,

it

was

adopted by

Greek artists

for

use

in a

variety

of

circumstances.

A

selection

is

conveniently

illustrated on a

single

cup

in the British Museum

showing

the

Deeds

of Theseus

(Figure

6).35

Against

the sow of

Crommyon,

Theseus uses

the attack

pos-

ture

with

a conventional underhand sword thrust

(upper

left).

Procrustes is attacked

with his own ax

(upper right),

wielded overhead as

in the

Centauro-

machy

discussed earlier:

again

there

is

no

danger

of

a

counterattack.

Sciron's

footbath,

also

conveniently

at

hand,

provides

an

unconventional

weapon

to be

used

in

the same fashion.

In

the central

tondo,

The-

seus

is no

longer

in

actual

combat,

but the artist

shows him

using

the same stance as he

pulls

the

Mi-

notaur's

corpse

out of the

Labyrinth.

Sculptors

were also

quick

to share the enthusiasm

of

vase-painters

for this

posture,

which lends itself so

freely

to a

variety

of

situations

and,

especially

in

battle-scenes,

both

serves

(or

so it

seems)

as a remi-

niscence of a movement

used

by

actual swordsmen

and

provides

the artist with

figures

in a whole

range

of

poses

for

incorporation

in

his

composition.

7.

Greeks in the attack

posture

against

Amazons.

De-

tail of a

frieze from the Mausoleum at Halicarnas-

sus,

ca.

350

B.C.

London,

British

Museum,

Sculp-

ture

1014

(photo:

British

Museum)

Throughout

the Greek

world,

the

posture appears

constantly

in

sculptured

scenes

of

battle.

By

the time

of the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus

(mid-fourth

cen-

tury

B.C.)

it had

become

a

cliche,

employed particu-

larly blatantly

on a slab

formerly

attributed

to

Scopas

(Figure

7).36

Here,

separated

only by

an Amazon in

the

defense

posture,

desperately

wielding

her battle-

ax in

a manner that leaves

her

totally

exposed

to a

sword-thrust,

are two Greeks

shown

facing

to

the

right

in the attack

posture.

Each leans forward

on a

bent left

leg,

his

body continuing

the

line

of his

right

leg

stretched out

in

a

straight

line behind.

The

only

significant

difference is

that one leans farther

for-

ward,

at a

sharper

angle

to the

ground.

From the

sculptor's point

of

view,

both contribute

conveniently

to

the

system

of

interlocking

diagonal

lines

that binds

together

the whole

composition

of the Amazon frieze

of

the Mausoleum. On the

adjacent

slab

(Figure

8)

a

Greek

provides

a

corresponding

set of

diagonals

pointing

in the

opposite

direction as he

adopts

an ex-

treme form of the defense

posture

under

the on-

slaught

of an

Amazon,

who herself uses

the attack

posture,

wielding

her battle-ax

overhead

with

one

hand

as

she

pushes

the Greek's

shield aside

with the

other.37

The

posture

was to

have a

long

history

in

ancient

art,

lasting

well

into

the

Roman

period.

Its nadir is

perhaps

to be found in

Macedonia,

on the celebrated

lion-hunt

mosaic from Pella.38

Hunting

lions and

other

dangerous game

with

spears

had been an artis-

8. A

Greek

in

the defense

position yielding

to an

Ama-

zon.

Detail of

a

frieze

from

the

Mausoleum

at Hali-

carnassus,

ca.

350

B.C.

London,

British

Museum,

Sculpture

1015

(photo:

British

Museum)

61

tic

convention in

Greece

for several

centuries.39 In

the

Macedonian

mosaic,

the

lion

is attacked

from

both

sides,

by

a

swordsman on the

spectator's right

and

by

a

spearman

on the left. The swordsman

adopts

the attack

posture,

with his

weapon

held over-

head for a

Harmodios blow. Neither his

weapon

nor

the

way

he uses it is

really

suitable

for

engaging

a

lion. A

spear

is

certainly

a more sensible

weapon

for

the

task,

but

only

when

properly

used. The

spear-

man's

legs

are

in

the attack

position,

but

turned

in

the

wrong

direction.

In

fact,

the

legs

of both men are

represented

in similar

fashion,

although

both their

actions and

their

positions

relative

to

the

lion are

dif-

ferent.

The

stance, therefore,

is used

merely

as

an

artistic

convention,

without

regard

for its

original

form and function.

