UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (http

s

://dare.uva.nl)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

Exclusion as urban policy: The Dutch 'Act on Extraordinary Measures for Urban

Problems'

van Gent, W.; Hochstenbach, C.; Uitermark, J.

DOI

10.1177/0042098017717214

Publication date

2018

Document Version

Final published version

Published in

Urban Studies

License

CC BY-NC

Link to publication

Citation for published version (APA):

van Gent, W., Hochstenbach, C., & Uitermark, J. (2018). Exclusion as urban policy: The

Dutch 'Act on Extraordinary Measures for Urban Problems'.

Urban Studies

,

55

(11), 2337-

2353 . https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017717214

General rights

It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s)

and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open

content license (like Creative Commons).

Disclaimer/Complaints regulations

If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please

let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material

inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter

to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You

will be contacted as soon as possible.

Download date:27 Aug 2024

Policy review

Urban Studies

2018, Vol. 55(11) 2337–2353

Ó Urban Studies Journal Limited 2017

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0042098017717214

journals.sagepub.com/home/usj

Exclusion as urban policy: The

Dutch ‘Act on Extraordinary

Measures for Urban Problems’

Wouter van Gent

University of Amsterdam, Netherlands

Cody Hochstenbach

University of Amsterdam, Netherlands

Justus Uitermark

University of Amsterdam, Netherlands

Abstract

The Dutch government introduced the Act on Extraordinary Measures for Urban Problems in 2006 to

bolster local regeneration efforts. The act enables local governments to stop specific groups of deprived

households from moving into designated neighbourhoods. More specifically, the Act allows local govern-

ments to refuse a residence permit to persons who ha ve lived in the metropolitan region for less than

six years and who do not receive an income from work,pensionsorstudentloans. The policy is based

on the idea that reducing the influx of poor newcomers improves liveability by providing a temporary

relief of the demand for public services and by making neighbourhoods demographically ‘balanced’ or

‘socially mixed’. This review examines the socio-spatial effects of the Act in Rotterdam between 2006

and 2013. While the Act produces socio-demographic changes, the state of the living envir onment in des-

ignated areas seems to be worsening rather than improving. Our findings show that the policy restricts

the rights of excluded groups without demonstrably impro ving safety or liveability. The revie w concludes

with a reflection on how the Act may signify a broader change in European statecraft and urban policy .

Keywords

exclusion, housing, social mixing, socio-spatial analysis, urban policy

᪈㾱

㦧ޠ᭯ᓌ൘ 2006 ᒤࠪਠҶljᐲ䰞仈䶎ᑨ᧚ᯭ⌅ṸNJԕ᧘ࣘൠᯩ⭏ᐕDŽ䈕⌅Ṹ֯ᗇൠᯩ

᭯ᓌਟԕ䱫→⢩ᇊⲴ䍛ഠᇦᓝ㗔փᩜޕᤷᇊⲴ㺇४DŽᴤާփ㘼䀰ˈ䈕⌅Ṹݱ䇨ൠᯩ᭯ᓌᤂ㔍ੁ

൘བྷ䜭ᐲ४ትտнࡠޝᒤⲴӪԕ৺ᵚ䙊䗷ᐕǃޫ㘱䠁ᡆᆖ⭏䍧Ⅾ㧧ᗇ᭦ޕⲴӪਁ᭮ትտ䇨ਟ

䇱DŽ䘉亩᭯ㆆสҾⲴᙍ䐟ᱟ߿ቁ䍛ഠӪਓⲴ⍱ޕ㜭Ჲᰦ㕃䀓ޜޡᴽ࣑䴰≲ˈᒦ֯ᗇ㺇४൘Ӫਓ

к“ᒣ㺑”ᡆ“ާᴹ⽮Պਸᙗ”ˈӾ㘼᭩ழᇌት〻ᓖDŽᵜ䇴䇪Ự㿶Ҷ䈕ᯩṸ 2006 㠣 2013 ᒤ䰤ሩ

咯⢩ѩ䙐ᡀⲴ⽮Պオ䰤ᖡ૽DŽ㲭❦䈕⌅ṸᑖᶕҶ⽮Պ-ӪਓⲴਈॆˈնᤷᇊ४ฏⲴ⭏⍫⧟ຳ⣦ߥ

լѾ൘ᚦॆ㘼䶎᭩ழDŽᡁԜⲴ⹄ウ㺘᰾ˈ䘉亩᭯ㆆ䲀ࡦҶ㻛ᧂ䲔㗔փⲴᵳ࡙ˈ਼ᰦ৸⋑ᴹ䇱ᦞ

㺘᰾᭩ழҶ㺇४Ⲵᆹޘᙗᡆᇌት〻ᓖDŽᵜ䇴䇪ᴰਾ৽ᙍҶ䈕⌅Ṹྲօણ⵰ᴤབྷ㤳തⲴ⅗⍢ഭ

ᇦ⋫⨶઼ᐲ᭯ㆆਈ䶙DŽ

ޣ䭞䇽

ᧂ䲔ǃտᡯǃ⽮Պਸǃ⽮Պオ䰤࠶᷀ǃᐲ᭯ㆆ

Received October 2016; accepted May 2017

This paper provides a policy review of a piece

of legislation introduced by the Dutch govern-

ment in 2006: the Act on Extraordinary

Measures for Urban Problems. The Act’s

main goal is to give municipalities more dis-

cretion to improve neighbourhoods’ liveability

by prohibiting jobless newcomers from mov-

ing into rental dwellings in areas considered

particularly vulnerable or distressed. Local

governments that apply the Act can refuse a

residence permit to persons who have lived in

the metropolitan region for less than six years

(the newcomer criterion) and who do not

receive an income from work, pensions or stu-

dent loans (the income criterion).

1

The Act

was first introduced in 2006 in four neigh-

bourhoods in Rotterdam South (Carnisse,

Hillesluis, Oud-Charlois, Tarwewijk), and in

2010 a fifth neighbourhood, Bloemhof, was

added. Although the Act has been and

remains controversial, it has since been imple-

mented more widely and for more purposes

(Ouwehand and Doff, 2013; Schinkel and

Van den Berg, 2011; Uitermark et al., 2017).

This polic y review focuses on the Act as it

was applied during the period up to 2013,

when application was limited to the above-

mentioned five neighbourhoods.

