THE EFFECTS OF INCOME ON THE ECONOMIC WELLBEING OF FAMILIES

WITH LOW INCOMES: EVIDENCE FROM THE 2021 EXPANDED CHILD TAX

CREDIT

By Natasha Pilkauskas, Katherine Michelmore, and H. Luke Shaefer

KEY FINDINGS

• Across six months in 2021, families reported using the monthly

Child Tax Credit (CTC) on bills, other household expenses, and

child-related expenses.

• We find robust evidence that the CTC reduced the overall num-

ber of material hardships experienced by families, particularly

food insecurity.

• Other evidence suggests that the monthly CTC reduced medical

hardships, inability to pay utility bills, and reliance on friends

and family for food.

• We do not find a statistically significant relationship between the

employment behaviors of families in our study and the monthly

CTC benefit.

INTRODUCTION

Interest in basic income and unconditional cash transfers as a

means of improving well-being has grown substantially over the last

few years in the United States. There remains much to learn about

the causal effects of unconditional cash transfers despite a large

evidence base suggesting that income

1, 2, 3

, in-kind policies

4, 5, 6

, and

earnings supplements

7, 8, 9

improve well-being.

New evidence from randomized control trial studies of unconditional

cash transfers find modest to null effects on material well-being

10,

11, 12, 13

, raising further questions about the causal link between cash

transfers and material well-being. In contrast, a small but growing

set of studies of a universal, recurring monthly unconditional cash

transfer to families with children – the 2021 monthly Child Tax

Credit (CTC) – suggests this policy improved the material well-being

of families with children

14, 15, 16

.

In this brief, we add to this growing literature by summarizing

the findings of a new study of the 2021 monthly Child Tax Credit.

Unlike earlier research, our study focuses on families with very

low incomes, those living in poverty. Using quasi-experimental

techniques, we find robust evidence that the 2021 monthly CTC

improved families’ material well-being and had little to no impact on

their employment.

THE 2021 CHILD TAX CREDIT

In March 2021, Congress passed the American Rescue Plan Act,

temporarily expanding the Child Tax Credit. This temporary

expansion increased the size of the benefit (including a larger benefit

for children under age 6), extended eligibility to households with

little or no earnings, and made the credit fully refundable. Finally,

half of the credit was disbursed monthly for the final six months of

2021, while the remaining balance was delivered as a lump sum at

tax time in early 2022. Removing the earnings minimum and making

the credit fully refundable made 26 million children eligible for a

larger credit — 6 million of whom were entirely ineligible before the

reform because their families’ earnings were too low

17

. Our study

focuses on these children, those at the lowest end of the income

distribution and who have historically been excluded from the full

benefits of the CTC.

THE DATA AND APPROACH

Poverty Solutions partnered with Propel, creators of the Providers

app, which helps more than 5 million families manage their

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits,

encompassing about one-quarter of all SNAP users. Every month,

Propel invites a random national sample of its users to take an

online survey on a variety of topics related to household financial

well-being, including a number of questions related to the expanded

CTC. Roughly 4,000-6,000 users respond to the survey each month

from all 50 states, about half of whom live in households with

children under the age of 18 — the focus of our study. We use data

from surveys conducted between June 2021 and January 2022 to

study the effects of the 2021 monthly CTC on the economic well-

being of families with children.

