K.7

Monetary Policy Uncertainty

Husted, Lucas, John Rogers, and Bo Sun

International Finance Discussion Papers

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

Number 1215

October 2017

Please cite paper as:

Husted, Lucas, John Rogers, and Bo Sun (2017). Monetary

Policy Uncertainty. International Finance Discussion Papers

1215.

https://doi.org/10.17016/IFDP.2017.1215

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

International Finance Discussion Papers

Number 1215

October 2017

Monetary Policy Uncertainty

Lucas Husted, John Rogers, and Bo Sun

NOTE: International Finance Discussion Papers are preliminary materials circulated to

stimulate discussion and critical comment. References in publications to International

Finance Discussion Papers (other than an acknowledgment that the writer has had access

to unpublished material) should be cleared with the author or authors. Recent IFDPs are

available on the Web at https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/ifdp/. This paper can be

downloaded without charge from Social Science Research Network electronic library at

http://www.sssrn.com.

Monetary Policy Uncertainty

∗

Lucas Husted

Columbia University

John Rogers

Federal Reserve Board

Bo Sun

Federal Reserve Board

∗

We thank workshop participants at the Bank of England, Central Bank of Ireland, Federal Reserve Board,

Georgetown University, Hong Kong Monetary Authority, International Monetary Fund, Notre Dame, UNC-

Chapel Hill, Oxford-FRBNY conference on Monetary Economics, and FRB-Chicago System Committee Meeting

on Macroeconomics. We thank Scott Baker, Nick Bloom, and Steve Davis for hosting our index on their Economic

Policy Uncertainty website. The views expressed here are solely our own and should not be interpreted as reflecting

the vie w s of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System or of any other person associated with the

Federal Reserve System.

Monetary Policy Uncertainty

Abstract

We construct new measures of uncertainty about Federal Reserve policy actions and their con-

sequences — monetary policy uncertainty (MPU) indexes. We show that, under a variety of

VAR identification schemes, positive shocks to uncertainty about monetary policy robustly raise

credit spreads and r educe output. The effects are of comparable magnitude to those of conven-

tional monetary policy shocks. We evaluate the usefulness of our MPU indexes, and examine

the influence of Fed communicatio n. Our analysis suggests that policy rate normalization that

is accompanied by reduced uncertainty can help neutralize the contractionary effects of the rate

increases themselves.

Keywords: Monetary policy uncertainty, VAR identification, FOMC communication

JEL Cl assifications: E40, E50 .

1 Introduction

As the Federal Reserve poised itself in 2015 to lift off from the zero interest rate policy in

place since 2008, the intentions of monetary policymakers and t he effects of their a ctio ns once

again faced increased scrutiny. Reflecting this monetary policy mise-en-scene, the Financial

Times proclaimed on the day after the Octo ber 2015 Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC)

meeting, “Fed Speaks Plainer English on Rates: A clearer marker has been laid down fo r a

December increase, though divisions remain.” In December 2015, the Federal Reserve lifted the

policy r ate o ff its effective lower bound in a 25 basis point hike that has been repeated four

times since. Although the December 2015 Fed liftoff removed the prevailing uncertainty about

when the Fed would finally raise rates, it is less clear more generally what effect liftoff had on

uncertainty a bout monetary policy, including its transmission (Brainard (2017)). Estimating the

transmission of shocks to monetary policy uncertainty is the focus of this paper.

Recently, there has been a surge of interest in economic policy uncertainty.

1

Baker, Bloo m,

and Davis (2016) develop an index of overall economic policy uncertainty (EPU), including fiscal,

monetary, trade, healthcare, national security, and regulatory p olicies, based on the occurrence of

certain keywords in newspaper coverage. The existing literature on monetary policy uncertainty

per se predominantly utilizes market-based proxies such as implied volatility computed from

interest rate option prices and realized volatility computed from intraday prices of interest rate

futures (Neely (2005) , Swanson (2006), Ba uer (2012), and Chang and Feunou (20 13)).

2

As made

evident below, our measure is complementary to these derivative-based measures but differs in

three important dimensions, because the market-based measures: (1 ) reflect the perception of

only the households participating in the o pt ions market, (2) may have a compo nent driven by

time-varying risk aversion and/or state-dependent marginal utility rather than uncertainty and

(3) are essentia lly all ab out (policy) interest rate uncertainty. Our ana lysis suggests that there

exists a significant degree of uncertainty abo ut monetary policy beyond interest rate fluctuations.

3

1

See references at http://www.policyuncertainty.com/research.htm, as well a s Fischer (2017).

2

Carlson, Craig and Melick (2005) and Emmons, Lakdawala and Neely (2006) go beyond implied volatility

and extract the option-implied probability distribution of future policy rates using federal funds futures options.

3

A related set of papers develops various aspects of uncertainty concerning government policy: Justiniano and

Primiceri (20 08), Bloom (2009 ), Rubio-Ramirez, and Uribe (2 011), Stock and Watson (2012), Bachmann, Elstner,

and Sims (2013), Born, Peter, and Pfeifer (2013), Fernandez-Villave rde, Guerron-Quintana, Kue ster, and Rubio-

Ramirez (20 13), Fernandez-Villaverde, Guerron- Quintana, Nakamura, Sergeyev, and Steinsson (2014), Orlik and

Veldkamp (2014), Creal and Wu (2016), Shoa g and Veuger (201 5), Jurado, Ludvigson, and Ng (2015), and Enge n,

Laubach, and Reifschneider (2015).

1

Our paper is also related to a rapidly g r owing literature using textual analysis to measure

economic variables. The news-based search has been recently adopted to construct new measures

for a br oad economic policy index (Baker, Bloom, and Davis ( 2016)), partisan conflict (Azzi-

monti (2017)), geopolitical risk (Caldara and Iacoviello ( 2017)), and corporate news.

4

A number

of papers use var iables generated from publicly released FOMC document s to study FOMC com-

munication, including Boukus and Rosenberg (2006), Ehrmann and Fratzscher (2007), Meade

and Stasavage (2008), Schonha r dt-Bailey (2013), Acosta and Meade (2014), and Acosta (2015).

We update some of these measures. Our paper suggests that text searches can deliver useful

proxies of uncertainty tracing back decades.

Specifically, we do three things in this paper. First, we construct a news-based index of

monetary policy uncertainty to capture the degree of uncertainty that the public perceives about

central bank policy actions and their consequences. We follow the approach in Baker, Bloom,

and Davis (2016), and highlight some important advantages of ours. We also detail our “human

audit” that assesses the accuracy of our construction approa ch. We focus on the Fed starting in

1985.

5

As documented below, large spikes occurred around the September 11 attacks, the March

2003 invasion of Iraq, prior to the October 2015 FOMC meeting when “liftoff uncertainty” seemed

to have peaked, Br exit, and the November 2016 elections.

Second, we evaluate the role of MPU in the monetar y policy transmission mechanism, esti-

mating the effect of shocks to monetary policy uncertainty in VARs utilizing several different

approaches to identification. We examine cases in which the identified MPU shock is by construc-

tion orthogonal to monetary policy shocks. We find that positive shocks to MPU raise credit

spreads and lower output with about the same dynamic pattern as contractionary monetary

policy shocks found in, e.g., Gertler and Karadi (2015).

Last, we provide further discussion that facilitates a better understanding of what our MPU

index captures. We examine co-movements of our index with several alternative proxies. Ours

fluctuates substantially during the period when policy rates were at the effective lower bound,

unlike most competing measures. We investigate whether our MPU index is influenced by insti-

tutional measures of central bank po licy actions such as voting behavior and newly-constructed

4

For example, Davis, Piger, and Sedor (2006), Tetlock (2007), Engelberg (2008), Tetlock, Saar-Tsechansky

and Macskassy (2008), Demer s and Vega (2010), Hoberg and Phillips (2010), Feldman, Govindaraj, Livnat and

Segal (2010), and Loughran and McDonald (2011).

5

In Husted, Rogers, and Sun (2016b), we construct these indexes for the EC B and central banks of Canada,

England, and Japan.

2

measures of FOMC communication. We wrap up by linking the discussion to the related theo-

retical literature.

2 Measuring Monetary Policy Uncertainty

2.1 Construction

Our a pproach to constructing the MPU index is to track the frequency of newspaper articles

related to monetary policy uncertainty. Using the ProQuest Newsstand and historical archives,

we construct the index by searching for keywords related to monetary policy uncertainty in maj or

newspapers. We search for articles containing the triple of (i) “uncertainty” or “uncertain,” (ii)

“monetary policy(ies)” or “interest rate(s)” or “Federal fund(s) rate” or “Fed fund(s) rate,” and

(iii) “Federal Reserve” or “the Fed” or “Federal Open Market Committee” or “FOMC”. We do

this for every day’s issue of the Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, and New York Times.

Importantly, we control for the changing volume of total news a rticles over time and the

possibility that some newspapers naturally cover mo netary policy more than others by first

dividing the raw count of identified articles by the total number of news articles mentioning

“Federal Reserve”, or more pr ecisely, any of the words in category (iii), for each newspaper in

a given period. This scaling choice also helps address issues related to time-varying popula rity

and increased coverage of the Fed due t o improved tr ansparency in its communication strategy.

