Working PaPer SerieS

no 1565 / july 2013

riSk, uncertainty

and Monetary Policy

Geert Bekaert, Marie Hoerova

and Marco Lo Duca

In 2013 all ECB

publications

feature a motif

taken from

the €5 banknote.

note: This Working Paper should not be reported as representing

the views of the European Central Bank (ECB). The views expressed are

those of the authors and do not necessarily reect those of the ECB.

© European Central Bank, 2013

Address Kaiserstrasse 29, 60311 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Postal address Postfach 16 03 19, 60066 Frankfurt am Main, Germany

Telephone +49 69 1344 0

Internet http://www.ecb.europa.eu

Fax +49 69 1344 6000

All rights reserved.

ISSN 1725-2806 (online)

EU Catalogue No QB-AR-13-062-EN-N (online)

Any reproduction, publication and reprint in the form of a different publication, whether printed or produced electronically, in whole

or in part, is permitted only with the explicit written authorisation of the ECB or the authors.

This paper can be downloaded without charge from http://www.ecb.europa.eu or from the Social Science Research Network electronic

library at http://ssrn.com/abstract_id=1561171.

Information on all of the papers published in the ECB Working Paper Series can be found on the ECB’s website, http://www.ecb.

europa.eu/pub/scientic/wps/date/html/index.en.html

Acknowledgements

We thank the Associate Editor, Refet Gürkaynak, and an anonymous referee for suggestions that signicantly improved the paper. We

are also grateful to Tobias Adrian, Gianni Amisano, David DeJong, Bartosz Mackowiak, Frank Smets, José Valentim and Jonathan

Wright for their very helpful comments on earlier drafts. Falk Bräuning and Carlos Garcia provided excellent research assistance. The

views expressed do not necessarily reect those of the European Central Bank or the Eurosystem. Bekaert gratefully acknowledges

nancial support from Netspar.

Geert Bekaert

Columbia University

Marie Hoerova

European Central Bank; e-mail: [email protected]

Marco Lo Duca

European Central Bank; e-mail: [email protected]

1

ABSTRACT

The VIX, the stock market option-based implied volatility, strongly co-moves with measures of

the monetary policy stance. When decomposing the VIX into two components, a proxy for risk

aversion and expected stock market volatility (“uncertainty”), we find that a lax monetary policy

decreases both risk aversion and uncertainty, with the former effect being stronger. The result

holds in a structural vector autoregressive framework, controlling for business cycle movements

and using a variety of identification schemes for the vector autoregression in general and

monetary policy shocks in particular. The effect of monetary policy on risk aversion is also

apparent in regressions using high frequency data.

JEL Codes: E44, E52, G12, G20, E32

Keywords: Monetary policy, option implied volatility, risk aversion, uncertainty, business

cycle

2

NON-TECHNICAL SUMMARY

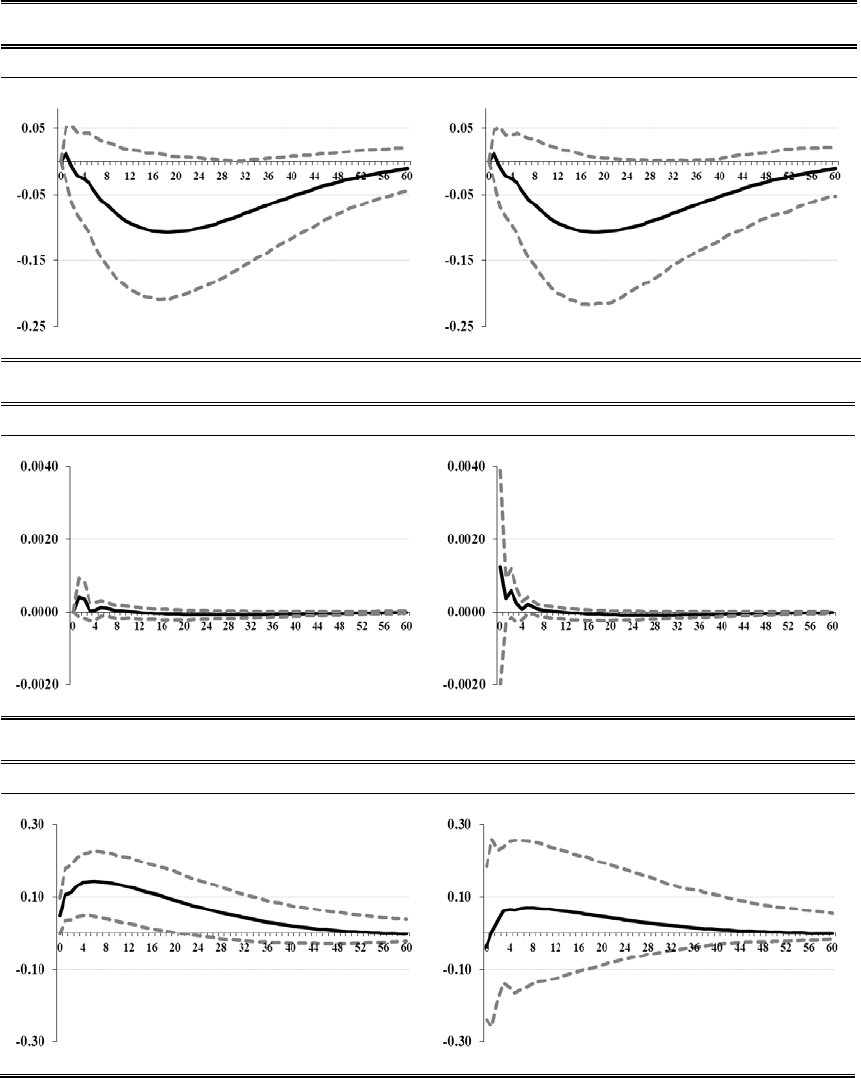

A popular indicator of risk aversion in financial markets, the VIX index, strongly co-moves with

measures of the monetary policy stance in the United States. While the current VIX is positively

associated with future (real) Fed funds rates, the relationship turns negative and significant after

13 months: high VIX readings are correlated with expansionary monetary policy in the medium-

run future (see Figure 1).

The strong interaction between the VIX index, known as a “fear index” (Whaley (2000)), and

monetary policy indicators may have important implications for a number of literatures. First,

the recent crisis has rekindled the idea that loose monetary policy may lead to excessive risk-

taking in financial markets. The Federal Reserve’s pattern of providing liquidity to financial

markets following market tensions, which became known as the “Greenspan put,” has been

cited as one of the contributing factors to the build-up of a speculative bubble prior to the 2007-

09 financial crisis.

Second, Bloom (2009) and Bloom, Floetotto and Jaimovich (2009) show that heightened

“economic uncertainty” decreases employment and output. It is therefore conceivable that the

monetary authority responds to uncertainty shocks, in order to affect economic outcomes.

However, the VIX index, used by Bloom (2009) to measure uncertainty, can be decomposed

into a component that reflects actual expected stock market volatility (uncertainty) and a

residual, the so-called variance premium, that reflects risk aversion and other non-linear pricing

effects, perhaps even Knightian uncertainty. Establishing which component drives the strong

co-movements between the monetary policy stance and the VIX is therefore particularly

important.

Third, analyzing the relationship between monetary policy and the VIX and its components may

help clarify the relationship between monetary policy and the stock market, explored in a large

number of empirical papers (Thorbecke (1997), Rigobon and Sack (2004), Bernanke and

Kuttner (2005)). The extant studies all find that expansionary (contractionary) monetary policy

affects the stock market positively (negatively). Interestingly, Bernanke and Kuttner (2005)

ascribe the bulk of the effect to easier monetary policy lowering risk premiums, reflecting both a

reduction in economic and financial volatility and an increase in the capacity of financial

investors to bear risk. By using the VIX and its two components, we test the effect of monetary

policy on stock market risk, but also provide more precise information on the exact channel.

This article characterizes the dynamic links between risk aversion, uncertainty and monetary

policy in a structural vector autoregressive (VAR) framework. Our VARs always include a

business cycle indicator to control for business cycle movements. The main findings are as

3

follows. A lax monetary policy decreases risk aversion in the stock market after about nine

months. This effect is persistent, lasting for more than two years. Moreover, monetary policy

shocks account for a significant proportion of the variance of the risk aversion proxy. Monetary

policy shocks have a significant impact on risk aversion also in regressions using high

frequency data. The effects of monetary policy on uncertainty are similar but somewhat weaker.

On the other hand, periods of both high uncertainty and high risk aversion are followed by a

looser monetary policy stance but these results are less robust and weaker statistically. Finally, it

is the uncertainty component of the VIX that has the statistically stronger effect on the business

cycle, not the risk aversion component.

4

1 INTRODUCTION

A popular indicator of risk aversion in financial markets, the VIX index, shows strong co-

movements with measures of the monetary policy stance. Figure 1 considers the cross-

correlogram between the real interest rate (the Fed funds rate minus inflation), a measure of the

monetary policy stance, and the logarithm of end-of-month readings of the VIX index. The VIX

index essentially measures the “risk-neutral” expected stock market variance for the US

S&P500 index. The correlogram reveals a very strong positive correlation between real interest

rates and future VIX levels. While the current VIX is positively associated with future real rates,

the relationship turns negative and significant after 13 months: high VIX readings are correlated

with expansionary monetary policy in the medium-run future.