The Act raises a number of vexing ques-

tions. Some questions are political, moral

and legal: Is it legitimate to limit the rights of

already vulnerable groups in order to

improve distressed areas? Is it acceptable to

discriminate against people on the basis of

their employment situation or duration of

residence? From an ethical point of view, it

may be argued that the policy’s goals or

effects are immaterial when fundamental

rights are curtailed. Yet individual rights can

be, and often are, suspended when it serves a

greater good. Proponents have argued that

the government should opt for the most

effective policies, even if those policies violate

the rights of some groups under some condi-

tions (see Uitermark et al., 2017). This would

imply that the policies are exclusionary but

effective. In this policy review, we focus on

the question of efficacy by evaluating the

Act’s socio-spatial effects. We answer two

questions. First, what are the social charac-

teristics of those who are not eligible to live

in designated areas and how did the policy

affect their housing market position? Second,

how did the designated areas change in terms

of social composition, liveability, and safety

in the years after implementation? Our find-

ings can serve as input for broader debates

regarding the policy’s effects and the possible

trade-offs between efficacy and rights in

urban policy. From an international perspec-

tive, the Act may seem singular in its meth-

ods, but its goals relate to familiar themes in

urban policy: social mixing through area-

based initiatives. As such, it constitutes an

extreme case where individual rights have

been suspended in the interest of creating sta-

ble and integrated urban neighbourhoods.

The following section frames the Act in

terms of debates on social mixing and social

integration. After a methodological section

covering data and methods, two empirical

sections discuss the effects on excluded

groups and on areas respectively. After sum-

marising our findings, we conclude by

reflecting on the findings in view of broader

policy trends.

Social mixing policies

There is a long history of state planners

seeking to influence or alter the social com-

position of urban neighbourhoods (e.g.

Sarkissian, 1976). One motivation for social

Corresponding author:

Wouter van Gent, Department of Geography, Planning and International Development Studies, Amsterdam Institute for

Social Science Research, University of Amsterdam, Nieuwe Achtergracht 166, Amsterdam 1018 WV, Netherlands.

Email: W.P.C.vanGent@uva.nl

2338 Urban Studies 55(11)

mixing might be that deprived households

benefit if they live amidst more affluent

households. In the Western European con-

text, these arguments have not been particu-

larly convincing, given the relatively low

levels of segregation and small ‘neighbour-

hood effects’ (Galster, 2007; Miltenburg,

2017). Research suggests that poverty and

deprivation are rooted in structural inequal-

ities and that neighbourhood restructuring

does not affect the cause of marginality

(Andersson and Musterd, 2005; Sampson,

2012; Slater, 2013). Given the weak or

absent evidence base for policies countering

neighbourhood effects, some have argued

that social mixing policies in Western

Europe may also serve functions of state-

craft. Uitermark (2003) pointed to the influ-

ence of local administrators and service

providers in devising Dutch urban policies.

For these local professionals, concentrations

of marginality were experienced as an

uneven burden to shoulder. Deconcentration

and less population turnover would allow

them to provide services with lasting results

and make deprived neighbourhoods more

manageable (Uitermark, 2003; see also

Uitermark, 2014; Wacquant, 2008).

Governments can intervene into neigh-

bourhoods’ population compositions in vari-

ous ways. Housing voucher programmes,

such as Moving to Opportunity and Section

8 in the USA, allow selected poor households

to enter more affluent areas (Stone and

Stoker, 2015). Such individual-focused poli-

cies are less common compared with area-

based initiatives, that rely on renewal, new

housing development, and other interven-

tions in the built environment. Through

housing market restructuring and tenure

conversion, a new population may be accom-

modated. This change may be done by insert-

ing affordable or social rental housing in

relatively affluent areas. While this has been

done in Sweden in the past (Bergsten and

Holmqvist, 2013), the reverse – introducing

private housing in concentrations of social

housing – has been far more common.

The 1990s and 2000s saw the emergence

of holistic neighbourhood policies in a num-

ber of countries, including the French

Politique de Ville, the Swedish Metropolitan

Initiative, the English New Deal for

Communities, and the Dutch Big Cities pol-

icy (see Dikecx, 2007; Finn et al., 2007;

Parkinson, 1998; Uitermark, 2014; Van

Gent et al., 2009). Such area-based initia-

tives employ a range of measures in the

fields of housing, education and employ-

ment to upgrade neighbourhoods. These

policies are usually undergirded by attempts

to change the population composition of

deprived neighbourhoods. By selling off,

renovating, or demolishing public housing

and adding more upscale dwellings, urban

policies aim to deconcentrate stigmatised

and deprived population groups while

attracting residents with more status and

higher incomes.

2

In addition to comprehen-

sive restructuring, the state may also rely on

targeted investments in housing, transporta-

tion infrastructure and public space to

attract more affluent newcomers (Van Gent,

2010). Although the benefits for residents

have been disputed, these policies have been

praised for developing integrated and

joined-up policy approaches (Finn et al.,

2007; Musterd and Ostendorf, 2008). While

some of these policy measures are still in

effect, this type of urban policy has been los-

ing momentum in recent years. By 2012, the

UK, the USA, Sweden and the Netherlands

had by and large dissolved most national

programmes that relied on area-based initia-

tives in deprived neighbourhoods.

Social mixing redux: Act on

Extraordinary Measures for

Urban Problems

The Act on Extraordinary Measures for

Urban Problems was developed in 2002 and

van Gent et al. 2339

2003, at a time when integrationist urban

renewal policies were still fully operational.

At the time, the newly elected government of

Rotterdam – led by Leefbaar Rotterdam–

argued that the extant policies fell short.

Leefbaar Rotterdam had just emerged in

local politics with a populist agenda that

problematised the immigration of poor and

migrant groups (Uitermark and Duyvendak,

2008: 1494). In their view, the extraordinary

problems facing Rotterdam and the ineffec-

tiveness of previous efforts meant that

unconventional measures were needed. Its

main concern was that all efforts to improve

neighbourhoods would remain ineffective as

long as there was an influx of poor newco-

mers. Rotterdam’s plea for new measures

led to protracted debate in national parlia-

ment. Ultimately, national government par-

ties (Christian democrats, conservative

liberals and the liberal democrats) and sev-

eral opposition parties – including the social

democrats – agreed on national legislation

that would halt this influx: the Act on

Extraordinary Measures for Urban

Problems. The measures provided by the

Act aim to ‘actively countervail existing

income segregation in the city in the short

term, and, as such, improve the living envi-

ronment in designated areas’

3

(Tweede

Kamer, 2005: 12).