Unfortunately,

the sort

of

com-

ment

on

such

inept

footwork that

might

have been

made

by

one of the

hoplomachoi

who

drilled the

ephebes

remains

among

the

many things

not recorded

by

ancient

authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The

ideas

put

forward

here

have been

discussed

with

various

colleagues,

and I am

particularly

grateful

to Mi-

chael

Crawford

for

help

with

the

bibliography

of

ancient

warfare and

to

Philip

Lancaster for

advice on

swords-

manship

and

its

terminology.

For

any

errors of fact or

interpretation

I

remain

solely

responsible.

ABBREVIATIONS

Anderson-J.

K.

Anderson,

Military Theory

and

Practice

in the

Age of

Xenophon

(Berkeley/Los

Angeles,

1970)

ARV2-J.

D.

Beazley,

Attic

Red-figure Vase-painters

(2d

ed.

Oxford,

1963)

Pritchett-W.

Kendrick

Pritchett,

The Greek

State

at

War II

(Berkeley/Los

Angeles/London,

1974),

IV

(Berkeley/Los

Angeles/London,

1985)

Shefton-B. B.

Shefton,

"Some

Iconographic

Remarks

on

the

Tyrannicides,"

American

Journal

of

Archaeology

64

(1960)

pp.

173-179

NOTES

1.

Anderson,

p.

84;

Pritchett,

II,

pp.

208ff.,

esp.

219-221

for

training during campaigns.

2.

Anderson

(p.

87

with n.

7)

points

out

that

there

is no Greek

account of sword exercise like that recommended

for the train-

ing

of Roman

legionaries

in

Vegetius,

De re militari

I,

12.

3. Anderson,

pp.

87-89.

4.

Xenophon,

Anabasis

I,

2.17;

VI,

5.25-37.

For

company-

drill,

see

Xenophon,

Cyropaedia

II,

3.21-22;

drill for

larger

units,

see ibid.

4.2-5.

5.

Anderson,

p.

87.

6.

Shefton,

pp.

173-179.

7.

Naples,

G

103,

104:

G.

Lippold,

Die

griechische

Plastik

(Mu-

nich,

1950)

p.

107

n.i

(bibl.),

pl.

34,

nos.

3-4;

Martin

Robert-

son,

History

of

Greek Art

(Cambridge,

1975)

pp.

185, 647 n.49

(bibl.).

8.

Red-figured

hydria

attributed to

the Nausikaa

Painter,

New

York, MMA,

25.28;

ARV2,

p.

llo,

no.

41

(bibl.).

Red-

figured squat lekythos

attributed to the

Eretria

Painter,

New

York,

MMA,

31.11.13;

ARV2,

p.

1248,

no.

9

(bibl.).

9.

Shefton,

p.

173.

o1.

On

a wound in the

armpit,

see

J.

Frel,

"The Volneratus

Deficiens

by

Cresilas,"

MMAB

n.s.

29

(1970-71)

pp.

170-177,

esp. fig.

9;

idem,

"The Wounded Warrior

in

New

York and Lon-

don,"

Archiologischer

Anzeiger

1973,

pp.

120-121.

11.

On

linen

corselets,

see

Anderson,

p.

23

with

nn.47-51.

12.

Homer,

Iliad

XVI,

114-123.

For

a

discussion,

with

other

references to

spears

broken

in

combat,

see

Pritchett, IV,

p.

56

with

n.167;

see also

Shefton,

p.

174.

In Attic

red-figure,

repre-

sentations of a sword-slash used

against

a

spear-blow

are

partic-

ularly frequent

in scenes of combat

between a Greek

hoplite

armed with

a

spear

and

a

Persian

with a sword:

see Anne

Bo-

von,

"La

representation

des

guerriers perses

et la notion de bar-

bare dans

la

're

moitie

du Ve

siecle,"

Bulletin de

Correspondance

Hellnique

87

(1963)

esp.

pp.

579-591.

13.

Shefton,

p.

173:

The Harmodios

blow is

often

repre-

sented

with the shield moved

back,

perhaps

for

balance,

but

Shefton,

p.

176,

also sees the

forward thrust

of the left arm

(without shield)

as intended to

maintain balance.

14.

Ibid.,

p.

173,

with n.6.

15.

Red-figured

volute-krater

attributed

to the Painter

of

the

Woolly Satyrs,

New

York,

MMA,

07.286.84;

ARV2,

p.

613,

no.

1

(bibl.).

16.

Shefton,

pp.

173

with

n.3,

174.

17.

Ibid.,

p.

175.

On

the use

of

straight

swords

(for

thrusting)

and curved swords

(for

slashing)

in

vase-painting,

see

Ander-

62

son,

p.

37.

