RESEARCH ARTICLE

Barriers and facilitators to qualitative data

sharing in the United States: A survey of

qualitative researchers

Jessica Mozersky

ID

1

*, Tristan McIntosh

1

, Heidi A. Walsh

ID

1

, Meredith V. Parsons

1

,

Melody Goodman

2

, James M. DuBois

1

1 Bioethics Research Center, Division of General Medical Sciences, Washington University School of

Medicine, St. Louis, MO, United States of America, 2 School of Global Public Health, New York University,

New York, NY, United States of America

Abstract

Qualitative health data are rarely shared in the United States (U.S.). This is unfortunate

because gathering qualitative data is labor and time-intensive, and data sharing enables

secondary research, training, and transparency. A new U.S. federal policy mandates data

sharing by 2023, and is agnostic to data type. We surveyed U.S. qualitative researchers (N

= 425) on the barriers and facilitators of sharing qualitative health or sensitive research data.

Most researchers (96%) have never shared qualitative data in a repository. Primary con-

cerns were lack of participant permission to share data, data sensitivity, and breaching trust.

Researcher willingness to share would increase if participants agreed and if sharing

increased the societal impact of their research. Key resources to increase willingness to

share were funding, guidance, and de-identification assistance. Public health and biomedi-

cal researchers were most willing to share. Qualitative researchers need to prepare for this

new reality as sharing qualitative data requires unique considerations.

Introduction

Qualitative health data—such as data from interviews or focus groups—are rarely shared in

the United States (U.S.) [1 p.161, 2]. This is unfortunate because qualitative data are labor and

time-intensive to gather, and data sharing would enable secondary research, enhance training,

and increase transparency. In contrast, qualitative data sharing is more common in places

such as the UK, Finland, Germany, and Australia [3, 4]. The UK Data Service is now a well-

established archive providing infrastructure and services to facilitate qualitative data sharing

with a collection of nearly 1000 data sets [3].

The National Institutes of Health (NIH), the largest federal funding body of health research

in the U.S., recently updated its policy for data management and sharing to increase data shar-

ing obligations and enforcement. The policy will take effect in 2023. NIH guidance states that,

‘data should be made as widely and freely available as possible while safeguarding the privacy

of participants, and protecting confidential and proprietary data’ [5]. The policy is agnostic to

data types, defining data broadly as ‘recorded factual material commonly accepted in the

PLOS ONE

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261719 December 31, 2021 1 / 13

a1111111111

a1111111111

a1111111111

a1111111111

a1111111111

OPEN ACCESS

Citation: Mozersky J, McIntosh T, Walsh HA,

Parsons MV, Goodman M, DuBois JM (2021)

Barriers and facilitators to qualitative data sharing

in the United States: A survey of qualitative

researchers. PLoS ONE 16(12): e0261719. https://

doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261719

Editor: Quinn Grundy, University of Toronto,

CANADA

Received: July 29, 2021

Accepted: December 8, 2021

Published: December 31, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Mozersky et al. This is an open

access article distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons Attribution License, which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and

reproduction in any medium, provided the original

author and source are credited.

Data Availability Statement: The de-identified

survey data underlying the results reported here

are included with this manuscript as Supporting

Information.

Funding: This project is funded by the National

Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI https://

www.genome.gov) R01HG009351 (PI DuBois)

(JM, TM, HW, MP, MG, JD) and the National

Center for Advancing Translational Sciences

(UL1TR002345 https://ncats.nih.gov) (JM, TM,

MP, JD). The funders had no role in study design,

scientific community as necessary to validate and replicate research findings’ including unpub-

lished data [5]. This policy is noteworthy because funded researchers frequently share quanti-

tative data to comply with NIH policy, but the revised policy will require data sharing of all

types of data, potentially leaving qualitative researchers unprepared for the coming reality.

Our prior work has identified a series of benefits and concerns regarding qualitative data

sharing (QDS). It could increase the transparency of research and enable verification of find-

ings, which can foster public trust [1, 2, 6–8]. Sharing data enables secondary users to explore

new research questions, or collate findings across multiple studies, maximizing the value of

data that are often costly and resource intensive to collect. QDS may reduce participant burden

by allowing researchers to use existing data rather than collect new data. QDS also provides an

opportunity for students to learn how to conduct data analysis, examining research questions

using real data when they have no funding to gather their own [1, 3, 4, 9–14].

However, in healthcare settings, qualitative researchers often investigate sensitive or stigma-

tized issues with vulnerable participants [10, 15]. Given that qualitative data are often sensitive,

qualitative researchers have expressed concerns about informed consent, protecting confi-

dentiality, maintaining trust and relationships, and ensuring appropriate secondary uses of

data, if data were shared [1–3, 10, 16, 17]. Some argue that the information disclosed by partic-

ipants is only made possible because of the trusting relationship between researcher and partic-

ipant [1, 18, 19]. Researchers fear that sharing qualitative data could undermine this trust and

that participants may be prevented from providing full and honest disclosure if they know

data are going to be shared. In addition, participants may consent to have their data inter-

preted for one purpose, not for secondary purposes by a different researcher.

Qualitative data are non-numeric, which poses an additional de-identification challenge

because identifiers may be located anywhere within long passages of narrative text [20]. Cur-

rently, researchers must manually search for and locate identifiers within qualitative data dur-

ing data cleaning and analyses, but the process is labor intensive and we lack tools to support

researchers in this process. Adequate de-identification of qualitative data requires balancing

the protection of individual identities while ensuring adequate contextual detail remains to

enable secondary use. In concurrent work, we are developing automated support software to

assist researchers in the de-identification process [21].

Data repositories can also help address researcher concerns about QDS. Repositories store,

preserve, and manage data in a manner that enables data sharing, discovery, and citation [3,

22, 23]. Repositories are staffed with experts who can help with data curation, provide guid-

ance on preparing data for deposit, and work with researchers to determine an appropriate

level of restriction for their data, including restricted access and delayed access options for sec-

ondary users [24]. Secondary users of sensitive data typically sign a data use agreement, which

stipulates that they will not attempt to identify participants and they must obtain Institutional

Review Board (IRB) approval prior to receiving data [25]. The data use agreement is brokered

by the repository.