The share of articles is subsequently normalized to have a unit standard deviation for each

newspaper over the sample period. Each of our monetary policy uncertainty indexes is aggregated

by summing the resulting series and scaling them to have a mean of 100 over the sample. We

construct the index at both a monthly frequency a nd a meeting-interval frequency.

We display o ur baseline MPU index in Figure 1. The sample is January 1985 to May 2017.

The index spikes not ably toward the end, especially ar ound the Brexit vote, as well as at the time

of Black Monday, t he September 11 attacks, the March 2003 invasion of Iraq, the lead-up to the

global financial crisis, the Ta per Tantrum, and prio r to the October 2015 FOMC meeting (when

“liftoff uncertainty” seemed to have peaked). Our index thus fluctuates substantially during the

period the Federal Funds ra t e was at the zero lower bound.

6

6

Consistent with the larg e spike in March 2003, Bernanke (2015) recalls, “U.S. forc es had invade d Iraq a few

days before the (March 2003) meeting. Businesses and hous eholds were reluctant to invest or borrow until they

saw how the invasion would play out. My c olleagues and I were also uncertain about the economic consequences of

the war, especially its effect o n energy prices. At Greenspan’s urging, we decided to wait before considering further

3

We examine the sensitivity of our baseline index by considering several adjustments t o its

construction. In one refinement, we na r row our search to articles in which the word uncer-

tainty/uncertainties is in close proximity to Federal Reserve or monetary policy. Specifically,

we restrict “uncertainty” or “uncertaint ies” to be within either 5, 10, or 20 words of the phrase

“Federal Reserve” or “The Fed” or “monetary policy.” In order to better understand the trade-

offs associated with using the proximity refinement and as part of a more general auditing o f our

automated search, we extracted and read a randomly selected sample of the search results (see

Appendix A). The proximity search does appropriately filter out articles that mention all the

keywords but do not really discuss monetary policy uncertainty per se.

7

The t rade-off, however,

is that the proximity search misses articles that discuss issues related to monetary policy uncer-

tainty but have a somewhat large gap between keywords.

8

We conclude from these readings that

the proximity search has smaller type II error but greater type I error relative to the baseline

strategy, as it filters out more of both “false” articles a nd “correct” articles. The correlat ion

between the baseline index and that constructed using the 10-word proximity search is 0.83 ( see

Husted, Rogers, and Sun (2016a)).

2.2 Human auditing

To address concerns about automated news-based computer search, we conduct an audit based on

human readings. We begin by reading and coding rando mly-selected 6000 articles and construct a

human index based on the share of articles discussing high or rising monetary policy uncertainty.

To concentrate on a r ticles that are likely relevant, the r andom samples we draw a r e from the

set of articles that meet our criterion (iii), that is, containing “Federal Reserve” o r “t he Fed”

or “Federal Open Market Committee” or “FOMC”. We compare the evolution of t he human

index with the computer-automated index, including calculating the Type II error rate. We also

cha r acterize t he nature of monetary policy uncertainty, quantifying the number of articles on

action. In our post-meeting sta tement, we said uncertainty was so high that we couldn’t usefully characterize

the near-term course of the econo my or monetary policy. That unprecedented assertion probably added to the

public’s angst about the economy.”

7

For example, in articles tha t mention monetar y p olicy or interest rate, “uncertainty” shows up in sentences

like the following: “Concerns over Europe have also intensified, as political upheaval has bred uncertainty over

whether the euro zone will be able to implement controver sial austerity measures.”

8

With our 10-word search, for example, an article with the following sentence was not counted: “That the

Fed can, if it chooses, intervene witho ut limit in any credit market — not only mortgage-ba cked securities but

also securities backed by automobile loans or student loans — creates more uncertainty and raises questions

about w hy an independent agency of government should have such power.”

4

uncertainty concerning Fed actions versus uncertainty about the consequences of those actions.

We then read an additional 1500 randomly-selected articles contained in our computer-automated

MPU index in order to estimate the Type I error rate associated with our baseline MPU index.

Our MPU index shows a remarkably high correlation with the index constructed by human

intelligence, and its Type I and Type II error rates are reasonably small and do no t exhibit large

time-series variation.

2.2.1 A human index

Each mont h the newspapers used to construct our MPU index contain 30,000 articles. O f these,

0.17% meet our computer-automated criteria to be included in the MPU index. We la bel this

set (M). In constructing our human index, we restrict our reading to articles containing one of

the category (iii) words: “Federal Reserve” or “the Fed” or “Federal Open Market Committee”

or “FOMC”. This set, labelled (E), accounts for about 2% of the universe of newspaper articles.

We choose this set (E) to draw articles from because (i) a pilot audit (human reading of 300

articles) suggests that the ment ion of Fed is at the heart of relevant discussions, significantly

more so than the mention of monetary policy, for example; and (ii) the human index can also be

normalized in a way consistent with the computer-generated index, i.e., scaled by the number of

articles in set E, which could help minimize the effect of sampling uncertainty.

We randomly select about 5% of the newspaper ar ticles in set E and read the full text of each

of these 6000 articles.

9

Following a detailed a uditing guideline, we use t ext analytic techniques to

identify phrases that likely indicate true positives as well as those that are likely associated with

false positives. We repeat this process and refine the search words until additional adjustments

bring only minor improvements in the error rates (detailed below). For example, although in

some instances articles use words such as “anxiety” and “fear” to discuss uncertainty related to

monetary policy, including these additional words in the search also generates additional fa lse

positives, which o n balance does not improve our index.

10

9

For details of our sampling technique, please see our audit guide available at:

https://sites.google.com/site/bosun09/monetary-policy-uncertainty-index.

10

In our pilot human audit, we notice d fo r instance that articles in the 1980s and early 1990s use “discount

rate” to refer to the monetary policy instrument, while such reference diminished completely in recent years. In

addition, we see some articles using words such as “anxiety” and “fear” to discuss uncertainty related to monetary

policy. With this in mind, we produced an “MPU 2.0” adding the following words in categ ory (i) of our search:

concern(s), or concerned or fear(s) or nervous or worry (worries) or spec ulate(s) or sca re(s) or scared. We also

added a proximity co nstraint that word(s) in category (i) must be within 10 words of those in category (ii) or

(iii). MPU 2.0 shows a significantly lower correlation with the human index than does o ur baseline index.

5

An article is coded as 1 if it contains references to hig h or rising uncertainty in monetary

policy actions and/or their consequences. Articles are coded as -1 if they contain references to low

or declines in such uncertainty, and 0 if the article contains no references to relevant uncertainty.

About 26 percent of the articles in set E are coded as 1 from our reading.