- Figure 1 -

The strong interaction between a “fear index” (Whaley (2000)) in the asset markets and

monetary policy indicators may have important implications for a number of literatures. First,

the recent crisis has rekindled the idea that lax monetary policy can be conducive to financial

instability. The Federal Reserve’s pattern of providing liquidity to financial markets following

market tensions, which became known as the “Greenspan put,” has been cited as one of the

contributing factors to the build-up of a speculative bubble prior to the 2007-09 financial crisis.

1

Whereas some rather informal stories have linked monetary policy to risk-taking in financial

markets (Rajan (2006), Adrian and Shin (2008), Borio and Zhu (2008)), it is fair to say that no

extant research establishes a firm empirical link between monetary policy and risk aversion in

asset markets.

2

Second, Bloom (2009) and Bloom, Floetotto and Jaimovich (2009) show that heightened

“economic uncertainty” decreases employment and output. It is therefore conceivable that the

monetary authority responds to uncertainty shocks, in order to affect economic outcomes.

However, the VIX index, used by Bloom (2009) to measure uncertainty, can be decomposed

into a component that reflects actual expected stock market volatility (uncertainty) and a

residual, the so-called variance premium (see, for example, Carr and Wu (2009)), that reflects

risk aversion and other non-linear pricing effects, perhaps even Knightian uncertainty.

Establishing which component drives the strong co-movements between the monetary policy

stance and the VIX is therefore particularly important.

1

Investors increasingly believed that when market conditions were to deteriorate, the Fed would step in and inject liquidity until

the outlook improved. See, for example, “Greenspan Put May be Encouraging Complacency,” Financial Times, December 8,

2000.

2

For recent empirical evidence that monetary policy affects the riskiness of loans granted by banks see, for example, Altunbas,

Gambacorta and Marquéz-Ibañez (2010), Ioannidou, Ongena and Peydró (2009), Jiménez, Ongena, Peydró and Saurina (2009),

and Maddaloni and Peydró (2011).

5

Third, analyzing the relationship between monetary policy and the VIX and its components may

help clarify the relationship between monetary policy and the stock market, explored in a large

number of empirical papers (Thorbecke (1997), Rigobon and Sack (2004), Bernanke and

Kuttner (2005)). The extant studies all find that expansionary (contractionary) monetary policy

affects the stock market positively (negatively). Interestingly, Bernanke and Kuttner (2005)

ascribe the bulk of the effect to easier monetary policy lowering risk premiums, reflecting both a

reduction in economic and financial volatility and an increase in the capacity of financial

investors to bear risk. By using the VIX and its two components, we test the effect of monetary

policy on stock market risk, but also provide more precise information on the exact channel.

This article characterizes the dynamic links between risk aversion, economic uncertainty and

monetary policy in a simple vector-autoregressive (VAR) system. Such analysis faces a number

of difficulties. First, because risk aversion and the stance of monetary policy are jointly

endogenous variables and display strong contemporaneous correlation (see Figure 1), a

structural interpretation of the dynamic effects requires identifying restrictions. Monetary policy

may indeed affect asset prices through its effect on risk aversion, as suggested by the literature

on monetary policy news and the stock market, but monetary policy makers may also react to a

nervous and uncertain market place by loosening monetary policy. In fact, Rigobon and Sack

(2003) find that the Federal Reserve does systematically respond to stock prices.

3

Second, the relationship between risk aversion and monetary policy may also reflect the joint

response to an omitted variable, with business cycle variation being a prime candidate.

Recessions may be associated with high risk aversion (see Campbell and Cochrane (1999) for a

model generating counter-cyclical risk aversion) and at the same time lead to lax monetary

policy. Our VARs always include a business cycle indicator.

Third, measuring the monetary policy stance is the subject of a large literature (see, for example,

Bernanke and Mihov (1998a)); and measuring policy shocks correctly is difficult. Models

featuring time-varying risk aversion and/or uncertainty, such as Bekaert, Engstrom and Xing

(2009), imply an equilibrium contemporaneous link between interest rates and risk aversion and

uncertainty, through precautionary savings effects for example. Such relation should not be

associated with a policy shock. However, our results are robust to alternative measures of the

monetary policy stance and of monetary policy shocks. In particular, the results are robust to

identifying monetary policy shocks using a standard structural VAR, using high frequency Fed

funds futures changes following Gürkaynak, Sack and Swanson (2005), and using the approach

3

Rigobon and Sack (2003, 2004) use an identification scheme based on the heteroskedasticity of stock market returns. Given that

we view economic uncertainty as an important endogenous variable in its own right with links to the real economy and risk

premiums, we cannot use such an identification scheme.

6

in Bernanke and Kuttner (2005), based on the unexpected change in the Fed Funds rate on a

monthly basis.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 details the measurement of the

key variables in the VAR, including monetary policy indicators, monetary policy shocks and

business cycle indicators. First and foremost, we provide intuition on how the VIX is related to

the actual expected variance of stock returns and to risk preferences. While the literature has

proposed a number of risk appetite measures (see Baker and Wurgler (2007) and Coudert and

Gex (2008)), our measure is monotonically increasing in risk aversion in a variety of realistic

economic settings. This motivates our empirical strategy in which the VIX is split into a pure

volatility component (“uncertainty”) and a residual, which should be more closely associated

with risk aversion. Section 3 analyzes the dynamic relationship between monetary policy and

risk aversion and uncertainty in standard structural VARs. The results are remarkably robust to

a long list of robustness checks with respect to VAR specification, variable definitions and

alternative identification methods. Section 4 employs two alternative methods to identify

monetary policy shocks relying on Fed futures data.

4

Our main findings are as follows. A lax monetary policy decreases risk aversion in the stock

market after about nine months. This effect is persistent, lasting for more than two years.

Moreover, monetary policy shocks account for a significant proportion of the variance of the

risk aversion proxy. Monetary policy shocks have a significant impact on risk aversion also in

regressions using high frequency data. The effects of monetary policy on uncertainty are similar

but somewhat weaker. On the other hand, periods of both high uncertainty and high risk

aversion are followed by a looser monetary policy stance but these results are less robust and

weaker statistically. Finally, it is the uncertainty component of the VIX that has the statistically

stronger effect on the business cycle, not the risk aversion component.

4

The Online Appendix, available at www.mariehoerova.net, contains supplementary material referenced in the article.

7

2 MEASUREMENT

This section details the measurement of the key inputs to our analysis: risk aversion and

uncertainty; the monetary policy stance and monetary policy shocks; and finally, business cycle

variation. Our data start in January 1990 (the start of the model-free VIX series) but our analysis

is performed using two different end-points for the sample: July 2007, yielding a sample that

excludes recent data on the crisis; and August 2010. The crisis period presents special

challenges as stock market volatilities peaked at unprecedented levels and the Fed funds target

rate reached the zero lower bound. Table 1 describes the basic variables used and assigns them a

short-hand label.

- Table 1 –

2.1 MEASURING RISK AVERSION AND UNCERTAINTY

To measure risk aversion and uncertainty, we use a decomposition of the VIX index. The VIX

represents the option-implied expected volatility on the S&P500 index with a horizon of 30

calendar days (22 trading days). This volatility concept is often referred to as “implied

volatility” or “risk-neutral volatility,” as opposed to the actual (or “physical”) expected

volatility. Intuitively, in a discrete state economy, the physical volatility would use the actual

state probabilities to arrive at the physical expected volatility, whereas the risk-neutral volatility

would make use of probabilities that are adjusted for the pricing of risk.

The computation of the actual VIX index relies on theoretical results showing that option prices

can be used to replicate any bounded payoff pattern; in fact, they can be used to replicate

Arrow-Debreu securities (Breeden and Litzenberger (1978), Bakshi and Madan (2000)). Britten-

Jones and Neuberger (2000) and Bakshi, Kapadia and Madan (2003) show how to infer “risk-

neutral” expected volatility for a stock index from option prices. The VIX index measures

implied volatility using a weighted average of European-style S&P500 call and put option

prices that straddle a 30-day maturity and cover a wide range of strikes (see CBOE (2004) for

more details). Importantly, this estimate is model-free and does not rely on an option pricing

model.

While the VIX obviously reflects stock market uncertainty, it conceptually must also harbor

information about risk and risk aversion. Indeed, financial markets often view the VIX as a

measure of risk aversion and fear in the market place. Because there are well-accepted

techniques to measure the physical expected variance, the VIX can be split into a measure of

stock market or economic uncertainty, and a residual that should be more closely associated

with risk aversion. The difference between the squared VIX and an estimate of the conditional

8

variance is typically called the variance premium (see, e.g., Carr and Wu (2009)).