When adopting a new and controversial practice, it is important to engage stakeholders to

understand the facilitators and barriers to uptake, and to promote stakeholder buy-in for the

new practice [26, 27]. In this article, we report findings from a survey of qualitative researchers

regarding their experience and attitudes toward sharing health related or sensitive qualitative

data in a repository where other researchers could access data. Qualitative data are gathered in

diverse fields, including public health, social work, anthropology, medicine, occupational and

physical therapy, nursing, bioethics, psychology, and clinical research [28]. Hence, we

recruited broadly across health-related fields to ensure broad representation from qualitative

researchers. We aimed to identify researchers’ top concerns, and factors that might increase

their willingness to share.

PLOS ONE

Attitudes towards qualitative data sharing

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261719 December 31, 2021 2 / 13

data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or

preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared

that no competing interests exist.

The survey is part of a larger project to identify and overcome practical and ethical barriers

to QDS in the U.S. (R01HG009351-01A1). In the next phase of our research, we will conduct a

formative evaluation trial with 30 qualitative researchers that involves using our newly devel-

oped de-identification support software and guidelines prior to depositing their qualitative

research data set with our partner repository, the Inter-university Consortium for Political and

Social Research (ICPSR) at the University of Michigan. All survey participants were invited to

take part in the formative evaluation QDS pilot at the end of the survey. The survey aimed to

answer four research questions:

RQ #1: How supportive are qualitative researchers of sharing qualitative data with a

repository?

RQ #2: What exploratory variables are associated with overall attitudes toward qualitative data

sharing?

RQ #3: What are the most common concerns that qualitative researchers have about sharing

their qualitative data with a repository?

RQ#4: What are the most common considerations and resources that would make qualitative

researchers more willing to share their qualitative data with a repository?

Materials and methods

Survey development

Prior to survey development, formative in-depth interviews were conducted with 30 qualita-

tive researchers to inform survey content [2]. During these interviews, researchers were asked

about the practical and ethical barriers and facilitators of sharing qualitative data with a reposi-

tory. Transcripts from these interviews were coded for perceived barriers and concerns, as well

as perceived benefits and facilitators of sharing qualitative data. Interviewees expressed a wide

range of concerns and identified several benefits of sharing qualitative data with a repository.

These data and prior literature on QDS guided the development of the survey items [1, 14, 19,

29–31].

Recruitment

This study used a non-probability, criterion-based sampling approach. A non-probability

approach was necessary because there is no way to identify the number nor identity of all qual-

itative researchers. Criterion-based sampling was used to target appropriate informants: Indi-

viduals who conduct qualitative research in the U.S. We restricted our focus to the U.S.

because regulations, oversight policies, and data sharing practices might all affect attitudes,

and these vary across nations.

Qualitative researchers were contacted via email through a range of recruitment mediums.

We identified publicly available contact information of investigators through NIH RePORTER

by using the search terms ‘qualitative,’ ‘interview,’ and ‘focus group.’ We also searched aca-

demic institution websites and recruited through the listservs of professional organizations for

qualitative researchers in general (e.g., Society for Medical Anthropology). To ensure adequate

representation from minority groups, we recruited through professional organizations for

researchers from minority communities (e.g., Robert Wood Johnson Foundation New Con-

nections Network, Brothers of the Academy, Sisters of the Academy, Latina Researchers Net-

work) [32]. We also used a word of mouth approach, in which we contacted colleagues

through our professional networks to request they send the recruitment email to potential

qualitative researchers.

PLOS ONE

Attitudes towards qualitative data sharing

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261719 December 31, 2021 3 / 13

An email was distributed to qualitative researchers with a request to take the survey via an

anonymous survey link. We asked professional organizations and academic institutions to

send the link through their listservs and post the study information and anonymous survey

link on their social media accounts (e.g., Twitter or Facebook). The survey was administered

using Qualtrics survey software, which is password and firewall protected. The research was

approved as exempt by the Institutional Review Board at Washington University

(IRB#201811123). Participants who completed the survey were entered into a raffle to win one

of ten cash prizes worth $100 for participating.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using Stata statistical software (version 16.0); statistical significance is

assessed as p<0.05. Bivariate analyses were conducted using Pearson’s chi-squared test to

explore which demographic variables are associated with overall attitudes toward QDS within

this sample.

Results

Sample

Of the 676 respondents who initiated the web-based survey, 251 were excluded from

analyses for not meeting study criteria (i.e., participants had not led and conducted

qualitative research with human subjects, participants did not work at an institution in the

U.S.) or did not complete more than 50% of the survey, which was forced-choice to avoid

the problem of missing data. The final sample comprised of 425 qualitative researchers in

the U.S. from a variety of academic disciplines including: public health, bioethics, and clini-

cal fields (i.e., medicine, nursing, occupational and physical therapy) (n = 152, 38%);

anthropology and sociology (n = 133, 33%); and other disciplines (n = 118, 29%). Table 1

presents the demographic information describing the sample. The majority of participants

were female (n = 324, 76%), White (n = 242, 57%), and between 30–49 years old (n = 260,

61%).

Most qualitative researchers indicated they had been conducting qualitative research for

more than 10 years (n = 235, 55%) and collect health information (n = 301, 71%) and other

sensitive information (n = 206, 48%) in their qualitative research. Participants reported con-

ducting research with various populations, including pregnant women (n = 85, 20%), children

(n = 130, 31%), prisoners (n = 13, 3%), sexual minorities (n = 101, 24%), individuals with cog-

nitive impairments (n = 47, 11%), those older than 65 (n = 144, 34%), patients (n = 203, 48%),

racial and ethnic minorities (n = 333, 78%), economically disadvantaged people (n = 286,

67%), and individuals with sensitive diagnoses (n = 135, 32%). A variety of qualitative methods

were used by respondents, the most common being interviews (n = 415, 98%) and focus

groups (n = 321, 76%). Their work has been funded by government agencies (n = 276, 65%),

private foundations (n = 202, 48%), corporations (n = 22, 5%), and investigator’s institutions

(n = 314, 74%).

