Pilavcioglu, Burak et al.

Article

Memes everywhere: The effect of social media memes

on consumers' attitude towards brands and their

purchase intention

PraxisWISSEN Marketing

Provided in Cooperation with:

AfM – Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Marketing

Suggested Citation: Pilavcioglu, Burak et al. (2023) : Memes everywhere: The effect of social media

memes on consumers' attitude towards brands and their purchase intention, PraxisWISSEN

Marketing, ISSN 2509-3029, Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Marketing (AfM), Berlin, Vol. 8, Iss. 01/2023,

pp. 37-55,

https://doi.org/10.15459/95451.59

This Version is available at:

https://hdl.handle.net/10419/289792

Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen:

Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen

Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden.

Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle

Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich

machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen.

Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen

(insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten,

gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort

genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte.

Terms of use:

Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your personal

and scholarly purposes.

You are not to copy documents for public or commercial purposes, to

exhibit the documents publicly, to make them publicly available on the

internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public.

If the documents have been made available under an Open Content

Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you may exercise

further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence.

Future of Marketing

Organ der Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Marketing (AfM)

http://arbeitsgemeinschaft.marketing/praxiswissen-marketing

ISSN 2509-3029 Heft 1/2023

Herausgeberinnen im Auftrag der AfM:

Prof. Dr. Andrea Bookhagen

Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft Berlin (HTW)

Campus Wilhelminenhof

Wilhelminenhofstraße 75A

D-12459 Berlin

E-Mail: [email protected]

Prof. Dr. Annett Wolf

Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft Berlin (HTW)

Campus Treskowalle

Treskowallee 8

D-10318 Berlin

E-Mail: [email protected]

Beirat:

Prof. Dr. Mahmut Arica (FOM Hochschule für Oekonomie & Management, Münster) | Prof. Dr. Matthias Johan-

nes Bauer (IST Düsseldorf) | Prof. Dr. Monika Gerschau (HS Weihenstefan-Triesdorf) | Prof. Dr. Marion

Halfmann (HS Niederrhein) | Prof. Dr. Annette Hoxtell (HWTK Berlin) | Prof. Dr. Karsten Kilian (HS für

angewandte Wissenschaften Würzburg-Schweinfurt) | Prof. Dr. Ingo Kracht (TH Ostwestfalen-Lippe) | Prof. Dr.

Alexander Magerhans (Ernst-Abbe-Hochschule Jena) | Prof. Dr. Annette Pattloch (Berliner Hochschule für

Technik) | Prof. Dr. Jörn Redler (HS Mainz)

Cover-Gestaltung: Vanessa van Anken | Web: www.vananken.design

Impressum

Kaum eine andere Disziplin in der Betriebswirtschaft zeichnet sich aktuell durch einen

so starken Veränderungsprozess aus wie das Marketing. Themen wie KI und Digi-

talisierung oder Nachhaltigkeit und Purpose führen nicht nur zu neuen Geschäftsmo-

dellen, sondern verändern z. B. auch die Kommunikation zwischen Unternehmen und

Kundinnen und Kunden. Immer vielfältigere Themen werden zum Gegenstand der

Diskussion in Wissenschaft und Praxis.

So ist es auch nicht überraschend, dass sich zum Thema „Future of Marketing“ bei

Google ungefähr 2,2 Milliarden Ergebnisse finden lassen (Stand 29.08.2023).

Dies greift auch die Ausgabe 1/2023 der PraxisWISSEN Marketing auf, in der die

Marketingcommunity Antworten auf die Frage nach der Zukunft des Marketing

gibt.

Die Frage nach der Zukunft der Marketinglehre war im Übrigen vor 50 Jahren Aus-

gangspunkt für die Gründung der Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Marketing (AfM). Wir

werfen daher auch einen Blick auf die Anfänge und die Zukunft der AfM.

Die heutigen Entwicklungen berücksichtigend kann man fragen, ob gar das Marketing

zu Ende ist und sich zukünftig als Teil der Unternehmenskommunikation wieder

findet. Unabhängig von dieser Einordnung sind nicht nur kontinuierlich neue Inhalte,

sondern auch neue Formen der Gestaltung und Verbreitung in den sozialen Medien

zu beobachten. Ein Beitrag diskutiert z.B. die Wirkung von Memes in sozialen Me-

dien, also kreative Inhalte, die sich vorwiegend viral ausbreiten. Es wird gefragt, wie

sich Memes auf die Einstellung der Verbraucherinnen und Verbraucher gegenüber

Marken auswirken.

Andere Autorinnen und Autoren gehen einen Schritt weiter und erkunden Marketing-

möglichkeiten und potenzielle Fallstricke im Metaverse. Sie zeigen das Potenzial

des Metaverse für personalisierte und immersive Marketingstrategien auf. Die Ent-

wicklung von Communities, sowie innovative Metaverse-Produkte, wie z.B. NFTs, wer-

den als besonders vielversprechend angesehen. Ebenso wird die Zukunft von Mar-

kenkommunikation und Werbung im Metaverse diskutiert.

Auch die Marktforschungscommunity ist aufgerufen, die Zukunft der Informationsbe-

schaffung und -verarbeitung zu diskutieren. So stellt sich beispielsweise die Frage, wie

zukünftig Informationen gewonnen werden, welche z.B. für die Konzeption von

Marketingkampagnen genutzt werden. Geht es zukünftig um das „Fragen oder Zu-

hören?“. So werden in Kundenbefragungen und User Generated Content als Da-

tenquellen zur Erfassung der Kundenzufriedenheit miteinander verglichen oder allge-

mein klassische Marktforschungsansätze auf ihre Zukunftsfähigkeit hinterfragt.

Die Herausgeberinnen bedanken sich bei den Autorinnen und Autoren dieser Aus-

gabe, den Mitgliedern des Beirats, die den Review der Beiträge verantworten und allen

anderen Personen, die an der Entstehung dieser Zeitschrift beteiligt sind.

Berlin im September 2023

Andrea Bookhagen Annett Wolf

Vorwort

PraxisWISSEN Marketing 1/2023 S. 5

7

50 Jahre Arbeitsgemein-

schaft für Marketing (AfM) –

von Rosenheim bis nach

Mainz

77

Markenkommunikation und

Werbung im Metaverse.

Immersion und Interaktion in

Advergames und Adverworlds

Annett Wolf

Rötger Noetzel

Andrea Bookhagen

Andreas Hesse

11

„Ist das Marketing am

Ende?“

Status quo und Perspektiven

im Verhältnis von Marketing

und Unternehmenskommuni-

kation

91

Fragen oder Zuhören? Ein Ver-

gleich von Kundenbefragungen

und User Generated Content

Michael Bürker

Sebastian Oetzel

Denise Graf

37

Memes everywhere – The

effect of social media memes

on consumers’ attitude to-

wards brands and their pur-

chase intention

109

Die Messung des Images einer

Store Brand des Lebensmitte-

leinzelhandels – Entwicklung

und Anwendung einer

Multi-Item-Skala

Burak Pilavcioglu, Alexander Hodeck,

Niels Nagel, Marcus Simon,

Timo Zimmermann, Klaus Mühlbäck

Wolfgang Geise

Fabian A. Geise

57

Marketing in the Metaverse:

Exploring marketing opportu-

nities and potential pitfalls

135

Call for Papers

Künstliche Intelligenz (KI) im

Marketing

Stefanie Wannow

Chiara Beck

Inhalt

PraxisWISSEN Marketing

PraxisWISSEN Marketing 1/2023 DOI 10.15459/95451.59 S. 37

AfM

Arbeitsgemeinschaft

für Marketing

eingereicht am: 07.02.2023

überarbeitete Version am: 26.04.2023

überarbeitete Version am: 01.09.2023

Memes everywhere – The effect of social

media memes on consumers’ attitude to-

wards brands and their purchase intention

Burak Pilavcioglu, Alexander Hodeck, Niels Nagel, Marcus Simon, Timo Zimmer-

mann, Klaus Mühlbäck

Mit der ungebrochenen Relevanz sozialer Medien und der ständigen Weiterentwick-

lung der Online-Kommunikation gewinnen Memes zunehmend an Popularität. Es gibt

es nur wenige wissenschaftliche Untersuchungen zur Werbewirksamkeit von Memes.

