NOVEMBER 2020

INSIDE FAMILY CHILD CARE

NETWORKS: SUPPORTING

QUALITY AND SUSTAINABILITY

Findings from The National Study of Family Child Care Networks, Case Studies

CASE STUDIES

RECOMMENDED CITATION:

Bromer, J., Ragonese-Barnes, M., & Porter, T. (2020). Inside family child care networks: Supporting quality and sustainability. Chicago, IL:

Herr Research Center, Erikson Institute.

The report is available to download at: https://www.erikson.edu/research/national-study-of-family-child-care-networks

For more information about this study, contact:

Juliet Bromer, Ph.D.

Herr Research Center

Erikson Institute 451 N. LaSalle Street, Chicago, IL 60654

Phone: (312) 893-7127 Email: jbromer@erikson.edu

3

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the network directors and sta who participated in these cases studies and to all of the family child care educators

who agreed to have observers in their homes and to talk with us about their experiences caring for children and families. Their

willingness to commit so much of their time and their candidness about sharing information were essential to this report.

We want to thank Jon Korfmacher, Associate Professor at Erikson Institute, for his expertise and guidance throughout the

design, data collection, analyses, and writing of this report.

In addition, Erikson Institute sta contributed to the study:

• Helen Jacobsen, Project Manager

• Cristina Gonzalez del Riego, former Research Analyst

• Jennifer Baquedano, Data Collector

• Tiany Gorman, Research Assistant

• Margaret Reardon, Administrative Coordinator

• Patricia Molloy, Project Manager

We are grateful to the Pritzker Children’s Initiative, a project of the J.B. and M.K. Pritzker Foundation for its support of this study.

The views expressed in this report do not reflect the foundation’s views or policies. They are ours alone.

JULIET BROMER

Research Scientist

HERR RESEARCH CENTER

ERIKSON INSTITUTE

TONI PORTER

Principal

EARLY CARE AND

EDUCATION CONSULTING

MARINA RAGONESE-BARNES

Research Analyst

HERR RESEARCH CENTER

ERIKSON INSTITUTE

PREFACE

The case studies described in this report were conducted prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Many of the findings focus on in-person

supports for family child care educators such as visits to homes and training sessions. While some of the recommended practices

that emerge from this report may not be feasible during the pandemic, we hope that findings can inform broader policy and program

decisions about the types of supports that family child care educators need and that are most likely to contribute to positive

outcomes for children and families.

4

INSIDE FAMILY CHILD CARE NETWORKS

Table 1.1 Child Care Assessment Tool for

Relatives (CCAT-R) constructs

overview

Table 2.1 Services oered at Little People

FCCN

Table 2.2 Little People FCCN Sample

Table 2.3 Characteristics of FCC educator

study sample at Little People

FCCN

Table 2.4 Educator motivations for doing

FCC at Little People FCCN

Table 2.5 Reasons educators participate in

Little People FCCN

Table 2.6 Characteristics of family child care

programs at Little People FCCN

Table 2.7 Enrollment in FCC homes at Little

People FCCN

Table 3.1 Services oered at Downtown

FCCN

Table 3.2 Downtown FCCN Sample

Table 3.3 Characteristics of FCC educator

study sample at Downtown FCCN

Table 3.4 Educator motivations for doing

FCC at Downtown FCCN

Table 3.5 Reasons educators participate in

Downtown FCCN

Table 3.6 Characteristics of family child care

programs at Downtown FCCN

Table 3.7 Enrollment in FCC homes at

Downtown FCCN

Box 2.1 Little People FCCN Mentoring

Program

FIGURES & TABLES

INSIDE FAMILY CHILD CARE NETWORKS:

SUPPORTING QUALITY AND SUSTAINABILITY

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1

INTRODUCTION & BACKGROUND

Research Questions 8

Road Map to the Report 8

I. CHAPTER 1:

RESEARCH DESIGN & METHODS

Recruitment 9

Protocols and Procedures 9

Sample 11

Data Analysis 11

II. CHAPTER 2: LITTLE PEOPLE

FAMILY CHILD CARE NETWORK 12

Characteristics of Network Sta, FCC Educators,

and Families Served 13

Approaches to Service Delivery 17

Supporting Quality 21

Supporting Sustainability of FCC Businesses 26

Sta Support and Supervision 31

III. CHAPTER 3: DOWNTOWN

FAMILY CHILD CARE NETWORK 32

Characteristics of Network Sta, FCC Educators,

and Families Served 33

Approaches to Service Delivery 37

Supporting Quality 42

Supporting Sustainability of FCC Businesses 47

Sta Support and Supervision 51

IV. CHAPTER 4: BENEFITS OF NETWORK

PARTICIPATION ACROSS BOTH SITES

Daily Support 52

Sense of Professionalism 53

V. DISCUSSION

Discussion and Summary of Findings 54

Limitations 56

VI. IMPLICATIONS FOR FUTURE PROGRAM

DEVELOPMENT AND RESEARCH

Implications for How Networks Can Support

FCC Quality Caregiving 57

Implications for How Networks Can Support

FCC Sustainability 58

Implications for Future Research 59

VII. REFERENCES 60

VIII. APPENDICES

Appendix A: Methods Supplemental Detail 63

Appendix B: Little People FCCN Tables 66

Appendix C: Downtown FCCN Tables 76

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1

INSIDE FAMILY CHILD CARE NETWORKS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Home-based child care (HBCC), non-parental care provided in the home of a regulated family child care educator (FCC) or an

unregulated family, friend, or neighbor caregiver (FFN), is the most common child care arrangement for children under age five in

the U.S. (National Survey of Early Care and Education [NSECE] Project Team 2015a). HBCC settings are more likely to serve infants,

toddlers, and children who live in poverty as well as families who need care outside of traditional hours (Laughlin, 2013; NSECE

Project Team, 2015b, 2013; Porter et al., 2010). The widespread use of HBCC has heightened concern about the quality of care that

these educators oer. At the same time, there is a documented decline of regulated FCC in the U.S. (NCECQA, 2020) which suggests

that sustainability of FCC settings as well as the quality of these settings are critical issues for this sector of the early childhood

workforce.

HBCC or FCC networks (FCCN) – organizations that deliver a combination of services over time with specialized sta whose primary

responsibility is working with HBCC providers – have emerged as a strategy for addressing these two broad issues (Bromer & Porter,

2019). The body of research on network eectiveness is limited. Only two studies have specifically examined eects on quality in

regulated FCC settings (Bromer et al., 2009; Porter & Reiman, 2016). Both found positive results: FCC educators who participated in

networks were more likely to provide higher quality care than those who did not.

This report presents findings from in-depth case studies of two FCC networks (FFCN) that serve regulated FCC educators – Little

People FCCN and Downtown FCCN . The study sought to understand approaches to service delivery implementation, the experiences

of educators who received network services and sta who delivered these services, and the relationship between network service

delivery and both quality caregiving and business sustainability in aliated FCC homes.

• In-depth interviews and surveys with FCCN sta oered a portrait of how services are delivered to FCC educators as well as

insights into the types of relationships that networks build with aliated FCC educators

• In-depth interviews and surveys with FCC educators oered insights into educator experiences oering child care and working

with a FCCN around quality and sustainability.

• Observations of quality in FCC homes oered data on caregiver-child interactions, materials available for learning, and health

and safety materials and practices in the home child care setting.

• Focus groups with parents of children enrolled in FCC homes shed light on how FCCNs interact with and support families.

A total of 105 FCC educators, 12 sta members, and 16 parents participated in the study across the two networks. Data were collected

in 2019 through in-person site visits, telephone interviews, surveys, and in-person observations.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

SNAPSHOT OF THE TWO NETWORKS

The two networks served dierent types of communities, children, families, and educators. They also operated in dierent state

policy contexts (see Appendix D for comparison tables).

• Little People FCCN was located in a suburban area and served mostly white, middle- and upper-class professional families

with infants and toddlers. Families paid private tuition to the network which paid the educators for their child care work.

More than half of the FCC educators who participated in the study self-identified as immigrants from Middle Eastern

and South Asian countries, and many reported that English was not their first language. More than half had a college or

post-graduate degree. Network supports included visits to FCC homes, training workshops, an apprenticeship program

to help new educators become licensed, help with administrative and business aspects of running a child care program,

and coaching for educators who participated in the state’s Quality Rating and Improvement System (QRIS). In addition to

network supports, Little People FCCN also served as a licensing agency, responsible for monitoring compliance with state

regulations.