Experience and overall attitudes toward qualitative data sharing

The vast majority of researchers (n = 410, 96%) have never shared qualitative data in a reposi-

tory. Qualitative researchers were asked to rate on a seven-point Likert scale the extent to

which they oppose or support sharing qualitative research data (1 = strongly oppose,

7 = strongly support). Attitudes about sharing qualitative data were mixed. Specifically, 41%

(n = 174) of participants oppose sharing qualitative data (including strongly oppose and

PLOS ONE

Attitudes towards qualitative data sharing

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261719 December 31, 2021 4 / 13

slightly oppose), and 49% (n = 208) of participants support QDS (including strongly support

and slightly support), indicating a bimodal distribution of attitudes toward sharing qualitative

data with a repository.

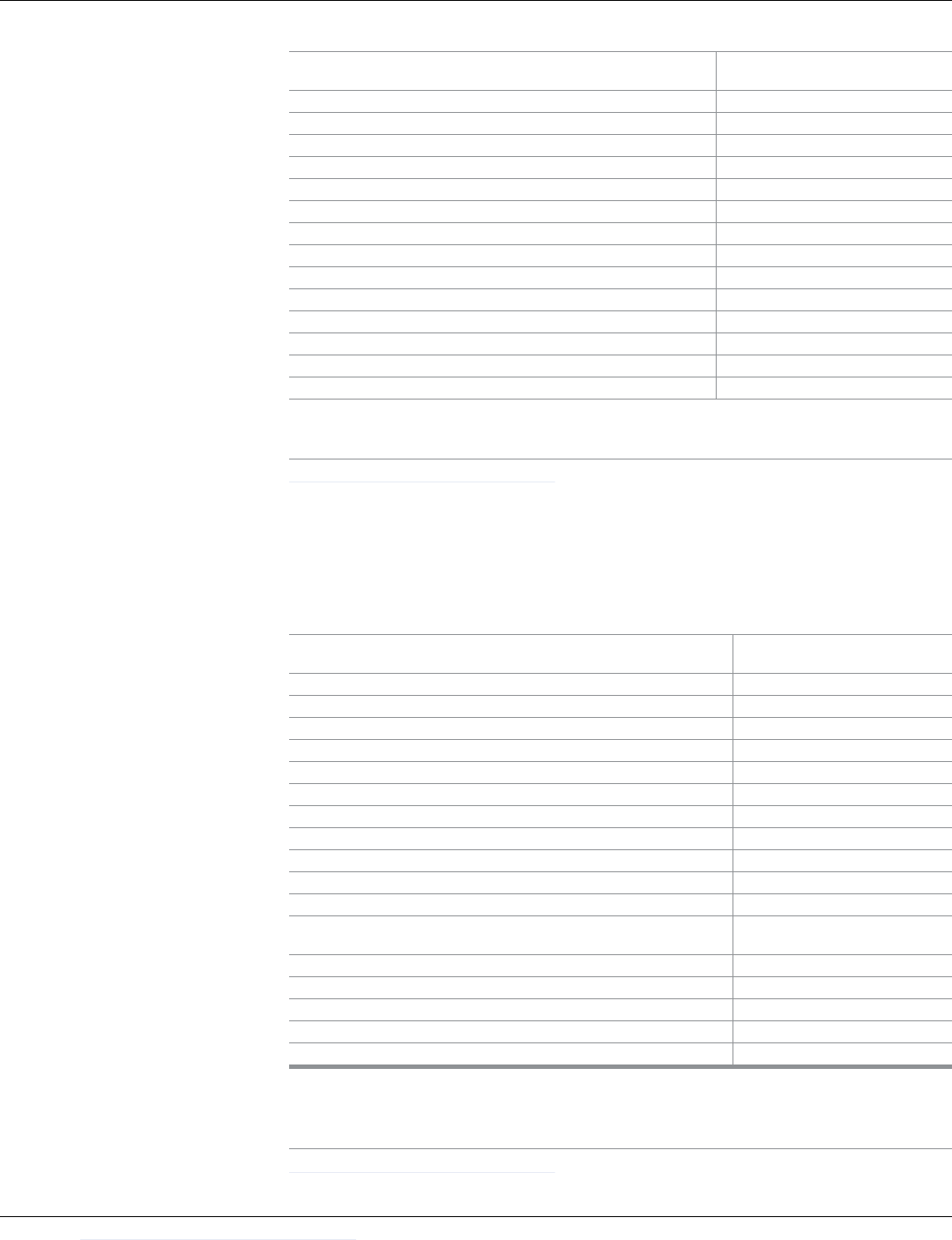

Table 1. Demographic information of survey respondents (N = 425).

Demographic Questions Percent Count

Do you ever collect both quantitative data and qualitative data in the same research project?

Yes 87% 370

No 13% 55

Do you ever gather health information in your qualitative research, such as information about a participant’s

diagnoses, symptoms, or treatments?

Yes 71% 301

No 29% 124

Do you ever gather other forms of sensitive information, such as information about illegal behaviors and sexual

behaviors?

Yes 48% 206

No 52% 219

Which of the following methods do you use to gather qualitative research data? (check all that apply)

Interviews 98% 415

Focus groups 76% 321

Observations 61% 261

Archival research 39% 165

Town hall meetings or other deliberative methods 22% 94

Other 14% 59

Who has funded your research in the last 5 years? (check all that apply)

Your institution 74% 314

Government agencies 65% 276

Private foundations 48% 202

Other 8% 35

Corporations 5% 22

Have you ever shared your qualitative research data with people outside of your research team?