Die vorliegende Studie soll diese Wissenslücke schließen. Sie prüft, ob Memes einen

positiven Effekt auf die Einstellung der Konsumentinnen und Konsumenten zur Wer-

bung, zur Marke und auf die Kaufabsicht haben. Die Ergebnisse einer empirischen

Studie zeigen, dass Anzeigen mit Memes, auch wenn sie als humorvoll wahrgenom-

men werden, nicht signifikant besser abschneiden als Anzeigen der Kontrollgruppe.

With the literally ever-lasting relevance of social media and the constant development

of online communication, memes are more and more gaining popularity. So far there

is only little scientific research on the advertising effectiveness of memes. This study

aims to close this knowledge gap and tests, if memes have a positive effect on con-

sumers’ attitude towards the advertisement, towards the brand and on their purchase

intention. Results of an empirical study indicate that ads with memes, despite being

perceived as humorous, did not perform significantly better than control group ads.

Burak Pilavcioglu, M.A., Master an der International School of Management, München und Master an

der Edinburgh Napier University, Strategist bei The Game Group. burak.pilavcioglu@googlemail.com.

Prof. Dr. Alexander Hodeck, Promotion an der Sportwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität

Leipzig, Professur für International Sports Management an der International School of Management,

Berlin. alexander.hodeck@ism.de

Prof. Dr. Niels Nagel, Promotion an der Deutschen Sporthochschule Köln, Professur für International

Sports Management an der International School of Management, Köln. niels.na[email protected].

Prof. Dr. Marcus Simon, Promotion an der Universität des Saarlandes, Saarbrücken, Professur für

Marketing und Kommunikationswissenschaft an der International School of Management, München.

Prof. Dr. Timo Zimmermann, Promotion im Fachbereich Sportmanagement/ Sportökonomie an der

Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Professur für International Sports Management an der International School

of Management, Dortmund. timo.zim[email protected].

Prof. Dr. Klaus Mühlbäck, Promotion an der Wirtschaftsuniversität Bratislava, Fakultät für Internatio-

nalen Handel, Professur für Strategisches Marketing an der International School of Management, Mün-

chen. klaus.muehlbaec[email protected].

PraxisWISSEN Marketing

PraxisWISSEN Marketing 1/2023 DOI 10.15459/95451.59 S. 38

AfM

Arbeitsgemeinschaft

für Marketing

1. Introduction

Over the last decades, the development of the Internet up to Web 4.0 has changed

communication methods on a global scale (Almotairy; Abdullah; Abbasi 2020). Apart

from others, companies took advantage of the new communication channels and be-

gan to invest in social media marketing. Consumers could like the content or share it

within their social network. Ideally, companies create content which would then be

shared on a large scale and could attract attention to their products as the content

becomes viral.

The performance of social media marketing is constantly measurable as digital com-

munication methods allow companies to track relevant metrics such as engagement

rate, like-to-dislike ratio, number of views or comments.

There are certain forms of social media marketing which could enable further engage-

ment of potential customers, such as the use of humor and memes. With the increasing

usage of memes among young adults and younger generations, some brands follow

the latest trends and add entertaining and engaging content to their social media feeds.

They either create memes about their products and services or other types of humor-

ous content at varying degrees (Bond 2020).

The literature on the effectiveness of social media marketing is rich but needs more

research on memes and humorous posts in online communication strategies (Chuah;

Kahar; Ch'ng 2020). As there is a lack of research on the use of memes in social media

marketing, this study could provide a better understanding of the factors under which

such stylistic elements could have a positive or negative impact on consumers’ atti-

tudes towards the brand and hence their purchase intention.

2. Theoretical framework

As humor theories show, there are different types of humor that work in their own way

and can induce laughter. Humorous content can also be transmitted in social media,

just as it can in offline or traditional media. But social media has also contributed to the

sharing of new media formats, thus establishing new forms of humor, such as memes,

among others.

The word meme originates from the ancient Greek ‘mimema’, describing something

imitated (Shifman 2014). Dawkins proposed the meme as a “unit of cultural inheritance”

(Science Insider 2015, 0:30). Anything can be a meme, which can be communicated

from brain to brain, like tunes, images, instructions, or ideas. Davison (2012) defines

internet memes as “… a piece of culture, typically a joke, which gains influence through

online transmission”, while hereby the term ‘culture’ distinguishes memes from simply

humorous social media posts. He states that a meme consists of three components

manifestation, behaviour and the Ideal. Manifestation refers to all visible and actual

properties of the meme. Behaviour describes the actions taken by someone, who cre-

ated the meme. Ideal is the message which the meme creator tries to communicate

via the meme, which in the best case might influence culture (Davison 2012).

PraxisWISSEN Marketing

PraxisWISSEN Marketing 1/2023 DOI 10.15459/95451.59 S. 39

AfM

Arbeitsgemeinschaft

für Marketing

The meme visualizes the cultural relevance of the scenario described. Depending on

the context, the meme’s format is used to resemble for example awkwardness, sad-

ness, shocking or confusion and can be either sarcastic or truthful (Adam 2021).

Another difference between memes and humorous virals is that memes are continu-

ously spread with new captions of cultural relevance, while virals remain unchanged

and create hype in a short time and then disappear from the scene again. (Conti 2016)

When someone encounters a meme, a new song for example, he is likely to share this

song with his social environment, who then would also share that same song with their

social circle. The meme is starting to spread from brain to brain rapidly, like a virus

during a pandemic (Science Insider 2015, 0:45).

Blackmore et al (2000) identified already three measures, which make a meme a suc-

cessful one: fidelity, fecundity and longevity.

Fidelity is the meme’s ability to maintain its original information while it is being repli-

cated and transferred from one person to another. Here fidelity refers less to the literal

precise information transfer but more to the overall message and the underlying mean-

ing transmitted from one to another (Blackmore et al 2000). Therefore, a high fidelity

ensures that the original idea is conveyed, but also leaves space to evolve with modi-

fications and new alternations, which increases the lifespan of the meme as a result.

According to Blackmore et al (2000), successful memes are not those that are valuable

and beneficial to the recipient, but those that the recipient will remember later. Moreo-

ver, something that has high relevance to the recipient or a particular group of peers

and is fully understood by them, and therefore shared and replicated, is more likely to

become a good meme than something that is not understood by a majority of a larger

group of people (Knobel; Lankshear 2007).

Fecundity is described as the meme’s power, in which it can replicate and spread. The

quicker a meme can be replicated, the faster it will spread. Research added the sus-

ceptibility factor to the fecundity measure as a meme’s time and location features in

terms of someone’s receptivity to it and his willingness to be influenced by it (Knobel;

Lankshear, 2007). For susceptibility it is important how relevant the meme is for current

events, how it relates to already existing successful memes and which interests and

values are represented in the environment in which the meme is spread (Knobel 2006).