• Downtown FCCN operated in a small city and served families, many living in poverty, who were eligible for child care

subsidies, were TANF priority populations, and received child welfare services. The majority of educators self-identified

as Latinx. Over two thirds had less than a college degree with most having a high school degree or GED as their highest

level of education. Downtown FCCN administered subsidy payments to FCC educators as part of a statewide infrastructure

of supports for FCC but was not responsible for monitoring compliance with state standards. The network oered

supports including twice-monthly visits to FCC homes, a training series for new providers, professional development, and

opportunities for community engagement. The network also had sta who oered family support services to parents of

children enrolled in aliated FCC homes.

KEY THEMES & FINDINGS

The ways that networks deliver supports may contribute to the quality of observed educator-child interactions and the child care

environment. Educators at both networks demonstrated high-quality engagement with children’s learning and learning materials.

There were dierences in the quality of nurturing practices. Downtown FCCN educators had lower ratings on nurturing practices,

with scores in the poor range, compared to Little People FCCN educators, whose nurturing practices with children were rated as

acceptable. Some of these dierences may reflect educators’ levels of education as well as variations in group sizes and ages of

children in care. On average, FCC homes aliated with Little People FCCN enrolled fewer and

younger children than FCC homes aliated with Downtown FCCN.

Dierences in quality scores may also be related to approaches to service delivery. The

vast majority of educators at Little People FCCN reported that specialist visits focused on

discussions about the children in their care, including child development, and the child care

environment. Visits at Downtown FCCN, by contrast, primarily focused on crisis management,

behavioral challenges of children in care, and personal needs of educators and families.

Downtown FCCN’s focus on challenges may have been a response to its population of children

and families, who experienced many stressors including poverty, trauma, and homelessness.

Network approaches to relationship-building may contribute to health and safety compliance in FCC homes. Educators at both

Little People FCCN and Downtown FCCN had high levels of compliance around health and safety practices overall. However, there

were dierences in the proportions of educators whose homes had red flag items (items that had the potential to cause serious

injury or death). Lower proportions of Little People educators (one third) did not meet red flag health and safety indicators

compared to two thirds of Downtown educators. The most common red flag items were lack of electrical outlet covers, gates on

stairs for mobile infants and toddlers, and accessible electrical cords.

These dierences may be related to the network monitoring and enforcement roles. As a licensing agency, Little People FCCN had

an intentional and frequent focus on monitoring, which may explain the educators’ high health and safety scores. On the other

hand, the surprise unannounced visits created tensions with some educators and may have worked against the predictability and

“If we know that a provider

is a struggling with doing

art with infants and

toddlers, we’re going to

plan a training on that.”

Little People FCCN Specialist

2

INSIDE FAMILY CHILD CARE NETWORKS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

consistency of visits that are essential elements of building strong relationships. By contrast, Downtown FCCN was not tasked with

this enforcement role, which may have resulted in less attention to health and safety checks and lower scores. Instead, Downtown

FCCN focused on building relationships with educators, which may have created tensions around giving dicult feedback about

potential health and safety violations.

Networks provided dierent kinds of support for participation in QRIS. Educators at Little

People FCCN received additional visits from a sta member whose primary responsibility

was supporting them in the state’s voluntary QRIS system. Educators reported that her

support helped them overcome initial fears about participating and made it easy to advance

to higher levels. Downtown FCCN child care specialists were expected to help educators,

who were automatically registered as Level 1 in the state’s QRIS, to move to higher levels,

and the training coordinator sometimes provided workshops on specific QRIS topics. Yet

few educators were willing to move beyond Level 1, and neither specialists nor educators

mentioned this support in the interviews.

Network business supports may contribute to the sustainability of FCC businesses. We found that dierences in the networks’

approaches to business support may have influenced the sustainability of FCC businesses. Little People FCCN oered parent

orientations about its child care services and lists of educators who might meet parent needs, but the network expected educators

to recruit families. By comparison, Downtown FCCN placed families with educators through its state contracts, and had specific sta

who helped with referral and enrollment.

These dierences may have aected FCC enrollment, which, in turn, may have contributed

to the income educators could earn from their child care businesses. A significant proportion

of Little People FCCN educators operated at less than full licensed capacity, which may have

meant less income. The relatively high fees paid by parents, however, may have compensated

for lower enrollment. Educators at Downtown FCCN, by contrast, were typically full, but the

state reimbursement rate was low, which may have presented challenges for educators with

limited financial resources.

Direct financial assistance may also help educators maintain sustainable businesses because

it can oset the often-limited income that FCC businesses generate. Both networks in our

study oered financial assistance to aliated educators. Little People FCCN absorbed the

cost of liability insurance for FCC educators and oered emergency funding to cover the cost

of substitutes if educators had to close their business. The network also facilitated access to

state-funded scholarships to complete college courses. Downtown FCCN provided no-default

loans of up to $5000 for program and home repairs. Like Little People, Downtown also

facilitated educators’ access to state grants for materials and scholarships for college courses,

a degree, or a Child Development Associate credential.

Culturally-responsive network supports may shape educator engagement in services. Some research suggests that culturally-

responsive service delivery may shape educator engagement and quality of care (Bromer & Korfmacher, 2017), although we do

not have evidence from this study about how this aspect of service delivery may have related to quality. Downtown FCCN had an

intentional approach to culturally-responsive support. There was a strong cultural match between sta and educators; all of the sta

“If there was not this training, I wouldn’t know anything, what’s going on, or the rules,

or the qualifications — what I need for myself, how to take care of the children, to

understand them, and to see also if there is something going on at their home, the way to

talk to them, the way to communicate with them.”

FCC Educator at Little People FCCN

“I will tell them that we all

need to keep up with our

professionalism…

this is not just simple

babysitting. We have a lot

of responsibilities here.”

Little People FCCN Specialist

“They taught you how

to build your business in

a way where you make

money, not lose money. For

example, if I make $400, I

can’t spend $500, it would

defeat the purpose. So, you

learn to budget and find

ways to make things work

for better profit.”

Educator at Downtown FCCN

3

INSIDE FAMILY CHILD CARE NETWORKS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

self-identified as women of color, consistent with the population of educators in the network. Educators reported positive relationships

with sta, including trust and respect, as well as comfort and communication. All sta indicated that they provided personal support to

educators.

By contrast, Little People FCCN’s approach was less intentional. Most of the sta at Little People FCCN were white women serving

educators who were mostly immigrants from the Middle East. Both specialists and educators reported that cultural and linguistic

dierences sometimes interfered with eective support.

"For 30 years, we have been creating strong relationships. Sometimes we feel like a family... When a

provider is going through something, they receive the aection and the support.

We feel like this is more deep than just work. It goes more deeply.”

Downtown FCCN Director

Network support for families of children in FCC homes diered across the two networks.

Another notable dierence between the two networks was the role of the network in

supporting parents and families of children enrolled in aliated FCC homes. Little People

FCCN’s referral service for families and processing of parent fees were helpful for families

seeking child care, but the majority of network sta and support services were targeted

towards FCC educators.

By contrast, Downtown FCCN delivered supports to both FCC educators and to families of

children in their programs. The network had specialized sta whose job was to support and

connect families in the subsidy and child welfare systems to resources, including a social

worker. Another core component of service delivery focused on families was provision of

transportation to and from child care.

Neither network oered consistent evidence-based supports such as curriculum help or comprehensive services for children.

We found similar gaps in evidence-based services across both networks. Neither network oered consistent curriculum support for

educators, which research indicates is a key feature of high-quality early care and education (Burchinal, 2018; NSECE, 2015b). Nor did

we find evidence of delivery of comprehensive supports including developmental screening and mental health consultation for FCC

educators such as those oered by FCCNs that operate within Head Start and Early Head Start programs.

Neither network oered consistent and intentional reflective supervision for sta. Neither network had a strong infrastructure for

reflective sta supervision, which is an essential component of sta support (Bromer & Korfmacher, 2017). None of the sta at the two

networks reported receiving intentional and regular opportunities to reflect on their work with educators and to think about strategies

for improvement.

“They are opening doors

for you that otherwise, you

would not have been able

to open. I learned so much

with these people, and to

do so many other things.”

Downtown FCCN Parent

4

INSIDE FAMILY CHILD CARE NETWORKS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

IMPLICATIONS FOR HOW NETWORKS CAN SUPPORT

FCC QUALITY CAREGIVING

• Help FCC educators with regular maintenance of health and safety practices.