5

The variance

premium is nearly always positive

and displays substantial time-variation. Recent finance

models attribute these facts either to non-Gaussian components in fundamentals and (stochastic)

risk aversion (see, for instance, Bekaert and Engstrom (2013), Bollerslev, Tauchen and Zhou

(2009), Drechsler and Yaron (2011)) or Knightian uncertainty (see Drechsler (2009)). Bekaert

and Hoerova (2013) use a one-period discrete economy with power utility to illustrate the

difference between “risk neutral” and “physical” expected variance and demonstrate that the

variance premium is indeed increasing in risk aversion in a number of realistic calibrated

example economies.

2.1.1 DECOMPOSING THE VIX INDEX

To decompose the VIX index into a risk aversion and an uncertainty component, an estimate of

the expected future realized variance is needed. This estimate is customarily obtained by

projecting future realized monthly variances (computed using squared 5-minute returns) onto a

set of current instruments. We follow this approach using daily data on monthly realized

variances (denoted by RVAR), the squared VIX, the dividend yield and the real three-month T-

bill rate. By using daily data, considerable statistical power is gained relative to the standard

methods employing end-of-month data. For example, forecasting models estimated from daily

data easily “beat” models using only end-of-month data, even for end-of-month samples.

To select a good forecasting model, a horserace is conducted between a total of eight volatility

forecasting models. The first five models use OLS regressions with different predictors: a one-

variable model with either the past realized variance or the squared VIX; a two-variable model

with both the squared VIX and the past realized variance; a three-variable model adding the past

dividend yield; and a four-variable model adding the past real three-month T-bill rate. Three

models that do not require estimation are also considered: half-half weights on the past squared

VIX and past realized variance; the past realized variance; the past squared VIX. Our model

selection criteria are out-of-sample root mean squared error and mean absolute errors, and, for

the estimated models, stability (especially through the crisis period).

This procedure leads us to select a two-variable model where the squared VIX and the past

realized variance are used as predictors. The performance of the three- and four-variable models

is very comparable to this model, but the univariate estimated models and the non-estimated

models perform consistently and significantly worse. Moreover, the selected model is the most

stable of the well-performing forecasting models we considered, with the coefficients

5

In the technical finance literature, the variance premium is actually the negative of the variable that we use. By switching the

sign, our indicator tends to increase with risk aversion, whereas the variance premium becomes more negative with risk aversion.

9

economically and statistically unaltered during the crisis period. The Online Appendix provides

a detailed account of the forecasting horserace. The resulting coefficients from the two-variable

projection are as follows:

6

RVAR

t

=-0.00002 + 0.299 VIX

2

t-22

+ 0.442 RVAR

t-22

+e

t

(1)

(0.00012) (0.067) (0.130)

The standard errors reported in parentheses are corrected for serial correlation using 30 Newey-

West (1987) lags.

The fitted value from the two-variable projection is the estimated conditional variance and our

measure of “uncertainty.” The difference between the squared VIX and the conditional variance

is our measure of “risk aversion.”

2.1.2 RISK AVERSION AND UNCERTAINTY ESTIMATES

Figure 2 plots the risk aversion and uncertainty estimates, along with 90% confidence intervals.

7

To construct the confidence bounds, the coefficients from the forecasting projection together

with their asymptotic covariance matrix are retained. Then, 100 alternative parameter

coefficients from the distribution of these estimates are drawn, which generates alternative risk

aversion and uncertainty estimates. In Section 3.3.4, these bootstrapped series are used to

account for the sampling error in the risk aversion and uncertainty estimates in our VARs.

Throughout our analysis, the logarithms of the risk aversion and uncertainty estimates are used.

They are labeled RA and UC, respectively.

- Figure 2–

2.2 MEASURING MONETARY POLICY

To measure the monetary policy stance, we use the real interest rate (RERA), i.e., the Fed funds

end-of-the-month target rate minus the CPI annual inflation rate. In Section 3.3.1, alternative

measures of the monetary policy stance are considered for robustness. Our first such measure is

the Taylor rule residual, the difference between the nominal Fed funds rate and the Taylor rule

rate (TR rate). The TR rate is estimated as in Taylor (1993):

TR

t

= Inf

t

+ NatRate

t

+ 0.5 (Inf

t

- TargInf) + 0.5 OG

t

(2)

6

This estimation was conducted using a winsorized sample but the estimation results for the non-winsorized sample are in fact very

similar.

7

The estimated uncertainty series is less “jaggedy” than it would be if only the past realized variance would be used to compute it

(as in Bollerslev, Tauchen and Zhou, 2009), which in turn helps smooth the risk aversion process.

10

where Inf is the annual inflation rate, NatRate is the “natural” real Fed funds rate (consistent

with full employment), which Taylor assumed to be 2%, TargInf is a target inflation rate, also

assumed to be 2%, and OG (output gap) is the percentage deviation of real GDP from potential

GDP; with the latter obtained from the Congressional Budget Office. Our other alternative

measures of the monetary policy stance are the nominal Fed funds rate instead of the real rate,

and (the growth rate of) the monetary aggregate M1, which is commonly assumed to be under

tight control of the central bank. M1 (growth) is multiplied by minus one so that a positive

shock to this variable corresponds to monetary policy tightening, in line with all of our other

measures of monetary policy.

Measuring the monetary policy stance is challenging since late 2008, as the Fed funds rate

reached the zero lower bound (the Fed funds target was set in the range 0-0.25% as of

December 2008) and the Federal Reserve turned to unconventional monetary policies, such as

large-scale asset purchases. In the period December 2008 - August 2010, the “true” nominal Fed

funds rate is approximated by taking it to be the minimum between 0.125% (i.e., the mid-point

of the 0-0.25% range) and the TR rate, estimated using equation (2) above. Rudebusch (2009)

has also advocated using the TR rate estimate as a proxy for the “true” Fed funds rate post-2008.

Our analysis in Sections 4.1 and 4.2 uses monetary policy surprises derived from Fed funds

futures data. Section 4.1 relies on monetary policy surprises proposed by Gürkaynak, Sack and

Swanson (2005), henceforth GSS.

8

GSS compute the monetary policy surprises as high-

frequency changes in the futures rate around the FOMC announcements. Their “tight” (“wide”)

window estimates begin ten (fifteen) minutes prior to the monetary policy announcement and

end twenty (forty-five) minutes after the policy announcement, respectively. The data span the

period from January 1990 through June 2008. Section 4.2 uses the unexpected change in the Fed

funds rate on a monthly basis, defined as the average Fed funds target rate in month t minus the

one-month futures rate on the last day of the month t-1. This approach follows Kuttner (2001)

and Bernanke and Kuttner (2005) (henceforth BK), see their equation (5). As pointed out by

BK, rate changes that were unanticipated as of the end of the prior month may well include a

systematic response to economic news, such as employment, output and inflation occurring

during the month. To overcome this problem, “cleansed” monetary surprises that are orthogonal

to a set of economic data releases are used. They are calculated as residuals in a regression of

the “simple” monetary policy surprise, onto the unexpected component of the industrial

production index, the Institute of Supply Management Purchasing Managers Index (the ISM

index), the payroll survey, and unemployment (see Section 2.3 below for a description). Finally,

8

We are very grateful to R. Gürkaynak for sharing the data with us.

11

this regression allows for heterogeneous coefficients before and after 1994, to take into account

a change in the reaction of the Fed to economic data releases, as documented in BK.

To extend the sample of monetary policy surprises until August 2010, we proceed in two steps.

First, data on monetary policy surprises at the zero lower bound are collected from Wright

(2012, Table 5, p. F463). They represent the first principle component of intraday changes in

yields on Treasury futures contracts, taken on days of important policy announcements. The

shocks are positive (negative) when monetary policy is unexpectedly accommodative

(restrictive), and normalized to have a unit standard deviation. For comparability with the GSS

data, Wright’s shocks are rescaled by multiplying them by minus the standard deviation of the

GSS’s shocks, before appending them to the time series of GSS shocks. Second, the gap

between the data from GSS (June 2008) and Wright (November 2008) is filled by calculating

monetary policy surprises using monthly Federal funds futures, following BK.

2.3 MEASURING BUSINESS CYCLE VARIATION

Industrial production is used as our benchmark indicator of business cycle variation at the

monthly frequency. In a robustness exercise in Section 3.3.2, non-farm employment and the

ISM index are considered as alternative business cycle indicators.

Sections 4.1 and 4.2 use data on economic news surprises following the methodology in

Ehrmann and Fratzscher (2004).

9

Our analysis relies on unexpected components of news about

the industrial production index, the ISM index, the payroll survey, and unemployment. The

unexpected component of each news release is calculated as the difference between the released

data and the median expectation according to surveys. The Money Market Survey (MMS) is

used for the period 1990-2001 and Bloomberg for the period 2002-2010. The shocks are

standardized over the sample period.

9

We are very grateful to M. Ehrmann and M. Fratzscher for sharing their dataset with us.