The better these conditions are, the greater the susceptibility, and therefore it is in

theory more likely that the meme will find resonance with others and thus will be passed

from one to another.

The third measure longevity states the more robust the medium is, in which an idea is

replicated, the longer the meme will survive and be shared with other people. The

longer a meme survives the longer it can be replicated (Knobel; Lankshear, 2007).

Written memes are therefore both high in fidelity and in longevity, as the manifested

idea leaves little room for error in the replication process (Blackmore et al. 2000).

Moreover, the success of a meme depends not only on these three factors, but also

on the medium through which the meme is replicated and disseminated. Online memes

can be copied, modified, and uploaded again relatively easy and fast in the internet,

which is why memes are high in fecundity. On top of that, the digital environment allows

memes to be replicated without any information loss. The internet provides various

platforms for diverse peer groups, in which individuals can share their memes with

PraxisWISSEN Marketing

PraxisWISSEN Marketing 1/2023 DOI 10.15459/95451.59 S. 40

AfM

Arbeitsgemeinschaft

für Marketing

people with similar interests, which enables a better understanding of the content. Con-

sequently, memes can be replicated and spread through digital networks more effi-

ciently, than through offline channels (Lintott 2016).

While research on memes generally accepts the meme concept, approaches vary on

explaining how exactly a meme is being replicated and spread. Because memes are

described as the cultural counterpart to the biological gene, the spread of memes is

oftentimes compared to the one of a virus or parasite (Heylighen; Chielens 2009), lit-

erally in four stages of meme reproduction. The first stage is assimilation. In Heylighen

& Chielens’ four stage model, assimilation refers to the point when someone is en-

countered to a meme. Using the virus comparison, this states that a meme must infect,

the recipient then becomes a new host of the meme. The meme has to be salient

enough to grab the recipient’s attention to be noticed.

The second stage is retention. Heylighen & Chielens postulate that memes only be-

come memes when they are stored in the host's memory for a certain period. They add

that the longer this period takes, the more opportunities the meme has to spread.

The third stage expression describes how the meme within the hosts memory is con-

verted to a physical format, so it can be expressed to other people. Heylighen &

Chielens state that expression can take the form of any media from speeches or pic-

tures created by the host but also unintentional ways of the hosts behaviour like body

language or visual appearances.

Once the meme has been converted to an expression, it is ready to enter the fourth

stage transmission. For the meme to be transmitted, the meme needs a physical stor-

age unit for the expression, which Heylighen & Chielens call vehicle. This is in accord-

ance with Shifman (2013), who also states that the essence of memes is transmitted

via meme vehicles. It is important that the vehicle is sufficient in carrying the infor-

mation of the meme without any loss or mistakes. Heylighen & Chielens (2009) also

proposed criteria, which influence the success of a meme’s replication throughout the

four stages. They divide these criteria into objective, subjective, intersubjective, and

meme-centered categories. Objective criteria are independent from the recipient, sub-

jective criteria rely on the recipient, intersubjective criteria are based on the interaction

of recipient and content and meme-centered criteria represent the meme’s character-

istics itself.

With the Internet and the development of digital social networks, communication

evolved on a digital level. Memes are nowadays not just a theoretical concept, for

which genes and viruses are used as a metaphorical analogy, but rather real thoughts

and material which is spread consciously from oneself to others (Shifman 2013). Da-

vison (2012) defines internet memes as “… a piece of culture, typically a joke, which

gains influence through online transmission”. He states that a meme consists of three

components: Manifestation, behaviour and the ideal. Manifestation refers to all visible

and actual properties of the meme. Behaviour describes the actions taken by some-

one, who created the meme. Ideal is the message which the meme creator tries to

communicate via the meme.

Another approach to define internet memes is that a meme is “an image, a video, a

piece of text, etc. that is passed very quickly from one internet user to another, often

with slight changes that make it humorous” (Oxford Learner Dictionaries, n.d.). The

PraxisWISSEN Marketing

PraxisWISSEN Marketing 1/2023 DOI 10.15459/95451.59 S. 41

AfM

Arbeitsgemeinschaft

für Marketing

term Internet meme refers to any content that appears on the Internet and is redistrib-

uted by other Internet users in an imitated or edited form (Dynel 2020). Therefore,

anyone can be a creator of new memes and participate. Shifman (2013) sees internet

memes as connected content spread by users to peers, which convey a specific

thought as a response to a certain socio-cultural context. The meme may appear in

any format, such as images, GIFs or videos, and can optionally contain text passages.

It is important to distinguish between a meme and a pure viral. A viral is content, often

an image or video, which is widely spread in unchanged form through digital word-of-

moth and quickly creates immense attention (Shifman 2013). The difference between

memes and virals is that memes are continuously spread with new captions and virals

remain unchanged, create a hype in a short time and then disappears from the scene

again. Conti (2016) also shares this view and highlights, that memes, in contrast to

viral content, are replicated with slight modifications. Furthermore, he states that a

meme is not simply an edited image. Rather memes are a piece of culture in which the

creator tries to communicate something to the respective subculture that the recipient

can easily relate to, understand, identify with, and modify.

Zittrain (2018) describes five factors, which influence the generativity of memes on the

internet and help to understand why and when memes are gaining in popularity. These

factors Zittrain refers to as generative technologies, are capacity for leverage, adapta-

bility, ease of mastery, accessibility, and transferability.

Capacity for leverage refers to technology making tasks easier to accomplish. In the

case of memes, this means any tool, which helps to create memes, such as Adobe

Photoshop but also palettes of meme templates. Today meme generators also exist in

the form of smartphone applications.

Adaptability refers to how well something can be modified to broaden its range of uses.

Every update of meme generating tools contributes to the ease of mastery factor, which

describes how easy users can understand and adapt to new technologies and use

them to create or adapt memes.

Zittrain describes accessibility as how easy the public has access to new technologies

to use, master and adapt a meme, e.g., to what extent the availability of mobile internet

and the bandwidth speeds are increasing globally. Transferability indicates how easily

changes can be conveyed to others. Zittrain states that in the internet environment it

is easy to replicate content. Given the simple language and structure of internet memes

and the fast information sharing environment of the internet, memes are easily trans-

ferable from one to another, which allows memes to evolve and replicate quickly in the

digital world.

Already Shifman (2014) attempted to classify memes into nine different categories,

which was criticized by Dynel (2016), who commented that memes are too complex

and constantly evolving, making it difficult to make a classification that is valid in the

long term.

This study focuses on image-based memes. In image-based memes, the graphical

element is often a snapshot or clip of pop culture, politics, or everyday situations and

serves as the basis for later reproduction. It is usually characterized by images with a

text caption placed on, above, or next to the image (Osterroth 2015). For example,

some memes relate to political issues, while others relate to social or economic issues

PraxisWISSEN Marketing

PraxisWISSEN Marketing 1/2023 DOI 10.15459/95451.59 S. 42

AfM

Arbeitsgemeinschaft

für Marketing

(Wiggins, 2019). Consequently, the shared understanding of the context between the

meme creator and the recipient is necessary for the recipient to understand the meme

and the underlying humor (Gleason et al. 2019).

However, intertextuality is as well an important factor. Intertextuality refers to an im-

age’s or text's reliance on additional outside information to achieve deeper meaning

than the image or text itself could achieve. Therefore, memes rely not only on the view-

er's knowledge of the meme template itself, but also on the viewer's general knowledge

of culture, the situational context and humor to understand the intended references

that the meme's creator aims to communicate. After all, image-based memes show in

a context-related way how the internet community reacts to certain political or social

stances and are thereby a tool to participate in politics and society (Shifman, 2013).