Regardless of a network’s enforcement role, network visits to FCC homes can help educators develop strategies and routines

around maintenance of daily health and safety precautions and practices. Monitoring visits should help educators strategize

systems and procedures for maintaining safe environments.

• Increase access to high-quality materials for FCC homes including health and safety equipment and learning materials for

dierent age groups.

Networks should consider providing funding for educators to purchase health and safety equipment for their FCC programs

and developing lending libraries that allow access to materials such as puzzles, fine and large motor materials, and books for

dierent age groups of children in care.

• Partner with QRIS to oer support through trusted family child care specialists.

Networks may be well-positioned to oer targeted QRIS support around FCC participation in quality improvement. FCC

educators may be more likely to engage in QRIS if the help comes from a trusted network rather than a state specialist.

• Use culturally-sensitive practices to recruit, engage, and sustain FCC participation in networks and in quality improvement

activities.

Culturally-responsive network stang and approaches to supporting FCC educators may increase FCC engagement in network

services. Networks should consider hiring sta who reflect the racial, cultural, and linguistic backgrounds of educators and

families served. Materials and trainings should be oered in languages that are preferred by educators and families.

• Engage in relationship-based practices with FCC educators combined with high-quality early childhood content.

Network supports may be most likely to shift FCC educator practices with children when they are rooted in strong, trusting

relationships focused on how to translate child development content into evidence-based practices. Relationships without

content may not improve quality and content without strong relationships may not engage educators in processes of

improvement.

• Support families of children in FCC homes through specialized sta and comprehensive services.

Networks have the potential to support families as well as FCC educators. Supporting families requires additional stang and

referral resources including social work sta, transportation, food, and housing supports as well as access to health services for

children and families.

• Oer training, support, and supervision to network sta who work directly with FCC educators.

Sta training, support, and supervision are key components of creating a network culture that values the process of quality

improvement at all levels. Regular and intentional reflective supervision of all sta who work directly with FCC educators may

help sta increase culturally responsive interactions, improve the quality of support oered, and intensify their focus on quality

caregiving.

5

INSIDE FAMILY CHILD CARE NETWORKS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

IMPLICATIONS FOR HOW NETWORKS CAN SUPPORT

FCC SUSTAINABILITY

• Develop contracts with state subsidy systems to increase recruitment and enrollment of families in FCC homes.

Contracts allow networks to guarantee a designated number of slots for children in aliated FCC homes and to process parent

subsidy payments for FCC educators. Contracts may be one strategy for supporting full enrollment in FCC homes.

• Help FCC educators with required paperwork for licensing and subsidy participation.

Networks spend time helping educators with paperwork and other administrative tasks that licensing and subsidy systems

require including keeping track of enrollment, child health records, and professional development hours. Networks may address

barriers that educators face by translating materials into preferred languages of educators and families or oering computer

support for accessing online trainings and applications.

• Oer training on financial management and marketing strategies that go beyond recordkeeping and contracts with families.

Networks have the potential to help educators develop business skills and practices that are most likely to lead to sustainable

operations. Educators may need technical assistance around marketing and recruitment strategies as well as financial

management.

• Oer financial assistance for home repairs and other infrastructure supports needed in FCC homes as well as for professional

development.

FCC educators may need financial help to address the regular wear and tear on their homes that results from doing child care in

a home setting. FCC educators may also need direct financial help to enroll in credential and college courses.

• Facilitate formal peer support activities for FCC educators that support provider leadership and growth.

Formal peer support activities may lead to increased educator engagement in quality improvement as well as increased

ecacy and professionalism. Networks that work with FCC educators as equal partners have opportunities to develop

leadership in the field.

This case study contributes to the relatively small research base on how family child care networks support care and education for

young children in FCC homes. The study shows how networks oer educators consistent and reliable support for their daily work

with children and families. The study also highlights the ways that networks provide educators with a sense of professionalism

through opportunities for skill and knowledge enhancement, peer to peer support, and business development. This report lays the

groundwork for future research on network eectiveness. The current study suggests potential links between network practices and

quality, including educator-child interactions, health and safety practices, and the child care learning environment. The approaches

to network support described in these case studies may be the first step towards identifying models that can be replicated in

demonstration studies that examine a range of possible outcomes for participating educators, children, and families.

6

INSIDE FAMILY CHILD CARE NETWORKS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

7

INSIDE FAMILY CHILD CARE NETWORKS

INTRODUCTION

Home-based child care (HBCC), non-parental care provided in the home of a regulated licensed family child care provider (FCC) or

an unregulated family, friend, or neighbor caregiver (FFN), is the most common child care arrangement for children under five in the

U.S. There are far more infants and toddlers in these settings than in centers (National Survey of Early Care and Education [NSECE]

Project Team, 2013). Moreover, families of color, families living in poverty and those who in rural areas, and families who need child

care outside of traditional hours are more likely to use HBCC (Laughlin, 2013; NSECE Project Team, 2015a; Porter et al., 2010).

The widespread use of HBCC, especially for very young children who are at risk for poor outcomes, has heightened concern about the

quality of care that these providers oer. Research indicates that there is wide variation in HBCC quality as there is in centers (Bassok

et al., 2016), but studies consistently find that HBCC providers rate lower on global quality measures than centers (Porter et al., 2010).

There are also growing concerns about trends in the supply of HBCC, particularly FCC. Nearly one in two licensed FCC providers

left the field between 2008 and 2017 (National Center on Early Childhood Quality Assurance [NCECQA], 2020), and the number of

providers in the Child Care Development Fund subsidy system dropped by approximately the same percentage between FY 2011 and

FY2016 (Oce of Child Care, 2014; Oce of Child Care, 2019).

HBCC networks or FCC networks – organizations that deliver a combination of services over time with specialized sta whose

primary responsibility is working with HBCC providers – have emerged as a strategy for addressing the dual issues of quality and

supply (Bromer & Porter, 2019). The body of research on network eectiveness is limited. Only two studies have specifically examined

eects on quality (Bromer et al., 2009; Porter & Reiman, 2016). Both found positive results: FCC providers who participated in

networks were more likely to provide higher quality care than those who did not.

Other research points to the potential of the services that networks oer – visits to providers’ homes, training workshops, and peer

support – for improving provider and quality outcomes. These services may contribute to provider knowledge and support provider

emotional and psychological well-being which may be related to the quality of care provided (Bromer & Korfmacher, 2017; Forry

et al., 2013; Gray, 2015; Jeon et al., 2018; McCabe & Cochran, 2008; Porter et al., 2010; Porter & Reiman, 2016). Still other research

suggests that supports such as help with marketing to attract enrollment, collecting fees from parents, and budgeting and financial

management can enhance provider’s business skills and capacity to maintain sustainable programs (Etter & Cappizano, 2018; Stoney

& Blank, 2011; Zeng et al., 2020).

The ways in which services are implemented is another aspect of service delivery that may shape quality, provider, child, and family

outcomes. Implementation science suggests that factors such as fidelity to an existing model, frequency and dosage of services,

sta training, and organizational capacity and culture may all contribute to the quality of support services (Bromer & Korfmacher,

2017; Paulsell et al., 2010). Research from related fields such as home visiting suggests that programs that adhere to a theory of

change model, oer intensive service delivery by well-trained and prepared sta, use a relationship-based approach to services,

and match the needs and interests of those served (families or providers) are most likely to produce positive outcomes (Bromer &

Korfmacher, 2017).

The current study is the third in a suite of reports from Erikson Institute’s National Study of Family Child Care Networks. Initiated in

2017, the National Study consisted of three components: 1) a survey of networks across the U.S. to document the network landscape;

2) qualitative interviews with a sub-sample of network directors to examine implementation of services; and 3) in-depth case studies

of two networks to understand how networks deliver services and the relationship between service delivery and quality of caregiving

among aliated providers. The first report, Mapping the Landscape of Family Child care Networks (Bromer & Porter, 2019), based on

a survey sample of 156 organizations that were broadly defined as networks, provided insights into the kinds of organizations that

operate networks and the services they provide. The second report, Delivering Services to Meet the Needs of Home-based Child Care

Providers (Porter & Bromer, 2020), which was based on in-depth interviews with a sub-sample of 47 network directors, examined the

fit between perceived provider challenges and needs, including licensing, subsidy, and quality rating and improvement system (QRIS)

demands, and network supports that are most likely to shape provider, child, and family outcomes.