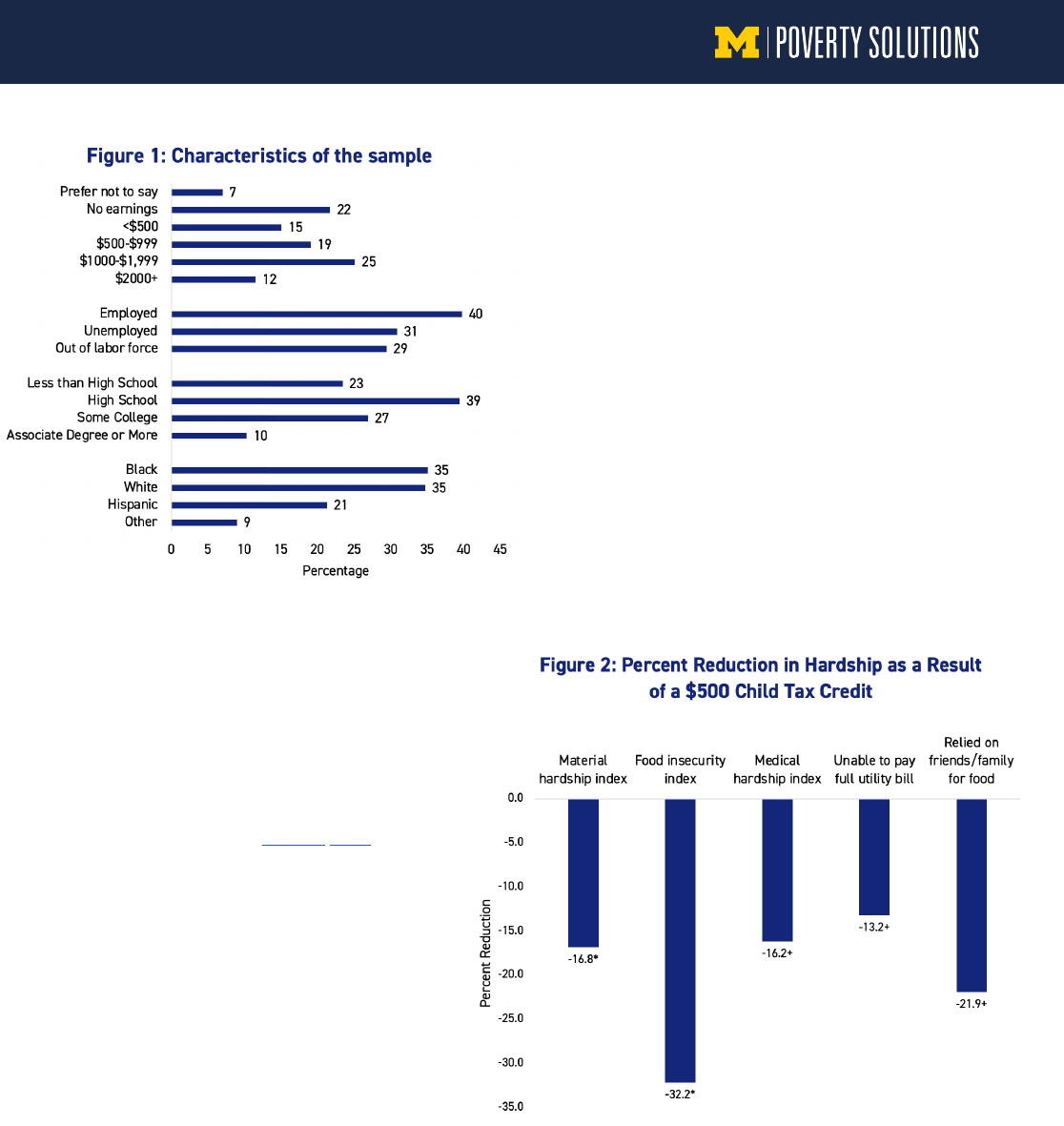

Figure 1 provides information on the characteristics of parents in

our study sample. Monthly earnings of families are very low: 22%

reported having no household earnings and another 15% had less

than $500 in monthly earnings. Additionally almost one-third of

parents were unemployed and another 29% were out of the labor

force. Sixty-two percent of parents in our study have a high school

degree or less. The sample is racially diverse: 35% of parents are

Black, 35% are White, 21% are Hispanic and 9% report an “other”

race/ethnicity.