No 80% 340

Yes 20% 85

Which of the following best describes how you shared your qualitative research data? (check all that apply)

�

Shared data with an individual outside of your research team 76% 65

Deposited data with a data repository or archive 18% 15

Other 18% 15

If you have shared your qualitative data, what was the reason for doing so? (check all that apply)

�

To encourage new uses for my data 59% 50

To promote new research collaborations 58% 49

To show a commitment to openness 33% 28

To increase the impact and visibility of my research findings 31% 26

Other 25% 21

A requirement of a funding agency 16% 14

A requirement of a journal 6% 5

A requirement of the institution 7% 6

To shift the burden of maintaining and archiving my data to the repository 2% 2

N = 425.

�

Question only applies to participants who have shared qualitative data previously (N = 85).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261719.t001

PLOS ONE

Attitudes towards qualitative data sharing

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261719 December 31, 2021 5 / 13

Participants’ field of study was significantly related to attitudes toward QDS, such that

those who conducted research in public health, clinical fields (e.g., nursing and medicine), and

bioethics were more likely to support sharing qualitative data (M = 4.52, SE = .16) than those

who conducted research in disciplines of anthropology or sociology (M = 3.58, SE = .17). Par-

ticipant race was significantly associated with attitudes toward QDS. Hispanic (M = 4.40, SE =

.32) and Asian (M = 4.48, SE = .39) qualitative researchers tended to be more supportive of

sharing qualitative data compared to their White (M = 4.16, SE = .13) and Black (M = 3.94, SE

= .22) qualitative researcher counterparts.

Age was associated with opposition to sharing qualitative data with a repository. Generally,

younger qualitative researchers (e.g., age 20–29, M = 4.00, SE = .38; age 30–39, M = 4.08, SE =

.16) tended to be less supportive of sharing qualitative data than qualitative researchers who

were older (e.g., age 50–59, M = 4.21, SE = .22; 60+, M = 4.39, SE = .26). Finally, participant sex

was associated with attitudes toward sharing qualitative data, such that males (M = 4.81, SE =

.21) were more supportive of sharing qualitative data than females (M = 4.04, SE = .11).

Interest in qualitative data sharing pilot study

All survey participants were asked if they were interested in participating in our pilot study

that involves using newly created de-identification support software on a qualitative data set

prior to deposit in a data repository. Here, we treat interest in participating in the pilot as a

measure of researcher willingness to share qualitative data. Out of 425 qualitative researchers,

134 (32%) expressed interest in participating in the pilot. Bivariate analyses indicate that col-

lecting sensitive qualitative data (p = 0.046), the sex of the researcher (p = 0.006), and prior

sharing experience (p = 0.019) are significantly associated with interest in participating in the

pilot. Of those researchers who gather sensitive information (n = 206), 36% (n = 74) expressed

interest in the pilot compared to 27% (n = 60) of those who do not gather sensitive information

(n = 219). Men (n = 33, 45%) were more likely to express interest in participating in the pilot

study compared to women (n = 98, 30%). Participants who reported sharing qualitative

research data with people outside of their research team in the past (n = 85) were more likely

to be interested in participating in the pilot study (n = 36, 42%) compared to those who have

not shared data previously (n = 98, 29%).

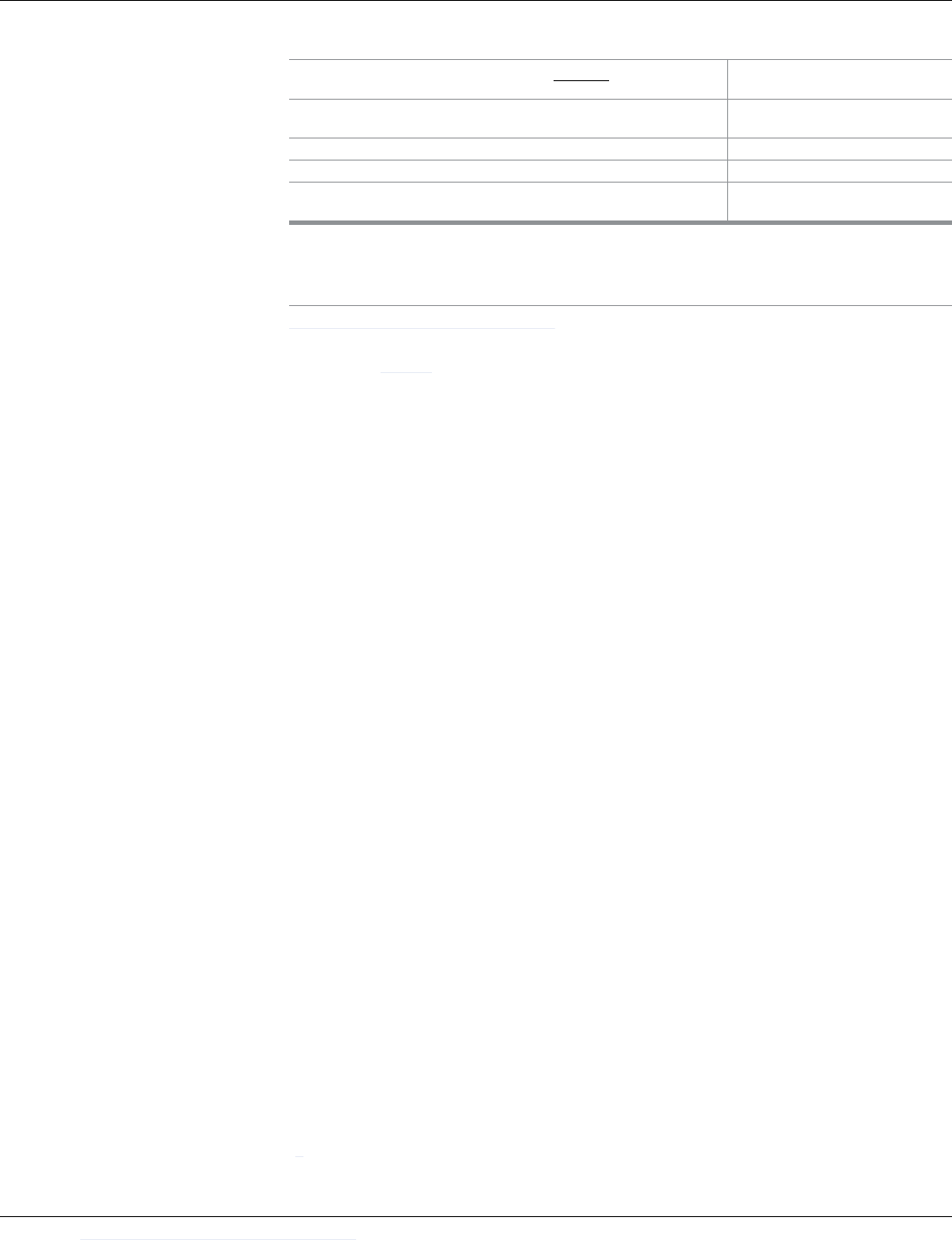

Concerns regarding qualitative data sharing

Qualitative researchers were asked how concerned they were about various factors related to

sharing their qualitative data through a repository, on a scale of 1 (not at all concerned) to 5