INTRODUCTION

& BACKGROUND

This report presents findings from in-depth case studies of two family child care networks (FCCNs). Findings are based on surveys

and interviews with family child care educators

1

and network sta specialists at the two networks that sought to better understand

how networks approach and deliver services as well as the relationships between educators and sta that may influence the

eectiveness of service delivery. It also includes observations of caregiver-child interactions and child care environments to examine

possible associations with network characteristics and quality.

We aimed to address several broad questions in these case studies:

• What types of support services do the networks oer and what are the experiences of educators who

receive these supports?

• How do the networks approach service delivery implementation and what are the experiences of sta

who deliver services to educators?

• How do educators and sta perceive the quality of sta-educator relationships?

• What is the observed quality of caregiver-child interactions among aliated family child care educators

at each network?

• What is the relationship between support services and caregiving quality?

• Which services have the greatest potential for quality improvement and business sustainability?

RESEARCH QUESTIONS

ROAD MAP TO THE REPORT

The report is divided into five chapters. Chapter I describes our data collection process and analysis including measures and sample

description. Chapters II and III present findings from each of the case studies. Each includes detailed descriptions of the educator and

sta characteristics, educator participation and engagement in services, network supports for improving quality and sustainability,

approaches to service delivery, sta-educator relationships, and results of the caregiving quality observations. Chapter IV compares

findings from the two case studies, examining the strengths and weaknesses of each network and their potential for influencing

quality and sustainability of family child care. The report concludes with implications for program and policy development.

1 Throughout this report, we use the term “educator” to describe family child care providers, not only because it more closely captures the

essential role that these individuals play in the lives of children, but also because it is the way that providers have come to see themselves. We

only use “provider” in the direct quotes from educators or sta.

8

INSIDE FAMILY CHILD CARE NETWORKS

INTRODUCTION

CHAPTER I.

RESEARCH DESIGN & METHODS

We used a multi-site case study approach (Creswell, 2013) to examine two approaches to operating a family child care network. The

case study method allowed us to gather data from multiple sources within each network and to view educators’ experiences within

each of these network contexts. It also oered an opportunity to take a more in-depth look at how network services are implemented

and the experiences of participants within the network setting. The multi-site context allowed us to compare services, approaches,

and experiences across the two networks.

RECRUITMENT

We used several criteria to select the two networks for the case studies. One criterion was longevity, because we sought to examine

service delivery and approaches that organizations had consistently implemented over time. Another was the number of educators

served, because we needed a large enough sample to collect meaningful data on educators and sta as well as observed quality.

A third criterion was the community contexts in which the networks operated, because we aimed to better understand possible

dierences between networks that served families with dierent socio-economic characteristics.

In fall 2018 we invited Little People Family Child Care Network (Little People FCCN) and Downtown Family Child Care Network

(Downtown FCCN) to participate in the study.

1

Each met the criteria for a network: “an organization that oers HBCC providers

a menu of quality improvement services and supports including technical assistance, training, and/or peer support delivered by

a paid sta member” (Bromer & Porter, 2019, p.1). In addition, each organization was a stand-alone network that supported only

HBCC providers, unlike other networks that may be housed in umbrella organizations and also support center-based programs.

The research team had previous relationships with both networks, who had participated in prior research projects including the

National Study of Family Child Care Networks. Both networks were long standing organizations that had not engaged in any formal

evaluations.

The two sites were ideal for a case study approach. Each operated in a dierent policy context and served dierent populations of

children and families. Little People FCCN primarily served middle-income families and only accepted private pay for child care, while

Downtown FCCN primarily served low-income families who used a child care subsidy. The directors and sta at the networks helped

recruit sta, educators, and parents through emails, phone calls, and fliers for each activity in the case study research.

PROTOCOLS AND PROCEDURES

Data collection took place in spring and summer 2019. We used four data collection approaches in the case studies: 1) surveys of sta

and educators; 2) interviews with sta, educators, and directors; 3) focus groups with parents; and 4) observations of educators’

caregiving quality. The study received approval from Erikson Institute’s IRB. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior

to data collection.

SURVEYS

Two surveys were developed for this study to assess sta and educator experiences. The Sta Experiences Survey assessed sta

experiences delivering services, their perceptions of relationships with educators, and experiences of support and supervision at

the network and perceptions of organizational culture. Organizational culture includes psychological safety, which covers how

comfortable sta feel taking risks, making mistakes, and asking for support, which research shows is related to eective job

performance in other employment contexts (Edmondson, 1999). The Educator Experiences Survey assessed educator interest and

investment in network services, sta-educator relationship formation and development, and educators’ level of engagement and

comfort (or “fit”) with services received. The sta-educator relationships component of both surveys used the Relationship-Based

Support for Home-Based Child Care Assessment Tool (RBS-HBCC: Bromer, Ragonese-Barnes, et al., 2020) which examines emotional

connection, goal setting and collaboration, and responsiveness within these professional relationships.

1 We have changed the names of the networks to protect their confidentiality.

INSIDE FAMILY CHILD CARE NETWORKS

9

CHAPTER I

Online surveys were sent to sta specialists who worked directly with educators and to all educators at each network. Surveys were

also available in hard copy for educators or sta who preferred that format. All educator surveys were available in English or Spanish.

Educators and sta who completed the surveys were eligible to participate in a rae for a $50 gift card.

INTERVIEWS

During spring 2019 we conducted hour-long telephone interviews with a sub-sample of FCC educators who were aliated with each

of the networks and who responded to our survey. The educator interview was designed to learn about their experiences doing

family child care, their experiences with the network services, and the relationships they had formed with network sta. All interviews

with educators were conducted in English or Spanish. All interview participants received a $50 gift card for their participation.

We also conducted interviews with sta who worked directly with educators at both networks during site visits. Sta interviews

focused on the requirements of the sta’s job role, their experiences working at the network, and the relationships they formed with

FCC educators. Sta received a $25 gift card for their participation.

Two interviews were conducted with network directors. The initial interview, which was scheduled at the beginning of the study,

focused on the network’s mission and services. Follow-up interviews were conducted after the case study site visits and were

intended to clarify answers to questions that emerged from the site visit data collection.

At Downtown FCCN we interviewed community partners including the director of a local housing agency and a public school social

worker who had long-term partnerships with the network around serving the tightknit “Downtown” community. The interviews

focused on partners’ perceptions of the network’s role in the local community.

FOCUS GROUPS

We conducted focus group discussions with parents at each network site in English and Spanish. The parent focus group protocol

focused on parents’ experiences using FCC and their reasons for choosing their educator as well as their interactions with the

network and their perceptions of network support. Parents were recruited through network sta. The two-hour discussions were

conducted in English and Spanish. Parents received a $25 gift card for their participation.

QUALITY OBSERVATIONS IN FCC HOMES

We used the Child Care Assessment Tool for Relatives (CCAT-R: Porter et al., 2006; 2007), an observational instrument designed

to assess quality in HBCC settings. Originally intended to measure quality in relative child care settings, the CCAT-R has been

used in several evaluations of HBCC, including family child care educators (Forry et al., 2011). Unlike global quality measures such

as the Family Child Care Environment Rating Scales (FCCERS: Harms et al., 2007), the CCAT-R focuses on interactions around

communication and engagement between the educator and a single focal child. Four types of educator-child interactions are

assessed: Caregiver Nurturing, Caregiver Engagement, Bidirectional Communication, and Unidirectional Communication (see Table 1.1

and Appendix A for definitions). In order to understand quality in a mixed-age group of children in FCC settings, we chose to observe

the quality of educator-child interactions with two focal children – the oldest closest to age 5 and the youngest in the setting. The

CCAT-R uses time sampling to capture the frequency of educator-child interactions in timed cycles during a two-hour in-person

observation. In addition, the CCAT-R includes a Health and Safety Checklist that assesses health and safety practices and equipment,

including the presence of “red flag” items that could cause death or serious injury to children in care. The Materials Checklist assesses

the availability (not quantity) of materials in the child care home.