September 2022

1

We compare families before and after the implementation of the

credit, using differences in the number and ages of children to

estimate the impacts of the monthly credit on families with

low incomes. In this brief, we present our estimates of the

impacts of the expanded CTC based on our most conservative

statistical modeling approach

18

. We have the most confidence

in our findings that are substantively similar and statistically

significant across our statistical modeling approaches. We

refer to these as “robust.” When the results are similar but not

significant across all models, we say they are “suggestive.”

As we have documented in previous research briefs

19, 20

, many

families did not receive the monthly CTC (only 66% in this

sample). Here we estimate the impact of the CTC for those who

did receive the CTC

21

. For more detail on our methodological

approach, see our full working paper.

HOW DO FAMILIES REPORT SPENDING THE 2021

MONTHLY CTC?

We first present findings from an open-ended question that

asked respondents who received the 2021 monthly CTC how

they spent their credit. The results, in Table 1, indicate families

spent the money in ways that should improve their material

well-being and reduce hardships. The vast majority of families

(about 75%) reported using the money to “pay bills” in

every survey month. Families also used the money for

other basic necessities such as paying rent (9%) and

buying food (8%). Many parents used the money on child-

related expenses, buying school supplies (especially in

the late summer months) and children’s clothing. Thus, based on

these responses, we expect to find that the credit reduced material

hardships as well.

DID THE EXPANDED CTC IMPROVE ECONOMIC WELL

BEING?

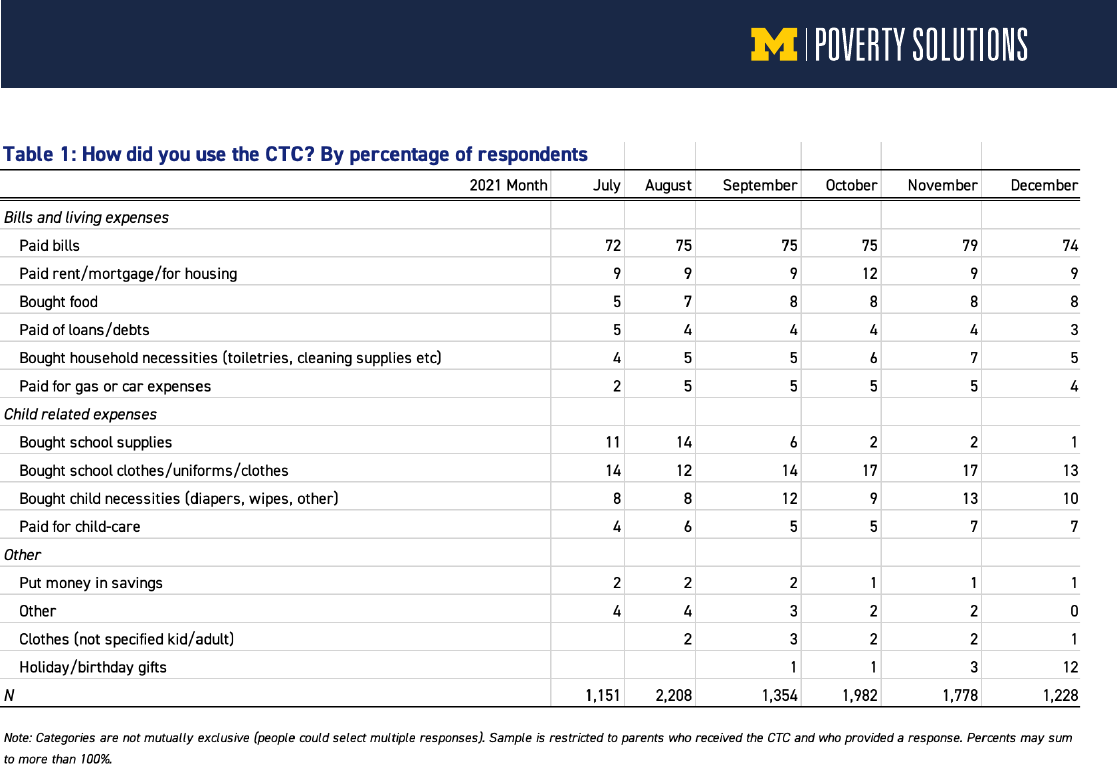

In Figure 2, we show the results from our statistical model of the

effects of the 2021 monthly Child Tax Credit on material hardship

outcomes. We present the percent reduction in each outcome

based on a $500 monthly CTC, the average CTC amount received by

families in our study.