(extremely concerned). Table 2 presents the frequencies of these concerns. Researchers’ great-

est concerns (rated item a 3 or above) included that they lack participant permission (n = 370,

87%), data sensitivity (360, 85%), concerns about breaching participant trust (n = 349, 82%),

IRB or institutional policies (n = 336, 79%), and inability to adequately de-identify data

(n = 334, 79%).

Facilitators to qualitative data sharing

Participants were asked how likely certain considerations would increase their willingness to

share qualitative data through a repository, on a scale of 1 (not at all likely) to 5 (very likely).

Table 3 presents the frequencies of these considerations (rated item a 4 or above). Researchers

indicated that they would be most likely to share their qualitative data if doing so increased the

societal impact of their research (n = 353, 83%), if participants agreed to have their data shared

(n = 339, 80%), and if sharing led to increased future collaborations (n = 322, 76%).

PLOS ONE

Attitudes towards qualitative data sharing

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261719 December 31, 2021 6 / 13

Resources to facilitate qualitative data sharing

Qualitative Researchers were asked to rate, on a scale of 1 (not at all) to 5 (a great deal), how

much certain resources would increase their willingness to share their qualitative data through

Table 2. Concerns regarding qualitative data sharing.

How concerned are you about the following factors related to the idea

of sharing qualitative data through a repository?

Frequency of Participants Who

Indicated Concern (%)

Lack of permission from research participants to share data. 370 (87%)

The sensitivity of research data. 360 (85%)

Breach of trust with participants. 349 (82%)

IRB or institutional policies. 336 (79%)

Concern that data cannot be adequately anonymized. 334 (79%)

Losing control over who has access to my qualitative data. 326 (77%)

The time and effort to prepare data for deposit. 325 (76%)

The potential for misinterpretation of my data by other researchers. 316 (74%)

Financial cost to prepare qualitative data for deposit. 283 (67%)

Issues with legal permissions 252 (59%)

Potential for repository technology failure. 233 (55%)

My lack of knowledge about repositories and data sharing in general. 223 (52%)

Others do not deserve to use data I collected. 94 (22%)

I do not like the idea of others judging my work. 74 (17%)

Items were rated on a scale of 1 (not at all concerned), 2 (slightly concerned), 3 (moderately concerned), 4 (very

concerned), or 5 (extremely concerned). Participants were considered to be concerned if they rated 3–5.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261719.t002

Table 3. Considerations that would increase willingness to share.

How likely would each of the following considerations increase your

willingness to share qualitative data through a repository?

Frequency of Participants Willing

to Share (%)

If sharing increased the societal impact of research. 353 (83%)

If I knew my participants would agree to data sharing. 339 (80%)

If sharing led to increased collaborations. 322 (76%)

If sharing decreased the burden on participant communities. 308 (72%)

If secondary data users needed to cite their data sources in all publications. 294 (69%)

If data could be reused to explore new research questions. 283 (67%)

If sharing made data from publicly-funded research more widely available. 286 (67%)

If repositories provided a secure infrastructure for data storage. 279 (66%)

If those who share data are invited to be co-authors on papers that use data. 275 (65%)

If funding agencies required data to be shared. 266 (63%)

If sharing helped avoid duplication of work. 260 (61%)

If sharing data created the opportunity for students to learn how to analyze

data.

257 (60%)

If sharing allowed for verification of data interpretation. 230 (54%)

If sharing positively influenced career promotion decisions. 226 (53%)

If repositories provided a central catalog of available data sets. 214 (50%)

If sharing led to increased citations. 205 (48%)

If journals required data to be shared. 201 (47%)

The degree to which each consideration would increase willingness to share qualitative data were rated on a scale of 1

(not at all likely), 2 (somewhat unlikely), 3 (neutral), 4 (somewhat likely), or 5 (very likely). Participants were

considered willing to share if they rated 4 or 5.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261719.t003

PLOS ONE

Attitudes towards qualitative data sharing

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261719 December 31, 2021 7 / 13

a repository. Table 4 presents the frequencies of these resources (rated item a 4 or above). Par-

ticipants indicated that they would be more willing to share their data if repository costs were

covered by funding agencies (n = 294, 69%), if they received clear guidance on ethics and com-

pliance-related issues (n = 259, 61%), if repositories assisted with data anonymization

(n = 243, 57%), and if repositories provided consultations on sharing qualitative data (n = 207,

49%).

Discussion

Findings from the current study indicate that QDS in the U.S. remains rare, with only 4% of

qualitative researchers having ever shared qualitative data in a repository. While nearly half of

researchers expressed support for QDS, most researchers are not actually sharing qualitative

data currently. These findings, although focused on qualitative researchers in the U.S., have

implications for qualitative researchers more broadly given the international shift towards data

sharing and open science, including qualitative data, which has historically not been shared.

Limitations

We used a criterion-based sampling approach which limits the generalizability of our findings.

This non-probability approach was necessary because there is no way to identify all qualitative

researchers, so our approach was to target appropriate informants. When individuals com-

pleted the entire survey, we had no missing data from them because we used forced choice;

however, some individuals chose not to complete the survey after establishing eligibility. We

do not know how those who completed the survey differ from non-responders. In addition,

we restricted data collection to US qualitative researchers so our findings may not generalize

to other national contexts with different legal and regulatory frameworks. Finally, we con-

ducted analyses on the association of demographics (e.g., age, sex, and field of study) with atti-

tudes toward data sharing and willingness to participate in our data sharing pilot project.