INSIDE FAMILY CHILD CARE NETWORKS

10

CHAPTER I

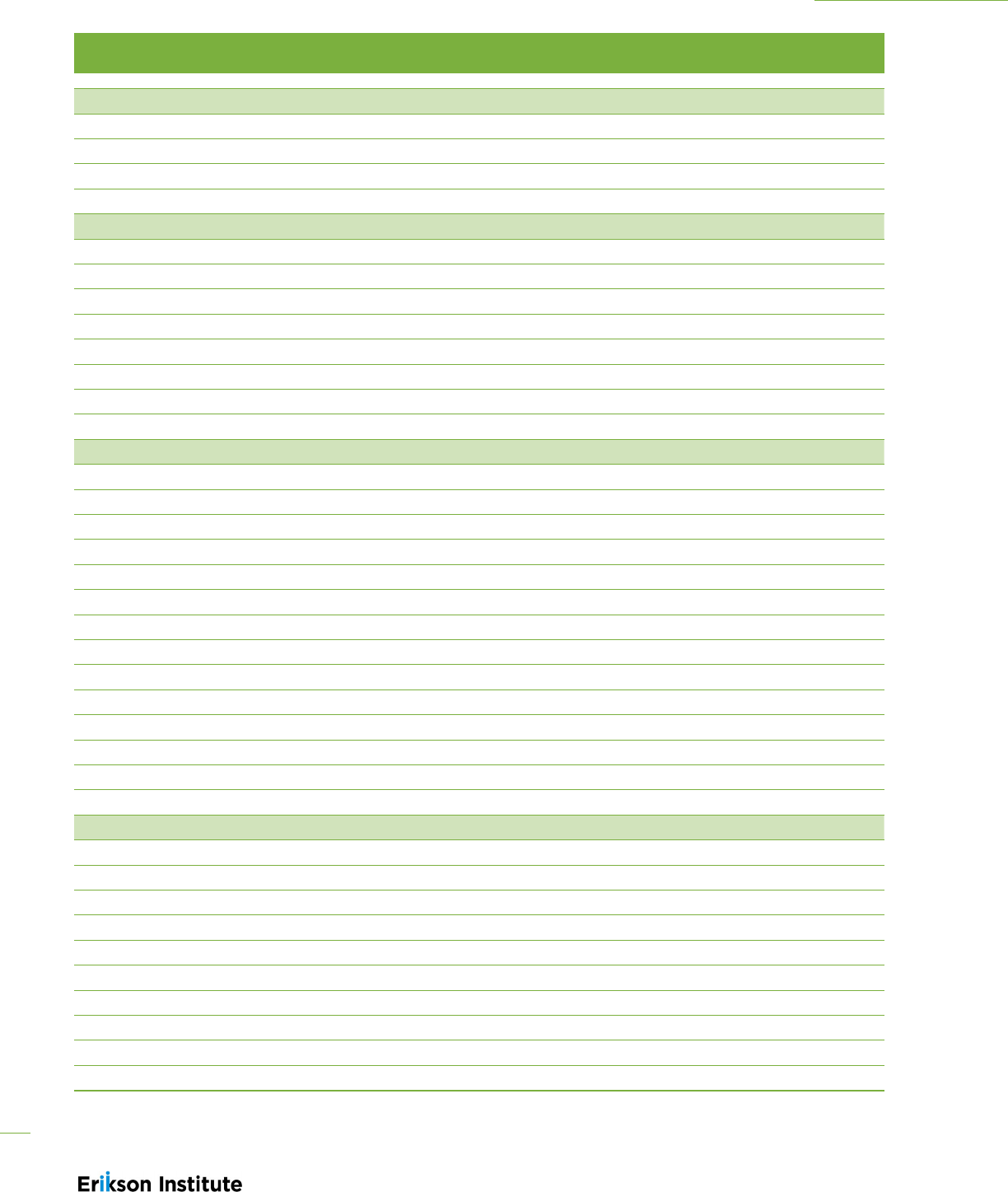

TABLE 1.1 CHILD CARE ASSESSMENT TOOL FOR RELATIVES

(CCAT-R) CAREGIVER-CHILD INTERACTIONS CONSTRUCTS OVERVIEW

Caregiver Nurturing

Measures the caregiver's support for social/emotional

development

Caregiver Engagement in Activity with Focus Child

Measures interactions that promote cognitive and physical

development

Caregiver/Child Bidirectional Communication

Measures interactions around language between the caregiver

and the child (i.e. reciprocal interactions), which supports

language and social/emotional development

Caregiver Unidirectional Communication with Focus Child

Measures the caregiver’s talk to the child, which supports

language development

Educators were asked in the interview if they were interested in participating in an observation. We also recruited educators for the

observations through their child care specialists. Some educators who had not completed the online Educator Experiences Survey or

the telephone interview participated in the observations and completed a short demographic survey that was administered during

the observation visit. Each educator received a $100 gift card as an incentive for participation in the observation.

SAMPLE

Detailed sample descriptions for each network site are described in the case study descriptions below and in Appendix A. A total

of 105 educators participated in at least one study activity. Nearly all network sta who worked directly with FCC educators at both

networks responded to the Sta Experiences Survey and participated in the interviews. Half of the educators at each network

(50% at Little People FCCN and 48% at Downtown FCCN)--responded to the survey. Survey respondents were not necessarily

representative of educators at the networks as the survey was sent to every educator and was not designed to gather representative

data. Additional educators who participated only in the observations completed a short demographic survey. Approximately 10

educators at each site participated in interviews. For Downtown FCCN, we also interviewed three community partners from local

organizations and agencies.

DATA ANALYSIS

Audio recordings of interviews and focus groups were transcribed and transcripts were coded with NVIVO 10 qualitative analysis

software. Codes were developed based on interview protocol questions and broad themes identified by the research team after initial

review of the transcripts and memos. We initially used the same codes across data from both network sites. Emergent codes that

were specific to each site were developed in subsequent rounds of coding. Inter-rater reliability of .80 was achieved for all coding.

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all survey and observational data. (See Appendix A for more detail.)

We used constant comparative analysis and triangulation across multiple data sources to identify emerging themes about educator

experiences with network supports and the connections between educator-sta relationships, quality caregiving, and support

services (Charmaz, 2006; Glaser, 1992; Strauss & Corbin, 1994). Our case study approach, in which all data collection took place within

two network sites, allowed us to view educator experiences and support processes at a micro-level both within each network and

across both networks.

INSIDE FAMILY CHILD CARE NETWORKS

11

CHAPTER I

CHAPTER II.

LITTLE PEOPLE

FAMILY CHILD CARE NETWORK

Little People FCCN was founded in 1983 to help parents who were attending a local college find child care. Today it identifies as a

shared service alliance, defined as an agency that helps child care programs with back-oce, administrative and business supports.

Little People serves several suburban communities in a metropolitan area. The network’s mission is to support the emotional, social,

and intellectual development of young children in high-quality FCC homes.

The network currently serves 92 FCC educators who are approved under state licensing and provides a range of services including

visits to educator homes, training, peer support, business support and financial aid (Table 2.1). It is also a state licensing agency and

performs regulatory functions around monitoring and compliance. Families who engage with the network for child care services do

not qualify for child care subsidies and pay privately for child care. Most of the network’s revenue comes from a percentage of

parent fees.

Five sta specialists worked directly with caseloads of 17 to 24 educators. Four child care specialists were responsible for conducting

licensing and monthly visits, and one quality specialist supported educators who participated in the state’s QRIS, as well as the

federal Child and Adult Care Food Program (CACFP). In addition to these five specialists, a workforce development coordinator was

responsible for onboarding new educators, including orientation visits and trainings at the network.