We find robust evidence that the CTC reduced the overall number

of material hardships experienced by families and children with low

incomes. Our statistical model indicates that a $500 monthly CTC

reduced the number of hardships experienced by families by nearly

17%. Similarly, we find robust evidence that the CTC cut reports of

food insecurity by almost one-third.

The evidence for reductions in medical hardships, being unable

to pay a full utility bill, and relying on friends and family for food

is somewhat less certain. Although the CTC appears to have

reduced the incidence of these hardships, these point estimates

were statistically significant in some models, but not all. Thus, we

interpret these findings as suggestive.

Note: * indicates findings are statistically significant and robust across models. + indicates

findings do not reach conventical levels of statistical significance in our most stringent test;

however, they are negatively signed and similar in size to the estimates with household size

fixed-effects, which do reach conventional levels of statistical significance. Thus we consider

these results as suggestive evidence. See the full paper for details on modeling approaches.

2

3

In addition to the material hardships shown in Figure 2, we also

examined the effects of the CTC on a number of additional hardship

and economic well-being measures and found no effects of the CTC

on these outcomes. We found no effect of the CTC on:

• Severe housing hardship (like eviction and homelessness)

• Whether families decided not to pay a bill

• Families’ ability to get to appointments, work, or somewhere else

• Whether families reported having “everything they typically need”

• The total money families had on hand

• The time that the money they had on hand would last

• Whether they borrowed money from friends and family

• Whether they visited a food pantry in the last month

It is perhaps surprising that we find no effects on these indicators

of material well-being. For some outcomes, like severe housing

hardship, it may be the case that the monthly benefit was not

sufficient to address this hardship. Many families in our study are

also in debt; thus, because the credit was relatively short-lived,

families may not have been able to get fully out of debt and back on

their feet with the six-month credit. It might also be surprising that

we find no impact of the monthly 2021 CTC on the total money that

families had on hand, but this could be explained by the fact that our

survey was conducted between two and four weeks after each of the

monthly payments was disbursed. Given the very low incomes of our

respondents and the fact that very few report saving their credit, it

is possible that most families had already spent down their credits

by the time of the survey.

DID THE 2021 MONTHLY CTC AFFECT EMPLOYMENT?

Policymakers and politicians have been concerned the 2021 monthly

CTC might reduce employment. Several studies have found no

effects of the CTC on employment

22, 23, 24, 25

and the results from our

study affirm those findings.

