Table of Contents

Foreword by the Secretary of the Environment 3

Executive Summary 4

Chapter 1: The Big Picture 11

Introduction 11

From the Dirtiest Air to the Cleanest 12

Maryland’s Climate Pathway 12

Investing Now for a Bright Future 13

Transitioning Away from Fossil Fuels 15

What this Plan Is and Is Not 15

Chapter 2: The Policies 16

Economywide 16

Electricity 18

Transportation 26

Buildings 34

Industry 43

Waste 52

Agriculture 58

Forestry and Land Use 60

Chapter 3: Economic and Public Health Impacts 65

Global Economic Benefits 65

State Economic Benefits 65

State Public Health Benefits 66

Chapter 4: Lower Energy Costs and More Jobs 71

Lower and More Predictable Household Energy Costs 71

Technology Development and Deployment 74

Clean Energy Jobs and Workforce Development 75

Chapter 5: Funding the Transition 77

State Investments 77

Green Bank Investments 79

Federal Investments 80

Chapter 6: Implementation 88

Executive Actions 88

Legislative Actions 90

Opportunities for Stakeholder Input in Policy Development 91

CPRG: From Planning to Implementation 92

Progress Tracking and Reporting 95

Appendices 97

2

Foreword by the Secretary of the Environment

As Secretary of the Environment, I am pleased to deliver this

nation-leading plan to meet the most ambitious greenhouse gas

reduction goals of any state.

As outlined in the Climate Solutions Now Act of 2022, the Maryland

Department of the Environment was required to develop a strategy to

reduce greenhouse emissions 60% by 2031 and stay on track to

achieve net zero emissions by 2045. This Administration has not only

accepted that responsibility, but we are holding nothing back in our

effort to fight the climate crisis while leaving no one behind.

The climate crisis is not a far off threat. It’s already here. Maryland’s Climate Pollution Reduction

Plan will counteract the effects of climate change by decreasing the amount of carbon in our

atmosphere. It will also position our state to win the decade by producing jobs, innovation, and

healthier communities.

Implementing this plan will deliver lower energy costs, cleaner air, better transportation options,

new clean industries, green jobs, and a brighter future for Marylanders. But it does not stop here.

While this plan has a strong regulatory foundation, it will take more investment and commitment

from all of us to reach the finish line.

We will meet this moment united and build a better, more sustainable, more resilient, and more

equitable future for everyone. We will show the world that our state can lead in the fight to save

our planet.

Serena McIlwain

Maryland Secretary of the Environment

3

Executive Summary

This is Maryland’s plan to achieve its near-term climate goals and place the state on a path to

achieve net-zero emissions by 2045. New policies will transition the state from the fossil fuel era

of the past to a clean energy future. Marylanders will benefit from cleaner air, improved public

health, lower energy costs, and more jobs with higher wages. As detailed in the plan, new policies

will generate up to $1.2 billion in public health benefits, $2.5 billion in increased personal income,

and a net gain of 27,400 jobs between now and 2031 as compared with current policies. Average

households will save up to $4,000 annually on energy costs. Air quality and public health outcomes

will improve for everyone, especially people living in historically underserved and overburdened

communities.

Maryland has already reduced greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions - also called climate pollution -

faster than almost any other state, achieving a 30% reduction in statewide GHG emissions from

2006 levels by 2020. The Climate Solutions Now Act (CSNA), passed into law in 2022, advances

the most ambitious GHG reduction goals of any state in the nation. The law requires Maryland to

reduce statewide GHG emissions 60% from 2006 levels by 2031 and achieve net-zero emissions

by 2045 but does not outline a dedicated funding source to implement the plan. The Maryland

Department of the Environment (MDE) is responsible for producing the plan to achieve the state’s

GHG reduction goals but achieving the goals will require a whole-of-government approach.

Implementing this plan will require significant new investment in challenging fiscal times. As of

December 2023, state revenues were projected to fall short of anticipated expenses for the next

few fiscal years. Meanwhile, initial estimates show that achieving an equitable transition to a clean

energy future could require a public sector investment of approximately $1 billion annually. The

federal government’s historic investment in climate solutions, through the Inflation Reduction Act

and other legislation, greatly bolsters Maryland’s chances of achieving its climate goals. However,

more investment will be needed. Additional funding will enable more Marylanders to buy electric

vehicles (EVs), install electric heat pumps, and otherwise switch to zero-emission devices that

eliminate fossil fuel use and shield consumers from volatile fossil fuel prices.

Specific investments proposed by this plan include:

● Home electrification incentives - Covering up to 100% of project costs for low and

moderate-income households and 50% of project costs for middle-income households to

convert to heat pumps, heat pump water heaters, and other home energy efficiency and

electrification products.

● EV incentives - Providing simple point-of-sale rebates to consumers to make EVs even

more affordable to buy and own.

● Commercial building incentives - Reducing the cost of energy efficiency and electrification

projects in commercial, multifamily, institutional, and other types of buildings .

4

● Infrastructure investments - Building out critical infrastructure, including EV charging

stations, and supporting projects that reduce GHG emissions from Maryland’s industrial

and waste sectors.

● Natural and working lands investments - Supporting tree plantings, forest management,

wetland management, soil management, and other projects that are critical for storing

carbon and helping the state achieve its net-zero emissions goals.

New investments will complement Maryland’s existing, substantial investment in renewable

energy and energy efficiency programs through the EmPOWER Maryland program, Regional

Greenhouse Gas Initiative, Renewable Portfolio Standard, and other existing programs.

While developing this plan, MDE held a series of seven listening sessions and obtained thousands

of comments from the public that were taken into consideration. One consistent theme reflected

in this plan is that the transition to a net-zero economy should be intentional but also practical and

methodical. This plan lays out a sustainable path where incentives are provided at key decision

points to consumers. For example, when a furnace needs to be replaced, a homeowner would have

access to incentives that make the decision to electrify economical. When it is time to replace a

gas-powered vehicle at the end of its useful life, consumers would have affordable options to

purchase an EV and easy access to a reliable charging network.

The following are the state’s current and new policies that, when taken together and fully

implemented, could achieve the 2031 emissions reduction goal.

1

Economywide

● Clean Economy Standard (new) - Directs the state to provide incentives, set sectoral

standards, and set economywide standards to reduce GHG emissions.

● Expanded Strategic Energy Investment Fund (current, modified) - Distributes funding

from Maryland’s participation in the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative and other

programs to provide incentives for decarbonization projects across different sectors of

Maryland’s economy.

● New Funding Sources (potential) - Provides approximately $1 billion annually for new

state investments in equitable climate action. See chapter 5 for more information.

1

“Current” means a policy that is adopted and does not need to be modified. “Current, modified” means a

current policy that needs to be modified. “New” means a policy that must be established through legislative

or executive action. “Potential” means a policy that requires additional consideration prior to adoption.

5

Electricity

● Renewable Portfolio Standard (current, modified) - Requires approximately 50% of

electricity consumed in Maryland to be generated by renewable resources by 2030 and

modifies definitions of qualifying resources.

● POWER Act (current) - Sets a goal for the state to build 8,500 megawatts of offshore wind

energy capacity by 2031.

● Energy Storage Act (current) - Sets a goal for Maryland to have 3,000 megawatts of energy

storage capacity by 2033.

● Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (current, modified) - Maryland’s existing cap and

invest program, which limits emissions from fossil fuel power plants and invests proceeds

in Maryland communities, generated $151 million in 2022. Maryland is advocating for a

stronger regional pollution cap aligned with Maryland’s and partner states’ 100% clean

energy goals in ongoing multistate deliberations and planning to remove offsets and

certain exemptions.

● Clean Power Standard (new) - Requires 100% of the electricity consumed in Maryland to

be generated by clean and renewable sources of energy by 2035.

● State Incentives for Renewable Energy (current) - Provides robust incentives for a wide

range of renewable energy projects.

Transportation

● Zero-Emission Vehicle Infrastructure Plan (current) - A comprehensive plan to further

develop Maryland’s charging infrastructure for zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs).

● Advanced Clean Cars II (current) - Requires 100% of new cars, light-duty trucks, and sport

utility vehicles (SUVs) sold in Maryland to be ZEVs by 2035.