12

3 STRUCTURAL MONETARY VARS

This section follows the identified monetary VAR literature and interprets the shock in the

monetary policy equation as the monetary policy shock. Our benchmark VAR, analyzed in

Section 3.1, consists of four variables: our risk aversion and uncertainty proxies (RA

t

and UC

t

),

the real interest rate as a measure of monetary policy stance (MP

t

), and the log-difference of

industrial production as a business cycle indicator (BC

t

). Alternative VARs are considered as

part of an extensive series of robustness checks discussed in Section 3.3. The business cycle is

the most important control variable as it is conceivable that, for example, news indicating

weaker than expected growth in the economy may simultaneously make a cut in the Fed funds

target rate more likely and cause people to be effectively more risk averse, because their

consumption moves closer to their “habit stock,” or because they fear a more uncertain future.

3.1 STRUCTURAL FOUR-VARIABLE VAR: SET-UP

The four variables of our benchmark VAR are collected in the vector Z

t

= [BC

t

, MP

t

, RA

t

UC

t

]'.

Without loss of generality, constants are ignored. Consider the following structural VAR:

A Z

t

= Φ Z

t-1

+ ε

t

(3)

where A is a 4x4 full-rank matrix and E[ε

t

ε

t

'] = I. Of main interest are the dynamic responses to

the structural shocks ε

t

. Of course, the reduced-form VAR is estimated first:

Z

t

= B Z

t-1

+ C ε

t

(4)

where B denotes A

-1

Φ and C denotes A

-1

. Our estimated VARs include 3 lags, as chosen by the

Akaike criterion.

Six restrictions on the VAR are needed to identify the system. Our first set of restrictions uses a

standard Cholesky decomposition of the estimate of the variance-covariance matrix. The

business cycle variable is ordered first, followed by the real interest rate, with risk aversion and

uncertainty ordered last. This captures the fact that risk aversion and uncertainty, stock market

based variables, respond instantly to monetary policy shocks, while the business cycle variable

is relatively more slow-moving. Effectively, this imposes six exclusion restrictions on the

contemporaneous matrix A, making it lower-triangular.

Our second set of restrictions combines five contemporaneous restrictions (also imposed under

the Cholesky decomposition above) with the assumption that monetary policy has no long-run

effect on the level of industrial production. This long-run restriction is inspired by the literature

13

on long-run money neutrality: money should not have a long run effect on real variables.

10

Following Blanchard and Quah (1989), the model with a long-run restriction (LR) involves a

long-run response matrix, denoted by D:

D ≡ (I - B)

-1

C. (5)

The system with five contemporaneous restrictions and one long-run exclusion restriction

corresponds to setting the [1,2] element in D equal to zero while freeing up the corresponding

element in A.

11

We couch our main results in the form of impulse-response functions (IRFs henceforth),

estimated in the usual way, and focus our discussion on significant responses. Bootstrapped

90% confidence intervals are based on 1000 replications. Our focus is on the pre-crisis sample

because the addition of the crisis period leads to an unstable VAR. The Online Appendix (Table

OA2) provides evidence on the stability of the VAR using a variety of tests. When a standard

Wald test for parameter stability after July 2007 is used, the null hypothesis of stability is

rejected at the 1% significance level for industrial production, the real interest rate and risk

aversion and at the 5% level for uncertainty. When the sup-Wald test of Andrews (1993) is

performed, the procedure finds significant break dates between June 2007 and October 2008,

except for the risk aversion variable where overall stability is rejected at the 10% level but no

significant break date is detected. Finally, the Andrews (2003) test, formally designed for a

break that occurs towards the end of the sample, is also performed. Results are in line with the

other two tests: the null hypothesis of no breakpoint in August 2007 is rejected at the 1%

significance level for all variables with the exception of risk aversion.

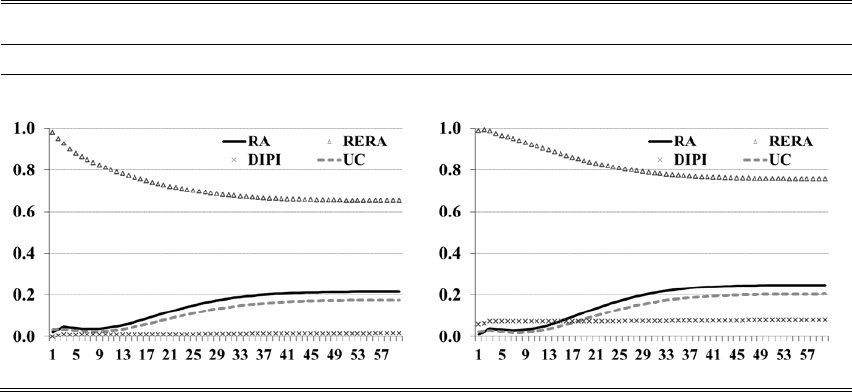

3.2 STRUCTURAL FOUR-VARIABLE VAR: RESULTS

Figure 3 graphs the complete results for the pre-crisis sample.

- Figure 3 -

Panels A and B show the interactions between the real rate (RERA) and log risk aversion (RA).

A one standard deviation negative shock to the real rate represents a 34 basis points decrease

under both identification schemes. Laxer monetary policy lowers risk aversion by about 0.032

in both models after 9 months. The impact reaches a maximum of 0.056 after 20 months and

remains significant up and till lag 40. A one standard deviation positive shock to risk aversion,

10

Bernanke and Mihov (1998b) and King and Watson (1992) marshal empirical evidence in favor of money neutrality using data

on money growth and output growth.

11

Both identification schemes satisfy necessary and sufficient conditions for global identification of structural vector

autoregressive systems (see Rubio-Ramírez, Waggoner and Zha (2010)).

14

which is equivalent to 0.347, has a mostly negative impact on the real rate but it is statistically

insignificant in both models.

As Panel C shows, a positive shock to the real rate has an immediate negative impact on

uncertainty. The impact is short-lived and only statistically significant in the model with

contemporaneous restrictions. In the medium run, tighter monetary policy increases uncertainty

in both models (between lags 11 and about 40). The maximum positive impact is about 0.060 at

lag 21 in both models. In the other direction, reported in Panel D, the real rate decreases in the

short-run following a positive one standard deviation shock to uncertainty, which is equivalent

to 0.244. In both models, the impact is (borderline) statistically insignificant.

As for interactions with the business cycle variable (Panels E through J), a contractionary

monetary policy shock leads to a decline in industrial production growth (DIPI) in the medium-

run, but the impact is statistically insignificant in both specifications. In the other direction,

monetary policy reacts as expected to business cycle fluctuations: a one standard deviation

positive shock to industrial production growth, equivalent to 0.005, leads to a higher real rate.

Specifically, in the model with contemporaneous restrictions, the real rate increases by a

maximum of 14 basis points after 6 months, with the impact being significant between lags 1

and 20. The impact is also positive in the model with contemporaneous/long-run restrictions but

it is not statistically significant. Interactions between risk aversion and industrial production

growth are mostly statistically insignificant. Positive uncertainty shocks lower industrial

production growth between lags 6-15, while the impact in the opposite direction is statistically

insignificant. This is consistent with the analysis in Bloom (2009), who found that uncertainty

shocks generate significant business cycle effects, using the VIX as a measure of uncertainty.

12

Finally, increases in risk aversion predict future increases in uncertainty under both

identification schemes (Panel L). Uncertainty has a positive, albeit short-lived effect on risk

aversion (Panel K).

Our main result for the pre-crisis sample is that monetary policy has a medium-run statistically

significant effect on risk aversion. This effect is also economically significant. Figure 4 shows

what fraction of the forecast error variance of the four variables in the VAR is due to monetary

policy shocks at horizons between 1 and 60 months. Monetary policy shocks account for over

20% of the variance of risk aversion at horizons longer than 37 and 29 months in the models

with contemporaneous and contemporaneous/long-run restrictions, respectively. They also

increase uncertainty and Figure 4 shows that they are only marginally less important drivers of

12

Popescu and Smets (2009) analyze the business cycle behavior of measures of perceived uncertainty and financial risk premia in

Germany. They find that financial risk aversion shocks are more important in driving business cycles than uncertainty shocks.

Gilchrist and Zakrajšek (2012) document that innovations to the excess corporate bond premium, a proxy for the time-varying

price of default risk, cause large and persistent contractions in economic activity.

15

the uncertainty variance than they are of the risk aversion variance. Finally, while monetary

policy appears to loosen in response to both risk aversion and uncertainty shocks, these effects

are statistically weaker.

- Figure 4 –

3.3 ROBUSTNESS

In this subsection, six types of robustness checks are considered: 1) measurement of the

monetary policy stance; 2) measurement of the business cycle variable; 3) alternative orderings

of variables; 4) accounting for the sampling error in RA and UC estimates; 5) conducting the

analysis using a six variable monetary VAR with the Fed funds rate and price level measures

CPI and PPI entering as separate variables; and 6) conducting the analysis over the full sample

till August 2010.