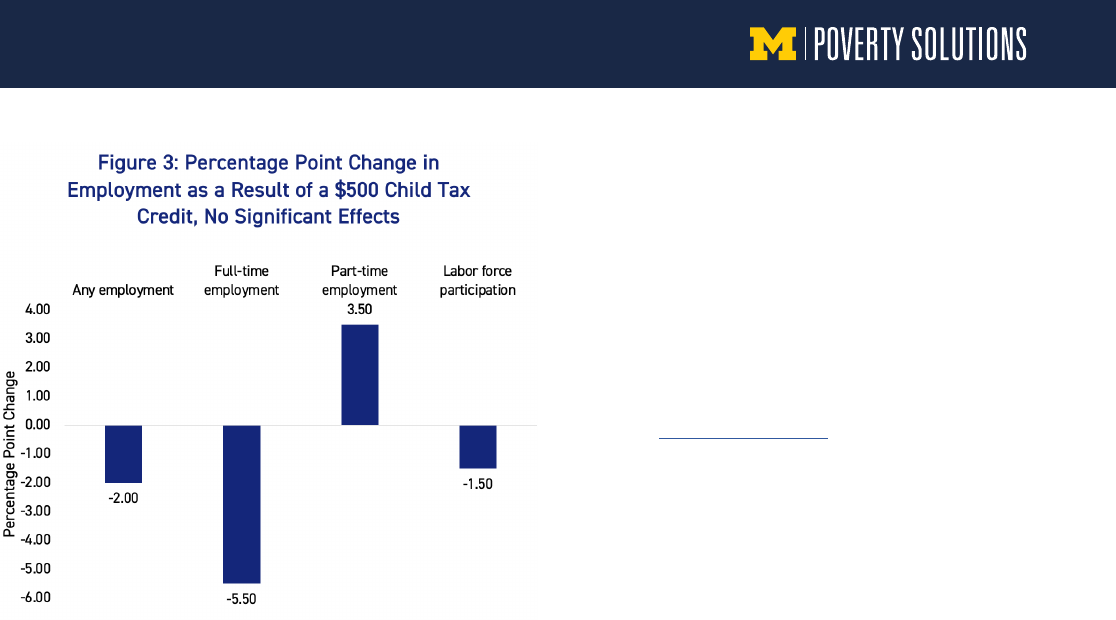

In Figure 3, we show the percentage point change in employment

because of a $500 monthly CTC. Here, unlike Figure 2, we show

percentage point change for consistency with other studies

26

and

none of the estimates shown here are statistically significant. The

point estimates suggest a possible shift from full-time employment

to part-time employment, but these findings are not robust across

model specifications. Thus, we conclude the 2021 CTC had little to no

effect on the employment of families with very low incomes.

DID THE EFFECTS OF 2021 MONTHLY CTC DIFFER BY

INCOME AND RACE/ETHNICITY?

We examined differences in the effects of the 2021 CTC by income,

comparing those with extremely low incomes (below $500 in

monthly earnings) to those with low incomes ($500 or greater in

monthly earnings). We did this because those at the very bottom are

very unlikely to have received the CTC in the past and because there

is evidence from other studies that cash transfers that represent

a larger proportion of household income have bigger effects

27, 28, 29

.

However, we find little to no evidence of differences in the effects by

household income.

Note: We find no statistically significant effects of the monthly CTC on any labor

supply or employment outcomes.

We also studied differences in the effects of the CTC by race/

ethnicity as research suggests there are important intersections

between tax policy and racial inequality

30

. As a result of making

the credit fully refundable and removing the earnings minimum,

Hispanic and Black families were more likely to become newly

eligible or fully eligible for the CTC with the 2021 expansion

31,

32

. Thus, the 2021 CTC provided these families with new support

relative to White families, who have historically had higher eligibility

rates. We find some evidence that the 2021 CTC helped reduce

hardships among Black families more than White or Hispanic

families, but the differences were not large.

CONCLUSION

Our study focuses on a sample of families with very low incomes,

who were most likely to gain access to the CTC in 2021. We find that

families spent their monthly CTC on bills and expenses that should

improve their material well-being. We also find that the monthly

CTC reduced families’ overall number of material hardships and, in

particular, their food insecurity. These findings are in keeping with

other studies of the effects of the CTC on broader populations

33,

34

. Similarly, we find no evidence of an effect of the CTC on the

employment of families with low incomes, consistent with evidence

from other studies

35

. We also find suggestive evidence that the CTC

improved other measures of material well-being (reduced medical

hardships, inability to pay utility bills, and reliance on friends and

family for food).

The 2021 monthly CTC was short-lived. Thus, it is hard to know

what the effects of a longer-term, more stable credit would be.