● Advanced Clean Trucks (current) - Requires certain types of medium and heavy-duty

trucks sold in Maryland to be ZEVs in certain years.

● ZEV Transit Buses (current) - Requires state-owned transit buses to transition to ZEVs.

● ZEV School Buses (current) - Requires school districts to purchase or contract for the use

of ZEV school buses starting in 2024, provided that federal, state, or private funding is

available to cover incremental costs, relative to non-ZEV buses.

● Advanced Clean Fleets (potential) - Requires specific high-priority fleets of medium and

heavy-duty vehicles to transition to ZEVs.

● Maryland Transportation Plan (new) - Aims to reduce vehicle miles traveled per capita by

20% through infrastructure and programmatic investments.

● State Incentives for Purchasing EVs (current, modified) - Provides a point-of-sale rebate to

lower the upfront cost of buying new and used EVs and provides bonus rebates to low and

moderate income Marylanders.

6

Buildings

● Energy Codes and Standards (current) - Requires the state to adopt the latest version of

the International Energy Conservation Code, with possible amendment, within 18 months

of issuance.

● EV-Ready Standards for New Buildings (current, modified) - Requires EV charging

equipment to be installed during the construction of single-family detached houses,

duplexes, and townhouses, and extends new requirements to multifamily buildings.

● Building Energy Performance Standards (current) - Requires certain buildings 35,000

square feet or larger to achieve specific energy efficiency and direct emissions standards,

including achieving net-zero direct emissions by 2040.

● State Government Lead by Example (current) - Requires all-electric new construction and

other emission reduction measures for state-owned buildings.

● EmPOWER (current, modified) - Requires utility companies and the state government to

help customers improve energy efficiency and reduce GHG emissions, including through

beneficial electrification.

● Zero-Emission Heating Equipment Standard (new) - Requires new space and water

heating systems to produce zero direct emissions starting later this decade.

● Clean Heat Standard (new) - Requires clean heat measures to be deployed in buildings at

the pace required to achieve the state’s GHG reduction requirements.

● Gas System Planning (new) - Requires natural gas utility companies to plan their gas

system investments and operations for a net-zero emissions future.

● State Incentives for Building Decarbonization (current, modified) - Provides substantial

new funding for projects that improve energy efficiency and reduce emissions from

residential, commercial, and institutional buildings statewide.

Industry

● Hydrofluorocarbon Regulations (current) - Prohibits the use of certain products that

contain particular chemicals with high global warming potential.

● Control of Methane Emissions from the Natural Gas Industry (current) - Requires

methane emissions from natural gas transmission and storage facilities to be mitigated

through fugitive emissions detection and repair.

● Buy Clean (current) - Requires producers of cement and concrete mixtures to submit

environmental product declarations to the state and for the state to establish a maximum

acceptable global warming potential values for each category of eligible materials.

● State Incentives for Industrial Decarbonization (current, modified) - Supports

decarbonization activities in Maryland’s industrial sector.

7

Waste

● Landfill Methane Regulations (current) - Requires landfills to detect and repair landfill gas

leaks and operate emission control systems to reduce methane emissions.

● Food Residuals Diversion Law (current) - Requires businesses that generate at least one

ton of food residuals per week to separate the food residuals from other solid waste and

ensure that the food residuals are composted.

● Sustainable Materials Management (current) - Sets goals for GHG emissions reductions,

material-specific recycling rates, and overall statewide recycling and waste diversion rates.

● State Incentives for Waste Sector Decarbonization (current, modified) - Provides

substantial funding for waste sector decarbonization activities.

Agriculture

● State Incentives for Agricultural Decarbonization (current, modified) - Provides

additional funding for decarbonization activities in Maryland’s agricultural sector.

Forestry and Land Use

● Maryland 5 Million Trees Initiative (current) - Requires the state to plant and maintain five

million native trees in Maryland by 2031, with at least 10% of these trees located in urban

underserved areas of the state.

● Sustainable Growth (current) - Supports sustainable growth and land use/location

efficiency to minimize GHG emissions from future land development; fosters transit use,

walking, and biking; and reduces travel distances for daily mobility needs.

● Forest Management (current) - Promotes sustainable forestry management practices on

public and private forest lands in Maryland.

● Coastal Wetland Management (current) - Maximizes carbon sequestration and coastal

resilience benefits by protecting and restoring coastal wetlands.

● Agricultural Resource Conservation Programs (current) - Supports farmers in adopting

practices that improve soil health and increase carbon sequestration on agricultural lands.

● Forest Preservation and Retention Act (current) - Requires that when forested land is lost

to development, it is either replaced through planting new trees or compensated for

through conserving existing forest.

● State Incentives for Forestry and Land Use (current, modified) - Provides additional

support for activities that promote enhanced carbon sequestration in Maryland’s forestry

and land use sector.

8

Figure 1: Major Milestones on Maryland’s Decarbonization Timeline

The new policies in this plan are modeled to reduce statewide GHG emissions by 646 million

metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (MMTCO

2

e) between now and 2050. The societal benefit

of this level of emissions reduction is estimated to be $135 billion based on estimates for the social

cost of GHG emissions. As detailed in the plan, Maryland will add thousands of jobs and grow its

economy while delivering on its status as a global leader in addressing climate change.

Household energy costs will decrease significantly under this plan. Today, the average household

that uses heat pumps and drives EVs spends around $2,600 less annually in energy costs than

those with natural gas heating and gasoline-powered cars. Savings for the all-electric household

increase to around $4,000 annually compared to homes that are heated with oil or propane. Those

savings are projected to increase over time as fossil fuels become more expensive and electricity

rates remain comparatively stable. Robust federal and state incentives, paired with education,

technical assistance, and training for building owners, contractors, automobile dealers, and other

market actors, can help ensure that everyone can transition from fossil fuels and become part of

the clean energy economy.

9

This plan includes detailed economic and public health impacts, workforce development

opportunities, a funding plan, and implementation details such as the executive and legislative

actions that are needed for implementation. Much of the regulatory implementation falls on MDE,

which has the existing authority and legal obligation to adopt regulations to achieve the state’s

GHG reduction requirements, but all of Maryland state government has a role to play in

implementing the programs outlined. Importantly, the work ahead requires all Marylanders to

work together. The results will benefit us all and Maryland’s future for many years to come.

10

Maryland’s Climate

Pollution Reduction Plan

Policies to Reduce Statewide Greenhouse Gas Emissions 60% by 2031

and Create a Path to Net-Zero by 2045

Chapter 1: The Big Picture

Introduction

Maryland has long been a leader in addressing the cause of climate change, reducing greenhouse

gas (GHG) emissions faster than most other states while cleaning the air, improving public health,

and growing the economy.

In 2022, the Maryland General Assembly passed the Climate Solutions Now Act (CSNA),

establishing the most ambitious GHG reduction goals of any U.S. state. Maryland is now required

to reduce statewide GHG emissions 60% from 2006 levels by 2031 and achieve net-zero

emissions by 2045 while creating jobs and net economic benefits.

2

Net-zero emissions means that

the total GHG emissions from Maryland’s economy will be equal to the GHGs removed from the

atmosphere through natural and technological systems annually.

The policies in this plan, if fully implemented, are projected to achieve the 2031 goal and put

Maryland on a path to achieve net-zero emissions by 2045. The policies will nearly put an end to

the fossil fuel era and accelerate the transition to a clean energy economy. In turn, the state will

experience improved air quality, health, wealth, and the prospect of keeping our planet habitable

for future generations.

An all-of-society approach is needed to achieve these goals. Many Marylanders are still dependent

on fossil fuels. Until now, cost barriers to cutting ties with oil and gas have kept the clean energy

transition out of reach for too many. As innovation drives advancement that leads to lower prices,

more reliability, and more options, this plan includes protections for Marylanders with limited

resources, to ensure that everyone has access to a clean energy future.

Clean air, a stable climate, and more green jobs are opportunities for the state to prosper. The

policies in this plan not only constitute action to avert disaster; they place Maryland in a better

position to compete economically.

2

Maryland Senate Bill 528. Climate Solutions Now Act of 2022.

https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/2022RS/bills/sb/sb0528E.pdf .