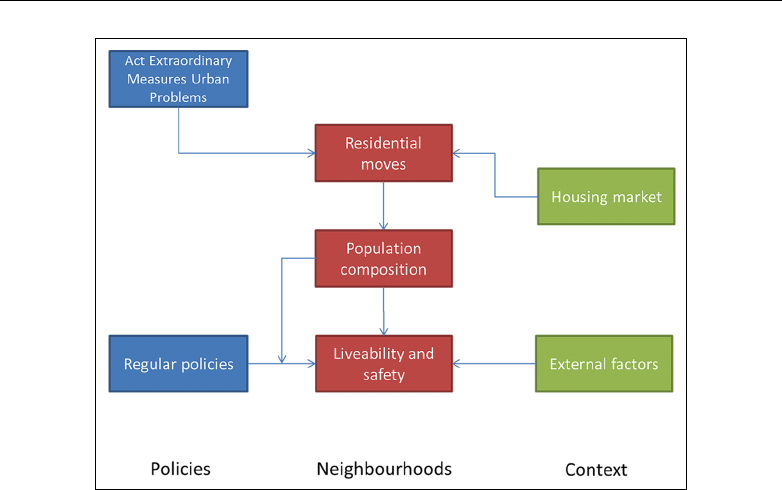

By preventing poor newcomers from

moving in, the Act aims to improve neigh-

bourhoods in two ways (see Figure 1). First,

it is anticipated that employed people will fill

up the housing vacancies that otherwise

might have been filled by jobless newcomers.

This is considered ‘necessary for a healthy

socio-economic base’ (Ministry of the

Interior and Kingdom Relations, 2014: 1),

which should in turn translate into neigh-

bourhoods that are more livable. Second,

the Act aims to increase the effectiveness of

existing policies by providing temporary

relief from the influx of poor newcomers.

Several policymakers use the Dutch proverb

‘dweilen met de kraan open’, which literally

translates as mopping while the tap is run-

ning, to emphasise that existing problems

cannot be effectively addressed until the

influx of weak households (seen as potential

problem cases) slows or stops. According to

the theory informing the policy, as soon as

administrators can focus their efforts on

resolving existing problems, it will be much

easier to improve neighbourhood liveability

(Figure 1). To fulfill this second policy aim,

municipalities therefore have to demonstrate

that they have already implemented a range

of social and neighbourhood improvement

measures before they can obtain permission

from the Minister to implement the Act.

In sum, the policy is based on the idea

that reducing the influx of poor newcomers

improves liveability through different path-

ways. While dictionaries define liveability as

the degree to which the living environment

matches the needs and expectations of its

residents, in Dutch policy practice the con-

cept refers more to the status of a neigh-

bourhood as measured by the value of its

real estate and (predicted) levels of neigh-

bourhood satisfaction (see De Wilde and

Franssen, 2016; Kaal, 2011; Uitermark

et al., 2017).

While the Act constitutes a new and argu-

ably more extreme form of urban policy –

i.e. the a priori exclusion of certain groups of

tenants – the overall goals of the Act are the

same as those of previous integrationist

urban policies. Policymakers still aim to

counteract a spiral of neighbourhood decline

by making neighbourhoods demographically

‘balanced’, by which they mean that the pro-

portion of poor and low-income households

should not be too high. The official focus is

on socio-economic change, yet the origins of

the Act are also to be found in concerns over

too much immigration and too little integra-

tion: ‘Living in a concentration area is, in

the eyes of the government, detrimental to

the integration of especially the non-native

2340 Urban Studies 55(11)

population who is low or uneducated and

non-proficient in Dutch’ (Tweede Kamer,

2005: 12). While the Act was explicitly

designed to be implemented along with

(existing) integrationist policies, more recent

developments suggest that the Act also

serves as a substitute for social mixing poli-

cies. Although there are social policy mea-

sures that target deprived neighbourhoods

in Rotterdam South, the Big Cities Policy of

the 1990s and 2000s and the housing restruc-

turing funds have been de facto dissolved.

As a result, in Rotterdam the Act has now

become an important tool to change the

social composition of the areas designated

for its implementation.

The Act may signal a broader change in

policy logic. As governments move away

from integrated programmes and costly phys-

ical interventions, they may increasingly

resort to more affordable policies that aim to

stabilise or upgrade neighbourhoods by

excluding deprived residents while attracting

more privileged residents. Although the Act

is (as far as we know) unique, there are sev-

eral other cases of governments opting to

(temporarily) exclude residents with the pur-

ported aim of protecting vulnerable estates or

neighbourhoods from decline. In Denmark in

the 1990s and early 2000s, the central govern-

ment allowed municipalities and housing

associations to control the influx of immi-

grants and marginalised groups to deprived

areas (Fridberg and Lausten, 2004; Skifter

Andersen, 2003). In Milan, municipal bylaws

to fight urban d ecay in the Padova-Trotter

area have imposed curfews on local stores

and restaurants, while enlisting property

owners to identify undocumented immigrants

(Bonfigli, 2013; see also Bricocoli and Cucca,

2016). In the USA, previously convicted

individuals may disqualify – or face large

obstacles – from obtaining public housing,

receiving housing vouchers or residing with

friends or relatives who are in public housing

(Stone and Stoker, 2015; Walter et al., 2017).

In Sweden, administrators in Landskrona

(near Malmo

¨

) are experimenting with policies

to prohibit low-income households from set-

tling in renovated rental h ousing (Baeten,

2016). While some of these have been tempo-

rary ‘emergency’ measures, or successfully

contested, they may serve as a precursor to,

or testbed for more permanent modes of sta-

tecraft (Uitermark et al., 2017). We therefore

view the willingness of governments to rely

on such measures as a shift in dealing with

urban poverty and marginalisation. We will

return to this shift from integrationist to

exclusionary policies in the conclusion, both

because it is significant in itself and because it

is important to understand the efficacy, or

lack thereof, of the Act on Extraordinary

Measures for Urban Problems.

Methods and data

This evaluation looks at the effects of the

Act on individuals who are no longer able to

move into designated areas, as well as the

development of the social situation in the

designated areas. Our study relies mostly on

quantitative methods commonly used in

population geography and residential mobi-

lity studies. In addition, we conducted 11

formal interviews with local policymakers,

civil servants, and housing association offi-

cials. We also interacted with several policy-

makers from the Ministry of the Interior and

Kingdom Relations. This qualitative data

provides us with context for the Rotterdam

case and has helped us reconstruct the the-

ory informing the policy (see Figure 1).

Our analyses focus on the characteristics

and behaviour of individuals who are ineligi-

ble for a housing permit in designated areas.

Not all of them will have wanted or tried to

move into the designated areas. Since we have

no way of knowing who would have been

interested in moving to these areas, we have

looked at the group that – on the basis of its

residential history and employment situation

van Gent et al. 2341

– would have been refused a housing permit if

ithadtried.Werefertoallpeopleinthis

group as ‘excluded r esidents’, since the Act

prohibits them from entering the areas as

tenants. Excluded residents are defined as

individuals who are part of households in

which no one meets the eligibility require-

ments. This means that no member has suffi-

cient years of residency and has no income

from work, pensions or student benefits and

is not a business owner. In addition, we define

a reference group to compare residential and

mobility behaviour. These individuals also

have no source of income from work, etc.,

but do have sufficient years of residency in

the region to be eligible. This group has a sim-

ilar socio-economic status to excluded resi-

dents but is not affected by the Act.