Nonetheless, our research suggests the credit reduced material

hardship for families with very low incomes, which prior research

suggests should improve child and family well-being

36, 37

.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Natasha Pilkauskas and Katherine Michelmore are associate

professors of public policy at the Gerald R. Ford School of Public

Policy at the University of Michigan. H. Luke Shaefer is the faculty

director of Poverty Solutions, the Hermann and Amalie Kohn

Professor of Social Justice and Social Policy, and a professor of

public policy and social work at U-M.

The authors would like to acknowledge Propel for its partnership in

fielding the survey and sharing results for analysis. We would also

like to thank U-M Poverty Solutions associate Samiul Jubaed for

his assistance with the data cleaning as well as Nicole Kovski, who

co-authored the paper summarized in this brief. We also thank the

Washington Center for Equitable Growth and the Lynn and Charles

Schusterman Family Foundation for their generous support of our

research.

4

ENDNOTES

1 Duncan, G. J., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (Eds.). (1997). Consequences of growing up poor. Russell Sage Foundation.

2 Akee, R. K., Copeland, W. E., Keeler, G., Angold, A., & Costello, E. J. (2010). Parents’ incomes and children’s outcomes: A quasi-

experiment using transfer payments from casino profits. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 2(1), 86-115.

3 Troller-Renfree, S. V., Costanzo, M. A., Duncan, G. J., Magnuson, K., Gennetian, L. A., Yoshikawa, H., ... & Noble, K. G. (2022). The impact

of a poverty reduction intervention on infant brain activity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(5), e2115649119.

4 Shaefer, H. L., & Gutierrez, I. A. (2013). The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program and material hardships among low-income

households with children. Social Service Review, 87(4), 753-779.

5 McKernan, S. M., Ratcliffe, C., & Braga, B. (2021). The effect of the US safety net on material hardship over two decades. Journal of

Public Economics, 197, 104403.

6 Schmidt, L., Shore-Sheppard, L., & Watson, T. (2016). The effect of safety-net programs on food insecurity. Journal of Human

Resources, 51(3), 589-614.

7 Kondratjeva, O., Roll, S. P., Despard, M., & GrinsteinWeiss, M. (2021). The impact of state earned income tax credit increases on

material and medical hardship. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 55(3), 872-910.

8 Kondratjeva, O., Roll, S. P., Despard, M., & Grinstein-Weiss, M. (2022). The Impact of Tax Refund Delays on the Experience of Hardship

Among Lower-Income Households. Journal of Consumer Policy, 1-42.

9 Pilkauskas, N., & Michelmore, K. (2019). The effect of the earned income tax credit on housing and living arrangements. Demography,

56(4), 1303-1326.

10 Gennetian, L., Duncan, G., Fox, N., Magnuson, K., Halpern-Meekin, S., Noble, K., & Yoshikawa, H. (2022). Unconditional cash and family

investments in infants: Evidence from a large-scale cash transfer experiment in the U.S. NBER Working Paper No. 30379.

11 Jaroszewicz, A., Jachimowicz, J., Hauser, O., & Jamison, J. (2022). How Effective Is (More) Money? Randomizing Unconditional Cash

Transfer Amounts in the US. Randomizing Unconditional Cash Transfer Amounts in the US (July 5, 2022).

12 Jacob, B., Pilkauskas, N., Rhodes, E., Richard, K., & Shaefer, H. L. (2022). The COVID-19 cash transfer study II: The hardship and mental

health impacts of an unconditional cash transfer to low-income individuals. National Tax Journal, 75(3), 000-000.

13 Pilkauskas, N.V., Jacob, B.A., Rhodes, E., Richard, K. and Shaefer, H.L. (2022). The COVID cash transfer study: The impacts of an

unconditional cash transfer on the wellbeing of low-income families. Poverty Solutions Working Paper.