13

3.3.1 ALTERNATIVE MONETARY POLICY MEASURES

Three alternative measures of the monetary policy stance are considered: Taylor rule deviations,

nominal Fed funds rate and the growth of the monetary aggregate M1. The results (reported in

the Online Appendix, Table OA3) confirm that a looser monetary policy stance lowers risk

aversion in the short to medium run. This effect is persistent, lasting for about two years. In

some cases, the immediate effect has the reverse sign, however. In the other direction, monetary

policy becomes laxer in response to positive risk aversion shocks but the effect is statistically

significant in less than half the cases. As for the effect of monetary policy on uncertainty,

monetary tightening increases uncertainty in the medium run but this effect is not significant

when using the Fed fund rate. In the other direction, higher uncertainty leads to laxer monetary

policy in all specifications but the effect is only significant when using the Fed fund rate under

contemporaneous identifying restrictions.

3.3.2 ALTERNATIVE BUSINESS CYCLE MEASURES

As alternative business cycle indicators, the log-difference of employment and the log of the

ISM index are considered. Unlike industrial production and employment, the ISM index is a

stationary variable, implying that VAR shocks do not have a long run effect on it. Our long-run

restriction on the effect of monetary policy is thus stronger when applied to the ISM: it restricts

13

Moreover, our results remain robust to the use of both shorter and longer VAR lag-lengths. A VAR with 1 lag, as selected by the

Schwarz criterion, as well as a VAR with 4 lags were estimated (we did not go beyond four lags as otherwise the saturation ratio,

the ratio of data points to parameters, drops below 10). Our results were unaltered.

16

the total effect of monetary policy on the ISM to be zero. Nevertheless, our main results from

Section 3.1 are confirmed for each specification with an alternative business cycle variable.

Figures OA1 and OA2 in the Online Appendix present a full set of IRFs (the equivalent of

Figure 3) for the VARs with the log-difference of employment and the log of the ISM index,

respectively.

3.3.3 ALTERNATIVE ORDERINGS OF VARIABLES

In one alternative ordering, the order of risk aversion and uncertainty in our benchmark VAR is

reversed. In another robustness check, the real interest rate is ordered last, thus allowing it to

respond instantaneously to RA and UC shocks. We consistently find that looser monetary policy

lowers risk aversion and uncertainty in a statistically significant fashion in the medium-run. In

the other direction, the effects are less robust. In the specification with RA and UC reversed,

monetary policy mostly responds to UC shocks, while the response to RA shocks is statistically

insignificant. In the specification with RERA ordered last, monetary policy responds to both

positive RA and UC shocks by loosening its stance, and the effect is statistically significantly

different from zero. Figures OA3 and OA4 in the Online Appendix present a full set of IRFs for

the reversed ordering of RA and UC and for the specification with RERA ordered last,

respectively.

3.3.4 SAMPLING ERROR IN RA AND UC

This subsection verifies that our VAR results are robust to accounting for the sampling error in

the RA and UC estimation. Hundred alternative RA and UC series are drawn from the

distribution of RA and UC estimates (as described in Section 2.1.2) and fed into our

bootstrapped VAR. Per set of alternative RA and UC series, 100 VAR replications are

estimated. Then, the usual 90% confidence bounds are constructed. The results are very similar

to those obtained without taking uncertainty surrounding RA and UC estimates into account,

and are presented in the Online Appendix (Figure OA5).

3.3.5 SIX-VARIABLE MONETARY VAR

We also estimate a six-variable monetary VAR following Christiano, Eichenbaum and Evans

(1999) and featuring the nominal Fed funds rate as the measure of monetary policy stance and

price level measures CPI and PPI as additional variables.

14

To identify monetary policy shocks,

14

The model is estimated with four lags, as suggested by the Akaike criterion. All variables are in logarithms except for the Fed

funds rate. Note that industrial production now enters the VAR in levels.

17

a Cholesky ordering is used with CPI and industrial production ordered first, followed by the

Fed funds rate and PPI, and risk aversion and uncertainty ordered last.

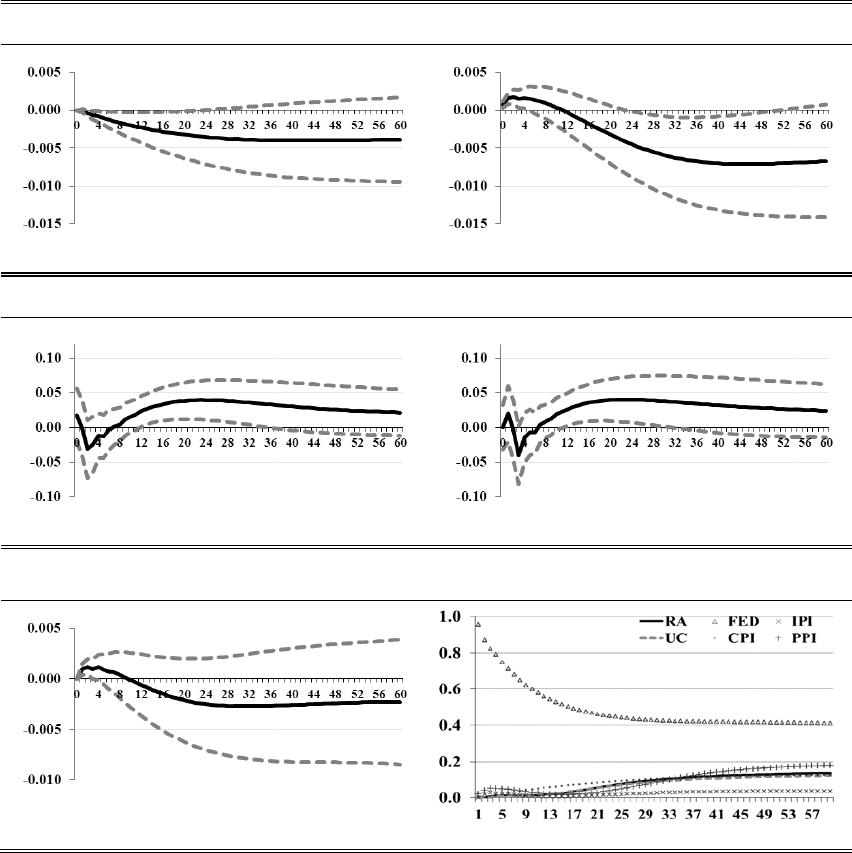

Figure 5 presents impulse-responses to monetary policy shocks. A positive monetary policy

shock corresponds to a 15 basis points increase in the Fed funds rate. A contractionary monetary

shock leads to a statistically significant decrease in the CPI between lags 3 and 23 and in the PPI

between lags 23 and 50. Furthermore, industrial production declines following a monetary

contraction after about 10 months, though the effect is not statistically significant. Importantly,

the reactions of both risk aversion and uncertainty are remarkably similar to those uncovered in

our benchmark four-variable VARs. Looser monetary policy decreases risk aversion by 0.024

after 12 months. The effect reaches a maximum of 0.040 at lag 23, and remains statistically

significant till lag 35. The effects remain economically important as monetary policy shocks

account for over 12% of the variance of risk aversion at horizons longer than 40 months (see

Panel F of Figure 5) but these percentages are nonetheless lower than in our four-variable VAR.

As for uncertainty, a higher Fed funds rate increases uncertainty between lags 12 and 31, with

the maximum impact of 0.040 at lag 23, which is also consistent with our previous findings. In

non-reported results, monetary policy responds to both positive RA and UC shocks by

loosening its stance. The effect is statistically significant between lags 2 and 7 for risk aversion

and between lags 5 and 26 for uncertainty.

- Figure 5–

3.3.6 FULL SAMPLE RESULTS

Despite the instability documented before, we nonetheless repeated our analysis for the full

sample including the crisis period. These results, mimicking Figure 3, can be found in the

Online Appendix (Figure OA6). The full sample results overall confirm our results for the pre-

crisis sample but are somewhat less statistically significant. The results regarding the key

interactions between monetary policy and risk aversion/uncertainty are as follows. The impact

of monetary policy in the full sample is quantitatively weaker, and is only statistically

significant at the 68% confidence level in both 4-variable VARs and the 6-variable VAR. Note

that such tighter confidence bounds are common in the VAR literature (see Christiano,

Eichenbaum, and Evans (1996), Sims and Zha (1999)). Monetary policy’s effect on uncertainty

is significant in the 6-variable VAR but borderline insignificant at the 68% level in the 4-

variable VARs. As to the reverse effect, monetary policy now reacts significantly to uncertainty

in some cases. Given the measurement problems mentioned before, and the rather extreme

volatility the VIX experienced, somewhat weaker statistical power for this sample is not entirely

surprising.

18

4 ALTERNATIVE IDENTIFICATION OF MONETARY

POLICY SHOCKS

In this Section, two alternative methodologies to identify monetary policy shocks are employed:

1) monetary surprises based on high-frequency Fed funds futures and 2) surprises based on the

unexpected change in the Fed Funds rate on a monthly basis. Focus is again on the pre-crisis

sample.