To study the policy’s impact on excluded

residents, we use longitudinal data sets from

the System of Social-statistical Databases

(SSD) of Statistics Netherlands. These data

sets are based on register and tax data and

have individual-level data on age, gender,

immigration status, household composition,

income, source of income, education, hous-

ing tenure characteristics, and neighbour-

hood of residence for each year. Residency

data are available from 1998, so we can

ascertain a six-year presence in the region

(one of the eligibility criteria) from 2004.

Our analyses focus on the period 2004 until

2013. As the Act was introduced in 2006, we

have data from two years before implemen-

tation to compare trends.

To gauge the social development of the

designated Rotterdam neighbourhoods, we

use additional data provided by the

Statistics Department of Rotterdam

Municipality. This includes housing market

data and the Safety Index, the latter of

which is a composite indicator consisting of

register and survey data measuring safety at

the neighbourhood level. We were able to

Figure 1. Theory informing the Act on Extraordinary Measures for Urban Problems (chapter 3, article 8).

Source: Authors’ interpretation based on Tweede Kamer (2005) and personal communication with representatives of the

Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations.

2342 Urban Studies 55(11)

use several composites related to theft, vio-

lence, burglary and drug-related nuisance as

well as data on vandalism, local nuisances

and residents’ assessments of their neigh-

bourhood’s cleanliness, repair and safety

(see Noordegraaf, 2008). Because the official

Safety Index also includes variables on pop-

ulation composition and housing stock (e.g.

ethnic minorities, unemployment and social

housing as negative predictors), we use a

modified version excluding these dimen-

sions. The definition of the neighbourhoods

follows that of Statistics Netherlands, which

was also used to designate the areas in which

to implement the Act.

Designated areas

After some experimentation, permission to

implement the Act in four neighbourhoods in

Rotterdam South was requested in 2006:

Hillesluis, Carnisse, Oud-Charlois and

Tarwewijk. Based on unemployment rates,

housing market structure and a prognosis of

an increase in non-native population, the

expectation was that problems of a social,

economic and physical nature would accu-

mulate beyond control, and therefore appli-

cation of the Act was deemed necessary.

Bloemhof was added in 2010 based on multi-

ple composite ‘liveability’ indicators. The fol-

lowing evaluation covers these five areas for

the period until 2013. In Rotterdam, selected

streets in the Delfshaven borough were sub-

sequently added in 2014. Outside Rotterdam,

Capelle aan den IJssel, part of the Rotterdam

region, and the city of Nijmegen requested

and received permission to implement the

Act in 2015, followed by Vlaardingen – also

part of the Rotterdam region – in 2016.

4

Results

Excluded residents

As mentioned, the Act allows for the exclu-

sion of residents by socio-economic status

and duration of residency. Based on these

criteria, and on the status of other house-

hold members, we have been able to identify

around 20,000 adult individuals in the

Rotterdam region for each year who would

have been excluded by the Act (to compare,

a total of 957,846 adults were living in the

region in 2013). Table 1 shows the character-

istics of this group. From 2004 to 2008 we

see a steady drop in the number of excluded

residents in the region. After the 2008 eco-

nomic crisis, their number rises again and

stabilises in 2012 and 2013 to nearly 19,000

individuals. Excluded residents predomi-

nantly live in the Rotterdam municipality

rather than in the surrounding region.

Compared with the reference group,

excluded residents are younger, and are

more often male and living in single-person

households. They are also more likely to be

first or second generation immigrants. More

recent years have seen an increase in labour

immigrants from Central and Eastern

Europe, a group viewed as problematic by

several local politicians and officials.

Newly arrived excluded residents have less

personal income than the reference group.

Yet this difference vanishes within five years.

This implies that excluded residents show

considerable social mobility, particularly

young individuals (data not shown), though

on average they retain a low income. Lastly,

the group has a dynamic composition; every

year about half of the group is no longer

categorised as excluded. Between 2008 and

2013, 27% of the excluded residents moved

out of the region, 22% had found employ-

ment, 31% had achieved sufficient years of

residency, and 4% had both found employ-

ment and had sufficient years of residency.

Housing market position of excluded

residents

A requirement for the Act’s designation is

that it should not constrain excluded

van Gent et al. 2343

households too much in finding accommoda-

tion elsewhere within the region. In other

words, it should not impede the housing mar-

ket position of excluded residents. Figure 2

shows that annual residential mobility rates

are high among the excluded group, and have

in fact increased since the Act was implemen-

ted in 2006: from 34% in 2004 to 38% in

2013. It must, however, be borne in mind that

the total group of excluded residents also

includes those who have newly moved to the

region in the preceding year, meaning that a

share of the group has moved by definition.

In 2004, 18.7% of excluded residents (3931 of

21,060 residents) had moved to the region in

that same year; by 2013, their share had

increased to 24.6% (4578 of 18,644). When

looking at excluded households who have

livedintheRotterdamregionforatleastone

year, mobility rates are relatively high but

remain fairly stable over time at around

19%. These trends suggest that the Act has

not had a considerable impact on the residen-

tial moving opportunities of the targeted pop-

ulation, nor has it led to a more r estricted

influx of unemployed residents moving in

from outside the region. The relatively high

mobility rates can at least partially be

explained by the fact that excluded residents

are often relatively young adults in small

households. This group typically tends to

move house more often, because of life

course events in early age. It may also indi-

cate that excluded residents struggle to access

Table 1. Characteristics of excluded residents in Rotterdam region, 2004 and 2013. Distributions in %.

Excluded residents Reference group

2004 2013 2004 2013

Total N 21,060 18,644 81,632 70,720

Location Rotterdam 76.1 73.3 68.0 64.9

Surrounding region 23.9 26.7 32.0 35.1

Age 16–24 19.9 14.1 4.9 4.3

25–34 36.0 35.6 18.3 15.3

35–54 34.8 40.0 46.8 50.8

55–64 7.5 9.4 27.8 28.2

65 + 1.8 0.9 2.2 1.4

Gender Male 52.9 54.0 44.9 44.9

Female 47.1 46.0 55.1 55.1

Ethnicity Native Dutch 17.1 19.1 47.6 40.9

Non-Western non-native 65.2 54.1 42.6 49.6

Western non-native 17.8 26.8 9.8 9.5

Household composition Single person 56.7 63.5 38.0 46.6

Multi-person no children 9.8 8.6 19.3 12.3

Multi-person with children 14.5 11.5 22.6 18.5

Single parent 18.2 15.7 19.4 21.9

Other 0.9 0.7 0.7 0.7

Duration of residency in

Rotterdam urban region

\ 1 year 18.7 24.6 0 0

1\2 years 18.7 19.2 0 0

2\3 years 18.0 16.1 0 0

3\4 years 16.9 15.0 0 0

4\5 years 14.6 13.8 0 0

5\6 years 13.2 11.3 0 0

.6 years 0 0 100 100

Source: Authors’ calculation based on SSD data (Statistics Netherlands).