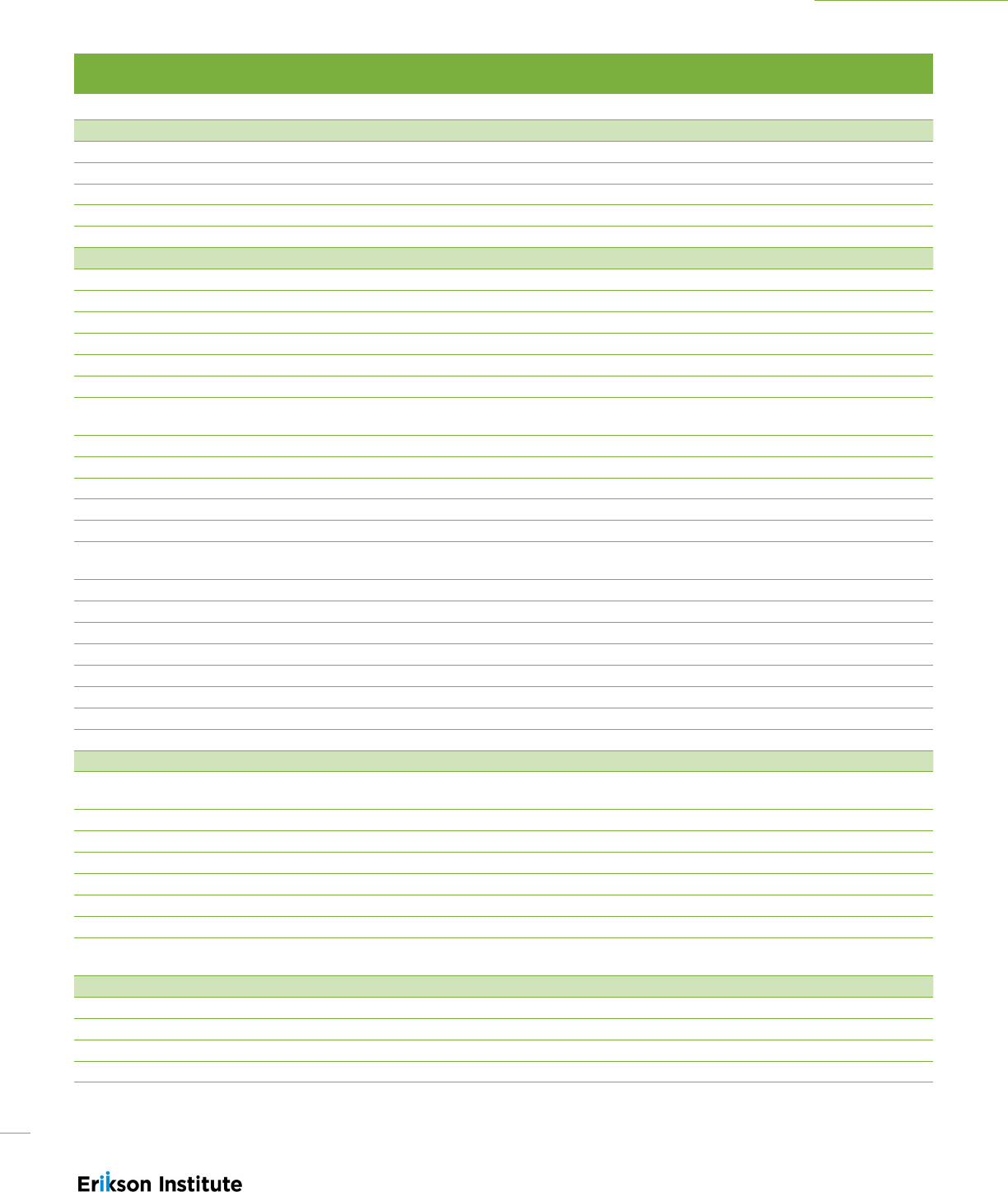

TABLE 2.1 SERVICES OFFERED AT LITTLE PEOPLE FCCN

Visits to Educators’ Homes Monthly visits; Annual safety inspection visit; 3 CACFP visits annually; QRIS coaching and visits

Training Workshops or workshop series in evenings or weekends (English only)

Peer Support 40-hour peer-to-peer mentoring by a mentor prior to opening their FCC home, occasional

mentoring afterwards; Provider Appreciation event; annual international potluck; networking at

trainings

Business Support Referrals for parents; invoicing of parent fees, payments to educators; training workshops on

business management, marketing, and tax preparation; substitute pool

CACFP Yes

Financial Support Support with accessing public scholarships or grants for continued education; emergency fund

for educators

Other Resources/Supports Medication administration and health training provided by outside partners

12

INSIDE FAMILY CHILD CARE NETWORKS

CHAPTER II

CHARACTERISTICS OF NETWORK STAFF,

FCC EDUCATORS, AND FAMILIES SERVED

The following section draws on survey and interview data from network sta and aliated educators. Table 2.2 shows an overview of

the study sample of sta, educators, and families at Little People FCCN.

TABLE 2.2

LITTLE PEOPLE FCCN SAMPLE

Participants

in study

Total sta 6

Sta experiences survey 6

Sta interview 6

Total educators 58

Educator experiences survey 46

Educator demographic survey only 12

Educator interview

1

12

Educator quality observations

2

26

Total family members 4

Parent focus group 4

1

The educator interviews are a subsample of the total survey sample;

2

12 educators who participated in quality observations only completed

an abbreviated demographic survey

STAFF CHARACTERISTICS

The five sta specialists and workforce development coordinator ranged in age from 40 to 67 at the time of our interviews (Appendix

B, Table B.1). Four self-identified as white, one as Latinx, and the other as Asian or Pacific Islander. Two specialists had prior

experience as FCC educators and others had experience teaching preschool or a background in social work. All sta members had a

college degree or higher.

13

INSIDE FAMILY CHILD CARE NETWORKS

CHAPTER II

FCC EDUCATOR CHARACTERISTICS

A total of 58 FCC educators participated in the study. More than half of the educators identified as Asian or Pacific Islander and many

were recent immigrants (Table 2.3). They ranged in age from 24 to 70. In the state, child care educators are required to be proficient

in English, but the first language of educators varied and included Spanish, English, Urdu, Punjabi, Farsi, Hindi, and Arabic.

Just over one third of educators had 11 to 20 years of experience, and an additional fifth had more than 20 years of experience. Close

to half (47%) had worked with the network for more than 10 years. Just under one half (47%) reported a college or post-graduate

degree, and a quarter had some college level coursework. Only 12% of educators reported significant economic hardship with most

reporting some diculty living on their household incomes. See Appendix B, Table B.2 for characteristics of educators by study

component.

TABLE 2.3

CHARACTERISTICS OF FCC EDUCATOR STUDY SAMPLE AT LITTLE PEOPLE FCCN

Full Sample Full Sample

%

(N)

%

(N)

Gender

1

Years as a family child care educator

1

Female 100% (54) Less than 2 years 4% (2)

Race/Ethnicity

2

2-5 years 15% (8)

Black or African American 6% (3) 6-10 years 26% (14)

White 13% (7) 11-20 years 35% (19)

Hispanic origin or Latinx 13% (7) More than 20 years 20% (11)

Asian or Pacific Islander 68% (36) Time spent with network

2

Highest level of education

2

6 months to 1 year 6% (3)

High school diploma/GED or Less 26% (14) 1-3 years 13% (7)

Some college, no degree 26% (14) 4-10 years 34% (18)

Associate's degree 15% (8) More than 10 years 47% (25)

Bachelor's degree 23% (12) Other paid jobs

6

Graduate degree 9% (5) Has another paid job 2% (1)

College or graduate level coursework

3

Does not have another paid job 98% (50)

Child development or early childhood education 77% (30) Diculty level living on household income

6

Psychology 18% (7) Not at all dicult 18% (9)

Business or administration 10% (4) A little dicult 41% (21)

Elementary education 10% (4) Somewhat dicult 29% (15)

Social work 5% (2) Very dicult 8% (4)

Nursing 8% (3) Extremely dicult 4% (2)

None 15% (6)

Child development associate credential (CDA)*

4

Mean Range

Has CDA 40% (17) Educator age (estimated from birth year)

7

Does not have CDA 60% (25) 51.16 24-70

Educator preferred language*

5

English only 60% (27)

Educator Experiences Survey and demographic survey (N=58);

N=54; N=53; Out of educators who answered having completed

at least some college for highest level of education (N=39); N=42;

N=45; N=51; N=49; *Question not asked in demographic survey, all

data comes from Educator Experiences Survey sample (N=46)

English and one or more language 24% (11)

Other language only 16% (7)

14

INSIDE FAMILY CHILD CARE NETWORKS

CHAPTER II

FCC educator motivations. A third of educators at Little People FCCN who responded to the Educator Experiences Survey reported

wanting to do FCC in order to stay at home with their own children (Table 2.4). Another third reported that FCC was a personal

calling for them and a quarter reported wanting to help children as a primary motivation. A majority reported wanting to continue

FCC work as long as they

were able.