11

From the Dirtiest Air to the Cleanest

Air pollution became a public health crisis over the last century as buildings, power plants,

vehicles, and industry released massive amounts of harmful chemicals into the atmosphere.

Marylanders suffered the effects of air pollution more than other Americans. In fact, Maryland

once held the dubious distinction of having some of the worst air quality east of the Mississippi

River.

Maryland’s air is much cleaner today. In 2022, the state met all national air quality standards for

the first time since the Clean Air Act (CAA) and National Ambient Air Quality Standard (NAAQS)

were established over 50 years ago.

3

This is a huge milestone.

Studies show that poor air quality creates public health issues and environmental consequences.

Even at low concentrations, certain air pollutants can trigger a variety of health problems, such as

asthma attacks, coughing, lung irritation, and increased susceptibility to longer-term illnesses such

as cardiovascular diseases. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) calculates that the

benefits of clean air are up to 90 times greater than the costs of reducing air pollution.

4

Maryland has made tremendous progress in achieving cleaner air over the last few decades.

Despite this progress, there are still too many days when haze settles over our cities and towns

and air quality warnings are issued. Too many children and adults are still hospitalized each year

with respiratory issues that are triggered by air pollution. Too many cars, trucks, buildings,

factories, and power plants are still emitting harmful pollution.

The policies in this plan are primarily designed to address climate change, but they will also

improve the health of Marylanders and make Maryland’s air some of the cleanest in the country.

We will also grow our economy by creating more green jobs and reducing energy costs for

businesses, homes, schools, and commercial buildings. The transition to a clean energy economy

requires millions of fuel-burning devices to be replaced with efficient, zero-emission alternatives.

The jobs we need are local. Replacing a boiler in someone’s basement can’t be outsourced.

Maryland’s Climate Pathway

The University of Maryland (UMD) Center for Global Sustainability was contracted by MDE to

evaluate options for achieving the state’s requirements to reduce GHG emissions and, with

supplemental analysis from the Regional Economic Studies Institute at Towson University (TU),

4

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Benefits and Costs of the Clean Air Act 1990-2020, the Second

Prospective Study.

https://www.epa.gov/clean-air-act-overview/benefits-and-costs-clean-air-act-1990-2020-second-prospect

ive-study .

3

The Maryland Department of the Environment. 2022 Air Quality Progress.

https://mde.maryland.gov/programs/workwithmde/Documents/AQCAC/2023MeetingMaterials/AQCAC%

20AQ%20Progress%202022%20FINAL.pdf .

12

identify economic impacts from these actions. In June 2023, MDE and UMD released Maryland’s

Climate Pathway, a report showing a package of policies that could achieve the state’s climate

goals.

5

The report found:

● Current policies will reduce emissions 51% by 2031 - Current policies include Advanced

Clean Cars II, Advanced Clean Trucks, Building Energy Performance Standards,

EmPOWER, Renewable Portfolio Standard, etc., also federal policies and investments such

as those made possible by the Inflation Reduction Act.

● Adding new sectoral policies could reduce emissions 56% by 2031 - New sectoral policies

include Advanced Clean Fleets, Clean Power Standard (100% clean power by 2035),

Zero-Emission Heating Equipment Standard, etc.

● Adding economywide policies to new sectoral policies could reduce emissions 60% by

2031 - New economywide policies, such as a cap and invest program, could be necessary

for Maryland to achieve its emissions reduction goals.

MDE and UMD hosted seven public listening sessions from July to September 2023. The

community was invited to participate in policy-making by testifying and submitting comments.

Thousands of people participated in the sessions or submitted written comments. Feedback was

carefully considered and often included in this report.

The Moore-Miller Administration, through MDE and other state agencies, is advancing the actions

in this plan based on the findings of, and public response to, Maryland’s Climate Pathway, findings

of countless other studies, and the state’s long history of developing and implementing policies to

achieve the state’s GHG reduction goals. Maryland will continue leading the transition to a clean

energy economy by using the best science, data, and practicality.

Investing Now for a Bright Future

This plan presents a significant expansion of existing programs aimed at helping Marylanders,

Maryland businesses, and state and local governments convert to energy-efficient systems. In the

long run, these conversions will result in significant cost savings. In the near term, they require a

significant infusion of up-front funding at a time when the Department of Legislative Services is

projecting a $418 million budget shortfall for the state’s Fiscal Year 2025 that could grow to $1.8

billion by FY28.

6

The Administration and the General Assembly have some options for how and when to implement

this plan to generate the additional funding needed to implement all of the policies and achieve the

6

The Maryland Department of Legislative Services. Effect of the 2023 Legislative Program on the Financial

Condition of the State. https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/pubs/budgetfiscal/2023rs-fiscal-effects.pdf .

5

The Maryland Department of the Environment and University of Maryland Center for Global

Sustainability. 2023. Maryland’s Climate Pathway. https://www.marylandsclimatepathway.com/ .

13

climate goals. Chapter 5, “Funding the Transition,” introduces a few options that will be further

developed and vetted in 2024.

The state is serious about leaving no one behind in this transition. This plan proposes to help

Marylanders ramp up purchases of EVs, heat pumps, and other zero-emission devices that

eliminate fossil fuel use and shield people from fossil fuel price impacts. The majority of state

spending would focus on providing financial support to Maryland’s low, moderate, and middle

income households and small businesses. Improving equity and affordability would be the primary

objectives of these investments. In short, the state would provide:

● Home electrification incentives - Covering up to 100% of project costs for low and

moderate income households and 50% of project costs for middle income households.

● EV incentives - Making EVs the lowest-cost vehicles to purchase and own, and making

them accessible to everyone.

● Commercial building incentives - Reducing the cost of energy efficiency and electrification

projects in commercial, multifamily, institutional, and other types of buildings.

● Infrastructure investments - Supporting projects that reduce GHG emissions from

Maryland’s industrial and waste sectors, and building out critical infrastructure including

EV charging stations.

● Natural and working lands investments - Supporting tree plantings, forest management,

wetland management, soil management, and other projects that are critical for storing

carbon and helping the state achieve its net-zero emissions goals.

As decisions must be made in light of projected budget challenges, the state will increase the focus

on funding transportation projects that reduce dependence on single-occupancy vehicles. The

Maryland Department of Transportation’s (MDOT) initiatives include enhancing existing

transportation infrastructure such as transit lines and clean buses, programs to reduce

single-occupancy trips, and actively catalyzing transit-oriented development to help support

housing and economic development. MDOT will ramp up investments and policies to

accommodate bicyclists and pedestrians routinely and safely on our extensive road network by

retrofitting streets with bike lanes, sidewalks, and traffic calming measures.

MDOT has already made significant investments to help reduce vehicle miles traveled (VMT),

however, additional VMT reduction measures are necessary to meet GHG reduction goals.

MDOT’s draft 2050 Transportation Plan includes an objective to reduce VMT per capita by 20%,

which will guide transportation project selection and development.

7

Additional investments and

sources of funds, such as federal programs, may be necessary to meet these VMT reduction goals.

7

The Maryland Department of Transportation. 2050 Maryland Transportation Plan.

https://www.mdot.maryland.gov/tso/pages/Index.aspx?PageId=22 .

14

Transitioning Away from Fossil Fuels

Billions of dollars in investments from the Inflation Reduction Act and other sources are already

converging with current federal and state policies to transition to zero-emission vehicles,

buildings, electricity sources, and more. New policies and investments will quicken the pace of

decarbonization. Maryland is systematically and responsibly replacing antiquated fuel-burning

systems including coal-fired power plants, internal-combustion engines, and gas-fired heating

equipment with cleaner technologies that have lower operating costs than their fuel-burning

alternatives. An analysis of the policies in this plan finds that fossil fuel use in Maryland will

decrease around 80% between now and 2045. The state will continue to develop policies, beyond

those included in this plan, to meet the global ambition to fully transition away from fossil fuels.