2344 Urban Studies 55(11)

secure housing and instead have to settle for

more temporary and precarious housing

arrangements, leading to the formation of

chaotic and capricious housing pathways

(Hochstenbach and Boterman, 2015).

While mobility rates are largely unaf-

fected by the Act, there are notable shifts

with regards to where excluded residents

move to (see Table 2). Of all excluded resi-

dents that moved to or within the region in

2004, 79.7% moved to or within the

Rotterdam municipality. In the year following

the Act’s implementation this share did some-

what decrease, but with 73.4% in 2013,

Rotterdam remains the most important desti-

nation. Since around 63% of all movers set-

tles in Rotterdam, excluded residents remain

overrepresented here. During the 2004–2013

period, only Schiedam, which borders

Rotterdam, stands out as a new destination

for excluded residents: in 2004, 5.2% of all

excluded residents settled in Schiedam, and

this increased to 8% in 2013. The eastern part

of Schiedam in particular has many afford-

able private-rental dwellings providing easy

access.

The most notable spatial shifts take place

within Rotterdam. Figure 3 compares the

influx of excluded residents in 2004/2005

with 2012/2013 by mapping the percentage

point change between these two time peri-

ods. The map confirms that the Act has led

to a substantial decrease in the influx of tar-

geted individuals into the designated neigh-

bourhoods. Carnisse is the exception with a

0 to 1 percentage point increase, partly

because the area was already subject to an

experiment that was the predecessor of the

Act. Decreasing shares can also be seen in

the city’s central neighbourhoods, as these

are subject to processes of gentrification

(Hochstenbach and Van Gent, 2015).

Figure 2. Residential mobility rates (% moved of group, during the previous year) of different population

groups, compared over time 2004–2013.

Note: ‘Excluded residents (all)’ includes residents who have newly moved into the region and who have therefore by

definition moved. ‘Excluded residents (duration of residence .1 yr)’ only looks at the residential mobility rates of those

who have lived in the Rotterdam region for at least one year.

Source: Authors’ calculation based on SSD data (Statistics Netherlands).

van Gent et al. 2345

Figure 3 reveals three ‘clusters’ where the

influx of excluded residents has notably

increased. First, there are several low-status

neighbourhoods adjacent or close to the des-

ignated neighbourhoods. These are charac-

terised by high shares of low-income

households and large shares of low-quality

private-rental dwellings. Nearby neighbour-

hoods where there was a decrease in

excluded residents have generally been sub-

ject to intensive urban renewal processes and

changes in the housing stock. Second, a clus-

ter of relatively poor neighbourhoods with a

large cheap private-rental stock exists in the

west of the city. A third cluster is located in

the east of the city, where post-war housing

estates and low-rise family dwellings domi-

nate. Shares of low-income and unemployed

residents are generally low here, yet the age-

ing housing stock has meant a process of

relative downgrading. To be sure, several

northern neighbourhoods also saw an

increase in excluded residents, but these

high-status areas continue to have a substan-

tial underrepresentation of low-income

households.

In sum, the Act has had notable effects

on the housing market position of excluded

residents. Residential mobility does not seem

to be affected, but the geography of such

mobility is. By curtailing the influx of resi-

dents in the designated areas, the Act has

redirected a share of low-income households

to other neighbourhoods that are either

similarly low-status or subject to socio-

economic downgrading. Excluded residents

are faced with structurally decreasing

options. This is due to the Act, but may also

be attributed to regular housing policies.

Renewal and tenure conversions led to a

decrease of 16,574 rental dwellings in

Rotterdam’s housing stock between 2006

and 2014. The Act excludes targeted resi-

dents from an additional 20,108 rental units

in the designated neighbourhoods. For

excluded residents, this amounts to a total

decrease in accessible units from 208,531 in

2006 to 171,849 in 2014 (218%). Our analy-

ses indicate that for many excluded resi-

dents, an important coping strategy to deal

with their precarious housing position is to

share a dwelling with multiple households.

5

Change in social composition in designated

areas

The Act has proven to be effective in chang-

ing the mobility behaviour of recently

Table 2. Moving destinations (municipalities in the Rotterdam region) of excluded residents in 2004 and

2013, compared with all moved residents. Presented data include moves within and from outside region.

Municipality Moved excluded residents All moved residents

2004 (%) 2013 (%) 2004 (%) 2013 (%)

Rotterdam 79.7 73.4 62.2 63.6

Schiedam 5.2 8.0 6.3 6.1

Vlaardingen 4.1 4.0 5.2 5.0

Capelle aan den IJssel 3.0 4.0 4.7 4.2

Other

a

8.0 10.6 21.7 21.1

Total % 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0

Total N 7258 7087 98,708 92,491

Note:

a

Albrandswaard, Barendrecht, Bernisse, Brielle, Hellevoetsluis, Krimpen aan den IJssel, Lansingerland, Maassluis,

Ridderkerk, Spijkenisse, and Westvoorne.

Source: Authors’ calculation based on SSD data (Statistics Netherlands).

2346 Urban Studies 55(11)

arrived low-income residents. The question

is whether this has led to substantial changes

in the designated areas’ social composition.

It may be that other unemployed residents –

the reference group – replace excluded resi-

dents, as often predicted by local officials.

Between 2004 and 2013, however, the refer-

ence group also decreased in size in the des-

ignated neighbourhoods (Table 3). In other

words, the reduced influx of excluded resi-

dents was not substituted by an increased

influx of other unemployed residents. This is

also the case when looking at the composi-

tion of in-movers. Instead, the share of

working residents increased at an above-

average rate in the designated neighbour-

hoods. The increase in low-income employed

residents is mostly the consequence of

residential moves, as the former have come

to replace excluded residents among in-

movers. The increase in employed house-

holds with a middle or higher income can be

attributed to in situ upward social mobility

and decreasing moves out of these neigh-

bourhoods.

6

Since the implementation of the

Act, the proportion of employed residents

has thus increased at an above-average rate

in the designated areas, at the cost of differ-

ent groups of unemployed residents in

general.

Conditions of the living environment in

designated areas

According to the theory of change underpin-

ning the Act, a change in population

Figure 3. Change in excluded residents moving into or within a neighbourhood (percentage point change

between 2004/2005 and 2012/2013) (OC: Oud-Charlois, C: Carnisse, T: Tarwewijk, B: Bloemhof, H:

Hillesluis).