11

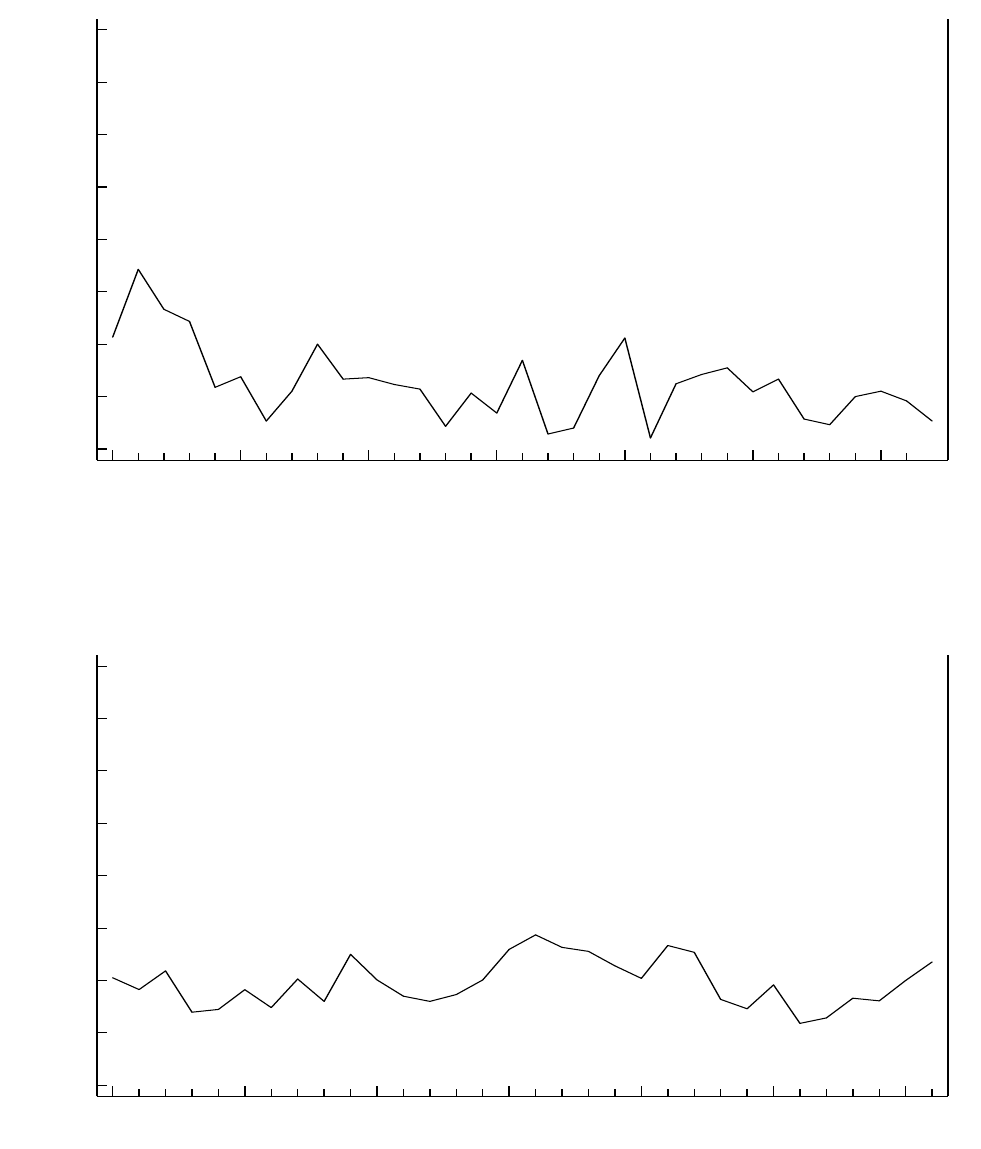

Figure 2 displays

the human index against the computer-generated MPU index. The correlation is high, at 0.84.

2.2.2 The nature of monetary policy uncertainty

In the second stage of our audit, we randomly select 1500 articles from those contained in our

MPU index. This accounts for over 10% of set M. Among those articles that are coded as 1,

we code an article as “A” if the discussion p ertaining to monetary policy uncertainty is on the

Fed’s actions a nd as “B” if on the consequences of the Fed’s actions. When an article discusses

both, it is coded as “A a nd B”. We find that our index mainly captures uncertainty about

the Fed’s actions: among the true p ositives, only 10.6% are about consequences of Fed actions

(including the ones on both actions and consequences). The remainder are about uncertainty

concerning Fed actions themselves. During the earlier part of the Zero Lower Bound period

(ZLB), newspaper ar ticles were mostly discussing uncertainty about economic implications of

ZLB, while uncertainty about Fed actions took center stag e in the 2013 Taper Tantrum and in

the second half o f 201 5.

2.2.3 Typ e I vs Type II error

To furt her evaluate the statistical properties of our MPU index, we analyze the rate of Type I

(false po sitives) and Type II (false negatives) errors. From our sample reading of (1500) articles

belonging to the benchmark, computer-generated MPU index, about 85 percent a r e classified as

mentioning high or rising uncertainty related to monetary policy, judged by human intelligence.

The month-to-month variation of this fraction of false positives is minimal, alleviating concerns

about time-varying bia ses. One might be particularly concerned about articles on low o r declining

monetary policy uncertainty getting included in the MPU index. In our sample, only 3.7% of

the articles in set M (those included in t he computer-generated MPU index) discuss falling

uncertainty. Figure 3 shows the time-series variation in the Type I error rate. The error rate

is quite flat, and clearly uncorrelated with our MPU index itself or with other macroeconomic

11

Human reading is done either by one of the authors or a Fed research assistant.

6

variables.

Given the time-varying writing styles in newspapers, we are mindful that the ratio of false

negatives could also vary systematically over t ime. We thus calculate the Type II error every

month as follows. We first identify the articles in our sample o f set E tha t would be included in

the computer-automated index (set M, which is a strict subset of E) , i.e., containing the triple of

key words we search for. In the remaining sample (set E − M), we count the number of articles

that contain r eferences to high or rising monetary policy uncertainty, which gives us the Type

II error rate. Our Type II error rate is on average 0.24 per year, with a standard deviation of

0.05. This indicates that false negatives are also not a major concern for our index. Figure 4

plots the Type II error rate, which is also very flat and uncorrelated with our MPU index and

other macroeconomic indicators.

3 Response of MPU t o Mo netary Policy Shocks

To set the stage for studying the transmission of monetary policy uncertainty shocks, we begin

by estimating the effects of monetary policy shocks. This provides a benchmark f or gauging the

importance of MPU shocks. Our strategy is t o take a VAR model t hat is considered conventional

in the literature and add MPU to it (see Ramey (2015) for a recent review). Since o ur sample

period includes the ZLB, our disturbances of interest also include shocks to forward guidance.

Thus, we choose as benchmark Gertler and Karadi (2015) (hereafter GK) and fo llow them in

undertaking a high frequency identification of the policy shocks.

12

.

Let Y

t

be a vector o f economic and financial var iables, A and C

j

∀j ≥ 1 conformable coeffi-

cient matrices, and ǫ

t

a vector of structural shocks. The general structural form of the VAR we

consider is given by

AY

t

=

X

j

C

j

Y

t−j

+ ǫ

t

(1)

Multiplying each side by A

−1

yields the reduced form VAR

12

In their abstract, GK note of their findings, “Shocks produce responses in output and inflation that are typical

in monetary VAR analysis”. See also Stock and Watson (2012) and Rogers, Scotti, and Wright (2016) (RSW).

7

Y

t

=

X

j

B

j

Y

t−j

+ u

t

, (2)

where u

t

= Sǫ

t

is the reduced f orm shock, with B

j

= A

−1

C

j

, S = A

−1

.

Let s denote the column in matrix S corresponding to the impact on each element of t he

vector of reduced form residuals u

t

of the structural shock ǫ

t

. To compute the impulse responses

to a structural shock, we estimate

Y

t

=

X

j

B

j

Y

t−j

+ sǫ

t

(3)

As is well-known, the necessary timing restriction t hat all the elements of s are zero except

the one that corresponds to the policy indicator of interest is in general problematic, especially

when financial variables are included in the VAR such as in our application and GK’s. The

external instrument approach is well- suited to address this problem. Denoting Z

t

as a vector

of instrumental variables and ǫ

q

t

a vector structural shocks other than the p olicy shock, the

identificatio n approach requires tha t :

E [Z

t

ǫ

′

] = ψ, E

h

Z

t

ǫ

q

′

i

= 0 (4)

That is, Z

t

must be correlated with ǫ

t

, the structural shock o f interest, but ort hogonal to all

of the other sho cks.

To estimate the elements in s, we follow GK and proceed as f ollows. First, estimate u

t

from

the ordinary least squares regression of the r educed fo r m VAR (2). Second, let u

t

be t he reduced

form residual from the equation for the policy indicator of interest and let u

q

t

be the reduced

form r esidual from the equation for variables q other than the policy indicator. Let s

q

∈ s be

the response of u

q

t

to a unit increase in the policy shock ǫ

t

. Then obtain an estimate of the ratio

s

q

/s from the two stage least squares regression of u

q

t

on u

t

, using the instrument set Z

t

.

We follow GK in employing high frequency measures of policy surprises as external instru-

ments, in order to identify the structural monetary policy shocks, now in the presence of monetary

policy uncertainty. To isolate the impact o f news about monetar y policy, the surprises in fu-

tures rates are measured within a tight window a round the FOMC decision. The key identifying

assumption is that news about the rest of the economy within that window on FOMC day is

8

orthogonal to t he policy surprise. That is, surprises in Fed Funds futures o n FOMC dates are

orthogonal to within-window movements in other shocks affecting economic and financial vari-

ables. One additional benefit o f this approa ch, as illustrated in GK and RSW among others, is

that the policy surprise measure can include shocks to forward guidance.

13

This is accomplished

by incorporating in the instrument set surprises in fed funds futures for contracts that expire at

a subsequent date in the future. These surprises in principle reflect revisions in beliefs on FOMC

dates about the future path of short-term rat es. Following GK, we exploit the HFI approach to

identify exogenous monetary policy surprises and then use a f ull VAR to trace out the dynamic

responses of real and financial variables.

We analyze monthly data over the period 1985:01 to 2015:12. The end point is chosen to

coincide with the precise ending of the ZLB period. The instrument is the surprise in the three

month ahead monthly fed funds f utur es within a 30 minute window of the FOMC announcement,

taken from GK.

14

As a rgued by RSW, among others, during the ZLB period monetary policy was

aimed at rates of longer maturity (through forward guidance and quantitative easing). Thus, to

construct our instrument for updating GK’s results, we splice the interest rate futur es surprises

used in RSW onto those of GK. That is, we use the GK instruments f or 1991 :01–2008:08 and the

RSW instruments for the period 2008:09–2015:12. RSW identify U.S. monetary policy shocks

during the ZLB period using the change in five-year Treasury futures from 15 minutes before

the time of FOMC announcements to 1 hour 45 minutes afterwards on the days of FOMC

announcements (the longer window reflecting the Chair’s press conference, begun in 2011).