8

What this Plan Is and Is Not

This plan meets the legal requirements under Maryland Code, Environment Article, Title 2,

Subtitle 12, § 2-1205, § 2-1206, and § 2-1207, which requires MDE to adopt a final plan including

current and new policies that, if fully implemented, will reduce statewide GHG emissions 60% by

2031 and create net economic benefits for the state. This plan does not include every detail of new

policies or funding sources. Many details of this plan must be worked out by the agencies and

legislative committees responsible for developing new policies and through the extensive

stakeholder processes often required to adopt new legislation or regulation. While striving to

meet these goals, the legislature and implementing agencies should continue to consider ways to

manage and mitigate cost impacts to Marylanders.

This plan focuses on how to reduce emissions. While some of these same actions can support

climate change adaptation and resilience, this plan is not offered as a comprehensive strategy to

make Maryland more resilient to climate change impacts. In the near term, Maryland’s climate will

continue to get warmer, wetter, and wilder regardless of how this plan is implemented. Sea levels

will continue rising. Maryland’s low-lying farms will be increasingly affected by saltwater intrusion.

Islands throughout the Chesapeake Bay and much of Dorchester County will be lost to the sea by

the end of this century. Maryland’s climate in 50 years could resemble Mississippi’s climate today.

The impacts of climate change will be a defining feature of the 21st century. This plan focuses on

how to stop digging the hole we are in. Other efforts, including Maryland’s forthcoming Next

Generation Adaptation Plan and State Resilience Strategy, will address how to climb out as the

walls of the hole start crumbling.

8

United Nations, Framework Convention on Climate Change, Conference of the Parties serving as the

meeting of the Parties to the Paris Agreement. First Global Stocktake. Released December 13, 2023.

https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cma2023_L17_adv.pdf.

15

Chapter 2: The Policies

This chapter includes current and new policies that MDE and other state agencies have committed

to implement or explore. Some of the policies require additional legislative action. A summary of

the executive and legislative actions that are needed to implement the new policies in this chapter

is provided in Chapter 6.

Maryland has just seven years to transform its economy to achieve the 2031 goal and just 21 years

to finish the transformation to achieve net-zero emissions. There is no time for delay.

Economywide

Clean Economy Standard (new)

Maryland’s Clean Economy Standard is an umbrella policy that directs the state to:

1. Provide Incentives - Target investments in clean electricity, clean buildings, clean vehicles,

and clean industry in communities throughout the state, especially overburdened and

underserved communities.

2. Set Sectoral Standards - Establish regulatory standards to ensure critical actions are taken

in each sector of the economy.

3. Set Economywide Standards - Consider expanding Maryland’s cap and invest program or

developing new revenue-generating policies to complement targeted investments and

sectoral standards, while providing a sustainable revenue source for state-funded

community investments.

The Clean Economy Standard is the framework for Maryland’s comprehensive approach to

decarbonizing the entire economy. The incentives, sectoral standards, and economywide

standards covered by the Clean Economy Standard are explained in more detail below.

Expanded Strategic Energy Investment Fund (current, modified)

The existing Strategic Energy Investment Fund (SEIF),

9

used to allocate proceeds from the

Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative and other sources, will be used to distribute revenues from

new or expanded climate pollution reduction programs. New investments from SEIF will stimulate

Maryland’s economy and help consumers, businesses, local governments, farmers, and foresters

invest an estimated $1 billion annually into measures that reduce reliance on fossil fuels, deploy

clean energy solutions, and sequester more carbon in Maryland’s natural and working lands. New

investments will support:

9

The Maryland Energy Administration. Strategic Energy Investment Fund (SEIF).

https://energy.maryland.gov/Pages/Strategic-Energy-Investment-Fund-(SEIF)-.aspx .

16

● Home Energy Efficiency and Electrification Incentives

● Commercial, Multifamily, and Institutional Building Incentives

● EV and Charging Infrastructure Incentives

● Industry, Public Infrastructure, and Nature-Based Solutions Incentives

Public sector investments will leverage additional private sector investments, adding billions of

dollars to the state’s economy this decade. This will be a major economic stimulus for Maryland

once the state determines the best funding mechanism to make these investments.

New Funding Source (potential)

Emissions and economic modeling conducted by UMD and TU for Maryland’s Climate Pathway

and this plan show that a new economywide policy could be necessary for the state to achieve its

goals. A cap and invest policy was modeled for the Pathway report and this plan to establish a

regulatory cap on climate pollution from certain sources and use revenue from the sale of carbon

allowances for investments in clean energy projects, consumer rebates, and other decarbonization

programs. The state must further consider if cap and invest or another policy is best for Maryland.

Modeling shows that a policy that would require polluters to pay for their pollution and provide at

least $1 billion per year for clean economy investments could be critical for Maryland to achieve a

60% reduction in GHG emissions by 2031. Chapter 5 provides a few options for the state to

consider. To achieve the state’s emissions goals, the new policy would need to reduce annual GHG

emissions by 3.5 million metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent (MMTCO2e) in 2031, and 15.6

MMTCO2e in 2045.

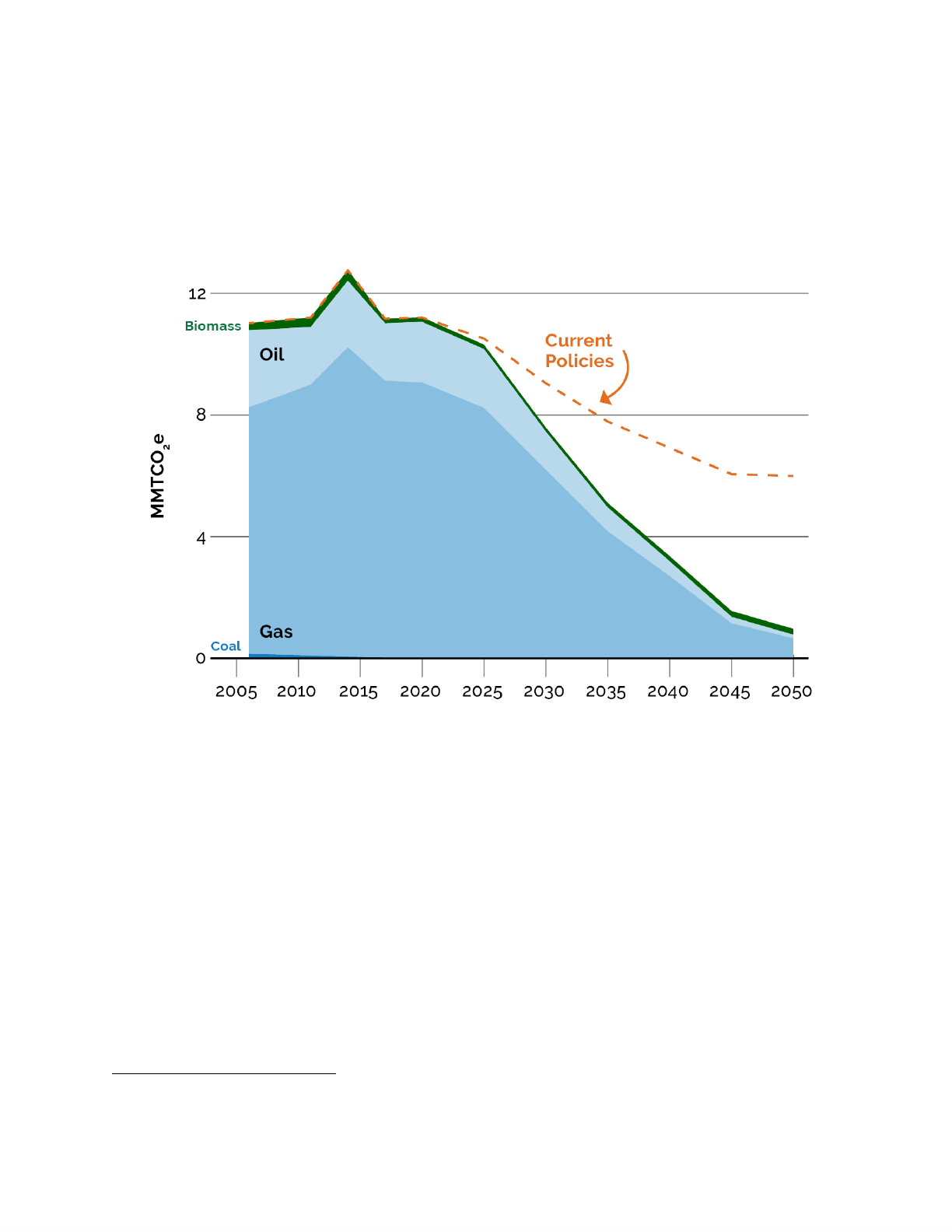

Impact of Economywide Policies

The economywide policies listed above work with the sectoral policies listed below to achieve

Maryland’s GHG reduction goals. In the aggregate, the economywide and new sectoral policies are

projected to reduce statewide GHG emissions by 646 MMTCO

2

e between now and 2050. The

societal benefit of this level of emissions reduction is estimated to be $135 billion. Figure 2

illustrates the change in GHG emissions and sequestration based on historical and modeled

trends.