Source: Authors’ calculation based on SSD data (Statistics Netherlands).

van Gent et al. 2347

composition should have direct and indirect

effects on the social and physical conditions of

the designated neighbourhoods. A longitudinal

analysis of the (modified) Safety Index illumi-

nates how safety figures and perceptions chan-

ged over time from 2001 to 2013 in the

designated neighbourhoods and in the city

overall (Table 4). The index scores are meant

to be comparable over time or across spatial

units. Prior to the Act’s implementation,

between 2001 and 2006, safety scores improved

in all designated neighbourhoods in line with

citywide improvements. Between 2006 and

2013 – during which time the Act was in place

– safety scores declined in all designated neigh-

bourhoods, while the citywide score more or

less stabilised. Further analyses of the various

dimensions of the index show similar relatively

negative trends. The designated neighbour-

hoods show particularly negative developments

for ‘cleanliness and repair’, ‘nuisance’, and

‘traffic’ – the dimensions that come closest to

capturing the concept of liveability (data not

shown).

Our ecological analyses confirm these

trends (Table 5). We conducted linear regres-

sion models with the change in the relative

Safety Index for the 2006–2013 period. These

models control for various neighbourhood

characteristics and other housing market

interventions such as demolitions, new-build

developments and tenure conversions. These

Table 3. Socio-economic population composition in designated neighbourhoods and Rotterdam (2004 and

2013) in, and percentage point change.

Year Excluded Reference Working

low

Working

mid/high

Other Total

(%)

Total

N

Designated neighbourhoods 2004 6.8 16.7 14.6 41.3 20.6 100 44,877

2013 4.7 13.1 16.8 44.1 21.3 100 44,615

Change 2 2.1 23.6 2.2 2.8 0.7 0 2262

Rotterdam 2004 3.7 13.1 9.7 46.8 26.7 100 423,735

2013 3.1 10.9 10.2 48.4 27.4 100 420,984

Change 2 0.6 22.2 0.5 1.6 0.7 0 22751

Note: ‘Working low’ is defined as having a household income lower than e34,085 gross per year (corrected for inflation).

This is the threshold for social housing eligibility. The group ‘Other’ consists mostly of pensioners and students.

Source: Authors’ calculation based on SSD data (Statistics Netherlands).

Table 4. Modified safety index score per year in the designated neighbourhoods.

2001 2003 2005 2006 2007 2009 2011 2013

Bloemhof 4.5 4.8 5.2 6.4 5.9 5.7 5.1 5.4

Carnisse 5.6 6.6 6.6 7.0 6.4 6.7 6.6 6.4

Hillesluis 4.3 4.4 6.4 6.8 5.5 5.2 5.6 4.8

Oud-Charlois 5.5 5.4 5.3 6.2 6.8 7.2 7.3 6.0

Tarwewijk 4.2 4.3 5.5 6.6 5.5 4.8 6.6 5.4

Total designated

a

4.8 5.1 5.7 6.6 6.0 5.9 6.2 5.6

Rotterdam 5.8 6.5 7.3 7.7 7.8 7.8 8.1 7.6

Note:

a

Average of the five neighbourhoods, weighted according to total population size.

Source: Authors’ calculation based on Safety Index data (Dienst Veiligheid).

2348 Urban Studies 55(11)

analyses indicate that the designated neigh-

bourhoods have performed significantly

worse on the Safety Index than other neigh-

bourhoods in the city. Additional analyses

for various sub-periods confirm these find-

ings. Although it is impossible to assert how

these neighbourhoods would have fared if

the Act had not been implemented, these

findings do not provide any evidence that

the Act, or any other measures specifically

targeting these areas, have been successful.

Discussion and conclusion

Our evaluation sought to gauge the socio-

spatial effects of the controversial Act on

Extraordinary Measures for Urban Problems

in the Netherlands, particularly its exclusion-

ary provisions designed to support local poli-

cies and improve local social conditions. As

such, the Act affects excluded individuals as

well as designated neighbourhoods. First, the

Act is effective in excluding residents who

have no income from work, pensions or stu-

dent benefits and an insufficient length of

residency in the region. As a consequence,

this group of low-income residents – often

young, male, single, and non-native – is

forced to find residence in other areas with

accessible and affordable housing. These are

often private and affordable rental dwellings

located in relatively deprived urban neigh-

bourhoods and in the downgrading post-war

periphery. Together with changes in housing

market structure – notably the sale and

demolition of affordable rental dwellings –

the Act contributes to a worsening housing

market position of excluded residents. With

regard to spatial effects, the five designated

areas show a slow shift in social composition

as a result of residential mobility and in situ

social mobility. The share of excluded resi-

dents is decreasing, as is the share of the ref-

erence group, while more people in

employment are moving in. Also, while this

evaluation is unable to pinpoint the exact

causality, the state of the living environment

in the designated areas seems to be worsening

rather than improving. Given the Act’s objec-

tives and extraordinary means, the lack of

Table 5. Neighbourhood-level linear regression models (N = 58), dependent variable: change in modified

Safety Index 2006–2013.

Model 0 Model 1 Model 2

B Beta B Beta B Beta

Independent variables

(Constant) 0.207 0.251 21.090 *

Designated neighbourhood (dummy) 21.095 20.321* 21.125 20.330** 21.316 20.386**

Percentage demolished dwellings

2004–2011

20.061 20.389* 20.034 20.221

Percentage new-build dwellings

2004–2011

0.033 0.252 20.008 20.064

Absolute change real estate values

(*e1000)

0.017 0.274

Percentage point change share

homeownership

0.030 0.166

Residential turnover rate (average

2004 and 2013)

0.075 0.333**

Note: *p \ 0.05; **p \ 0.01. Only neighbourhoods with a minimum of 500 residents have been included.

Source: Authors’ calculation based on SSD data (Statistics Netherlands), and data provided by OBI Rotterdam and Dienst

Veiligheid.

van Gent et al. 2349

results is remarkable, but not unprecedented

in urban policy evaluations (see Lawless and

Pearson, 2012; Permentier et al., 2013).

This paper has evaluated a new iteration

of urban policy and social mixing; one that

banks on exclusion rather than targeted

physical interventions to mix and integrate

populations in urban marginality. Our find-

ings show that the Act on Extraordinary

Measures for Urban Problems has had

effects on residential mobility flows and

population mix, but has had little effect on

living conditions. There may be various rea-

sons for the lack of effects on living condi-

tions. One reason may be that the policy

simply does not work at all. Given the com-

plete absence of positive indications, this is a

very plausible explanation for our findings.

Another reason may be that the policy has

had positive effects, but that its impact has

been outweighed by other developments

pushing in a different direction. The discon-

tinuation of renewal funds and other budget

cuts may help to explain why we find that –

grosso modo – liveability and safety have

decreased at an above-average rate in the

designated areas since implementation of the

Act. Whatever the explanation, it is clear

that the Act has not provided an extra boost

to vulnerable neighbourhoods, as it officially

aims to do. It has, however, had an effect on

the social composition of the designated

neighbourhoods. Apart from the more fun-

damental issue that the Act suspends the

rights of specific groups of people, this find-

ing suggests that the mobility and choices of

unemployed residents have been restricted.