These days, many brands have started to use memes in their social media marketing

channels, as they have realized that memes are an effective way to communicate

online and attract the attention of customers (Bury 2016). Bury compares memes as

marketing instrument with the usage of celebrity endorsements and states that con-

sumers are familiar with the concept of memes in their everyday life. Compared to

traditional marketing campaigns, such as TV advertisements or sponsorships, memes

are not only way more cost efficient, but are also nearly identical to memes created by

consumers, which makes it difficult for the audience to determine whether the meme

is created by a company or another internet user, unless the meme is posted on the

company’s social media channel.

Brubaker et al (2018) encourage companies to not only see value in memes as a com-

munication tool from brand to consumer, but to also pay attention to memes created

by consumers, which refer to the brand, as this is a great opportunity to gain customer

feedback. This opinion is also shared by Csordás et al (2017), who suggest that

memes about corporations created by consumers give an indication on how the cus-

tomers perceive the brand in a non-market research environment. Chuah et al (2020)

point out, that memes are an effective tool to especially reach a younger customer

segment.

Despite its relevance in today’s online media consumption, memes bring also risks to

companies, as they cannot control how the audience will react to their postings and

they must be aware of a potential backfire from the online audience. The underlying

message, which the meme tries to communicate might be decoded differently by indi-

viduals based on their own experiences and background (Murray et al. 2014). The

internet also has its dark side, as memes can be used to cyberbully an individual, a

peer group or companies and organizations (Casey 2018). Brands could as well fail to

create memes, which meet the expectations and tonality of the respective target group.

PraxisWISSEN Marketing

PraxisWISSEN Marketing 1/2023 DOI 10.15459/95451.59 S. 43

AfM

Arbeitsgemeinschaft

für Marketing

3. Objectives and methodology

The main research questions underlying this study are whether meme content in so-

cial media marketing can increase brand liking and improve sales for high respec-

tively low involvement brands.

In particular the following leading research questions should be answered:

• Do humorous meme posts increase ad likeability?

• Do humorous meme posts increase brand likeability?

• Do humorous meme posts increase the purchase intention?

• Do humorous meme posts increase the recall of brands?

• Are there significant differences between low-involvement and high-involvement

brands with such regards?

Based on research implications of positive affect and affect transfer models as well as

findings on advertising effectiveness of humor, this study assumes a mediating effect

of positive affect on the dependent variables ad and brand likeability and purchase

intention. Based on the Elaboration Likelihood Model (Petty; Cacioppo 1986) this re-

search assumes that peripheral cues, in this case humor in memes, have a stronger

effect on low involvement products than on high involvement products. Finally, this

study suggests that memes are likely to increase the recall towards the brand.

This leads to the following hypothesis:

• H1a: If the social media post of a high involvement brand contains a meme, then

the attitude towards the ad will be higher, than a social media post of a high involve-

ment brand without a meme.

• H1b: If the social media post of a low involvement brand contains a meme, then the

attitude towards the ad will be higher, than a social media post of a a low involve-

ment brand without a meme.

• H1c: If the social media post of a low involvement brand contains a meme, then the

attitude towards the ad will be higher, than a social media post of a high involvement

brand with a meme.

• H2a: If the social media post of a high involvement brand contains a meme, then

the attitude towards the brand will be higher, than a social media post of a high

involvement brand without a meme.

• H2b: If the social media post of a low involvement brand contains a meme, then the

attitude towards the brand will be higher, than a social media post of a low involve-

ment brand without a meme.

• H2c: If the social media post of a low involvement brand contains a meme, then the

attitude towards the brand will be higher, than a social media post of a high involve-

ment brand with a meme.

PraxisWISSEN Marketing

PraxisWISSEN Marketing 1/2023 DOI 10.15459/95451.59 S. 44

AfM

Arbeitsgemeinschaft

für Marketing

• H3a: If the social media post of a high involvement brand contains a meme, then

the purchase intention will be higher, than a social media post of a high involvement

brand without a meme.

• H3b: If the social media post of a low involvement brand contains a meme, then the

purchase intention will be higher, than a social media post of a low involvement

brand without a meme.

• H3c: If the social media post of a low involvement brand contains a meme, then the

purchase intention will be higher, than a social media post of a high involvement

brand with a meme.

• H4. If a social media post contains a meme, then the recall of the brand will be high

than from a social media post without a meme.

For this study and the aim to generalize findings, quantitative research was chosen, in

particular a experimental between-subject design. This means that all participants in

the experiment were tested with only one treatment each during the experiment. The

study evaluates group differences between participants with different treatments. In

particular the participants were compelled to pick up on distinct differences, make rat-

ings and hence illustrate effects in a more salient way.

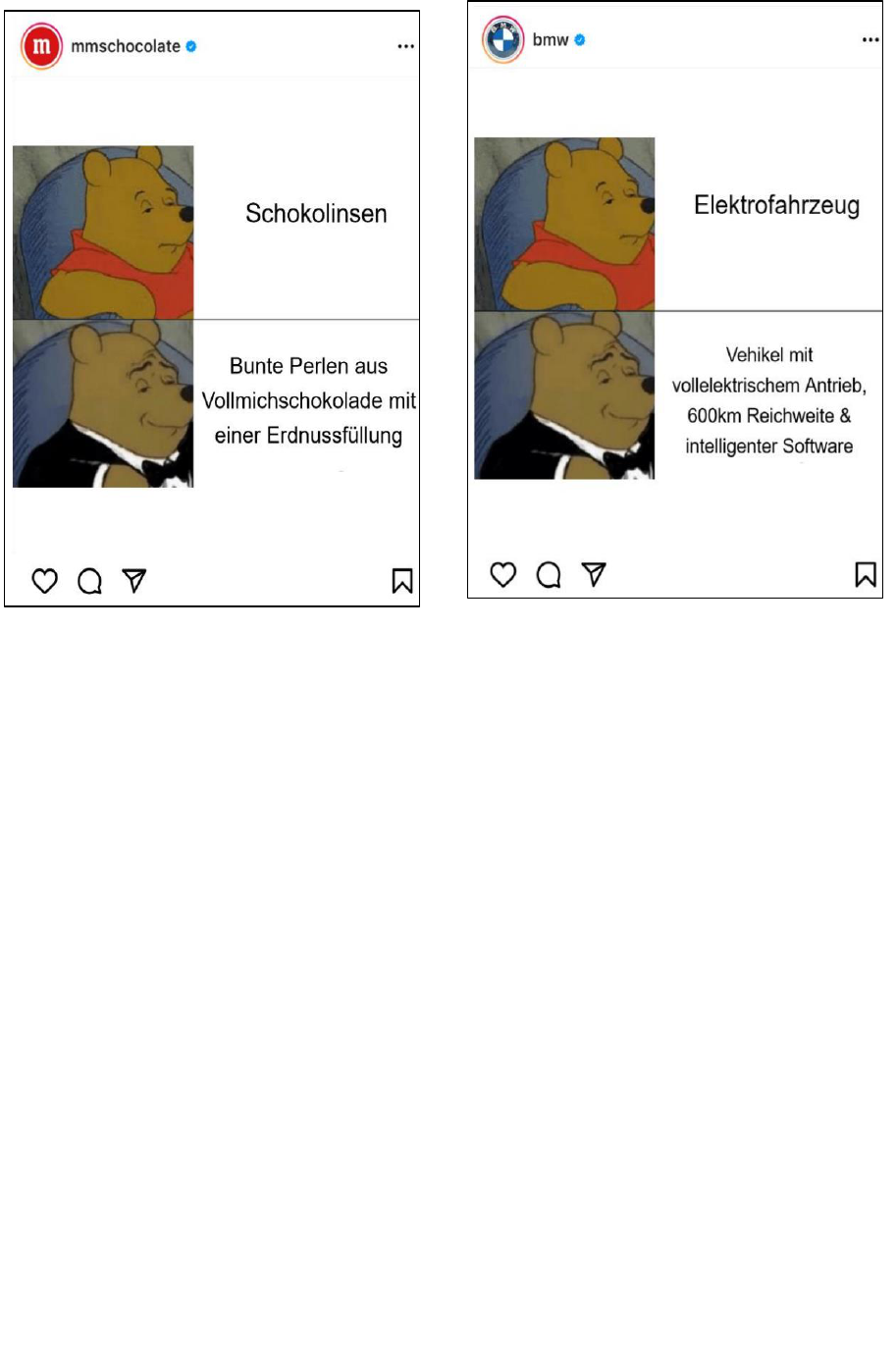

Four different social media postings (see figures 1 to 4) were designed for the purpose

of this study. For the high involvement product category, the premium car manufacturer