4.1 IDENTIFICATION USING HIGH-FREQUENCY FED FUNDS FUTURES

Our VAR set-up to identify monetary policy shocks and their structural relationship with risk

aversion and uncertainty follows the Sims (1980, 1998) identification tradition. With financial

market values changing continuously during the month, the use of monthly data for this purpose

certainly may cast some doubt on this identification scheme. An alternative identification

methodology that makes use of high frequency data is therefore employed to infer restrictions

on the monthly VAR.

4.1.1 IDENTIFICATION USING HIGH-FREQUENCY FED FUNDS FUTURES: SET-UP

Our approach, inspired by and building on the procedure described in D’Amico and Farka

(2011), consists of three steps. In the first step, the structural monetary policy and business cycle

shocks are measured directly. For monetary policy, we rely on a well-established literature that

uses high frequency changes in Fed funds futures rates to measure monetary policy shocks (see,

for example, Faust, Swanson and Wright, 2004). The measurement was detailed in Section 2.2.

Likewise, for business cycle shocks, news announcements are used. Under certain assumptions,

these shocks can be viewed as measuring the structural shocks ε

t

in the VAR. For monetary

policy shocks, this is plausible because usually only one shock occurs per month, and the use of

high frequency futures data helps ensure that the identified shock is plausibly orthogonal to

other shocks. As to the business cycle shocks, there are a number of potentially important

complicating issues, such as the correlation between the different news announcements and the

structural shock to the actual business cycle variable used in the VAR, and the scale of the

shocks when more than one occurs within a particular month. However, these issues become

moot when business cycle shocks do not generate significant contemporaneous effects on our

financial variables, which ends up being the case.

In the second step, the high frequency effects of monetary policy and economic news surprises

on risk aversion and uncertainty are measured. Daily changes in risk aversion and uncertainty

19

(as proxies for unexpected changes to these variables) are regressed, respectively, on the

monetary policy surprises based on high-frequency futures (using the “tight” window shocks)

15

and the four monthly economic news surprises concerning industrial production (ΔIP), the ISM

index (ΔISM), non-farm payroll and employment (ΔEMP), as described in Section 2.3.

16

The

resulting coefficients (with heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors in brackets) are:

ΔRA

t

= -0.039 + 0.047 ΔMP

t

– 0.005 ΔIP

t

– 0.004 ΔISM

t

– 0.004 ΔEMP

t

(6)

(0.007) (0.020) (0.014) (0.016) (0.017)

ΔUC

t

= -0.009 + 0.013 ΔMP

t

+ 0.002 ΔIP

t

– 0.002 ΔISM

t

– 0.008 ΔEMP

t

(7)

(0.003) (0.010) (0.005) (0.005) (0.011)

The coefficients on the business cycle news surprises are not statistically different from zero and

economically small. However, the responses to the monetary policy surprises are quantitatively

larger and statistically significant at the 5% level for RA and at the 16% level for UC. The

coefficients on ΔMP give us direct evidence on the contemporaneous responses of RA and UC

to structural disturbances in MP. Note that these responses confirm that risk aversion reacts

positively to monetary policy shocks and does so more strongly than uncertainty. By the same

token, we conclude that the contemporaneous responses of RA and UC to a business cycle

shock in our VARs are equal to zero.

In the third step, the estimates of structural responses of RA and UC to monetary policy and

business cycle shocks are used in our VAR analysis. This requires a number of additional

assumptions. In particular, it is assumed that there are no further policy or business cycle shocks

during the month and thus that the monthly shock equals the daily shock identified from high

frequency data. Furthermore, it is assumed that the contemporaneous daily change in risk

aversion and uncertainty identifies the monthly change in unexpected risk aversion and

uncertainty due to these policy and business cycle shocks. Therefore, the high-frequency

regressions effectively yield four coefficients in the A

-1

matrix of our structural VAR. Because

six restrictions in total are needed, two more restrictions are imposed from a Cholesky ordering.

In one identification scheme (Model 1), the imposed restrictions are that both industrial

production and monetary policy do not instantaneously respond to RA; in another scheme, the

same restrictions are imposed on the reaction to UC (Model 2).

17

15

Results for the monetary policy surprises calculated using the “wide” window are very similar.

16

Both the non-farm payroll and the negative of the unemployment surprises are treated as news about employment (ΔEMP) as

they have similar information content. Whenever they come out on the same day (which is mostly the case), they are summed

up.

17

Imposing zero-response restrictions to RA and UC in the BC equation would lead to an under-identified model.

20

4.1.2 IDENTIFICATION USING HIGH-FREQUENCY FED FUNDS FUTURES: RESULTS

Figure 6 presents impulse-responses to monetary policy shocks. Looser monetary policy

(corresponding to a 29 basis points decrease in the real rate) lowers risk aversion on impact and

in the medium run in both models. The maximum impact (at 0.061) is slightly larger and the

duration of the effect (between lags 7 and 17) longer in the model with no contemporaneous

response of the business cycle and monetary policy to UC.

- Figure 6 -

As Panel B shows, a positive shock to the real rate increases uncertainty on impact in the model

with no contemporaneous response of the business cycle and monetary policy to RA. The effect

is positive but not statistically significant in the medium run. In the model with no

contemporaneous response of the business cycle and monetary policy to UC, the positive effect

of the real rate shock on uncertainty is statistically significant on impact and between lags 10-

14, with a maximum impact of 0.059 at lag 14.

Lastly, the impact of monetary policy on industrial production growth is not statistically

significant (Panel C). Note that with different measures for the business cycle, such as

employment, the VAR does produce the expected and statistically significant response of

economic activity to monetary policy.

Because the identifying assumptions on monetary policy shocks have more support in the extant

literature than the assumptions made regarding the business cycle shocks, we also consider a

robustness check in which only the high-frequency responses to monetary policy surprises are

imposed in the monthly VAR. As four additional restrictions are then needed from a Cholesky

ordering to complete identification, the three contemporaneous restrictions in the BC equation

are used (the usual assumption on sluggish adjustment of macro to financial data) and a zero

response by monetary policy to either RA or UC. Results, presented in the Online Appendix

(Figure OA7), confirm that looser monetary policy lowers risk aversion significantly on impact

and in the medium run, with a maximum impact of 0.055 at lag 15 in both models. A positive

shock to the real rate increases uncertainty significantly on impact and between lags 4-36, with a

maximum impact of 0.058 at lag 16 in both models.

Repeating this analysis for the full sample, it is found that all the estimated coefficients in the

second step high frequency regressions are not statistically different from zero, but the effect of

monetary policy shocks on risk aversion is again positive with a t-stat of close to 1. The

21

structural responses from the third step are qualitatively the same but statistically weaker

(Figure OA8 in the Online Appendix).

18

4.2 IDENTIFICATION USING MONTHLY FED FUNDS FUTURES

In this section, the approach of Bernanke and Kuttner (2005) is adopted to study the dynamic

response of risk aversion and uncertainty to monetary policy. The key feature of their approach

is the calculation of a monthly monetary policy surprise using Federal funds futures contracts.

This variable identifies the monetary policy shock and is included in the VAR as an exogenous

variable. The endogenous variables in the VAR are RA, UC and the log difference of industrial

production (DIPI).

Figure 7 presents impulse-responses to “cleansed” monetary policy shocks

19

for the pre-crisis

sample and Figure OA9 in the Online Appendix for the full sample. The results generally

confirm that monetary policy tightening has a positive impact on both risk aversion and

uncertainty, and have the expected negative effect on industrial production. However, the results

are less strong statistically than under our other identification schemes.

- Figure 7 -

A one standard deviation negative shock to the “cleansed” surprise, equivalent to 8.6 basis

points, decreases RA on impact by 0.061 and UC by 0.054. The IRFs are significant on impact

at the 80% confidence level for RA and at the 70% level for UC. These results are robust to the

use of alternative business cycle indicators (non-farm employment and the ISM index).

18

To identify the monthly VAR, the two zero responses to monetary policy surprises from the second step are imposed, plus the

four Cholesky restrictions as described above. Imposing the four zero coefficients from the second step would render the VAR

under-identified.

19

The monetary policy surprise is standardized by subtracting the mean and dividing by the standard deviation.

22

5 CONCLUSIONS

A number of recent studies point at a potential link between loose monetary policy and

excessive risk-taking in financial markets. Rajan (2006) conjectures that in times of ample

liquidity supplied by the central bank, investment managers have a tendency to engage in risky,

correlated investments. To earn excess returns in a low interest rate environment, their

investment strategies may entail risky, tail-risk sensitive and illiquid securities (“search for

yield”). Moreover, a tendency for herding behavior emerges due to the particular structure of

managerial compensation contracts. Managers are evaluated vis-à-vis their peers and by

pursuing strategies similar to others, they can ensure that they do not under perform. This

“behavioral” channel of monetary policy transmission can lead to the formation of asset prices

bubbles and can threaten financial stability. Yet, there is no empirical evidence on the links

between risk aversion in financial markets and monetary policy.