We consider this both a cost and a sacrifice.

However, this is not how the government

has interpreted the results. In an official

response to the findings presented in this

paper, the Minister of Housing stated that it

is inherently difficult to pinpoint causality,

but that the changes in the social composi-

tion in the designated areas do confirm that

the policy is on the right track (Ministry of

the Interior and Kingdom Relations, 2015).

This response dovetails with local adminis-

trators who argue that the Rotterdam Act

serves them well.

The implementation of the Act may seem

to be small-scale, but it has a self-propelling

and expansive tendency. Administrators of

some areas that have captured the migration

flows of excluded residents have proceeded

to use the Act to close off neighbourhoods

in their jurisdictions (see Uitermark et al.,

2017). The Act was also expanded in 2016 to

not only improve living conditions but also

target public safety more directly. It now

holds provisions to allow the exclusion of

residents based on police records of crime,

‘anti-social behaviour’, and suspicions of

extremism and radicalism.

7

These policy

changes represent a further step towards a

reliance on profiling and exclusion.

The exclusionary design of the Act may

also travel across borders. The Dutch case is

unique in terms of scope and legal frame-

work, although a few similar initiatives have

been deployed elsewhere. Yet, the Act may

foreshadow a shift in European policy mak-

ing, as it may be understood as part of a

broader trend towards ‘lean and mean’ sta-

tecraft (see Peck, 2012). Such governance is

lean in the sense that it is agile, targeted, ver-

satile, selective and affordable. This does not

necessarily imply that these policies are cost-

effective – as the lack of real results in

improving social conditions in our case sug-

gests – but they do not require large-scale

and long-term investments. Interestingly, the

interviews we conducted reveal that most

local practitioners are content with the Act,

but also lament the lack of funds to restruc-

ture and renew the areas wholesale; they

embrace the Act as a second-best option.

So, policies such as the Act may serve as a

comparatively affordable stand-in for more

conventional social mixing initiatives.

Recognising that the Act is not a panacea,

the Rotterdam government and central

2350 Urban Studies 55(11)

government have stepped up efforts to

improve coordination among professionals

in the neighbourhoods of Rotterdam

South (the so-called National Program for

Rotterdam South). The ideal of the mixed

and integrated neighbourhood therefore

appears to live on as it does in other

European countries (Uitermark, 2014), but

current policies working towards the realisa-

tion of this ideal have to make do with much

less funding than during the heyday of urban

restructuring policy.

Second, policies may be mean in the sense

that they locate the cause for social problems

in groups suffering from stigmatisation and

deprivation. Yet from a perspective of social

costs and benefits, our findings raise serious

questions about whether the costs of impair-

ing freedom of movement for a specific

socio-economic group add up to any social

improvement. While the criteria for excluding

residents seem clear-cut, our analyses show that

a wide net is cast. A dynamic and diverse group

of low-income residents is targeted, with the

implicit assumption that these individuals are a

burden. At the expense of the rights and entitle-

ments of this group, the government expands

its discretion by increasing its possibilities to

exercise power in the form of enclosure and

exclusion. The Act originates in right wing poli-

tics that promote strong-arm tactics with the

promise of ‘getting things done’ and reasserting

control over the city (Schinkel and Van den

Berg, 2011; Uitermark and Duyvendak, 2008;

cf. Dikecx, 2007; Smith, 1996), but its adoption

and expansions were supported by a wide spec-

trum of political parties who were all sensitive

to the underlying sentiment that you cannot

make an omelette without breaking an egg.

Our results demonstrate that breaking an egg

does not necessarily make an omelette.

Acknowledgement

The empirical sections draw on a policy evalua-

tion, which was commissioned by the Ministry

of the Interior and Kingdom Relations. The

evaluation report was published as Hochstenbach

et al. 2015. The authors would like to thank the

members of the advisory committee for their com-

ments and suggestions on the report. The analysis

presented here is the sole responsibility of the

authors and does not necessarily reflect the posi-

tion or opinions of the advisory committee, the

Ministry, the Parliament, or the Government.

This paper presents results based on the calcula-

tions by the authors using non-public microdata

from the System of Social Statistical Datasets of

Statistics Netherlands.

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of

interest with respect to the research, authorship,

and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The aforementioned evaluation report was com-

missioned and funded by the Ministry of the

Interior and Kingdom Relations following a

request for an independent evaluation by mem-

bers of the Dutch Parliament. Justus Uitermark

acknowledges the financial support of a VENI-

grant from NWO, the Netherlands Organization

for Scientific Research (#451-12-035).

Notes

1. The Act is best known for these exclusionary

provisions (chapter 3, article 8), though it

also offers municipalities the possibility to

give households priority access to designated

areas based on socio-economic criteria (chap-

ter 3, article 9). This provision has not been

implemented in Rotterdam, and was first

used in Capelle aan de IJssel in 2015 and in

Vlaardingen in 2016.

2. The Hope VI grant programme in the USA is

comparable in its social mixing approach, but

lacks an integrated social programme.

3. All policy quotes are translated from Dutch

by the authors.

4. Nijmegen is only implementing the exclusion-

ary provisions discussed in this paper (chapter

3, article 8) and Vlaardingen only the priority

provisions (article 9). Capelle aan de IJssel is

implementing both provisions.

van Gent et al. 2351

5. Sharing a dwelling, as well as moving in with

someone, also serves as a way for excluded res-

idents to be able to access housing in the desig-

nated areas, since only new tenants have to

fulfill the housing permit criteria, while addi-

tional household members do not. Since 2014,

stricter regulations regarding household forma-

tion have been in place, making it more diffi-

cult for excluded residents to move in with

someone living in a designated neighbourhood.

6. This is an effect of the economic crisis: declin-

ing housing values and sales figures have led

to reduced residential mobility rates, particu-

larly among higher-income homeowners.

7. At the time of writing, the Leefbaar

Rotterdam alderman responsible has purpose-

fully expressed his intention to make use of

these new provisions as soon as possible. This

is unsurprising given that the expansion essen-

tially legalises and regulates a practice that

many municipalities, including Rotterdam,

had already adopted, but without oversight.

References

Andersson R and Musterd S (2005) Area-based

policies: A critical appraisal. Tijdschrift voor

Economische en Sociale Geografie 96(4):

377–389.

Baeten G (2016) The production of housing

inequality. Keynote in: Housing Wealth and

Welfare conference, Amsterdam, Netherlands,

26 May 2016.

Bergsten Z and Holmqvist E (2013) Possibilities

of building a mixed city – Evidence from

Swedish cities. International Journal of Hous-

ing Policy 13(3): 288–311.