17

Figure 2: Maryland’s statewide GHG emissions and sequestration trends , historical and

projected, from 2006 to 2050 based on current and new policies

Electricity

In 2020, electricity consumption accounted for 21% of Maryland’s gross GHG emissions.

10

While

this may seem like a large amount, the electricity sector has made significant progress since 2006,

when it accounted for 35% of emissions. The GHG reductions in this sector can be attributed to

programs that reduce total electricity demand, programs aimed at reducing the carbon intensity of

the electricity consumed, and wholesale electricity market trends, including the large-scale

replacement of coal-fired power plants with cleaner sources of electricity.

Reduced energy demand results from energy efficiency and conservation, which is driven in

Maryland by the EmPOWER Maryland program,

11

building energy codes and standards, and other

policies. To reduce the carbon intensity of the electricity generated, the state relies on the

Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS)

12

and other clean energy initiatives to incentivize renewable

energy generation. In addition, RGGI and other pollution control programs reduce carbon dioxide

12

The Maryland Public Service Commission. Maryland Renewable Energy Portfolio Standard Program -

Frequently Asked Questions.

11

The Maryland Energy Administration. EmPOWER Maryland.

https://energy.maryland.gov/pages/facts/empower.aspx .

10

The Maryland Department of the Environment. Greenhouse Gas Inventory.

https://mde.maryland.gov/programs/air/climatechange/pages/greenhousegasinventory.aspx .

18

(CO

2

) emissions from fossil fuel-fired energy generation, also impacting the carbon intensity of the

electricity. The combination and interaction between these programs lowers the emissions

intensity of both in-state electricity generation and imported electricity.

To achieve deeper reductions in emissions from the electricity sector, Maryland intends for 100%

of the electricity consumed in-state to be clean by 2035. This goal will be achieved through the

deployment of grid-scale and rooftop solar panels, offshore wind, hydropower, nuclear power, and

energy storage technologies that incorporate load flexibility and dispatchability into the electric

grid as sectors electrify to create a more manageable system. Additionally, new statewide

transmission and distribution infrastructure must be built while existing infrastructure is updated

to enhance the electric grid, improve the efficiency and delivery of electricity, and facilitate the

integration of renewable energy with a priority on clean resources. Ultimately, emerging

technologies in the electricity sector must be identified and evaluated to develop solutions for

zero-emission dispatchable technologies to meet demand and maintain reliability.

Reaching Maryland’s clean energy goals is made easier with incentives funded through the

Inflation Reduction Act (IRA)

13

. The Renewable Energy Production Tax Credit is an IRA-funded

program providing a per kilowatt-hour tax credit for electricity generated by solar and other

qualifying technologies for the first 10 years of a system’s operation. The Investment Tax Credit

reduces federal income tax liability for a percentage of the cost of an eligible renewable energy

system that is installed during the tax year. Importantly, the IRA also expanded the eligibility for

these tax credits, so they can now be utilized by tax-exempt entities and local governments

through direct pay provisions, by homeowners installing rooftop solar or residential wind systems,

and by more traditional commercial entities. Both tax credits also receive bonuses for domestic

content and siting in an energy community.

Renewable Portfolio Standard (current, modified)

Maryland’s Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) requires Maryland electric suppliers to provide

increasingly large proportions of Maryland's electricity from renewable energy sources like solar,

wind, hydropower, and qualifying biomass.

14

The program is implemented through the creation,

sale, and transfer of Renewable Energy Credits (RECs). The current RPS goal is for 52.5% for

non-municipal utilities and 20.4% for municipal utilities of Maryland's electricity to come from

renewable sources by 2030 through increases in solar power, deployment of new offshore wind

energy off the Atlantic coast, and geothermal energy.

To effectively decarbonize Maryland’s electricity supply, the state intends to increase the

deployment of clean and renewable energy resources through the RPS and other clean energy

14

Public Service Commission. Renewable Energy Portfolio Standard Program.

https://www.psc.state.md.us/electricity/maryland-renewable-energy-portfolio-standard-program-frequentl

y-asked-questions/ .

13

White House. Inflation Reduction Act Guidebook.

https://www.whitehouse.gov/cleanenergy/inflation-reduction-act-guidebook/

19

initiatives while reducing CO

2

emissions from energy generation through RGGI and other

pollution control programs. Maryland’s 2030 Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reduction Act (GGRA)

Plan advanced measures to accelerate the deployment of clean energy that have not been

enacted, including a proposed Clean and Renewable Energy Standard (CARES), to achieve 100%

clean electricity in Maryland by 2040.

15

The 2030 GGRA Plan projected substantial increases in

the rate of clean energy deployment as a result of those measures and a coincident decrease in

fossil fuel-fired generation. Maryland will need to increase its deployment of clean energy

resources to reach the projections in this plan and achieve the new goal of a 60% reduction in

statewide GHG emissions by 2031. This plan calls for the CARES proposal to be replaced with a

Clean Power Standard that would achieve 100% clean electricity by 2035, as described later in

this chapter.

The state is not meeting the RPS goals and more challenges remain. Maryland has seen setbacks to

deploying solar and wind energy for various reasons, namely delays in offshore wind development

and siting and supply chain issues creating impediments to solar development. The achievement of

changes in Maryland’s generation mix will be impacted by the federal agencies that oversee the

power markets from which Maryland procures electricity. A backlog of projects awaiting approval

by the PJM Interconnection, the regional transmission organization in which Maryland

participates, has contributed to the issue.

Offshore wind will be a reliable clean energy resource available to the state. The Maryland

Offshore Wind Energy Act of 2013 created an offshore wind carveout of Tier 1 resources under

the RPS of a maximum of 2.5% of electricity sold in Maryland in 2017, and later.

16

The Clean

Energy Jobs Act (CEJA) added a second round of offshore wind procurement for a minimum of an

additional 1,200 megawatts (MW) with a residential cap of annual bills to protect ratepayers.

17

The Maryland Public Service Commission (PSC) has approved four major wind projects to be built

more than a dozen miles off the Maryland coast between the first and second rounds of

applications.

To support the growth of a healthy offshore wind industry, the state must continue to work with

neighboring states, federal agencies, and local municipalities to design and deploy offshore and

onshore transmission systems to integrate the large number of offshore wind projects anticipated

in the waters of the East Coast. To do so, Maryland will continue to lead in the discussions of the

Regional SMART-Power partnership with other coastal states.

Under the CEJA and through the SMART-Power partnership, Maryland aims to expand education

and training programs to grow a new offshore wind workforce, expand local supply chains, support

17

Maryland Senate Bill 516. Clean Energy Jobs.

https://energy.maryland.gov/Pages/Info/renewable/offshorewind.aspx .

16

The Maryland Energy Administration. Offshore Wind Energy in Maryland.

https://energy.maryland.gov/Pages/Info/renewable/offshorewind.aspx .

15

The Maryland Department of the Environment. 2030 GGRA Plan.

https://mde.maryland.gov/programs/air/ClimateChange/Documents/2030%20GGRA%20Plan/THE%202030%20GGRA%20PLAN.pdf

20

the redevelopment of and improvements to critical port infrastructure, and advance research and

innovation. In addition, Maryland will work with the U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of

Ocean Energy Management to explore the expansion of offshore wind lease areas in federal

waters.