BMW was chosen as a brand. The chocolate brand M&M was picked as low involve-

ment counterpart. For the non-meme variation of these brands previous official post-

ings were selected, which show only the product without any claim or text to ensure a

neutral basis. As memes contain verbal elements, the non-meme postings were added

with a text box including the products name. The pictures were then edited into a layout

which is based on Instagram’s typical layout. The top part shows the brand’s Instagram

account name. The bottom part shows the like, comment and share button. The num-

ber of likes were cut out, to prevent from its influence on the evaluation of the ad.

PraxisWISSEN Marketing

PraxisWISSEN Marketing 1/2023 DOI 10.15459/95451.59 S. 45

AfM

Arbeitsgemeinschaft

für Marketing

Fig. 1 Low involvement ad Fig. 2 High involvement ad

without meme without meme

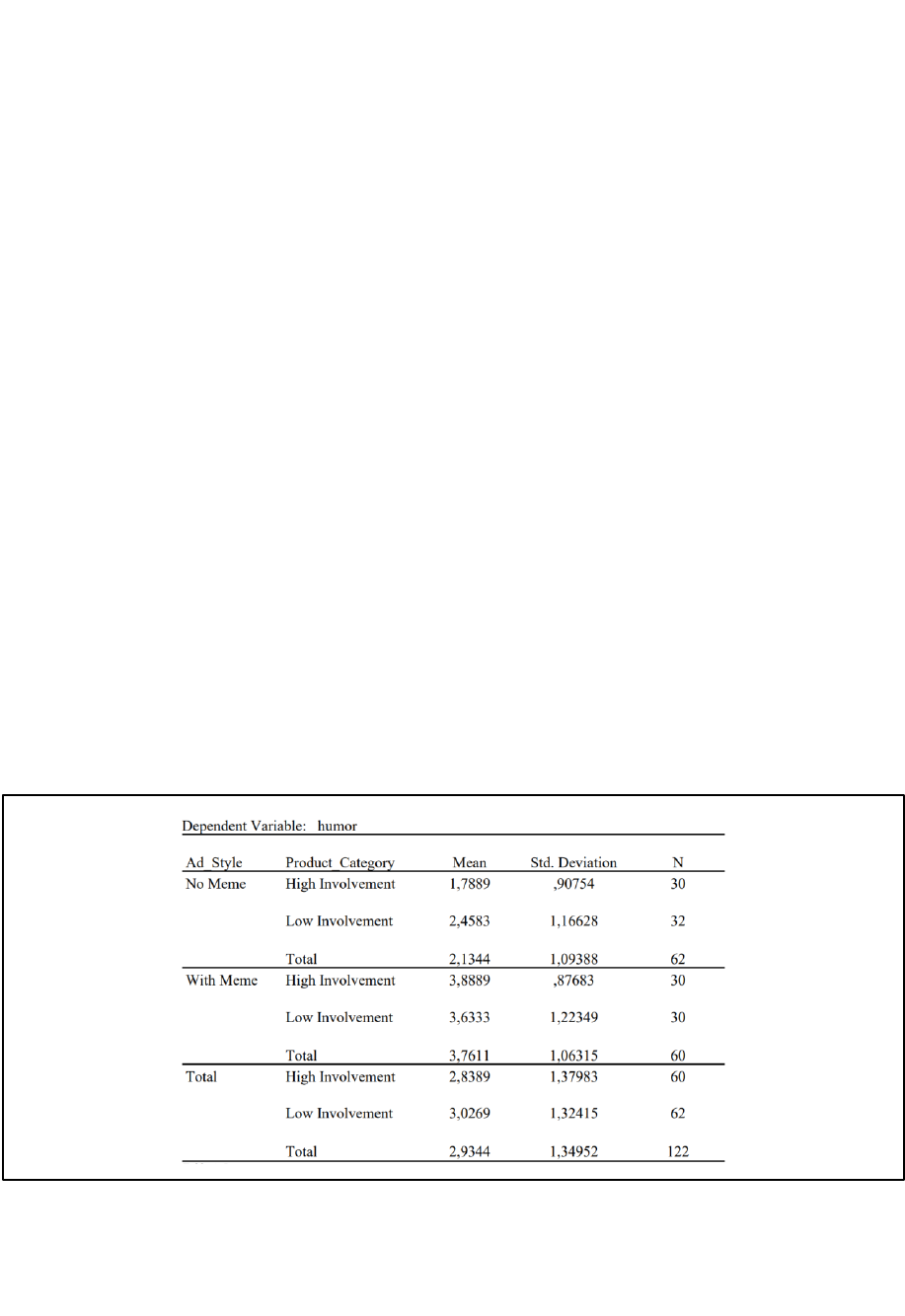

For the meme version of social media ads, eight different memes were created with

different meme formats and different jokes. In a pre-test with a small group of 12 par-

ticipants the funniest meme out of those options was chosen: The meme using a tux-

edo Winnie the Pooh format.

This meme is divided into two halves. The top part shows a bored looking Winnie the

Pooh having a text box right next to it. In this text box, a common expression for the

respective product is entered. The bottom part of the meme also shows Winnie the

Pooh but smiling and dressed in a tuxedo. Right next to it is also a text box, however

with a fancy and exaggerated expression for the same product. The humor in these

memes lies in the exaggeration and creative formulation in the bottom text box. Winnie

the Pooh in tuxedo implies that the exaggeration is an attempt to make the product

sound fancier and more sophisticated than it actually is.

For M&M (see figure 3) the top part says “Schokolinsen” (chocolate drops) and the

bottom part states “Bunte Perlen aus Vollmilchschokolade mit einer Erdnussfüllung”

(colorful pearls of milk chocolate with a peanut filling). For BMW (see figure 4) the top

text box says “Elektrofahrzeug” (electric vehicle) and the bottom part states “Vehikel

mit vollelektrischem Antrieb, 600 km Reichweite & intelligenter Software” (vehicle with

all-electric drive, 600 km range & intelligent software).

PraxisWISSEN Marketing

PraxisWISSEN Marketing 1/2023 DOI 10.15459/95451.59 S. 46

AfM

Arbeitsgemeinschaft

für Marketing

Fig. 3 Low involvement ad Fig. 4 High involvement ad

with meme with meme

(own creation) (own creation)

The online survey took place between February 16

th

, 2022, and March 15

th

, 2022. 122

participants were recruited for this study, with a median age of 26 years, ranging be-

tween 17 and 65 years. Out of the 122 participants, 55 (45.1%) were male and 67

(54.9%) females. 18.0% of the participants have a monthly net income of below 501 €,

23.0% earn between 501 and 1.500 €, 25.4% between 1.501 and 2.500 € and 33.6%

earn more 2.500 € per month.