Bonfigli F (2013) Security policies in a multicul-

tural area of Milan: Power and resistance. In:

Duxbury N, Canto Moniz G and Sgueo G

(eds) Rethinking Urban Inclusion. Coimbra:

Centre for Social Studies, pp. 374–389.

Bricocoli M and Cucca R (2016) Social mix and

housing policy: Local effects of a misleading

rhetoric. The case of Milan. Urban Studies

53(1): 77–91.

De Wilde M and Franssen T (2016) The material

practices of quantification: Measuring ‘depri-

vation’ in the Amsterdam neighborhood pol-

icy. Critical Social Policy 36(4): 489–510.

Dikecx M (2007) Badlands of the Republic: Space,

Politics, and Urban Policy. Oxford: Blackwell.

Finn D, Atkinson R and Crawford A (2007) The

wicked problems of British cities: How New

Labour sought to develop a new integrated

approach. In: Donzelot J (ed.) Ville, City, Vio-

lence and Social Dependency. Paris: CEDOV,

pp. 25–75.

Fridberg T and Lausten M (2004) Fleksibel

udlejning af almene familieboliger. Copenha-

gen: Erhvervs- og Boligstyrelsen.

Galster G (2007) Should policy makers strive for

neighborhood social mix? An analysis of the

Western European evidence base. Housing

studies 22(4): 523–545.

Hochstenbach C and Boterman WR (2015) Navi-

gating the field of housing: Housing pathways of

young people in Amsterdam. Journal of Housing

and the Built Environment 30(2): 257–274.

Hochstenbach C and Van Gent WPC (2015) An

anatomy of gentrification processes: Variegat-

ing causes of neighbourhood change. Environ-

ment and Planning A 47(7): 1480–1501.

Hochstenbach C, Uitermark J and Van Gent W

(2015) Evaluatie effecten Wet bijzondere maa-

tregelen grootstedelijke problematiek (‘Rotter-

damwet’) in Rotterdam. Amsterdam: AISSR

Universiteit van Amsterdam.

Kaal H (2011) A conceptual history of livability:

Dutch scientists, politicians, policy makers and

citizens and the quest for a livable city. City

15(5): 532–547.

Lawless P and Pearson S (2012) Outcomes from

community engagement in urban regeneration:

Evidence from England’s New Deal for Com-

munities Programme. Planning Theory and

Practice 13(4): 509–527.

Miltenburg E (2017) A different place to different

people; Conditional neighbourhood effects on

residents’ socio-economic status. PhD thesis.

Amsterdam: Universiteit van Amsterdam.

Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations

(2014) Besluit nieuwe aanvraag en aanvraag om

verlenging toepassing Wbmgp in door de

gemeenteraad voorgelegde gebieden. 14 april

2014. Den Haag: Ministerie van Binnenlandse

Zaken en Koninkrijksrelaties.

Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations

(2015) Kabinetsreactie op rapport wetenschap-

pelijke evaluatie van de Wet bijzondere

2352 Urban Studies 55(11)

maatregelen grootstedelijke problematiek

(kenmerk 2015-0000656625). Den Haag:

Ministerie van Binnenlandse Zaken en

Koninkrijksrelaties.

Musterd S and Ostendorf W (2008) Integrated

urban renewal in The Netherlands: A critical

appraisal. Urban Research & Practice 1(1):

78–92.

Noordegraaf M (2008) Meanings of measure-

ment: The real story behind the Rotterdam

Safety Index. Public Management Review

10(2): 221–239.

Ouwehand A and Doff W (2013) Who is afraid of

a changing population? Reflections on housing

policy in Rotterdam. Geography Research

Forum 33(1): 111–146.

Parkinson M (1998) Combating Social Exclusion:

Lessons From Area-Based Programmes in Eur-

ope. Bristol: Policy Press.

Peck J (2012). Austerity urbanism: American cit-

ies under extreme economy. City 16(6):

626–655.

Permentier M, Kullberg J and Van Noije L (2013)

Werk aan de wijk. Een quasi-experimentele eva-

luatie van het krachtwijkenbeleid. Den Haag:

Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau.

Sampson RJ (2012) Great American City: Chi-

cago and the Enduring Neighborhood Effect.

Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Sarkissian W (1976) The idea of social mix in

town planning: An historical review. Urban

Studies 13(3): 231–246.

Schinkel W and Van den Berg M (2011) City of

exception: The Dutch revanchist city and the

urban homo sacer. Antipode 43(5): 1911–1938.

Skifter Andersen H (2003) Urban Sores; On the

Interaction Between Segregation, Urban Decay

and Deprived Neighborhoods. Aldershot:

Ashgate.

Slater T (2013) Your life chances affect where

you live: A critique of the ‘cottage industry’ of

neighbourhood effects research. International

Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37(2):

367–387.

Smith N (1996) The New Urban Frontier: Gentri-

fication and the Revanchist City. London:

Routledge.

Stone CN and Stoker RP (2015) Urban Neighbor-

hoods in a New Era; Revitalization Politics in

the Postindustrial City. Chicago, IL: Univer-

sity of Chicago Press.

Tweede Kamer (2005) Memorie van Toelichting.

(Regels die een geconcentreerde aanpak van

grootstedelijke problemen mogelijk maken (Wet

bijzondere maatregelen grootstedelijke problema-

tiek)).Vergaderjaar 2004-2005, 30 091, nr.3. The

Hague: Tweede Kamer der Staten-Generaal.

Uitermark J (2003) ‘Social mixing’ and the man-

agement of disadvantaged neighbourhoods:

The Dutch policy of urban restructuring revis-

ited. Urban Studies 40(3): 531–549.

Uitermark J (2014) Integration and control: The

governing of urban marginality in Western

Europe. International Journal of Urban and

Regional Research 38(4): 1418–1436.

Uitermark J and Duyvendak JW (2008) Civilizing

the city: Populism and revanchist urbanism in

Rotterdam. Urban Studies 45(7): 1485–1503.

Uitermark J, Hochstenbach C and Van Gent W

(2017) The statistical politics of exceptional

territories. Political Geography 57: 60–70.

Van Gent WPC (2010) Housing context and

social transformation strategies in neighbour-

hood regeneration in Western European cities.

International Journal of Housing Policy 10(1):

63–87.

Van Gent WPC, Musterd S and Ostendorf W

(2009) Disentangling neighborhood problems;

Area-based interventions in Western European

cities. Urban Research & Practice 2(1): 53–67.

Wacquant L (2008)

Urban Outcasts: A Compara-

tive Sociology of Advanced Marginality.Cam-

bridge: Polity.

Walter RJ, Viglione J and Skubak Tillyer M

(2017) One strike to second chances: Using

criminal backgrounds in admission decisions

for assisted housing. Housing Policy Debate

27(5): 734–750.

van Gent et al. 2353