14 Hamilton, L., Roll, S., Despard, M. , Maag, E., Chun, Y., Brugger, L., Grinstein-Weiss, M. (2022). The impacts of the 2021 expanded child

tax credit on family employment, nutrition and financial well-being: Findings from the Social Policy Institute’s Child Tax Credit Panel

Survey. Brookings Global Working Paper #173.

15 Karpman, M., Maag, E., Zuckerman, S. & Wissoker, D. (2022) Child Tax Credit recipients experienced a larger decline in food insecurity

and a similar change in employment as nonrecipients between 2020 and 2021.Tax Policy Center. Urban Institute and Brookings

Institution.

16 Parolin, Z., Ananat, E., Collyer, S., Curran, M, & Wimer, C. (2021). “The Initial Effects of the Expanded Child Tax Credit on Material

Hardship,” Columbia University Center on Poverty and Social Policy, Poverty and Social Policy Working Paper.

17 Goldin, J. and Michelmore, K. (2020). Who Benefits From the Child Tax Credit? (No. w27940). National Bureau of Economic Research.

18 We use a parameterized difference-in-differences model and present estimates from models that include a number of chil-dren fixed

effect. This approach allows us to compare households with the same number of children before and after the ex-pansion; however,

because the CTC is determined by the number of children in the household, it is a very stringent test (only leaving variation in the

household composition in the age of the children). In the paper, we also estimate models including number of household members

fixed effects as household size more generally is both correlated with the CTC and the out-comes but is a slightly less stringent test of

the relationship.

19 Pilkauskas, N.V. & Cooney, P, (2021). Receipt and usage of the Child Tax Credit payments among low-income families.

5

20 Pilkauskas, N.V. & Michelmore, K. (2021) Families with low incomes and the Child Tax Credit: Who is still missing out?

21 These are estimates that instrument for amount of the CTC received by families. They can be considered treatment on the treated or

local average treatment effects.

22 Ananat, E., Glasner, B., Hamilton, C., & Parolin, Z. (2022). Effects of the Expanded Child Tax Credit on Employment Outcomes: Evidence

from Real-World Data from April to December 2021 (No. w29823). National Bureau of Economic Research.

23 Lourie, B., Shanthikumar, D. M., Shevlin, T. J., & Zhu, C. (2021). Effects of the 2021 Expanded Child Tax Credit. Available at SSRN.

24 Hamilton et al., 2022.

25 Karpman et al., 2022.

26 Ananat et al., 2022.

27 Haushofer, J., Chemin, M., Jang, C., & Abraham, J. (2020). Economic and psychological effects of health insurance and cash transfers:

Evidence from a randomized experiment in Kenya. Journal of Development Economics, 144, 102416.

28 Haushofer, J., & Shapiro, J. (2016). The short-term impact of unconditional cash transfers to the poor: experimental evidence from

Kenya. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(4), 1973-2042.

29 Pilkauskas et al., 2022.

30 Brown, D. A. (2021). The whiteness of wealth: How the tax system impoverishes Black Americans--and how we can fix it. Crown

Publishing Group, New York.

31 Goldin and Michelmore, 2021.

32 Collyer, S., Wimer, C., & Harris, D. (2019). ). Left behind: The one-third of children in families who earn too little to get the full Child Tax

Credit. Poverty & Social Policy Brief, 3(6) New York, NY: Columbia University Center on Poverty and Social Policy.

33 Parolin et al., 2021.

34 Hamilton et al., 2022.

35 Ananat, E., Glasner, B., Hamilton, C., & Parolin, Z. (2021). Effects of the Expanded Child Tax Credit on Employment Outcomes: Evidence

from Real-World Data from April to September 2021. Poverty and Social Policy Discussion Paper.

36 Zilanawala, A., & Pilkauskas, N. V. (2012). Material hardship and child socioemotional behaviors: Differences by types of hardship,

timing, and duration. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(4), 814-825.

37 Thomas, M. (2022). Longitudinal patterns of material hardship among US families. Social Indicators Research, 1-30.

6