The

archaeological

evidence for the two

types

is

as-

sembled

by

A.

Snodgrass,

Arms

and Armour

of

the Greeks

(Lon-

don,

1967)

p.

97;

see

also

Pritchett,

IV,

p.

61

n.183.

On the

"cut

and thrust"

sword,

see

also

A.

Snodgrass,

Early

Greek Armour

and

Weapons

(Edinburgh,

1964)

pp.

104

(use),

205

(origin).

At

this

early

period,

at least

in

art,

a blow with the

edge

of a sword

was

more common

than a

thrust:

G.

Ahlberg,

Fighting

on Land

and

Sea

in Greek

Geometric

Art

(Stockholm,

1971)

pp.

47ff.

The

use

of

the

edge

and the

point

in

vase-painting

was also studied

by

H.

Lorimer,

"The

Hoplite

Phalanx,"

Annual

of

the British School

at

Athens

42

(1947)

pp.

76-138,

esp.

119,

cited

by

Pritchett, IV,

p.

60,

where he

quotes

Vegetius,

De re militari

(I.12),

to

the

effect

that

in

practice

a blow with

the

edge

of a

sword

rarely

kills,

while

a

stab

is

generally

fatal.

18.

E. K.

Borthwick,

"Two Scenes

of Combat

in

Euripides,"

Journal

of

Hellenic

Studies

90

(1970)

p.

18.

19. Detail

from

the same

vase as

Figure

3;

see

note

17.

20.

The "underarm

thrusting position"

for the use of the

spear,

illustrated in Peter

Connolly,

The Greek Armies

(London,

1977),

is

very

similar,

the rear

leg being

almost

straight

with

the

heel

off the

ground.

On the overhead and underhand

use of

the

spear,

see

Pritchett, IV,

p.

60

with

nn.177-179.

Drill-

movements

with

the

spear

and the words

of command are dis-

cussed

by

Anderson,

pp.

88-89,

91

n.22.

21.

Xenophon,

Memorabilia

III,

12.5,

discussed

by

Pritchett,

II,

p.

211

and

IV,

pp.

63-64

with

n.195.

22.

Thucydides

II,

38-39

(Pericles's

Funeral

Oration).

Pritch-

ett

(II,

p.

21

1)

comments that the Athenians were nonetheless

panic-stricken

on

confronting

the

Spartans

at

Sphacteria

(Thu-

cydides

IV,

34.

1).

For a discussion of what was almost a

literary

commonplace

(references

in

Galen, Lucian,

Philostratus,

Plato,

Plutarch,

and

Xenophon),

see

Pritchett, II,

pp.

213ff.

Plato

(Laws,

829ab)

stressed that athletic

training

should be aimed at

agility

rather than

mere

strength. Agility

was also fostered

by

the dance in armor

(Pyrrhic),

and

Anderson

(pp.

92-93)

sug-

gested

that it

may

have been used

to

teach basic drill-

movements,

but

representations

in

vase-painting

do

not include

postures

like those discussed here

in

connection

with

swords-

manship.

The

Pyrrhicist

is often

shown

looking

back over

his

shoulder: see

J.-C.

Poursat,

"Les

representations

de danse ar-

mee dans

la

ceramique attique,"

Bulletin

de

Correspondance

Helle-

nique

92

(1968)

pp.

550-615.

For

further references on the

Pyrrhic

with discussion

of various

controversies,

see

Pritchett,

IV,

pp.

61-63.

For

Etruscan

parallels

see G.

Camporeale,

"La

Danza Armata in

Etruria,"

Melanges

de

l'cole

Franfaise

de

Rome,

Antiquite

99

(1987)

pp.

11-42.

23.

Pritchett, II,

p.

208

n.3;

see also

Anderson,

p.

86,

citing

J.

Delorme,

Gymnasion

(Paris,

1960) 27;

contrast

Humphreys,

Journal

of

Hellenic Studies

94 (1974)

p.

90,

who

sees

"little evi-

dence of

[Delorme's]

association between the

gymnasium

and

the

hoplite."

24.

Plato,

Laws,

813e;

Anderson,

p.

86.

25.

G.

L.

Cawkwell,

"Epaminondas

and

Thebes,"

Classical

Quarterly

66

(n.s.

22,

1972)

p.

262

n.4.

I

remember

introducing

Helmut

Nickel to

Evelyn

Waugh's

trilogy,

Sword

of

Honour-and

his comment:

"All armies

are alike!"

26.

Plato,

Laches

181e-183d;

Anderson,

p.

86.

27.

H. D. Liddell

and R.