As no ted above, our starting point is the baseline model of GK: a VAR that includes the

log industrial production, the log consumer price index, the one-year government bond rate,

and a credit spread, specifically, the Gilchrist and Zakrajsek (GZ) excess bond premium. In

addition, we add monetary policy uncertainty. We follow GK in taking the one-year g overnment

bond rate, rather than the commonly-used Federal Funds rate, as the relevant monetary policy

indicator. As GK argue, using a safe interest rate with a longer maturity than the Fed Funds

rate allows one to consider shocks to forward guidance in the overall measure of monetary policy

shocks: a component of the reduced form VAR residual for the one-year government bond rate

13

Campbell, Evans, Fisher, and Justiniano (2012 ) and Campbell, Fisher, Justiniano, and Melosi (2016) discuss

the c omplications associated with interpreting such s urprises as pure monetary policy shocks. Their focus is on

distinguishing be tween “Delphic” and “Odyssean” forward guidance.

14

GK establish this as a valid e xternal instrument for the one-year government bond rate with the conventional

F-test statistic well above 10.

9

is a monetary policy shock that includes exogenous surprises not only to the current Fed Funds

rate but also exogenous surprises in the forward guidance about the path of future rates.

The GZ excess bond premium is the component of the remaining spread between an index of

rates of return on corporate securities and the rate on a government bond of a similar maturity

after the default risk component is removed. GZ a nd GK show that the excess b ond premium

has stro ng forecasting ability f or economic activity, outperforming every other financial indicator

and thus providing a convenient summary of much of the information from varia bles left out of

the VAR t hat may be relevant to economic activity.

Figure 5 displays t he impulse responses to an identified monetary policy shock in the five-

variable VAR estimated over the period 1985:1-2015:12.

15

In each case, the panels report the

estimated impulse responses along with 68 percent confidence bands, computed using bootstrap-

ping methods.

The impulse responses are almost identical t o those reported by GK : a surprise monetary

tightening induces a roughly 25 basis point increase in the one-year government bond rate. There

is a significant decline in industrial production that reaches a trough roughly two years after the

shock. Also consistent with standard theory, there is a very small decline in t he consumer price

index though it is not statistically significant. The excess bond premium increases by 25 basis

points on impact and returns to trend after roughly a year. This increase in the excess bo nd

premium following the monetary policy tightening is consistent with a credit channel effect on

borrowing costs.

Finally, we find no significant response of MPU, suggesting that MPU is largely unaffected

by conventional monetary policy shocks. This result is interesting in its own right and is also

somewhat reassuring: conceptually, our MPU is a “second-moment” variable that should be

mostly orthogonal to t he first-moment movement in monetary policy. Our no-response result,

at a minimum, indicates that our measure of monetary policy uncertainty captures information

that is distinct from what is contained in contemporaneous monetary policy shocks.

4 MPU and Aggregate Economic Activity

We now turn to the central question: how do economic and financial variables respond to exoge-

nous shocks to monetar y policy uncertainty? We do so using several commonly-used identification

15

We replicate GK for their sample period prior to beginning our exercises.

10

methods: Cholesky decompositions, sign restrictions, and external instruments. Our estimates

consistently indicate that monetary policy uncertainty shocks lead to weaker economic perfor-

mance and t ightened credit costs. Furthermore, comparison with the results above indicates that

the estimated cont ractionary effects of positive MPU shocks are as large as those of monetary

policy tightening shocks.

16

4.1 Cholesky decomposition

We start with the most commonly used identification method, a standard Cholesky decomposi-

tion (Sims (1980)).

17

We assume the f ollowing recursive structure of the VAR:

Y

t

= [ip

t

, cpi

t

, mpu

t

, i

t

, ebp

t

] (5)

Under the assumed ordering, monetary policy uncertainty can have an immediate impact

on the monetary po licy indicator and excess bond pr emium. Innovations in the interest rate

and excess b ond premium do not affect MPU contemporaneously, which is consistent with our

findings in Section 3. Here, we are interested in identifying shocks to MPU and t heir transmission

effects, and we therefore impose as few restrictions as possible: the current specification allows

the policy rate and the excess bond premium to respond simultaneously to MPU, which we

consider plausible given how fina ncial markets work.

18

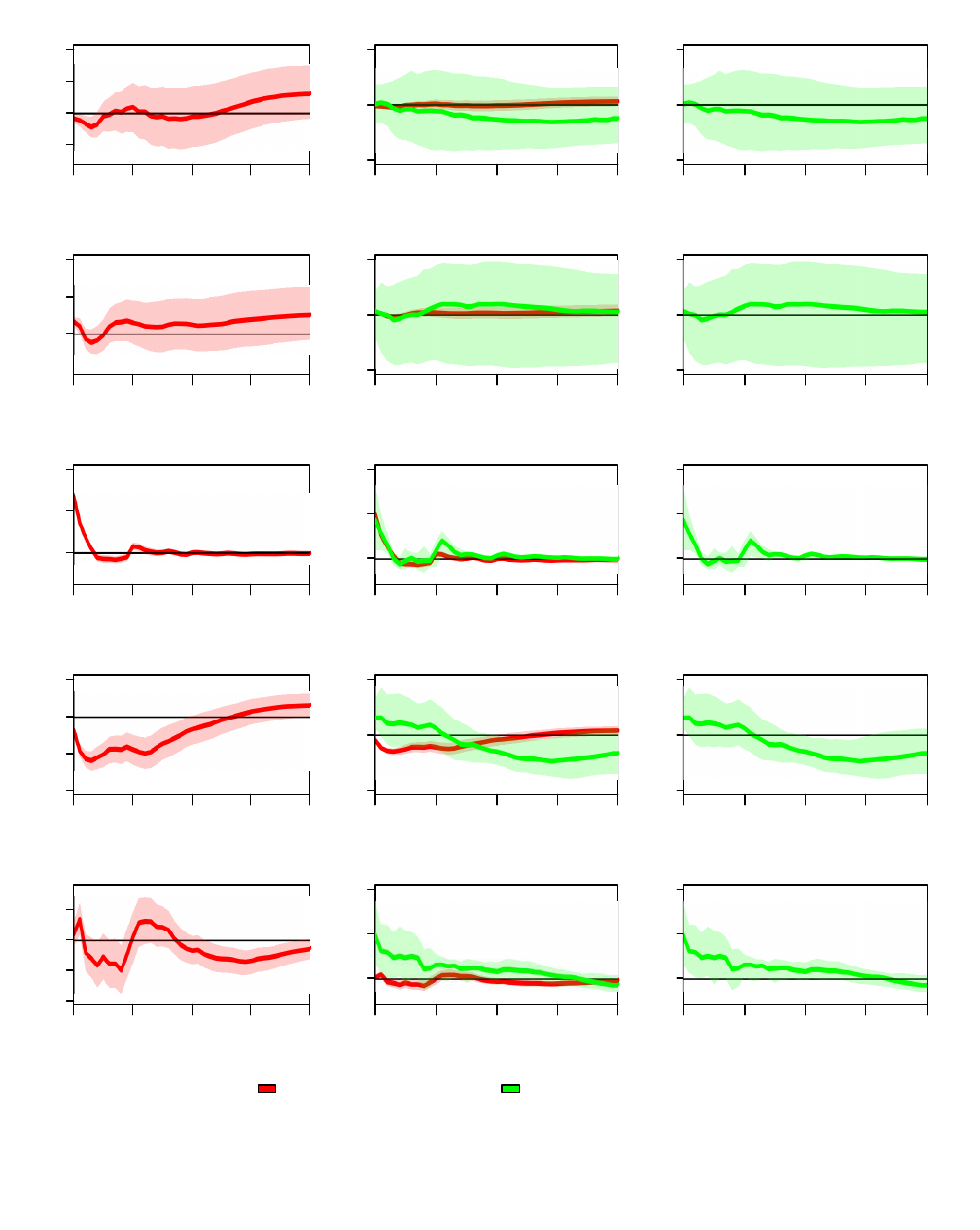

The left panels of Figure 6 show the impulse responses following a one standard deviation

surprise increase in MPU. The sample period is again 1985:01–2015:12. There is a drop in the

one-year government bond rate, perhaps induced by the central bank responding to the increased

uncertainty by lowering the policy r ate. The excess bond premium rises o n impact, suggestive of

increased borrowing costs in response to positive shocks to monetary policy uncertainty. Finally,

despite the loosening of interest rates, industrial output and inflation fall on impact and reach a

trough roughly in month 1 7.

16

In Table 1, we summarize the ma gnitude o f effects from the various VAR identification schemes. Related to

our analysis of this sectio n, and with similar conclusions, Creal and Wu (2016) also exa mine the transmission of

monetary policy uncertainty shocks, using very different uncertainty measures and estimation framework.

17

GK also utilize results from Cholesky decompositions as a comparator. Baker, Bloom, and Davis (2016) rely

exclusively on this identification scheme.

18

We find similar results in Cholesky identifications with MPU o rdered first.