These associations are “within sample” associations and should be interpreted as such.

Resources and guidance needed

Clear and transparent consent forms. Researchers’ top concerns related to obtaining

informed consent, ensuring participants agreed, and not breaching trust. Notably, in concur-

rent work, we conducted qualitative interviews with 30 qualitative research participants and

found the majority supported QDS and some assumed data sharing was already happening

[8]. Participants were broadly supportive of QDS so long as confidentiality was maintained

Table 4. Resources to facilitate data sharing.

How much would each of the following resources increase your

willingness to share qualitative data?

Frequency of Participants Willing to

Share (%)

If funding agencies would cover the cost of sharing qualitative data with a

repository.

294 (69%)

If you were given clear guidance on ethics and compliance-related issues. 259 (61%)

If a data repository assisted with data anonymization. 243 (57%)

If a data repository provided consultations regarding sharing qualitative

data.

207 (49%)

The degree to which each resource would increase willingness to share qualitative data were rated on a scale of 1 (not

at all), 2 (a little), 3 (a moderate amount), 4 (a lot) or 5 (a great deal). Participants were considered willing to share if

they rated a 4 or 5.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261719.t004

PLOS ONE

Attitudes towards qualitative data sharing

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261719 December 31, 2021 8 / 13

and data were shared with other researchers. Going forward, qualitative researchers must

ensure clear and transparent informed consent that communicates data sharing plans at the

outset of a study as this could significantly facilitate QDS, and be acceptable to participants.

Historically, qualitative researchers often promise in informed consent documents to destroy

data when the research ends or that no one outside the research team will ever access data.

These statements prohibit data sharing from the outset. While such statements may be appro-

priate in some cases where data are too sensitive to share or cannot be de-identified adequately,

in many cases clear and transparent consent forms that obtain permission for data sharing will

enable QDS going forward. We believe it is appropriate for consent forms to specifically dis-

close that secondary analyses may explore new research questions [33]. Importantly, such

broad statements would pertain to secondary analyses conducted by third parties on shared

data as well as analyses on new research questions conducted by the original investigators,

which is the most common form of “secondary analyses” currently [33].

In addition, consent forms will need to specifically disclose that secondary analyses may be

conducted once data is shared, and that such analyses may explore new or different research

questions than originally planned [33]. A recent review of qualitative secondary analyses

found that the majority were conducted by the original investigators involved in the parent

study, primarily to explore new questions on a subset of existing data, and there was a lack of

clarity when reporting on whether these analyses were an extension of the primary analyses or

a secondary analyses [33]. Informed consent documents need to include a clearer differentia-

tion of primary and secondary analyses, including that secondary analyses could explore topics

entirely unrelated to the primary study [33].

Repositories. Qualitative researchers expressed concerns regarding losing control of who

accesses data (77%), financial costs of preparing data (67%), concerns about potential reposi-

tory technological failures (55%), and lack of knowledge of repositories and QDS in general

(52%). At the same time, 66% of researchers indicated they would be more willing to share if

repositories provided a secure infrastructure for data storage. We encourage researchers to

explore available repositories, whether institutional or national, as appropriate repositories can

provide the necessary tools and guidance to facilitate QDS such as archiving data securely (and

in perpetuity) and restricting secondary users’ access to data. Restricted access, rather than

public access, is likely appropriate for most types of sensitive qualitative health data. In the U.

S., funders such as the NIH allow data sharing costs to be included in budgets, and researchers

should confirm with their funders as QDS may be an allowable cost [5].

Assistance with de-identification. The majority of qualitative researchers (79%)

expressed concerns that qualitative data cannot be adequately de-identified, and 59% reported

that resources to assist with de-identification would enhance their willingness for QDS. Cur-

rently researchers must manually sift through data to look for and remove potential identifiers,

which is labor intensive. In addition, there are no standards specific to qualitative data to

determine when it is adequately de-identified. In concurrent work, we are developing auto-

mated software to assist qualitative researchers de-identifying qualitative data [21]. Such auto-

mated tools will facilitate de-identification prior to data sharing, although researcher input is

still required to verify that data are adequately de-identified. It is also essential that data retain

adequate contextual details to enable secondary users to interpret the data. Repositories can

provide guidance on the necessary accompanying documentation and contextual data to

enable secondary use.

Factors associated with willingness to share: An area for future research. Our data indi-

cate that public health, clinical health, and bioethics researchers are more open to QDS than

researchers from other fields such as anthropology and sociology. This may be partially due to

the common use in anthropology and sociology of ethnographic methods such as participant

PLOS ONE

Attitudes towards qualitative data sharing

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261719 December 31, 2021 9 / 13

observation that require detailed, and often deeply personal, field notes. These data may be

especially difficult to de-identify and present greater challenges for sharing than a one-time

qualitative interview conducted in a public health or medical research setting. Alternately, this

may reflect the cultures in which public health, medical, and nursing researchers work and

their funding sources [9]. In contrast to researchers in disciplines like anthropology who may

return to field notes throughout their careers for analyses, researchers in medicine, nursing,

and public health are more likely to conduct contract funded research with a clear end date [9]

and funders may also require data sharing. These qualitative researchers often have data that

may not have been ‘fully mined’ by the time research funding ends, creating opportunities for

further analyses [9]. Biomedical and public health researchers may be prime candidates for

championing and helping to normalize QDS.

Qualitative researchers’ age, sex, and race were associated with attitudes toward QDS in our

sample, with men, those who are older in age, and Asians and Hispanics being more support-

ive of QDS compared to their counterparts. Given that our survey was not designed to deter-

mine why these factors are associated with attitudes towards sharing, future research is needed

to better understand whether, how, and why individual factors may influence willingness to

share. Future research should also examine what resources could help overcome barriers to

sharing qualitative data with a repository outside of the U.S., as barriers will likely differ by

national context.