The total sample was divided into four groups. Group one was shown the high involve-

ment brand posting without a meme. This group of 30 participants (10 males) has a

median age of 29.00 years. The second group was presented the meme posting of the

high involvement brand. This group consisted of 30 participants (16 males) with a me-

dian age of 24.00 years. The third group was shown the low involvement brand post

without a meme. Here, 32 participants (18 male) have a median age of 33.50 years.

The fourth group was exposed to the low involvement brand post with a meme. The

last group consisted of 30 people (11 male) with a median age of 25.50 years.

At the beginning of the survey, participants were informed about the background and

anonymity of the survey. Next, they were shown four social media posts from four dif-

ferent brands. In addition to BMW and M&M, Colgate and Bauknecht were featured.

On the next page the aided recall was tested, the participants were asked to choose

from a list of car brands (if BMW is to be rated) or candy brands (if M&Ms is to be rated)

the one that was seen before. After that, the participant was shown the target stimulus

material again.

PraxisWISSEN Marketing

PraxisWISSEN Marketing 1/2023 DOI 10.15459/95451.59 S. 47

AfM

Arbeitsgemeinschaft

für Marketing

To capture the non-observable states of the individual participants emotions, attitudes,

and evaluations, and to translate them into measurable variables, a five-point Likert

scale was used, which also allows participants to express their indifference. The fol-

lowing constructs and target variables were queried each with these three items:

• The attitude towards the ad

• The attitude towards the brand

• The participant’s purchase intention

• Involvement of the participant for memes

• Involvement of the participant for the product category

As this study features a 2x2 factorial between-subject design, a two-way ANOVA (ana-

lysis of variances test) was run to compare the means of dependent variables of the

four groups for significant differences. Assumptions for the ANOVA test are the homo-

geneity of variances, which were tested with the Levene’s test, and a normal distribu-

tion of the variables. Normal distribution was not tested in this study as the Central

Limit Theorem can be applied for all four groups. The assumption of equality of vari-

ances using the Levene’s test was also run for each independent variable.

To check whether meme postings were perceived as humorous, participants were

asked to rate the humor level of the posting. ANOVA was run to check if groups pre-

sented with memes perceived more humor than groups presented non meme ads.

Levene´s test supports the assumption of homogeneity of variances, F(3, 118) = 1.783,

p = .154. Descriptive statistics can be taken from figure 5. The results of the ANOVA

suggest that between no-meme version (M=2.1344) and meme version (M = 3.7611)

are significant differences in the perception of humor (F(1, 118) = 73.185, p < .001, 𝜂

2 = .383).

Fig. 5 Descriptive statistics humor

The meme versions of the social media postings, both in case of products with high

and low involvement, were able to convey significantly more humor than the ones

without memes.

PraxisWISSEN Marketing

PraxisWISSEN Marketing 1/2023 DOI 10.15459/95451.59 S. 48

AfM

Arbeitsgemeinschaft

für Marketing

3. Research results

3.1 Attitude towards the ad

A two-way ANOVA test was run to verify direct effects of the ad style (with or without

meme) and the product category (high or low involvement) on the attitude towards the

ad. Results of Levene’s test reveal that the assumption of homogeneity of variances is

given (F(3, 118) = 1.365, p = .257). Descriptive statistics are shown in figure 6 and

results of the ANOVA test in figure 7. No significant direct effects of the ad style (F[1,

118] = .210, p = .648, 𝜂 2= .002) and product category (F[1, 118] = 1.121, p = .292, 𝜂

2= .009) could be statistically proven. The results show no significant interaction effect

between the independent variables on the attitude towards the ad, F(1, 118) = 1.805,

p = .182, 𝜂 2 = .015. Hence hypothesis H1a, H1b and H1c are rejected.

Fig. 6 Descriptive statistics attitude towards the ad

Fig. 7 Between-subject-effects test attitude towards the ad

PraxisWISSEN Marketing

PraxisWISSEN Marketing 1/2023 DOI 10.15459/95451.59 S. 49

AfM

Arbeitsgemeinschaft

für Marketing

3.2 Attitude towards the brand

Levene´s test reveals homogeneity of variances, F(3, 118) = .267, p = .849. Descriptive

statistics are shown in figure 8. No significant effect of the ad style on the attitude

towards the brand could be proven, F(1, 118) = .131, p = .718, 𝜂 2 = .001. As well no

significant effect of the product category on the attitude towards the brand could be

proven, F(1, 118) = .011, p = .718, 𝜂 2 < .001, see figure 9. Hence there was no signif-

icant interaction effect between the ad style or the product category on the attitude

towards the brand visible, F(1, 118) = 1.578, p = .211, 𝜂 2 = .013. Hypothesis H2a, H2b

and H3c are rejected.

Fig. 8 Descriptive statistics attitude towards the brand

Fig. 9 Between-subject-effects test attitude towards the brand

PraxisWISSEN Marketing

PraxisWISSEN Marketing 1/2023 DOI 10.15459/95451.59 S. 50

AfM

Arbeitsgemeinschaft

für Marketing

3.3 Purchase intention

To analyse the direct effects of memes and the product category on the purchase in-

tention, a two-way ANOVA test was run. Respective descriptive statistics are pre-

sented in figure 10. Figure 11 shows the results of the ANOVA test. Levene’s test

indicates homogeneity of variances, F(3, 118) = 2.189, p = .093). The results of the

ANOVA test show that neither the ad style (F[1, 118] = .1.678, p = .198, 𝜂 2= .014) nor

the product category (F[1, 118] = 3.633, p = .059, 𝜂 2= .030) have significant effects

on the purchase intention. No significant interaction effects could be statistically proven

(F[1, 118] = 2.652, p = .106, 𝜂 2= .022). Hypothesis H3a, H3b and H3c are conse-

quently rejected.