TABLE 2.4 EDUCATOR MOTIVATIONS FOR DOING FCC AT LITTLE PEOPLE FCCN

% (N)

Primary reason for doing work

To have a job that lets me work at home 33% (14)

It is my personal calling or career 31% (13)

To help children 24% (10)

It is a step toward a related career 5% (2)

To help children's parents 5% (2)

To earn money 2% (1)

Number of years intends to be an educator

One more year or less 0% (0)

Two to five more years 7% (3)

As long as I am able 79% (33)

Not sure 14% (6)

Sample: Educator Experiences Survey (N=46); N=42

Reasons for joining the network. The primary reason educators reported for joining the network was to improve the quality of care

they oered children (Table 2.5). Just over half of educators who completed the survey reported wanting help working with parents

and families and/or help managing a business and slightly more than a third reported wanting help with enrollment of children or

having opportunities to meet other FCC educators.

TABLE 2.5 REASONS EDUCATORS PARTICIPATE IN LITTLE PEOPLE FCCN

% (N)

Learn how to improve quality of care for children 83% (38)

Get help working with parents and families 54% (25)

Get help with managing business 52% (24)

Increase enrollment or number of children in my care 37% (17)

Meet other educators 35% (16)

Obtain materials and equipment for my child care 26% (12)

Sample: Educator Experiences Survey (N=46)

15

INSIDE FAMILY CHILD CARE NETWORKS

CHAPTER II

Two of the 12 educators who participated in the interviews explained that the network provided supports that they had not received

elsewhere:

"I went there [to the County] and I took orientation

class and everything, but it looks still hard for me.

Then my friends told me that what [Little People

FCCN] provides--everything is in your home every

paper in your home. You just have to read it and

sign, so it looks better or easiest to me that I think I

have to join [Little People FCCN].”

“When I worked, too, in [the County], it

is hard to get the families, but for [Little

People FCCN], it is easy. They bring family

to us. They just email to parents, and parent

email to us, so it is easy to find a family… In

[the County], we have to advertise, and it is

hard to get the kids.”

FCC PROGRAM CHARACTERISTICS

Educators at Little People FCCN primarily cared for infants and toddlers (Table 2.6). Approximately 80% reported caring for toddlers,

and two thirds for infants. By contrast, fewer than a third provided care for preschoolers, and only one educator in our study oered

care to a school-age child. On average, educators cared for four children, although close to a third had an assistant. FCC hours of

operation were mostly during standard hours as well as early morning hours. Fewer reported oering evening, overnight, or

weekend care.

Little People FCCN serves private paying families. All educators who worked with the network operated under the network’s infant

toddler state license. About 30% reported participation in the state’s QRIS.

TABLE 2.6 CHARACTERISTICS OF FAMILY CHILD CARE PROGRAMS

AT LITTLE PEOPLE FCCN

% (N)

Age groups

Infants (0-12 months) 64% (29)

Toddlers (13-36 months) 80% (36)

Preschoolers (3-5 years old, not in kindergarten) 31% (14)

School-agers, 5 years and older 2% (1)

Nonstandard hours of operations

Oers evening, overnight, or weekend care 13% (6)

Does not oer evening, overnight, or weekend care 87% (40)

Has an assistant

29% (13)

Participates in the state's QRIS

30% (14)

Number of children Mean Range

3.58 0-6

Sample: Educator Experiences Survey (N=46) ); N=45; N=43

16

INSIDE FAMILY CHILD CARE NETWORKS

CHAPTER II

FCC environments. Little People FCCN operates in a suburban metropolitan area. Housing stock consists of multi-story town houses,

apartments, and single-family homes. Many of the educators live in town houses. The 12 educators who participated in interviews

were asked to describe their child care environments. Six educators described using their whole homes for child care, as the following

educator described:

• “I kind of use almost everywhere because I use my living room for almost all of it. I have my couch, my dining room... when

[the children] are here, we use the whole thing all the way, the whole place, and then the bedrooms I use them for nap time. I

have cribs in there and … we use them for nap time. It’s like the whole thing is for business. Only evening time that it’s home.”

Five educators used a separate space such as a basement for child care. One educator described the advantage of having her child

care program separate from her family’s space:

• “It's a big, big room… I had one bathroom for them and one small kitchen. I put refrigerator and microwave and oven toaster.

These are stu I put for kids, and the food, everything [that] belongs to kids, I put it downstairs. I don't need to come

upstairs. It is near - I can watch the kids.”

Seven of the 12 educators reported that they had their own backyard. Others used local playgrounds.

CHARACTERISTICS OF FAMILIES SERVED BY THE NETWORK

The majority of families served by FCC educators at the network were working professionals who paid privately for child care. Our

focus group included four married, college-educated mothers, three of whom had master’s degrees. (See Appendix B, Table B.3.)

APPROACHES TO SERVICE DELIVERY

Approaches to service delivery consisted of both relational and logistical implementation supports. Relational aspects included devel-

oping supportive and professional partnerships between network sta and aliated educators. Logistical aspects of implementation

included dosage (frequency and intensity) and content of services.

RELATIONAL ASPECTS OF SERVICE DELIVERY

At Little People FCCN, sta-educator relationships were developed through visits to FCC homes where one-on-one interactions

shaped the quality of relationships. Based on educator and sta responses to similar survey questions, approximately equal propor-

tions of educators (30%) and sta specialists (40%) saw their relationships as supervisors. More educators, however, viewed their re-

lationships with sta as like a friend or family (43%) compared to sta who did not describe relationships in this way. Sta were more

likely to view their relationships with educators as a mentoring relationship (40%) or a consulting partnership (20%). (See Appendix

B, Table B.4.)

In their conceptual model of high-quality support in home-based child care, Bromer and Korfmacher (2017) posit that emotional con-

nections and collaboration around goal-setting may be crucial elements of partnerships between FCC educators and support sta.

More than 93% of the FCC educators at Little People FCCN who responded to our survey reported strong endorsement of statements

about their specialists oering emotional support, help with goal setting, useful and responsive information, and communication.

Smaller proportions of educators, however, indicated that they felt like equal partners with sta (86%) or that their specialist cared

about them even if they did things the specialist did not agree with (67%). An even smaller proportion (12%) reported that they did

not feel their voices were heard. (See Appendix B, Table B.5.)

Specialists also reported strong emotional connections with educators including appreciation and respect. Survey responses indicat-

ed that they set goals with educators, took educators’ perspectives when interacting with them and oering support, and accepted

educators’ views even when they diered from their own.

Cultural responsiveness. Research suggests that cultural sensitivity and responsiveness are important aspects of relationships

between sta and educators, especially in terms of engaging educators in services (Blasberg et al., 2019; Bromer & Korfmacher, 2017;

Porter et al., 2010). Interviews and surveys with sta specialists and educators at Little People FCCN confirmed that language and

cultural barriers may have shaped the interactions that occurred at the network between specialists and educators. Sta at Little

People FCCN were primarily white and educators were primarily immigrant women from South Asia and the Middle East. None of

the specialists interviewed reported that they had any training in cultural responsiveness or relationship-based practices with adult

17

INSIDE FAMILY CHILD CARE NETWORKS

CHAPTER II

learners. A supervisor for some of the specialists explained some of the challenges that specialists faced:

• “We have so many dierent cultures. … For our child care specialists, some of them didn’t have any experience really working

with dierent cultures in this way before they came into this position. I think some do better than others.”

Our survey data suggest that two of the five child care specialists found it challenging to work with educators who may have had

dierent beliefs or cultural values around childrearing. Specialists reported not knowing about the cultural values of educators in their

caseload. Interviews with specialists confirmed their challenges negotiating dierent languages and childrearing styles:

• “Making sure that they understand, that’s my biggest goal. That can be a challenge sometimes, especially if the language is a

big enough of an issue.”

• “I don’t think they do understand the language, we try-I’m very understanding, because English is not my first language

either, but I wish they would make more of an eort. If they’re working with American families, they need to speak English.

It’s like, you need to know who you’re talking to and everything like that.”

• “I think it's wonderful that they do have dierent ideas. They do things dierently. There are certain things though that

culturally sometimes are hard for me. Number one is they forever think that they need to feed these kids. Sometimes they

use the same spoon. That's a cultural thing. We tell them, ‘You can't do that. The child needs its own spoon. You can feed

them, but if you're doing it this way, you need three bowls. You need three spoons.’”

The mismatch in cultural background between specialists and educators may have been challenging for educators as well. Survey

responses indicated that 18% of FCC educators reported discomfort with sharing information about their faith or religious practices,

and 10% reported feeling uncomfortable sharing information about their culture and cultural values with their specialist (Appendix B,

Table B.6). Although these are relatively low percentages, they are notable given the positive reports of relationships in other survey

responses. The majority of educators at Little People FCCN who participated in our study self-identified as Asian or Pacific Islanders,

and English may have been their second language. A fifth of educators who responded to our survey reported they did not receive

help and support in their preferred language.