Scott,

A

Greek-English

Lexicon

(new

ed.,

H. Stuart

Jones

and

R.

McKenzie, eds.,

Oxford,

1925-40)

s.v.

28.

Vase-painters

generally

chose

to

portray

scenes

consisting

of a series

of

single

hand-to-hand

combats

rather

than

fighting

in

formation.

For the

Chigijug

with its

massed

ranks,

and

other

early examples,

see Lorimer

(n.

7).

Pritchett

(IV,

p.

91)

com-

ments that

vase-painters'

preference

for

open

scenes

also

ruled

out

representations

of

concerted

pushing

(othismos).

29.

Among

rare

examples

in

black-figure

vase-painting

of

striding figures

with a

bent

forward

leg

is a warrior

on the

hy-

dria,

Leyden

P.C.

44

(J.

D.

Beazley,

Attic

Black-figure

Vase-

painters

[Oxford,

1956]

p. 106,

no.

132;

D. von

Bothmer,

Ama-

zons

in Greek

Art

[Oxford,

1957]

p. 8,

no.

24,

pl.

13).

A

warrior

near

(and

partly

below)

the

handle of a

neck-amphora

attrib-

uted to the

Polyphemos Group,

at first

sight

in

the

classic attack

posture

(left

knee

bent,

right leg

stretched

out

behind,

left

arm

bent,

sword in hand for an underarm

thrust)

is

actually being

forced to his knees

by

an overarm

spear-thrust

from

his

oppo-

nent

(E.

Langlotz,

Martin von

Wagner-Museum

der

Universitat

Wurzburg,

Griechische

Vasen,

p.

87,

no.

455,

pl.

133).

A similar

posture

occurs in Laconian

black-figure

as

early

as about

550

B.C.

for a hunter

pursuing

a boar

with a

spear, perhaps

an

anomalously early

version of the attack

posture:

Louvre E

670;

P. E.

Arias,

B.

B.

Shefton,

M.

Hirmer,

A

History

of

Greek

Vase

Painting

(London,

1962)

p.

309

(bibl.),

pl.

73

above.

30.

Arezzo

1465;

ARV2,

p.

15,

no.

6

(bibl.).

31.

Boston

00.338;

ARV2,

p.

427,

no.

4

(bibl.).

32.

D.

Ohly,

Die

Aegineten

(Munich,

1976)

I,

esp.

Beilage

E

and

pls.

12,

55;

note

also

on

pl.

58

that the rear heel is

off

the

ground:

see also

n.20.

For the

temple

of Zeus at

Olympia,

see

B.

Ashmole

and

N.

Yalouris,

Olympia,

The

Sculptures

of

the

Temple

of

Zeus

(London,

1967)

pl.

95.

33.

Anderson,

p.

87.

34.

Red-figured

volute-krater

with

stand,

New

York,

MMA

24.97.25.

G.

M.

A. Richter and L.

F.

Hall,

Red-figured

Athenian

Vases

in The

Metropolitan

Museum

of

Art

(New

York,

1936)

pp.

161-162,

pl.

127.

35.

London,

British Museum E

84

(GR

1850.3-2.3),

kylix

at-

tributed

to the

Codrus

Painter,

ARV2,

p.

1269,

no.

4

(bibl.).

The

scene of

Theseus

wrestling

with

Kerkyon

is

cited

by

Borthwick,

"Two Scenes of

Combat,"

p.

19,

to illustrate

the

"Thessalian

trick,"

a

wrestling

movement

adapted

to

swordsmanship by

Eteocles in

Euripides,

Phoinissai

1407-1413.

36.

London,

British

Museum,

Sculpture

1014

(GR

1857.12-

20.269).

The attribution to

Scopas

was first made

by

the exca-

63

vator

of

the

Mausoleum,

C. T.

Newton,

in

1857

and has

been

widely

accepted.

For reasons

why

the attribution is

no

longer

tenable,

see

B. F.

Cook,

"The

Sculptors

of the

Mausoleum

Frieze" in

Architecture and

Society

in

Hecatomnid Caria

(conference

proceedings,

Uppsala,

1987,

forthcoming).

37.

London,

British

Museum,

Sculpture

1015

(GR

1857.12-

20.268).

38.

Ph.

Petsas,

"Mosaics from Pella"

in

La

mosaique greco-

romaine

(colloquium papers,

Paris,

1963 [1965])

pp.

41-56,

figs.

3,4-

39.

K. Friis

Johansen,

Les

vases

sicyoniens

(Paris/Copenhagen,

1923)

p.

149.

64