Fig. 10 Descriptive statistics purchase intention

Fig. 11 Between-subject-effects test purchase intention

PraxisWISSEN Marketing

PraxisWISSEN Marketing 1/2023 DOI 10.15459/95451.59 S. 51

AfM

Arbeitsgemeinschaft

für Marketing

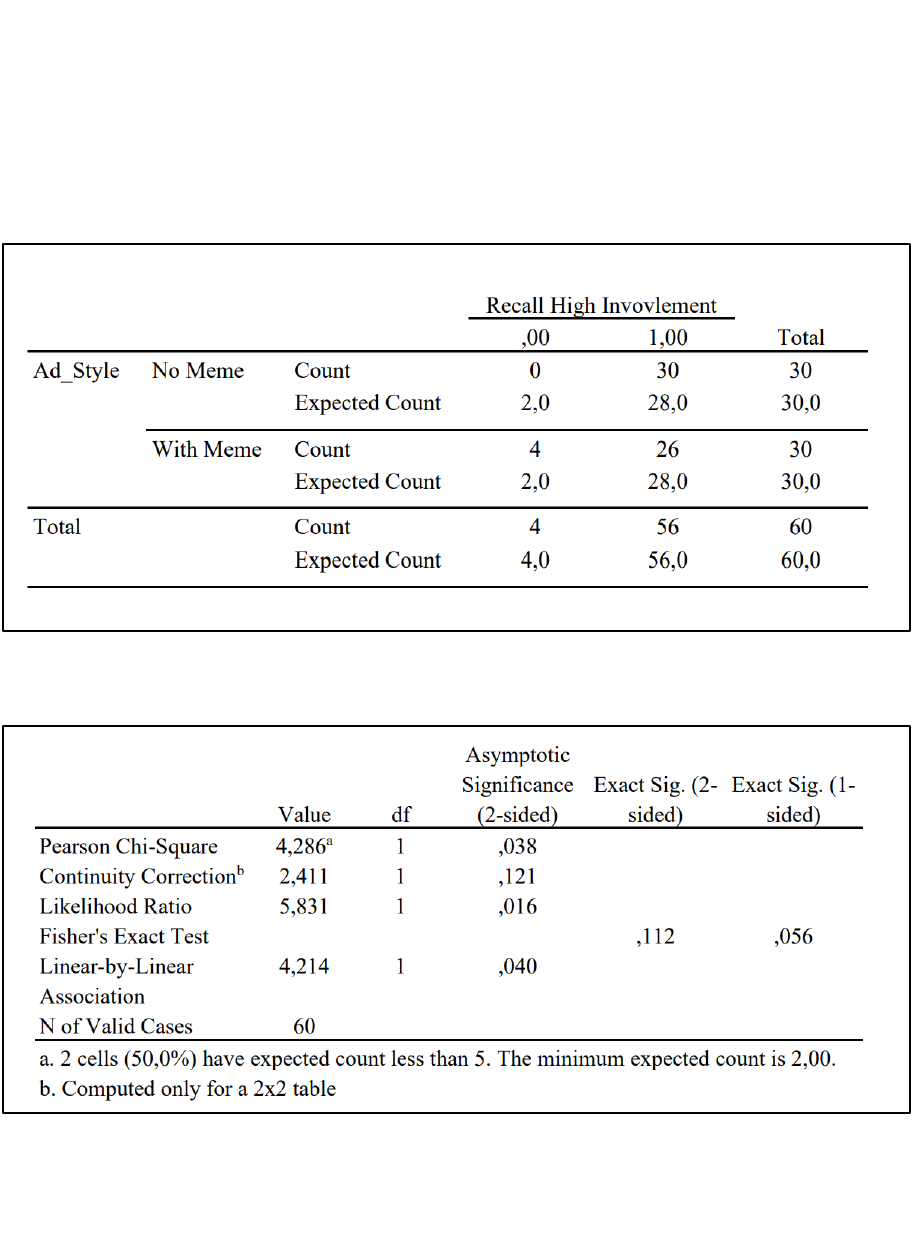

3.4 Brand recall

Recall answers were encoded into dummy variables, with value 1 representing the

relevant brand (BMW respectively M&M) and 0 any of the other choices. A chi-square

test was run to verify if recall capabilities were dependent on the style of the ad. The

relation between the ad style and the recall was significant in the case of the high

involvement product, χ2 (1, N = 60) = 4.286, p = .038. Hence it could be stated that

memes have a negative influence on the recall capabilities of high involvement product

categories.

Fig. 12 Crosstabulation recall high involvement

Fig. 13 Chi-square test recall high involvement

PraxisWISSEN Marketing

PraxisWISSEN Marketing 1/2023 DOI 10.15459/95451.59 S. 52

AfM

Arbeitsgemeinschaft

für Marketing

Another chi-square test was performed to test the relation between the ad style and

low involvement brands. The proportion of participants, who were able to recall the

correct brand name were significantly higher in the group with no memes, χ2 (1, N =

62) = 6.116, p = .014. Hypothesis H4 as a consequence is to be rejected.

Fig. 14 Crosstabulation recall low involvement

Fig. 15 Chi-square test recall low involvement

PraxisWISSEN Marketing

PraxisWISSEN Marketing 1/2023 DOI 10.15459/95451.59 S. 53

AfM

Arbeitsgemeinschaft

für Marketing

5. Limitations, conclusions, and recommenda-

tions

This study has several potential limitations that may affect the results. First, the crea-

tion of a theoretical framework was constrained by the lack of research on the promo-

tional effectiveness of memes in social media marketing. Second, the general validity

and representation of the study might be limited due to the usage of various diverse

reference groups. Third, creating ads with memes and ads without memes for two

product categories requires a different layout of the ads, which inevitably leads to sys-

tematic differences. However, the purpose of this study was to gain a better under-

standing of how memes in social media marketing for different product categories in-

fluence consumers' brand evaluation and purchase intentions.

Under the condition of these limitations, the results of this study indicate that memes

serve as a tool in advertising to convey humor. The study was able to reveal three main

findings.

First, memes have no significant effect on the attitude towards advertising, the attitude

towards the brand, and the purchase intention. Second, no significant differences could

be confirmed between product categories with high involvement and those with low

involvement when using memes in social media marketing. Third, memes seem to

have a negative impact on the brand recall.

To generalize, this study did not show evidence of improved advertising effectiveness

of ads with memes, in particular humor does not seem to be more effective in adver-

tising low-involvement products, as no differences were found between high and low

involvement products. Moreover, this study shows that the recall is negatively affected

by the presence of memes. As the sample included a wide variety of demographic

profiles, it is a good representation of the general population and therefore shows that

memes do not have a clear advantage in advertising effectiveness when targeting the

general population.

The results of this study provide several implications for practice: Brand and commu-

nication managers should not use memes in their social media marketing strategy

simply to follow trends. Memes are a form of humor and should therefore be carefully

planned so as not to offend anyone. Also, brands should be aware of who their target

audience is. If a brand has a younger target audience, it might be safe to assume that

their clientele also uses memes in their daily lives. Social media use is also dominated

by younger generations, and Internet memes are shared via social media, so it is rea-

sonable to assume that memes in this environment are more likely to be adopted by

young adults. Therefore, memes would be an appropriate way to fill the brand's social

media feed with content. However, there is no particular positive impact onto the con-

sumers’ attitude towards the ad or the brand to be expected. In fact, managers must

be aware of a possible negative impact onto the brand recall.

In future research, it would be valuable to extend existing findings by examining how

different age groups respond to memes. Further research is also needed to determine

under what circumstances memes could be an effective tool and under what circum-

stances they are not. Since there are many forms of memes and humor, different types

PraxisWISSEN Marketing

PraxisWISSEN Marketing 1/2023 DOI 10.15459/95451.59 S. 54

AfM

Arbeitsgemeinschaft

für Marketing

of humor should be researched to see if certain types of humor and memes have a

weaker respectively stronger effect. Future research could use other product catego-

ries, compare established brands with start-ups, and include services. In addition,

other metrics relevant to brands should be measured. For example, how memes in

marketing affect a brand's credibility, brand positioning, status, and trustworthiness

could be studied, especially in high involvement categories. Since research on memes

is still not extensive and memes are constantly evolving, there is still much research to

be done to better understand the advertising impact of memes.

References

Adam, A. (2021): Monkey puppet. Know Your Meme, https://knowyour-

meme.com/memes/monkey-puppet, retrieved December 6, 2021.

Almotairy, B.; Abdullah, M.; Abbasi, R. (2020): The impact of social media adoption on

entrepreneurial ecosystem, in: Tromp, J.G.; Le, D.-N.; Le,C.V. (eds.): Emerging Ex-

tended Reality Technologies for Industry 4.0: Early Experiences with Conception, De-

sign, Implementation, Evaluation and Deployment, pp. 63-79.

Blackmore, S.; Dugatkin, L. A.; Boyd, R;, Richerson, P. J.; Plotkin, H. (2000): The

power of memes. Scientific american, 283(4), pp. 64-73.