QDS is feasible and can improve healthcare

Qualitative data are often sensitive, provide rich information, and seek to explore complex

inquiries not adequately addressed using quantitative methods. Qualitative insights have

changed healthcare and practice, suggesting there is much unrealized potential if more qualita-

tive data were shared. For instance, a systematic review of 77 original qualitative studies on a

form of chronic pain led to a new understanding of pain as an ‘adversarial struggle’, illustrating

that a central component of therapy is that patients must feel recognized and heard by physi-

cians [13]. At the same time, the existence of nearly 80 studies on a similar topic suggests that

qualitative research may at times be wasteful or duplicative; an avoidable occurrence if qualita-

tive data were shared more broadly [11].

QDS has the potential to improve transparency, promote secondary data analysis, and facili-

tate research training, but researcher attitudes and behaviors need to change. In fact, researchers

cited increasing the societal impact of their work and future collaborations as key factors that

would increase their willingness to share. Realizing such goals will require actually changing

behavior and long-held attitudes about QDS. The UK illustrates this potential for change. There

has been a slow but steady rise in qualitative data sharing as a result of the open data movement,

funding policies, changing attitudes, and the availability of practical procedures and ‘mature

infrastructure’ through the UK Data Archive [3]. An analysis of 267 data sets in the UK Data

Archive (not necessarily health related) indicates there were 7,155 unique downloads of these

data sets. Data were primarily used for learning (64%), research (15%), and teaching (13%) and

demonstrate the ‘scale and significance of the reuse of data for teaching and learning’[3].

Our current project aims to provide the necessary support and resources to facilitate QDS

in the U.S., including developing a software to support the de-identification of qualitative data,

and a QDS Toolkit containing guidance and materials. We are engaging diverse stakeholders

to identify concerns and needs, develop and evaluate the Toolkit, and will disseminate the

Toolkit to strategic groups while evaluating its adoption. At the end of the project, the Toolkit

—including the software—will be made available to support data sharing in an ethical manner

in the U.S.

PLOS ONE

Attitudes towards qualitative data sharing

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261719 December 31, 2021 10 / 13

The NIH is moving ‘toward a future in which data sharing is a community norm’[5],

including sharing de-identified qualitative health data, and other funding agencies may soon

follow suit. It is imperative that qualitative researchers increase their knowledge of how to

share their qualitative research data responsibly. Widespread, responsible sharing of qualitative

data can have a lasting positive impact on health knowledge and interventions [9, 11–13, 34,

35]. Systematic guidelines and support for responsible and ethical QDS are needed to realize

the potential benefits while protecting confidentiality and maintaining trust among research

participants and the research community. Some data, if released and not shared responsibly,

could present real harm to participants. However, responsible sharing of qualitative health

data is possible and would maximize the value and use of data for health, social science, and

policymaking.

Supporting information

S1 Data.

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all participants who completed the survey and Ruby Varghese for her assis-

tance with data collection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: James M. DuBois.

Data curation: Jessica Mozersky, Tristan McIntosh, Heidi A. Walsh, Meredith V. Parsons,

James M. DuBois.

Formal analysis: Jessica Mozersky, Tristan McIntosh, Melody Goodman, James M. DuBois.

Funding acquisition: James M. DuBois.

Methodology: Melody Goodman.

Project administration: Heidi A. Walsh, Meredith V. Parsons.

Supervision: James M. DuBois.

Writing – original draft: Jessica Mozersky, Tristan McIntosh.

Writing – review & editing: Jessica Mozersky, Tristan McIntosh, Heidi A. Walsh, Meredith

V. Parsons, Melody Goodman, James M. DuBois.

References

1. DuBois JM, Strait M, Walsh H. Is It Time to Share Qualitative Research Data? Qualitative Psychology.

2018; 5(3):380–93. Epub 2019/01/22. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000076 PMID: 30662922; PubMed

Central PMCID: PMC6338425.

2. Mozersky J, Walsh H, Parsons M, McIntosh T, Baldwin K, DuBois JM. Are we ready to share qualitative

research data? Knowledge and preparedness among qualitative researchers, IRB members, and data

repository curators. IASSIST Quarterly. 2020; 43(4):1–23. https://doi.org/10.29173/iq952 PMID:

32205903

3. Bishop L, Kuula-Luumi A. Revisiting Qualitative Data Reuse. SAGE Open. 2017; 7(1). https://doi.org/

10.1177/2158244016685136

4. Corti L, Fielding N, Bishop L. Editorial for Special Edition, Digital Representations. SAGE Open. 2016; 6

(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016679211 PMID: 31131152

PLOS ONE

Attitudes towards qualitative data sharing

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261719 December 31, 2021 11 / 13

5. National Institutes of Health. NIH Data Sharing Policy and Implementation Guidance Bethesda, Mary-

land: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2020 [updated October 29, 2020; cited 2020

Nov 6]. Available from: https://grants.nih.gov/grants/policy/data_sharing/data_sharing_guidance.htm.

6. Nosek BA, Alter G, Banks GC, Borsboom D, Bowman SD, Breckler SJ, et al. SCIENTIFIC STAN-

DARDS. Promoting an open research culture. Science. 2015; 348(6242):1422–5. Epub 2015/06/27.

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aab2374 PMID: 26113702; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4550299.

7. Nosek BA. Estimating the Reproducibility of Psychological Science. Science. 2015; 349(6251). https://

doi.org/10.1126/science.aac4716 PMID: 26315443

8. Mozersky J, Parsons M, Walsh H, Baldwin K, McIntosh T, DuBois JM. Research Participant Views

regarding Qualitative Data Sharing. Ethics & human research. 2020; 42(2):13–27. https://doi.org/10.

1002/eahr.500044 PMID: 32233117

9. Barbour RS. The role of qualitative research in broadening the ‘evidence base’ for clinical practice. Jour-

nal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2000; 6(2):155–63. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2753.2000.

00213.x PMID: 10970009

10. Broom A, Cheshire L, Emmison M. Qualitative Researchers’ Understandings of their Practice and the

Implications for Data Archiving and Sharing. Sociology. 2009; 43(6):1163–80.