This article has attempted to provide a first characterization of the dynamic links between risk,

uncertainty and monetary policy, using a simple vector-autoregressive framework. Implied

volatility is decomposed into two components, risk aversion and uncertainty, and the

interactions between each of the components and monetary policy are studied under a variety of

identification schemes for monetary policy shocks. It is consistently found that lax monetary

policy increases risk appetite (decreases risk aversion) in the future, with the effect lasting for

more than two years and starting to be significant after about nine months. The effect on

uncertainty is similar but the immediate response of uncertainty to monetary policy shocks in

high frequency regressions is weaker than that of risk aversion. Conversely, high uncertainty

and high risk aversion lead to laxer monetary policy in the near-term future but these effects are

not always statistically significant. These results are robust to controlling for business cycle

movements. Consequently, our VAR analysis provides a clean interpretation of the stylized

facts regarding the dynamic relations between the VIX and the monetary policy stance depicted

in Figure 1. The primary component driving the co-movement between past monetary policy

stance and current VIX levels (first column of Figure 1) is risk aversion but uncertainty also

reacts to monetary policy. Both components of the VIX lie behind the negative relation in the

opposite direction (second column of Figure 1) but statistical confidence in this structural link is

smaller.

We hope that our analysis will inspire further empirical work and research on the exact

theoretical links between monetary policy and risk-taking behavior in asset markets. A recent

literature, mostly focusing on the origins of the financial crisis, has considered a few channels

that deserve further scrutiny. Adrian and Shin (2008) stress the balance sheets of financial

intermediaries and repo growth; Adalid and Detken (2007) and Alessi and Detken (2011) stress

23

the buildup of liquidity through money growth; and Borio and Lowe (2002) emphasize rapid

credit expansion.

20

Recent work in the consumption-based asset pricing literature attempts to

understand the structural sources of the VIX dynamics (see Bekaert and Engstrom (2013),

Bollerslev, Tauchen and Zhou (2009), Drechsler and Yaron (2011)). Yet, none of these models

incorporates monetary policy equations. In macroeconomics, a number of articles have

embedded term structure dynamics into the standard New-Keynesian workhorse model

(Bekaert, Cho, Moreno (2010), Rudebusch and Wu (2008)), but no models accommodate the

dynamic interactions between monetary policy, risk aversion and uncertainty, uncovered in this

article.

The policy implications of our work are also potentially important. Because monetary policy

significantly affects risk aversion and uncertainty and these financial variables may affect the

business cycle, we seem to have uncovered a monetary policy transmission mechanism missing

in extant macroeconomic models. Fed chairman Bernanke (see Bernanke (2002)) interprets his

work on the effect of monetary policy on the stock market (Bernanke and Kuttner (2005)) as

suggesting that monetary policy would not have a sufficiently strong effect on asset markets to

pop a “bubble” (see also Bernanke and Gertler (2001), Gilchrist and Leahy (2002), and

Greenspan (2002)). However, if monetary policy significantly affects risk appetite in asset

markets, this conclusion may not hold. If one channel is that lax monetary policy induces excess

leverage as in Adrian and Shin (2008), perhaps monetary policy is potent enough to weed out

financial excess. Conversely, in times of crisis and heightened risk aversion, monetary policy

can influence risk aversion and uncertainty in the market place, and therefore affect real

outcomes.

20

In fact, the effects of repo, money and credit growth on our results were considered by including them in a four-variable VAR

together with RA, UC, and RERA (replacing the BC variable). We consistently found that the direct effect of monetary policy on

risk aversion and uncertainty we uncovered in our benchmark VARs is preserved.

24

REFERENCES

Adalid, R., Detken, C., 2007. Liquidity Shocks and Asset Price Boom/Bust Cycles. ECB

Working Paper No. 732.

Adrian, T., Shin, H. S., 2008. Liquidity, Monetary Policy, and Financial Cycles. Current Issues

in Economics and Finance 14 (1), Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Alessi, L., Detken, C., 2011. Quasi Real-time Early Warning Indicators for Costly Asset Price

Boom/bust Cycles: A Role for Global Liquidity. European Journal of Political Economy 27(3),

520-533.

Altunbas, Y., Gambacorta, L., Marquéz-Ibañez, D., 2010. Does Monetary Policy Affect Bank

Risk-taking? ECB Working Paper No. 1166.

Andrews, D.W.K., 1993. Tests for Parameter Instability and Structural Change with Unknown

Change Point. Econometrica 61(4), 821-56.

Andrews, D.W.K., 2003. End-of-Sample Instability Tests. Econometrica 71(6), 1661-1694.

Baker, M., Wurgler, J., 2007. Investor Sentiment in the Stock Market. Journal of Economic

Perspectives 21, 129-151.

Bakshi, G., Madan, D., 2000. Spanning and Derivative-Security Valuation. Journal of Financial

Economics 55 (2), 205-238.

Bakshi, G., Kapadia, N., Madan, D., 2003. Stock Return Characteristics, Skew Laws, and

Differential Pricing of Individual Equity Options. Review of Financial Studies 16 (1), 101-143.

Bekaert, G., Cho, S., Moreno, A., 2010. New Keynesian Macroeconomics and the Term

Structure. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 42 (1), 33-62.

Bekaert, G., Engstrom, E., 2013. Asset Return Dynamics under Habits and Bad Environment-

Good Environment Fundamentals. Working paper, Columbia GSB.

Bekaert, G., Engstrom, E., Xing, Y., 2009. Risk, Uncertainty, and Asset Prices. Journal of

Financial Economics 91, 59-82.

Bekaert, G., Hoerova, M., 2013. The VIX, the Variance Premium and Stock Market Volatility.

NBER Working Paper No. 18995, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Bernanke, B., 2002. Asset-Price ‘Bubbles’ and Monetary Policy. Speech before the New York

chapter of the National Association for Business Economics, New York, New York, October

15.

Bernanke, B., Gertler, M., 2001. Should Central Banks Respond to Movements in Asset Prices?

American Economic Review 91 (May), 253-57.

Bernanke, B., Kuttner, K.N., 2005. What Explains the Stock Market’s Reaction to Federal

Reserve Policy? Journal of Finance 60 (3), 1221-1257.

Bernanke, B., Mihov, I., 1998a. Measuring Monetary Policy. Quarterly Journal of Economics

113 (3), 869-902.

25

Bernanke, B., Mihov, I., 1998b. The Liquidity Effect and Long-run Neutrality. Carnegie-

Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 49 (1), 149-194.

Blanchard, O., Quah, D., 1989. The Dynamic Effects of Aggregate Demand and Supply

Disturbances. American Economic Review 79 (4), 655-73.

Bloom, N., 2009. The Impact of Uncertainty Shocks. Econometrica 77 (3), 623-685.

Bloom, N., Floetotto, M., Jaimovich, N., 2009. Real Uncertain Business Cycles. Working paper,

Stanford University.

Bollerslev, T., Tauchen, G., Zhou, H., 2009. Expected Stock Returns and Variance Risk Premia.

Review of Financial Studies 22 (11), 4463-4492.

Borio, C., Lowe, P., 2002. Asset Prices, Financial and Monetary Stability: Exploring the Nexus.

BIS Working Paper No. 114.

Borio, C., Zhu, H., 2008. Capital Regulation, Risk-Taking and Monetary Policy: A Missing

Link in the Transmission Mechanism? BIS Working Paper No. 268.

Breeden, D., Litzenberger, R., 1978. Prices of State-contingent Claims Implicit in Option Prices,

Journal of Business 51 (4), 621-651.

Britten-Jones, M., Neuberger, A., 2000. Option Prices, Implied Price Processes, and Stochastic

Volatility. Journal of Finance 55, 839-866.

Campbell, J. Y, Cochrane, J., 1999. By Force of Habit: A Consumption Based Explanation of

Aggregate Stock Market Behavior. Journal of Political Economy 107 (2), 205-251.

Carr, P., Wu, L., 2009. Variance Risk Premiums. Review of Financial Studies 22 (3), 1311-

1341.

Chicago Board Options Exchange, 2004. VIX CBOE Volatility Index. White Paper.

Christiano, L.J., Eichenbaum, M., Evans, C.L., 1996. The Effects of Monetary Policy Shocks:

Evidence from the Flow of Funds. The Review of Economics and Statistics 78(1), 16-34.

Christiano, L.J., Eichenbaum, M., Evans, C.L., 1999. Monetary Policy Shocks: What Have We

Learned and to What End? In: J. B. Taylor and M. Woodford (eds.), Handbook of

Macroeconomics, Vol. 1A, 65-148, North-Holland.

Coudert, V., Gex, M., 2008. Does Risk Aversion Drive Financial Crises? Testing the Predictive

Power of Empirical Indicators. Journal of Empirical Finance 15, 167-184.

D’Amico, S., Farka, M., 2011. The Fed and the Stock Market: An Identification Based on

Intraday Futures Data. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics 29(1), 126-137.

Drechsler, I., 2009. Uncertainty, Time-Varying Fear, and Asset Prices. Journal of Finance,

forthcoming.

Drechsler, I., Yaron, A., 2011. What’s Vol Got to Do with It. Review of Financial Studies

24(1), 1-45.