11

4.2 Sign restrictions

The results from the Cholesky decomposition are useful, serving as an easily-replicated com-

parison case, but as is well understood it is necessary to examine robustness to alternative

identificatio n schemes. Faust (1998) and Uhlig (1997, 2005) developed a metho d to incorporate

“reasonableness” of responses to monetar y policy shocks without undercutting scientific inquiry

by imposing sign restrictions on the responses of variables other than the ones whose responses

are the subject of that inquiry.

We follow suit, estimating the five-variable VAR imposing that the one-year rate and excess

bond premium must rise on impact following a one standard deviation surprise increase in MPU.

Thus, we assess the transmission of MPU shocks to output and inflation when the policy indicator

is not allowed to fall (motivated by the ZLB period).

We display impulse responses f or the sign restrictions case in the far right column of Figure

6 and for ease of comparison display the Cholesky and sign restriction cases together in the

middle column. The excess bond premium increases on impact by roughly 20 basis p oints, an

amount that is stat istically significant . The spread remains elevated above 5 basis points for

roughly another year. Compared to the standard Cholesky identification, the declines in indus-

trial production and consumer price index are greater and more persistent under sign restrictions,

although not statistically significant in the case of CPI. This follows conventional reasoning, given

that the interest rate cannot fall.

We note that the relationship between monetary policy uncertainty and interest rate is am-

biguous conceptually. Consider the one-year bond rate to be the expectation o f future (overnight)

policy rates plus a term premium. During the Z L B period, it is likely tha t higher MPU raises

term premiums without affecting expectations of f utur e policy rates and hence raises the one-

year bond rate. Away fr om the ZLB, however, higher MPU could lead to lower interest rates as

exp ected future policy rates fall. We take note of this in discussing the remainder of our results.

19

4.3 External Instruments

We tur n t o estimating the transmission of MPU shocks using the external instruments approach,

described in section 3 for the case of identifying monetary policy shocks. Here, we will use as

19

When we estimate using external instrument over 1994-2015, thereby with a larger fraction of the sample

being ZLB years, the interest rate response to MPU is indeed more positive (compared to the full-sample case

also using external instrument), displayed in Figure F.7 in Appendix F.

12

our instrument the “monetary policy uncertainty surprise”. This is constructed as the change

in uncertainty around FOMC meeting days, orthogonalized with respect to the monetary poli c y

surprise described in section 3. Denote the daily implied volatility on the eighth eurodollar

futures contract σ(ED8)

t

. This is a measure of uncertainty about future monetary policy. We

regress the change in implied volatility from the day before the FOMC meeting to the day of the

meeting on the “spliced monetary policy instrument” of GK/RSW on FOMC meeting days,

20

∆σ(ED8 )

t

= γpolicy surprises

t

+ η

t

.

The r esidual from this regression, η

t

, is the monetary policy uncertainty surprise.

21

This instru-

ment series is monthly. It takes on a value equal to t he uncertainty surprise in months when there

is an FOMC meeting and zero when there is not. The orthog onalization is important because at

the ZLB, a downward shift in the expected path of policy will mechanically lower interest rate

uncertainty. Our approach thus provides valid instruments by using high-frequency data, with

the key identifying assumption that shocks to the economy and monetary policy (within narrow

windows around FOMC announcements) are uncorrelated with the residual.

Figure 7 displays the impulse resp onses estimated using external instruments. Once again,

we observe that positive shocks t o MPU are cont ractionary: there is a fairly rapid decline in IP

which reaches a trough in about 18 months; the EBP remains elevated for over a year befo r e

reverting to trend; the CPI response is insignificant, as in the GK replication analysis, while the

interest rate response eventually becomes negative in order to offset the contractionary effects

on IP and EBP.

Finally, we estimate the external instrument s VAR with the human index replacing the base-

line index. We find very similar results, as noted in the next section.

4.4 Comparison across identification schemes

The VAR analysis suggests that monetary policy uncertainty shocks lead to weaker macroeco-

nomic performance and tightened credit costs. In Table 1, we compare the size of the impulse

20

Note that this amounts to a timing as sumption about MPU and MP shocks, where by the fo rmer are contem-

poraneously uncorrelated with the latter. This seems reasonable on a priori gro unds , and is also buttressed by

our IRFs showing the ins ignificant respons e of MPU to GK monetary policy shocks.

21

This is in the s pirit of Akkaya, Gurkaynak, Kisacikoglu, and Wright (2015). We have tried several mea sures

of high-frequency monetary policy surprises on the right hand side. The se included surprises on instruments at

various horizons from 1-q uarter ahead to 8. All produced essentially the same results. We choose the spliced

GK/RSW instrument for co mparability with the results in the previous section (GK replication).

13

responses to MPU shocks under the various VAR identification schemes we consider. Further-

more, we compare these to the magnitude of the responses to monetary policy shocks in GK and

in our replication and updating of their results. We report responses of MPU, interest rate, IP,

and CPI on impact, at horizon 12, and at its maximum.

4.4.1 Monetary Policy Shocks (magnitude)

The first two columns display results for monetary policy shocks under the external instru-

ments identification for Gertler and Karadi’s VAR in two different sample periods: GK’s original

1979:07–2012:06 and our sample period for estimating MPU shocks 1985 :01–2015:12. In these

cases, MPU is not in the VAR. As seen in row 2, interest rates rise on impact by about 20 basis

points. The CPI does not change much on impact but eventually falls. IP declines following the

contractionary monetary policy shock, with a peak effect occurring around the two-year mark.

Notice t hat the magnitude of t he decline in IP is considerably larger in the updated sample

compared to GK’s initial results. In column 3, we add MPU to the VAR, corresponding to the

case reported in Figure 5. The results are nearly identical to those o f column 2: adding MPU to

the GK VAR has essentially no effect on the transmission of monetary policy shocks.

4.4.2 MPU Shocks (magnitude)

The remaining columns of Table 1 report the effects of MPU shocks. In each case, the shock

is normalized to a rise in MPU of around 36 p oints, approximately one standard deviation.

Comparing columns 4 and 5, the Cholesky and sign restrictions cases depicted in Figure 6, we

see declines in IP and CPI that are equal to or gr eat er than the declines observed in response to

monetary po licy shocks. For example, in the case of sign restrictions, the rise in MPU leads t o

a maximum drop in IP of 1.1 2 percent compared to 1 .11 fo r monetary policy shocks in the five-

variable GK case. Both of these maximum declines occur at around the two year horizon. Notice

from the results at month 12 that the responses to monetary po licy shocks unfold more rapidly

and are shorter-lived than the responses to MPU shocks under Cholesky or sign restrictions.

Turning to the external instruments cases (column 6-8), we see very large contractionary

transmission effects of MPU shocks, estimating either with the baseline MPU index, the human

index, or with baseline MPU index over the sub-sample 1994-2015. The rise in MPU (normalized)

produces a decline in IP that is comparable to the drop observed in response to monetary policy

shocks.

14

5 Further Discussions of MPU

In order to provide a deeper understanding of what our MPU index captures, in this section we

compare our MPU index to alternative measures of monetary policy uncertainty, and examine the

evolutio n o f our index both during FOMC meeting cycles and over the full sample. In addition,

to provide a theoretical underpinning for our VAR results, we illustrate a pot ential transmission

mechanism of monetar y policy uncertainty in an extended version of McKay, Nakamura, and

Steinsson (2016).

5.1 Alternative measures of monetary policy uncertainty

We compare our baseline MPU index to a number of alternative measures that have been used

as proxies for monetary policy uncertainty. The first is from the Federal Reserve Bank of New

York’s Survey of Primary Dealers, which is conducted one week before each FOMC meeting.

The Survey is available beginning in 200 4, and has the appealing feature of a sking resp ondents

to directly report both their forecasted policy rates and their forecast uncertainty. We use the

dealers’ responses to the following question, over the time period for which this question was

relevant and hence asked (i.e., through late 2 012): “Of the possible out comes below (that is, −50

bps, −25 bps, +0 bps, +25 bps, +50 bps), please indicate the percent chance yo u attach to the

indicated policy move at each of the next three FOMC meetings”. To gauge the respondents’

perceived uncertainty regarding monetary policy, we calculate the avera ge within-respondent

standard deviation of forecasted policy rates.

Our baseline MPU index tracks the survey-based uncertainty measure closely prior to 2008

when the effective zero bound was reached, with a correlation of 0.75 for the one-meeting ahead

forecast and progressively slightly less for each of the next two meeting-ahead forecasts (Figure

8). This suggests that news-based search results capture the intensity of concerns over both

near-term and longer-term horizons, with a relatively stronger focus on the near-term.

In the months preceding the actual liftoff in December 2015, it was apparent that a major

component of monetary policy uncertainty centered on the timing o f lift off. We thus also con-

struct from the Primary Dealers Survey a measure of liftoff uncertainty in a manner similar to

the interest rate uncertainty above. The Survey began asking respondents to judg e the likelihood

of liftoff over a pre-defined horizon consisting of 6 - 11 time periods, starting in April 201 0. Our

MPU index moves quite closely with Primary D ealers’ liftoff uncertainty during 2015 (Figure

15

9), consistent with the notion t hat in that year monetary policy uncertainty more generally was

primarily about expectations concerning the timing of liftoff.