11. Corti LT P. Secondary analysis of archived data. In: Seale CG G.; Gubrium J. F.; Silverman D., editor.

Qualitative research practice: Sage Publications Ltd; 2004. p. 297–313.

12. Grypdonck MH. Qualitative health research in the era of evidence-based practice. Qual Health Res.

2006; 16(10):1371–85. Epub 2006/11/03. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732306294089 PMID:

17079799.

13. Toye F, Seers K, Allcock N, Briggs M, Carr E, Andrews J, et al. A meta-ethnography of patients’ experi-

ence of chronic non-malignant musculoskeletal pain. Health Serv Deliv Res. 2013; 1(12). https://doi.

org/10.3310/hsdr01120 PMID: 25642538

14. Yardley SJ, Watts KM, Pearson J, Richardson JC. Ethical issues in the reuse of qualitative data: per-

spectives from literature, practice, and participants. Qual Health Res. 2014; 24(1):102–13. Epub 2014/

01/01. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732313518373 PMID: 24374332.

15. Power R. The Role of Qualitative Research in HIV/AIDS. AIDS. 1998; 12(7):687–95. https://doi.org/10.

1097/00002030-199807000-00004 PMID: 9619799

16. Hammersley M. Can We Re-Use Qualitative Data Via Secondary Analysis? Notes on Some Termino-

logical and Substantive Issues. Sociological Research Online. 2010; 15. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.

2076

17. Walters P. Qualitative archiving: engaging with epistemological misgivings. Aust J Soc Issues. 2009; 44

(3):309–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1839-4655.2009.tb00148.x WOS:000208409000005.

18. Guishard MA. Now’s not the time! Qualitative data repositories on tricky ground. Comment on DuBois

et al. (2017). Qualitative Psychology. 2017. Epub Mar 16. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/qup0000085.

19. Tsai AC, Kohrt BA, Matthews LT, Betancourt TS, Lee JK, Papachristos AV, et al. Promises and pitfalls

of data sharing in qualitative research. Social Science & Medicine. 2016; 169:191–8. Epub 2016/10/23.

PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5491836. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.08.004 PMID:

27535900

20. Greener I. Designing social research: A guide for the bewildered. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2011.

21. Gupta A, Lai A, Mozersky J, Ma X, Walsh H, DuBois JM. Enabling qualitative research data sharing

using a natural language processing pipeline for deidentification: moving beyond HIPAA Safe Harbor

identifiers. JAMIA Open. 2021; 4(3):ooab069. Epub 2021/08/27. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamiaopen/

ooab069 PMID: 34435175; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8382275.

22. Corti L, Van den Eynden V. Learning to manage and share data: jump-starting the research methods

curriculum. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2015; 18(5):545–59. https://doi.org/

10.1080/13645579.2015.1062627

23. Mannheimer S, Pienta A, Kirilova D, Elman C, Wutich A. Qualitative Data Sharing: Data Repositories

and Academic Libraries as Key Partners in Addressing Challenges. American Behavioral Scientist.

2019; 63(5):643–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764218784991 PMID: 31693016

24. ICPSR, Institute for Social Research University of Michigan. Guide to Social Science Data Preparation

and Archiving: Best Practice Throughout the Data Life Cycle. Ann Arbor, MI: 2012 978-0-89138-800-5.

25. National Institutes of Health. NIH Data Sharing Policy and Implementation Guidance 2003 [updated

February 9, 2012; cited 2020 June 29]. Available from: http://grants.nih.gov/grants/policy/data_sharing/

data_sharing_guidance.htm#funds.

26. Brownson RC, Colditz GA, Proctor EK. Dissemination and implementation research in health: translat-

ing science to practice. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. xxiii, 536 p. p.

PLOS ONE

Attitudes towards qualitative data sharing

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261719 December 31, 2021 12 / 13

27. Dubois JM, Bailey-Burch B, Bustillos D, Campbell J, Cottler L, Fisher CB, et al. Ethical issues in mental

health research: the case for community engagement. Current opinion in psychiatry. 2011; 24(3):208–

14. Epub 2011/04/05. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283459422 PMID: 21460643; PubMed

Central PMCID: PMC3528105.

28. Gibson G, Timlin A, Curran S, Wattis J. The Scope for Qualitative Methods in Research and Clinical Tri-

als in Dementia. Age and ageing. 2004; 33(4):422–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afh136 PMID:

15226116.

29. Corti L, Van den Eynden V, Bishop L, Woollard M. Managing and Sharing Research Data: A Guide to

Good Practice. Metzler K, editor. London, UK: SAGE Publications Inc.; 2014 March 31, 2014.

30. Kuula A. Methodological and ethical dilemmas of archiving qualitative data. Iassist Quarterly. 2010/

2011; 34/35(3–4/1–2):12–7.

31. Yoon A. “Making a Square Fit into a Circle”: Researchers’ Experiences Reusing Qualitative Data. Pro-

ceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology. 2014; 51(1):1–4. https://doi.

org/10.1002/meet.2014.14505101140

32. Scharff DP, Mathews KJ, Jackson P, Hoffsuemmer J, Martin E, Edwards D. More than Tuskegee:

Understanding Mistrust about Research Participation. Journal of health care for the poor and under-

served. 2010; 21(3):879–97. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.0.0323 PMID: 20693733

33. Ruggiano N, Perry TE. Conducting secondary analysis of qualitative data: Should we, can we, and

how? Qualitative Social Work. 2019; 18(1):81–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325017700701 PMID:

30906228.

34. Conrad P. The meaning of medications: Another look at compliance. Social Science & Medicine. 1985;

20(1):29–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(85)90308-9.

35. Walsh D, Downe S. Meta-Synthesis Method for Qualitative Research: A Literature Review. Journal of

advanced nursing. 2005; 50(2):204–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03380.x PMID:

15788085

PLOS ONE

Attitudes towards qualitative data sharing

PLOS ONE | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261719 December 31, 2021 13 / 13