Bond, C. (2020). 5 of the Funniest, Millennial-Approved Brand Accounts on Twitter

(2020, May 01), https://www.wordstream.com/blog/ws/2018/06/29/funniest-twitter-ac-

counts, retrieved December 03, 2021.

Brubaker, P. J.; Church, S. H.; Hansen, J.; Pelham, S.; Ostler, A. (2018): One does

not simply meme about organizations: Exploring the content creation strategies of

user-generated memes on Imgur, in: Public Relations Review, 44(5), pp. 741-751.

Bury, B. (2016): Creative use of internet memes in advertising. World Scientific News,

p. 57.

Casey, A. (2018): The role of internet memes in shaping young people’s health-related

social media interactions, in: Young People, Social Media and Health, Routledge,

pp.15-30.

Chuah, K. M.; Kahar, Y. M.; Ch'ng, L. C. (2020): We “meme” business: Exploring Ma-

laysian Youth’ Interpretation of Internet Memes in social Media Marketing, in: Interna-

tional Journal of Business and Society, 21(2), pp. 931-944.

Conti, A. (2016): The Founder of Know Your Meme Explains What the Hell a Meme

Actually Is. VICE, https://www.vice.com/sv/article/7bxaeb/i-asked-the-founder-of-

know-your-meme-why-memes-are-funny, retrieved October 20, 2021.

Csordás, T.; Horváth, D.; Mitev, A.; Markos-Kujbus, É. (2017): User-Generated Inter-

net Memes as Advertising Vehicles: Visual Narratives as Special Consumer Infor-

mation Sources and Consumer Tribe Integrators, in: (Siegert, G.; von Rimscha, M.B.;

Grubenmann, S. (eds.): Commercial Communication in the Digital Age, Information or

Disinformation?, De Gruyter Saur, pp. 247-266.

PraxisWISSEN Marketing

PraxisWISSEN Marketing 1/2023 DOI 10.15459/95451.59 S. 55

AfM

Arbeitsgemeinschaft

für Marketing

Davison, P. (2012): The Language of Internet Memes, in: Mandiberg, M (ed.): The

social media reader, New York University Press, pp. 120-134.

Dynel, M. (2020): On being roasted, toasted and burned:(Meta) pragmatics of Wendy's

Twitter humour, in: Journal of Pragmatics, 166, pp.1-14.

Gleason, C.; Pavel, A.; Liu, X.; Carrington, P.; Chilton, L. B.; Bigham, J. P. (2019):

Making memes accessible, in: The 21st International ACM SIGACCESS Conference

on Computers and Accessibility, pp. 367-376.

Heylighen, F.; Chielens, K. (2009): Cultural evolution and memetics. Encyclopedia of

complexity and systems science, pp. 3205-3220.

Knobel, M. (2006): Memes and affinity spaces: Some implications for policy and digital

divides in education, in: E-Learning and Digital Media, 3(3), pp. 411-427.

Knobel, M.; Lankshear, C. (2007): Online memes, affinities, and cultural production, in:

Knobel, M.; Lankshear, C. (eds.): A new literacies sampler, Peter Lang Publishing, pp.

199-227.

Lintott, S. (2016): Superiority in humor theory, in: The Journal of Aesthetics and Art

Criticism, 74(4), pp. 347-358.

Murray, N.; Manrai, A.; Manrai, L. (2014): Memes, memetics and marketing: A state-

of-the-art review and a lifecycle model of meme management in advertising, in:

Moutinho, L.; Bingé, E.; Manrai, A.K. (eds.): The Routledge companion to the future of

marketing, pp. 366-382.

Osterroth, A. (2015): Das Internet-Meme als Sprache-Bild-Text, in: IMAGE. Zeitschrift

für interdisziplinäre Bildwissenschaft, 11(2), pp. 26-46.

Oxford Learner Dictionaries. (n.d.): Meme. Meme, https://www.oxfordlearnersdiction-

aries.com/definition/english/meme, retrieved October 5, 2022.

Petty, R. E.; Cacioppo, J. T. (1986): The Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion,

in: Advances in experimental social psychology, New York, Academic Press, Vol. 19,

pp. 123-205.

Shifman, L. (2013): Memes in a digital world: Reconciling with a conceptual trouble-

maker, in: Journal of computer-mediated communication, 18(3), pp. 362-377.

Shifman, L. (2014). Memes in digital culture. MIT Press.

Science Insider (2015, 28. October): Real Meaning Behind The Word „Meme“,

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6iHZi-z7H4o.

Zittrain, J. (2018): The future of the internet--and how to stop it. Yale University Press.

Wiggins, B. E. (2019): The discursive power of memes in digital culture: Ideology, se-

miotics, and intertextuality, New York.

Key words

Memes, humor, social media marketing, attitude, advertisement, brand, purchase

intention, brand recall

DIGITALE TRANSFORMATION • IMMERSIONDIGITALE TRANSFORMATION • IMMERSIONDIGITALE TRANSFORMATION • IMMERSION

EXPERIENCE • UX • MARKENIMAGEMESSUNGEXPERIENCE • UX • MARKENIMAGEMESSUNGEXPERIENCE • UX • MARKENIMAGEMESSUNG

METAVERSE • ADVERWORLDS • CORPORATEMETAVERSE • ADVERWORLDS • CORPORATEMETAVERSE • ADVERWORLDS • CORPORATE

VALUE • INFLUENCER MARKETING • MEMESVALUE • INFLUENCER MARKETING • MEMESVALUE • INFLUENCER MARKETING • MEMES

USER GENERATED CONTENT, • INTERAKTION USER GENERATED CONTENT, • INTERAKTION USER GENERATED CONTENT, • INTERAKTION

VIRTUAL REALITY, • ADVERGAMES • CONTENTVIRTUAL REALITY, • ADVERGAMES • CONTENTVIRTUAL REALITY, • ADVERGAMES • CONTENT

MARKETING • MARKTFORSCHUNG • SHAREDMARKETING • MARKTFORSCHUNG • SHAREDMARKETING • MARKTFORSCHUNG • SHARED

VALUE IMAGE • STAKEHOLDER VALUE • USER VALUE IMAGE • STAKEHOLDER VALUE • USER VALUE IMAGE • STAKEHOLDER VALUE • USER

ASSOZIATIVE MARKENNETZWERKE • HUMOR ASSOZIATIVE MARKENNETZWERKE • HUMOR ASSOZIATIVE MARKENNETZWERKE • HUMOR

SOCIAL MEDIA • MARKENWISSEN • MARKEN-SOCIAL MEDIA • MARKENWISSEN • MARKEN-SOCIAL MEDIA • MARKENWISSEN • MARKEN-

IMAGE • STORE-BRAND-IMAGE • TEXT-MININGIMAGE • STORE-BRAND-IMAGE • TEXT-MININGIMAGE • STORE-BRAND-IMAGE • TEXT-MINING

EINSTELLUNGEN • KUNDENZUFRIEDENHEIT EINSTELLUNGEN • KUNDENZUFRIEDENHEIT EINSTELLUNGEN • KUNDENZUFRIEDENHEIT

EINKAUFSSTÄTTENIMAGE • ADVERGAMESEINKAUFSSTÄTTENIMAGE • ADVERGAMESEINKAUFSSTÄTTENIMAGE • ADVERGAMES

UX • MARKENIMAGEMESSUNG • STAKEHOLDERUX • MARKENIMAGEMESSUNG • STAKEHOLDERUX • MARKENIMAGEMESSUNG • STAKEHOLDER

VALUE • MARKENIMAGE • VIRTUAL REALITYVALUE • MARKENIMAGE • VIRTUAL REALITYVALUE • MARKENIMAGE • VIRTUAL REALITY