Ehrmann, M., Fratzscher, M., 2004. Exchange Rates and Fundamentals: New Evidence from

Real-time Data. ECB Working Paper No. 365.

26

Faust, J., Swanson, E., Wright, J., 2004. Identifying VARs Based on High Frequency Futures

Data. Journal of Monetary Economics 51(6), 1107-1131.

Gilchrist, S., Leahy, J.V., 2002. Monetary Policy and Asset Prices. Journal of Monetary

Economics 49 (1), 75-97.

Gilchrist, S., Zakrajšek, E., 2012. Credit Spreads and Business Cycle Fluctuations. American

Economic Review 102(4), 1692-1720.

Greenspan, A., 2002. Economic Volatility. Speech before a symposium sponsored by the

Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, August 30.

Gürkaynak, R. S., Sack, B., Swanson, E., 2005. Do Actions Speak Louder Than Words? The

Response of Asset Prices to Monetary Policy Actions and Statements. International Journal of

Central Banking 1 (1), 55-92.

Ioannidou, V.P., Ongena, S., Peydró, J.-L., 2009. Monetary Policy, Risk-Taking and Pricing:

Evidence from a Quasi Natural Experiment. European Banking Center Discussion Paper No.

2009-04S.

Jiménez, G., Ongena, S., Peydró, J.-L., Saurina, J., 2009. Hazardous Times for Monetary

Policy: What do Twenty-Three Million Bank Loans Say About the Impact of Monetary Policy

on Credit Risk-taking? Econometrica, forthcoming.

King, R., Watson, M.W., 1992. Testing Long Run Neutrality. NBER Working Papers No. 4156,

National Bureau of Economic Research.

Kuttner, K.N., 2001. Monetary Policy Surprises and Interest Rates: Evidence from the Fed

Funds Futures Market. Journal of Monetary Economics 47 (3), 523-544.

Maddaloni, A., Peydró, J.-L., 2011. Bank Risk-Taking, Securitization, Supervision, and Low

Interest Rates: Evidence from the Euro Area and U.S. Lending Standards. Review of Financial

Studies 24(6), 2121-2165.

Newey, W., West, K., 1987. A Simple, Positive Semi-definite, Heteroskedasticity and

Autocorrelation Consistent Covariance Matrix. Econometrica 55(3), 703-708.

Popescu, A., Smets, F., 2009. Uncertainty, Risk-taking and the Business Cycle in Germany.

CESifo Economic Studies 56(4), 596-626.

Rajan, R., 2006. Has Finance Made the World Riskier?” European Financial Management 12

(4), 499-533.

Rigobon, R., Sack, B., 2003. Measuring the Reaction of Monetary Policy to the Stock Market.

Quarterly Journal of Economics 118 (2), 639-669.

Rigobon, R., Sack, B., 2004. The Impact of Monetary Policy on Asset Prices. Journal of

Monetary Economics 51 (8), 1553-1575.

Rubio-Ramírez, J.F., Waggoner, D.F., Zha, T., 2010. Structural Vector Autoregressions: Theory

of Identification and Algorithms for Inference. Review of Economic Studies 77(2), pp 665-696.

Rudebusch, G.D., 2009. The Fed’s Monetary Policy Response to the Current Crisis. The Federal

Reserve Bank of San Francisco Economic Letter, May 2009.

27

Rudebusch, G.D., Wu, T., 2008. A Macro-Finance Model of the Term Structure, Monetary

Policy and the Economy. Economic Journal 118 (530), 906-926.

Sims, C.A., 1980. Macroeconomics and Reality. Econometrica 48(1), 1-48.

Sims, C.A., 1998. Comment on Glenn Rudebusch’s “Do measures of monetary policy in a VAR

make sense.” International Economic Review 39(4), 933-941.

Sims, C.A., Zha, T., 1999. Error Bands for Impulse Responses. Econometrica 67(5), 1113-1155.

Taylor, J. B., 1993. Discretion Versus Policy Rules in Practice. Carnegie-Rochester Conference

Series on Public Policy 39, 195-214.

Thorbecke, W., 1997. On Stock Market Returns and Monetary Policy. Journal of Finance 52

(2), 635-654.

Whaley, R.E., 2000. The Investor Fear Gauge. Journal of Portfolio Management, Spring, 12-17.

Wright, J. H., 2012. What does Monetary Policy do to Long-Term Interest Rates at the Zero

Lower Bound? Economic Journal 122 (564), F447-F466.

28

TABLES AND FIGURES

FIGURE 1: CROSS-CORRELOGRAM LVIX RERA

Notes: The first column presents the (lagged) cross-correlogram between the log of the VIX (LVIX) and past values of the real

interest rate (RERA). The second column presents the (lead) cross-correlogram between LVIX and future values of RERA. Dashed

vertical lines indicate 95% confidence intervals for the cross-correlation. The third column presents the cross-correlation values. The

index i indicates the number of months either lagged or led for the real interest rate variable. The sample period is January 1990 –

July 2007.

29

TABLE 1: DESCRIPTION OF VARIABLES

Name

Label

Description (source)

Conditional variance

Fitted values from the projection in eq. (1)

Consumer price index

CPI

Consumer price index, all items

Dividend yield

Dividend yield of the Standard & Poor 500

index

Fed funds rate

FED

Fed funds target rate

Implied variance VIX

2

Squared implied volatility of options on

the S&P500 index, VIX

2

/ 12

(Log of) Implied volatility (L)VIX

(Log of ) implied volatility of options on

the S&P500 index, (Log) [VIX /

12

]

(Growth of) Industrial production (D)IPI

Log (difference of) total industrial

production index

ISM index

ISM

ISM Purchasing Managers index

M1 money aggregate growth

M1

Month-on-month growth of M1

(Growth of) Non-farm employment

(D)EMP

Log (difference of) non-farm employment

Producer price index PPI

Producer price index for intermediate

materials

Real interest rate

RERA

FED minus annual CPI inflation rate

Realized variance RVAR

Realized variance computed using squared

5-minute returns

Risk aversion RA

Log (implied variance – conditional

variance)

Three-month T-bill

Secondary market yield

Uncertainty (conditional variance)

UC

Log (conditional variance)

Notes: Monthly frequency, end-of-the-month data (seasonally adjusted where applicable). Unless otherwise mentioned in the text,

the data are from Thomson Datastream.

30

FIGURE 2: VIX

2

DECOMPOSITION INTO UNCERTAINTY AND RISK AVERSION

Panel A: Conditional variance (“uncertainty”)

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

1990m1

1991m1

1992m1

1993m1

1994m1

1995m1

1996m1

1997m1

1998m1

1999m1

2000m1

2001m1

2002m1

2003m1

2004m1

2005m1

2006m1

2007m1

2008m1

2009m1

2010m1

Gulf War I

Mexican

Crisis

Asian

Crisis

Russian / LTCM

Crisis

Corporate

Scandals

Low

Uncertainty

Lehman

Aftermath

Euro Area

Debt Crisis

Gulf War I

Mexican

Crisis

Asian

Crisis

Russian / LTCM

Crisis

Corporate

Scandals

Low

Uncertainty

Lehman

Aftermath

Euro Area

Debt Crisis

09/11

Panel B: Difference between implied and conditional variance (“risk aversion”)

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

1990m1

1991m1

1992m1

1993m1

1994m1

1995m1

1996m1

1997m1

1998m1

1999m1

2000m1

2001m1

2002m1

2003m1

2004m1

2005m1

2006m1

2007m1

2008m1

2009m1

2010m1

Gulf War I

Mexican

Crisis

Asian

Crisis

Russian / LTCM

Crisis

Corporate

Scandals

High Risk

Appetite

Lehman

Aftermath

09/11

Euro Area

Debt Crisis

Notes: Figure 2 presents a decomposition of the squared VIX in the two components (in monthly percentages squared, black lines):

the expected stock market variance (our uncertainty proxy, in Panel A) and the residual, the difference between the squared VIX and

uncertainty (our risk aversion proxy, Panel B). The sample period is January 1990 – August 2010. Grey dashed lines are 90%

confidence intervals.

31

FIGURE 3: STRUCTURAL-FORM IRFS FOR THE 4-VARIABLE VAR (DIPI, RERA, RA, UC)

Panel A: Impulse RERA, response RA

Contemporaneous restrictions

Contemporaneous/long-run restrictions

Panel B: Impulse RA, response RERA

Contemporaneous restrictions

Contemporaneous/long-run restrictions

Panel C: Impulse RERA, response UC

Contemporaneous restrictions

Contemporaneous/long-run restrictions

32

Panel D: Impulse UC, response RERA

Contemporaneous restrictions

Contemporaneous/long-run restrictions

Panel E: Impulse RERA, response DIPI

Contemporaneous restrictions

Contemporaneous/long-run restrictions

Panel F: Impulse DIPI, response RERA

Contemporaneous restrictions

Contemporaneous/long-run restrictions

33

Panel G: Impulse RA, response DIPI

Contemporaneous restrictions

Contemporaneous/long-run restrictions

Panel H: Impulse DIPI, response RA

Contemporaneous restrictions