Under this plan, RPS will continue to require that approximately 50% of electricity consumed in

Maryland will be generated by renewable sources by 2030. RPS will also link with a new Clean

Power Standard to achieve the Administration’s goal for 100% of the electricity consumed in-state

to be clean by 2035. This plan calls for the definitions of qualifying resources in the RPS program

to align with definitions of clean power resources under the forthcoming Clean Power Standard,

including the elimination of eligibility for municipal solid waste incineration. Legislation will be

needed to change the RPS definitions, which are set in the state’s statute.

POWER Act (current)

The Promoting Offshore Wind Energy Resources (POWER) Act became effective June 1, 2023.

18

The POWER Act sets a state goal of reaching 8,500 megawatts (MW) of offshore wind energy

capacity by 2031 and anticipates the issuance of sufficient wind energy leases in the central

Atlantic region to satisfy that goal. Offshore wind can provide clean energy at the scale needed to

help achieve Maryland’s economywide net-zero GHG emissions reduction goal. The POWER Act

intends to upgrade and expand the transmission system to accommodate the buildout of at least

8,500 MW of offshore wind energy from qualified projects and maximize the opportunities for

obtaining and using federal funds for offshore wind and related transmission projects.

PSC, in consultation with MEA, is required by the POWER Act to request that PJM

Interconnection analyze specified offshore wind transmission system expansion options. Either

the PSC or PJM must issue and evaluate competitive solicitations for proposals for related

projects. The PSC may then accept one or more proposals, subject to specified criteria.

Additionally, the POWER Act provides an alternative procurement mechanism to finance the

remaining space in the original two lease areas owned by Orsted and US Wind. Through that

procurement approach, the Maryland Department of General Services (DGS) must issue a

procurement and may enter into at least one long-term power purchase agreement for up to 5

million megawatt-hours annually of offshore wind energy. Round 1 and 2 offshore wind

developers may apply to PSC for a full or partial exemption from the requirement to pass along

certain federal benefits to ratepayers.

Energy Storage Act (current)

The Energy Storage Act of 2023 established a goal for Maryland to have 3,000 megawatts of

energy storage by 2033. Energy storage devices include thermal storage, electrochemical storage,

virtual power plants, and hydrogen-based storage. The law requires PSC to implement a Maryland

18

Maryland Senate Bill 781. Offshore Wind Energy - State Goals and Procurement (Promoting Offshore

Wind Energy Resources Act). https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/2023RS/bills/sb/sb0781E.pdf

21

Energy Storage Program to cost-effectively procure energy storage over the next decade. PSC

issued Order No. 90823 on October 2, 2023, initiating a workgroup to develop a Maryland Energy

Storage Program and docketed Case No. 9715 to develop this program.

Community Solar Act (current)

The Community Solar Pilot Program was established in 2015. This pilot program limited overall

community solar capacity to 583 megawatts, including 52.5 megawatts dedicated for low and

moderate income (LMI) customers, which amounted to only a small percent (<5%) of the state’s

electricity load.

19

House Bill 908 of 2023 passed with the Governor’s signature making the

Community Solar Program permanent. It requires community solar projects constructed under

the permanent program to dedicate 40% of energy output to LMI subscribers. In addition, House

Bill 908 removes the cap on the amount of community solar capacity that Maryland can deploy,

constraining it only by the state's statutory net energy metering limit of 3,000 megawatts. PSC is

implementing the permanent program through its Net Energy Metering Workgroup and upcoming

rulemaking. PSC discusses the current state of Community Solar and Net Metering in its Net

Metering Report, which is filed annually with the Maryland General Assembly.

Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (current, modified)

RGGI is a collaborative program among 11 East Coast states to reduce CO

2

emissions from power

plants through a regional cap and invest program. These states adopted market-based CO

2

cap

and invest programs designed to reduce emissions from fossil fuel-fired electric power generators

with a nameplate capacity of 25 megawatts or greater. Thanks to its success, RGGI has grown

substantially in recent years, with New Jersey renewing its participation in the program in 2020,

Virginia joining in 2021, and Pennsylvania proposing regulations in 2022 to begin participation.

20

RGGI is currently composed of Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, New

Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Virginia. Participating RGGI states

require fossil fuel-fired electricity generators to have acquired, through a regional auction or

secondary market transactions, one CO

2

allowance for every short ton of CO

2

emitted over a

three-year compliance period. Maryland has participated in RGGI since the program’s inception in

2007. Through RGGI, the participating states have cut power plant emissions in half while enjoying

billions of dollars of economic benefit and creating thousands of jobs.

As a RGGI participating state, Maryland caps and reduces CO

2

emissions from in-state fossil fuel

electricity generators. The 2030 GGRA Plan identified the expansion of the RGGI partnership to

additional states, especially Maryland’s neighbors in PJM territory, as a priority measure to reduce

the emissions intensity of Maryland’s imported power. RGGI has successfully welcomed new

members to the program in recent years, substantially improving its coverage of the PJM region

and dramatically improving the impact on carbon pollution in the region, including cleaning

20

Pennsylvania’s program is currently on hold pending litigation.

19

The Maryland Energy Administration. Maryland Community Solar.

https://energy.maryland.gov/Pages/MarylandCommunitySolar.aspx .

22

Maryland’s imported power. RGGI states largely recognize that all participating states can benefit

from a broader market with more participants. Larger markets increase economic efficiency and

cost-effectiveness, align more closely with the regional nature of the PJM transmission grid and

can help drive even greater consumer savings.

RGGI participating states reinvest the proceeds from the quarterly CO

2

allowance auctions in

consumer benefit programs to improve energy efficiency and accelerate the deployment of

renewable energy technologies. Maryland allocates proceeds from the sale of CO

2

allowances into

SEIF - a special, non-lapsing fund administered by MEA. MEA deploys SEIF funds to promote

affordable, reliable, and clean energy across Maryland’s diverse regions and communities while

reducing energy bills, creating jobs in growing industries, helping to reduce GHG emissions,

increasing resiliency, and promoting energy independence.

RGGI sets a binding cap on CO

2

emissions from power plants in the region that reduces every year.

The 2030 GGRA Plan proposed to reduce the RGGI cap to zero by 2040, with cost controls. Due to

Maryland’s new statewide GHG emissions reduction requirements and the historic investments

made by the federal government in clean energy development, Maryland has upped its ambition

for RGGI. In the current RGGI Program Review process, where the RGGI participating states

convene to establish the program’s future goals, Maryland is now advocating for the RGGI cap to

be strengthened to be consistent with states’ 100% clean energy goals. The participating states

are expected to reach an agreement on a new program structure in 2024. If the outcome of the

multistate agreement is not sufficiently stringent to meet the goals of the Climate Solutions Now

Act, MDE will consider additional complementary regulations.

MDE, which enforces Maryland’s regulations for RGGI participation, will also eliminate

underutilized components of the program including offsets and the Limited Industrial Exemption

Set Aside when it updates its CO

2

Budget Trading Program regulation in 2024.

Clean Power Standard (new)

To achieve Governor Moore’s commitment to achieve 100% clean power by 2035, strengthen

Maryland’s status as a climate leader, and support the goal of reducing statewide GHG emissions,

the Administration and state agencies are developing a Clean Power Standard (CPS).

CPS is a policy that will complement the RPS to ensure that all electricity consumed in the state is

generated by clean and renewable sources of energy by 2035. Although the policy is still in

development, it will likely allow for solar, wind, hydro, nuclear, energy storage, and other

zero-emission technologies to qualify as clean energy sources, while eliminating existing eligibility

and subsidies for municipal solid waste incineration.

MEA, MDE, the Maryland Department of Natural Resources (DNR) Power Plant Research

Program (PPRP), the Maryland Public Service Commission (PSC), and the Office of People’s

Counsel (OPC) will determine the best approach to a potential rulemaking. The state agency

23

partnership will design requisite components, timing, and milestones for outcomes of a potential

regulation, including responsible agency; designing supportive and/or complementary policy;

identifying the relevance of existing and proposed federal policy; and identifying key stakeholders

for their perspectives on a potential rule framework.

The partnership will also address any economic and ratepayer impact. Ideally, a CPS would have

minimal impact on electricity rates and promote public and private investment within the state.