Second, we compare our MPU index to two market-based indicators of monetary policy

uncertainty. In Figure 1 0 we display our measure against t he implied volatility of options on

one-year swa p rates (swaptions), taken from Carlston and Ochoa (2016). Note that as the short-

term policy rate approached zero, the market-based indicator fell quickly and remained extremely

low during the ZLB period. This suggests that the market-based measures do not fully capture

monetary policy uncertainty in a broad sense. Episodes such as the Taper Tantrum in 2013

and financial market turmoil prior to the October 2015 FOMC meeting suggest that uncertainty

regarding the timing and pace of policy rate normalization was far from zero. Our MPU measure

is more strongly correlated with one-year swaption volatility, shown above, t han the t en- year (not

shown), reinforcing the notion that our measure captures more o f the near-term course of policy.

In a ddition, we compare our index to the VIX, the stock market options-based implied volatility

measure that has been widely used as a proxy for uncertainty (Bloom, 2009). Our measure of

monetary policy uncertainty is positively correlated with the VIX, but only weakly so.

22

Compared to these measures based on survey data and market volatility, our measure there-

fore has the advantage of (1) being available in countries and during time periods when market or

survey da ta are not available and (2) better capturing uncertainty in periods with unconventional

monetary policy when the policy ra t e is at or near the lower bound.

We also compare our baseline MPU with the Baker, Bloom, and Davis’ (2016) Monetary

Po licy sub-index o f EPU, which is only correlated with our MPU index at 0.46. Our index

construction differs from theirs along three dimensions (indexes are displayed in Figure 1 1).

First, they use the Access World News database of over 2,000 newspapers while we focus on

three leading newspapers t hat are tailo r ed to national economic and financial news. Second,

our keyword search features a more refined focus on monetary policy in the U.S., while Baker,

Bloom, and Davis (2016) include a considerably broader set of words in a string of “or”s that

potentially include discussions of other central banks or Fed chairman, for example, “Bernanke”,

“Volker”, “Greenspan”, “central bank”, “Fed chairman”, “Fed chair”, “European Central Bank”,

“ECB”, “Bank of England” , “Bank of Japan”, “BO J” , “Bank of China”, “Bundesbank”, “Bank

of France”, “Bank of Italy”. Third, they scale the total number of identified articles by the

22

See Husted, Rogers, and Sun (2016a).

16

total number of articles rather than the number mentioning “Federal Reserve” (broadly). In

order to understand the importance of these different index construction strategies, we conduct

a “reconciliation analysis” in Appendix D. We conclude from our reconciliation analysis that in

order of importance, the factors explaining the weak correlation between MPU-HRS and MPU-

BBD can be ranked: (1) Newspapers, (2) Keywords, and (3) Scaling. Given their significantly

larger set of search terms and newspapers, it is likely that theirs captures a relatively larger

global factor while ours is more U.S. centric.

23

5.2 Movements in MPU around central bank meeting days

To further understanding of our MPU index, we examine how it evolves on the days before and

after po licy meeting days. It is natural to expect that monetary policy uncertainty would decline

after t he FOMC meets, assuming that policy (in)actions and the associated explanations help

mitigate near-term uncertainty about monetary policy. Furt hermore, it is logical that enhanced

FOMC communication policies will affect uncertainty. These considerations lead us to examine

the level of monetar y policy uncertainty a round FOMC meetings in two sub-periods: February

1994-November 2008 and December 2008 -January 2016.

24

The results are depicted in Figure 12. In both sub-periods, there is a rise in MPU in the days

prior to FOMC meetings. In the earlier sub-period, MPU peaks on the day after the FOMC

meeting, the first day of newspaper coverage. Comparing the two lines, we see that in the

latter sub-period, when the FOMC bega n to rely increasingly on f orward guidance, this rise in

MPU is greatly muted and uncertainty peaks one day sooner.

25

Checking articles’ time-stamping

indicates t hat this finding is not a mechanical result of earlier on-line availability of news in the

latter sub-period. The evidence is thus consistent with the notion that enhanced communications

policies helped ease uncertainty regarding monetary policy by building in expectations of both

the near-term and lo nger-term course of mo netar y policy.

23

We also repeat the VAR analysis for these alter native measures of monetary policy uncertainty and repor t

similar results in Appe ndix F.

24

It is natural to believe that newspaper coverage of moneta ry policy also rises in the days proceeding FOMC

meetings and declines afterward. Hence the importance of our dividing the raw count of identified articles by the

number mentioning “Federal Reserve”.

25

Our MPU index rises on the day after the FOMC meetings in the Fe bruary 1994- November 2008 sample:

Fro m human reading of these article s, we note that news articles on the day after the meetings often discus s (1)

uncertainties in economic consequences of the Fed decision and/or (2) uncertainties in near-term/future monetary

policy actions although curr ent uncertainty seems to have abated.

17

5.3 Does FOMC Communication Influ enc e MPU?

Commentato r s on central banking have long emphasized factors such as transparency and cred-

ibility. Concerning the current communication regime at the Fed, Bernanke (2015) recently

opined: “I hope that t he Fed’s increased tra nsparency will help it maintain its independence,

even as it remains democrat ically accountable. The chair’s press conferences, the expanded eco-

nomic and interest rate projections by FOMC participants, and the lively debate evident in Fed

policymakers’ speeches continue to provide the Congress, the public, and the markets with con-

siderable infor ma t ion about the Fed’s strategy and its rationale. The days of secretive central

banking are long gone. The Federal Reserve is not o nly one of the world’s most transparent

central banks, it is also one of the most transparent government agencies in Washington.”

Indeed, it wasn’t always this way. Goodfriend (1986) notes that the Federal Reserve for-

merly held a strong penchant for secrecy. In an influential theoretical paper, Cukierman and

Meltzer (1986) examine the implications of a central bank’s informational advantage for policy-

maker credibility and inflation. They establish conditio ns under which ambiguity and imp erfect

credibility are preferable from the po int of view of the po licymaker to explicit fo rmulation of

objectives and perfect credibility. In an extension, Faust and Svensson (1999, 2001) study cen-

tral bank transparency, credibility, and reputation. They derive the endogenously determined

degree of tr ansparency, show that a n equilibrium with low transparency is a likely outcome of

the model, and assert that it is (wa s) appropriate to char acterize the Federal Reserve and Bun-

desbank in that way. However, the 1990s elicited fresh analysis from central banking theory, and

wa s accompanied by a sea change of monetary policy making across the globe (Inflation Reports,

inflation targ eting) . Woodf ord (2013) and Bianchi and Melosi (2017) both find advantages for a

central bank that communicates explicitly about its future policy.

26

In Table 2 , we characterize the relationship between our index of monetary policy uncertainty

and variables that proxy for the considerations noted above. These variables ar e discussed in

detail in Appendix E. We focus on institutional or procedural features, including dissenting

vo t es, member turnover, and newly-constructed measures of “FOMC statement persistence” and

26

Milton Friedman (1990) is perhaps most blunt about the FOMC and the long gone days referred to by

Bernanke: “From revealed preference, I suspect that by far and away the two most important var iables in their

loss functions are avoiding accountability on the one hand and achieving public pr e stige on the other”. More

recently, in “The Fed’s Communication Breakdown,” Project Syndicate, November 13, 2015, Ken Rogoff echoe s

Faust-Svensson’s theoretical finding, remarking, “however good its intentions, the net effect of too much Fed

speak has been vagueness and uncertainty.”

18

“FOMC-revealed uncertainty” ( displayed in Appendix E). We also include a dummy va riable

for the crisis period of 2008H2 , as well as separate dummies for the t erms of different FOMC

Chairs. To allay concerns about endogeneity, we also control for U.S. macroeconomic uncertainty

(Jurado, Ludvigson, and Ng (2015)), financial uncertainty (Ludvigson, Ma, and Ng (2016), and

global geopolitical risk (Caldara and Iacoviello (2017)).

We estimate regressions of the form

MP U

t

= α + βX

t−1

+ γZ

t

+ u

t

,

where X

t−1

includes the prior-meeting values of the institutional variables noted above: dissenting

vo t es, statement persistence, member turnover, and FOMC-revealed uncertainty. Similarly, Z

t

represents current-period values of the contro l variables: macroeconomic uncertainty, financial

uncertainty, and geopolitical risk. We also include separate dummies for each Fed chairperson.

We pay close attention to the timing, e.g., associating dissenting votes at the current meeting

with MPU over the following inter-meeting period.

27

As seen in Table 2, the regression coefficients are mostly of the anticipated sign. Sta t ement

Persistence is negative and significant: greater similarity in the language used by the FOMC

in its St atement from meeting t o meeting is followed by lower MPU. We also find that greater

financial uncertainty and geopolitical risk are robustly followed by higher MPU.