Personal support. Specialists at Little People FCCN recognized that FCC work could be isolating and took time during visits to listen

to educators’ personal situations. However, personal support was not a primary focus or purpose of visits. As one specialist noted:

• “Some providers think that’s helpful—that when I’m there, it’s like an adult to talk to, their concerns, or to just talk. They

spend the whole day with children. Some of them really like when I go… I think they enjoy the home visits, as a whole. They

do expect me to come, and they have things to share. They do enjoy the conversations we have. I had a provider that said,

‘Oh, it was nice when you come, because we can talk,’ because we talk about various things. I think they enjoy that, the

company.”

Another specialist echoed this observation that educators often just needed to share with another adult the things happening in their

lives:

• “Sometimes there’s a variety of things with their own kids. I had a provider who had a child being bullied in school.

Sometimes they don’t just talk about daycare. They do have their own lives. Wow, there’s someone to talk to.”

Specialists at Little People FCCN reported challenges around setting boundaries with educators between professional and personal

relationships. As reported earlier, educators at Little People FCCN viewed their relationships with sta like family or friends. Sta

viewed the relationships as more professional, although three out of five specialists reported that they gave out their personal con-

tact information to educators in their caseloads. One specialist reported that she set limits on when educators could reach and call

her. Another specialist explained that she aimed to “keep things professional” by not responding to friend requests from educators on

Facebook:

• “I’m not your friend. I do enjoy the time we spend together. [Laughter] I’m happy to listen with you. I like to watch your

children grow up, but there’s limits to that.”

18

INSIDE FAMILY CHILD CARE NETWORKS

CHAPTER II

LOGISTICAL ASPECTS OF SERVICE DELIVERY

Research suggests that the frequency and intensity of services may influence quality as well as provider, child, and family outcomes

(Bromer & Korfmacher, 2017; Fixsen et al., 2005; Halle et al., 2013; Paulsell et al., 2010). Little People FCCN oered services including

visits to FCC homes, training, and peer supports. The network did not have separate services or supports for parents and families

beyond administration of parent fees and negotiating of educator-family relationships which are discussed in later sections.

Visits to FCC homes. The four child care specialists conducted monthly unannounced visits as well as an annual licensing visit and

three annual food program visits. Although licensing and food program visits were based on monitoring protocols, monthly visits

could be more flexible. One specialist noted this when she said, “What you do depends on what you walk into.” Sometimes she need-

ed to help with care of children depending on what was happening in the moment she arrived at the home:

• “You may walk in, the parent could still be there dropping their child o, maybe they've been to a doctor's appointment and

they've come back. Maybe the infant or child's just gotten shots. They could be fussy. You might want to help by holding the

baby. If there's anything I can do to help the provider with the kids, and if the kids are willing to come to me, I'm more than

willing to do that to assist.”

According to survey responses, a majority of educators did not find visits to be disruptive. All four child care specialists reported

that educators were engaged in visits and sometimes took initiative in bringing up topics for discussion. However, the unannounced

nature of visits may have accounted for a small percentage of educators feeling that visits were stressful, took time away from their

care of children, or made children feel uncomfortable. (See Appendix B, Tables B.7-B.8.) Four educators in our interviews described

visits as stressful and emphasized the “surprise” nature of unannounced visits. One reported, “I can’t handle it. My mind is on the

kids.” Another educator reported that she felt unfairly evaluated by her specialist for not focusing on children during an unannounced

visit where she had to ask her husband to watch the children. She described how her specialist wrote up a report about how she did

not “play with the kids” during the visit.

Training. Training workshops oered at Little People FCCN were taught by sta members and outside trainers. Both online and

in-person trainings were oered during times that were convenient for educators including evenings and weekends. Educators also

acquired training hours through one-on-one specialist visits.

The network oered a variety of training topics that included health and safety, quality caregiving, business management, working

with families, and self-care. Training topics were based on educator input and sta reports of needs based on visits to FCC homes.

For example, one sta specialist explained, “If we know that a provider is a struggling with doing art with infants and toddlers, we’re

going to plan a training on that.”

Once licensed, FCC educators were required by the state to complete 16 hours of continuing education annually. These trainings

were free of charge and oered at the network’s oce. In addition, specialists played a role in helping educators keep track of these

required training hours, notifying them about upcoming training opportunities, and recommending certain training topics.

Peer supports. Three primary peer support strategies to foster connections among educators at Little People FCCN emerged from

director and sta interviews: 1) an annual educator appreciation luncheon; 2) an international dinner for educators; and 3) opportuni-

ties to network with other educators at training workshops. In addition, the network distributed a directory with educator names and

contact information, which served as a vehicle for communication across the network. Little People FCCN did not provide any other

formal peer support services such as support groups, learning communities or cohorts nor did the child care specialists see their role

as promoting connections among educators.

In the survey, we asked broadly about peer supports. Approximately a third (35%) of educators who responded to the survey indi-

cated wanting to meet other educators as a reason for joining the network. Slightly more than four in ten (44%) reported that they

participated in social activities or an educator recognition event. A third (34%) reported that they participated in a peer networking

opportunity which was most likely during training, according to our interviews with the director and sta. Nearly a quarter of educa-

tors indicated that they did not participate in any peer support activities. See Table B.9.

Ten of the twelve educators who participated in interviews reported that they attended the appreciation luncheon, the international

dinner and/or networking at training. The Provider Appreciation Luncheon was an annual event intended to “honor” the educators in

the network, “kind of like Teacher Appreciation Week.” Educators cited the event as an opportunity to get together with other FCC

educators: “That day you have new faces, so you introduce yourself… and so many things happen.” The International Potluck dinner

19

INSIDE FAMILY CHILD CARE NETWORKS

CHAPTER II

for educators, parents, and children was a long-standing annual event and was an opportunity for everyone in the network to get

together. The potluck dinner facilitated cross-cultural sharing; the most recent dinner included play workshops where FCC educators

set up dierent activity stations for parents and children.

Besides these two social events, interviews with educators and sta indicated that networking at training workshops was the most

common way that educators connected with each other. One educator explained: “Because of the training… we are together, not only

the ones in my area, even the other ones. We have a great relationship because of [Little People FCCN].”

SUMMARY: APPROACHES TO SERVICE DELIVERY AT LITTLE PEOPLE FCCN

Relational aspects of service delivery

• Sta specialists and FCC educators at Little People FCCN held contrasting views of their relationships with

each other. Educators were more likely to view the relationships as a friend or family compared to sta who

were more likely to see the relationship as a mentoring one.

• Specialists reported that they discussed personal issues with educators, but it was not a focus of their work.

They tried to set boundaries between personal and professional relationships with educators.

• The majority of educators reported strong endorsement of statements about their specialists oering

emotional support, help with goal setting, useful and responsive information, and communication.

• As many as a fifth of educators reported negative aspects of their relationships with specialists including not

feeling treated as equal partners and feeling that sta did not care about or were not familiar with their FCC

needs and circumstances.

• The mismatch between educator and sta cultural and linguistic backgrounds created challenges in these

relationships, especially during network specialist visits to FCC homes.

Logistical aspects of service delivery

• Monthly network visits to FCC homes were perceived as positive experiences by most educators who

responded to the survey. However, interviews with educators suggested that some found the surprise nature

of unannounced visits to be stressful and felt misunderstood by their specialists during visits which may have

been related to the cultural and linguistic mismatch between sta and educators.

• Network training included a variety of topics based on educator input as well as sta reports on educators’

needs. Training was oered in educator homes, at the network oce, or online and could be applied to the

state’s required training hours.

• Few formal opportunities for peer support, outside of two annual events and informal networking at training

workshops, were oered by the network.

20

INSIDE FAMILY CHILD CARE NETWORKS

CHAPTER II

SUPPORTING QUALITY

This section describes the relationship between observed caregiving quality among educators at Little People FCCN and the supports

the network oered on improving quality. First we report on findings from observations of educator-child interactions and the

learning environment in FCC homes and how the network supports these areas of quality. Second, we report on how the network

supported educators around working with families. Third, we report on findings from observations of health and safety practices and

how the network enforces compliance to health and safety licensing regulations. Throughout these sections, we describe the tensions

between supporting quality caregiving practices and enforcing licensing regulations because Little People FCCN was both a network