The goal is to design a program that mitigates potential ratepayer impacts, ensuring that existing

inequities are remediated while stimulating economic growth within the state. Challenges related

to generation deployment within the RPS will likely apply to CPS implementation as well.

CPS, as modeled for this plan, would avoid annual GHG emissions of 0.9 MMTCO

2

e in 2031, and

2.5 MMTCO

2

e in 2045.

State Incentives for Renewable Energy (current)

Over the years, Maryland has hosted a wide range of incentives to encourage the new

development of renewable energy projects. The Maryland Clean Energy Center (MCEC) provides

public-private and public-public partnerships, including through leading Commercial Property

Assessed Clean Energy (C-PACE),

21

the Maryland Clean Energy Capital Program (MCAP),

22

and the

Clean Energy Advantage (CEA) Loan Program.

23

The state also administers the Maryland Energy

Storage Income Tax Credit Program and the Maryland Solar System Sales Tax Exemption.

24

Local

governments have created Green Banks, Finance Authorities, and Energy Conservation Tax

Credits.

One of the primary entities responsible for incentivizing renewable energy is MEA, which

manages various renewable energy programs under SEIF using revenue from RGGI and RPS

alternative compliance payments, which are incurred when insufficient RECs are available to meet

the RPS requirements, as well as other targeted non-SEIF renewable energy funds. Through

grants, rebates, loans, technical assistance, and education efforts, MEA is actively advancing solar,

offshore wind, land-based wind, and geothermal heating and cooling in Maryland. The eligibility

per program varies and may include individual homeowners, private businesses, municipal, local,

and state governments, and nonprofit organizations.

In Fiscal Year 2022, MEA hosted the following solar programs: the Solar Resiliency Hubs Grant

Program, Solar Canopy and Duel Use Technology Grant Program, the Community Solar

Low-to-Moderate Income Power Purchase Agreement Grant Program, the Community Solar

24

The Maryland Energy Administration. Maryland Energy Storage Income Tax Credit - Tax Year 2023.

https://energy.maryland.gov/business/Pages/EnergyStorage.aspx .

23

Clean Energy Advantage. https://cealoan.org/ .

22

Maryland Clean Energy Center. Maryland Clean Energy Capital Program.

https://www.mdcleanenergy.org/finance/mcap/ .

21

Maryland Clean Energy Center. MDPACE. https://www.mdcleanenergy.org/finance/md-pace/ .

24

Guaranty Grant Program, the Public Facility Solar Grant Program, the Low-Income Solar Grant

Program, and the Solar Technical Assitance Program. The Clean Energy Rebate Program also

provided incentives to residential and commercial customers to install solar photovoltaic (PV)

systems, as well as solar water heating, geothermal heating and cooling, and wood and pellet

stoves. The Offshore Wind Program includes the Capital Expenditure Program and the Workforce

Training Program, funded both by SEIF and the Offshore Wind Business Development Fund,

thereby providing support for research and building a supply chain.

Impact of Electricity Sector Policies

The new policies are modeled to reduce electricity sector GHG emissions by 128.9 MMTCO

2

e

between now and 2050. The societal benefit of this level of emissions reduction is estimated to be

$29 billion. Figure 3 illustrates the change in GHG emissions from this sector based on historical

and modeled trends.

Figure 3: Maryland’s electricity sector GHG emissions trends , historical and projected, from

2006 to 2050 based on current and new policies

25

Transportation

The transportation sector accounted for 35% of Maryland’s GHG emissions in 2020 with most

emissions (82%) in this sector coming from on-road vehicles powered by gasoline or diesel.

25

Non-road and other emissions, which are relatively minor compared with on-road emissions, come

from vehicles, including airplanes, trains, marine vessels, farming equipment, recreational vehicles,

and other motorized vehicles that do not operate on public roads.

On-road gasoline and diesel emissions have decreased steadily and will continue to decrease with

the influx of vehicles meeting federal Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards

26

and

increased demand for EVs. Emissions from heavy-duty diesel vehicles have remained consistent

since 2006 but the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) more stringent heavy-duty

engine and vehicle GHG standards will be fully implemented by model year 2027.

To achieve deeper reductions from the transportation sector, it will be necessary to transition

much of the light-duty fleet to ZEVs by 2031 and increase the use of other modes of

transportation, including public transportation and micro-mobility options. New charging

infrastructure will need to be developed and installed in conjunction with the retrofitting of

existing gas stations to support charging stations. Public transportation and mobility alternatives

must be enhanced, with an emphasis on promoting sustainable growth and other transit and

mobility-oriented development.

Zero-Emission Vehicle Infrastructure Plan (current)

To accomplish Maryland’s goal for rapid growth in the number of ZEVs on Maryland’s roads,

building out a robust ZEV infrastructure network is critical. As such, the Maryland Department of

Transportation’s (MDOT’s) National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) Plan, which was

developed in partnership with MEA, serves as the foundational first step for this strategic network

buildout.

27

MDOT submitted the Maryland State Plan for NEVI Formula Funding Deployment to

the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) in 2022, and the 2023 Update of the ‘NEVI Plan’ in

August 2023. The 2023 Plan Update, approved by FHWA in September 2023, describes

Maryland’s activities that support the successful deployment of charging infrastructure.

The NEVI Plan details the strategy for awarding $63M of NEVI funds to build out and certify

Maryland’s 23 EV Alternative Fuel Corridors (AFCs). This ensures that there will be reliable EV

infrastructure accessible to the traveling public, with a minimum of two stations per AFC capable

of charging four EVs simultaneously and located no more than 50 miles apart. MDOT anticipates

the addition of 40-48 charging sites along Maryland AFCs to achieve corridor build-out and

27

Maryland Department of Transportation. Maryland Zero Emission Vehicle Infrastructure Plan.

https://evplan.mdot.maryland.gov/?doing_wp_cron=1701708265.2618820667266845703125 .

26

The U.S. Department of Transportation National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Corporate

Average Fuel Economy. https://www.nhtsa.gov/laws-regulations/corporate-average-fuel-economy .

25

The Maryland Department of the Environment. Greenhouse Gas Inventory.

https://mde.maryland.gov/programs/air/climatechange/pages/greenhousegasinventory.aspx .

26

certification by FHWA. The NEVI Plan is updated annually. In its 2024 update of the NEVI Plan,

MDOT will address potential applications of NEVI funding to support MHDV/Trucking

infrastructure and investments in community charging to increase equitable charging access

across diverse locations in the state. Throughout this deployment, MDOT will prioritize

disadvantaged and rural communities, support workforce development, and collaborate closely

with public and private stakeholders. The remaining NEVI funds will then be invested in

community charging to increase equitable charging access across diverse locations in the state.

Advanced Clean Cars II (current)

Governor Moore took swift action in the first few months of his Administration to adopt

regulations that require car manufacturers to offer more zero-emission cars to consumers in

Maryland. This policy alone may do more than any other to reduce GHG emissions in Maryland.

Vehicles sold in the United States must be certified under one of two certification programs: the

federal program administered by EPA or the California program. Section 177 of the Clean Air Act

Amendments of 1990 provides states with the ability to adopt the California program instead of

the federal program as long as the adopted state program is identical to the California program

and the state allows two model years lead time from adoption to implementation.

The Maryland Clean Cars Act of 2007 required MDE to adopt regulations implementing the

California Advanced Clean Cars I (ACC I) program in Maryland. Maryland’s implementing

regulations adopted, through incorporation by reference, the applicable California regulations.

The ACC I program is a dynamic, changing program in which many of the relevant California

regulations are continuously updated to stay current with vehicular technology advancement and

environmental science. To retain California’s standards, Maryland must remain consistent with

their regulations, hence when California updates its regulations, Maryland must reflect these

changes by amending our regulations. The ACC I program included requirements for vehicles

through model year 2025.

The Advanced Clean Cars II (ACC II) program requires that by 2035 all new passenger cars, trucks,

and SUVs sold will be ZEVs.

28

The ACC II program takes the state’s already growing ZEV market

and robust motor vehicle emission control rules and augments them to meet more aggressive

tailpipe emissions standards and ramp up to 100% ZEV. The ACC II program adopts new

requirements for model year 2026 and later vehicles. Maryland’s implementation of the ACC II

program will begin with the 2027 model year.