This analysis indicates that there is some significant effect of FOMC communications on

MPU. However, at a deeper level the conceptual underpinning of our MPU index is potentially

quite encompassing. Consider the increased importance of forward guidance, especially as interest

rates hit the effective lower bound. Gurkaynak, Sack, and Swanson (2 005) show that much of the

surprise news about monetary policy at the time of FOMC announcements arises from signals

about the central bank’s intentions about future monetary policy. Far future forward guidance

has also been shown to be extremely powerful ( e.g. Eggertsson and Woodford (20 03), Carlstrom,

Fuerst, and Paustian (2012) , D el Negro, Giannoni, and Patterson (2013)): promises abo ut far

future interest rates have huge effects on current economic outcomes, and these effects gr ow with

the ho rizon of the f orward g uida nce. However, uncertainty also grows with the horizon of central

bank promises, given limited cent ral bank credibility and imperfect communication strategies.

Episodes of financial turmoil, for example, around the Taper Tantrum of 2013 and prior to the

27

We also tried several other controls, e.g., natural dis aster and Ramey fisca l policy shocks, but found them to

be insignificant. Appendix E describes all of the va riables used in this analysis.

19

October 2015 FOMC meeting, make apparent that a great deal o f uncertainty exists regarding

the timing of liftoff, which has a strong economic effect. Our MPU index is able to capture this

important element of uncertainty regarding monetary policy, namely, t he timing and path of

future interest rates. As we saw above, MPU shocks have strong contractionary effects on real

and financial variables in the aggregate.

There is a lso a theoretical literature examining the effects of uncertainty o n central bank

communication and policy rules. An earlier part of the literature modeled uncertainty about the

interest rate rule. Rudebusch (2001, 2002) considers uncertainty about the parameters in the

central bank’s policy rule, as well as real-time data uncertainty. Ehrmann-Smets (2003) examine

implications of optimal monetary p olicy when the central bank follows a Taylor Rule but there

is uncertainty about potential output. One result that emerges is that it is optimal to appoint a

more “hawkish” central bank. Levin-Wieland-Williams (2003) consider optimal monetary policy

when the central bank has model uncertainty, i.e., it does not know the “true” model of the

economy a nd so considers several alternat ives. They identify the key characteristics of policy rules

that are robust to such uncertainty. In Eusepi-Preston ( 2010), agents have uncertainty about

the interest rate path that the central bank will follow, while the centr al bank has uncertainty

about the economic state. They show that, absent communication, t he Taylor principle is not

sufficient for macroeconomic stability, and analyze several different communication strategies for

the central bank to follow. More recently, Bianchi-Melosi (2016, 20 17) model monetary policy

under the assumption that agents have uncertainty about whether the central bank is fo llowing

“passive” or “active” inflation stabilization.

5.4 Power of Forward Guidance under Uncertainty

Taking a cue from the literature above, in this section we provide a concrete example of what,

conceptually, our MPU captures and its pot ential effects on the real economy. We extend McKay,

Nakamura, and Steinsson (2016) (hereafter, MNS) to allow for uncertainty in forward guidance.

These authors use a model with uninsurable idiosyncratic shocks to household productivity,

borrowing constraints, and nominal rigidities, to analyze the economic effects of forward guidance.

We incorporate into their framework uncertainty about whether the Fed would change the rate

as promised.

Standard monetary models imply that far future forward guidance has large effects on current

20

outcomes, and that these effects grow with the horizon of the forward guidance. MNS show that

in a model with incomplete ma r kets, forward guidance has substantially less power to stimula te

the economy, because a precautionary savings effect tempers households’ responses to changes

in future int erest rates. In their model, there is some probability that one will face a borrowing

constraint before the pr omised future interest rate reduction, effectively shortening one’s planning

horizon. Also, ho useholds that are subject to uninsurable idiosyncratic income risk and borrowing

constraints will be reluctant to run down their wealth since this will reduce their ability to smooth

consumption in the face of future income shocks.

The MNS economy is populated by a unit continuum of ex ant e identical households with

preferences given by

E

0

∞

X

t=0

β

t

C

1−γ

ht

1 − γ

−

l

1+ψ

ht

1 + ψ

,

where C

h,t

is consumption of household h at time t and l

h,t

is la bor supply of household h at time

t. Households are endowed with stochastic idiosyncratic productivity z

h,t

that generates pretax

labor income W

t

z

h,t

l

h,t

, where W

t

is the aggr egate real wage. Each household’s productivity z

h,t

follows a Markov chain with tra nsition probabilities P r(z

h,t+1

|z

h,t

). The initial cross-sectional

distribution of idiosyncratic productivities is equal to the ergodic distribution of this Markov

cha in, denoted by τ(Z

it

).

A final good is produced from intermediate inputs according to Y

t

=

R

1

0

y

t

(j)

1/µ

dj

µ

, where

Y

t

denotes t he quantity of the final good produced at time t and y

j,t

denotes the quantity of the

intermediate good pro duced by fir m j in period t. The intermediate goods are produced using

labor as an input according to the production function y

t

(j) = n

t

(j), where n

j,t

denotes the

amount of labor hired by firm j in period t.

While the final good is produced by a representative competitive firm, the intermediate goods

are produced by monopolistically competitive firms. The intermediate g oods firms face frictions

in adjusting their prices and can only update their prices with probability θ per period. These

firms are controlled by a risk-neutral manager who discounts future profit s at rate β. Whatever

profits a re produced are paid out immediately to the households with each household receiving

an equal share D

t

. Households cannot trade their stakes in the firms.

Households trade a risk-free real bond with real interest rate r

t

between periods t and t + 1.

Borrowing constraints prevent these households from taking negative bond positions. There

is a stock o f g overnment debt outstanding with real face value B. The government raises tax

21

revenue to finance interest payments on this debt. These taxes ar e collected by taxing households

according t o their labor productivity z

h,t

. The tax paid by a household h in period t is τ

t

¯τ(Z

it

).

The government r uns a balanced budget so as to maintain a stable level of debt in each period.

MNS analyze an experiment in which the monetary authority announces that the real interest

rate will be lowered by 1 percent for a single quarter five years in the future. The real rate is

maintained in all other quarters. Using the MNS calibration, we run a thought experiment to

analyze the effects of uncertainty households may perceive a bout forward guidance: we assume

that households believe that there is a 50% chance that the central bank will follow through on

the rate decrease five years in the future and a 50% chance that there is no rate change in five

years.

Figure 13 plots the response of output to this shock in our extended MNS model, as well as in

the complete and incomplete mar kets versions of the MNS model. The response of output under

complete markets is a step function: Output immediately jumps up and remains at that elevated

level for 20 quarters before returning to steady state. Consistent with MNS, output has a smaller

initial response and is substantially smaller in the incomplete markets model than under complete

markets, even in the period right before the interest rate decrease. This is because households

trade off the cost of a lower buffer stock (more exposure to future income shocks) with the gains

from intertemporal substitution, since they are no longer fully insured against all shocks as they

wo uld be with complete markets. In our experiment, when there is uncertainty about whether

the rate decline promised under forward guidance will actually materialize, households discount

the promise. This results in a muted effect of forward guidance, both at the outset and for the

response in the period before quarter 2 0. In addition, ho useholds’ risk aversion implies that ,

by Jensen’s inequality, uncertainty abo ut future interest ra t es further depresses the stimulating

effects of the a nno uncement.

28

Thus, consistent with our empirical findings, a theoretical argument can be made that forward

guidance has less power to stimulate the economy when households perceive some uncertainty

about whether the promised rate cut will mat erialize.

28

This effect is quantitatively small under the MNS calibration. This second-order Jense n’s inequality effect

(that further reduces o utput) is counteracted by a smaller redistribution effect: the interest rate shock leads to a

redistribution of wealth away from hous eholds with high marginal propensities to consume and toward households

with low margina l propensities to consume, which lowers aggregate demand and output; this effect is s ignificantly

smaller with our assumption in our ex periment.

22

6 Conclusion

We develop new measures of monetary policy uncertainty: uncertainty tha t the public perceives

about Federal Reserve policy actions and their consequences. We compare t hese new measures to

existing proxies and argue tha t there are good reasons to prefer ours, especially over medium term

horizons such as FOMC meeting intervals. Empirically, we note for example that market-based

measures were well subdued–close to zero–during the ZLB while ours were elevated and fluctu-

ating. Conceptually, differences exist between our measure and the market-based indicators. In

theory, the latter reflect the average perception of individuals participating in options markets.

Our news-based index reflects the average opinion of people reading newspapers (assuming that

newspapers reflect the readership). Since relatively few households participate in the optio ns

markets, the prices in these markets may not be particularly representative. In a ddition, in

market-based indicators the perceived degree of uncertainty is contaminated with time-varying

risk aversion and state-dependent marginal utility.

29

Although we acknowledge (and try to con-

trol for) the potential state-dependency in newspaper coverage of centra l bank actions, we believe

that our index is a preferable measure of monetary policy uncertainty, at least over the sample

period and for the frequency we study.

We examine transmission of monetary policy uncertainty, showing that greater uncertainty

has contractionary effects. Positive shocks to monetary policy uncertainty raise credit costs and

lower output with about the same dynamic pattern as do identified contractionary monetary

policy shocks such as GK’s that are regarded as standard in the literature. The mag nit ude

of estimated effects is at least as large as, if not larger than, those of monetary policy shocks.