The ACC II program will result in significant additional emission reductions in Maryland as

compared to the program currently in effect. Between 2027 and 2040, the updated program will

deliver additional vehicular reductions of 5,978 tons of nitrogen oxides (NO

x

) and 585 tons of fine

particulate matter 2.5 micrometers in diameter and smaller (PM

2.5

), as well as additional vehicular

28

The Maryland Department of the Environment. Advanced Clean Cars II.

https://mde.maryland.gov/programs/air/MobileSources/Pages/Clean-Energy-and-Cars.aspx .

27

and power plant CO

2

emission reductions of 76.7 million metric tons. By 2040, these reductions

provide net health benefits equal to about $604 million annually due to decreases in respiratory

and cardiovascular illness and associated lost work days.

The ACC II program applies to automobile manufacturers that produce new motor vehicles for

sale in Maryland. All vehicle types that have a gross vehicle weight rating of less than 14,000

pounds are affected.

Although there are a substantial number of conforming revisions, the major revisions associated

with the ACC II program consist of a requirement that vehicle manufacturers continue to offer

more ZEVs for sale, culminating in a 100% sales requirement by model year 2035, and a

requirement that internal combustion engine vehicles meet increasingly stringent pollutant

standards during the period in which they continue to be sold.

ZEVs consist of all-electric EVs with a minimum range of 150 miles and plug-in hybrid electric

vehicles (PHEVs) with a minimum all-electric range of 50 miles. PHEVs are allowed to satisfy 20%

of overall ZEV sales requirements. Additional flexibility options are available in model years 2027

through 2030. Vehicle manufacturers are also allowed to carry forward and use compliance

credits generated before model year 2027. To ensure that vehicles sold under the program are

reliable and perform as well or better than their internal combustion engine counterparts,

stringent requirements related to vehicle (and battery) durability, vehicle charging capability,

on-board diagnostics, warranty, and reporting are established to ensure that ZEVs perform as

designed throughout their full useful life.

Advanced Clean Trucks (current)

The Clean Air Act established the framework for controlling harmful emissions from mobile

sources. At the time, California had already established its own emission standards for mobile

sources, and so was granted the sole authority to continue adopting vehicle emission standards, so

long as they were at least as protective as the standards set by EPA.

The harmful emissions from medium- and heavy-duty trucks pose a serious threat to both public

health and climate change. Recognizing this, California has adopted the Advanced Clean Trucks

(ACT) regulation that aims to reduce on-road emissions from the medium- and heavy-duty truck

sector to a greater extent than the current EPA standards.

Section 177 of the Clean Air Act allows other states to adopt the California standards if they are

identical. Maryland’s Clean Trucks Act of 2023 requires MDE to exercise this authority and adopt

regulations implementing the California ACT program in Maryland. MDE adopted regulations in

2023 through incorporation by reference of the applicable California regulations.

The Clean Trucks Act of 2023 reinforces the state’s ongoing commitment to reducing climate

pollutants to reach the nation-leading goal of achieving a 60% reduction in GHG emissions by

28

2031. Medium- and heavy-duty trucks account for about a third of Maryland’s transportation

emissions. On-road diesel trucks are the largest contributor to NO

x

emissions in Maryland.

Adopting ACT in Maryland will result in a significant reduction of harmful emissions associated

with medium- and heavy-duty trucks and help Maryland attain its air quality goals. The ACT

program will reduce NO

x

, PM

2.5

, and GHG emissions from the mobile source sector as cleaner,

zero-emission trucks replace older internal combustion vehicles.

Zero-Emission Transit Buses (current)

Maryland is investing in transitioning its public transit bus fleet to ZEVs. The first seven electric

buses were delivered to the Maryland Transit Administration (MTA) in the Fall of 2023, and MTA is

contracting for up to 350 more over the next five years. In addition, MTA is working closely with its

electric utility provider, electric charging and power distribution suppliers, transit labor unions,

and employees to ensure a seamless transition to zero emissions that maintains reliable bus

service. Technology advances that increase the range of electric transit buses and increase

hydrogen fuel availability will be important components to successful transit fleet conversions in

Maryland.

Zero-Emission School Buses (current)

Transportation contributes more GHG emissions than any other sector, and the nation’s 480,000

school buses make up its single largest public transportation fleet — a fleet that millions of children

rely on to get to school safely (and far more efficiently than if every student were to drive on their

own). Approximately 90% of buses run on diesel fuel.

Switching over to electric fleets has become a goal for many cities and school districts. As of June

2023, there were 2,277 electric buses either on the streets or on order for school districts in the

U.S., according to the World Resources Institute. More than double that number are committed,

meaning that school districts plan to continue electrifying their fleets.

Federal funding from the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law has been crucial to this trend, largely

because one of the biggest barriers to electrifying school bus fleets is the price tag. The cost of an

electric bus can be about three times the cost of a diesel bus.

Montgomery County has the largest electric school bus project in the country, and it offers a

different model for the switch to electric buses. Rather than purchase its own buses, the county

partnered with a private contractor, which works with municipal partners to help manage the

process of adopting this new technology. This contractor works with Montgomery County to

secure funding — by applying to EPA grants, for instance — and then buys the buses from EV

manufacturers. The company essentially provides electrification as a service, from the hardware

of the buses themselves to the software that optimizes charging schedules. It is also responsible

for all repairs and maintenance, although the company offers training so that cities can keep their

29

existing staff and contracts. Montgomery County has set its sights on a fully electric fleet within

10 years. For its initial pilot, the county has committed to swapping 326 of its buses to electric by

2025, and 86 are already running.

Last fall, Baltimore City received $9.4 million from EPA’s Clean School Bus Program.

29

It was one of

nearly 400 school districts from across the country selected to receive funding for new buses, with

a focus on underserved areas and those overburdened by pollution, in keeping with President

Biden’s Justice40 goals. For Baltimore, going electric wouldn’t have been possible without the help

of the EPA grant.

The CSNA includes school bus electrification as a goal for the state. Under the CSNA, beginning in

fiscal year 2025, a county board of education may not enter into a new contract for the purchase

or use of any school bus that is not a zero-emission vehicle. There are exemptions for lack of

sufficient funding or availability of a vehicle that meets the performance requirements. The CSNA

also permitted electric utilities to provide rebates for school buses subject to certain limitations.

Baltimore is now preparing to launch its own pilot, following its neighbor’s model and partnering

with a private contractor. A depot with 25 charging stations was constructed in the summer of

2023. Twenty-five electric school buses are scheduled for delivery by the end of 2023. Baltimore

City’s contractor will offer training for the drivers on best practices for things like maximizing

energy efficiency, and then the buses can hit the road.

Advanced Clean Fleets (potential)

The California Advanced Clean Fleets (ACF) regulation applies to fleets performing drayage

operations (freight from an ocean port to a destination), those owned by state, local, and federal

government agencies, and high-priority fleets.

30

High-priority fleets are entities that own, operate,

or direct at least one vehicle in the state, and that have either $50 million or more in gross annual

revenues, or that own, operate, or have common ownership or control of a total of 50 or more

vehicles (excluding light-duty package delivery vehicles). The regulation affects medium- and

heavy-duty on-road vehicles with a gross vehicle weight rating greater than 8,500 pounds,

off-road yard tractors, and light-duty mail and package delivery vehicles. Under the ACF program,

covered fleets are required to make an increasing amount of their new purchases be ZEVs. These

ZEV purchase requirements are phased-in beginning in 2025. Between 2035 and 2042, all

covered fleets are required to make 100% of their new vehicle purchases ZEVs. This regulation

would work in conjunction with the ACT regulation, which helps ensure that ZEVs are brought to

market.

30

California Air Resources Board. Advanced Clean Fleets.

https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/our-work/programs/advanced-clean-fleets .

29

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Clean School Bus Program.

https://www.epa.gov/cleanschoolbus .

30

ACF is modeled to avoid annual GHG emissions of 1.8 MMTCO

2

e in 2045, however, more detailed

analysis is needed to determine the incremental emissions impact of ACF compared with ACT.

MDE would be responsible for developing, adopting, and implementing regulations to enact and