These results are robust to alternative measures of monetary policy uncertainty (Appendix F).

Consistent with this, we make a simple theoretical argument why forward guidance could be less

stimulative when households perceive some uncertainty about whether promised rate cuts will

materialize.

Our findings are in line with others in the literature that illustrate nega t ive economic ef-

fects of uncertainty shocks. Our analysis suggests that if p olicy rate normalization is successful

in alleviating the public’s uncertainty regarding monetary policy, that can help neutralize the

29

The market-based measure s are presumed to reflect the price individuals are willing to pay for insurance

against future policy rate fluctuations. Willingness to substitute resources from one possible future to another

depe nds on the rela tive scarcity of resources in those futures. Therefore, a household may be willing to pay a lot

to insure against the possibility of a rate increase even if the household sees the outcome as highly unlikely.

23

contractionary effects of the rat e increases themselves.

References

[1] Acosta, Miguel 2015. “FOMC Responses t o Calls for Transparency,” Finance and Economics

Discussion Series 2015-060, Boa rd of G overnors of the Federal Reserve System.

[2] Akkaya, Yildiz, Refet S. Gurkaynak, Burcin Kisacikoglu, and Jonathan H. Wright 2015.

“Forward Guidance and Asset Prices,” working paper, Johns Hopkins University.

[3] Angrist, Joshua D., and Alan B. Krueger. 2001. “Instrumental Varia bles and the Search f or

Identification: From Supply and Demand to Natural Experiments.” Journal of Economic

Perspectives, 15(4): 69-85.

[4] Azzimonti, M. 2017. “Partisan Confict and Private Investment,” Jo urnal of Monetary Eco-

nomics, Forthcoming.

[5] Ba chmann, R., S. Elstner, and E. Sims 2013. “Uncertainty and Economic Activity: Evidence

from Business Survey Data,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 5(2), 217-249.

[6] Ba chmann, R., and G. Moscarini 2012. “Business Cycles and Endogenous Uncertainty,” Yale

University working paper.

[7] Ba ker, Scott, Nicholas Bloom, a nd Steven J. Davis, 2016. “Measuring Economic Policy Un-

certainty,” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 131, 1593-1636.

[8] Ba uer, M. D., 20 12. “Monetary Policy and Interest Ra t e Uncertainty,” Federal Reserve Board

San Francisco Economic Letter 2012-38.

[9] Bernanke, Ben S, 201 5. The Courage to Act: A Memoir of a Crisis and its Aftermath. W.W.

Norton and Company, New York.

[10] Bianchi, F., Melosi, L. 2016. “Modeling the Evolution of Expectations and Uncertainty in

General Equilibrium,” International Economic Review, 57(2), 717-756.

[11] Bianchi, Francesco, and Leonardo Melosi, 2017. “Constrained Discretion and Central Bank

Tr ansparency,” Review of Economics and Statistics, forthcoming.

[12] Bloom, N. 2009 . “The Impact of Uncertainty Shocks,” Econometrica, 77(3), 623-685.

[13] Boukus, Ellyn, and Rosenberg, Joshua. 2006. “The inf ormation content of FOMC minutes,”

Federal Reserve Ba nk of New York.

[14] Brainard, Lael, 2017. “Monetary Policy in a Time of Uncertainty,” Brookings Institution,

Washington, D.C. January 17, 2017.

[15] Caldara, Dario, and Matteo Iacoviello (2017), “Measuring Geopolitical Risk,” unpublished

paper, Board of the Governor s of the Federal Reserve Board, September 2016, available at

https://www2.bc.edu/matteoiacoviello/gpr

files/GPR PAPER.pdf

[16] Campbell, J.R., C.L. Evans, J.D. Fisher, and A. Justiniano, 2012. “Macroeconomic Effects

of Federal Reserve Fo r ward Guidance,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring, pp.

1-54.

24

[17] Campbell, J.R., J.D. Fisher, A. Justiniano, and L. Melosi, 2016. “Forward Guidance and

Macroeconomic Outcomes since the Financial Crisis,” Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, WP

2016-07.

[18] Carlson, J. B., Craig, B. R., and Melick, W. R., 2005. “Recovering Market Expectations of

FOMC Rate Changes with O ptions o n Federal Funds Futures,” Journal of Futures Markets,

25, 1203-1242.

[19] Carlston, Benjamin, and Marcelo Ochoa, 2016. “Macroeconomic Announcements and In-

vestors Beliefs at the Zero Lower Bound,” working paper, Federal Reserve Board.

[20] Creal, Drew D., and Jing C. Wu, 2016. “Monetary Policy Uncertainty and Economic Fluc-

tuations,” International Economic Review, forthcoming.

[21] Cukierman, Alex, and Allan H. Meltzer. 1986. “A Theory of Ambiguity, Credibility, and

Inflation under Discretion and Asymmetric Information,” Econometrica 54, 1099-11 28.

[22] Davis, A. K., J. Piger, and L. M. Sedor. 2012. “Beyond The Numbers: An Analysis Of

Optimistic And Pessimistic Language In Ear nings Press Releases,” Contemp orary Accounting

Research, 29, 845 868.

[23] Demers, E., and C. Vega , 20 10. “Soft Informa t ion In Earnings Announcements: News Or

Noise?” Working Paper, INSEAD.

[24] Ehrmann, M., Smets, F. 2003. “Uncertain Potentia l Output: Implications for Monetary

Po licy,” Journa l of Economic Dynamics and Control, 27 ( 9), 16 11-1638.

[25] Ehrmann, Michael, and Fratzscher, Marcel. 2007. “Communication by central bank commit-

tee members: different strategies, same effectiveness?” Jour nal of Money, Credit and Banking,

39(2-3), 509541.

[26] Emmons, W. R., Lakdawala, A. K., and Neely, C. J., 2006. “What Are the Odds? Option-

Based Forecasts of FOMC Target Changes,” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review,

November/December 2006, 88, 543-61.

[27] Engen, Eric M., Thomas T. Laubach, and David Reifschneider. 2015. “The Macroeconomic

Effects of the Federal Reserve’s Unconventional Monetary Policies,” Finance and Economic

Discussion Series 2015-005. Boa rd of G overnors of the Federal Reserve System.

[28] Engelberg, J. E. , 2008. “Costly Information Processing: Evidence From Earnings An-

nouncements,” Working Paper, University of North Carolina.

[29] Eusepi, S., Preston, B. 2010 . “Central Bank Communication and Expectations Stabiliza-

tion,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 2 ( 3), 23 5-271.

[30] Faust, J., and L. E. O. Svensson. 1999. “The Equilibrium Degree of Transparency and

Cont r ol in Monetary Policy,” Journa l of Money, Credit, and Ba nking.

[31] Faust, J., and L. E. O. Svensson. 2001. “Transparency and Credibility: Monetary Policy

with Unobservable Goals,” International Economic Review, 42(2).

[32] Feldman, R., S. Govindaraj, J. Livnat, and B. Segal, 20 10. “Managements Tone Change,

Po st Earnings Announcement Drift And Accruals,” Review of Accounting Studies 15 , 915953.

25

[33] Fernandez-Villaverde, J., P. Guerron-Quintana, K. K uester, and J. Rubio-Ramirez 2015.

“Fiscal Volatility Shocks and Economic Activity,” forthcoming in American Economic Re-

view.

[34] Fernandez-Villaverde, J., P. Guerron-Quintana, J. F. Rubio-Ramirez, and M. Uribe 2011.

“Risk Matters: The R eal Effects of Vola t ility Shocks,” American Economic Review, 101(6),

2530-61.

[35] Fischer, S. 2017. “Monetary Policy Expectations and Surprises”, Columbia University,

https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/fischer20170417a.htm

[36] Goodfriend, Marvin. 1986, “ Monetar y Mystique: Secrecy and Central Banking,” Journal of

Monetary Economics, 17, 63-92.

[37] Hoberg, Gerard, and Gordon Phillips. 2010. “Product Market Synergies and Competition

in Mergers and Acquisitions: A Text-Based Analysis,” Review of Fina ncial Studies 23(10):

37733811.

[38] Husted, L., J. Rogers, and B. Sun, 2016a. “Measuring Monetary Policy Uncertainty: The

Federal Reserve January 1986 t o January 2016,” Federal Reserve Board,

https://www.federalreserve.gov/econresdata/notes/ifdp-notes/2 016/measuring-monetary-

policy-uncertainty-the-federal-reserve-january-1985-january-2016-20160411.html

[39] Husted, L., J. Rogers, and B. Sun, 2016b. “Measuring Cross-Countr y Monetary Policy Un-

certainty,” Federal Reserve Board, https://www.federalreserve.gov/econresdata/notes/ifdp-

notes/2016/measuring-cross-country-monetary-policy-uncertainty-20161123.html

[40] Jurado, Kyle, Sydney C. Ludvigson a nd Serena Ng. 2015. “Measuring Uncertainty.” Amer-

ican Economic Review, 105(3): 1177-1216.